Abstract

During the papillomavirus (PV) life cycle, the L2 minor capsid protein enters the nucleus twice: in the initial phase after entry of virions into cells and in the productive phase to mediate encapsidation of the newly replicated viral genome. Therefore, we investigated the interactions of the L2 protein of bovine PV type 1 (BPV1) with the nuclear import machinery and the viral DNA. We found that BPV1 L2 bound to the karyopherin α2 (Kap α2) adapter and formed a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers. Previous data have shown that the positively charged termini of BPV1 L2 are required for BPV1 infection after the binding of the virions to the cell surface. We determined that these BPV1 L2 termini function as nuclear localization signals (NLSs). Both the N-terminal NLS (nNLS) and the C-terminal NLS (cNLS) interacted with Kap α2, formed a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers, and mediated nuclear import via a Kap α2β1 pathway. Interestingly, the cNLS was also the major DNA binding site of BPV1 L2. Consistent with the promiscuous DNA encapsidation by BPV1 pseudovirions, this DNA binding occurred without nucleotide sequence specificity. Moreover, an L2 mutant encoding a scrambled version of the cNLS, which supports production of virions, rescued the DNA binding but not the Kap α2 interaction. These data support a model in which BPV1 L2 functions as an adapter between the viral DNA via the cNLS and the Kaps via the nNLS and facilitates nuclear import of the DNA during infection.

Papillomaviruses (PVs) are nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses that specifically infect squamous epithelial cells. The icosahedral capsid comprises 72 pentamers (capsomers) of the L1 major capsid protein (3, 29). It is proposed that the L2 minor capsid protein is associated with 12 L1 capsomers on the fivefold axis of symmetry (29). L1 can self-assemble into virus-like particles and L2 is incorporated into virus-like particles when coexpressed with L1 (13, 14, 37). L1 expressed alone in mammalian cells containing episomal PV DNA forms virions (30), although L2 increases the efficiency of DNA encapsidation by at least 50 fold (24, 25, 27). The L2 protein of bovine PV type 1 (BPV1) interacts with BPV1 L1 via two domains (residues 129 to 246 and 384 to 460), and both domains are required for efficient encapsidation of the viral genome (22). L2 expressed in cultured cells localizes to the nucleus in nuclear structures known as PML oncogenic domains or nuclear domains 10 (ND10) and recruits L1 to these structures (7). Interestingly, in natural lesions, expression and nuclear import of L2 during the productive stage of viral life cycle precede the expression and nuclear translocation of L1 (9).

The L2 protein is also essential for the infectivity of virions, but its roles in the viral infection are still unclear. The L2 of human PV type 16 (HPV16) binds to cells via cell surface binding domains located at residues 13 to 31 (32) and 108 to 126 of L2 (12). HPV16 L2 also interacts with β-actin via a domain located between residues 25 to 45, and deletion of this domain strongly reduces the infectivity of pseudovirions (33). Interestingly, BPV1 pseudovirions containing wild-type L1 and derivatives of L2 lacking either the N-terminal or the C-terminal positively charged domain were noninfectious, despite efficient binding to the cell surface (23). This suggests that the two BPV1 L2 termini are required for the viral infection in a step operating after the cell surface binding of the virions (23).

HPV6b L2 contains two potential nuclear localization signals (NLSs) at the N terminus and C terminus and also a nuclear retention domain in the central portion of the protein (residues 286 to 306) (28). Interestingly, in HPV33 L2, the homologous C terminus and central domain promote nuclear localization, whereas the corresponding N terminus does not (1).

The basic paradigm for NLS-mediated nuclear import is that a protein containing an NLS interacts in the cytoplasm with an import receptor belonging to the karyopherin β/importin β (Kap β/Imp β) superfamily, is translocated through the nuclear pore complex via hydrophobic interactions of Kap β with phenylalanine-glycine-containing nucleoporins, and is finally released inside the nucleus (11, 17). Several members of the mammalian Kap β superfamily have been characterized and shown to function in nuclear import of specific cargoes. The first import receptor identified, Kap β1/Imp β, can function together with a Kap α/Imp α adapter in the nuclear import of proteins that contain classic monopartite or bipartite NLSs; without adapters in import of ribosomal proteins, core histones, and cyclin B1; or together with Imp 7 in import of histone H1. All the other Kap βs do not use adapters and bind directly to the NLS of the protein to be imported into the nucleus. Kap βs shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, bind to nucleoporins and to the GTPase Ran in its GTP-bound form. Binding of Ran-GTP to the Kap βs (Imps) causes the dissociation of the import complexes, thus releasing the cargoes inside the nucleus. The nucleotide state of Ran is regulated by cytoplasmic RanGAP and RanBP1, which accelerate GTP hydrolysis to form cytoplasmic RanGDP, and by nuclear RanGEF (RCC1) which catalyzes nucleotide exchange to generate nuclear Ran-GTP (11, 17).

In this study, we investigated the interactions of BPV1 L2 minor capsid protein with the Kaps and the DNA. We found that BPV1 L2 forms a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers via interaction with the Kap α2 adapter. BPV1 L2 does not interact with other Kap β import receptors, such as Kap β2 or Kap β3. Using deletion mutagenesis and glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins, we determined that BPV1 L2 contains two NLSs, one in the N terminus (nNLS) and the other one in the C terminus (cNLS). Both NLSs interact with the Kap α2 adapter and form a complex with Kap α2-β1 heterodimers.

Interestingly, the cNLS is also the major DNA binding site of BPV1 L2, as deletion of the cNLS abolishes the DNA binding activity of BPV1 L2 and as a GST-cNLS fusion protein is able to bind to the DNA as strongly as the wild-type L2. Moreover, an L2 derivative containing a scrambled cNLS binds the DNA as well as the wild-type L2 and rescues the infectivity but does not interact with the Kap α2 adapter. Together, these data suggest the possibility that in the initial phase of infection L2 functions as an adapter between the viral DNA and the import machinery and facilitates nuclear import of the DNA, which is essential for the viral infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of recombinant human nuclear import factors.

His-tagged Kap α2 (31) and His-tagged Kap β1 (4) were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 Star and E. coli BL21(DE3), respectively (3-h induction with 2 mM IPTG [isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside] at 30°C), and the soluble His-tagged proteins were purified in their native state on Talon beads by a standard procedure. GST-Kap β1 (4) and GST-Kap β2 (5) were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), GST-Kap β3 (34) was expressed in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (3-h induction with 1 mM IPTG at 30°C), and the soluble GST-Kap β fusion proteins were purified in their native state on glutathione-Sepharose beads by a standard procedure. Human Ran (6) was prepared as previously described (8). Ran was loaded with GTP by incubation with 100 mM GTP, 0.5 M EDTA, 1 M dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1 M HEPES (pH 7.4) for 30 min at room temperature (RT); the reaction was stopped with 1.5 M magnesium chloride (pH 7.4). All proteins were checked for purity and lack of proteolytic degradation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining. The purified proteins were dialyzed in transport buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.3], 110 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, plus protease inhibitors), and stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. HeLa cytosol from Cellex Biosciences, Inc., was centrifuged and stored in small aliquots at −80°C.

Preparation of BPV1 L2 protein and L2 derivatives.

Wild-type BPV1 L2 protein, L2Δ2-9, L2Δ461-469, the L2Δ2-9Δ461-469 double mutant, and L2mix461-469 mutant genes were excised from pSFV4.2 with EcoRI and SmaI and subcloned into the EcoRI and StuI sites of pProExHtb (Invitrogen) to include an N-terminal His tag. The constructs were expressed in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 30°C). The BPV1 L2 proteins were purified from inclusion bodies with the Novagen protein refolding kit. The bacteria were lysed by sonication in 20 mM Tris-Hcl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 100 μg of lysozyme/ml and subjected to centrifugation. The pellets containing the inclusion bodies were solubilized in 50 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) (pH 11.0) containing 0.3% N-lauroylsarcosine. Refolding of the protein was achieved by extensive dialysis against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) containing 0.1 mM DTT. Final dialysis was performed against transport buffer (pH 7.3). The His-tagged BPV1 L2 proteins were specifically bound to Talon beads via their His tag and subsequently eluted to be used in overlay blot assays.

Preparation of GST-NLS fusion proteins.

The N-terminus sequence (1MSARKRVKRA10), the C-terminus sequence (460LRKRKKRKHA469) of BPV1 L2 and the scrambled C terminus (LKRKHRARKK), all rich in positively charged amino acids, were separately fused to a GST reporter protein to obtain GST-nNLS, GST-cNLS, and GST-mixed C-terminus NLS (mixcNLS). To make the GST-NLS constructs, the corresponding forward and reverse oligonucleotides were annealed to produce a double-stranded DNA molecule with EcoRI and XhoI sticky ends and inserted directly into the pGEX4T-1 vector, which was double cut with the same enzymes. The GST-NLS constructs were transformed in XL1-Blue bacteria and confirmed by automated sequence analysis (Massachusetts General Hospital Sequencing Department). For protein expression, the GST-nNLS, GST-cNLS, and GST-mixcNLS constructs were used to transform E. coli BL21-CodonPlus. After induction of the bacteria with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37°C, the GST-NLS fusion proteins were purified in their native state on glutathione-Sepharose by a standard procedure. Note that the GST-cNLS and GST-mixcNLS were difficult to elute from the glutathione-Sepharose beads, due to a tendency to aggregate; only low concentrations of the proteins were obtained. The GST-NLSHPV16L1 containing the monopartite NLS (AKRKKRKL) of HPV16 L1 major capsid protein was prepared as previously described (21).

Antibodies.

Rabbit polyclonal antiserum was raised against BPV1 L2 as previously described (25). A mouse antibody to Kap α2/Rch1 was from Transduction Laboratories; a mouse antibody to six-His tag and a goat anti-GST antibody were from Amersham Biosciences. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and anti-goat) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Overlay blot assays.

The BPV1 L2 wild type and mutants, different GST-NLS fusion proteins, or GST (all the proteins at 2 μg/lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The proteins on the blots were stained with Ponceau, and the individual lanes were cut and then blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% nonfat milk in phosphate-buffered saline. The individual blots were then incubated with different Kaps as indicated in the figure legends. The bound His-Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody (1:1,000 dilution) and the bound GST-Kaps (Kap β1, Kap β2, or Kap β3) or GST was detected with an anti-GST antibody (1:1,000 dilution), followed by the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1,000 dilution). The signal was detected with an ECL Detection Kit (Amersham Biosciences).

In-solution binding assays.

Binding assays were performed as previously described (21). Briefly, the different GST-NLSs or GST itself immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads (2 μg of protein/10 μl of beads) was incubated under rotation for 30 min at RT with the purified Kaps in binding buffer (transport buffer containing 0.01% Tween 20) as indicated in the figure legends. The bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

In vitro nuclear import assays.

The nuclear import assays were carried out as previously described (21). Briefly, subconfluent HeLa cells, grown on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips for 24 h, were permeabilized with 70 μg of digitonin/ml for 5 min on ice and washed with transport buffer. All import reaction mixtures contained an energy-regenerating system (1 mM GTP, 1 mM ATP, 5 mM phosphocreatine, and 0.4 U of creatine phosphokinase), either HeLa cytosol or various transport factors (2 μg of Kap α2, 2 μg of Kap β1, or 3 μg of RanGDP), and the different GST-NLSs (1 μg). The final import reaction mixture volume was adjusted to 20 μl with transport buffer. For visualization of nuclear import, the GST-NLS fusion proteins were detected by immunofluorescence with an anti-GST antibody (21). The nuclei were identified by DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. Nuclear import was analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 Microscope with a fluorescence attachment and a Sony DKC-5000 CCD camera. All the pictures in an experiment were taken at the same exposure time.

DNA mobility shift assays.

DNA mobility shift assays were performed essentially as described previously (20). Proteins to be tested were incubated with the HPV16 DNA plasmid for 30 min at RT in transport buffer. GST was used as a negative control, whereas GST-NLSHPV16L1 was used as a positive control. The DNA or DNA-protein complexes were analyzed by electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose gels and ethidium bromide staining.

RESULTS

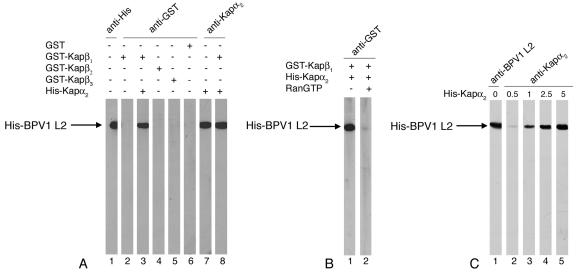

BPV1 L2 minor capsid protein forms a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers via interaction with the Kap α2 adapter. The interactions between BPV1 L2 minor capsid protein and the Kaps were investigated by overlay blot assays. The purified His-tagged BPV1 L2 was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the L2 blots were incubated with different Kaps at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. We found that Kap α2 adapter bound directly to the BPV1 L2 protein in the absence or in the presence of the Kap β1 nuclear import receptor (Fig. 1A, lanes 7 and 8). GST-Kap β1 bound to BPV1 L2 in the presence of Kap α2 adapter (Fig. 1A, lane 3) but did not in its absence (Fig. 1A, lane 2). GST, the negative control, did not interact with the BPV1 L2 protein (Fig. 1A, lane 6). Neither GST-Kap β2 nor GST-Kap β3 bound to the BPV1 L2 protein (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 5). These data suggest that BPV1 L2 minor capsid protein forms a complex with the Kap α2β1 heterodimer via interaction with the Kap α2 adapter but does not interact with either Kap β2 or Kap β3 nuclear import receptors. Moreover, RanGTP prevented formation of the L2/Kap α2β1 complex (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2), suggesting that the complex could be dissociated by nuclear RanGTP after import. Titration experiments with increasing amounts of Kap α2 showed that BPV1 L2 has high-affinity binding for the Kap α2 adapter (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

BPV1 L2 minor capsid protein forms a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimer via interaction with Kap α2 adapter, but does not interact with Kap β2 and Kap β3 nuclear import receptors. (A) BPV1 L2 blots (2 μg of protein/lane) were incubated with either GST-Kap β1 (lane 2), GST-Kap β1 plus Kap α2 (lane 3), GST-Kap β2 (lane 4), GST-Kap β3 (lane 5), or GST (lane 6), and the bound GST-Kap βs were detected with an anti-GST antibody. Two BPV1 L2 blots were incubated with Kap α2 in the absence (lane 7) or presence (lane 8) of GST-Kap β1, and the bound Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody. In lane 1, the BPV1 L2 blot was detected with an anti-His antibody. (B) BPV1 L2 blots were incubated with Kap α2 plus GST-Kap β1 in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of Ran-GTP. (C) BPV1 L2 blots (2 μg of protein/lane) were incubated with increasing concentrations of Kap α2 (from 0.5 to 5 μg/ml), and the bound Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody (lanes 2 to 5). In lane 1, the BPV1 L2 blot was detected with an anti-His antibody. All blots contained 2 μg of protein/lane.

BPV1 L2 contains two NLSs, both binding Kap α2β1 heterodimers and mediating nuclear import via a Kap α2β1 pathway.

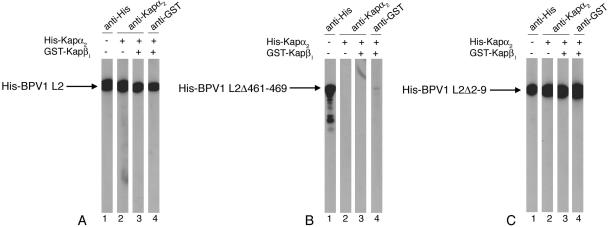

Coexpression of BPV1 L1 and L2 mutants lacking either eight N-terminal (SARKRVKR) or nine C-terminal (RKRKKRKHA) amino acids resulted in wild-type levels of viral genome encapsidation, but the resulting virions were noninfectious (23). Both these termini encode positively charged domains, which could function as NLSs in nuclear import of BPV1 L2 in vivo. We analyzed the interactions of these two BPV1 L2 deletion mutants with Kap α2 and Kap α2β1 heterodimers in comparison with the wild-type L2. We found that BPV1 L2Δ461-469 no longer interacted with Kap α2 and consequently did not form a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the BPV1 L2Δ2-9 interacted with Kap α2 and formed a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers as well as the wild-type BPV1 L2 (Fig. 2A and C). These data suggest that the positively charged C terminus is an NLS interacting with high affinity with Kap α2.

FIG. 2.

The C-terminal amino acids 461 to 469 of BPV1 L2 are required for high-affinity interaction with the Kap α2 adapter. Wild-type BPV1 L2 (A), BPV1 L2Δ461-469 (B), and BPV1 L2Δ2-9 (C) were incubated with Kap α2 in the absence (lanes 2) or presence (lanes 3 and 4) of GST-Kap β1. Bound Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody (lanes 2 and 3) and bound GST-Kap β1 was detected with an anti-GST antibody (lanes 4). In lanes 1, the BPV1 L2 proteins were detected with an anti-His antibody. All blots contained 2 μg of protein/lane.

To further analyze these interactions, we made two GST fusion proteins, GST-nNLS and GST-cNLS. We analyzed the interactions of these two GST fusion proteins with Kap α2 and Kap α2β1 heterodimers by both overlay blot assays and in-solution binding assays. GST-cNLS interacted with high affinity with Kap α2 in overlay blot assays (Fig. 3A, lanes 10 to 12). Interestingly, GST-nNLS also interacted with Kap α2 (Fig. 3A, lanes 6 to 8), although with much lower affinity than the GST-cNLS (lanes 10 to 12) or the full-length L2 protein (lanes 2 to 4). The negative Kap α2 binding results for the L2Δ461-469 which contains the nNLS could be explained by the fact that the N-terminal domain in the context of the L2 protein may not be sufficiently exposed during the overlay blot assay conditions.

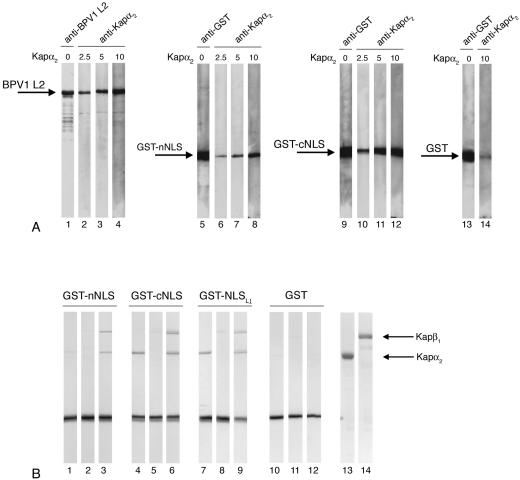

FIG. 3.

BPV1 L2 contains two NLSs in the C terminus and the N terminus, both interacting with Kap α2 and forming a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers. (A) Blots containing BPV1 L2 (lanes 2 to 4), GST-nNLS (lanes 6 to 8), or GST-cNLS (lanes 10 to 12) were incubated with increasing amounts of Kap α2 (from 2.5 to 10 μg/ml), and bound Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody. BPV1 L2 was detected with an anti-BPV1 L2 antibody (lane 1), and the GST-nNLS, GST-cNLS, and GST proteins were detected with an anti-GST antibody (lanes 5, 9, and 13, respectively). In lane 14, GST was incubated with 10 μg of Kap α2/ml, and the nonspecifically bound Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody. (B) GST-nNLS (lanes 1 to 3), GST-cNLS (lanes 4 to 6), GST-NLSHPV16L1 (lanes 7 to 9), and GST (lanes 10 to 12) immobilized on gluthatione-Sepharose (2 μg of protein/10 μl of beads) were incubated with either Kap α2 (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10), Kap β1 (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11), or Kap β1 plus Kap α2 (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12). The input of Kap α2 and Kap β1 is shown in lanes 13 and 14. Bound proteins were eluted with sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

In-solution binding assays show that both the GST-nNLS and GST-cNLS formed a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers via interaction with Kap α2 (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 6), but neither one interacted directly with the Kap β1 import receptor (lanes 2 and 5). As expected, the positive control for the classical pathway, GST-NLSHPV16L1, interacted with Kap α2 and formed a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimer (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 to 9), whereas GST, the negative control, did not (lanes 10 to 12). Together, these data suggest that the BPV1 L2 protein contains two NLSs in the N terminus and C terminus, both interacting with the Kap α2 adapter and forming a complex with the Kap α2β1 heterodimer. Moreover, RanGTP prevented formation of GST-nNLS/Kap α2β1 and GST-cNLS/Kap α2β1 complexes (data not shown), suggesting that these complexes can be dissociated by nuclear RanGTP.

We next determined whether nNLS and cNLS can independently mediate nuclear import of a GST reporter protein in digitonin-permeabilized HeLa cells via Kap α2β1 heterodimers. GST was used as a negative control, and GST-NLSHPV16L1 was used as a positive control for the classical Kap α2β1 pathway. The nNLS mediated nuclear import of the GST reporter protein in the presence of either cytosol containing the Kaps or Kap α2β1 heterodimers plus RanGDP (Fig. 4A, panels 2 and 4), but not in the presence of only transport buffer or Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 1 and 3). As expected, the GST negative control was not imported into the nucleus in the presence of either cytosol or Kap α2β1 heterodimers plus RanGDP (Fig. 4A, panels 6 and 8). The GST-cNLS had a tendency to aggregate in the cytoplasm during the import assays in the presence of either transport buffer or recombinant Kaps plus RanGDP (Fig. 4B, panels 1, 3, and 4). This may explain the reduction and variations in the Kap α2β1-mediated nuclear import of GST-cNLS in our assays (Fig. 4B, panels 2 and 4). We noticed that the GST-cNLS was imported better in the presence of exogenous cytosol than the recombinant Kap α2β1 heterodimers (Fig. 4B, panels 2 and 4), most likely due to the presence of chaperones in the cytosol preventing the aggregation of the GST-cNLS. As expected, the GST-NLSHPV16L1 positive control was imported into the nuclei in the presence of either cytosol or Kap α2β1 plus RanGDP (Fig. 4B, panels 6 to 8).

FIG. 4.

Both the nNLS and cNLS of BPV1 L2 can independently mediate nuclear import of a GST reporter via a classical Kap α2β1 pathway. (A) Digitonin-permeabilized cells were incubated with either GST-nNLS (panels 1 to 4), or GST (panels 5 to 8) in the presence of either transport buffer (panels 1 and 5), cytosol (panels 2 and 6), Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 3 and 7), or Kap α2 plus Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 4 and 8). (B) Digitonin-permeabilized cells were incubated with either GST-cNLS (panels 1 to 4), GST-NLSHPV16L1 (panels 5 to 8) in the presence of either transport buffer (panels 1 and 5), cytosol (panels 2 and 6), Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 3 and 7), or Kap α2 plus Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 4 and 8). Nuclear import of the GST-NLSs was detected with an anti-GST antibody.

BPV1 L2 minor capsid protein interacts with the viral DNA via its cNLS.

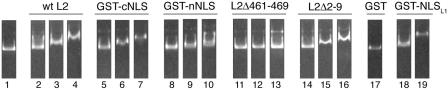

It has previously been shown that the L2 minor capsid protein of high-risk HPV16 interacts with the viral DNA in a sequence-independent manner via its positively charged N terminus (36). As it was not known if BPV1 L2 interacts with the viral DNA in a similar manner, we analyzed the interactions of the wild-type BPV1 L2 and the DNA by mobility shift assays. When the HPV16 DNA was incubated with increasing amounts of wild type BPV1 L2, there was an increased mobility shift of the DNA (Fig. 5, lanes 2 to 4), indicating that the BPV1 L2 interacted with the DNA. Analysis of the interactions of GST-cNLS and GST-nNLS with the viral DNA revealed that GST-cNLS bound to the DNA and caused a clear mobility shift (Fig. 5, lanes 5 to 7). GST-nNLS caused only a small shift at the higher protein concentration (Fig. 5, lanes 9 and 10). The L2Δ461-469 derivative, containing nNLS and not cNLS, no longer bound to the DNA (Fig. 5, lanes 11 to 13), whereas the L2Δ2-9 lacking the nNLS but with the cNLS retained the same DNA binding activity as the wild-type L2 (Fig. 5, lanes 14 to 16 versus 2 to 4). The negative control, GST, did not bind to the DNA (Fig. 5, lane 17), whereas the positive control, GST-NLSHPV16L1 did (Fig. 5, lanes 18 and 19). We also examined the interactions of BPV1 L2 and GST-cNLS with a nonviral unrelated plasmid DNA and obtained the same results (data not shown). Together, the data suggest that the BPV1 L2 protein interacts with the DNA in a sequence-nonspecific manner and that the cNLS is the high-affinity DNA binding site of BPV1 L2.

FIG. 5.

BPV1 L2 interacts with the DNA via its cNLS. HPV16 DNA plasmid (lane 1) was incubated with increasing amounts (2, 5, or 10 μg of protein) of either wild-type BPV1 L2 (lanes 2 to 4), GST-cNLS (lanes 5 to 7), GST-nNLS (lanes 8 to 10), L2Δ461-469 (lanes 11 to 13), or L2Δ2-9 (lanes 14 to 16). As controls, the DNA was incubated with 10 μg of GST (lane 17) or increasing amounts of GST-NLSHPV16L1 (lanes 18 and 19). The DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

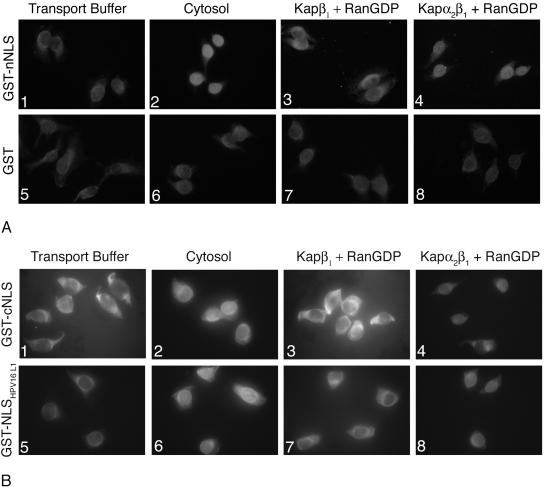

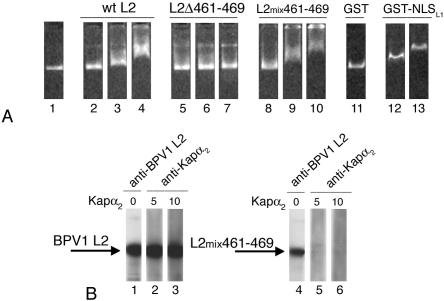

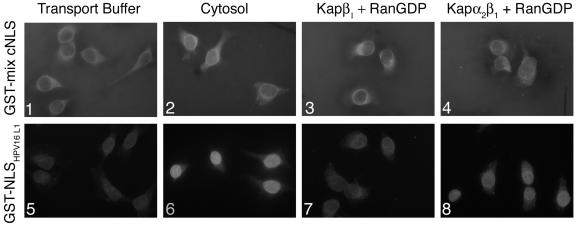

Previous data have shown that BPV1 pseudovirions containing wild type L1 and an L2 derivative in which the nine C-terminal amino acids are scrambled (L2mix461-469, which replaces RKRKKRKHA with KRKHRARKK) are equally as infectious (23). Therefore, in comparison with the noninfectious pseudovirions containing the L2Δ461-469 deletion mutant, restoration of the positive charge at the BPV1 L2 C terminus in the scrambled form restores infectivity (23). To gain more insight into the role of the C terminus in infectivity, we investigated if the L2mix461-469 is able to bind the DNA. Analysis of the interactions of wild-type L2, L2Δ461-469, and L2mix461-469 revealed that the L2mix461-469 bound to the DNA as efficiently as the wild-type L2, whereas the L2Δ461-469 did not (Fig. 6A). In contrast, we found that the L2mix461-469 did not interact with Kap α2 in an overlay blot assay, even at high concentrations of Kap α2 (Fig. 6B), similar to the L2Δ461-469 mutant (Fig. 5). These data would suggest that restoration of the positive charge at the L2 C terminus in scrambled form restores the DNA binding but not the Kap α2 interaction of the BPV1 L2 cNLS. The lack of interaction of the L2mix461-469 scrambled mutant with Kap α2 suggests that the scrambled mixcNLS would be unable to mediate nuclear import via a Kap α2β1 pathway. Therefore, we tested the scrambled mixcNLS in nuclear import assays. Digitonin-permeabilized cells were incubated with GST-mixcNLS or GST-NLSHPV16L1, as a positive control, in the presence of either transport buffer or cytosol or recombinant Kaps plus RanGDP. As expected, NLSHPV16L1 mediated nuclear import of the GST reporter in the presence of either cytosol or recombinant Kap α2β1 plus RanGDP (Fig. 7, panels 6 and 8), whereas the mixcNLS did not (Fig. 7, panels 2 and 4). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the inability of the mixcNLS to mediate nuclear import may be caused by its tendency to aggregate.

FIG. 6.

Restoration of the positive charge at the BPV1 L2 C terminus in scrambled form restores the DNA binding, but not the Kap α2 interaction. (A) HPV16 DNA plasmid (lane 1) was incubated with increasing amounts (2, 5, or 10 μg of protein) of either wild-type BPV1 L2 (lanes 2 to 4), L2Δ461-469 (lanes 5 to 7), or L2mix461-469 (lanes 8 to 10). As controls, the DNA was incubated with 10 μg of GST (lane 11) or increasing amounts of GST-NLSHPV16L1 (lanes 12 and 13). The DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining. (B) Wild-type BPV1 L2 blots (lanes 2 and 3) and L2mix461-469 blots (lanes 5 and 6) were incubated with increasing concentrations of Kap α2 (5 and 10 μg/ml), and the bound Kap α2 was detected with an anti-Kap α2 antibody. In lanes 1 and 4, the L2 blots were detected with an anti-BPV1 L2 antibody. All blots contained 2 μg of protein/lane.

FIG. 7.

The mixcNLS does not mediate nuclear import of a GST reporter protein. Digitonin-permeabilized cells were incubated with either GST-mixcNLS (panels 1 to 4) or GST-NLSHPV16L1 (panels 5 to 8) in the presence of either transport buffer (panels 1 and 5), cytosol (panels 2 and 6), Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 3 and 7), or Kap α2 plus Kap β1 plus RanGDP (panels 4 and 8). Nuclear import of the GST-NLSs was detected with an anti-GST antibody. Note the nuclear import in panels 6 and 8.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the interactions of BPV1 L2 with the nuclear import machinery and the viral DNA and mapped its NLSs and DNA binding site. BPV1 L2 forms a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers via interaction with the Kap α2 adapter. Interestingly, BPV1 L2 does not interact with either Kap β2 or Kap β3 nuclear import receptors. This is different from HPV16 L2, which in addition to forming a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers also interacts with Kap β2 and Kap β3 nuclear import receptors (7), suggesting that there are differences between the L2 proteins of different PVs regarding their nuclear import pathways.

We next determined that the positively charged BPV1 L2 termini, shown previously to be required for infection (23), function as NLSs. Both the nNLS and cNLS interact independently with Kap α2 adapter, form a complex with Kap α2β1 heterodimers, and mediate nuclear import of a GST reporter via a classical Kap α2β1 pathway (Table 1). Either NLS is functional in nuclear import of BPV1 L2 in vivo, as both the N-terminal and the C-terminal L2 deletion derivatives are localized in the nucleus similar to the wild-type L2 when the L2 proteins are expressed in cells in culture (23). The fact that BPV1 L2 has two independent NLSs suggests that one NLS is functional during the initial phase of infection after virion disassembly when L2 is transported into the nucleus (38) and that the other one is functional during the productive phase when the newly synthesized L2 together with L1 assembles the replicated viral DNA in the nucleus into virions. However, deletion of either NLS has no effect upon genome encapsidation, suggesting that they are redundant during virion morphogenesis (23). Both NLSs are required for infectivity (23), suggesting that they perform independent but complementary functions during infection.

TABLE 1.

The functions of the two NLSs of BPV1 L2

| NLS type | Binding Kap α2β1 | Nuclear import | Binding DNA | Required for infectivity(23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nNLS | + | + | − | + |

| cNLS | + | + | + | + |

| mixcNLS | − | − | + | + |

Interestingly, we discovered that the cNLS is also the major DNA binding site of BPV1 L2 (Table 1). Furthermore, L2 dramatically enhances genome encapsidation, yet deletion of the cNLS of L2 has no effect upon this process (23). This is consistent with the finding that the DNA binding domain of L1 is critical for genome encapsidation (26) and implies that L2 has functions distinct from DNA binding during virion assembly. These functions may relate to the localization of L2 in PML oncogenic domains or ND10 with Daxx (7, 10). The DNA binding activity of L2 is nucleotide sequence independent. This is consistent both with the promiscuous packaging of DNA by BPV1 pseudovirions (2, 35) and with a central role for the DNA binding domain of L1 in genome encapsidation (26). The DNA binding domain of VP1 of simian virus 40 (SV40) performs a similar function (15).

Although the BPV1 L2 cNLS is dispensable for genome encapsidation, it is critical for infection (23). Therefore, the question arose as to what role BPV1 L2 cNLS fulfills during infection: binding to the viral DNA or nuclear import of L2? To address this question, we tested an L2 mutant encoding a scrambled version of the cNLS, which supports the production of infectious virions (23). We found that this L2 mutation rescued the DNA binding but not the Kap α2 interaction that mediates nuclear import (Table 1). This suggests that restoration of the positive charge at the C terminus rescues the nucleotide sequence-independent DNA binding activity of L2 and indicates that the amino acid order in this highly positively charged region is not critical. As this C-terminal scrambled L2 protein restores infectivity (23) but not the interaction with the import machinery and consequently nuclear import, this would suggest that the role of the BPV1 L2 cNLS in infectivity may be limited to its interaction with the viral genomic DNA. Based on these biochemical data, we propose a model in which L2 functions as an adapter between the viral DNA and the Kaps and thereby mediates transport of the DNA into the nucleus to complete infection. BPV1 L2 would bind the Kap α2β1 heterodimers via its nNLS and the viral DNA via its cNLS. Recent confocal microscopy data were presented by Day and coworkers at the 2004 Molecular Biology of DNA Tumor Viruses Conference, held 13-18 July at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, showing colocalization of BPV1 L2 and encapsidated DNA in the nucleus at ND10 after L1/L2 pseudovirion infection of HeLa cells. Moreover, when pseudovirions containing either L2Δ2-9 or the L2Δ461-469 mutant were used, the viral DNA could not escape the late endosomal compartment, suggesting that the L2 protein is required for nuclear localization of the viral genome and that the N- and C-termini of L2 play a critical role in this process (John Schiller, personal communication).

Although the virion is too large to pass through a nuclear pore (16, 20, 21), it is unclear whether L1 capsomers or monomers also enter the nucleus associated with the L2-DNA complex during infection. However, the L1 major capsid protein is unlikely to function alone as an adapter between the viral DNA and the Kaps, as it contains only one NLS, which overlaps with the DNA binding site (20). In the structurally and functionally related virus SV40, nuclear import of SV40 DNA is mediated by the VP3 capsid protein via interaction with the Imp α2β heterodimer (19). Furthermore, SV40 VP3 but not VP1 enters the nucleus with the viral genome to mediate infection (18), suggesting by analogy that L2 alone delivers the viral genome to the nucleus after PV disassembly.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Blobel, Y. M. Chook, S. Adam, K. Weis, A. Lamond, G. Dreyfuss, and N. Yaseen for their generous gifts of expression vectors. We thank Carrie Charlton, Sophie Forte, Jennifer Bordeaux, and James Daley for technical assistance in preparation of recombinant transport factors and GST-NLS fusion proteins. We thank C. Hoffman for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1-RO1 CA94898-01) to J.M. and a Research Scholar Grant to R.B.S.R. from the American Cancer Society (RSG-02-175-01-MBC).

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker, K. A., L. Florin, C. Sapp, and M. Sapp. 2003. Dissection of human papillomavirus type 33 L2 domains involved in nuclear domains (ND) 10 homing and reorganization. Virology 314:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck, C. B., D. V. Pastrana, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 2004. Efficient intracellular assembly of papillomaviral vectors. J. Virol. 78:751-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, X. S., R. L. Garcea, I. Goldberg, G. Casini, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of small virus-like particles assembled from the L1 protein of human papillomavirus 16. Mol. Cell 5:557-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi, N. C., E. J. Adam, G. D. Visser, and S. A. Adam. 1996. RanBP1 stabilizes the interaction of Ran with p97 nuclear protein import. J. Cell Biol. 135:559-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chook, Y. M., and G. Blobel. 1999. Structure of the nuclear transport complex karyopherin-beta2-Ran x GppNHp. Nature 399:230-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutavas, E., M. Ren, J. D. Oppenheim, P. D'Eustachio, and M. G. Rush. 1993. Characterization of proteins that interact with the cell-cycle regulatory protein Ran/TC4. Nature 366:585-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darshan, M. S., J. Lucchi, E. Harding, and J. Moroianu. 2004. The L2 minor capsid protein of human papillomavirus type 16 interacts with a network of nuclear import receptors. J. Virol. 78:12179-12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Day, P. M., R. B. Roden, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1998. The papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, induces localization of the major capsid protein, L1, and the viral transcription/replication protein, E2, to PML oncogenic domains. J. Virol. 72:142-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Floer, M., and G. Blobel. 1996. The nuclear transport factor karyopherin beta binds stoichiometrically to Ran-GTP and inhibits the Ran GTPase activating protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:5313-5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Florin, L., C. Sapp, R. E. Streeck, and M. Sapp. 2002. Assembly and translocation of papillomavirus capsid proteins. J. Virol. 76:10009-10014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Florin, L., F. Schafer, K. Sotlar, R. E. Streeck, and M. Sapp. 2002. Reorganization of nuclear domain 10 induced by papillomavirus capsid protein l2. Virology 295:97-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried, H., and U. Kutay. 2003. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: taking an inventory. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60:1659-1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawana, Y., K. Kawana, H. Yoshikawa, Y. Taketani, K. Yoshiike, and T. Kanda. 2001. Human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid protein L2 N-terminal region containing a common neutralization epitope binds to the cell surface and enters the cytoplasm. J. Virol. 75:2331-2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirnbauer, R., F. Booy, N. Cheng, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1992. Papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:12180-12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirnbauer, R., J. Taub, H. Greenstone, R. Roden, M. Durst, L. Gissmann, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1993. Efficient self-assembly of human papillomavirus type 16 L1 and L1-L2 into virus-like particles. J. Virol. 67:6929-6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, D. Shum, P. C. Sun, A. M. Salazar, C. F. Fernandez, S. W. Chan, and H. Kasamatsu. 2001. Simian virus 40 Vp1 DNA-binding domain is functionally separable from the overlapping nuclear localization signal and is required for effective virion formation and full viability. J. Virol. 75:7321-7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merle, E., R. C. Rose, L. LeRoux, and J. Moroianu. 1999. Nuclear import of HPV11 L1 capsid protein is mediated by karyopherin alpha2beta1 heterodimers. J. Cell. Biochem. 74:628-637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moroianu, J. 1999. Nuclear import and export pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 75(Suppl. S32):76-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakanishi, A., J. Clever, M. Yamada, P. P. Li, and H. Kasamatsu. 1996. Association with capsid proteins promotes nuclear targeting of simian virus 40 DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:96-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi, A., D. Shum, H. Morioka, E. Otsuka, and H. Kasamatsu. 2002. Interaction of the Vp3 nuclear localization signal with the importin alpha 2/beta heterodimer directs nuclear entry of infecting simian virus 40. J. Virol. 76:9368-9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson, L. M., R. C. Rose, L. LeRoux, C. Lane, K. Bruya, and J. Moroianu. 2000. Nuclear import and DNA binding of human papillomavirus type 45 L1 capsid protein. J. Cell. Biochem. 79:225-238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson, L. M., R. C. Rose, and J. Moroianu. 2002. Nuclear import strategies of high risk HPV16 L1 major capsid protein. J. Biol. Chem. 23:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okun, M. M., P. M. Day, H. L. Greenstone, F. P. Booy, D. R. Lowy, J. T. Schiller, and R. B. Roden. 2001. L1 interaction domains of papillomavirus l2 necessary for viral genome encapsidation. J. Virol. 75:4332-4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roden, R. B., P. M. Day, B. K. Bronzo, W. H. Yutzy IV, Y. Yang, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 2001. Positively charged termini of the L2 minor capsid protein are necessary for papillomavirus infection. J. Virol. 75:10493-10497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roden, R. B., H. L. Greenstone, R. Kirnbauer, F. P. Booy, J. Jessie, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1996. In vitro generation and type-specific neutralization of a human papillomavirus type 16 virion pseudotype. J. Virol. 70:5875-5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roden, R. B., R. Kirnbauer, A. B. Jenson, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1994. Interaction of papillomaviruses with the cell surface. J. Virol. 68:7260-7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafer, F., L. Florin, and M. Sapp. 2002. DNA binding of L1 is required for human papillomavirus morphogenesis in vivo. Virology 295:172-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stauffer, Y., K. Raj, K. Masternak, and P. Beard. 1998. Infectious human papillomavirus type 18 pseudovirions. J. Mol. Biol. 283:529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun, X. Y., I. Frazer, M. Muller, L. Gissmann, and J. Zhou. 1995. Sequences required for the nuclear targeting and accumulation of human papillomavirus type 6B L2 protein. Virology 213:321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trus, B. L., R. B. Roden, H. L. Greenstone, M. Vrhel, J. T. Schiller, and F. P. Booy. 1997. Novel structural features of bovine papillomavirus capsid revealed by a three-dimensional reconstruction to 9 A resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unckell, F., R. E. Streeck, and M. Sapp. 1997. Generation and neutralization of pseudovirions of human papillomavirus type 33. J. Virol. 71:2934-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weis, K., I. W. Mattaj, and A. I. Lamond. 1995. Identification of hSRP1 alpha as a functional receptor for nuclear localization sequences. Science 268:1049-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, R., P. M. Day, W. H.Yutzy IV, K.-Y. Lin, C.-F. Hung, and R. B. Roden. 2003. Cell surface-binding motifs of L2 that facilitate papillomavirus infection. J. Virol. 77:3531-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, R., W. H. Yutzy IV, R. P. Viscidi, and R. B. Roden. 2003. Interaction of L2 with β-actin directs intracellular transport of papillomavirus and infection. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12546-12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yaseen, N. R., and G. Blobel. 1997. Cloning and characterization of human karyopherin β3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4451-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao, K. N., and I. H. Frazer. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is permissive for replication of bovine papillomavirus type 1. J. Virol. 76:12265-12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou, J., X. Y. Sun, K. Louis, and I. H. Frazer. 1994. Interaction of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 capsid proteins with HPV DNA requires an intact L2 N-terminal sequence. J. Virol. 68:619-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, J., X. Y. Sun, D. J. Stenzel, and I. H. Frazer. 1991. Expression of vaccinia recombinant HPV 16 L1 and L2 ORF proteins in epithelial cells is sufficient for assembly of HPV virion-like particles. Virology 185:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, J., L. Gissmann, H. Zentgraf, H. Muller, M. Picken, and M. Muller. 1995. Early phase in the infection of cultured cells with papillomavirus virions. Virology 214:137-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]