Abstract

Background/Aims

There have been controversial reports linking Helicobacter pylori infection to autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD). However, data regarding the relationship are limited for Asian populations, which have an extremely high prevalence of H. pylori infection. We performed this study to investigate the association between H. pylori infection and AITD in Koreans.

Methods

This study involved adults aged 30 to 70 years who had visited a health promotion center. A total of 5,502 subjects were analysed. Thyroid status was assessed by free thyroxine, thyroid stimulating hormone, and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to H. pylori were measured as an indication of H. pylori infection. We compared the prevalence of TPO-Ab in subjects with and without H. pylori infection.

Results

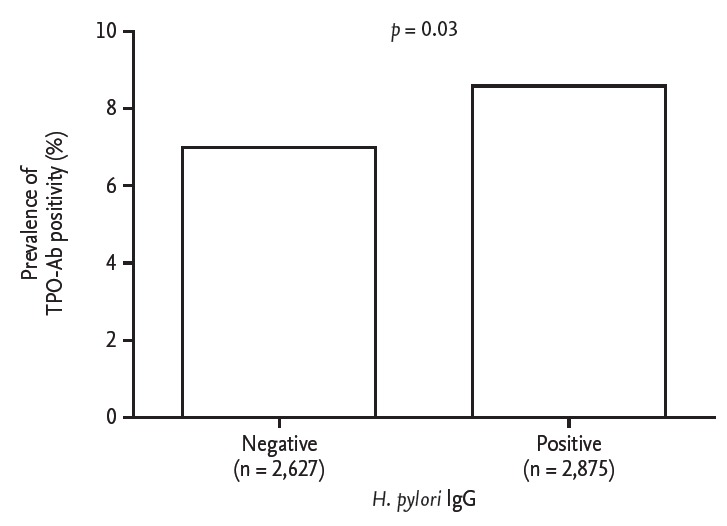

H. pylori IgG antibodies were found in 2,875 subjects (52.3%), and TPO-Ab were found in 430 (7.8%). Individuals positive for H. pylori Ab were older than those negative for H. pylori Ab (p < 0.01). The proportion of females was significantly higher in the TPO-Ab positive group (41.0% vs. 64.2%, p < 0.01). Prevalence of TPO-Ab positivity was higher in subjects with H. pylori infection (8.6% vs. 7.00%, p = 0.03), and this association was significant after adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.00 to 1.03; p = 0.04).

Conclusions

In our study, prevalence of TPO-Ab positivity is more frequent in subjects with H. pylori infection. Our findings suggest H. pylori infection may play a role in the development of autoimmune thyroiditis.

Keywords: Thyroid, Autoimmunity, Helicobacter pylori

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), one of the most common autoimmune diseases, had several pathogenesis, including both genetic and environmental factors and is one of risk factor for thyroid dysfunction [1,2]. One of potential environmental causes are infectious agents such as Helicobacter pylori, which may cause chronic inflammation and autoimmune reactivity in susceptible subjects [3,4]. Although some studies support a role for H. pylori in AITD, this remains controversial [5-14].

H. pylori infection was prevalent in Asian populations in the last 10 years. Though the prevalence of H. pylori infection and annual reinfection rate found to be decreased especially below the age of 40’s after introduction of triple therapy, H. pylori infection is still prevalent in Korean population [15]. The incidence of H. pylori infection in the Korean population above 16 years of age was 59.6% in 2005 [15]. Furthermore, extra-gastric diseases, especially autoimmune diseases that might be related to H. pylori infection have received attention recently [16,17]. However, data regarding the relationship between H. pylori infection and thyroid autoimmunity are limited in Asian populations, in which H. pylori infection is extremely prevalent.

In the present study we investigated the association between H. pylori infection and AITD in the Korean population. Our findings indicated that thyroid autoimmunity is significantly associated with H. pylori infection.

METHODS

Subjects

This study was performed in adults aged 30 to 70 years (median, 52) who had visited the health promotion center at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, from January 2009 to December 2009. Subjects who checked for serum levels of free thyroxine (T4), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) and H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were included. We excluded subjects with previous histories or family histories of thyroid disease.

Laboratory measurements

Thyroid assessment was done by free T4, TSH, and TPO-Ab. Serum TPO-Ab concentrations were determined using a BRAHMS anti-TPOn radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (Thermo Scientific, Bonn, Germany) with a functional sensitivity of 30 U/mL. TPO-Ab levels exceeding 60 U/mL were considered positive for TPO-Ab. Levels of serum TSH and free T4 were measured using a TSH-CTK-3 immunoradiometric assay kit (DiaSorin S.p.A, Saluggia, Italy) and a FT4 RIA kit (Beckman Coulter, IMMUNOTECH, Prague, Czech Republic), respectively.

Our center uses the Immulite 2000 H. pylori IgG system (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) to measure anti-H. pylori IgG [18]. This test consists of a solid-phase, 2-step, chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay.

Definitions

We defined thyroid autoimmunity as positive TPO-Ab, irrespective of the presence of thyroid dysfunction. H. pylori infection was defined as positive for IgG antibodies to H. pylori. In our center, the results of H. pylori IgG were reported as positive (> 1.5U/mL), equivocal (0.9 to 1.5U/mL), and negative (< 0.9U/mL) [19]. Subjects with equivocal H. pylori IgG results were excluded.

Age was stratified by quartile. The quartiles were 30 to 45 years (Q1), 46 to 51 years (Q2), 52 to 56 years (Q3), and 57 to 70 years (Q4).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as numbers (percentages). For categorical variables comparisons between groups were performed using the chi-square test and Fisher exact test (two-sided). Multivariate analysis was carried out using a binary logistic regression model. The R software package version 3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org) was used for statistical analysis. All p values were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered to denote statistical significance.

RESULTS

A total of 5,967 subjects without past or family histories of thyroid disease were included. Of these, 465 subjects with equivocal results for H. pylori IgG antibody were excluded. Finally 5,502 subjects (female 42.8%) were analysed. The mean age was 51.9 years. H. pylori infection was found in 2,875 subjects (52.3%), and thyroid autoimmunity was present in 430 (7.8%).

The clinical characteristics of the subjects according to H. pylori infection and thyroid autoimmunity are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Subjects with H. pylori infection were older than those without H. pylori infection (p < 0.01), and there were significant differences between the age quartiles in the frequency of H. pylori infection. The proportions of individuals positive for H. pylori Ab were 46.1%, 56.1%, 52.0%, and 53.5%, in Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4, respectively (p < 0.01) (Table 1). On the other hand, the proportion of females was significantly higher in the TPO-Ab positive group than in the TPO-Ab negative group (64.2% vs. 41.0%, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects according to Helicobacter pylori immunoglobulin G antibody status

| Characteristic | Total (n = 5,502) | H. pylori Ab (–) (n = 2,627) | H. pylori Ab (+) (n = 2,875) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 51.9 ± 8.3 | 51.4 ± 8.6 | 52.2 ± 8.0 | < 0.01 |

| Age quartilea | < 0.01 | |||

| Q1 | 1,183 | 637 (53.8) | 546 (46.1) | |

| Q2 | 1,477 | 649 (43.9) | 828 (56.1) | |

| Q3 | 1,268 | 609 (48.0) | 659 (52.0) | |

| Q4 | 1,574 | 732 (46.5) | 842 (53.5) | |

| Female sex | 2,353 (42.8) | 1,131 (43.1) | 1,653 (57.5) | 0.70 |

| TSH, mU/Lb | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 2.1 | 2.2 ± 2.0 | 0.08 |

| Free T4, ng/dL | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.06 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

Ab, antibody; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; T4, thyroxine.

Age was stratified by quartile. The quartiles were 30 to 45 (Q1), 46 to 51 (Q2), 52 to 56 (Q3), and 57 to 70 (Q4).

Geometric mean.

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects according to TPO-Ab status

| Characteristic | Total (n = 5,502) | TPO-Ab (–) (n = 5,072) | TPO-Ab (+) (n = 430) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 51.9 ± 8.3 | 51.8 ± 8.3 | 52.6 ± 8.1 | 0.05 |

| Age quartilea | 0.34 | |||

| Q1 | 1,183 | 1,094 (92.3) | 89 (7.5) | |

| Q2 | 1,477 | 1,375 (93.1) | 102 (6.9) | |

| Q3 | 1,268 | 1,164 (91.8) | 104 (8.2) | |

| Q4 | 1,574 | 1,439 (91.4) | 135 (8.6) | |

| Female sex | 2,353 (42.8) | 2,077 (41.0) | 276 (64.2) | < 0.01 |

| TSH, mU/Lb | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 2.7 ± 3.0 | < 0.01 |

| Free T4, ng/dL | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.29 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

TOP-Ab, thyroid peroxidase antibody; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; T4, thyroxine.

Age was stratified by quartile. The quartiles were 30 to 45 (Q1), 46 to 51 (Q2), 52 to 56 (Q3), and 57 to 70 (Q4).

Geometric mean.

We compared thyroid autoimmunity according to H. pylori infection. Prevalence of TPO-Ab positivity was higher in subjects with H. pylori infection (246 out of 2,875 subjects [8.6%] vs. 184 out of 2,627 subjects [7.0%], p = 0.03) (Fig. 1). We performed a multivariate analysis to adjust for the possible interaction between thyroid autoimmunity and various clinical parameters. The serologic results of H. pylori were significantly related to TPO-Ab positivity after adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.00 to 1.03; p = 0.04).

Figure. 1.

Proportion of individuals positive for antithyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) according to Helicobacter pylori infection status. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

DISCUSSION

Infectious agents have been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity [20]. Epidemiological and serological surveys have suggested the possibility of a link between Yersina enterocolitica infection and Graves disease, a link which might be explained by molecular mimicry [21,22]. Infectious agents may lead to thyroid autoimmunity by a variety of mechanisms, such as inducing modification of self-antigens, mimicry of self-molecules, activation of polyclonal T cells, alteration of the idiotype network, formation of immune complexes, and induction of major histocompatibility complex molecules on thyroid epithelial cells [4]. A homologous 11-residue peptide in both gastric parietal cell antigen and thyroid peroxidase suggests the existence of an epitope common to both of the two antigens [23]. There may be cross reaction between antibodies produced during H. pylori infection and thyroid antigens, leading to development of AITD. Interestingly, elevated chemokine response to H. pylori have been observed in AITD patients [24].

H. pylori is a spiral-shaped, flagellated, gram-negative bacterium, and colonizes the stomach of about 50% of the world’s population [16]. It can cause dyspepsia, acute and chronic gastritis, peptic ulceration, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma. In particular, the most virulent strain of H. pylori was identified by the presence of cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), and individuals infected with the CagA-positive strain of H. pylori have an increased risk of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [25]. Furthermore, several studies have reported a significant correlation between CagA-positive strains and AITD. Because our study was based on data from health check-ups, CagA status was not investigated.

Previous studies regarding the association between H. pylori and AITD have generally been from Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Iran, in which H. pylori infections are prevalent. In Korea, the seroprevalence of H. pylori infection was 59.6% in 2005 and decreased to 54.4% in 2011, according to Lim et al. [26]. It is unclear whether the prevalence of H. pylori infection and a decreasing trend of H. pylori seroprevalence will affect the association between H. pylori and AITD.

Our study had several limitations. First, we defined H. pylori infection based on a serologic test, which detects both past and current infections. Second, our definition of AITD did not differentiate between Graves disease and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Third, we did not test for the presence of CagA because our study was based on health check-up data. Finally, there might be concern about false positive results in H. pylori IgG test and TPO-Ab assay. However, H. pylori IgG test is highly specific and had no cross-reactivity to Campylobacter coli microorganism. We also excluded patients with equivocal results to avoid a concern of false positive results. TPO-Ab assay has cross-reactivity with human anti-Tg antibodies and human Tg. However, anti-Tg antibody could one of other representative of thyroid autoimmunity and we excluded subjects with history of thyroid disease. Therefore, there might be little concern about false positive results.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that H. pylori infection may be associated with AITD. Further studies are needed to confirm the role of H. pylori infection in AITD.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Infectious agents have been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity.

2. In our study, prevalence of thyroid peroxidase antibody positivity is more frequent in subjects with Helicobacter pylori infection.

3. H. pylori infection may be associated with autoimmune thyroid disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (No. 2014-374) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Seoul, Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fountoulakis S, Tsatsoulis A. On the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disease: a unifying hypothesis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60:397–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2004.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YA, Park YJ. Prevalence and risk factors of subclinical thyroid disease. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2014;29:20–29. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2014.29.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hybenova M, Hrda P, Prochazkova J, Stejskal V, Sterzl I. The role of environmental factors in autoimmune thyroiditis. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010;31:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomer Y, Davies TF. Infection, thyroid disease, and autoimmunity. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:107–120. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassi V, Marino G, Iengo A, Fattoruso O, Santinelli C. Autoimmune thyroid diseases and Helicobacter pylori: the correlation is present only in Graves's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1093–1097. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i10.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertalot G, Montresor G, Tampieri M, et al. Decrease in thyroid autoantibodies after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 2004;61:650–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franceschi F, Satta MA, Mentella MC, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Helicobacter. 2004;9:369. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larizza D, Calcaterra V, Martinetti M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune thyroid disease in young patients: the disadvantage of carrying the human leukocyte antigen-DRB1*0301 allele. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:176–179. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papamichael KX, Papaioannou G, Karga H, Roussos A, Mantzaris GJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and endocrine disorders: is there a link? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2701–2707. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi WJ, Liu W, Zhou XY, Ye F, Zhang GX. Associations of Helicobacter pylori infection and cytotoxin-associated gene A status with autoimmune thyroid diseases: a meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2013;23:1294–1300. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soveid M, Hosseini Asl K, Omrani GR. Infection by Cag A positive strains of Helicobacter pylori is associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in Iranian patients. Iran J Immunol. 2012;9:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterzl I, Hrda P, Matucha P, Cerovska J, Zamrazil V. Anti-Helicobacter pylori, anti-thyroid peroxidase, anti-thyroglobulin and anti-gastric parietal cells antibodies in Czech population. Physiol Res. 2008;57 Suppl 1:S135–S141. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomasi PA, Dore MP, Fanciulli G, Sanciu F, Realdi G, Delitala G. Is there anything to the reported association between Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune thyroiditis? Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:385–388. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-1615-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassi V, Fattoruso O, Polistina MT, Santinelli C. Graves' disease shows a significant increase in the Helicobacter pylori recurrence. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 2014;81:784–785. doi: 10.1111/cen.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim N, Kim JJ, Choe YH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:269–278. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.5.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faria C, Zakout R, Araujo M. Helicobacter pylori and autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2013;67:347–349. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ram M, Barzilai O, Shapira Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori serology in autoimmune diseases: fact or fiction? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:1075–1082. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung JH, Choi KD, Han S, et al. Seroconversion rates of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korean adults. Helicobacter. 2013;18:299–308. doi: 10.1111/hel.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae SE, Jung HY, Kang J, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:60–67. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasserman EE, Nelson K, Rose NR, et al. Infection and thyroid autoimmunity: a seroepidemiologic study of TPOaAb. Autoimmunity. 2009;42:439–446. doi: 10.1080/08916930902787716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orgiazzi J. Thyroid autoimmunity. Presse Med. 2012;41(12 P 2):e611–e625. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prummel MF, Strieder T, Wiersinga WM. The environment and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:605–618. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elisei R, Mariotti S, Swillens S, Vassart G, Ludgate M. Studies with recombinant autoepitopes of thyroid peroxidase: evidence suggesting an epitope shared between the thyroid and the gastric parietal cell. Autoimmunity. 1990;8:65–70. doi: 10.3109/08916939008998434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stechova K, Pomahacova R, Hrabak J, et al. Reactivity to Helicobacter pylori antigens in patients suffering from thyroid gland autoimmunity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117:423–431. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636–1644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]