Abstract

A child was found to be excreting type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) with a 1.1% sequence drift from Sabin type 1 vaccine strain in the VP1 coding region 6 months after he was immunized with oral live polio vaccine. Seventeen type 1 poliovirus isolates were recovered from stools taken from this child during the following 4 months. Contrary to expectation, the child was not deficient in humoral immunity and showed high levels of serum neutralization against poliovirus. Selected virus isolates were characterized in terms of their antigenic properties, virulence in transgenic mice, sensitivity for growth at high temperatures, and differences in nucleotide sequence from the Sabin type 1 strain. The VDPV isolates showed mutations at key nucleotide positions that correlated with the observed reversion to biological properties typical of wild polioviruses. A number of capsid mutations mapped at known antigenic sites leading to changes in the viral antigenic structure. Estimates of sequence evolution based on the accumulation of nucleotide changes in the VP1 coding region detected a “defective” molecular clock running at an apparent faster speed of 2.05% nucleotide changes per year versus 1% shown in previous studies. Remarkably, when compared to several type 1 VDPV strains of different origins, isolates from this child showed a much higher proportion of nonsynonymous versus synonymous nucleotide changes in the capsid coding region. This anomaly could explain the high VP1 sequence drift found and the ability of these virus strains to replicate in the gut for a longer period than expected.

One of the initial premises that favored the prospects of global polio eradication was the fact that there were no known human chronic carriers of the virus. Humans are the only natural hosts for poliovirus, so in the absence of an animal reservoir, global eradication of the disease would necessary mean the complete elimination of circulating poliovirus. This postulate was soon challenged by the discovery of individuals with antibody deficiencies who were shown to excrete vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) for long periods of time (1, 26, 38). To date, 21 of such cases have been confirmed around the world. B-cell deficiency disorders associated with long-term poliovirus excretion include X-linked or sporadic agammaglobulinaemia and common variable immunodeficiency, which can remain undiagnosed for more than 5 years. Furthermore, long-term excretion of wild poliovirus has also been recently documented in two healthy siblings from whom type 1 wild poliovirus was isolated for a period of 6 months (17).

Immunocompetent individuals excrete poliovirus for short periods after vaccination with live attenuated oral polio vaccine (OPV). This excretion period rarely exceeds several weeks (2). However, as mentioned above, immunodeficient patients can excrete vaccine-derived polioviruses for several months and even several years (4, 8, 9, 14, 26, 28, 30). An individual in the United Kingdom is known to have been excreting Sabin 2-derived poliovirus for an estimated 20 years and is still excreting at present (30). Only 2 other of the 21 reported long-term excreters are known to be currently excreting poliovirus.

Derivatives of the Sabin live attenuated vaccine strains present in OPV have been classified into two broad categories for programmatic reasons (43). OPV-like viruses represent the vast majority of vaccine-related isolates and have close sequence relationships (>99% VP1 sequence identity) to the original OPV strains, whereas VDPVs, those strains showing ≤99% VP1 sequence identity to the parental Sabin strains, are rare. The sequence drift shown in VDPVs is indicative of prolonged replication of the vaccine strain either in one individual, as discussed above, or in the community (circulating VDPVs). Circulating VDPV strains can indeed be a potential source of poliomyelitis epidemics and occur in populations with low polio immunity and in the absence of wild poliovirus competitors. Examples of such events have recently been reported in Hispaniola (19), the Philippines (3), Egypt (44), and Madagascar (37). Other examples of possible VDPV circulation have been described in Belarus (24), Romania (12), and the Russian Federation (9). A single highly evolved type 3 VDPV strain has also been recently isolated from sewage in Estonia (6).

The prevalence of long-term poliovirus excretion among individuals with immunodeficiencies is not known, although a recent study involving 347 individuals with B-cell immune deficiencies in four different countries found no long-term excreters among them, which suggested that this could be a relatively rare phenomenon (13). There is currently no medical treatment available to interrupt poliovirus excretion from these patients, although a new antiviral drug, pleconaril, has been tried and proved successful in one instance (8). Several attempts to stop poliovirus replication by the United Kingdom patient have been carried out, including the use of oral immunoglobulin (Ig), human breast milk (rich in secretory IgA), and the drug ribavirin but have so far been unsuccessful (27). The drug pleconaril was not used in this case because isolates from this individual were resistant to the drug as shown in laboratory experiments (8).

As part of the surveillance for poliovirus in Ireland, we identified a type 1 VDPV strain isolated from a stool sample of a healthy child. The virus isolate showed a 1.1% sequence drift from the Sabin type 1 vaccine strain in the VP1 coding region. The child, who continued to excrete type 1 poliovirus for the following 4 months, was born and vaccinated in Zimbabwe and then traveled to Ireland, where poliovirus excretion was detected in a routine health check. Here we report the molecular and virological characterization of sequential poliovirus isolates from this unusual case. The results established that the child excreted poliovirus for an estimated 10 months after he was immunized with OPV. The relevance of this case and long-term poliovirus excretion in general is discussed in the context of the global polio eradication initiative.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case history.

The patient was a boy born in Zimbabwe in August 2001. He received his last dose of OPV in Zimbabwe in December 2001. The total number of vaccine doses taken is unknown. He arrived in Ireland in January 2002. A total of 28 fecal specimens for virological examination were obtained from 16 May 2002 to 25 February 2003 at approximately weekly intervals (Table 1). Serological investigation of a sample taken on 19 June 2002 confirmed normal levels of Igs (4.56-g/liter IgG, 0.65-g/liter IgA, and 1.31-g/liter IgM). The titers of poliovirus neutralizing antibodies were 1:1,445, 1:90, and 1:45 for poliovirus serotypes 1, 2, and 3, respectively. As in previous cases of long-term poliovirus excretion by immunodeficient individuals, excretion seemed to have ceased spontaneously without any medical intervention or any other apparent biological phenomenon.

TABLE 1.

History of virus isolations from the child in Irelanda

| Lab. no.b | Date of isolate (day/mo/yr) | Result | Cytopathic effect in cell line:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD | L20B | HEp2 | FRK | MRC-5 | |||

| 02V07578a | 16/05/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V08323 | 30/05/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V08760 | 07/06/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V09529 | 21/06/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 02V09540 | 24/06/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V09825 | 01/07/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V10201 | 09/07/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 02V10498 | 16/07/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not inoculated |

| 02V10764 | 23/07/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V10897 | 29/07/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 02V11214 | 06/08/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V11434 | 12/08/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V11770 | 20/08/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V11985 | 27/08/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V12280 | 03/09/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 02V12542 | 11/09/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V12721 | 16/09/2002 | Poliovirus 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 02V16374 | 30/10/2002 | Echovirus type 25 | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 02V16936 | 06/11/2002 | Echovirus type 25 | No | No | No | Not inoculated | Yes |

| 02V17510 | 13/11/2002 | No virus isolated | No | No | No | No | No |

| 02V17829 | 19/11/2002 | No virus isolated | No | No | No | No | No |

| 02R70166 | 25/11/2002 | Echovirus type 25 | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 02V18113 | 03/12/2002 | Echovirus type 25 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| 02V18865 | 16/12/2002 | No virus isolated | No | No | No | No | No |

| 03V00272 | 07/01/2003 | Adenovirus isolated | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 03V00579 | 13/01/2003 | No virus isolated | No | No | No | No | No |

| 03V01448 | 28/01/2003 | Adenovirus isolated | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 03V01808 | 04/02/2003 | Adenovirus isolated | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

All specimens were from feces.

Virus isolates that were sequenced are underlined.

Virus isolation.

The fecal specimens were processed at the National Polio Laboratory in Ireland according to standard protocols for virus isolation and characterization (43). Five different cell lines (RD, L20B, HEp-2c, FRK, and MRC-5) were used for virus isolation. Virological investigation identified poliovirus type 1 in the first 17 samples. No poliovirus was detected from 16 September 2004. As shown in Table 1, echovirus 25 and adenovirus were detected in some stool samples after poliovirus excretion ceased. Working poliovirus preparations were collected by growth of the viruses in HEp-2C cells at 36°C in minimal essential medium without fetal calf serum. Poliovirus vaccine strain Sabin type 1 was used as a reference in our experiments. Virus stocks were stored at −70°C.

ITD test.

Intratypic differentiation (ITD) assays are used to investigate the wild or vaccine origin of poliovirus field isolates. A monoclonal antibody (MAb)-based ITD neutralization test validated in a World Health Organization (WHO) collaborative study is used at the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC) (41). Neutralization with a mixture of Sabin-specific MAbs of the three poliovirus serotypes (NIBSC no. 955, 1233, and 889 for PV1, PV2, and PV3, respectively) was carried out as an additional typing reaction when isolates were serotyped in the standard neutralizing antibody test (43). A 1:30 dilution of the trivalent MAb-ascites mixture was used in the assay. If an isolate is neutralized by the MAb mixture, it is identified as Sabin-like. If an isolate is not neutralized, it is either a Sabin-related strain with antigenic drift at the epitope recognized by the Mab or it is a wild-type virus. To distinguish between these two possibilities, genomic ITD tests are required. When necessary, the nucleotide sequence of the entire genomic region coding for the VP1 capsid protein of the relevant poliovirus isolate is determined.

Reverse transcription, PCR, and nucleotide sequencing of poliovirus genomes.

Poliovirus RNA was purified from HEp2-c cell culture supernatants and used for reverse transcription and PCRs by standard procedures. Sequencing of the purified viral reverse transcription-PCR DNA products was carried out with the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer as specified by the manufacturer. Standard primers with Sabin sequences were used. Sequence data were stored as Standard Chromatogram Format (*.scf) files and analyzed with the Wisconsin Package version 10.0-UNIX (GCG) and AlignIRV11 (LI-COR) software. Capsid amino acid mutations were located on the Mahoney virion structure (16) with RasWin Molecular Graphics version 2.4 software (38a).

Temperature sensitivity.

Temperature sensitivity was assayed by comparison of plaque formation on HEp-2C cells at 35.0, 39.5, and 40.0°C as described before (32).

Neurovirulence in transgenic mice.

Tg21-Bx transgenic mice expressing the human poliovirus receptor were used for these experiments. Tg21-Bx mice are the product of crossing TgPVR21 mice (23) with BALB/c mice followed by repeated backcrossing of offspring with BALB/c mice, interbreeding, and selection by PCR screening of tail DNA. Mice are homozygous for PVR and class II IA b genes (H2&double_tag;d). The mice were inoculated intramuscularly (left hind limb) with 50 μl of 10-fold viral dilutions, and a daily clinical score was monitored for 14 days. The probit method was used to calculate the 50% paralytic dose (PD50).

Antigenic characterization.

The antigenic properties of the virus isolates were studied by a microneutralization assay using Sabin-specific MAbs corresponding to antigenic sites 1 to 4 as described before (34). One hundred 50% cell culture infective doses (CCID50s) of the challenge virus was used in the test. MAbs were used at 1:50 and 1:200 dilutions.

Titration of human sera for poliovirus neutralizing antibodies.

The procedure for titration of human sera for poliovirus neutralizing antibodies was performed as recommended by the WHO (43). The serum antibody titer was considered the highest dilution of serum that protected 50% of the cultures against 100 CCID50s of challenge virus. Antibody titers were expressed as reciprocals of that dilution in log2 values. The challenge virus dose preparation ± 100 CCID50s (range of 50 to 200) was confirmed by the Kärber formula.

RESULTS

Initial characterization of virus isolates.

Table 1 summarizes the history of virus isolations from the child under observation. The first isolate, no. 02v7578, was sent to the WHO Regional Reference Laboratory at NIBSC for intratypic differentiation as part of the routine surveillance process in Ireland. This strain was characterized as a type 1 non-Sabin-like poliovirus, since it was not neutralized by Sabin-specific MAbs in the ITD neutralization assay described above but was neutralized by polyclonal serum specific for type 1 and not with polyclonal sera against type 2 and 3 polioviruses (data not shown). Virus 02v7578 was therefore selected for further molecular and phenotypic analyses.

The genomic sequence of strain 02v7578 was initially determined between nucleotides 2435 and 3447, which includes the entire coding region for the VP1 capsid protein, the region normally used for poliovirus genotyping. Ten nucleotide changes (1.1%) with respect to Sabin type 1 virus were found in the VP1 coding region of 02v7578. A total of 28 stool samples taken at approximately weekly intervals were subsequently investigated for the presence of poliovirus. Poliovirus type 1 was isolated from the next 16 stool samples. No poliovirus isolates were found in the last 11 samples. The VP1 sequences of eight selected isolates covering the entire period of poliovirus excretion were determined. All isolates belonged to the same genotypic lineage and showed cumulative nucleotide mutations with time. Partial nucleotide sequence analysis in the nonstructural region (nucleotides 5820 to 6530) of these isolates was also performed to investigate the possibility of recombination with other polio or nonpolio human enteroviruses. All viruses showed Sabin type 1-related sequences in this region, indicating that no recombination had occurred during the period of virus excretion. The complete nucleotide sequences (from nucleotide 52 to the end) of the first (02v7578) and last (02v12721) isolates were determined and compared to that of the parental Sabin type 1 virus (Table 2). The results are analyzed in the next two sections.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid differences between 02v7578 and 02v12721 strains and Sabin 1 vaccine virus

| Region | Nucleotide

|

Amino acid

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Sabin 1 | 02v7578 | 02v12721 | Position | Sabin 1 | 02v7578 | 02v12721 | |

| 5′ NCR | 344 | U | C | C | ||||

| 377 | U | U | C | |||||

| 480 | G | A | A | |||||

| 647 | G | A | A | |||||

| 675 | C | U | U | |||||

| VP4 | 856 | U | C | C | ||||

| 949 | C | U | U | |||||

| VP2 | 970 | C | U | U | ||||

| 1222 | C | C | U | |||||

| 1321 | A | G | G | |||||

| 1334 | G | G | A | 129 | Glu | Glu | Lys | |

| 1373 | C | U | U | 142 | His | Tyr | Cys | |

| 1374 | A | A | G | |||||

| 1423 | G | G | A | |||||

| 1439 | G | A | A | 164 | Asp | Asn | Asn | |

| 1442 | G | A | A | 165 | Asp | Asn | Asn | |

| 1453 | A | G | G | |||||

| 1467 | G | A | A | 173 | Arg | Lys | Lys | |

| 1658 | U | C | C | |||||

| 1661 | A | G | G | 238 | Asn | Asp | Asp | |

| 1671 | G | A | A | 241 | Ser | Asn | Asn | |

| 1682 | C | U | U | 245 | Pro | Ser | Ser | |

| VP3 | 1795 | C | U | U | ||||

| 1804 | U | C | C | |||||

| 1939 | U | C | C | |||||

| 1945 | A | A | U | 60 | Lys | Lys | Asn | |

| 2003 | G | A | A | 80 | Asp | Asn | Asn | |

| 2155 | G | A | A | |||||

| 2243 | C | U | U | |||||

| 2355 | G | A | A | 197 | Arg | Lys | Lys | |

| 2395 | C | U | U | |||||

| 2438 | A | U | U | 225 | Met | Leu | Leu | |

| 2446 | U | U | C | |||||

| VP1 | 2741 | G | G | A | 88 | Ala | Ala | Thr |

| 2746 | U | C | C | |||||

| 2776 | G | U | U | 99 | Lys | Asn | Asn | |

| 2778 | A | G | G | 100 | Asn | Ser | Ser | |

| 2781 | A | U | C | 101 | Lys | Met | Thr | |

| 2785 | U | C | C | |||||

| 2795 | A | G | G | 106 | Thr | Ala | Ala | |

| 2827 | C | U | U | |||||

| 2956 | C | C | U | |||||

| 2980 | C | U | U | |||||

| 3065 | G | G | A | 196 | Val | Val | Ile | |

| 3253 | A | A | G | |||||

| 3316 | C | U | U | |||||

| 3371 | G | A | A | 298 | Asp | Asn | Asn | |

| 2A | 3491 | A | G | G | 36 | Asn | Asp | Asp |

| 3559 | C | U | U | |||||

| 3595 | C | U | U | |||||

| 3604 | A | A | G | |||||

| 3785 | A | G | G | 134 | Thr | Ala | Ala | |

| 3802 | G | A | A | |||||

| 2B | 3856 | A | A | G | ||||

| 3961 | C | U | U | |||||

| 4027 | C | C | U | |||||

| 4093 | U | U | C | |||||

| 4094 | G | A | A | 88 | Val | Ile | Ile | |

| 2C | 4330 | U | C | C | ||||

| 4519 | A | C | C | |||||

| 4867 | U | C | C | |||||

| 3A | 5164 | U | C | C | ||||

| 5341 | U | U | C | |||||

| 5350 | C | U | U | |||||

| 5353 | A | G | G | |||||

| 3B | 5422 | G | A | A | ||||

| 3C | 5449 | C | C | U | ||||

| 5536 | C | C | U | |||||

| 5554 | C | U | U | |||||

| 5590 | C | U | U | |||||

| 5908 | C | U | U | |||||

| 3D | 5992 | A | A | C | 2 | Glu | Glu | Asp |

| 5993 | A | A | G | 3 | Ile | Ile | Val | |

| 6127 | U | U | C | |||||

| 6187 | C | U | U | |||||

| 6190 | U | C | C | |||||

| 6203 | C | C | U | 73 | His | His | Tyr | |

| 6349 | A | G | G | |||||

| 6451 | G | G | A | |||||

| 6598 | G | A | A | |||||

| 6961 | C | U | U | |||||

| 7072 | A | A | G | 362 | Ile | Ile | Met | |

| 7102 | A | A | G | |||||

| 7283 | C | U | U | |||||

| 3′ NCR | ||||||||

Molecular sequence evolution.

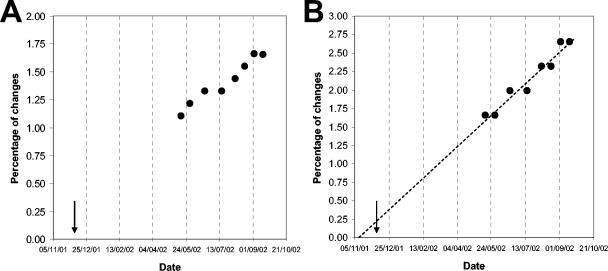

As mentioned above, sequence comparisons in the genomic region coding for the VP1 capsid protein are commonly used for the genotypic analysis of poliovirus isolates and to measure sequence evolution within genotypic lineages. Figure 1 shows the accumulation of changes in the VP1 genomic region of eight sequential poliovirus type 1 isolates excreted by the child under study. The number of nucleotide mutations is expressed as the percentage of changes with respect to the Sabin type 1 genome. The data were adjusted to linear functions for the accumulation of synonymous substitutions (y = 0.0086x + 0.2207; R2 = 0.95) or synonymous plus nonsynonymous changes (y = 0.0045x + 0.4093; R2 = 0.95). The rates of sequence evolution were estimated at 3.36 and 2.05% nucleotide substitutions/year, respectively. The date of initial infection was calculated by extrapolating the line for the evolution rate of synonymous substitutions back to zero in the Sabin 1 VP1. This date was estimated at around 10 November 2001, very much compatible with the actual date of the last known vaccination received by the child in December 2001.

FIG. 1.

Accumulation of changes in the VP1 genomic region of type1 isolates from the Irish child during the period of excretion. (A) Percentage of synonymous plus nonsynonymous mutations with respect to Sabin type 1. (B) Percentage of nucleotide changes in synonymous third-base codon positions with respect to Sabin type 1. The evolution rate was extrapolated back (dashed line) to zero substitutions in the Sabin 1 VP1. The arrow indicates the date of vaccination (day/month/year). For details, see the text.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence analysis.

The complete nucleotide sequences (from nucleotide 52 to the end) of the first (02v7578) and last (02v12721) poliovirus isolates were determined and analyzed to establish their respective predicted amino acid sequences. Table 2 shows the sequence differences with respect to the Sabin type 1 vaccine strain.

Five mutations were found in the 5′ noncoding region (NCR) of the isolates at positions 344, 377 (only in strain 02v12721), 480, 647, and 675. The mutation at nucleotide 480 in domain V of the 5′ NCR is a straight reversion to the sequence present in Sabin type 1 wild-type parental virus, the Mahoney strain and is commonly found in isolates from vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) patients and healthy vaccinees (12, 25, 33). This mutation restores an A-U base pair present in Mahoney strengthening the predicted base pairing of the stem structure in domain V (39) and has been associated with the attenuation phenotype of the vaccine strain (7, 18, 29, 36). The mutation found at nucleotide 377 could have a similar effect by strengthening a base pair (U · G to C-G) in the predicted secondary structural domain IV (39). Nucleotide 344 is located in a predicted loop structure at the tip of domain IV and is unlikely to have an effect on base pairing and secondary structure of the 5′ NCR (39). Nucleotides 647 and 675 mapped in the hypervariable region of the 5′ NCR outside the structural domains (39).

The distribution of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in the coding region of both 02v7578 and 02v12721 VDPV strains was unusual, with a very high proportion of nonsynonymous mutations found in the genomic region coding for the capsid proteins. Table 3 shows a comparison with previously characterized Sabin-related type 1 VDPV isolates of various origins. The proportion of nonsynonymous changes in the capsid region of both isolates from Ireland was significantly higher (more than 100%) than in any other type 1 VDPV known to date.

TABLE 3.

Molecular properties of type 1 VDPV strains

| Virus strain | VP1 drift from Sabin 1 (%) | Proportion of nonsynonymous changes (%)

|

Source | Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsid region | Nonstructural region | ||||

| 1-IIs | 1.1 | 20.8 | 15.0 | VAPP | 12 |

| M | 9.6 | 17.6 | NAa | iVAPPb | 22 |

| m | 10.0 | 16.0 | NA | iVAPP | 22 |

| IS1 | 5.3 | 19.2 | 13.4 | iVAPP | 4 |

| IS2 | 9.2 | 16.3 | 12.1 | iVAPP | 4 |

| 2090 | 2.6 | 22.7 | NA | Polio outbreak | 19 |

| 2091 | 2.0 | 18.0 | NA | Polio outbreak | 19 |

| 14 | 2.6 | 22.7 | 6.1 | VAPP | 9 |

| 7578 | 1.1 | 48.4 | 17.4 | Healthy | This paper |

| 12721 | 1.7 | 46.3 | 19.4 | Healthy | This paper |

NA, not available.

iVAPP, VAPP case in immunodeficient individual.

Fifteen- and 19-amino-acid mutations were found in the capsid region of the 02v7578 and 02v12721 strains, respectively. Most mutations were located on the external surface of the virus particle. Mutations at VP1-88, VP1-99, VP1-100, VP1-101, and VP1-106 were located at or close to the VP1 BC loop, which constitutes antigenic site 1 (16). A mutation at VP1-99 (from Lys to Asn) eliminated a trypsin cleavage site characteristic of Sabin type 1 (10). Amino acid substitutions were also found at antigenic site 2b (residues VP2-164, VP2-165, and VP2-173), antigenic site 3a (VP1-298), and antigenic site 3b (VP3-60) (31). Mutations at VP3-80 and VP3-197 mapped on the border of antigenic site 4. The three mutations at VP2-238, VP2-241, and VP2-245 clustered near the threefold axis of symmetry at the interface between VP2 and VP3 capsid proteins (16). Amino acid VP2-142, which mutated from His in Sabin type 1 to Tyr in strain 02v7578 and to Cys in isolate 02v12721, was located in the south rim of the canyon in a region that contacts the cell receptor (5, 15). VP1-196 was located at the floor of the conserved hydrophobic pocket, which is normally occupied by an endogenous lipid and where drugs that prevent virus uncoating are inserted (35). Mutations at VP2-129 and VP3-225 occurred in domains internalized in the native virion. Four of the capsid mutations at VP1-88 (Ala to Thr), VP1-106 (Thr to Ala), VP2-165 (Asp to Asn), and VP3-225 (Met to Leu) were direct reversions to the parental Mahoney sequence. Fewer mutations were found in nonstructural polypeptides. Two mutations were found in the protease 2A at positions 2A-36 and 2A-134; one change was identified in protein 2B at residue 2B-88 and another in the polymerase 3D at amino acid 3D-73, which is a straight reversion to the sequence found in the Mahoney wild-type strain. Three additional mutations were found in the polymerase 3D of strain 02v12721, at residues 3D-2, 3D-3, and 3D-362.

Temperature sensitivity and neurovirulence.

The results for the temperature sensitivity and neurovirulence of isolates from the child under observation are shown in Table 4. There was a gradual loss of the temperature sensitivity typical of the Sabin type 1 vaccine strain towards the non-temperature-sensitive phenotype of Mahoney wild-type virus. All isolates showed increased levels of neurovirulence similar to those of the Mahoney strain as determined by PD50 measurements in Tg21-Bx mice expressing the human poliovirus receptor.

TABLE 4.

Temperature sensitivity and neurovirulence of the virus isolates from Ireland

| Virus | Log titer reduction from:

|

Neurovirulence in Tg21-Bx

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 to 39.5°C | 35 to 40.0°C | Dose (log CCID50/ml) | No. of clinically affected mice/total | PD50a | |

| Sabin 1 | >5.0 | >5.0 | 8.6 | 6/8 | ∼8.3 |

| 02v7578 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 8/8 | 5.7 (5.4-6.1) |

| 5.5 | 2/8 | ||||

| 4.5 | 0/8 | ||||

| 02v9529 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 7.5 | 8/8 | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) |

| 6.5 | 8/8 | ||||

| 5.5 | 0/8 | ||||

| 02v11214 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 6.5 | 8/8 | 5.0 (4.6-5.3) |

| 5.5 | 7/8 | ||||

| 4.5 | 1/8 | ||||

| 3.5 | 0/8 | ||||

| 02v12721 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 6.5 | 8/8 | <6.5 |

| Mahoney | 0.0 | 0.1 | 7.0 | 13/16 | 5.9 (5.4-6.6) |

| 6.0 | 4/8 | ||||

| 5.0 | 3/16 | ||||

| 4.0 | 1/8 | ||||

| 3.0 | 0/8 | ||||

Estimates of the PD50 with associated 95% confidence intervals (in parentheses) were calculated by the probit method.

Antigenic properties.

The antigenic properties of the virus isolates from Ireland were determined by studying their reactivity with a panel of MAbs of known specificities. The results are shown in Table 5. None of the virus isolates reacted with antibodies specific for antigenic sites 1 and 3. Antigenic sites 2 and 4 were partially affected, since some but not all antibodies specific for those sites neutralized virus infectivity. All four virus isolates showed identical neutralization profiles with this panel of MAbs. The results were consistent with the observed amino acid changes at the predefined antigenic sites (see results above).

TABLE 5.

Reactivity of selected Irish isolates with specific Sabin 1 MAbs

| Strain | Reactivity with antibody toa:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1

|

Site 2

|

Site 3

|

Site 4

|

|||||||

| 955 | 956 | 425 | 429 | 237 | 430 | 423 | 958 | 234 | 1585 | |

| 02V7578 | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 02V9529 | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 02V11214 | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 02V12721 | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| Sabin 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ and −, neutralization or not, respectively, of infection of HEp-2C cells with 100 CCID50s of virus at a 1:50 dilution of antibody, as described in reference 34.

Neutralization assays with human sera.

The titer of neutralizing antibodies against strain 02v12721 in sera from United Kingdom healthy individuals was determined and compared to that against the Sabin type 1 vaccine strain. The titers also included a serum sample (no. 2A14743) collected from the child on 19 June 2002. The neutralization titers were slightly lower against the VDPV strain (data not shown), confirming the differences in some neutralizing epitopes between the two strains. However all sera tested showed good levels of neutralizing antibodies against the VDPV strain. The serum sample from the child under study contained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against both Sabin type 1 and strain 02v12721 (see “Case history” in Materials and Methods).

DISCUSSION

The known fact that live attenuated polioviruses present in the OPV given to millions of children around the world can evolve towards highly drifted and potentially dangerous revertant poliovirus strains is the cause of concern among scientists and epidemiologists working to achieve the complete eradication of paralytic poliomyelitis. Here we report the isolation and characterization of type 1 VDPV isolates from an unexpected source, a healthy African child.

During the time under observation, the child enjoyed excellent health and showed normal levels of Igs and high levels of serum neutralizing antibodies against all three poliovirus serotypes. Sequence comparisons through the VP1 coding region of serial isolates from this child confirmed that he had most likely excreted poliovirus from 6 months previous to the first virus isolation for a total period of 10 months of virus excretion following his immunization with OPV. This case can be considered exceptional, since poliovirus excretion by healthy children following vaccination with OPV is believed to rarely exceed 10 weeks (2, 42).

When only mutations at VP1 synonymous third-base codon positions were considered during the sequence analysis, a molecular clock of sequence evolution “ticking” at 3.36% nucleotide substitutions/year was identified. This result was remarkably similar to previous estimates of sequence evolution described for wild polioviruses and other VDPVs (11, 21, 22, 28) and was used to estimate the origin of infection at a date that was compatible with the last known date of vaccination received by the child. Although our results strongly support this view, other possible scenarios for the initial infection, although unlikely, cannot be completely ruled out. These could include an earlier immunization dose received after birth or infection from another individual either in Zimbabwe or Ireland.

The majority of synonymous mutations are expected to be phenotypically neutral and not under strong selection pressure, thus representing more accurately the real “age” of a virus. Silent mutations found in different highly evolved derivatives of Sabin 1, including those described here, overlap to only a small extent, supporting the above notion.

The estimate of the sequence evolution rate was rather different when all synonymous plus nonsynonymous changes were considered. The resulting evolution rate of 2.05% nucleotide substitutions/year was significantly higher than previous estimates of ∼1% nucleotide substitutions/year (11, 21, 22, 28). This difference was due to the very high proportion of nonsynonymous nucleotide changes present in the capsid coding region of the genomes of the isolates from Ireland, which was more than double of that of any other type 1 VDPV strain characterized to date. Remarkably, almost half of the nucleotide mutations found in the capsid region of the Irish isolates were coding changes. The fact that the synonymous molecular clock and the proportion of amino acid changes in the nonstructural region appeared to be normal suggests that this phenomenon cannot be easily explained by the existence of a higher-than-usual viral RNA mutation rate but rather by the selection of viruses with specific capsid amino acid sequences.

The vast majority of capsid amino acid changes are located at the external surface of the virus particle—many involving antigenic sites—which indicates that, at least in part, the observed high proportion of capsid amino acid mutations may have been driven by immune pressure. The changes in antigenic makeup were more extensive than in other highly evolved type 1 VDPV strains and involved, to a different extent, all known antigenic sites defined by murine MAbs, including antigenic site 3a, believed to be more stable (9, 31). However, changes in antigenic sites found in the isolates did not significantly modify the overall virus structure, since antibodies in human sera readily neutralized virus infectivity of strain 02v12721, giving neutralizing titers known to be protective against virus infection.

Mutations were also identified in residues known to be involved in receptor interactions and host range. Some of these amino acid changes may contribute to attenuation and temperature sensitivity by influencing the interaction of poliovirus with its cell receptor and the subsequent conformational changes that lead to virus cell entry (5, 7, 15, 16, 35).

Indeed, amino acid mutations accumulated in the Irish isolates led to changes in their virological properties, such as antigenic structure, neurovirulence, and temperature sensitivity, which changed towards full reversion to properties characteristic of the Sabin type 1 wild-type poliovirus parent, the Mahoney strain. The mechanisms of attenuation and temperature sensitivity of Sabin type 1 vaccine strain are known to involve several mutations (7, 18, 29, 36), many of them located in the capsid proteins. Several of those mutations reverted to wild-type Mahoney sequences in the VDPV strains analyzed in this study, most likely contributing to the observed phenotypes. Reversion at capsid residues such as VP1-88, VP1-106, and VP3-225 could be the consequence of adaptation of Sabin type 1 vaccine strain for growth in the human gut, since these changes are commonly found in isolates from VAPP patients, circulating VDPVs and VDPVs from immunodeficient individuals (4, 7, 9, 12, 19, 22, 25). The fact that many of the other capsid mutations, such as those at VP1-99, VP1-100, VP1-101, VP2-142, VP2-165, VP2-245, VP3-60, and VP3-80, were not infrequently found in other evolving lineages of Sabin 1 or related viruses indicates that they may also confer some selective advantage(s) but does not explain why a large number of amino acid mutations accumulated in these strains in such a relatively short period of time.

Mutations at nonstructural amino acids of possible relevance found in the Irish isolates included those of protease, 2A-36 and 2A-134; that of protein, 2B-88; and that of polymerase, 3D-73. All four residues mutated in most of the known highly evolved type 1 VDPVs either by direct mutation or recombination with another poliovirus or the nonpoliovirus enterovirus (4, 9, 12, 19). The mutation at position 3D-73 found in Sabin type 1 has been associated with temperature sensitivity of the vaccine strain and, to a limited extent, to its attenuation phenotype (7, 29, 40).

Following the recent poliomyelitis outbreaks associated with evolved VDPVs in Hispaniola (19), the Philippines (3), Egypt (44), and Madagascar (37), the search for VDPV strains has become an important part of the routine surveillance for wild polioviruses within the global eradication initiative (20). The laboratories of the WHO Polio Network have adequate tools to rapidly identify such strains, which involve both methods based on viral nucleotide sequence differences and tests to determine viral antigenic properties. Furthermore, isolates from VDPV outbreaks have been identified as recombinant polioviruses containing drifted vaccine-derived sequences in the capsid coding region and sequences of unidentified enteroviral origin spanning most of the nonstructural genomic region (3, 19, 37, 44). None of the known VDPV strains from immunodeficient individuals, isolated cases of VAPP, or environmental samples have been found to contain similar “foreign” sequences. However, the possible biological contribution of these heterotypic sequences to increased virus transmissibility has not yet been proven.

Although some poliomyelitis outbreaks due to VDPV strains could have occurred unnoticed during the 40 years of vaccination with OPV, these events are considered rare and are easily prevented and corrected by maintaining high levels of vaccination coverage and efficient surveillance for the disease. However, the existence of VDPV strains creates a vaccination paradox, particularly in countries where wild poliovirus has long been eradicated, since both interruption and continuation of vaccination can prevent the progress of vaccine viruses towards VDPV strains. This paradox would need to be addressed once wild poliovirus has been globally eradicated in order to devise adequate immunization policies for the posteradication era and, eventually, to be able to end polio vaccination completely. The use of a world-scale coordinated OPV immunization campaign, a switch to the use of inactivated poliovaccine for an interim period, or even the use of newly developed improved live attenuated vaccine strains have all been considered as possible alternatives to face this challenge (42).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abo, W., S. Chiba, T. Yamanaka, T. Nakao, M. Hara, and I. Tagaya. 1979. Paralytic poliomyelitis in a child with agammaglobulinemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 132:11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, J. P., Jr., H. E. Gary, Jr., and M. A. Pallansch. 1997. Duration of poliovirus excretion and its implications for acute flaccid paralysis surveillance: a review of the literature. J. Infect. Dis. 175(Suppl. 1):S176-S182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 2001. Acute flaccid paralysis associated with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus—Philippines, 2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:874-875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellmunt, A., G. May, R. Zell, P. Pring-Akerblom, W. Verhagen, and A. Heim. 1999. Evolution of poliovirus type I during 5.5 years of prolonged enteral replication in an immunodeficient patient. Virology 265:178-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belnap, D. M., B. M. McDermott, Jr., D. J. Filman, N. Cheng, B. L. Trus, H. J. Zuccola, V. R. Racaniello, J. M. Hogle, and A. C. Steven. 2000. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus receptor bound to poliovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:73-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomqvist, S., C. Savolainen, P. Laine, P. Hirttio, E. Lamminsalo, E. Penttila, S. Joks, M. Roivainen, and T. Hovi. 2004. Characterization of a highly evolved vaccine-derived poliovirus type 3 isolated from sewage in Estonia. J. Virol. 78:4876-4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouchard, M. J., D. H. Lam, and V. R. Racaniello. 1995. Determinants of attenuation and temperature sensitivity in the type 1 poliovirus Sabin vaccine. J. Virol. 69:4972-4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttinelli, G., V. Donati, S. Fiore, J. Marturano, A. Plebani, P. Balestri, A. R. Soresina, R. Vivarelli, F. Delpeyroux, J. Martin, and L. Fiore. 2003. Nucleotide variation in Sabin type 2 poliovirus from an immunodeficient patient with poliomyelitis. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1215-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherkasova, E. A., E. A. Korotkova, M. L. Yakovenko, O. E. Ivanova, T. P. Eremeeva, K. M. Chumakov, and V. I. Agol. 2002. Long-term circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus that causes paralytic disease. J. Virol. 76:6791-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fricks, C. E., J. P. Icenogle, and J. M. Hogle. 1985. Trypsin sensitivity of the Sabin strain of type 1 poliovirus: cleavage sites in virions and related particles. J. Virol. 54:856-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavrilin, G. V., E. A. Cherkasova, G. Y. Lipskaya, O. M. Kew, and V. I. Agol. 2000. Evolution of circulating wild poliovirus and of vaccine-derived poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient: a unifying model. J. Virol. 74:7381-7390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgescu, M. M., J. Balanant, A. Macadam, D. Otelea, M. Combiescu, A. A. Combiescu, R. Crainic, and F. Delpeyroux. 1997. Evolution of the Sabin type 1 poliovirus in humans: characterization of strains isolated from patients with vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis. J. Virol. 71:7758-7768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halsey, N. A., J. Pinto, F. Espinosa-Rosales, M. A. Faure-Fontenla, E. da Silva, A. J. Khan, A. D. B. Webster, P. Minor, G. Dunn, E. Asturias, H. Hussain, M. A. Pallansch, O. M. Kew, J. Winkelstein, R. Sutter et al. 2004. Search for poliovirus carriers among people with primary immune deficiency diseases in the United States, Mexico, Brazil and the United Kingdom. Bull. W. H. O. 82:3-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara, M., Y. Saito, T. Komatsu, H. Kodama, W. Abo, S. Chiba, and T. Nakao. 1981. Antigenic analysis of polioviruses isolated from a child with agammaglobulinemia and paralytic poliomyelitis after Sabin vaccine administration. Microbiol. Immunol. 25:905-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, Y., V. D. Bowman, S. Mueller, C. M. Bator, J. Bella, X. Peng, T. S. Baker, E. Wimmer, R. J. Kuhn, and M. G. Rossmann. 2000. Interaction of the poliovirus receptor with poliovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:79-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogle, J. M., M. Chow, and D. J. Filman. 1985. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 A resolution. Science 229:1358-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hovi, T., N. Lindholm, C. Savolainen, M. Stenvik, and C. Burns. 2004. Evolution of wild-type 1 poliovirus in two healthy siblings excreting the virus over a period of 6 months. J. Gen. Virol. 85:369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawamura, N., M. Kohara, S. Abe, T. Komatsu, K. Tago, M. Arita, and A. Nomoto. 1989. Determinants in the 5′ noncoding region of poliovirus Sabin 1 RNA that influence the attenuation phenotype. J. Virol. 63:1302-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kew, O., V. Morris-Glasgow, M. Landaverde, C. Burns, J. Shaw, Z. Garib, J. Andre, E. Blackman, C. J. Freeman, J. Jorba, R. Sutter, G. Tambini, L. Venczel, C. Pedreira, F. Laender, H. Shimizu, T. Yoneyama, T. Miyamura, H. van Der Avoort, M. S. Oberste, D. Kilpatrick, S. Cochi, M. Pallansch, and C. deq Uadros. 2002. Outbreak of poliomyelitis in Hispaniola associated with circulating type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus. Science 14:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kew, O. M., P. F. Wright, V. I. Agol, F. Delpeyroux, H. Shimizu, N. Nathanson, and M. A. Pallansch. 2004. Circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses: current state of knowledge. Bull. W. H. O. 82:16-23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kew, O. M., M. N. Mulders, G. Y. Lipskaya, E. E. da Silva, and M. A. Pallansch. 1995. Molecular epidemiology of polioviruses. Semin. Virol. 6:401-414. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kew, O. M., R. W. Sutter, B. K. Nottay, M. J. McDonough, D. R. Prevots, L. Quick, and M. A. Pallansch. 1998. Prolonged replication of a type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2893-2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koike, S., C. Taya, J. Aoki, Y. Matsuda, I. Ise, H. Takeda, T. Matsuzaki, H. Amanuma, H. Yonekawa, and A. Nomoto. 1994. Characterization of three different transgenic mouse lines that carry human poliovirus receptor gene—influence of the transgene expression on pathogenesis. Arch. Virol. 139:351-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korotkova, E. A., R. Park, E. A. Cherkasova, G. Y. Lipskaya, K. M. Chumakov, E. V. Feldman, O. M. Kew, and V. I. Agol. 2003. Retrospective analysis of a local cessation of vaccination against poliomyelitis: a possible scenario for the future. J. Virol. 77:12460-12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, J., L. B. Zhang, T. Yoneyama, H. Yoshida, H. Shimizu, K. Yoshii, M. Hara, T. Nomura, H. Yoshikura, T. Miyamura, and A. Hagiwara. 1996. Genetic basis of the neurovirulence of type 1 polioviruses isolated from vaccine-associated paralytic patients. Arch. Virol. 141:1047-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacCallum, F. O. 1971. Hypogammaglobulinaemia in the United Kingdom. VII. The role of humoral antibodies in protection against and recovery from bacterial and virus infections in hypogammaglobulinaemia. Spec. Rep. Ser. Med. Res. Counc. (G. B.) 310:72-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLennan, C., G. Dunn, A. P. Huissoon, D. S. Kumararatne, J. Martin, P. O'Leary, R. A. Thompson, H. Osman, P. Wood, P. Minor, D. J. Wood, and D. Pillay. 2004. Failure to clear persistent vaccine-derived neurovirulent poliovirus infection in an immunodeficient man. Lancet 363:1509-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin, J., G. Dunn, R. Hull, V. Patel, and P. D. Minor. 2000. Evolution of the Sabin strain of type 3 poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient during the entire 637-day period of virus excretion. J. Virol. 74:3001-3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGoldrick, A., A. J. Macadam, G. Dunn, A. Rowe, J. Burlison, P. D. Minor, J. Meredith, D. J. Evans, and J. W. Almond. 1995. Role of mutations G-480 and C-6203 in the attenuation phenotype of Sabin type 1 poliovirus. J. Virol. 69:7601-7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minor, P. 2001. Characteristics of poliovirus strains from long-term excretors with primary immunodeficiencies. Dev. Biol. (Basel) 105:75-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minor, P. D. 1990. Antigenic structure of picornaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 161:121-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minor, P. D. 1980. Comparative biochemical studies of type 3 poliovirus. J. Virol. 34:73-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minor, P. D., and G. Dunn. 1988. The effect of sequences in the 5′ non-coding region on the replication of polioviruses in the human gut. J. Gen. Virol. 69:1091-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minor, P. D., A. John, M. Ferguson, and J. P. Icenogle. 1986. Antigenic and molecular evolution of the vaccine strain of type 3 poliovirus during the period of excretion by a primary vaccinee. J. Gen. Virol. 67:693-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosser, A. G., J.-Y. Sgro, and R. R. Rueckert. 1994. Distribution of drug resistance mutations in type 3 poliovirus identifies three regions involved in uncoating functions. J. Virol. 68:8193-8201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omata, T., M. Kohara, S. Kuge, T. Komatsu, S. Abe, B. L. Semler, A. Kameda, H. Itoh, M. Arita, E. Wimmer, and A. Nomoto. 1986. Genetic analysis of the attenuation phenotype of poliovirus type 1. J. Virol. 58:348-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rousset, D., M. Rakoto-Andrianarivelo, R. Razafindratsimandresy, B. Randriamanalina, S. Guillot, J. Balanant, P. Mauclere, and F. Delpeyroux. 2003. Recombinant vaccine-derived poliovirus in Madagascar. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:885-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savilahti, E., T. Klemola, B. Carlsson, L. Mellander, M. Stenvik, and T. Hovi. 1988. Inadequacy of mucosal IgM antibodies in selective IgA deficiency: excretion of attenuated polio viruses is prolonged. J. Clin. Immunol. 8:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.Sayle, R. A., and E. J. Milner-White. 1995. RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skinner, M. A., V. R. Racaniello, G. Dunn, J. Cooper, P. D. Minor, and J. W. Almond. 1989. New model for the secondary structure of the 5′ non-coding RNA of poliovirus is supported by biochemical and genetic data that also show that RNA secondary structure is important in neurovirulence. J. Mol. Biol. 207:379-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tardy-Panit, M., B. Blondel, A. Martin, F. Tekaia, F. Horaud, and F. Delpeyroux. 1993. A mutation in the RNA polymerase of poliovirus type 1 contributes to attenuation in mice. J. Virol. 67:4630-4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Avoort, H. G. A. M., B. P. Hull, T. Hovi, M. A. Pallansch, O. M. Kew, R. Crainic, D. J. Wood, M. N. Mulders, and A. M. van Loon. 1995. Comparative study of five methods for intratypic differentiation of polioviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2562-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood, D. J., R. W. Sutter, and W. R. Dowdle. 2000. Stopping poliovirus vaccination after eradication: issues and challenges. Bull. W. H. O. 78:347-357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization. 2004. Manual for the virological investigation of poliomyelitis. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 44.Yang, C.-F., T. Naguib, S.-J. Yang, E. Nasr, J. Jorba, N. Ahmed, R. Campagnoli, H. van der Avoort, H. Shimizu, T. Yoneyama, T. Miyamura, M. Pallansch, and O. Kew. 2003. Circulation of endemic type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus in Egypt from 1983 to 1993. J. Virol. 77:8366-8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]