Abstract

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) and flatfoot are common pediatric orthopedic disorders, being referred to and managed by both general and pediatric orthopedic surgeons, through various modalities. Our study aimed to evaluate their consensus and perspective disagreements in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches of the mentioned deformities. Forty participants in two groups of general orthopedic surgeons (GOS) (n=20) and pediatric orthopedic surgeons (POS) (n=20), were asked to answer an 8-item questionnaire on DDH and flexible flatfoot. The questions were provided with two- or multiple choices and a single choice was accepted for each one. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests was performed to compare the responses. For a neonate with limited hip abduction, hip ultrasonography was the agreed-upon approach in both groups (100% POS vs 71% GOS), and for its interpretation 79% of POS relied on their own whereas 73% of GOS relied on radiologist’s report (P=0.002). In failure of a 3-week application of the Pavlik harness, ending it and closed reduction (57% POS vs. 41% GOS) followed by surgery quality assessment with CT scan (64% POS vs. 47% GOS) and without the necessity for avascular necrosis evaluation (79% POS vs. 73% GOS) were the choice measures. In case of closed reduction failure, open reduction via medial approach was the favorite next step in both groups (62% POS and 80% GOS). For the patient with flexible flat foot, reassurance was the choice plan of 79% of pediatric orthopedists. Our findings demonstrated significant disagreements among the orthopedic surgeons. This proposes insufficiency of high-level evidence.

Keywords: Congenital hip dislocation, Consensus, Flatfoot, Orthopedics, Pediatrics

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a major cause of physical disability in children, is one of the most prevalent congenital disorders which may rarely develop after the neonatal period (1, 2). It is thought to be associated with early-onset osteoarthritis in adults, especially in those who receive late treatments (3). Hip instability at birth has a prevalence of 0.16% to 2.85% in infants on physical examination (4). There seems to be neither a diagnostic gold standard nor any strong expert consensus among orthopedic surgeons on DDH (5). In some recent studies, pediatric orthopedic surgeons have been asked to rate a set of diagnostic criteria for DDH. Consistency has been reported to be poor for domains of patient history, ultrasonography and radiography, while it was acceptable (not good) only for clinical examination. Also, a considerable geographic variation was obvious in terms of how the surgeons assigned important ratings of the criteria. These findings probably imply distinct prevalence estimates and management standards of DDH in different regions (6).

Flatfoot (pes planus) is a common childhood condition in which the medial longitudinal arch is decreased or completely absent. It ranges from painless, flexible and physiological growth variants in most cases to painful, rigid, and pathological presentations of bone, collagen or neurological disorders (7). Ligamentous laxity usually improves through development of an arch by 10 years of age. If not so, more likely when there is a positive family history of flatfoot, it may become persistent as in 15-23% of adults (8). Treatment for painless flexible flatfoot is controversial and yet not supported by adequate evidence. However, in case of a rigid or painful flatfoot, orthotics or surgery is probably required, mainly in symptomatic ones (9). Although prescription of orthotics causes no harm, even if not indicated, negative psychological impacts have been reported in those who wore orthotics in childhood (10). Of note, children with DDH have a higher incidence of flatfoot during late childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Thus, it is proposed that these two disorders have a common etiology (11).

Both general and pediatric orthopedic surgeons frequently deal with children having such deformities. With regard to regional variety of strategies and absence of globally agreed-on gold standards, it would be interesting to compare these specialists in one country and examine the extent of their agreements on mutual subjects.

To do so, our study aimed to evaluate the consensus and viewpoint differences between general and pediatric orthopedic surgeons on their approaches to diagnose and treat two common disorders of pediatric orthopedics; i.e., DDH and flexible flatfoot.

Materials and Methods

Forty orthopedic surgeons in two groups of general orthopedic surgeons (GOS) (n=20) and pediatric orthopedic surgeons (POS) (n=20) were asked to take an eight-item survey which comprised questions with two- or multiple choices focusing on DDH and flexible flatfoot [Table 1]. In terms of clinical orthopedic experience, half surgeons in both groups had practiced a minimum ten years and the other half had worked for at least one year. All pediatric orthopedic surgeons had completed pediatric surgery fellowship trainings. All general orthopedic surgeons had achieved orthopedic surgery board certificate and none of them had taken any further subspecialty courses. Participants voted by an electronic keypad in order to enhance the precision of answering process. They were requested to answer each question with a single choice. This study was performed during yearly gathering of members of Iranian Orthopedic Association and members of Persian Orthopedic Trauma Association (POTA) at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in 2015.

Table 1.

Eight-item questionnaire

| DDH | |

| Q1 | What’s the first step in a 3-day-old neonate with limited hip abduction? A. Hip ultrasonography, always B. Pelvic x-ray, always C. X-ray, if there is no reliable ultrasonography D. Pavlik or abduction brace without any further work up |

| Q2 | What’s the most important factor for you in interpretation of ultrasonography? A. The radiologist’s report B. My own interpretation |

| Q3 | What’s the next step in management of DDH after 3 weeks of failure in treatment with Pavlik harness? A. Continuing Pavlik harness treatment until 3 months of age B. Correcting Pavlik harness position C. Ending treatment with Pavlik harness and considering closed reduction D. Ending treatment with Pavlik harness and considering open reduction E. I have my own method of treatment |

| Q4 | After Pavlik harness treatment with no success (>3 weeks), would you assess the patient for possible avascular necrosis before closed/open reduction? A. Yes B. No |

| Q5 | How do you assess the vascularity of the femoral head? A. MRI B. Doppler ultrasonography C. Bone scan D. None |

| Q6 | If you choose closed reduction for treatment, how would you assess the quality of reduction following surgery? A. X-ray B. Ultrasonography C. CT scan D. MRI E. Arthrography |

| Q7 | What’s the next step if the closed reduction is not successful in a 5-month-old child? A. Open reduction via medial approach B. Open reduction via anterior approach C. Open reduction and salter osteotomy after 1 year D. I have my own approach |

| Flexible flat foot | |

| Q8 | What’s your plan for a 4-year-old girl with flexible flat foot? A. Reassurance B. In-shoe foot orthosis C. Footwear D. Rehabilitation therapy exercise E. Longitudinal arch support |

Data analysis was performed by SPSS software (version 19.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All frequencies are expressed as percentage. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were performed to compare the variables. A P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

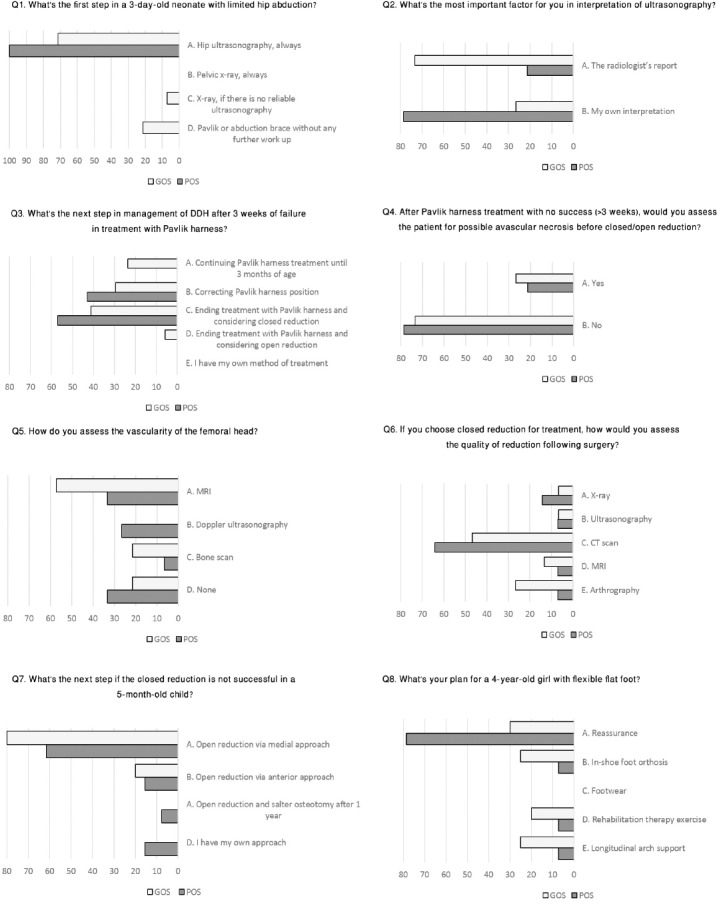

Hip ultrasonography was the agreed-upon first step for a 3-day-old neonate with limited hip abduction by all surgeons [Figure 1, Q1]. All pediatric orthopedic surgeons and 71% of general orthopedic surgeons opted for hip ultrasonography (P= 0.037).

Figure 1.

Orthopedic surgeons’ perception on management of Developmental Dysplasia of Hip and Flexible Flatfoot.

The method of interpreting hip ultrasonography [Figure 1, Q2] showed a significant difference in point of view between two groups (χ(2) (1) = 9.14, P= 0.002). Pediatric orthopedic surgeons usually used their own experience for interpretation of hip ultrasonography images (79%), while general orthopedic surgeons relied on the radiologist’s report (73%).

To reduce the hip after failure of a 3-week application of the Pavlik harness [Figure 1, Q3], the most common strategy was ending the treatment with Pavlik harness and considering closed reduction in both groups (57% POS and 41% GOS, P= 0.19). Correcting the Pavlik harness position was the next (43% POS and 29% GOS). None of the pediatric orthopedic surgeons selected other options, while 24% of general orthopedic surgeons decided to continue the Pavlik harness treatment until 3 months of age.

Majority of surgeons (79% POS and 73% GOS) in both groups (P=1.00) believed that it is not necessary to evaluate the patient for possible avascular necrosis before closed/open reduction after a period (>3-week) of unsuccessful Pavlik harness treatment [Figure 1, Q4].

There was no agreement on the method for evaluation of the femoral head vascularity [Figure 1, Q5] especially among pediatric orthopedic surgeons (P=0.5). General orthopedic surgeons tended to use MRI for it (57%).

To assess the quality of surgery following closed reduction for DDH [Figure 1, Q6], CT scan was the first choice in both groups (64% POS and 47% GOS, P=0.71).

After unsuccessful closed reduction of a 5-month-old child with DDH [Figure 1, Q7], open reduction via medial approach was the most common reply in both groups (62% POS and 80% GOS, P=0.32). None of the general orthopedic surgeons and 15% percent of pediatric orthopedic surgeons stated that they have their own approach for handling the situation.

Reassurance was the treatment plan of 79% of pediatric orthopedic surgeons (P=0.06) for a 4-year-old girl with flexible flatfoot [Figure 1, Q8]. No one chose footwear in both groups.

Discussion

This investigation aimed to evaluate the extent of consensus between general and pediatric orthopedic surgeons on management of DDH and flexible flatfoot as two common orthopedic disorders among prepubescent children. We found considerable disagreements between these two groups dealing with the sample cases.

It would be clinically and medico-legally beneficial if further concord is achieved on such contentious issues among all (sub) specialties involved in. The consensus could be based on a spectrum from evidence-based clinical practice guidelines to even insufficient evidences. An example of such guidelines is the one on detection and management of DDH which has been endorsed by American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (12).

DDH includes a whole range of deformities involving the growing hip such as frank dislocation, subluxation, instability, and dysplasia of the femoral head and acetabulum (13). There was an approach similarity between the two groups on DDH-related issues in this study. The ultrasonography was preferred by both groups of surgeons for early diagnosis. The standard real-time ultrasonography is an accurate hip imaging method especially during the first few months of life when radiographs are not reliable enough (14, 15). Although ultrasonography screening of newborns is not recommended, it is the preferred technique for evaluation of a high-risk infant (12, 16). In the current study, unlike general orthopedic surgeons, majority of pediatric orthopedic surgeons used their own experience for interpretation of hip ultrasonography. This is probably because of curricular imaging trainings during their fellowship programs.

The goal of treatment is to relocate the joint and acquire a stable hip joint at the earliest possible age with minimal complications (17). Pavlik harness is the most commonly used device to treat hip instability in infants (18). For patients who failed to achieve stable reduction with the Pavlik harness, a closed reduction of the hip joint is indicated. Majority of surgeons in this study settled closed reduction after failure of treatment with Pavlik harness. Surprisingly, 24% of general orthopedic surgeons insisted on continuing the Pavlik harness treatment after 3 weeks, while it has been recommended to discontinue the use of Pavlik harness if the hips are not reduced within 3 weeks (19). This malpractice is probably due to the absence of clear, widely accepted criteria to define successful or failed treatment for DDH (12).

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head is iatrogenic and not part of the natural history of DDH (20). It was proposed that the cartilaginous femoral head without an ossific nucleus is more susceptible to ischemia than a developed femoral head with ossific nucleus (21). However, the prognostic effect of the ossific nucleus is in question now (22, 23). After the introduction of the safe zone (which is the range between maximal passive abduction of the hip and the abduction angle where the femoral head becomes unstable) the iatrogenic AVN associated with Pavlik treatment has reduced (24). Majority of surgeons in the current study did not assess the patient for possible AVN before closed reduction after a period of unsuccessful Pavlik harness treatment. It may seem that they were not concerned with AVN, which is not right. The main cause, as we asked, is that the result of evaluation does not affect the next step. Therefore, many surgeons find this unnecessary. We strongly oppose, and believe that AVN will influence the outcome of closed/open reduction and skipping its evaluation may have legal consequences for the physician and hospital and therefore, should be addressed.

Different approaches are available for open reduction. Medial approach was the most popular approach in this study. This approach demands minimal dissection and avoids splitting of the iliac apophysis. Another advantage is direct access to the medial structures (25). In a recent comparative investigation, medial and anterior approaches of open reduction of DDH showed no significant outcome difference in terms of AVN and the need for further corrective operations (26). However, some other studies have reported an association between the medial approach and osteonecrosis, as a result of the injury to the blood supply of the femoral head (27). In anterior approach, more dissection is required, but the approach allows for more exploration and routine capsulorrhaphy (28-30).

There was no agreement between the two groups on the flexible flatfoot treatment options. In contrast to the general orthopedic surgeons, there was a good consensus on reassurance in the pediatric orthopedic surgeons group. The evidence for efficacy of nonsurgical interventions for flexible flatfoot is very limited and inconclusive. Consequently, education and reassurance remain the mainstay of treatment (9).

Lack of consensus on management approaches of common cases of pediatrics orthopedics highlights the need for more comprehensive investigations to achieve higher levels of clinical evidence. Knowing the fact that orthopedic disorders of children comprise a large number of visits, better coordination and cooperation between general and pediatric orthopedic surgeons is of great importance to attain uniformity, maximize diagnostic and therapeutic yield and minimize unnecessary work-up. Existing accredited guidelines can play a pivotal role in this matter and should be of consideration.

References

- 1.Leck I. Congenital dislocation of the hip. Oxford: Antenatal and Neonatal Screening Ed; 2000. pp. 398–424. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwend RM, Schoenecker P, Richards BS, Flynn JM, Vitale M. Screening the newborn for developmental dysplasia of the hip: now what do we do? J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):607–10. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318142551e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson JC, Runge MM, Nye NS. Common questions about developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(12):843–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1541–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60710-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roposch A, Wright JG. Increased diagnostic information and understanding disease: uncertainty in the diagnosis of developmental hip dysplasia 1. Radiology. 2007;242(2):355–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams D, Protopapa E, Stohr K, Hunter JB, Roposch A. The most relevant diagnostic criteria for developmental dysplasia of the hip: a study of British specialists. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0867-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dare DM, Dodwell ER. Pediatric flatfoot: cause, epidemiology, assessment, and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(1):93–100. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosalkar HS, Spiegel DA, Davidson RS. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. The foot and toes. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jane MacKenzie A, Rome K, Evans AM. The efficacy of nonsurgical interventions for pediatric flexible flat foot: a critical review. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(8):830–4. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3182648c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driano AN, Staheli L, Staheli LT. Psychosocial development and corrective shoewear use in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18(3):346–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponce de León Samper MC, Herrera Ortiz G, Castellanos Mendoza C. Relationship between flexible flat foot and developmental hip dysplasia. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59(5):295–8. doi: 10.1016/j.recot.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulpuri K, Song KM, Gross RH, Tebor GB, Otsuka NY, Lubicky JP, et al. The American academy of orthopaedic surgeons evidence-based guideline on detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(20):1717–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guille JT, Pizzutillo PD, MacEwen GD. Development dysplasia of the hip from birth to six months. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(4):232–42. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vedantam R, Bell MJ. Dynamic ultrasound assessment for monitoring of treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(6):725–8. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199511000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castelein RM, Sauter AJ. Ultrasound screening for congenital dysplasia of the hip in newborns: its value. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8(6):666–70. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198811000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paton RW, Hinduja K, Thomas CD. The significance of at-risk factors in ultrasound surveillance of developmental dysplasia of the hip. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1264–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B9.16565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malvitz TA, Weinstein SL. Closed reduction for congenital dysplasia of the hip. Functional and radiographic results after an average of thirty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(12):1777–92. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mubarak SJ, Bialik V. Pavlik: the man and his method. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(3):342–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiruveedhula M, Reading IC, Clarke NM. Failed Pavlik harness treatment for DDH as a risk factor for avascular necrosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(2):140–3. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas SR. A review of long-term outcomes for late presenting developmental hip dysplasia. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(6):729–33. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B6.35395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luhmann SJ, Schoenecker PL, Anderson AM, Bassett GS. The prognostic importance of the ossific nucleus in the treatment of congenital dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1719–27. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sllamniku S, Bytyqi C, Murtezani A, Haxhija EQ. Correlation between avascular necrosis and the presence of the ossific nucleus when treating developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Child Orthop. 2013;7(6):501–5. doi: 10.1007/s11832-013-0538-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roposch A, Stohr KK, Dobson M. The effect of the femoral head ossific nucleus in the treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):911–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotlarsky P, Haber R, Bialik V, Eidelman M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: What has changed in the last 20 years? World J Orthop. 2015;6(11):886–901. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i11.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada K, Mihara H, Fujii H, Hachiya M. A long-term follow-up study of open reduction using Ludloff’s approach for congenital or developmental dislocation of the hip. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3(1):1–6. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.31.2000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoellwarth JS, Kim YJ, Millis MB, Kasser JR, Zurakowski D, Matheney TH. Medial versus anterior open reduction for developmental hip dislocation in age-matched patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):50–6. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koizumi W, Moriya H, Tsuchiya K, Takeuchi T, Kamegaya M, Akita T. Ludloff’s medial approach for open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip. A 20-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(6):924–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x78b6.6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinstein SL. Closed versus open reduction of congenital hip dislocation in patients under 2 years of age. Orthopedics. 1990;13(2):221–7. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19900201-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalamchi A, Schmidt TL, MacEwen GD. Congenital dislocation of the hip. Open reduction by the medial approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;169(1):127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mau H, Dorr WM, Henkel L, Lutsche J. Open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip by Ludloff’s method. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(7):1281–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]