Abstract

Objective. To create an elective course to foster student interest in pursuing a career in academic pharmacy.

Design. The course met for two hours once weekly throughout the semester and required student attendance at the AACP Annual Meeting. The course included didactic instruction, a student-designed individual teaching seminar, design and implementation of a research project for presentation at a national meeting, and drafting of a manuscript suitable for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Assessment. Student evaluations revealed strong agreement that the course met the stated objectives. Follow-up correspondence indicated that almost 70% were likely to pursue an academic career and felt the course gave them advantages over their peers in this regard.

Conclusion. The outcomes from this elective course and follow-up surveys confirmed that the majority of participants were planning on pursuing an academic pharmacy career and felt the course increased their readiness to do so.

Keywords: academic pharmacy, elective courses, student training, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

In 2002, a survey by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) found that there was a “severe shortage” in pharmacy program faculty members.1 Among the 67 programs responding to the survey, there was an average of six vacant teaching positions per program, with most (94.3%) of the vacancies being for full-time teaching positions. The majority (53.5%) of vacant positions were for pharmacy practice faculty members. These findings led the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education (AFPE) to start a $12 million campaign entitled “Investing in the Future of Pharmacy Education” to address the national pharmacy faculty shortage.1 Other initiatives to increase interest in academic pharmacy careers followed, including the launch of the Walmart Scholars Program in 2005 and efforts by the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists to promote academic careers in the pharmaceutical sciences.2

Due to projections for new school openings and faculty retirements, in 2007 AFPE predicted that the faculty shortage would grow to 9.5 vacant teaching positions per program by 2010 and 18.5 vacant teaching positions per program by 2015.3 While those draconian projections did not materialize, an ongoing shortage of pharmacy faculty remains, with the most recent data from AACP indicating an average of 3.9 vacant teaching positions per program during the 2014-2015 academic year.4 While previous efforts at addressing the pharmacy faculty shortage appear to have been successful (though correlation is not evidence of causation), additional efforts to not only foster pharmacy students’ interest in careers in academic pharmacy but also develop in them the skills necessary for success within academic pharmacy would benefit students as well as pharmacy programs and AACP as a whole.

The recruitment of future faculty members is important to combat current and future faculty shortages, as shortages create a more stressful environment for existing faculty members, particularly those in pharmacy practice disciplines.5 An average of three pharmacy practice members per pharmacy program resign annually;6 faculty shortages can produce increased workloads and create an environment where faculty burnout is a common cause of faculty attrition.7 Due (in part) to the faculty shortage, pharmacy practice department chairs use an average of 7.5 adjunct faculty members to teach required or elective courses.8 However, less than 10% of adjunct faculty members at pharmacy programs are provided a teaching mentor, leading to questions about the preparedness of adjunct faculty to teach.8 The recruitment of future pharmacists is vital to maintaining the high standards of pharmacy education, especially considering the expansion of existing pharmacy programs and implementation of new programs.

While AACP has been trying to address this problem globally for at least the last 10 years, strong arguments can be made that some of the most effective actions that can be done are at the local level, at each college, or even by individual faculty members.9 In 2005, Rodney Carter, the Chair of the Council of Faculties, challenged every faculty member to plant the faculty seed in the minds of pharmacy students to help encourage careers in academia.9

To expose students to a career in academic pharmacy, a three-hour elective course titled Academic Pharmacy was developed at the Western New England University College of Pharmacy. The course incorporates four distinct components of a pharmacy educator’s responsibilities: instruction into best practices in teaching and learning; recognition of pharmacy accreditation requirements and standards; development and execution of a scholarly research project; and interacting with faculty members and administrators at professional meetings (specifically the AACP Annual Meeting). The purpose of the course was to foster interest in careers in academic pharmacy, provide students an in-depth experience of the aspects of faculty life, and develop their skills so that they would become competitive candidates for entry-level faculty openings. To prepare this manuscript, the instructors received approval from the Western New England University Institutional Review Board (IRB) after acquiring informed consent from each student to potentially publish course evaluation data and reflective writing assignments.

DESIGN

The Academic Pharmacy course capitalized on the divergent skill and resource sets of the two instructors (an assistant dean/pharmacist and an assistant professor/pharmaceutical scientist) to provide students with a top to bottom review of academic pharmacy and the career opportunities therein. The course was offered as an elective to second professional year (P2) students. It was the only course in the college that required permission of the course instructors to enroll. To be eligible for enrollment, a student had to be in good academic standing with the college of pharmacy, demonstrate their interest in pursuing a career in academic pharmacy during an interview with one of the course instructors, and be considered by the course instructors to have the academic capabilities to successfully complete all requirements of the course. To ensure each student received the individual mentoring the authors deemed necessary to meet the course objectives by learners, course enrollment was capped at 12 students per semester.

The course was scheduled to meet for two hours once weekly throughout the semester (worth two semester credit hours), with required travel and attendance at the AACP Annual Meeting during summer recess (worth an additional semester credit hour). All class meetings were discussion-based sessions based on the assigned readings and built on previous class discussions. PowerPoint-based presentations were generally eschewed but were used by several guest presenters to deliver content and to serve as a resource.

Textbook requirements for the course were limited to those providing content on the history of pharmacy education10 and best practices in teaching pedagogy11; additional instructional materials consisted of the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education accreditation standards,12 six selected readings from the Journal covering a variety of contemporary topics affecting academic pharmacy,13-18 as well as the most-recent version of the AACP Profile of Pharmacy Faculty.19

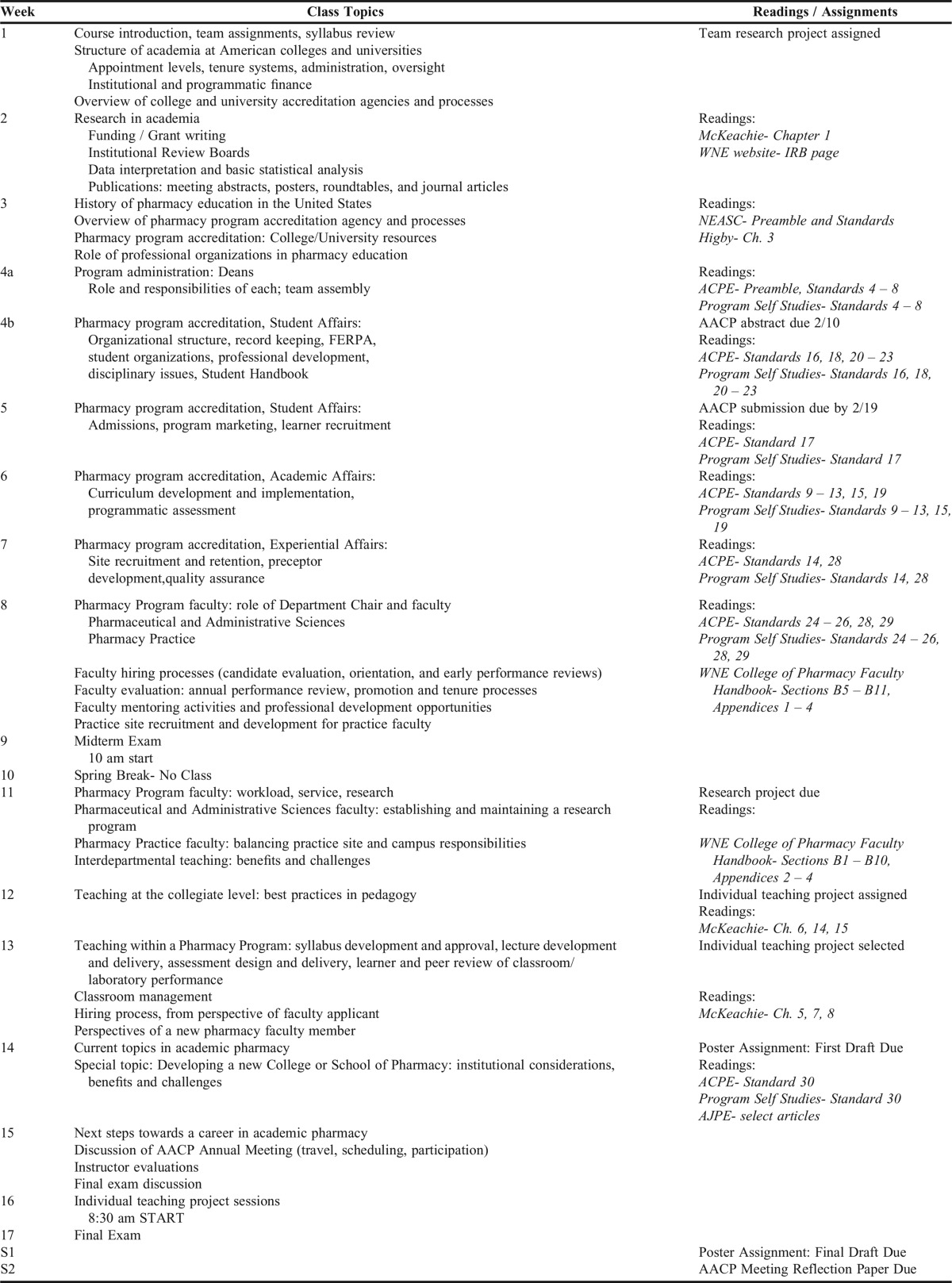

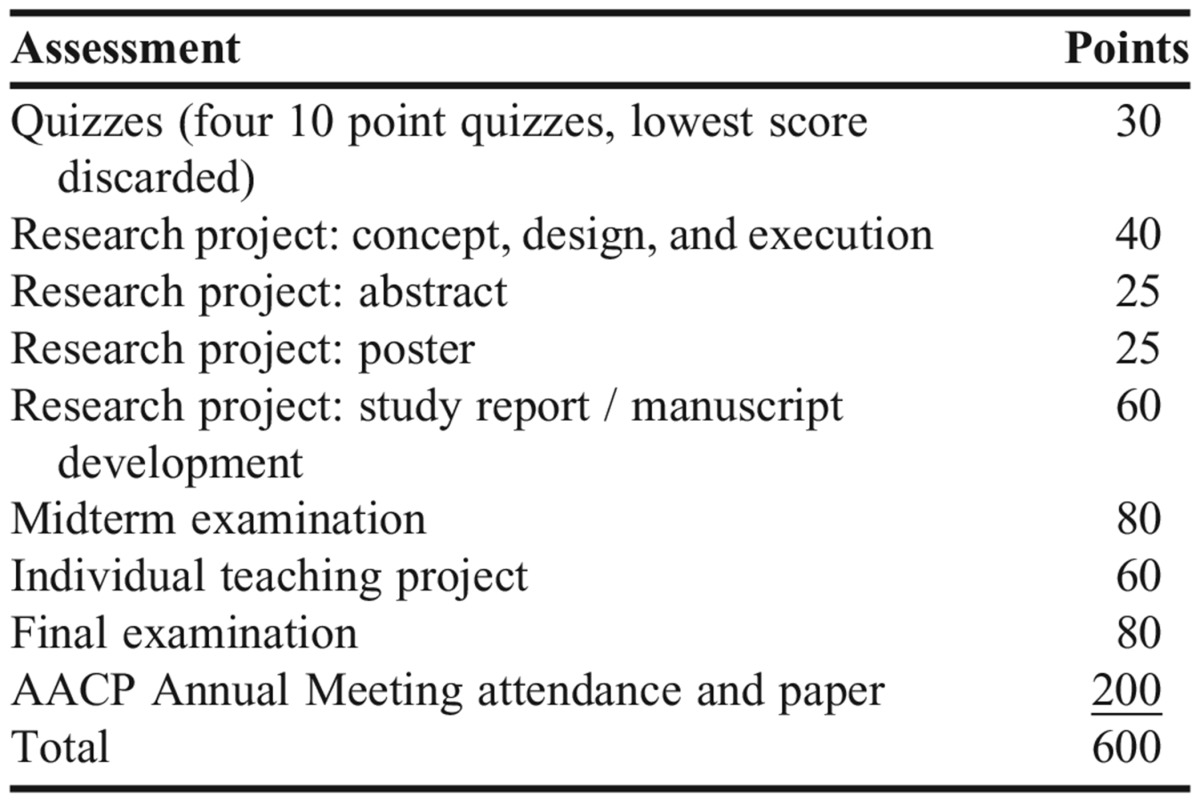

The assessment techniques and grading policy used within this course are presented in Table 1. Quizzes and examinations were used to assess student understanding of didactic instruction and required readings. The course outline can be found in Appendix I.

Table 1.

Course Assessment Techniques and Grading Policy

Because of the deadline (mid-February) for submitting an abstract to the AACP Annual Meeting, students could not afford to wait until the start of the spring semester in mid-January to commence work on their research project for the course. Thus, once students enrolled in the course in November, they met with the instructors prior to winter recess to initiate discussions on the research project they would be working on throughout the course. During this meeting, students were placed into two-person teams, potential research topics relevant to academic pharmacy were offered and considered, basic research and survey methodology was reviewed, and key upcoming deadlines (university IRB submission deadlines, research topic selection deadline, and AACP abstract submission deadline) were provided. The purpose of this meeting was to encourage students to identify their research topic and develop their strategy and tools for completing their objectives (including performance of literature reviews and development of a survey instrument) prior to the start of the spring semester. The course instructors were available over the winter recess (via e-mail, telephone, or scheduled office visit) to answer questions and provide guidance.

Following the selection of research topics, each team was assigned to one of the course instructors (who served as the primary research adviser). Under the guidance of the primary research adviser, the student team developed the methods to test their hypothesis, which was usually (but not exclusively) through the use of a survey instrument. Generally, the research team then tested the survey instrument, identified the target audience for the survey, and prepared the research proposal for submission to the university’s IRB. These steps were guided by an early semester class session devoted to the performance of research in academia, with emphasis on grant writing, IRB processes, basic statistical analyses, and publication opportunities and requirements. Following IRB approval, the survey was distributed to the target audience, and data collection began. After an appropriate number of attempts to engage the target audience and collect data, the data were aggregated, made anonymous, and statistically analyzed. A 250-word abstract formatted for submission to the AACP Annual Meeting was drafted by each student team and revised with the assistance of the instructors prior to submission.

Following abstract submission, each student team was required to craft a report of their research findings in a manuscript that followed the conventions for peer-reviewed health care literature (introduction, methods, results, discussion, references, tables, and figures). Students received an initial grade on their manuscript and feedback from both instructors, and were then given up to two opportunities to improve their study report/manuscript development score by addressing instructor feedback and making other improvements to the manuscript in subsequent revisions. For research that was deemed by the instructors to be meritorious of submission to a peer-reviewed journal, these draft manuscripts served as the basis of future submissions.

Last, the student teams developed a poster suitable for presentation at a regional or national professional pharmacy meeting. Learner teams whose abstracts were accepted for presentation at the AACP Annual Meeting presented their research and findings at the Meeting’s designated poster session. Students were given general instruction in poster development (content, graphics, layout, and production), and provided several poster templates endorsed by the college to select from. If the abstract was not accepted for presentation at the AACP Annual Meeting (to date, all abstract submissions have been accepted), the abstract had to be modified and submitted to an alternate regional or national meeting and presented at that meeting when accepted for presentation.

At the beginning of the semester, following an introduction and general overview of the course, the course began with two class sessions designed to provide students with an overview of the structure of academia at US colleges and universities. The first session presented and reviewed topics such as academic hierarchy and appointment levels, responsibilities of executive administrators (eg, board of trustees, institution president/chancellor, and select vice presidents), tenure systems, institutional finance, institutional and programmatic accreditation processes and requirements, and the role of government in postsecondary education. This information provided foundational knowledge for learners to visualize “big picture” issues as we began with a broad discussion of the history of pharmacy education in the United States, pharmacy program hierarchy, programmatic finance, and pharmacy program accreditation and oversight.

Following the broad overview of pharmacy education, a series of six class meetings were devoted to reviewing the roles and responsibilities of the pharmacy program leadership team (dean; assistant/associate deans of academic affairs, student affairs, experiential affairs; department chairs; and director of admissions). During these class meetings, the respective member of the leadership team was invited to join the class and lead a discussion on their role and responsibilities within the pharmacy program. Prior to each of these class meetings, students were assigned readings of the ACPE accreditation standards under the purview of the guest presenter; the guest presenter then walked the class through the requirements of each standard, and spoke to how the college made efforts to fulfill the requirements. Specific topics to be covered by each guest presenter were listed in the course syllabus. Role-playing exercises were used (eg, participation in a mock admissions committee meeting) to enhance student understanding. In addition, the department chairs participated in an instructor-facilitated question-and-answer session with the students, discussing in detail the faculty-hiring process (necessary qualifications, interview processes, and timelines) and the key attributes of the faculty candidates they were seeking.

Following the midterm examination, the course transitioned from an administrator-centric focus to a faculty-centric focus. One faculty representative from each department (pharmacy practice, pharmaceutical and administrative sciences) joined the class for a discussion on their role and responsibility as a faculty member. Time was devoted to discussing the competing demands of teaching, research, and service (and practice site service for clinical faculty members), establishing and sustaining a research program, maintaining the annual activity report, and preparing for the promotion and tenure review process. Expectations for teaching within a pharmacy program and classroom management techniques were reviewed (described below). At a later class session, a newly hired faculty member (usually a clinical faculty member within his/her first year of service) was invited to discuss the hiring process from his/her perspective, and shared his/her thoughts on the transition from a student to a resident to a faculty member.

As students enrolled in the course were potential future faculty members, the course instructors felt it was imperative to provide instruction on the best practices in teaching pedagogy and lecture content delivery. The director of the Western New England University Center of Teaching and Learning was invited to speak with students on content delivery methods and active-learning techniques to increase student engagement. The course instructors described the advantages and disadvantages of content delivery methods such as lectures, discussion-based learning, case-based learning, and problem-based learning. Students were also exposed to an evidence-based discussion on assessment and assessment development, including the goals of assessment, the importance of tying lecture content and assigned readings to course objectives, and a review of the strengths and weaknesses of multiple-choice questions, multiple-select questions, true/false questions, short-answer questions, and essay questions. The purpose and nature of student and peer course and instructor evaluations were discussed, and actual (unedited) student instructor evaluations for one of the authors (from a course taught to the same students earlier in the curriculum) were shared. Classroom and course management techniques for dealing with nonparticipatory audiences, over-participatory students, late arrivals, “grade grabbers,” and disruptive students were reviewed.

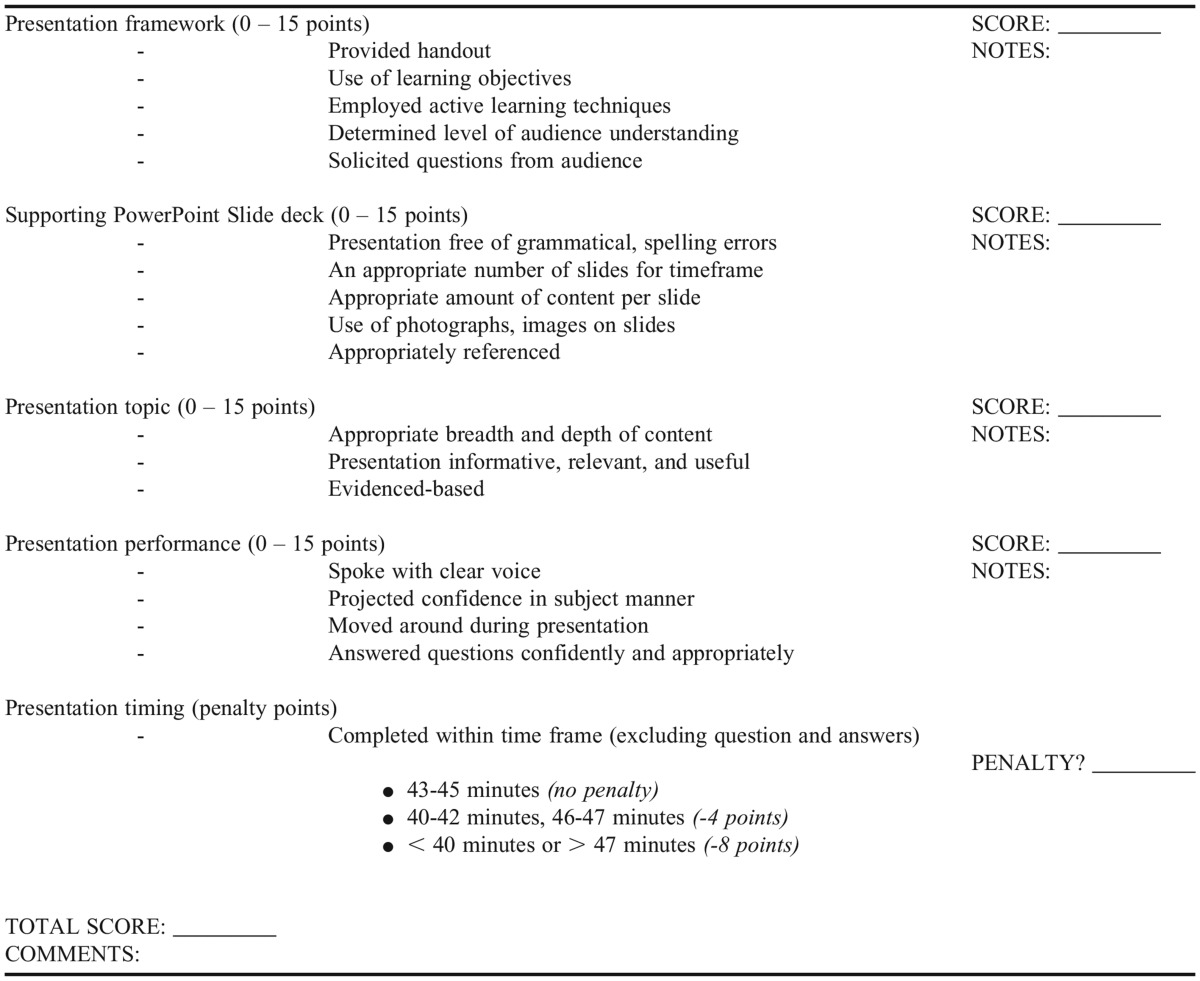

To provide the students with an opportunity to apply the content they learned about pedagogy and active learning, students were assigned to perform an individual teaching project. Students each selected a pharmacy- or medicine-related topic of his/her own choosing and developed a 45-minute presentation in the format of a faculty candidate presentation, which is typically delivered by an individual seeking an entry-level academic position. The presentations required that the student prepare a fully referenced PowerPoint® slide deck. Each instructor evaluated half of the students in the class, and the presentations also were observed (and peer evaluations provided) by other students in the course. Additionally, other pharmacy faculty members attended student presentations based upon their interest in the presentation topic. Verbal and written feedback was provided to the presenter on both the positive attributes of the presentation and items to consider for future improvement. The grading rubric for the individual teaching project can be found in Appendix II.

The capstone of the course was student attendance at the AACP Annual Meeting. Following enrollment in the course, a budget was developed by the instructors that estimated the cost of student attendance at the Annual Meeting (including AACP membership, meeting registration, lodging at the convention hotel, some meals, ground transportation to/from the airport in the host city, and poster production; airfare was excluded from the estimate because of the variety of student departure points during the summer). These estimated costs were calculated on a per student basis, rounded up to the nearest $50 increment, and charged to the student’s spring semester tuition bill as a supplemental tuition charge. By defining these costs as supplemental tuition, they could be covered under the student’s loan package as part of the total cost of attendance. An expense account was established through the university to which course-related expenses could be allocated.

At the last scheduled class session in the spring semester, a discussion was held to outline the college’s expectations of learners at the Annual Meeting, covering arrival time, attire, attitude, and attendance. Emails sent to students one month and one week prior to the start of the meeting reinforced these expectations.

While the students did spend a majority of their time attending programming at the meeting, there were numerous social opportunities for the students to interact with each other, the instructors, other administrators and faculty from our institution, and meeting attendees from other institutions. In both years, the course instructors joined all of the students for dinner on one evening, went to a baseball game with most of the students another evening, and sat with the students at the closing banquet.

Following the AACP Annual Meeting, learners have one week to compose a multi-part paper regarding their impressions of the meeting, including key areas of learning, reviews of presentations/workshops of interest, a description of their experience as a poster presenter, interactions with administrators, faculty members, and/or students of other pharmacy programs, meeting likes and dislikes, and a description on how (if at all) the meeting influenced their aspirations for pursuing a career in academic pharmacy.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Throughout the course, four low-stakes quizzes were administered to assess learning. These quizzes were based upon the content of the previous class meeting and/or the readings for that day’s class, and consisted of a combination of multiple-choice, free response, fill in the blank, and/or true/false questions. Quizzes had a maximum of five questions and were designed to be completed in five minutes. Following correction by the instructors, the quiz (questions, answers given, and correct answers) was returned to students.

Two examinations (a midterm examination and a noncumulative final examination) provided learners with summative assessment. As with quizzes, examinations consisted of a combination of multiple-choice, free response, fill in the blank, and/or true/false questions. Previously used quiz questions with a correct answer rate of 66% or less were eligible to be included in the examination. Examinations ranged between 35 and 42 questions and were designed to be completed in 60 minutes. Students were granted the opportunity to review the examination with the instructors during office hours.

A grading rubric (Appendix II) was developed by the instructors to assess student performance in the individual teaching project. The rubric was provided to students at the time the assignment was given to allow them to see how they were going to be assessed and guide the development of their presentation.

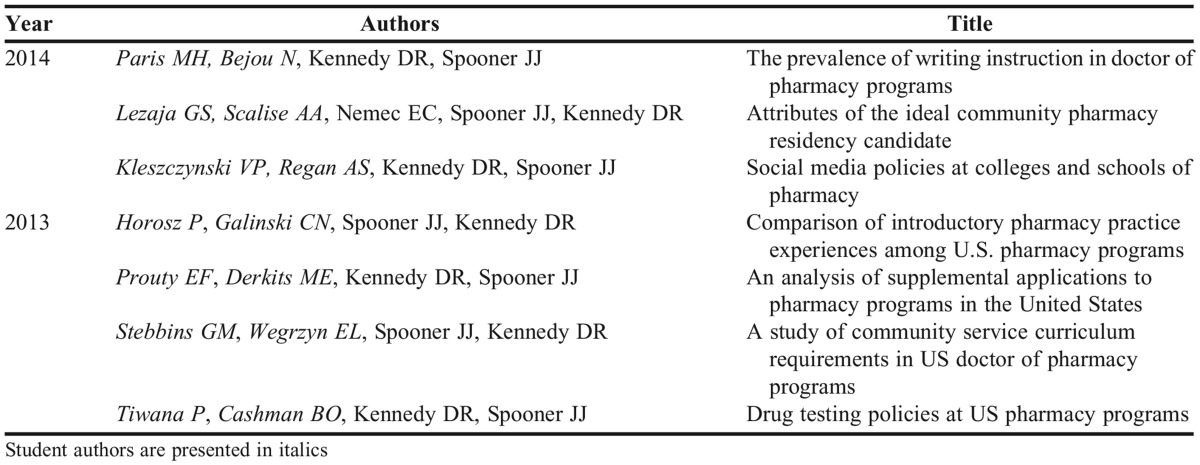

We used several methods to demonstrate student learning and success in this course. Throughout the first two offerings of the course, seven teams of two students paired with the course instructors to conduct research and submit abstracts for consideration at the AACP Annual Meeting. All seven submissions were accepted for presentation (100%) exceeding the overall abstract acceptance rate at these meetings.20,21 Accepted abstracts titles and student authors are listed in Appendix III and the complete abstracts are available in references 22 & 23.

Of the seven research projects, three met the course instructors’ criteria for robustness of the survey response rate and the importance/potential impact of the research findings to pursue publication within a peer-reviewed journal. (The four research projects that did not continue on to journal submission failed to progress because of a survey response rate below 70% [n=3] or a data collection rate below 50% [n=1].) Students served as the first and second authors on the manuscripts, participated in the selection of the target journal, and used the previously developed manuscripts to draft an initial submission that met the requirements of the journal. Students participated in the evaluation and revision and resubmission of the manuscripts following peer review comments.

Of the three manuscripts: research examining national trends in the structure of introductory pharmacy practice experiences was published in the November 2014 issue of the Journal.24 A second manuscript describing research attempting to determine the ideal attributes of candidates for community pharmacy residency programs was published in the November-December 2016 issue of Journal of the American Pharmacists Association.25 The remaining manuscript on the prevalence and nature of community service requirements in US doctor of pharmacy programs was submitted for peer review to the Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement but not accepted.

Four participants in the course submitted applications for the Walmart Scholars program, a nationally competitive scholarship program for individuals who aspire to become faculty members at pharmacy programs. Selection as a Walmart Scholar provides $1,000 to support a student’s travel and registration costs to the AACP Annual Meeting and Teachers Seminar (a day-long program preceding the Annual Meeting). Two of our applicants were selected in 2013 and a third student who applied was selected in 2015.

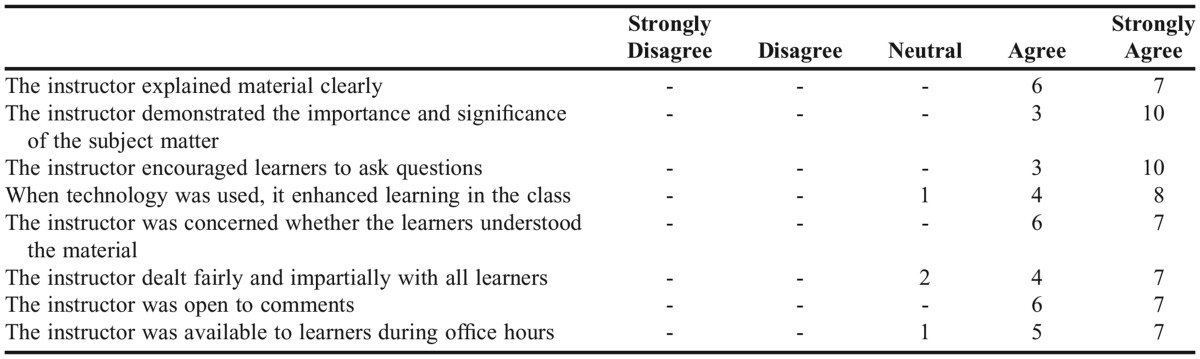

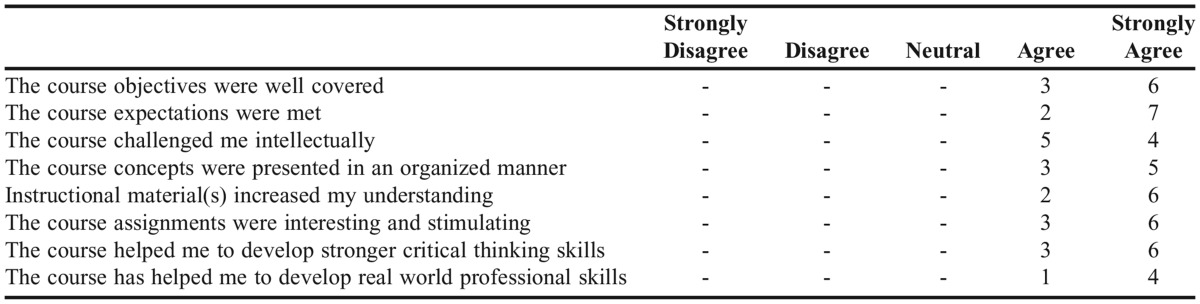

Three different methods were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the course: the regular student course and instructor evaluations done in every course at the university; student reflections at the end of the course; and a follow-up student survey one or two years after course completion to inquire about the effect of the course on their future career plans. All of these evaluations were anonymous. Learners were asked to evaluate each question on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. The aggregate instructor evaluation data are shown in Table 3, while the aggregate course evaluation data are shown in Table 4. The mean scores for each question ranged from 4.5 to 4.8, indicating a high degree of agreement. The course and instructor evaluative comments associated with these evaluations were also overwhelmingly positive.

Table 3.

Aggregate Instructor Evaluation Data

Table 4.

Aggregate Course Evaluation Data

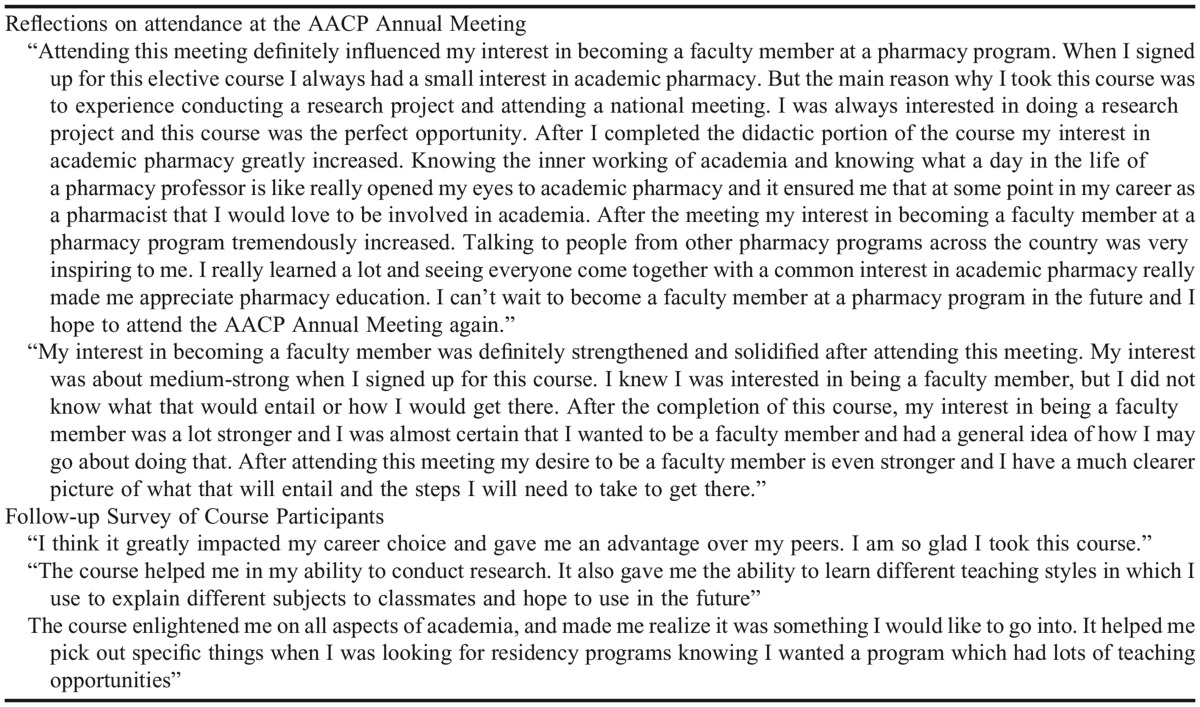

The impact and effectiveness of the course was also demonstrated in the reflections that the students wrote following their attendance at the AACP Annual Meeting. Having the ability to attend the AACP Annual Meeting and present their work at it seemed to make a strong impression on the students, as evidenced by their writing reflections. The reflections cited the interactions and encouragement that the students had with the academic pharmacy community at the AACP Annual Meeting, and how it positively impacted their desire to pursue a career in academic pharmacy. Excerpts from the student reflections can be found in Appendix IV.

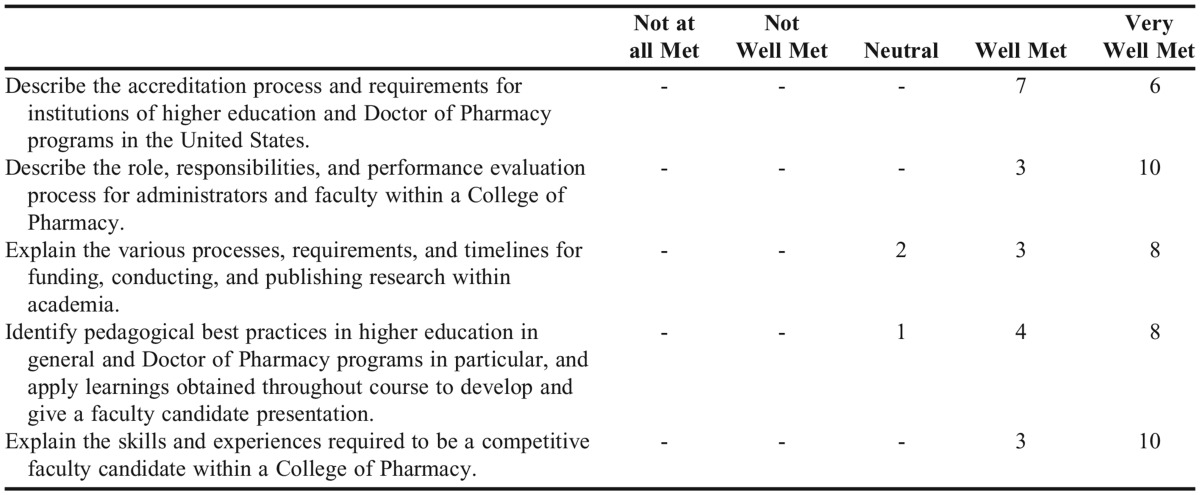

Finally, a follow-up student survey was conducted one or two years following course completion to inquire about the effect of the course on their future career plans as the students got closer to graduation. Questions asked the students to examine how well each of the course objectives were covered, how likely they were to pursue a career in academic pharmacy and then finally if there were any additional beneficial outcomes of taking the course. The student rankings of how well they felt the course objectives were met are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Student Rankings of Meeting Course Objectives (N=13)

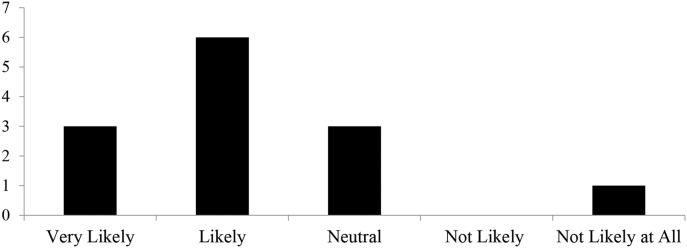

Almost 70% of the students we were able to follow-up with (13/14) were either likely or very likely to pursue a career in academic pharmacy (Figure 1). One of the most interesting outcomes of the course was identified when we asked the students if they had any additional reflections on the course now that they had the benefit of additional time to reflect upon their experiences. Students cited many instances where the course helped to prepare them in the development of their research and presentations skills, as they found this to be very advantageous during APPE rotations as well as residency interviews. It was common to find students citing the advantages they felt over peers who did not take the course in these reflections as well as the benefits they found from attending the AACP Annual Meeting. Excerpts provided by the students are found in Appendix IV.

Figure 1.

The Likelihood That a Student in the Course Will Pursue a Career in Academic Pharmacy.

Students were also asked to expand upon how they felt the course has impacted their career goals. Most of the students felt they had a stronger inclination to pursue an academic position or consider an academic position than they would have if they did not have this experience. It was commonly stated that the course helped shape their decisions on which residency to pursue and their overall career goals. Excerpts provided by the students are found in Appendix IV.

DISCUSSION

Even though the dire predictions of 18.5 vacant faculty positions per pharmacy program never materialized,3 the latest data from AACP do indicate a vacancy rate of 3.9 positions per pharmacy program, attributed to a variety of factors, including budget limitations/inability to offer a competitive salary, geographic location, and a lack of qualified candidates (through both a dearth of applicants and the inability of applicants to meet the institution’s expectations).4 While the budgetary and geographic factors cannot be remedied by a didactic course, increased exposure to and preparation for career opportunities in academic pharmacy can increase student interest in pursuing this career path (Figure 1). Unlike pharmacy careers in retail or clinical settings, there are no campus-based student chapters of national pharmacy organizations whose primary purpose is to promote career opportunities within academic pharmacy and guide students towards the necessary achievements to be competitive applicants for a pharmacy faculty position; these responsibilities fall to current faculty members. Thus, this elective course is a very successful early opportunity for pharmacy students to be immersed in the life of an academic pharmacist.

Although a few other elective courses in academic pharmacy have been described, to our knowledge, the format of this course is unique within pharmacy education, as the other examples we have found lack the integrated research project and attendance at AACP, and focus more on educational theory and pedagogy without exploration of ACPE standards.26-28 We also involve the college deans, department chairs and faculty from both departments to give multiple points of view and windows into the academic pharmacy profession. The course provides a strong introduction to a potential faculty member to the teaching, scholarship and service that compose the three-legged stool of a faculty member. Major advantages of the course include inviting the appropriate dean/director/chair or faculty member of our program to lead the discussion that is relevant to their area when instructing on ACPE standards. A noteworthy example of this is when the director of admissions discusses ACPE standards for admissions. The students in the class sit through a mock admissions committee meeting and are asked to vote on students based upon the assigned metrics; this provides an opportunity for them to experience a vital part of the functioning of a pharmacy program that they would not have access to under normal circumstances. The discussion led by the department chairs focused on what they look for in potential faculty members, which gave the students insight into the criteria they should strive to meet in order to be hired as a faculty member in the future.

Another component that students found to be extremely valuable was the 45-minute teaching presentation they were required to give to the class. This is often the first presentation of that duration they have given individually, and it is commonly cited as an experience the students really feel benefits them once they complete it. The opportunity to complete a scholarly project is another major benefit to the students as this is often their first introduction to scholarly research. Students were provided a great deal of mentoring in the design and execution of their project, including working on survey design, data collection and analysis, abstract submission, poster presentations, and manuscript drafting in order to successfully complete their projects. Finally, we think and the evaluative data show that the students all derived great benefit from not only attending the AACP Annual Meeting, but also presenting at it. This is likely the most unique and rewarding aspect of the course for the students. Furthermore, the fact that all abstracts submitted have been accepted demonstrates the quality of the proposals that the students put together. Multiple participants have cited the experiences as their favorite or most valuable throughout pharmacy school and it has helped develop the credentials needed in applying for residency and faculty positions, while also allowing them to make connections beyond the faculty of our program.

The course does suffer from a significant limitation that merits mention. A vexing issue with the course design is that it is logistically limited to the spring semester (in order to incorporate AACP meeting attendance as part of the course), which means there are only a few weeks from the start of the semester until the AACP abstract submission deadline in mid-February. As such, the students must quickly become comfortable with research design and scholarly methods in order to create a research study that can be IRB approved, submitted to the target audience, and then completed in time to submit an abstract to the AACP annual meeting. Often this requires the students to complete precourse work during the fall semester when their focus is on their current course load and not on a forthcoming course.

The evaluative data, peer review of the scholarly research and student perceptions of their interest in pursuing academic pharmacy demonstrate the rigor and impact that the course had. Additionally, the course should be able to be implemented into most pharmacy programs, assuming that: there are elective course opportunities within their program; no didactic courses take place during the month of July (which would make student attendance at the AACP Annual Meeting problematic); they have the support of the program’s administration to teach a time- and resource-intensive course; and they can adequately address the financial obligations of student AACP Annual Meeting attendance, either through enrolling students with the financial wherewithal (existing capital or available financial credit) to attend the AACP Annual Meeting, or the pharmacy program has financial resources available to support (in part or in full) class attendance at the meeting. There are additional considerations that must be addressed when taking a group of students to a conference in a distant location, including travel and lodging arrangements, liability waivers, AACP membership, conference registration, and meals. However, most pharmacy programs (or their parent institution) likely have procedures in place for students attending conferences.

SUMMARY

This elective course was designed to immerse students in the life of an academic faculty member. Unique course components include attendance at the AACP Annual Meeting and the design and execution of a research project. To date, all seven research projects have produced abstracts that were accepted for presentation at the AACP Annual Meeting, allowing the students to present at the premiere national academic pharmacy conference. The course also incorporates didactic sessions focusing on teaching pedagogy, and students prepare an academic lecture on a topic of their choosing. The course involves deans, department chairs, and faculty members from both departments to give multiple points of view and windows into the academic pharmacy profession. This course is relevant to pharmacy education, as well-motivated and qualified instructors are needed to best serve the future generations of pharmacists.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank all of the faculty members at Western New England University who contributed to this course.

Appendix I. Course Outline and Assignments

Appendix II. Grading Rubric, Individual Teaching Project

Appendix III. Accepted Abstracts and Student Authors, AACP Annual Meeting 22,23

Appendix IV. Excerpts of Student Reflections on the Course

REFERENCES

- 1.Acute shortage of faculty at U.S. pharmacy schools threatens efforts to solve nation’s pharmacist shortage. July 9, 2003. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/acute-shortage-of-faculty-at-us-pharmacy-schools-threatens-efforts-to-solve-nations-pharmacist-shortage-70844342.html.

- 2.DeLuca PP. Looking ahead: the pharmaceutical science industry. Pharm Technol. 2009;33(10) http://www.pharmtech.com/looking-ahead-pharmaceutical-science-industry [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faculty shortages plague the Academy. Acad Pharm Now. 2008;1:12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Institutional research brief number 18: vacant budgeted and lost faculty positions – academic year 2014-15. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Documents/IRB%20No%2018%20-%20Faculty%20Vacancies.pdf.

- 5.Glover ML, Armayor GM. Expectations and orientation activities of first-year pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4):Article 87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter O, Nathisuwan S, Stoddard GJ, Munger MA. Faculty turnover within academic pharmacy departments. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(2):197–201. doi: 10.1177/106002800303700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor CT, Berry TM. A pharmacy faculty academy to foster professional growth and long-term retention of junior faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 32. doi: 10.5688/aj720232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fjortoft N, Mai T, Winkler SR. Use of adjunct faculty members in classroom teaching in departments of pharmacy practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(7):Article 129. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter RA. Planting faculty seed. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5):Article 94. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higby GJ, Stroud ED. American Pharmacy: A Collection of Historical Essays. Madison, WI: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy; 2005.

- 11. Svinicki M, McKeachie WJ. McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers. 14th Ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2013.

- 12.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. 2015. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf.

- 13.Ascione FJ. In pursuit of prestige: the folly of the US News and World Report survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6):Article 103. doi: 10.5688/ajpe766103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle CJ. Hiring residents as faculty members: dancing with the stars. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(8):Article 143. doi: 10.5688/ajpe768143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown D. From shortage to surplus: the hazards of uncontrolled academic growth. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article 185. doi: 10.5688/aj7410185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bongartz J, Vang C, Havrda D, Fravel M, McDanel D, Farris KB. Student pharmacist, pharmacy resident, and graduate student perceptions of social interactions with faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):Article 80. doi: 10.5688/ajpe759180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cain J, Romanelli F, Smith KM. Academic entitlement in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(10):Article 189. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7610189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poirier TI, Wilhelm M. Use of humor to enhance learning: bull’s eye or off the mark. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(2):Article 27. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. 2016-2017 Profile of Pharmacy Faculty. Alexandria VA: AACP; 2017.

- 20. Colon M. AACP research/education abstract notification [e-mail correspondence]. Received April 24, 2014.

- 21. Colon M. AACP research/education abstract notification [e-mail correspondence]. Received April 4, 2013.

- 22. Abstracts of the 115th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Grapevine, TX, Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5):Article 111.

- 23.Abstracts of the 114th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Chicago, IL. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77:Article 109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galinski CN, Horosz PJ, Spooner JJ, Kennedy DR. Comparison of introductory pharmacy practice experiences among US pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(9):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe789162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scalise AA, Lezaja GS, Nemec EC, Spooner JJ, Kennedy DR. Valued characteristics of community pharmacy residency applicants. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56(6):643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baia P, Strang A. An elective course to promote academic pharmacy as a career. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(2):Article 30. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. University of Wisconsin description of professional electives. https://pharmacy.wisc.edu/student-resources/pharmd-professional-electives-sop/

- 28.Rigelsky J. Exposing doctor of pharmacy students to an academic career through a teaching elective. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):Article 72. [Google Scholar]