Abstract

Infection by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) induces a persistent nuclear translocation of NFκB. To identify upstream effectors of NFκB and their effect on virus replication, we employed mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF)-derived cell lines with deletions of either IKK1 or IKK2, the catalytic subunits of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Infected MEFs were assayed for virus yield, loss of IκBα, nuclear translocation of p65, and NFκB DNA-binding activity. Absence of either IKK1 or IKK2 resulted in an 86 to 94% loss of virus yield compared to that of normal MEFs, little or no loss of IκBα, and greatly reduced NFκB nuclear translocation. Consistent with reduced virus yield, accumulation of the late proteins VP16 and gC was severely depressed. Infection of normal MEFs, Hep2, or A549 cells with an adenovirus vector expressing a dominant-negative (DN) IκBα, followed by superinfection with HSV, resulted in a 98% drop in virus yield. These results indicate that the IKK-IκB-p65 pathway activates NFκB after virus infection. Analysis of NFκB activation and virus replication in control and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-null MEFs indicated that this kinase plays no role in the NFκB activation pathway. Finally, in cells where NFκB was blocked because of DNIκB expression, HSV failed to suppress two markers of apoptosis, cell surface Annexin V staining and PARP cleavage. These results support a model in which activation of NFκB promotes efficient replication by HSV, at least in part by suppressing a host innate response to virus infection.

Cells activate the transcription factor NFκB in a wide variety of situations, including responses to stress-inducing insults such as UV irradiation and virus infection or in response to cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). NFκB has an important role in suppression of apoptosis and regulates the expression of many important antiapoptotic functions (5, 31, 48, 50). NFκB, as a p65/p50 heterodimer, is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm in a complex with inhibitor of κB (IκB). IκBα is targeted for phosphorylation at serine residues 32 and 36, and IκBβ is targeted for phosphorylation at serine residues 19 and 23 (42, 46, 51), by the multisubunit IκB kinase (IKK) (11, 23, 36, 52, 58). This phosphorylation triggers its polyubiquitylation and destruction by the 26S proteosome (6, 7, 12), and, as a result, NFκB is translocated to the nucleus (14, 57). Key roles for IKK and IκB in NFκB signaling were demonstrated in studies in which overexpression of a kinase-dead, trans-dominant form of IKK prevents IκB phosphorylation and inhibits NFκB activation (36, 52). IKK is activated by phosphorylation mediated by mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase kinases (MAP3Ks) MEKK1, -2, or -3 or NFκB-inducing kinase (NIK) (23, 30, 37, 59). Under stress conditions, the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) has been shown to activate NFκB through a pathway dependent on NIK and IKK (57). Distinct roles for the catalytic components of the IKK have been recognized. IKKα appears to play a major role in transducing signals for NFκB activation during embryonic development (18, 45), while IKKβ is essential for cytokine and other stress-induced signaling pathways (10, 27, 29). Besides cytoplasmic roles in the activation of NFκB, recent studies have identified IKKα and the IKK scaffold protein IKKγ/NEMO in direct regulation of NFκB-dependent transcription in the nucleus (2, 49, 53). NFκB activation is also dependent on distinct signaling pathways which target p65 for phosphorylation (32).

The ability of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) to activate NFκB has been well documented (1, 15, 40). Beginning at 3 to 5 h postinfection (hpi), HSV-1 induced a strong and persistent nuclear translocation, increased p50/p65-dependent DNA binding activity as measured by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), and induced activation of a 3XNFκB-luciferase reporter. Persistent NFκB activation required virus binding and entry as well as de novo infected cell protein synthesis, including expression of functional viral immediate-early (IE) protein ICP27. Activation was also accompanied by increased IKK activity and loss of both IκBα and IκBβ. Interference with NFκB activation occurred following expression of a dominant-negative IκBα (DNIκB) containing alanine substitutions for serine residues 32 and 36 normally targeted by IKK. The resulting substantial reduction in NFκB EMSA activity correlated with a reduction in virus yield. The latter may be related to the reported role of NFκB in preventing HSV-1-induced apoptosis (15). The foregoing results argue that the observed persistent NFκB activation, rather than being a host response to virus infection, plays a positive role in the promoting efficient virus replication.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and associated downstream signaling components can also mediate activation of NFκB (35, 44). While HSV-1 infection stimulated interferon production in mice by a mechanism dependent on TLR9/MyD88 (20) and TLR2 mediated an inflammatory response that contributes to lethal encephalitis in a murine model of HSV-1 pathogenesis (22), as yet no direct evidence links TLRs to NFκB activation during HSV-1 infection.

The experiments presented here were designed to more fully characterize the activation pathway for NFκB in HSV-infected cells and to assess how components of the classical NFκB activation pathway (IKKβ-IκBα-p65/p50) contribute to virus replication. Our approach was to assess virus replication and markers of NFκB activation in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) with targeted deletions in key components of the signaling pathway (IKKα or IKKβ) or through overexpression of a DNIκBα and to assess HSV replication and the ability of HSV to suppress markers of apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

All experiments were performed with the KOS1.1 strain of HSV-1. Adenovirus vectors expressing a dominant-negative IκBα (DNIκBα) or green fluorescent protein (GFP) were obtained from the Virus Vector Core Facility at University of North Carolina (UNC)-Chapel Hill. Spontaneously immortalized mouse embryo fibroblasts derived from normal mice or mice with targeted deletions in IKKα or IKKβ (26, 27) were obtained form Tal Kafri (UNC-Chapel Hill). MEFs from normal mice or mice with a targeted deletion of the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR (54) were obtained from Bryan Williams (Cleveland Clinic). These cell lines as well as A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine calf serum, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 1% streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine (all from Gibco). Hep2 cells were maintained in minimal essential medium supplemented as described for DMEM.

Plaque assay.

Monolayers of cells in 60-mm-diameter dishes were infected with HSV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5, and cells and medium were harvested at various times postinfection, followed by three cycles of freezing and thawing. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the lysates were assayed in triplicate on monolayers of Vero cells in 12-well dishes. After 1 h, monolayers were covered with DMEM-H containing 2% calf serum and 0.3% methylcellulose. After 3 days of incubation at 37°C, medium was aspirated from the wells and plaques were stained with 0.8% crystal violet in 50% ethanol (EtOH).

Preparation of cell extracts and Western blotting.

For preparation of whole-cell extracts, medium was removed and monolayers were rinsed with ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were scraped directly into 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (3.85 mM Tris base [(pH 6.8], 9.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1.82% SDS, 4.6% glycerol, and 0.023% bromophenol blue [in 100% EtOH]) and denatured by boiling. Cell-equivalent amounts of lysate were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Fractionated cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (38). Briefly, cells were collected by trypsinization, spun through a cushion of bovine calf serum, washed twice in PBS, resuspended in three packed cell volumes (PCV) of CE buffer (10 mM HEPES, [pH 7.8], 1 mM EDTA, 60 mM KCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 0.1% NP-40, 25% glycerol, 0.4 mM NaF, 0.4 mM Na3VO4, 10 μM pepstatin, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail [Roche]), and incubated on ice for 10 min. Following a 10-s spin in a benchtop microcentrifuge, the supernatant was removed and the nuclear pellet was resuspended in CW buffer (CE buffer without NP-40 or glycerol) and repelleted. Nuclei were resuspended in 2 PCV of NE buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 25% glycerol, and phosphatase and protease inhibitors as described above). After incubation on ice for 10 min, nuclei were pelleted at 60,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min in a Beckman TLA100.3 rotor. The nuclear extract supernatant was carefully removed, and aliquots were stored at −80°C.

Equal amounts of protein were transferred to PolyScreen polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences) followed by blocking in TBST (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 0.05% Tween 20) with 5% milk. All probing and washing of membranes was done in TBST. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies for IKKβ (H-470, sc-7607), IKKα (H-744, sc-7218), and IκB-α (C-21, sc-371) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology were used at a 1:1,000 dilution overnight at 4°C per the manufacturer's instructions. Rabbit polyclonal antibody for p65 (100-4165) was from Rockland and was used at a 1:2,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Monoclonal antibodies against HSV IE ICP4 (1101) and ICP27 (1119) were purchased from the Rumbaugh-Goodwin Institute for Cancer Research (Plantation, Fla.) and were used at a 1:800 dilution. Polyclonal antibody for VP16 (Clontech) was used at a 1:5,000 dilution. Polyclonal antibody against ICP8 (3-83) was a generous gift from David Knipe (Harvard University) and was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Polyclonal antibody against gC (R47), used at 1:5,000, was a generous gift of Gary Cohen (University of Pennsylvania). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to PARP (H-250, sc-7150) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. The secondary antibody was detected with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate agent (Pierce). Autoradiographic films were scanned, and images were stored as 8-bit grayscale JPEG files. The density of each band was determined by using Image J (National Institutes of Health). Relative density values were corrected for average background by subtracting the density of a blank portion of the film. The corrected values were then used to calculate fold change relative to the control sample (e.g., the ratio of the mock-infected cell value to the infected cell value).

EMSA.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and mobility shift assays for NFκB were performed as described previously (17, 38, 40). Nuclear extract was incubated with a radiolabeled probe containing a κB-binding site, TGGGGATTCCCCA, in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 μg of poly(dI-dC) · poly(dI-dC). Following 20 min of incubation at room temperature, aliquots were fractionated at 4°C on nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels prepared in 0.25× TBE (1× TBE is 10 mM Tris base [pH 8.3], 9 mM boric acid, and 2 mM EDTA). Gels were then placed on 3MM paper, dried under vacuum and heat, and exposed to Kodak BMR film at −70°C.

Annexin V staining.

Infected Hep2 cells were stained with Annexin V by using the Vybrant Apoptosis Assay kit #2 (Molecular Probes) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were harvest by trypsin treatment and were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine calf serum, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 1% streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine. Following pelleting, cells were resuspended at 106/ml in 1× binding buffer followed by addition of 50 μl of Annexin stain/ml and 10 μl of propidium iodide (100 μg/ml in 1× binding buffer)/ml. Cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and then 400 μl of binding buffer was added for a total volume of 500 μl. Stained cells were kept on ice until Annexin staining was quantified by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

RESULTS

Both IKKα and IKKβ contribute to virus yield and NFκB activation in HSV-infected cells.

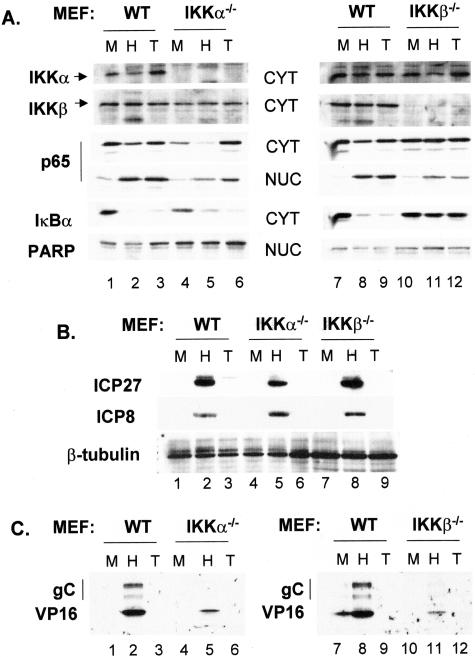

The multisubunit IKK complex phosphorylates IκB, triggering the latter's destruction and subsequent nuclear localization of NFκB (14, 57). IKK activity was reported to increase following HSV infection (1). To determine the importance of IKK catalytic subunits IKKα and IKKβ on the replication efficiency of HSV-1, we prepared lysates at 8 hpi from cell lines derived from normal MEFs or MEFs from embryos with targeted deletions of either IKKα or IKKβ and assessed the effect of loss of either catalytic component of IKK on levels of IκBα and nuclear translocation of p65, two markers of NFκB activation. The results of Western blots are presented in Fig. 1A. First, cytoplasmic extracts were probed for IKK subunits to confirm their presence or absence in IKKa−/− and IKKb−/− MEF lines (compare IKKα and IKKβ in lanes 1 to 3 with 4 to 6 and lanes 7 to 9 with 10 to 12). IKKα and IKKβ levels were used as loading controls for cytoplasmic samples, and PARP was used as a loading control for nuclear samples. As an assessment of our fractionation procedure, we did not detect IKKα or IKKβ in nuclear lysates or PARP in the cytoplasm (data not shown). Following infection or TNF-α treatment of wild-type (WT), IKKa−/−, and IKKb−/− cells, we observed nuclear translocation of p65 (compare lanes 1 to 6 and 7 to 12). Compared to their corresponding mock-infected nuclear samples, increases in nuclear p65 following HSV infection or TNF-α treatment were approximately twofold greater in WT cells than in either of the IKK knockout cell types. Importantly, infection of WT and IKKa−/− cells also resulted in two- to threefold reductions in cytoplasmic p65 compared to that of mock-infected cells, while no reduction in cytoplasmic p65 was detected in IKKb−/− cells following infection or TNF-α treatment. We observed an apparent increase in the total amount of p65 after TNF-α treatment of both WT and IKKa−/− cells (lanes 3 and 6). Whether this reflects the ability of this cytokine to activate Sp1 and transcriptionally activate the p65 promoter (47) is presently unknown. Quantification by Image J, as described in Materials and Methods, revealed 29- and 20-fold reductions, respectively, in IκBα following HSV infection or TNF-α treatment of WT cells. Reductions of IκBα in IKKa−/− cells were 4.4-fold following HSV infection and 8.7-fold after TNF-α treatment. Consistent with the reduced nuclear translocation of p65 observed in IKKb−/− cells, IκBα was reduced in these cells only 1.3- and 1.1-fold following infection or TNF-α treatment.

FIG. 1.

Both IKKα and IKKβ contribute to the activation of NFκB in HSV-infected cells. Western blot analysis for proteins involved in NFκB activation (A) and for viral proteins (B and C) in murine cell lines. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from normal (WT), IKKa−/−, IKKb−/−, p65−/−, and p65+/+ cells at 8 hpi, and they were then probed for the indicated cellular and viral proteins as described in Materials and Methods. M, mock infected; H, HSV infected; T, TNF-α treated. (B) Nuclear extracts were probed for ICP27 and ICP8, while cytoplasmic extracts were probed for gC and VP16.

Filters were also probed for several viral proteins representative of different kinetic classes. While IE ICP27 levels were comparable between WT and IKKb−/−, we observed decreased ICP27 accumulation (1.7-fold relative to that of the WT) in IKKa−/− cells. Delayed early (DE) ICP8 accumulation was comparable in the three cell types (Fig. 1B, lanes 2, 5, and 8). In contrast, accumulation of the L proteins VP16 and gC was considerably reduced in both knockout cell lines (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 and 5 and lanes 8 and 11). Here we observed decreases in VP16 of 5- to 6-fold and decreases in gC of 6- to 10-fold, respectively, in IKKa−/− and IKKb−/− lysates compared to those of WT.

Next, we determined virus yields in cell lines derived from normal MEFs compared to those of IKKa−/− and IKKb−/− MEFs. Cultures were harvested at 16 and 24 hpi, and infectious virus was titered on Vero cell monolayers. Results, presented in Table 1, indicated that both IKKα- and IKKβ-deficient cells were impaired in supporting virus replication, because virus yield at 24 h was reduced 6- to 28-fold compared to that of normal cells. Taken together, the results of yield assays in Table 1 are consistent with results of Western blots indicating that both IKKa−/− and IKKb−/− cells were impaired in nuclear translocation of p65 and in aspects of late viral protein accumulation.

TABLE 1.

Virus yield assays from normal, IKKα−/−, and IKKβ−/− MEFsa

| Cell type | Results at 16 hpi

|

Results at 24 hpi

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | |

| Normal | (3.86 ± 1.5) × 107 | (3.74 ± 0.36) × 107 | ||

| IKKα−/− | (7.09 ± 3.4) × 106 | 5.4 | (6.0 ± .37) × 106 | 6.2 |

| IKKβ−/− | (2.4 ± 0.16) × 106 | 16.3 | (2.62 ± 0.33) × 106 | 28.5 |

Cells and culture media from three independent experiments were collected at the indicated times postinfection, and yields were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Relative fold decrease is the ratio of yield on control cells to knockout cells.

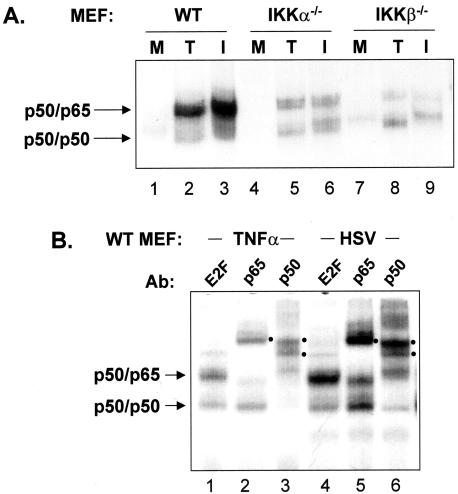

We also prepared nuclear extracts from mock-infected, TNF-α-treated, and HSV-infected cells and performed EMSA to determine the effect of loss of IKKα or IKKβ on NFκB DNA-binding activity. In these cell lines we could detect an abundant NFκB complex consisting of p50/p65 under conditions of TNF-α treatment or HSV-1 infection (Fig. 2B). Thus, incubation of lysates with a p65 antibody supershifted a relatively low-mobility complex, while an incubation with a p50 antibody supershifted both the relatively low-mobility complex and a higher mobility complex. Incubation with an irrelevant antibody to E2F served as a control. While the ability of p65 and p50 antibodies to shift complexes from TNF-α-treated cells appeared quantitative, a small amount of unshifted p50/p65 and p50/p50 complexes persisted following incubation of lysates from infected cells with p65 and p50 antibodies. The precise nature of these complexes is presently unknown. The results presented in Fig. 2A indicate that the absence of either of the IKK catalytic subunits resulted in decreased levels of nuclear NFκB (p50/p65), consistent with their role in nuclear translocation of p50/p65. Interestingly, the amounts of p50 homodimer activity increased in all three cell types following HSV infection or TNF-α treatment (see Fig. 2B for a better example of p50 homodimer activity in WT cells). This latter result suggests that the SCF(β)-TrCP ubiquitin ligase required to initiate limited proteolysis of p105 to yield p50 is activated following both TNF-α treatment and HSV-1 infection (39).

FIG. 2.

IKKα and IKKβ contribute to NFκB activation and efficient replication in HSV-infected cells. (A) EMSA for NFκB DNA-binding activity in WT, IKKa−/−, and IKKb−/− MEFs was performed with extracts prepared from mock-infected cells (M), cells infected for 8 h with HSV (I), or cells treated for 15 min with TNF-α (T). (B) Extracts prepared from WT MEFs treated for 15 min with TNF-α or infected for 8 h with HSV were incubated with antibody to NFκB subunits p50 or p65 or an irrelevant antibody against E2F4 prior to incubation with the NFκB-specific oligonucleotide. Filled circles to the right of each lane identify supershifted complexes in response to incubation with anti-p50 or anti-p65. For both panels, only the portion of the autoradiograph containing specific complexes is shown.

IκBα contributes to efficient replication of HSV.

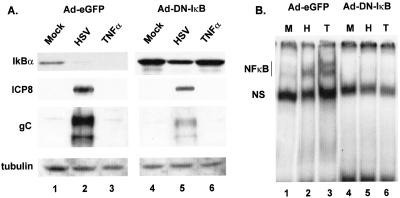

NFκB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by IκB. Following phosphorylation of IκBα at serine residues 32 and 36, which triggers its polyubiquitylation and destruction by the 26S proteosome, NFκB translocates into the nucleus. DNIκB, in which these serines are mutated to alanines, is resistant to cytokine-induced turnover, and p50/p65 is retained in the cytoplasm (42). It was previously reported that infection of pooled clones of C33-A cells stably expressing DNIκB resulted in reduced nuclear translocation of NFκB and reduced virus yield compared to that of control cells (40). This experimental approach could not control for variable expression of DNIκB among individual cells and could potentially accommodate some NFκB activation and virus replication. We therefore employed infection with an adenovirus vector to transiently express DNIκB in all cells in the culture. A549 cells were infected with an adenovirus vector expressing GFP (Ad-eGFP) or with adenovirus expressing DNIκB (Ad-DNIκB), and after 16 h the cells were superinfected with HSV for 8 h or were treated with TNF-α for 15 min prior to harvest. Figure 3A represents Western blots for IκBα in cytoplasmic extracts. Infection with HSV or treatment with TNF-α of cells infected with Ad-eGFP resulted in the almost complete loss of endogenous IκBα (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 3). A 1.45-fold decrease in IκBα was detected in cells infected with Ad-DNIκB and superinfected with HSV, consistent with loss of only the endogenous form of the protein. The total level of IκBα present following TNF-α treatment was unchanged compared to that of mock treatment (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 4 and 6). Whether this reflected minimal loss of endogenous IκBα following treatment is unclear, but analysis of nuclear extracts by EMSA (Fig. 3B.) indicated efficient suppression of NFκB DNA-binding activity in cells infected with Ad-DNIκB (compare lanes 1 to 3 with lanes 4 to 6). The effect of DNIκB on viral gene expression was also analyzed. Lysates from control and DNIκB lysates were probed for the DE protein ICP8 and the L protein gC and were quantified by Image J. While there was a twofold decrease in the amount of ICP8, the level of gC declined 6.5-fold in DNIκB-expressing cells compared to that in the control lysate. These results were reminiscent of those presented in Fig. 1 for the effect on viral protein accumulation in cells lacking IKKα or IKKβ.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of cells expressing DNIκB. (A) Western blot for IκBα and viral proteins. Replicate cultures of A549 cells were infected with a 100-ffu/cell concentration of adenovirus vector expressing enhanced GFP (Ad-eGFP) or DNIκBα (Ad-DNIκB). After 16 h, monolayers were mock infected (lanes 1 and 4), infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 5 for 8 h (lanes 2 and 5), or treated with 50 ng of human recombinant TNF-α/ml (lanes 3 and 6) for 15 min prior to harvest. Cytoplasmic lysates were prepared and analyzed for IκBα, gC, or α-tubulin by Western blot. Nuclear lysates were analyzed for ICP8. (B) EMSA for NFκB binding activity. Nuclear lysates were prepared from A549 cells initially infected with either Ad-eGFP or Ad-DNIκB, and then they were either mock infected, infected with HSV-1, or treated with TNF-α as described for cultures analyzed in the experiment presented in panel A. NS, nonspecific binding activity.

We then determined the effect of DNIκB expression on virus replication following a similar infection protocol. We infected murine 3T3 cells and the human tumor cell lines A549 and Hep2 with Ad-DNIκB, followed by HSV superinfection. Production of progeny virus was determined by a plaque assay on Vero cells, and the results are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Two separate experiments involving murine fibroblasts were performed. Infectious virus was assayed at 16 and 24 hpi following low-MOI (0.2) infection or at 20 hpi following infection at an MOI of 0.2 or 1. Virus yields were reduced ∼15- to 25-fold in DNIκB-expressing cells compared to that of Ad-eGFP control cells (Table 2). Following low-MOI (0.2) infection of A549 or Hep2 cells, virus yield was reduced to 1,300-fold (Table 3). When the input MOI of A549 cells was increased to 1, the fold decrease in virus yield was reduced accordingly (42- to 62-fold) and still represented a significant decrease of 18-fold even at an MOI of 5. Replication of HSV in Hep2 cells was extremely sensitive to expression of DNIκB. Even at an MOI of 5, virus yield was reduced almost 800-fold (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Virus yield in WT MEFsa

| Expression vector and expt no. | Results at 16 hpi

|

Results at 20 hpi

|

Results at 24 hpi

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | |

| Expt 1 | ||||||

| Ad-eGFP (HSV MOI = 0.2) | 1.4 × 107 | 2.5 × 107 | ||||

| Ad-DNIκB (HSV MOI = 0.2) | 2.3 × 106 | 6 | 1.7 × 106 | 14.7 | ||

| Expt 2 | ||||||

| Ad-eGFP (HSV MOI = 0.2) | 1.95 × 107 | |||||

| Ad-DNIκB (HSV MOI = 0.2) | 7.4 × 105 | 26.4 | ||||

| Ad-eGFP (HSV MOI = 0.1) | 3.7 × 107 | |||||

| Ad-DNIκB (HSV MOI = 0.1) | 2.23 × 106 | 16.6 | ||||

Cells and culture media were collected at the indicated time points, and infectious titers were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Relative fold increase in virus yield is the ratio of yield from control cultures to yield from DNIκB-expressing cultures.

TABLE 3.

Virus yield in A549 and Hep2 cells expressing DNIκBa

| Cell type, expression vector, and expt no. | Results at HSV MOI of 0.2

|

Results at HSV MOI of 1.0

|

Results at HSV MOI of 5.0

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | |

| A549 | ||||||

| Expt 1 | ||||||

| Ad-eGFP | 4.1 × 108 | 4.1 × 108 | 4.5 × 108 | |||

| Ad-DN-IκB | 4.1 × 106 | 100 | 9.8 × 106 | 41.8 | 2.4 × 107 | 18.4 |

| Expt 2 | ||||||

| Ad-eGFP | 5.7 × 107 | 8.7 × 107 | 1.05 × 108 | |||

| Ad-DN-IκB | 2.13 × 105 | 267 | 1.41 × 106 | 61.7 | 5.6 × 106 | 18.7 |

| Hep2 | ||||||

| Expt 1 | ||||||

| Ad-eGFP | 1.3 × 107 | 7.8 × 107 | 1.5 × 108 | |||

| Ad-DN-IκB | 1 × 104 | 1,300 | 6.7 × 104 | 1,164 | 1.9 × 105 | 789 |

Cells and culture medium were collected, and infectious titers were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Cultures were harvested at 24 hpi. Relative fold decrease in virus yield is the ratio of yield from control cultures to yield from DN-IκB expressing cultures. The analysis of virus yield in Hep2 cells was performed once.

PKR is not necessary for NFκB activation in HSV-infected cells.

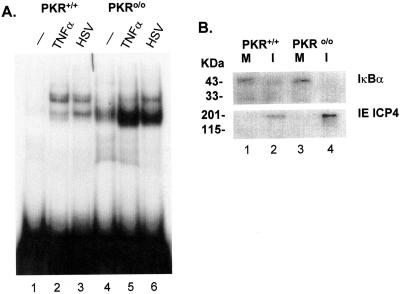

Because HSV induces IKK activity (1) and because IKKα and IKKβ both contribute to NFκB activation by HSV-1 (Fig. 1 and 2), we next asked whether PKR, a stress- and virus-induced kinase, is necessary for NFκB activation and efficient virus replication. The double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase, PKR, activates NFκB by stimulating IKK activity and inducing turnover of IκBα and IκBβ (57), though it is not known whether the critical serine residues on IκBα and IκBβ are phosphorylated (21, 33). In fibroblasts from PKR-deficient (PKR0/0) mouse embryos, double-stranded RNA, alpha interferon, and gamma interferon failed to activate NFκB, while TNF-α still functioned as an inducer (57). PKR is known to be activated with late kinetics in cells infected with WT HSV-1 and γ1 34.5 mutants of HSV-1, but it is not known whether this is via autophosphorylation or by a virus-encoded or -induced kinase (8). PKR-dependent phosphorylation of eIF2α is reversed in virus-infected cells through the action of the γ1 34.5 protein (16). Recently, NFκB activation in HSV-infected cells was reported to be dependent on PKR, based on infection of PKR+/+ and PKR0/0 MEFs (43). MEFs from normal mice (PKR+/+) or mice with a targeted deletion of PKR (PKRο/ο) (54) were infected with HSV, and virus yields at 16 and 24 hpi were determined by plaque assay (Table 4). Virus yields from PKRο○/ο○ cells were similar at 16 h and were approximately fourfold increased at 24 h relative to yields from PKR+/+ cells. EMSA for NFκB DNA-binding activity from nuclear extracts of PKR+/+ and PKRο/ο cells are presented in Fig. 4A. Little NFκB activity was detectable in the extract from mock-infected PKR+/+ cells, while both TNF-α treatment and HSV infection induced NFκB activities consisting of p50/p65 or operationally defined as p50 homodimer, based on effects of p65 and p50 antibodies on the mobility of the complexes (data not shown). Mock-infected PKRο/ο cells constitutively expressed the p50 activity, which increased substantially following HSV infection or TNF-α treatment. HSV infection also induced p50/p65 activity comparable to that seen in the PKR+/+ cells, while TNF-α induction was impaired. Finally, we asked whether the absence of PKR affected the turnover of IκBα normally observed after virus infection. Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed by Western blot (Fig. 4B). Amounts of IκBα were considerably reduced after HSV infection of both PKR+/+ and PKRο/ο cells, while the amount of ICP4 detected was greater in the PKRο/ο lysate. Together, these results indicate that PKR is not essential for HSV-induced NFκB activation, but it does contribute to NFκB activation by TNF-α. It remains possible that PKR can have offsetting effects on virus replication. For example, PKR may contribute to NFκB activation when present, but in its absence the pathway leading to eIF2α phosphorylation is disrupted. At this time we cannot rule out the possibility that the greatly increased amount of p50 homodimer also contributes to efficient virus replication (see Discussion). The basis for the differences between our results and those previously published (43) is unclear, though they could reflect differences in HSV strain or the time of harvest postinfection.

TABLE 4.

Effect of loss of PKR on virus yielda

| Cell type | Results at 16 hpi

|

Results at 24 hpi

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold decrease | Yield (PFU/culture) | Fold increase | |

| PKR+/+ | 1.65 × 107 | 2.2 × 107 | ||

| PKR0/0 | 1.25 × 107 | 1.3 | 9.0 × 107 | 4 |

Monolayers of PKR+/+ and PKR0/0 cells were infected with HSV at an MOI of 5. Cells and culture media were collected at the indicated times postinfection, and infectious titers were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Virus yield on these cell types was analyzed once.

FIG. 4.

PKR is not necessary for NFκB activation in HSV-infected cells. (A) EMSA for NFκB was performed as described in Materials and Methods with nuclear extracts prepared from mock-infected, TNF-α-treated, or HSV-infected PKR+/+ and PKRο/ο MEFs. (B) Western blot of IκBα and IE ICP4 was performed on whole-cell extracts prepared from mock-infected (M) or HSV-infected (I) PKR+/+ and PKRο/ο MEFs.

NFκB promotes an antiapoptotic response in HSV-infected cells.

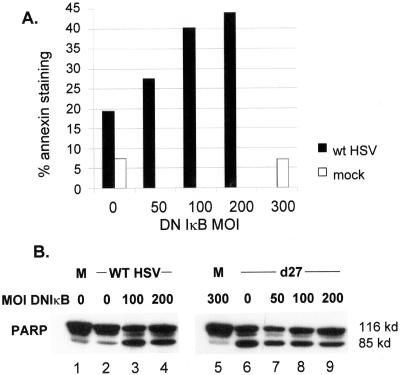

HSV efficiently suppresses apoptosis (3, 4, 19, 24, 25, 62), and one recent report pointed to activation of NFκB as an important mediator of this effect (15). NFκB has a well-documented role in suppressing apoptosis under a variety of conditions (5, 31, 48, 50). One way in which the NFκB activation pathway might be linked to enhanced virus yields would be through the mechanism of apoptosis suppression. To test this model we asked whether expression of DNIκB eliminated apoptosis suppression by HSV. We assayed for cell surface phosphoserine by staining with fluorochrome-conjugated Annexin V and for cleavage of PARP (Fig. 5). Parallel cultures of Hep2 cells were infected with Ad-DNIκB, followed at 16 h by superinfection with HSV. Uninfected cultures or cultures receiving Ad-DNIκB but not superinfected with HSV served as controls, and all cultures with HSV were harvested at 24 hpi. The fraction of HSV-infected cells stained with Annexin V increased from ∼20 to ∼43% by 24 hpi as the MOI of Ad-DNIκB increased from 0 to 200 focus-forming units (ffu)/cell (Fig. 5A). By contrast, only 7% of cells infected with 300 ffu of Ad-DNIκB but not superinfected with HSV displayed cell surface Annexin V staining. In a second experiment, we infected Hep2 cells with different amounts of Ad-DNIκB, followed by mock infection, infection with WT HSV-1, or infection with the ICP27 mutant d27-1. The latter virus has been reported to efficiently induce apoptosis in human cells (3, 4). Lysates were prepared and assayed for PARP by Western blot, and the results are shown in Fig. 5B. Whereas unprocessed (∼116 kDa) PARP was present in all lysates, increased amounts of processed PARP (85-kDa) were present in lysates of WT HSV-infected cells only when DNIκB was expressed (lanes 3 to 4) or in lysates from all cultures infected with d27-1 (lanes 6 to 9).

FIG. 5.

NFκB promotes an antiapoptotic response in HSV-infected cells. (A) Replicate monolayers of Hep2 cells were infected with an adenovirus vector expressing DNIκB from a cytomegalovirus promoter at the indicated MOI. After 24 h, monolayers were either mock infected or infected with HSV at an MOI of 5. At 24 hpi cells were harvested, stained for Annexin V, and processed for FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Parallel cultures of Hep2 cells were infected with adenovirus vector expressing DNIκB at the indicated MOIs. After 24 h, monolayers were mock infected or infected with WT HSV-1 or the ICP27 null mutant d27-1 at an MOI of 5. Whole-cell extracts were prepared at 24 hpi for Western blot analysis of PARP.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have described NFκB activation after HSV infection (1, 15, 40). Results of studies reported here extend this observation, documenting the roles of upstream effectors of NFκB in this process as well as in efficient virus replication. Specifically, IKKα and IKKβ as well as IκBα are critical for efficient activation, as measured by nuclear localization of p65 and increases in nuclear NFκB-dependent EMSA activity. Though activated after HSV infection, no role for PKR in NFκB activation was observed. As measured by either accumulation of specific viral proteins or production of infectious virus, the intact IKK-IκBα-NFκB pathway contributed to efficient virus replication. This efficiency of virus replication may in part reflect the suppression of apoptosis by a mechanism requiring activation of the NFκB. It was previously reported (40) that nuclear translocation of NFκB after HSV infection was not accompanied by NFκB-dependent promoter activation. Amici and coworkers (1) reported functional activation of NFκB after infection, and the work of Goodkin et al. (15) and work presented here imply that NFκB is functional and participates in the program of apoptosis suppression following virus infection. We attribute the previous inability to detect NFκB activity largely to the cell type (C33-A) and the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter used in previous studies. We can readily detect functional NFκB in HeLa and HEK293T cells following infection by using a 3XNFkB luciferase-based reporter (D. Hargett, J. Prince, and S. Bachenheimer, unpublished observations).

The requirement for IKK in NFκB activation during HSV infection of murine fibroblasts largely mirrors its requirement for activation by TNF-α. Thus, loss of cytoplasmic IκBα and nuclear accumulation of p65 were either modestly impaired (IKKa−/−) or largely impaired (IKKb−/−) relative to normal cells, and NFκB-dependent EMSA activity was greatly reduced. It has been reported that IKKβ plays a critical role (27, 29), while IKKα plays a redundant (18, 26, 45) or distinct (28, 41) role, in cytokine-mediated NFκB activation in murine cells. By using an RNA interference approach, both IKK catalytic subunits were shown to play critical roles in cytokine-induced NFκB in human cells (44). Future experiments will be directed at understanding whether a requirement for both IKKα and IKKβ also holds for NFκB activation by HSV in human cells. Both IKKa−/− and IKKb−/− cells supported comparable amounts of IE ICP27 and DE ICP8 accumulation relative to normal cells, but they had greatly reduced expression of L proteins VP16 and gC. These results are consistent with the reduced yield of infectious virus from these cell lines and with previous reports on virus yield (1, 40).

Infection of murine fibroblasts deleted for PKR resulted in NFκB-dependent EMSA activity and yield of infectious virus comparable to or greater than that seen following infection of normal cells. We also noted constitutive expression of a p50 homodimer form of NFκB and its substantial increase following either TNF-α treatment or HSV infection. While p50 homodimers would not be expected to have transcriptional transactivation potential, Bcl-3, an IκBα family member, complexes with and relocates p50 homodimers to the nucleus, where it can also serve as a transcriptional coactivator of p50 homodimers (9, 13). Thus, it remains possible that increased p50 homodimer formation in part mediates efficient HSV replication in PKR0/0 cells and that preventing p50/p65 activation by, for example, ectopic expression of DNIκB may not reduce HSV replication.

HSV infection induces and then efficiently suppresses apoptosis. Consistent with the role of NFκB as a cell survival factor, there is a strong correlation between the ability of HSV to express functional ICP27 and the suppression of apoptosis (3) and between expression of NFκB and suppression of apoptosis (15). Coupled with the requirement for functional ICP27 to activate NFκB (D. Hargett and S. Bachenheimer, submitted for publication), we propose that a delayed-type activation of NFκB, dependent on viral gene expression, plays an important role in prolonging functional cell survival and, thus, efficient virus replication. This delayed-type activation has also been observed following infection of cells with human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (55) and was termed second-tier activation. Another mechanism of virus-induced NFκB activation is inferred from experiments which characterized the ability of HSV-1 to both trigger and inhibit apoptosis (4, 25). A key finding in the recognition of a rapid-type activation of NFκB stemmed from experiments which demonstrated that ectopic expression of virion glycoproteins gD or gJ could rescue cells from apoptosis following infection with virus deleted for the gD gene (61, 62). Interestingly, the domains of gD involved in blocking apoptosis for the most part do not overlap those domains involved in binding HveC, the ubiquitously expressed gD receptor (60). More recently, either infection with UV-inactivated HSV or exposure of cells to gD was shown to protect cells from Fas-mediated apoptosis by a mechanism that was dependent on NFκB activation (34). One inference that could be drawn from both these experiments was that the protective effect of gD occurred at the time of virus binding and entry and, thus, did not have a requirement for de novo viral gene expression. This situation is similar to that of the first-tier activation of NFκB observed during infection with HCMV (56) and suggests that two mechanistically distinct mechanisms of NFκB activation occur during HSV infection.

Acknowledgments

D.G. was supported by NIH grant T32 GM-07092. This work was supported by NIH grant AI43314 to S.L.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amici, C., G. Belardo, A. Rossi, and M. G. Santoro. 2001. Activation of Iκb kinase by herpes simplex virus type 1. A novel target for anti-herpetic therapy. J. Biol. Chem. 276:28759-28766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anest, V., J. L. Hanson, P. C. Cogswell, K. A. Steinbrecher, B. D. Strahl, and A. S. Baldwin. 2003. A nucleosomal function for IκB kinase-alpha in NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Nature 423:659-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubert, M., and J. A. Blaho. 1999. The herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP27 is required for the prevention of apoptosis in infected human cells. J. Virol. 73:2803-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubert, M., S. A. Rice, and J. A. Blaho. 2001. Accumulation of herpes simplex virus type 1 early and leaky-late proteins correlates with apoptosis prevention in infected human HEp-2 cells. J. Virol. 75:1013-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beg, A. A., and D. Baltimore. 1996. An essential role for NF-κB in preventing TNF-α-induced cell death. Science 274:782-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockman, J. A., D. C. Scherer, T. A. McKinsey, S. M. Hall, X. Qi, W. Y. Lee, and D. W. Ballard. 1995. Coupling of a signal response domain in IκBα to multiple pathways for NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2809-2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Z., J. Hagler, V. J. Palombella, F. Melandri, D. Scherer, D. Ballard, and T. Maniatis. 1995. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets IκBα to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 9:1586-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou, J., J. J. Chen, M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1995. Association of a M(r) 90,000 phosphoprotein with protein kinase PKR in cells exhibiting enhanced phosphorylation of translation initiation factor eIF-2 alpha and premature shutoff of protein synthesis after infection with gamma 134.5− mutants of herpes simplex virus 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10516-10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dechend, R., F. Hirano, K. Lehmann, V. Heissmeyer, S. Ansieau, F. G. Wulczyn, C. Scheidereit, and A. Leutz. 1999. The Bcl-3 oncoprotein acts as a bridging factor between NF-κB/Rel and nuclear co-regulators. Oncogene 18:3316-3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delhase, M., M. Hayakawa, Y. Chen, and M. Karin. 1999. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science 284:309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiDonato, J. A., M. Hayakawa, D. M. Rothwarf, E. Zandi, and M. Karin. 1997. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature 388:548-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finco, T. S., and A. S. Baldwin. 1995. Mechanistic aspects of NF-κB regulation: the emerging role of phosphorylation and proteolysis. Immunity 3:263-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita, T., G. Nolan, H. Liou, M. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 encodes a transcriptional coactivator that activates through NF-κB p50 homodimers. Genes Dev. 7:1354-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh, S., M. J. May, and E. B. Kopp. 1998. NF-κB and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:225-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodkin, M. L., A. T. Ting, and J. A. Blaho. 2003. NF-κB is required for apoptosis prevention during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 77:7261-7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He, B., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1997. The gamma(1)34.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1alpha to dephosphorylate the alpha subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:843-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilton, M. J., D. Mounghane, T. McLean, N. V. Contractor, J. O'Neil, K. Carpenter, and S. L. Bachenheimer. 1995. Induction by herpes simplex virus of free and heteromeric forms of E2F transcription factor. Virology 213:624-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu, Y., V. Baud, M. Delhase, P. Zhang, T. Deerinck, M. Ellisman, R. Johnson, and M. Karin. 1999. Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKKα subunit of IκB kinase. Science 284:316-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jerome, K. R., R. Fox, Z. Chen, A. E. Sears, H. Lee, and L. Corey. 1999. Herpes simplex virus inhibits apoptosis through the action of two genes, Us5 and Us3. J. Virol. 73:8950-8957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krug, A., G. D. Luker, W. Barchet, D. A. Leib, S. Akira, and M. Colonna. 2004. Herpes simplex virus type 1 activates murine natural interferon-producing cells through toll-like receptor 9. Blood 103:1433-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar, A., J. Haque, J. Lacoste, J. Hiscott, and B. R. Williams. 1994. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase activates transcription factor NF-κB by phosphorylating IκB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:6288-6292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurt-Jones, E. A., M. Chan, S. Zhou, J. Wang, G. Reed, R. Bronson, M. M. Arnold, D. M. Knipe, and R. W. Finberg. 2004. Herpes simplex virus 1 interaction with Toll-like receptor 2 contributes to lethal encephalitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:1315-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, F. S., J. Hagler, Z. J. Chen, and T. Maniatis. 1997. Activation of the IκBα kinase complex by MEKK1, a kinase of the JNK pathway. Cell 88:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leopardi, R., and B. Roizman. 1996. The herpes simplex virus major regulatory protein ICP4 blocks apoptosis induced by the virus or by hyperthermia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9583-9587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leopardi, R., C. Van Sant, and B. Roizman. 1997. The herpes simplex virus 1 protein kinase US3 is required for protection from apoptosis induced by the virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7891-7896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Q., Q. Lu, J. Y. Hwang, D. Buscher, K. F. Lee, J. C. Izpisua-Belmonte, and I. M. Verma. 1999. IKK1-deficient mice exhibit abnormal development of skin and skeleton. Genes Dev. 13:1322-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Q., D. Van Antwerp, F. Mercurio, K. F. Lee, and I. M. Verma. 1999. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IκB kinase 2 gene. Science 284:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, X., P. E. Massa, A. Hanidu, G. W. Peet, P. Aro, A. Savitt, S. Mische, J. Li, and K. B. Marcu. 2002. IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ are each required for the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response program. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45129-45140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, Z. W., W. Chu, Y. Hu, M. Delhase, T. Deerinck, M. Ellisman, R. Johnson, and M. Karin. 1999. The IKKβ subunit of IκB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor κB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 189:1839-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ling, L., Z. Cao, and D. V. Goeddel. 1998. NF-κB-inducing kinase activates IKK-α by phosphorylation of Ser-176. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3792-3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, Z. G., H. Hsu, D. V. Goeddel, and M. Karin. 1996. Dissection of TNF receptor 1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-κB activation prevents cell death. Cell 87:565-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madrid, L. V., C. Y. Wang, D. C. Guttridge, A. J. Schottelius, A. S. Baldwin, Jr., and M. W. Mayo. 2000. Akt suppresses apoptosis by stimulating the transactivation potential of the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1626-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maran, A., R. K. Maitra, A. Kumar, B. Dong, W. Xiao, G. Li, B. R. Williams, P. F. Torrence, and R. H. Silverman. 1994. Blockage of NF-κB signaling by selective ablation of an mRNA target by 2-5A antisense chimeras. Science 265:789-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medici, M. A., M. T. Sciortino, D. Perri, C. Amici, E. Avitabile, M. Ciotti, E. Balestrieri, E. De Smaele, G. Franzoso, and A. Mastino. 2003. Protection by herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D against Fas-mediated apoptosis: role of nuclear factor κB. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36059-36067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medzhitov, R. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1:135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercurio, F., H. Zhu, B. W. Murray, A. Shevchenko, B. L. Bennett, J. Li, D. B. Young, M. Barbosa, M. Mann, A. Manning, and A. Rao. 1997. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science 278:860-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemoto, S., J. A. DiDonato, and A. Lin. 1998. Coordinate regulation of IκB kinases by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 and NF-κB-inducing kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7336-7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olgiate, J., G. L. Ehmann, S. Vidyarthi, M. J. Hilton, and S. L. Bachenheimer. 1999. Herpes simplex virus induces intracellular redistribution of E2F4 and accumulation of E2F pocket protein complexes. Virology 258:257-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orian, A., H. Gonen, B. Bercovich, I. Fajerman, E. Eytan, A. Israel, F. Mercurio, K. Iwai, A. L. Schwartz, and A. Ciechanover. 2000. SCFβ-TrCP ubiquitin ligase-mediated processing of NF-κB p105 requires phosphorylation of its C-terminus by IκB kinase. EMBO J. 19:2580-2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel, A., J. Hanson, T. I. McLean, J. Olgiate, M. Hilton, W. E. Miller, and S. L. Bachenheimer. 1998. Herpes simplex type 1 induction of persistent NF-κB nuclear translocation increases the efficiency of virus replication. Virology 247:212-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sizemore, N., N. Lerner, N. Dombrowski, H. Sakuria, and G. R. Stark. 2001. Distinct roles of the IκB kinase α and beta subunits in liberating NFκB from IκB and in phosphorylating the p65 subunit of NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3863-3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun, S., J. Elwood, and W. C. Greene. 1996. Both amino- and carboxyl-terminal sequences within IκBα regulate its inducible degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1058-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taddeo, B., T. R. Luo, W. Zhang, and B. Roizman. 2003. Activation of NF-κB in cells productively infected with HSV-1 depends on activated protein kinase R and plays no apparent role in blocking apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12408-12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takaesu, G., R. M. Surabhi, K. J. Park, J. Ninomiya-Tsuji, K. Matsumoto, and R. B. Gaynor. 2003. TAK1 is critical for IκB kinase-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 326:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeda, K., O. Takeuchi, T. Tsujimura, S. Itami, O. Adachi, T. Kawai, H. Sanjo, K. Yoshikawa, N. Terada, and S. Akira. 1999. Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKα. Science 284:313-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Traenckner, E. B., H. L. Pahl, T. Henkel, K. N. Schmidt, S. Wilk, and P. A. Baeuerle. 1995. Phosphorylation of human IκB-α on serines 32 and 36 controls IκB-α proteolysis and NF-κB activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 14:2876-2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ueberla, K., Y. Lu, E. Chung, and W. A. Haseltine. 1993. The NF-κB p65 promoter. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 6:227-230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Antwerp, D. J., S. J. Martin, T. Kafri, D. R. Green, and I. M. Verma. 1996. Suppression of TNF-α-induced apoptosis by NF-κB. Science 274:787-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verma, U. N., Y. Yamamoto, S. Prajapati, and R. B. Gaynor. 2004. Nuclear role of IκB kinase-γ/NF-κB essential modulator (IKKγ/NEMO) in NF-κB-dependent gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 279:3509-3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, C. Y., M. W. Mayo, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1996. TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-κB. Science 274:784-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whiteside, S. T., M. K. Ernst, O. LeBail, C. Laurent-Winter, N. Rice, and A. Israel. 1995. N- and C-terminal sequences control degradation of MAD3/IκBα in response to inducers of NF-κB activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5339-5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woronicz, J. D., X. Gao, Z. Cao, M. Rothe, and D. V. Goeddel. 1997. IκB kinase−: NF-B activation and complex formation with IB kinase− and NIK. Science 278:866-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto, Y., U. N. Verma, S. Prajapati, Y. T. Kwak, and R. B. Gaynor. 2003. Histone H3 phosphorylation by IKK-alpha is critical for cytokine-induced gene expression. Nature 423:655-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, Y. L., L. F. Reis, J. Pavlovic, A. Aguzzi, R. Schafer, A. Kumar, B. R. Williams, M. Aguet, and C. Weissmann. 1995. Deficient signaling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 14:6095-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yurochko, A., T. Kowalik, S. Huong, and E. Huang. 1995. Human cytomegalovirus upregulates NF-κB activity by transactivating the NF-κB p105/p50 and p65 promoters. J. Virol. 69:5391-5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yurochko, A. D., E. S. Hwang, L. Rasmussen, S. Keay, L. Pereira, and E. S. Huang. 1997. The human cytomegalovirus UL55 (gB) and UL75 (gH) glycoprotein ligands initiate the rapid activation of Sp1 and NF-κB during infection. J. Virol. 71:5051-5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zamanian-Daryoush, M., T. H. Mogensen, J. A. DiDonato, and B. R. Williams. 2000. NF-κB activation by double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) is mediated through NF-κB-inducing kinase and IκB kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1278-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zandi, E., D. M. Rothwarf, M. Delhase, M. Hayakawa, and M. Karin. 1997. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell 91:243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao, Q., and F. S. Lee. 1999. Mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinases 2 and 3 activate nuclear factor-κB through IκB kinase-α and IκB kinase-β. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8355-8358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou, G., E. Avitabile, G. Campadelli-Fiume, and B. Roizman. 2003. The domains of glycoprotein D required to block apoptosis induced by herpes simplex virus 1 are largely distinct from those involved in cell-cell fusion and binding to nectin1. J. Virol. 77:3759-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou, G., V. Galvan, G. Campadelli-Fiume, and B. Roizman. 2000. Glycoprotein D or J delivered in trans blocks apoptosis in SK-N-SH cells induced by a herpes simplex virus 1 mutant lacking intact genes expressing both glycoproteins. J. Virol. 74:11782-11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou, G., and B. Roizman. 2001. The domains of glycoprotein D required to block apoptosis depend on whether glycoprotein D is present in the virions carrying herpes simplex virus 1 genome lacking the gene encoding the glycoprotein. J. Virol. 75:6166-6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]