Abstract

Capsid assembly among the herpes-group viruses is coordinated by two related scaffolding proteins. In cytomegalovirus (CMV), the main scaffolding constituent is called the assembly protein precursor (pAP). Like its homologs in other herpesviruses, pAP is modified by proteolytic cleavage and phosphorylation. Cleavage is essential for capsid maturation and production of infectious virus, but the role of phosphorylation is undetermined. As a first step in evaluating the significance of this modification, we have identified the specific sites of phosphorylation in the simian CMV pAP. Two were established previously to be adjacent serines (Ser156 and Ser157) in a casein kinase II consensus sequence. The remaining two, identified here as Thr231 and Ser235, are within consensus sequences for glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) and mitogen-activated protein kinase, respectively. Consistent with Thr231 being a GSK-3 substrate, its phosphorylation required a downstream “priming” phosphate (i.e., Ser235) and was reduced by a GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Phosphorylation of Ser235 converts pAP to an electrophoretically slower-mobility isoform, pAP*; subsequent phosphorylation of pAP* at Thr231 converts pAP* to a still-slower isoform, pAP**. The mobility shift to pAP* was mimicked by substituting an acidic amino acid for either Thr231 or Ser235, but the shift to pAP** required that both positions be phosphorylated. Glu did not substitute for pSer235 in promoting phosphorylation of Thr231. We suggest that phosphorylation of Thr231 and Ser235 causes charge-driven conformational changes in pAP, and we demonstrate that preventing these modifications alters interactions of pAP with itself and with major capsid protein, suggesting a functional significance.

Formation of herpes virions begins with the assembly of procapsids in the nucleus of infected cells (17, 47, 54). Organization and maturation of these particles requires the involvement of an abundant protein, called the assembly protein precursor (pAP) in cytomegalovirus (CMV) (6, 17, 56, 57). pAP and its genetically related maturational protease have key roles in both early and late steps of the assembly process. One of the first is translocating the major capsid protein (MCP) into the nucleus, which is initiated by self-interaction of pAP through its amino-conserved domain (5, 40, 61). This self-interaction potentiates or stabilizes the interaction of pAP, through its carboxyl-conserved domain, with MCP (2, 24, 40, 61). By forming a complex with MCP, pAP provides the nuclear localization sequences that MCP lacks, enabling the complex to enter the nucleus (42). Within the nucleus, pAP further associates with itself and with the protease precursor to form an internal scaffolding structure that helps organize MCP into the procapsid shell. Ultimately, in preparation for packaging viral DNA into the nascent capsid, pAP is cleaved by the protease (33, 45, 60) and eliminated from the capsid cavity. In addition to this cleavage, pAP and its homologs in other herpesviruses are phosphorylated (14, 16, 20, 26).

These various changes in pAP and its interactions provide potential points of control through which the assembly process may be regulated. Although pAP cleavage is essential for the production of infectious virus (8, 15, 44), the nature and significance of pAP phosphorylation is unknown. Efforts to learn more about the importance of this modification during virus assembly have initially focused on identifying the specific sites phosphorylated. Based on that information, genetic and biochemical studies can be done to determine its functional role. Earlier work established that pAP of simian CMV (SCMV) is phosphorylated on two adjacent serines in a casein kinase II (CKII) consensus sequence (43). Neither of these modifications was essential for pAP interactions that were tested: nuclear translocation, susceptability to cleavage by the maturational protease, and self-interaction. The same study provided evidence for two additional sites whose phosphorylation correlated with electrophoretic mobility shifts during sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). These non-CKII sites were referred to as secondary phosphorylation sites, and the resulting electrophoretic mobility isoforms were designated pAP* and pAP** (43).

In the work reported here, we have used site-directed mutagenesis, peptide mapping, and mass spectrometry to identify these two secondary sites and show that their phosphorylation is responsible for slowing the electrophoretic mobility of pAP. The sites lie within consensus phosphorylation sequences for glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase. We suggest that their phosphorylation alters pAP conformation, and we provide evidence that this modification affects pAP interactions with itself and with the MCP.

(Initial reports of this work were presented at the XVIII Phage/Virus Assembly meeting, Woods Hole, Mass., June 2003; the 22nd meeting of the American Society for Virology, Davis, Calif., July 2003; and the 28th International Herpesvirus Workshop, Madison, Wis., July 2003.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human foreskin fibroblasts and human embryonic kidney cells (cell line 293; ATCC CRL-1573) were grown in Dulbecco's high-glucose modified Eagle's medium containing antibiotics and 10% fetal calf serum (16). Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9, CRL-1711; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) insect cells were propagated in spinner flasks (catalogue no. F7987; Techne, Burlington, N.J.) containing Grace's insect medium with antibiotics and 10% fetal calf serum (23); infections with recombinant baculoviruses (rBV) were done in stationary cultures. SCMV strain Colburn (16) was used to infect ≈107 human foreskin fibroblast cells for the purpose of preparing 32P-labeled, infected-cell assembly protein. Radiolabeling was for 3 days in complete medium containing 400 μCi of 32Pi (ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.) per milliliter. B-capsids were recovered from the cells by rate-velocity centrifugation, as described previously (16, 31), but with phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1 μM okadaic acid, and 5 μM cyclosporine A) (9, 30) included in the NP-40 cell disruption solution.

To produce 32P-labeled CKII− pAP for sequence analysis, ≈7 × 106 Sf9 cells in a 10-cm petri dish were infected at a multiplicity of infection of ≈5 with rBV KC34 (which encodes the CKII− pAP mutation) (43) and maintained at 28°C. Radiolabeling was carried out for 3 days in Grace's medium containing 100 μCi of 32Pi (ICN) per ml added 1 day after infection.

Plasmids and cloning.

Standard techniques were used to clone and propagate plasmids (1, 49). Phosphorylation site mutants were made from either AW1 (the coding sequence for SCMV strain Colburn pAP in RSV.5neo) (60) or SP22 (the coding sequence for the CKII− mutation of pAP in RSV.5neo) (43). Alanine was introduced as a conservative change for Thr and Ser; glutamic acid was introduced as a conservative change for pThr and pSer. Mutations were made by using annealed mutagenic oligonucleotides, 52 bp in length, and terminating with NheI-compatible ends. The oligonucleotides also contained a silent mutation, an AgeI restriction site (italicized in the following sequences), that allowed detection of the oligonucleotide. The annealed mutagenic oligonucleotides were ligated into NheI-cleaved, gel-purified AW1 or SP22. DNA sequencing analysis verified the constructs. In the sequences that follow, the mutagenic portion of the oligomer with changes from the wild type is underlined, and the name of the mutation and its laboratory designation (in parentheses) are supplied: 5′-CTAGCGGCACCGGTGGCT-3′ produced T231A (RC7); 5′-CTAGCGGAACCGGTGGCTTCT-3′ produced T231E (RC5); 5′-CTAGCGACACCGGTGGCTGCTCCG-3′ produced S235A (JRB6) and S235A/CKII− (JRB4); 5′-CTAGCGACACCGGTGGCTGAACCGACA-3′ produced S235E (RC4); 5′-CTAGCGACACCGGTGGCTTCTCCGACAACGACCACGGCGCAT-3′ produced S241A/CKII− (JRB5); 5′-CTAGCGGCACCGGTGGCTGCACCGACA-3′ produced T231A/S235A (RC8); 5′-CTAGCGGAACCGGTGGCTGAACCGACA-3′ produced T231E/S235E (RC6); 5′-CTAGCGACACCGGTGGCTGCTCCGACAACGACCACGGCGCAT-3′ produced S235A/S241A/CKII− (JRB8).

For the Saccharomyces cerevisiae two-hybrid assay, phosphorylation mutant genes were subcloned into GAL4 vector pPC86 or pPC97 (3) with PCR primers 5′-GGAAGATCTACATGTCTCACCCTATGAGCGCCGTG-3′ (5′primer) and 5′-TTAGCGGCCGCTTATTCCATTTTATTCAACGCCGC-3′ (3′ primer) to add a BglII and NotI restriction site, respectively. BglII/NotI-digested vector and insert were ligated, and the constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Transfections.

Human embryonic kidney cells in 24-well plates (≈105 cells/well) were transfected with FuGENE (catalogue no. 1814443; Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.) as the enhancer (3:1, FuGENE:DNA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Radiolabeling with 32Pi (400 μCi/ml of growth medium; ICN) was carried out for 3 days, beginning the day after transfection. Transfected cells in one well were harvested directly into 150 μl of immunoprecipitation lysis solution (0.5 M KCl, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 1.0% NP-40 in calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline) or into 70 μl of 4× protein sample buffer (8% SDS, 5.72 M β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 200 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 0.02% bromophenol blue) at 70°C.

Immunoprecipitation, SDS-PAGE, and Western immunoassay.

Immunoprecipitation was done as described previously (59), using a rabbit anti-peptide antiserum to the carboxyl end of pAP (anti-C1) (51). Protease inhibitors (catalogue no. 1836153; Complete Mini, Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors were added to the immunoprecipitation lysis and wash solutions just before use, unless otherwise indicated. In preparation for SDS-PAGE, immunoprecipitation samples were solubilized in 4× protein sample buffer and heated in a boiling-water bath. SDS-PAGE and Western immunoassays (18, 58) with an anti-peptide antiserum to the amino end of pAP (anti-N1) (51) and 125I-labeled protein A (catalogue no. NEX146L; NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) as the secondary reagent were done as described previously. Resolution of the three pAP isomers was improved in longer gels (e.g., 15.5 cm long by 0.75 mm thick) composed of 10% polyacrylamide and by continuing electrophoresis ≈25% longer than required for the bromophenol blue marker dye to reach the end of the gel. Even so, minor contamination between adjacent proteins in peptide comparisons was sometimes noted.

Detection and quantification of radioactivity was by phosphorimaging (Fuji BAS 1000 with Image Quant software, version 2.5; Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), direct autoradiography with Kodak MR film, or fluorography with Kodak Biomax MS film with MS screens, as indicated.

Peptide and amino acid analyses.

Phosphopeptides were prepared and evaluated by two-dimensional (2-D) separations on microcrystalline cellulose thin-layer plates, generally as described previously (19, 43). In summary, the immunoprecipitated 32P-labeled proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the resulting gel was incubated with deionizing resin, dried, and imaged to locate the proteins of interest. The bands were cut from the dried gel, rehydrated in 100 mM NH4HCO3 (≈10 μl/mm2 of dried gel), pulverized, treated for 16 h at room temperature with pronase (≈40 μl/100 μl of gel slurry) (catalogue no. 53702; Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) that had been heated as a solution (1.0 mg/ml of 100 mM NH4HCO3) for 60 min at 37°C, and further processed for analysis on thin-layer plates as described previously (19, 43). The resulting peptides were subjected to electrophoresis at pH 1.9 (1,000 V; 45 min), followed by chromatography (isobutyric acid:butanol:pyridine:acetic acid:water, 65:5:3:2:25) (50). Radiolabeled peptides were detected by phosphorimaging or fluorography.

Phosphoamino acid analyses were done by scraping resolved phosphopeptides from thin-layer plates; eluting them from the cellulose with pH 1.9 electrophoresis buffer and lyophilizing the solution; dissolving the peptides in 6 N HCl and hydrolyzing them at 110°C for 60 min; lyophilizing the solution and dissolving the products in pH 1.9 electrophoresis buffer; adding 5 μg each of pTyr, pThr, and pSer to each sample; subjecting the preparation to the same 2-D separation used for phosphopeptides; and locating the radiolabeled hydrolysis products by fluorography and the phosphoamino acid standards by ninhydrin staining (spraying 0.25% ninhydrin in acetone and developing at 65°C for 15 min). Radioactive ink spots applied to the processed plates enabled the two images to be aligned.

Mass spectrometry.

32P-labeled CKII− pAP, with an amino-terminal His-Trp purification “handle” (52), was expressed from rBV KC34 in Sf9 cells, recovered by Ni2+-immobilized metal affinity chromatography in urea (cell lysis, 8 M; elution, 2 M), concentrated, and further purified by reverse-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) (43). The radiolabeled protein was located among the resulting fractions by scintillation spectrometry using Cerenkov radiation (confirmed by SDS-PAGE), lyophilized, and cleaved 16 h at room temperature with 15 μg of trypsin (catalogue no. 1418025, modified sequencing grade; Roche) in a 100-μl final volume of 100 mM NH4HCO3. The solution was then acidified by adding 3 volumes of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water and subjected to RP-HPLC with a C-18 column (4.6 mm by 25 cm; Vydac, Hesperia, Calif.), with a 1 to 99% gradient of acetonitrile in aqueous 0.1% TFA developed over 75 min. Fractions containing 32P-labeled material were tested by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry to identify the Gln217-Lys267 peptide, combined, lyophilized, and cleaved 16 h at room temperature with 1.0 μg of Endoproteinase GluC (sequencing grade GluC, catalogue no. 1420399; Roche) in a 100-μl final volume of 25 μM NH4HCO3. The solution was acidified by adding 3 volumes of 0.1% TFA in water and subjected to RP-HPLC as above.

The resulting Trp/GluC peptide was then subjected to (i) MALDI-TOF (28, 55) with a Kratos Axima-CFR (Manchester, England) mass spectrometer and (ii) sequence analysis by tandem mass spectrometry (53, 62) with a QSTAR Pulsar quadrupole orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometer (ABI/MDX, Foster City, Calif.), equipped with a Proxeon XYZ manipulator source (Proxeon Biosystems, Odense, Denmark).

Phosphatase treatment (46) of the Gln217-Glu245 peptide was done by first spotting 0.3 μl of fraction 61 (see Fig. 9D) lyophilized and suspended in 5 μl water onto a MALDI plate. An equal volume of calf alkaline phosphatase (catalogue no. 0567744; Roche) diluted 1:10 in water was added to the spotted peptide and incubated for 2.5 min at room temperature. A total of 0.3 μl of water was added, and incubation was continued for another 2.5 min. Matrix material (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, catalogue no. C8982; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) saturated in a 50/50 solution of ethanol/0.1% TFA was added, and the preparation was analyzed by MALDI-TOF.

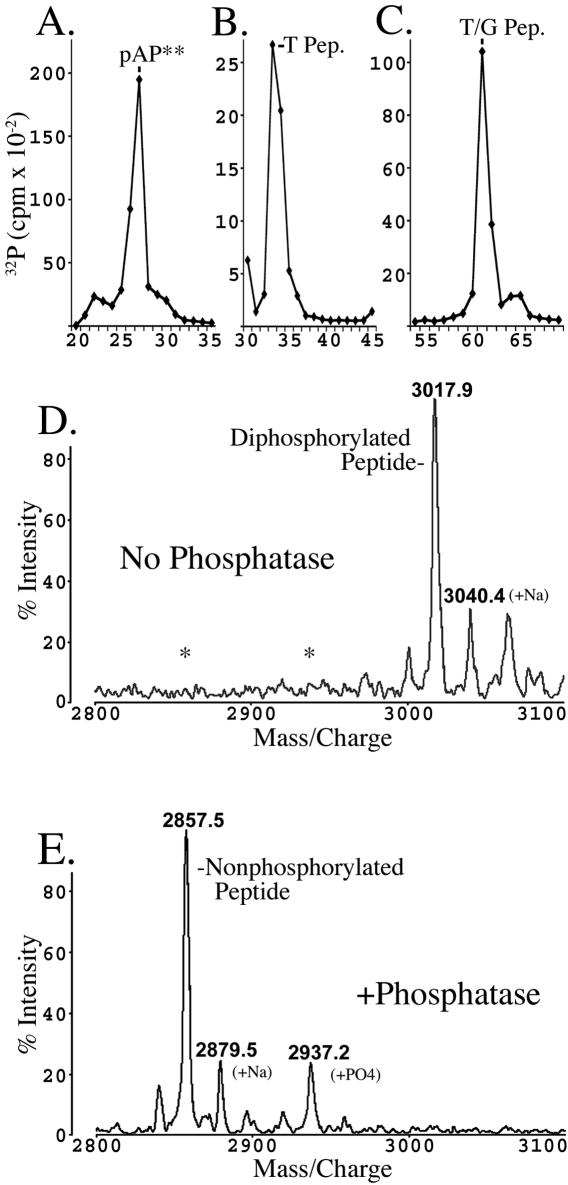

FIG. 9.

Mass spectrometry confirms presence of two phosphates on peptide containing Thr231 and Ser235. The Gln217-Glu245 trypsin/GluC peptide was prepared from 32P-labeled pAP** expressed from rBV KC34, as described in Materials and Methods and Results. The top panels show the radioactivity patterns resulting from RP-HPLC separation of the protein, pAP** (A), the tryptic peptide (T Pep.) (B), and the double-cut trypsin/GluC peptide (T/G Pep.) (C). The resulting peptide was subjected to MALDI-TOF without further treatment (D) or following treatment with calf alkaline phosphatase (E). Asterisks in panel D indicate predicted positions of nonphosphorylated and monophosphorylated peptide (E). Ions at 3040.4 (D) and 2879.5 (E) correspond to sodiated forms of the diphosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptide, respectively.

Yeast GAL4 two-hybrid assay. The procedure used was essentially that of Song and Fields (10), as modified by Chevray and Nathans (3) and adapted by Wood et al. (61). Briefly, transformed yeast colonies were collected from the surface of the agar culture medium into 5 ml of Z buffer with no β-mercaptoethanol (10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.0]) (35). Cell densities were determined (A600), and a normalized amount from each culture was pelleted and suspended in 1 ml of the same buffer. The cells were lysed by four cycles of freezing and thawing.

β-Galactosidase activity in the clarified lysates was measured by conversion of ONPG→ONP (A420), and the values were converted to Miller units (35) for purposes of comparison. Although there was little deviation in replica measurements of the same samples within an experiment and the rank order of interacting pairs was generally the same, global differences in absolute values between experiments made it necessary to normalize the data before calculating standard error, as follows. For each experiment, wild-type pAP self-interaction values were averaged and divided into the overall lowest average to obtain a normalization factor. All data points within an individual experiment were then multiplied by the normalization factor for that experiment; the mean for all normalized data points was determined for each interacting pair; and the standard errors were calculated.

RESULTS

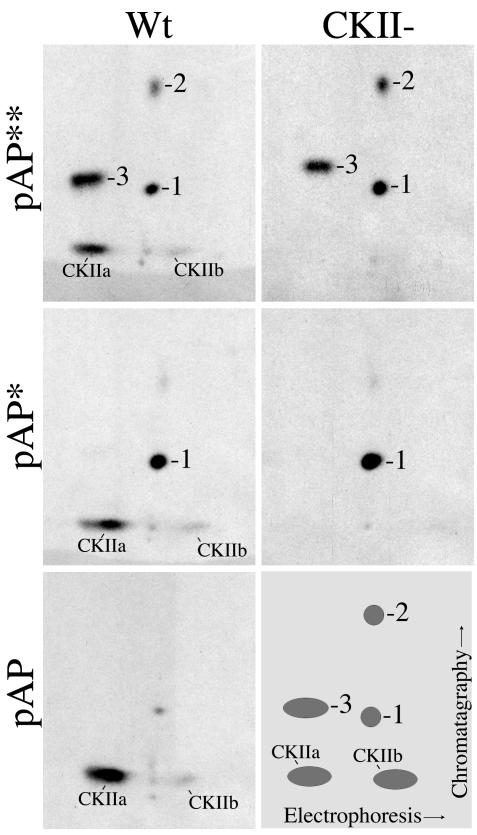

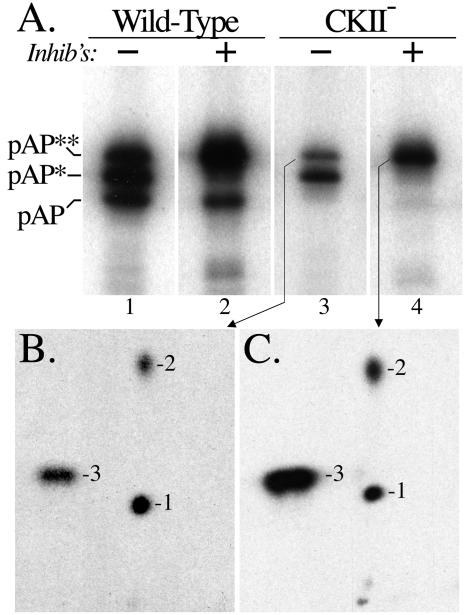

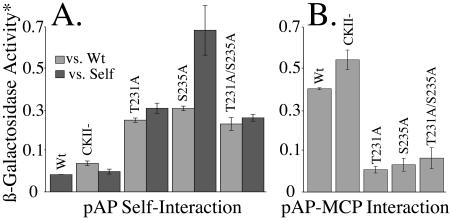

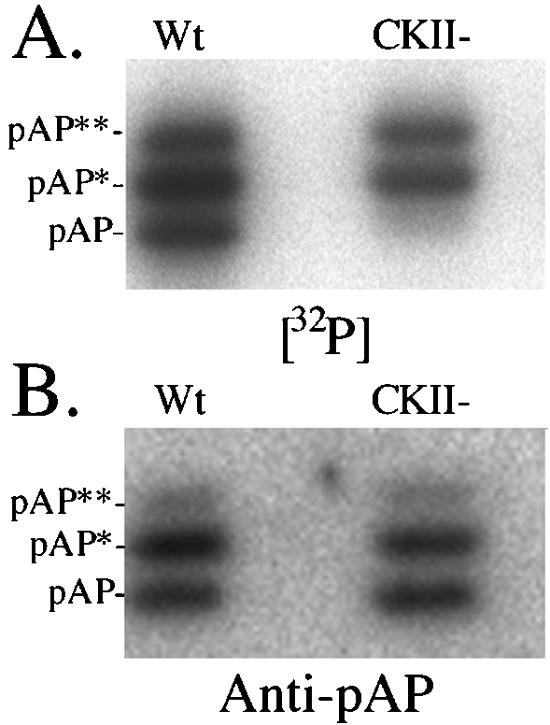

As shown here for reference, wild-type pAP resolves into three isoforms during SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). All three were phosphorylated on adjacent serines 156 and 157 in a CKII consensus sequence (43). Substituting alanines for these two serines eliminated pAP phosphorylation (Fig. 1A) but had no effect on the relative amounts of the three isoforms (Fig. 1B), as previously reported (43). The 32P remaining on pAP* and pAP** in the CKII− mutation is due to secondary-site phosphorylation (43). Identifying these sites was complicated by the heterogeneous phosphopeptide pattern that resulted when pAP* and pAP** were cleaved with trypsin (see reference 43 and Fig. 6 therein).

FIG. 1.

SCMV pAP resolves into three electrophoretic mobility isoforms during SDS-PAGE. Wild-type (Wt) and CKII− precursor assembly proteins were expressed, 32P labeled in transfected cells, recovered by immunoprecipitation in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrotransfer to PVDF Immobilon membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). (A) phosphorimage of the dried membrane showing the 32P-labeled radioactivity of each isoform. (B) Following radiodecay of the 32P (18 half-lives; undetected by phosphorimager), the membrane was probed with anti-N1 and then 125I-labeled protein A and phosphorimaged to determine the relative amount of each isoform.

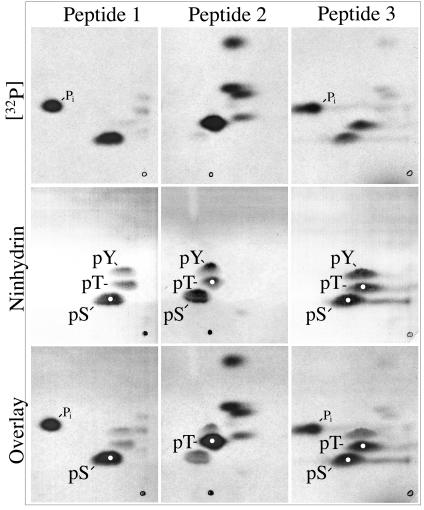

FIG. 6.

Identification of phosphorylated amino acids in pronase-derived phosphopeptides 1, 2, and 3 from pAP isoforms. 32P-labeled phosphopeptides from rBV KC34-expressed pAP** were prepared, hydrolyzed, and subjected to amino acid analyses as described in Materials and Methods. Shown here are fluorographic images prepared from the resulting thin-layer plates (top); direct images of the same plates sprayed with ninhydrin to detect the pThr (pT), pSer (pS), and pTyr (pY) standards added to each sample (middle); and composite images of the superimposed fluorographic and ninhydrin images (bottom). White dots indicate phosphoamino acid coincident with radioactivity in that sample. Two hydrolysates were analyzed per plate. The sample origin is seen as a spot or small circle at the bottom. Electrophoresis was left (+) to right (−), followed by ascending chromatography.

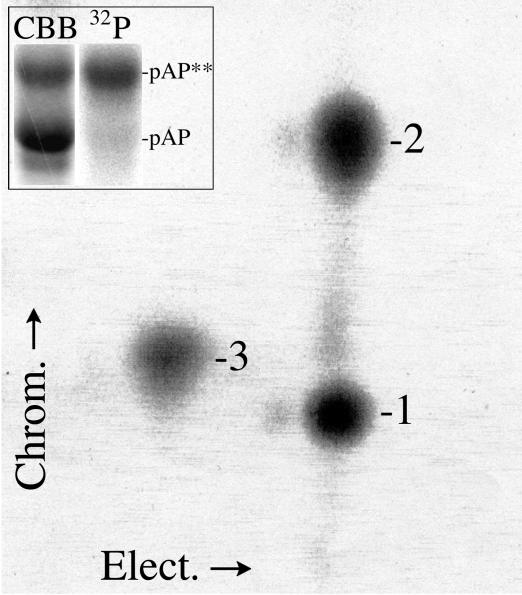

Pronase digestion reduces heterogeneity of secondary-site phosphopeptides.

Simpler phosphopeptide patterns were obtained from 32P-labeled pAP, pAP*, and pAP** with the less-specific protease, pronase (Fig. 2). The pAP isoform, which is phosphorylated only on Ser156 and Ser157 (43), has a predominant, hydrophilic phosphopeptide (Fig. 2) that is absent in the CKII− mutation (e.g., compare pAP* and pAP** patterns of the wild type and CKII−). The pAP* patterns differ from those of pAP by having an additional phosphorylated peptide, designated phosphopeptide 1; the pAP** patterns are distinguished by the presence of two more phosphopeptides, designated phosphopeptides 2 and 3 (Fig. 2). Peptide(s) 3 often resolved into multiple adjoining spots. As established below, phosphopeptides 1, 2, and 3 are interrelated, and some variability was observed in their relative abundance between preparations. The trace amount of peptide 1 in this pAP preparation (Fig. 4) reflects the difficulty of cleanly sectioning the closely spaced pAP and pAP* bands from the preparative gel.

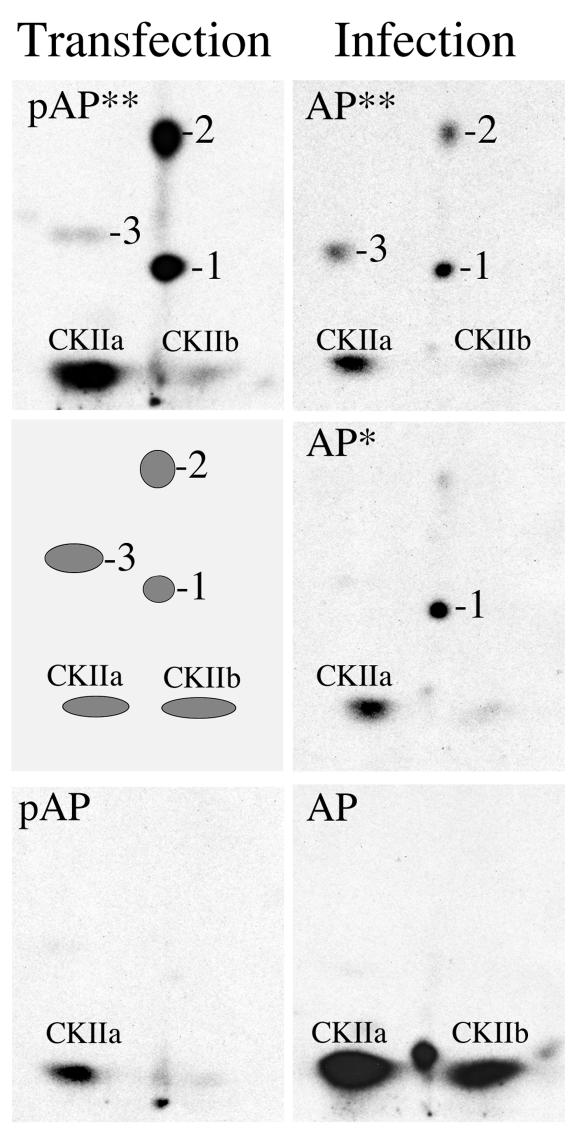

FIG. 2.

pAP isoforms have different phosphopeptide patterns. Wild-type (Wt) and CKII− precursor assembly proteins were expressed and 32P labeled in transfected cells, and the isoforms were immunoprecipitated in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to pronase cleavage and peptide analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Shown here are fluorographic images of the resulting thin-layer plates. In place of an image for CKII− pAP, which is not phosphorylated (e.g., Fig. 1A) (43), a schematic is presented showing the wild-type pAP** phosphopeptide designations (bottom right).

FIG. 4.

Phosphopeptide patterns of pAP isoforms from plasmid-transfected and AP isoforms from virus-infected cells are similar. Phosphopeptides were prepared from pAP isoforms immunoprecipitated from transfected cells (Transfection) and compared with those of AP isoforms recovered from infected cells (Infection), as described in Materials and Methods. Shown here are fluorographic images of the resulting thin-layer plates. With phosphatase inhibitors present, too little pAP* was recovered from transfected cells for peptide analysis; a schematic representation of the pAP** phosphopeptides is presented in its place. Phosphopeptide numbering is the same as that in Fig. 2.

Phosphatase inhibitors increase the amount of pAP**.

Variability in the relative amounts of pAP* and pAP** between different preparations of the wild-type protein suggested that phosphatase activity was a complication. To test this, two sets of cells were transfected to express either wild-type or CKII− pAP and radiolabeled with 32Pi. Both sets were processed for immunoprecipitation, one with phosphatase inhibitors present throughout and the other without inhibitors added. In the absence of inhibitors, all three wild-type isoforms were radiolabeled, pAP* being the most prominent (Fig. 3A, lane 1). As expected (Fig. 1) (43), only pAP* and pAP** were radiolabeled in the preparation of CKII− pAP, again with pAP* the more prominent (Fig. 3A, lane 3). However, when phosphatase inhibitors were used, pAP* was nearly undetectable and the intensity of pAP** was markedly increased (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 4), indicating that pAP* has a comparatively low abundance in the cell and increases by dephosphorylation of pAP** following cell lysis. The phosphopeptide patterns of pAP** from these preparations were qualitatively similar (Fig. 3B and C), but the relative intensities of peptides 2 and 3 were increased by the inhibitors, suggesting that they contain the most phosphatase-sensitive phosphate.

FIG. 3.

Phosphatase inhibitors increase the relative amount of pAP**. Wild-type and CKII− precursor assembly proteins were expressed, 32P labeled in transfected cells, and recovered by immunoprecipitation without (−) or with (+) phosphatase inhibitors present as described in Materials and Methods and Results. Following SDS-PAGE and electrotransfer to an Immobilon membrane, an autoradiogram was made of the resulting membrane (A). The pAP** bands were cut from a second gel containing the same preparations, and their phosphopeptide patterns were compared as described in Materials and Methods. Fluorographic images prepared from the resulting thin-layer separations of phosphopeptides from pAP** recovered without (B) or with (C) phosphatase inhibitors are shown. Phosphopeptide numbering is the same as that in Fig. 2.

Pattern of secondary-site phosphorylation is similar for pAP** in capsids recovered from CMV-infected cells.

To validate using pAP expression systems as models for studying pAP phosphorylation, we compared the phosphopeptide patterns of pAP isoforms expressed in transfected cells with those of the AP isoforms from virus-infected cells. We found that the pronase-phosphopeptide pattern of pAP** from transfected cells was qualitatively similar to that of AP** from infected cells (Fig. 4, top) and that the pAP and AP patterns were also similar, with possibly more of the CKIIb peptide present in the B-capsid preparation (Fig. 4, bottom). Phosphatase inhibitors present during immunoprecipitation of the transfected-cell proteins reduced the amount of pAP* below that needed for peptide analysis, but the pattern obtained for infected-cell AP* matched that obtained for pAP* in the absence of protease inhibitors (Fig. 2, middle left panel).

Secondary phosphorylation sites are Ser and Thr.

The amino acids phosphorylated in peptides 1, 2, and 3 were identified by 2-D separations of acid hydrolysates on cellulose thin-layer plates as described in Materials and Methods. To obtain enough protein for the assay, 32P-labeled CKII− pAP was expressed from BV KC34 and recovered as described in Materials and Methods. pAP** was the predominant 32P-labeled isoform obtained (Fig. 5, inset), and its pronase phosphopeptide pattern (Fig. 5) closely resembled that of CKII− pAP** from transfected cells (Fig. 2, top right panel). Fluorographic images identified the positions of 32P-labeled acid hydrolysis products, and subsequent staining with ninhydrin identified the positions of the phosphoamino acid markers. By overlaying the two images, it was determined that phosphopeptide 1 contains only pSer (Fig. 6A, bottom left), phosphopeptide 2 contains only pThr (Fig. 6B, bottom middle), and phosphopeptide 3 contains both pSer and pThr (Fig. 6C, bottom right).

FIG. 5.

pAP** expressed from rBV KC34 has a charasteristic pronase phosphopeptide pattern. 32P-labeled phosphopeptides were prepared from CKII− pAP** expressed in insect cells and analyzed by 2-D separation, as described in Materials and Methods. The inset shows the starting protein preparation recovered by Ni-immobilized metal affinity chromatography after SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) or autoradiography (32P) of the same gel lane. Shown here is a phosphorimage of the resulting phosphopeptide distribution. Phosphopeptides numbering is the same as that in Fig. 2.

Identification of Ser235 as secondary phosphorylation site.

Knowing (i) that secondary-site phosphorylation (i.e., mobility-shifting modification) is in the carboxyl half of pAP (51) and (ii) that the residues phosphorylated are Ser and Thr (Fig. 6), and reasoning (iii) that the heterogeneous pattern of hydrophobic peptides observed with trypsin is due to incomplete cleavage of a relatively hydrophobic sequence flanked by multiple Lys and Arg residues (43), we identified the 4,853-Da tryptic peptide (Gln217 to Lys267) as a candidate sequence to contain the secondary phosphorylation sites. It followed from the hypothesis that phosphorylation of the secondary sites causes the mobility shifts to pAP* and pAP** (43) and that mutations preventing phosphorylation at those sites would eliminate the isomers. Because phosphopeptide 1 in pAP* contains only pSer, we began by mutating the first two serines in the peptide, Ser235 and Ser241. These substitutions were made in the CKII− mutation to eliminate the background of Ser156 and Ser157 phosphorylation.

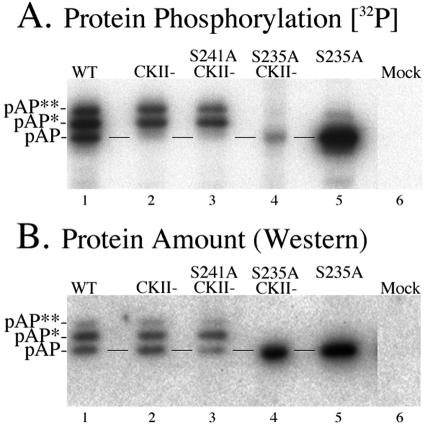

Changing Ser241 to Ala in the CKII− mutation had no noticeable effect on the amounts, electrophoretic mobilities, or phosphorylation of pAP* and pAP**, compared with those of the CKII− mutation (Fig. 7, lanes 2 and 3). However, changing Ser235 to Ala in the CKII− mutantion had dramatic effects. The pAP* and pAP** isoforms were not detected, the pAP isoform increased in amount, and phosphorylation was all but eliminated (Fig. 7, lanes 4). When S235A was introduced into wild-type pAP, two differences from the S235A/CKII− mutation were observed. First, the pAP isoform became phosphorylated, as expected from the presence of the CKII sites. Peptide mapping of the S235A 32P-labeled pAP band showed only the CKII phosphopeptides; phosphopeptides 1, 2, and 3 were absent (data not shown). Second, a weak band close to the mobility of pAP* was detected by radiolabeling (Fig. 7A, lane 5). Although there was insufficient 32P radioactivity for confirmatory phosphoamino acid analysis, based on data presented below, we suspect that this is a pAP mobility isomer resulting from aberrant phosphorylation of nearby Thr231 in the absence of Ser235. The increased amount of pAP in both S235A mutations (Fig. 7B, especially lanes 4 and 5) is consistent with an inability to convert pAP to isoforms pAP* and pAP**.

FIG. 7.

Patterns of pAP mobility isoforms for wild-type and mutant forms of the proteins. (A) 32P-labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors from cells expressing the wild type (WT) or the indicated mutations and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by electrotransfer to Immobilon membranes and phosphorimaging. (B) Once 32P radioactivity decayed below detectability by phosphorimaging, the membrane was subjected to Western immunoassay with anti-N1 and 125I-labeled protein A and phosphorimaged. Preparation of mock-transfected cells (Mock) was carried out in a noncontiguous lane and has been transposed in this collage. Lines between the lanes indicate the position of pAP.

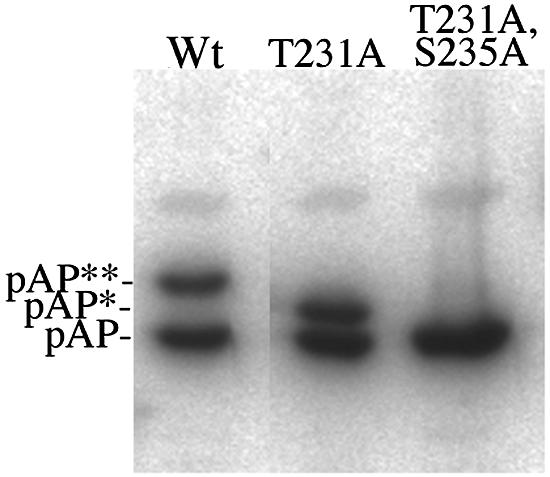

Further inspection of the amino acids flanking Ser235 revealed that it is within a MAP kinase consensus phosphorylation sequence (i.e., XXS/TP), and that its phosphorylation could provide the priming phosphate enabling GSK-3 to phosphorylate Thr231 four residues upstream (12). To test the possibility that Thr231 is a phosphorylation site, it was replaced by alanine. The resulting mutation (T231A) produced a band at the position of pAP* but not pAP** (Fig. 8). Analysis of the pAP* band established that it contains phosphopeptide 1, but not 2 and 3, and that peptide 1 contains only pSer (data not shown). When Thr231 and Ser235 were both changed to alanine, only the pAP isoform was made (Fig. 8), and it contained only the CKIIa and CKIIb phosphopeptides (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that phosphopeptide 1 contains pSer235, that the mobility shift from pAP to pAP* is due to phosphorylation at Ser235, and that appearance of pAP** and phosphopeptides 2 and 3 requires phosphorylation of Thr231.

FIG. 8.

Mutation of Thr231 eliminates only pAP**. Wild-type pAP (Wt) and the T231A and T231A/S235A mutations were expressed in transfected cells, harvested into 4× protein sample buffer at 70°C, and analyzed by Western immunoassay with anti-N1 and 125I-labeled protein A, following SDS-PAGE. Shown here is a phosphorimage of the resulting membrane. Preparation of the wild type took place in a noncontiguous lane and has been transposed in this collage.

Corroboration of secondary phosphorylation sites by mass spectrometry and sequence analysis.

With Thr231 and Ser235 implicated by mutational analysis as the phosphorylation sites, we sought to corroborate their identification by other methods. First, we used MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. A fragment containing both Thr231 and Ser235 (i.e., N′-Gln217-Glu245-C′) was prepared from 32P-labeled CKII− pAP as described in Materials and Methods. The procedure required isolating pAP** (Fig. 9A, fractions 27 and 28), digesting it with trypsin to give the fragment Gln217-Lys267 (Fig. 9B, fractions 33 and 34), and then cleaving the tryptic fragment with GluC to produce the Gln217-Glu245 fragment (Fig. 9C, fraction 61). Mass spectrometry of the material in fraction 61 of the final HPLC showed a predominant ion corresponding to the predicted peptide with two phosphates (Fig. 9D, 3017.9), consistent with two sites of phosphorylation in the fragment. No signal above background was detected at the positions of the predicted monophosphorylated (2938) or nonphosphorylated (2858) peptide. Alkaline phosphatase treatment of the peptide produced two new ions corresponding to the same fragment with either one (2937.2) or no (2857.5) phosphate (Fig. 9E), verifying that the mass difference between the predicted and observed peptide (i.e., 160 atomic mass units) is due to phosphates.

A second analysis subjected a portion of the same RP-HPLC-purified Gln217-Glu245 fragment to sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry, as described in Materials and Methods. The amino acid sequence determined was the same as that predicted from the nucleotide sequence, but observed masses for collision-induced fragments indicated that both Thr231 and Ser235 were phosphorylated and that only their phosphorylated forms were present in pAP** (sequencing data not shown).

The third experiment was intended to determine the relationship between Pronase phosphopeptides 1, 2, and 3. A pAP peptide containing the pThr231 and pSer235 (i.e., APAQLApTPVApSPTTTT240-Cys; Cys was appended for antibody preparation) was chemically synthesized and RP-HPLC purified. It was then cleaved with pronase, as described in Materials and Methods; combined with a comparatively small amount of RP-HPLC-purified, 32P-labeled, pronase-cleaved pAP (added as markers for phosphopeptides 1, 2, and 3) and subjected to 2-D separation on a thin-layer plate (Fig. 5). Phosphopeptides 1, 2, and 3 were located by phosphorimaging the 32P-labeled markers, the cellulose containing each phosphopeptide was scraped from the plate, the peptides were eluted into pH 1.9 peptide electrophoresis buffer, the samples were lyophilized, and the peptides were suspended in 0.1% TFA-water and subjected to sequencing by automated Edman degradation (ABI 492 protein sequencer; Applied Biosystems, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). Peptide 1 gave the sequence AXPTT, peptide 2 gave the sequence AXPV, and peptide 3 gave the sequence AXPVAXPTT, where X indicates absence of a recognized amino acid at that sequencing cycle, consistent with the presence of pThr and pSer, which are destroyed by the system chemistry. Thus, phosphopeptide 3 is composed of phosphopeptides 1 and 2, which pronase cleaves between Val233 and Ala234 (M. Kisic, R. Casaday, and W. Gibson, unpublished data).

Taken together, these sequencing data establish that Thr231 and Ser235 are both phosphorylated in the pAP** isoform and that phosphopeptide 3 is composed of phosphopeptides 1 (contains pSer235) and 2 (contains pThr231).

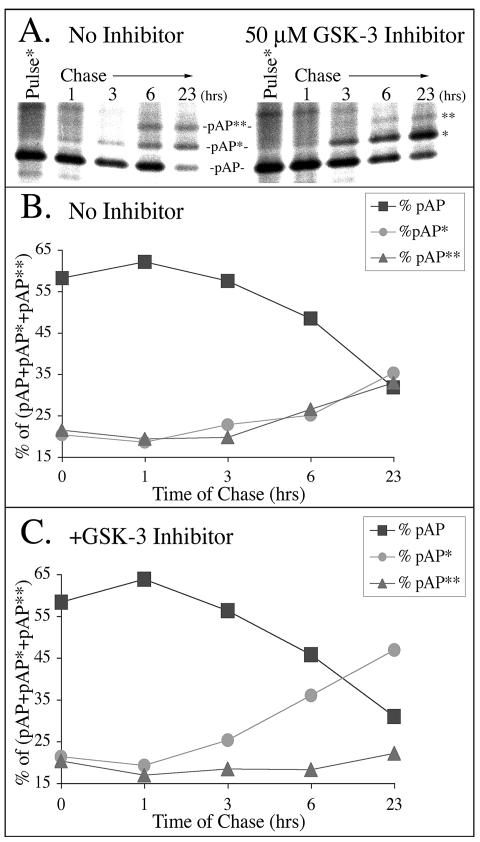

GSK-3 inhibitor reduces the relative amount of pAP** isoform.

As a more direct demonstration that GSK-3 phosphorylates Thr231, converting pAP* to pAP**, we did a pulse-chase radiolabeling experiment using a GSK-3-specific inhibitor. pAP made in transfected cells was pulse radiolabeled with [35S]methionine (ICN) for 30 min and then chased in the absence of radiolabel for up to 23 h, either without drug added or with 50 μM GSK-3 inhibitor (catalogue no. SB-415286; Tocris, Ellisville, Mo.). Samples taken at different times after labeling were collected, subjected to immunoprecipitation, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging (Fig. 10). The inhibitor selectively reduced the relative amount of the pAP** isoform, as expected if it is produced by GSK-3 phosphorylation of pAP* (Fig. 10). By the end of the chase period in the presence of inhibitor, the relative amount of pAP** had decreased ≈20% and the relative amount of pAP* had increased ≈20%, compared to those isoforms in nontreated cells (Fig. 10B and C). With or without the inhibitor, the relative amount of the pAP isoform decreased by ≈50% during the chase period. These data are consistent with pAP being converted to pAP*, which accumulates if GSK-3-mediated conversion of pAP* to pAP** is inhibited.

FIG. 10.

GSK-3 inhibitor selectively reduces relative amount of pAP**. [35S]methionine-labeled transfected-cell proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-C1 and subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging (A). Phosphatase inhibitors (catalogue no. 524625, Calbiochem) but no protease inhibitors were added to the lysis buffer, antiserum, and all immunoprecipitation solutions. In preparation for SDS-PAGE, proteins were solubilized in a solution containing six parts NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (catalogue no. NP0007; Invitrogen) and four parts 1 M dithiothreitol. Total radioactivity in the three pAP isoforms was measured for each time point, and the relative percentage of the total was calculated for each isoform. Shown here are the changes in the percentage of the total for each isoform from nontreated cells (B) and cells treated with GSK-3 inhibitor (C).

Acidic charges at positions Thr231 and Ser235 reduce electrophoretic mobility of pAP.

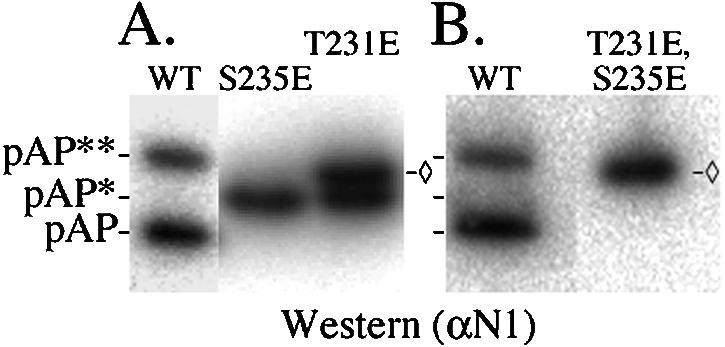

The correlation between phosphorylation of Thr231 and Ser235 and the appearance of mobility isomers pAP* and pAP** indicates that the added negative charges cause the mobility changes. This was tested by substituting Glu for each residue with the following results. Changing Ser235 to Glu converted all pAP to an electrophoretic mobility close to that of pAP*. There was no other isoform, indicating that Glu does not substitute for pSer in promoting phosphorylation at Thr231 to give pAP** (Fig. 11A). When Glu was substituted for T231, about half of the protein comigrated with pAP* and the rest migrated intermediate to pAP* and pAP** (Fig. 11A). Pronase digestion of this intermediate band showed phosphopeptide 1 (data not shown), indicating that it originates from the pAP*-like isoform of T231E by phosphorylation of S235. When both T231 and S235 were changed to Glu, all pAP was converted to the position of the upper band in mutant T231E, no additional mobility isomers were seen (Fig. 11B), and only phosphopeptides CKIIa and CKIIb were detected in pronase digestions of the 32P-labeled protein (data not shown). Thus, substituting an acidic residue for Thr231 and Ser235 approximates, but does not fully duplicate, the electrophoretic mobility shift to pAP** resulting from phosphorylation of those residues.

FIG. 11.

Substituting glutamic acid for Thr231 or Ser235 produces electrophoretically slower isomers of pAP. Cells were transfected to express pAP mutation T231E, S235E, or T231E/S235E. Four days later, the cells were harvested into 4× protein sample buffer at 70°C and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western immunoassay with anti-N1 and phosphorimaging, as described in Materials and Methods. Shown here is a phosphorimage of the resulting Immobilon membrane. ◊, position of T231E/S235E mutant isoform, as distinct from pAP**.

pAP interactions altered by mutating Thr231 and Ser235.

The yeast GAL4 two-hybrid assay has been used previously (5, 40, 61) to study the interaction of pAP with itself and with MCP. We used it here as an initial test for evidence that phosphorylation influences pAP function, because (i) yeasts have homologs of the protein kinases suspected to be acting on pAP (22, 25, 38), and (ii) it provides a comparatively simple, direct, and sensitive means of evaluating these specific protein-protein interactions (11). Three interactions were tested: heterologous interactions of wild-type pAP with the mutants, homologous interactions of wild-type and mutant pAPs with themselves, and interactions of MCP with either wild-type or mutant pAPs. All assays were repeated in their entirety at least three times.

Results of these assays, normalized as explained in Materials and Methods, showed that interactions of the phosphorylation mutants with themselves or with wild-type pAP were stronger than the interaction of wild-type pAP with itself (Fig. 12A). Among these, self interaction of mutant S235A was the strongest and interactions of the CKII− mutant were the weakest, approximating those of wild-type pAP self-interaction. The opposite order of interaction strengths was observed with MCP (Fig. 12B). Wild-type and CKII− pAP again behaved similarly; both interacted more strongly than mutations T231A, S235A, and T231A/S235A with MCP. Wild-type pAP versus itself gave the weakest self-interaction of all pAP combinations tested. Thus, when Thr231 and Ser235 were present and available for phosphorylation (i.e., wild-type and CKII−), pAP interacted poorly with itself but well with MCP. Changing these residues to Ala and making them unavailable for phosphorylation reversed these preferences, rendering pAP more strongly self-interactive and more weakly interactive with MCP.

FIG. 12.

Phosphorylation mutants show stronger interactions with self, but weaker interactions with MCP. Yeast GAL4 two-hybrid assays were done as described in Materials and Methods and Results to test the interaction of pAP phosphorylation mutants with themselves, wild-type pAP, and MCP. Data shown are averages ± standard errors (as described in Materials and Methods) from three separate experiments testing self-interaction (A) and three experiments testing interaction with MCP (B). Self interactions were between heterologous pairs, i.e., wild-type (Wt) pAP with mutant pAP, where lighter results indicate the left-hand bar for each mutant, or between homologous pairs, where darker areas indicate the right-hand bar for each protein. Wild-type pAP had no heterologous pair (A); the values for T231A/S235A versus MCP (B) were derived from two, rather than three, separate experiments. *, β-Galactosidase acitivity was calculated in Miller units (A420 × 1,000)/(min × 0.1 × concentration factor × optical density at 600 nm) (35).

DISCUSSION

Phosphorylation and proteolytic cleavage are two defining modifications of the CMV assembly protein precursor (pAP) and its homologs in other herpesviruses (17, 20, 27). Cleavage of pAP is now recognized as an essential step in capsid maturation and led to discovery of the herpesvirus maturational protease (19, 21, 44, 48). The significance of pAP phosphorylation has not been established, but the possibility that it too affects pAP function is of considerable interest. Our objective in the work described here was to identify the specific sites phosphorylated on pAP, as a step toward investigating the functional significance of this modification.

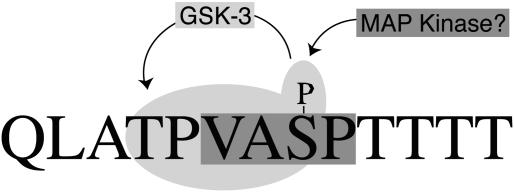

An earlier report showed that SCMV pAP is phosphorylated on two adjacent serines (Ser156 and Ser157) in a CKII consensus phosphorylation sequence (43). The same study provided evidence for at least two additional sites whose phosphorylation correlated with the appearance of electrophoretically slower-migrating isoforms, pAP* and pAP**. In the work described here, we identified these final two sites as Thr231 and Ser235 in overlapping GSK-3 and MAP kinase consensus phosphorylation sequences (Fig. 13). All four sites have been verified through phosphopeptide mapping, site-directed mutagenesis, and mass spectrometry.

FIG. 13.

Model showing the location of Thr231 and Ser235 within the pAP sequence containing consensus GSK-3 (light gray; includes GSK-3 priming phosphate) and MAP kinase (darker gray) phosphorylation sites.

Cellular enzymes can phosphorylate each site, as demonstrated by the finding that all phosphopeptides present in mature pAP from virus-infected cells are also present in pAP from transfected cells expressing no other viral proteins. The specific kinases implicated and evidence for their involvement are as follows. (i) Serines 156 and 157 are in a CKII consensus phosphorylation sequence (SerXXAsp/Glu) (29, 34) and, as expected for recognition by CKII (41), their phosphorylation was reduced by mutating the acidic amino acid three residues downstream (43). This site has apparent counterparts among all β-herpesvirus pAP homologs and is in a location that could influence the adjacent nuclear localization signals (reference 43 and Table 1 therein). (ii) Ser235 fits a general MAP kinase consensus sequence [e.g., (Ser/Thr)Pro] (39), but this assignment is ambiguous with cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2 (cdk2), which also has a proline-dependent recognition sequence [e.g., (Ser/Thr)ProX(Lys/Arg)] (36, 37). Potential counterparts of this putative MAP kinase site are present in all CMV subgroup pAP homologs except that of murine CMV, which does have a ThrGly pair as recognized in some MAP kinase sequences (32). The human herpesvirus 6 and human herpesvirus 7 homologs have an approximately colinear cdk2 site. (iii) Thr231 fits both MAP kinase and GSK-3 [e.g., (Ser/Thr)XXX(pSer/pThr)] (12, 13) consensus phosphorylation sequences, but the following evidence supports the conclusion that it is primarily a GSK-3 substrate.

First, and like many GSK-3 substrates requiring a priming phosphate on the P plus 4 residue (12, 13), Thr231 was not phosphorylated when the P plus 4 Ser was replaced with Ala (e.g., S235A) (Fig. 7, lanes 5). Substituting an acidic amino acid at position 235 (e.g., S235E) (Fig. 8) did not mimic the priming phosphate to enable phorphorylation of the GSK-3 site, as it does in some GSK-3 substrates (7). Second, and more compellingly, when pAP was expressed in the presence of a GSK-specific inhibitor, phosphorylation of Thr231 (i.e., amount of pAP**) was selectively reduced, as observed in vitro with GSK-3 synthetic peptide substrates (4), and the relative amount of pAP* increased correspondingly (Fig. 10). Accumulation of pAP* under conditions of GSK-3 inhibition is consistent with pAP* being a precursor of pAP** and phosphorylation of Ser235 preceding that of Thr231. Further, conversion of pAP* to pAP** appears to be efficient, since there was comparatively little pAP* detectable at a steady state (with phosphatase activity inhibited) (Fig. 3). The related findings that there is more pAP* than pAP** when phosphatase activity is not inhibited (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 3) and that the pAP* band contains no pThr suggests that the phosphate on Thr231 is comparatively more exposed and/or sensitive to phosphatases. The SCMV GSK-3 site has potential counterparts only among the pAP homologs of primate CMVs. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a GSK-3-phosphorylated viral structural protein.

We are interested in the possibility that the electrophoretic mobility shifts resulting from phosphorylation at Thr231 and Ser235 reflect conformational changes in pAP that have functional significance. The amino acid context of these phosphorylation sites is important for the mobility change, since adding phosphates to Ser156 and Ser157 does not cause a detectable shift under the same SDS-PAGE conditions (Fig. 1). In this connection, it may be relevant that Thr231 and Ser235 are situated next to prolines within a somewhat hydrophobic portion of the protein (i.e., PAQLATPVASPTT) where their phosphorylation could have disruptive effects. Serines 156 and 157, in contrast, are in a comparatively hydrophilic and already electronegative environment (i.e., ERDASSDEEEDMS). The magnitude of the charge at these positions is also important, since glutamic acids in place of both Thr231 and Ser235 (i.e., T231E/S235E; charge Δ, −2) approximated but did not duplicate the mobility shift caused by adding a phosphate to each residue (i.e., pT231/pS235; charge Δ, −4) (Fig. 11B).

With the phosphorylation sites identified, studies can proceed to determine the significance of these modifications. Although it is possible that one or more of the sites is phosphorylated as a bystander event of no functional importance, there are plausible roles for these modifications during infection ranging from tagging unwanted pAP for degradation to modulating key interactions of pAP (43, 61) to promoting pAP elimination from the maturing capsid. More specifically, we speculate that the enhanced pAP-MCP interaction resulting from pAP phosphorylation (Fig. 12B) could help stabilize pAP-MCP complexes during their nuclear translocation, oligomerization into protocapsomeres, and incorporation into procapsids. Conformation-induced changes in pAP resulting from its interaction with MCP could provide a mechanism for timely exposure of the phosphorylation sites. By extension, the same phosphorylations predicted to stabilize pAP-MCP complexes during procapsid formation may then serve to destabilize AP complexes during subsequent procapsid maturation. The weakened self-interaction of phosphorylated pAP (Fig. 12A) could promote dissociation of AP-containing scaffolding elements released from their interaction with MCP by maturational proteolytic cleavage of pAP→AP, aiding their elimination through the capsid shell. The added phosphate electronegativity could also help expel AP via charge repulsion by incoming DNA. These and other possibilities will be tested through phosphorylation-site mutant viruses being developed to determine the influence of pAP phosphorylation on capsid assembly and establish its importance to virus replication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Cole for peptide sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry; Jody Franklin for peptide synthesis and sequencing by automated Edman degradation; Monica Kisic for help with synthetic peptide sequencing during a research internship from Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru; and Jenny Borchelt for technical assistance with cells and gels. We also appreciatively acknowledge helpful comments and advice from many colleagues, including P. Desai, R. Huganir, S. Desiderio, T. Hunter, P. Cohen, and J. McGready.

E.J.B. and R.J.C. are students in the Biochemistry, Cellular, and Molecular Biology graduate program; S.R.K. was a student in the Pharmacology graduate program; and J.R.B. was an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University and is now in the Johns Hopkins Medical Scientist Training Program.

This work was aided by USPHS research grants AI13718 and AI32957 to W.G.; by resources of the Mid-Atlantic Mass Spectrometry Center, supported by USPHS grant GM54882 to R.J.C.; and by resources of the AB Mass Spectrometry/Proteomics Facility at JHMI with support from NCRR shared instrumentation grant 1S10-RR14702, the Johns Hopkins Fund for Medical Discovery, and the Institute for Cell Engineering; and by resources of the Medical School Protein/Peptide Facility.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1990. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Beaudet-Miller, M., R. Zhang, J. Durkin, W. Gibson, A. D. Kwong, and Z. Hong. 1996. Viral specific interaction between the human cytomegalovirus major capsid protein and the C-terminus of the precursor assembly protein. J. Virol. 70:8081-8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevray, P. M., and D. Nathans. 1992. Protein interaction cloning in yeast: identification of mammalian proteins that react with the leucine zipper of Jun. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5789-5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coghlan, M. P., A. A. Culbert, D. A. Cross, S. L. Corcoran, J. W. Yates, N. J. Pearce, O. L. Rausch, G. J. Murphy, P. S. Carter, L. R. Cox, D. Mills, M. J. Brown, D. Haigh, R. W. Ward, D. G. Smith, K. J. Murray, A. D. Reith, and J. C. Holder. 2000. Selective small molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 modulate glycogen metabolism and gene transcription. Chem. Biol. 7:793-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai, P., and S. Person. 1996. Molecular interactions between the HSV-1 capsid proteins as measured by the yeast two-hybrid system. Virology 220:516-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai, P., S. C. Watkins, and S. Person. 1994. The size and symmetry of B capsids of herpes simplex virus type 1 are determined by the gene products of the UL26 open reading frame. J. Virol. 68:5365-5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doble, B. W., and J. R. Woodgett. 2003. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell Sci. 116:1175-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn, W., P. Trang, U. Khan, J. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2001. RNase P-mediated inhibition of cytomegalovirus protease expression and viral DNA encapsidation by oligonucleotide external guide sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14831-14836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etzkorn, F. A., Z. Y. Chang, L. A. Stolz, and C. T. Walsh. 1994. Cyclophilin residues that affect noncompetitive inhibition of the protein serine phosphatase activity of calcineurin by the cyclophilin. cyclosporin A complex. Biochemistry 33:2380-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields, S., and O. Song. 1989. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 340:245-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fields, S., and R. Sternglanz. 1994. The two-hybrid system: an assay for protein-protein interactions. Trends Genet. 10:286-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiol, C. J., A. M. Mahrenholz, Y. Wand, R. W. Roeske, and P. J. Roach. 1987. Formation of protein kinase recognition sites by covalent modification of the substrate. Molecular mechanism for the synergistic action of casein kinase II and glycogen synthase kinase 3. J. Biol. Chem. 262:14042-14048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiol, C. J., A. Wand, R. W. Roeske, and P. J. Roach. 1990. Ordered multisite protein phosphorylation. Analysis of glycogen synthase kinase 3 action using model peptide substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6061-6065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrichs, W. E., and C. Grose. 1986. Varicella-zoster p32/p36 is present in both the viral capsid and the nuclear matrix of the infected cell. J. Virol. 57:155-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao, M., L. Matusick-Kuman, W. Hurlburt, S. F. DiTusa, W. W. Newcomb, J. C. Brown, P. J. McCann, I. Deckman, and R. J. Colonno. 1994. The protease of herpes simplex virus type 1 is essential for functional capsid formation and viral growth. J. Virol. 68:3702-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson, W. 1981. Structural and nonstructural proteins of strain Colburn cytomegalovirus. Virology 111:516-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson, W. 1996. Structure and assembly of the virion. Intervirology. 39:389-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson, W., M. K. Baxter, and K. S. Clopper. 1996. Cytomegalovirus “missing” capsid protein identified as heat-aggregable product of human cytomegalovirus UL46. J. Virol. 70:7454-7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson, W., A. Marcy, I. J. C. Comolli, and J. Lee. 1990. Identification of precursor to cytomegalovirus capsid assembly protein and evidence that processing results in loss of its carboxy-terminal end. J. Virol. 64:1241-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson, W., and B. Roizman. 1974. Proteins specified by herpes simplex virus. Staining and radiolabeling properties of B capsid and virion proteins in polyacrylamide gels. J. Virol. 13:155-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson, W., A. R. Welch, and M. R. T. Hall. 1995. Assemblin, a herpes virus serine maturational proteinase and new molecular target for antivirals. Perspect. Drug Discov. Des. 2:413-426. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustin, M. C., J. Albertyn, M. Alexander, and K. Davenport. 1998. MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1264-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall, M. R. T., and W. Gibson. 1997. Independently cloned halves of cytomegalovirus assemblin, An and Ac, can restore proteolytic activity to assemblin mutants by intermolecular complementation. J. Virol. 71:956-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong, Z., M. Beaudet-Miller, J. Burkin, R. Zhang, and A. D. Kwong. 1996. Identification of a minimal hydrophobic domain in the herpes simplex virus type 1 scaffolding protein which is required for interaction with the major capsid protein. J. Virol. 70:533-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter, T., and G. D. Plowman. 1997. The protein kinases of budding yeast: six score and more. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irmiere, A., and W. Gibson. 1983. Isolation and characterization of a noninfectious virion-like particle released from cells infected with human strains of cytomegalovirus. Virology 130:118-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irmiere, A., and W. Gibson. 1985. Isolation of human cytomegalovirus intranuclear capsids, characterization of their protein constituents, and demonstration that the B-capsid assembly protein is also abundant in noninfectious enveloped particles. J. Virol. 56:277-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karas, M., and F. Hillenkamp. 1988. Laser desorption ionization of proteins with molecular masses exceeding 10,000 daltons. Anal. Chem. 60:2299-2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennelly, P. J., and E. G. Krebs. 1991. Consensus sequences as substrate specificity determinants for protein kinases and protein phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15555-15558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, H. K., K. Takamiya, J. S. Han, H. Man, C. H. Kim, G. Rumbaugh, S. Yu, L. Ding, C. He, R. S. Petralia, R. J. Wenthold, M. Gallagher, and R. L. Huganir. 2003. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit is required for synaptic plasticity and retention of spatial memory. Cell 112:631-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, J. Y., A. Irmiere, and W. Gibson. 1988. Primate cytomegalovirus assembly: evidence that DNA packaging occurs subsequent to B capsid assembly. Virology 167:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis, T. S., P. S. Shapiro, and N. G. Ahn. 1998. Signal transduction through MAP kinase cascades. Adv. Cancer Res. 74:49-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, F., and B. Roizman. 1991. The herpes simplex virus 1 gene encoding a protease also contains within its coding domain the gene encoding the more abundant substrate. J. Virol. 65:5149-5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meisner, H., and M. P. Czech. 1995. Casein kiniase II (vertebrates), p. 240-242. In G. Hardie and S. Hanks (ed.), The protein kinase facts book, protein-serine kinases. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 35.Miller, J. H. 1977. Experiment 48. Assay of β-Galactosidase, p. 352-355. In J. H. Miller (ed.), Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Moreno, S., and P. Nurse. 1990. Substrates for p34cdc2: in vivo veritas? Cell 61:549-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norbury, C. 1995. Cdc2 protein kinase (vertebrates), p. 184-187. In G. Hardie and S. Hanks (ed.), The protein kinase facts book, protein-serine kinases. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 38.O'Rourke, S. M., I. Herskowitz, and E. K. O'Shea. 2002. Yeast go the whole HOG for the hyperosmotic response. Trends Genet. 18:405-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearson, G., F. Robinson, T. B. Gibson, B.-E. Xu, M. Karandikar, K. Berman, and M. H. Cobb. 2001. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr. Rev. 22:153-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelletier, A., F. Do, J. J. Brisebois, L. Lagace, and M. G. Cordingley. 1997. Self-association of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP35 is via coiled-coil interactions and promotes stable interaction with the major capsid protein. J. Virol. 71:5197-5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinna, L. A. 1990. Casein kinase 2: an “eminence grise” in cellular regulation? Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1054:267-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plafker, S. M., and W. Gibson. 1998. Cytomegalovirus assembly protein precursor and proteinase precursor contain two nuclear localization signals that mediate their own nuclear translocation and that of the major capsid protein. J. Virol. 72:7722-7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plafker, S. M., A. S. Woods, and W. Gibson. 1999. Phosphorylation of simian cytomegalovirus assembly protein precursor (pAPNG.5) and proteinase precursor (pAPNG1): multiple attachment sites identified, including two adjacent serines in a casein kinase II consensus sequence. J. Virol. 73:9053-9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preston, V. G., J. A. Coates, and F. J. Rixon. 1983. Identification and characterization of a herpes simplex virus gene product required for encapsidation of virus DNA. J. Virol. 45:1056-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston, V. G., F. J. Rixon, I. M. McDougall, M. McGregor, and M. F. Al Kobaisi. 1992. Processing of the herpes simplex virus assembly protein ICP35 near its carboxy terminal end requires the product of the whole of the UL26 reading frame. Virol. 186:87-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramirez, S. M., and R. J. Cotter. 2002. A novel approach for on-slide alkaline phosphatase digestion of previously analyzed samples, abstr. A021363. Presented at the 50th American Society for Mass Spectrometry Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics, Orlando, Fla.

- 47.Rixon, F. J. 1993. Structure and assembly of herpesviruses. Sem. Virol. 4:135-144. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robson, L., and W. Gibson. 1989. Primate cytomegalovirus assembly protein: genmome location and nucleotide sequence. J. Virol. 63:669-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 50.Scheidtmann, K.-H., E. Birgit, and W. Gernot. 1982. Simian virus 40 large T antigen is phosphorylated at multiple sites clustered in two separate regions. J. Virol. 44:116-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenk, P., A. S. Woods, and W. Gibson. 1991. The 45-kDa protein of cytomegalovirus (Colburn) B-capsids is an amino-terminal extension form of the assembly protein. J. Virol. 65:1525-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith, M. C., T. C. Furman, T. D. Ingolia, and C. Pidgeon. 1988. Chelating peptide immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography. A new concept in affinity chromatography for recombinant proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 263:7211-7215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steen, H., B. Kuster, and M. Mann. 2001. Quadrupole time-of-flight versus triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry for the determination of phosphopeptides by precursor ion scanning. J. Mass Spectrom. 36:782-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steven, A. C., and P. G. Spear. 1997. Herpesvirus capsid assembly and envelopment, p. 312-351. In W. Chiu, R. M. Burnett, and R. L. Garcea (ed.), Structural biology of viruses. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 55.Tanaka, K., H. Waki, Y. Ido, S. Akita, Y. Yoshida, and T. Yoshida. 1988. Protein and polymer analyses up to m/z 100,000 by laser ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2:151-153. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tatman, J. D., V. G. Preston, P. Nicholson, R. M. Elliott, and F. J. Rixon. 1994. Assembly of herpes simplex virus type 1 capsids using a panel of recombinant baculoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1101-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomsen, D. R., L. L. Roof, and F. L. Homa. 1994. Assembly of herpes simplex virus (HSV) intermediate capsids in insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses expressing HSV capsid proteins. J. Virol. 68:2442-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welch, A. R., L. M. McNally, M. R. Hall, and W. Gibson. 1993. Herpesvirus proteinase: site-directed mutagenesis used to study maturational, release, and inactivation cleavage sites of precursor and to identify a possible catalytic site serine and histidine. J. Virol. 67:7360-7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Welch, A. R., A. S. Woods, L. M. McNally, R. J. Cotter, and W. Gibson. 1991. A herpesvirus maturational protease, assemblin: identification of its gene, putative active site domain, and cleavage site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:10792-10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wood, L. J., M. K. Baxter, S. M. Plafker, and W. Gibson. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus capsid assembly protein precursor (pUL80.5) interacts with itself and with the major capsid protein (pUL86) through two different domains. J. Virol. 71:179-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yost, R. A., and C. G. Enke. 1977. Selected ion fragmentation with a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 100:2274-2275. [Google Scholar]