ABSTRACT

Both preexisting immunity to influenza and age have been shown to be correlates of influenza vaccine responses. Frailty, an indicator of functional impairment in older adults, was also shown in one study to predict lower influenza vaccine responses among nonveterans. In the current study, we aimed to determine the associations between frailty, preexisting immunity, and immune responses to influenza vaccine among older veterans. We studied 117 subjects (age range, 62 to 95 years [median age, 81 years]), divided into three cohorts based on the Fried frailty test, i.e., nonfrail (NF) (n = 23 [median age, 68 years]), prefrail (n = 50 [median age, 80 years]), and frail (n = 44 [median age, 82 years]), during the 2010-2011 and 2011-2012 influenza seasons. Subjects received the seasonal trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, and baseline and postvaccination samples were obtained. Anti-influenza humoral immunity, as measured by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) and microneutralization assays, was measured for influenza B, A(H1N1)pdm09, and A(H3N2) viruses. Postvaccination titers were not different between frail and NF subjects overall in this older subset of veterans. However, preexisting HI titers were strongly correlated with postvaccination titers among all functional status groups. When microneutralization titers were compared, the association between preexisting immunity and vaccine responses varied by frailty status, with the strongest correlation being observed for the NF group. In conclusion, preexisting immunity rather than frailty appeared to predict postvaccination titers in this older veteran cohort.

KEYWORDS: Frailty, influenza vaccines

INTRODUCTION

Seasonal influenza has disproportionately greater adverse effects on older adults. While persons over the age of 65 years represent roughly 13% of the U.S. population, the overwhelming majority of influenza-related deaths and most hospitalizations occur in this population (1–4). This pattern is even more pronounced among persons at the older extreme of this group (2). Age-associated impairment of cell-mediated immunity renders older adults increasingly susceptible to infections and also results in reduced immune responses to vaccinations, the very strategy used to prevent infections (5–7). Influenza has served as a prime example of this paradigm (8). While influenza vaccines can reduce complications such as pneumonia and hospitalizations among older adults (9, 10), the magnitude of mortality and morbidity benefits among older versus younger adults has been a source of debate (11, 12).

This discrepancy in evidence highlights the heterogeneous nature of this population. One source of variability is preexisting immunity to influenza. In fact, preexisting immunity to influenza has been proposed as a greater correlate of immunity to influenza than age among elderly persons (13). Another potential source of variable responses to influenza vaccines is functional decline or frailty. Frailty syndrome, which is an indicator of functional impairment in older adults, is a strong marker of increased risk for poor health outcomes, including falls, disability, and death (14). There is increasing evidence to suggest that frailty also negatively affects the immune system, more than would be expected as a result of aging. The existence of a dysregulated immune system, marked by a heightened inflammatory state and increases in levels of immunological markers of T cell senescence, has been identified in frail older adults (15). B lymphocyte diversity has been shown to decline in frail individuals, making them more susceptible to novel antigens via natural infection or immunization (16). Frailty has also been shown to have an impact on the innate immune system. Decreased production of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligand-induced interleukin 12p70 (IL-12p70) and IL-23, cytokines that play important roles in protection against pathogens, has been associated with frailty rather than age (17). There are some data to suggest that frailty may adversely affect responses to influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations (18–20). Further studies are needed to better understand the immune responses to influenza and vaccination, particularly among frail elderly persons.

In the present study, we sought to determine the relationships between frailty and strain-specific influenza hemagglutination inhibition (HI) and microneutralization assay results among older veterans. These results may help identify those older adults who are most likely to have decreased responses to influenza vaccination and, as a result, persisting risk for morbidity and death from influenza despite vaccination.

RESULTS

We classified 117 subjects according to the three Fried frailty phenotype categories, i.e., nonfrail (NF) (n = 23), prefrail (PF) (n = 50), and frail (F) (n = 44). The prevalence of frailty in this cohort was 43%, while prefrailty was identified for 38% of the subjects. The median age for the NF group (68 years [range, 62 to 90 years]) was significantly lower than that for the PF group (80 years [range, 62 to 92 years]) and that for the frail group (82 years [range, 62 to 92 years]). As expected for an older veteran population, the subjects were primarily male (96%). African Americans accounted for over one-half (54%) of the study subjects. Prevaccination seroprotection rates were similar for all viruses (B, 27%; H1N1, 24%; H3N2, 28%). After vaccination, seroprotection rates were significantly higher for A(H3N2) (64%) than for A(H1N1)pdm09 (50%) and B (47%) viruses (P = 0.02). These rates did not vary based on frailty status (data not shown), and 87% of subjects had received the seasonal influenza vaccine in the preceding year.

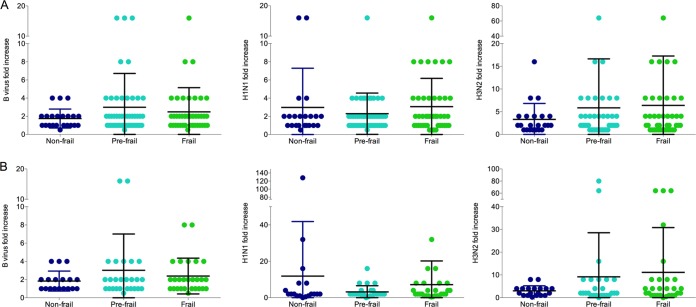

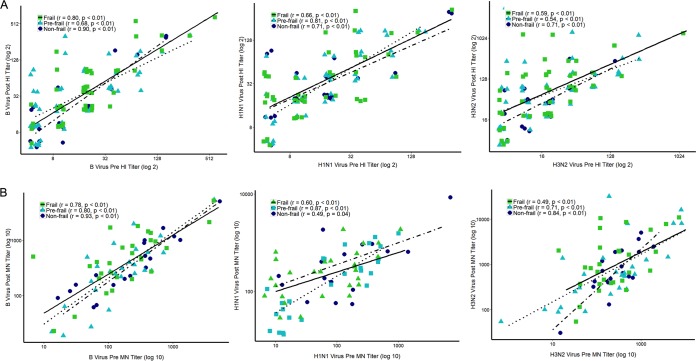

We compared immune responses to influenza vaccination, as measured by geometric mean titer (GMT) ratios (from HI and microneutralization assays), across frailty groups. Mean HI fold increases in response to B (NF, 3.0-fold; PF, 2.3-fold; F, 3.1-fold), A(H1N1)pdm09 (NF, 2.9-fold; PF, 2.3-fold; F, 3.1-fold), and A(H3N2) (NF, 3.3-fold; PF, 5.9-fold; F, 6.4-fold) viruses were similar among the three groups (Fig. 1A). Microneutralization fold increases after vaccination were also similar between frailty groups (Fig. 1B). Additionally, while aging was generally associated with lower levels of immunity to influenza, the correlations were not statistically significant when evaluated separately within frailty groups (data not shown). In contrast, preexisting immunity to influenza was found to be strongly correlated with postvaccination titers (Fig. 2). HI prevaccination titers were strongly correlated with postvaccination titers among all functional status groups (B virus: F, r = 0.72 [P < 0.0001]; PF, r = 0.69 [P < 0.0001]; NF, r = 0.80 [P < 0.000]; H1N1 virus: F, r = 0.60 [P < 0.001]; PF, r = 0.82 [P < 0.0001]; NF, r = 0.53 [P = 0.01]; H3N2 virus: F, r = 0.57 [P < 0.001]; PF, r = 0.60 [P < 0.001]; NF, r = 0.58 [P = 0.004]) (Fig. 2A). When microneutralization titers were compared, the association between preexisting immunity and postvaccination titers varied by frailty status, with the strongest correlations being observed among the NF subjects for B virus and H3N2 virus (B virus: F, r = 0.76 [P < 0.0001]; PF, r = 0.72 [P < 0.0001]; NF, r = 0.94 [P < 0.0001]; H1N1 virus: F, r = 0.58 [P = 0.001]; PF, r = 0.84 [P < 0.005]; NF, r = 0.47 [P = 0.04]; H3N2 virus: F, r = 0.41 [P = 0.02]; PF, r = 0.72 [P < 0.005]; NF, r = 0.75 [P < 0.001]) (Fig. 2B).

FIG 1.

Comparison of hemagglutination inhibition (HI) (A) and microneutralization (MN) (B) postvaccination/prevaccination geometric mean titer (GMT) ratios within frailty groups. No statistically significant differences, as measured by one-way ANOVA, were found between frailty groups. Horizontal black lines represent the mean, and the vertical lines represent 1 standard deviation (SD).

FIG 2.

Correlation of preexisting immunity with postvaccination responses, as measured by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) (A) and microneutralization (MN) (B) assays. Antibody levels were plotted within frailty groups, and correlations were calculated to determine the effect of preexisting immunity on postvaccination antibody titers. The Spearman correlation coefficient and P value are presented for each frailty group.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated relationships between frailty status and influenza vaccine responses among older veterans, with a secondary aim of examining the role of preexisting immunity in older adults. Seroprotection rates were higher for A(H3N2) than A(H1N1)pdm09 or B viruses. In our cohort, HI or microneutralization fold increases did not differ by frailty status. When assessed within frailty groups, increased age was not significantly associated with lower influenza vaccine responses. Prevaccination strain-specific immunity was found to be strongly associated with postvaccination responses in all frailty groups, with the greatest correlations in microneutralization titers being observed for the nonfrail group.

Overall seroprotection rates were lower for A(H1N1)pdm09 and B viruses than for A(H3N2) virus. These rates did not differ by frailty status. Our observed rates of seroprotection were similar to findings reported for older adults, including greater immune protection against A(H3N2) (13). Incidentally, among older adults, A(H3N2) virus has been found to be associated with more severe morbidity and increased mortality rates, compared with A(H1N1)pdm09 (2, 3). Notably, there were similar levels of prevaccination seroprotection for all three viruses. The 2010-2011 influenza season was preceded by the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic, which occurred from April 2009 through June 2010 (21). The circulating virus during that period was predominantly A(H1N1)pdm09, with less than 1% of cases representing A(H3N2) or B viruses. This prompted a change in the 2010-2011 trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) components, with replacement of the A(H1N1) strain by the pandemic A(H1N1)pdm09 strain. The A(H3N2) strain was also changed from A/Brisbane/10/2007 to A/Perth/16/2009. The B strain was the only component preserved during that year. Changes in vaccine strains offer an opportunity for greater GMT fold changes, due to the presence of a new antigen. This effect may be blunted in older adults because of reduced immunity to novel antigens.

While immunosenescence is thought to contribute to decreased effectiveness of immunizations among older adults, age alone is likely not the entire explanation for this phenomenon. There is evidence to suggest that a number of factors, such as functional status and preexisting immunity, also play a role (22). While there is growing literature on the association between functional decline and immunosenescence, there are limited data on influenza-specific responses among frail elderly persons. Data from an observational study demonstrated potentially lower clinical efficacy of influenza vaccination among vaccinated frail, compared with nonfrail, nursing home residents, as demonstrated by increasing all-cause mortality rates with increasingly impaired functional status (18). To the best of our knowledge, there is only one other published report specifically comparing strain-specific immunity to influenza among frailty groups (19). Our results differ from those of Yao and colleagues (19), who found frailty to be associated with impairment in TIV-induced strain-specific immunity to influenza, as measured by HI titers. Incidentally, they also demonstrated increased rates of influenza-like illness and laboratory-confirmed influenza infections. Apart from differences in veteran versus nonveteran populations, an important difference between our studies is the influenza seasons studied. Not only was the 2007-2008 influenza season documented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as moderate in severity, but also the TIV A(H3N2) and B viruses were poorly matched to the circulating strains (21, 23). There is evidence that influenza vaccination is less effective during seasons with antigenic mismatch between the vaccine and circulating strains. In a study of adults older than 65 years of age in a season with antigenic mismatch, significantly higher HI titers were required to achieve the same level of protection as a well-matched vaccine; at low titers, however, some measure of protection was seen against matched virus (24). Additionally, vaccine effectiveness may be related to the risk of developing influenza, with the lowest levels of protection being evident among persons at highest risk during seasons with poor matches (25, 26). In contrast, the 2011-2012 influenza season set a record for the lowest and shortest peak of influenza-like illness (27). Similarly, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the 2010-2011 influenza season was less severe than both the 2009-2010 pandemic year and the 2007-2008 season (27). As noted previously, the vaccine components were unchanged during those 2 years. In fact, estimates of the 2011-2012 TIV effectiveness demonstrated that, with unchanged vaccine components, protection may have extended beyond a single season (28). All of these factors may have contributed to a lack of demonstrable differences among the frailty groups in the present study. The overwhelming majority of our subjects had received influenza vaccinations in previous years, which may have resulted in similar immune responses regardless of functional status.

Preexisting immunity was a strong correlate of postvaccination immunity in our cohort. This is consistent with a previously published report by Reber and colleagues, in which prevaccination titers were the best predictor of postvaccination immunity to influenza among adults older than 50 years of age (13). In fact, those authors found age to be only modestly associated with lower vaccine responses. We also did not find age to be a significant negative factor when it was evaluated within the frailty groups. Although A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) strains were replaced in the 2010-2011 vaccine, they were replaced by previously circulating strains. The overwhelming majority of subjects in our study had been vaccinated the previous year. The strains were entirely preserved for the 2011-2012 season. Therefore, through either immunization or natural infection, subjects were likely to have had more cross-protective immunity to influenza A. The importance of preexisting immunity was underscored during the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic, when older adults were less severely affected than younger individuals (29, 30). Young adults had little evidence of cross-reactive antibodies to the pandemic virus, while a large proportion of older adults had preexisting cross-reactive immunity to the A(H1N1)pdm09 strain.

Our study had several limitations. The study involved a small sample at a single institution, and the results may not be generalizable. Due to the small sample size, we are unable to make any clinical inferences. While prevaccination titers were correlated with postvaccination titers, they do not inform us regarding vaccine effects.

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of preexisting immunity against influenza to mitigate the ill effects of immunosenescence associated with functional decline. The data underscore the range of factors that can alter postvaccination titers to influenza vaccines among older adults, and they highlight prevaccination titers, which are likely influenced by prior vaccination and antigen exposure history, as important determinants of seroprotection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting, sample, and study design.

This was an observational study in which veterans 60 years of age or older, receiving care at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center (LSCVAMC) outpatient geriatrics and internal medicine clinics, were enrolled over two influenza seasons. Persons who were receiving immunosuppressive medications or had immunosuppressive conditions, such as HIV, chemotherapy for cancer treatment, or severe anemia, were excluded from the study. Subjects for whom influenza vaccination was contraindicated due to allergy to any component of the vaccine were also excluded. Subjects were recruited during the 2010-2011 and 2011-2012 influenza seasons. Subjects could participate for only one season. Serum samples were obtained at the time of administration of the seasonal TIV and 2 to 4 months postvaccination. The 2010-2011 TIV contained A/California/7/09-like virus (the 2009 pandemic H1N1 strain), A/Perth/16/2009-like virus (H3N2), and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus strains. The 2011-2012 TIV contained the same strains and represented no change from the previous season. All subjects completed frailty testing at the time of admission to the study. We analyzed data for 117 subjects (age range, 62 to 95 years [median age, 81 years]). Human experimentation guidelines of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services were followed in the conduct of this study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the LSCVAMC, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Frailty assessment.

The Fried frailty phenotype assessment, a widely accepted and validated instrument for frailty measurement among older adults, was utilized for functional assessments (14). Study staff members evaluated the five components of the Fried frailty assessment tool, i.e., weakness, assessed by grip strength (an average of 3 trials with the dominant hand, measured with a Jamar dynamometer), walking speed (one way for 15 feet in a straight line), unintended weight loss of ≥10 pounds in the past year, self-reported exhaustion (two Likert-type questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression [CES-D] scale [32]), and physical activity, based on the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity (LTA) questionnaire (33). Grip strength was stratified by sex and body mass index, walking speed was stratified by sex and height, and physical activity scores were stratified by sex, as suggested by Fried and colleagues (31). Subjects were assigned to the nonfrail (NF) category for 0 criteria met on the Fried frailty instrument, prefrail (PF) for 1 or 2 criteria met, and frail (F) for 3 or more criteria met.

Laboratory measurements.

Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) and microneutralization assays for influenza B, A(H1N1)pdm09, and A(H3N2) viruses were used. HI and microneutralization titers were determined using routine methods, as described previously (34–37). The microneutralization assay has been shown to have better sensitivity in detecting serum antibodies than HI assays, and findings correlate with protection against seasonal influenza (38–40). However, HI assays offer several advantages, i.e., they are relatively simple and inexpensive to perform and are widely used around the world, allowing easier comparisons and perhaps standardization (41). Results of the assays are expressed as GMT. Seroconversion was defined as a ≥4-fold increase in HI GMT from baseline. Seroprotection was defined as a postvaccination HI titer of ≥1:40.

Statistical analysis.

Analyses were performed with SPSS, GraphPad Prism 6.0, and R 3.2.2, using the ggplot2 package to graphically represent the data. Differences in GMT ratios (prevaccination/postvaccination HI or microneutralization titers) among frailty groups were calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA). For prevaccination-postvaccination titer comparisons, log2-transformed HI or microneutralization prevaccination and postvaccination titers were used as independent and dependent variables, respectively. Associations between age and fold increases in titers, both overall and within frailty groups, were examined using Spearman rank correlations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the U.S. veterans who participated in this study.

The work was supported by VA Merit Review funds and NIH grant AI108972.

The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza: United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59:1057–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. 2003. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. 2004. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 292:1333–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullooly JP, Bridges CB, Thompson WW, Chen J, Weintraub E, Jackson LA, Black S, Shay DK. 2007. Influenza- and RSV-associated hospitalizations among adults. Vaccine 25:846–855. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sambhara S, McElhaney JE. 2009. Immunosenescence and influenza vaccine efficacy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 333:413–429. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang PO, Govind S, Bokum AT, Kenny N, Matas E, Pitts D, Aspinall R. 2013. Immune senescence and vaccination in the elderly. Curr Top Med Chem 13:2541–2550. doi: 10.2174/15680266113136660181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Della Bella S, Iorio AM, Michel JP, Pawelec G, Solana R. 2009. Immunosenescence and vaccine failure in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res 21:201–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03324904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu WM, van der Zeijst BA, Boog CJ, Soethout EC. 2011. Aging and impaired immunity to influenza viruses: implications for vaccine development. Hum Vaccin 7(Suppl):94–98. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.0.14568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichol KL, Nordin J, Mullooly J, Lask R, Fillbrandt K, Iwane M. 2003. Influenza vaccination and reduction in hospitalizations for cardiac disease and stroke among the elderly. N Engl J Med 348:1322–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J, Von Sternberg T. 1994. The efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination against influenza among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 331:778–784. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409223311206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, Blackwelder WC, Taylor RJ, Miller MA. 2005. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med 165:265–272. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, Neuzil KM, Barlow W, Jackson LA. 2008. Influenza vaccination and risk of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent elderly people: a population-based, nested case-control study. Lancet 372:398–405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reber AJ, Kim JH, Biber R, Talbot HK, Coleman LA, Chirkova T, Gross FL, Steward-Clark E, Cao W, Jefferson S, Veguilla V, Gillis E, Meece J, Bai Y, Tatum H, Hancock K, Stevens J, Spencer S, Chen J, Gargiullo P, Braun E, Griffin MR, Sundaram M, Belongia EA, Shay DK, Katz JM, Sambhara S. 2015. Preexisting immunity, more than aging, influences influenza vaccine responses. Open Forum Infect Dis 2:ofv052. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. 2001. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang GC, Casolaro V. 2014. Immunologic changes in frail older adults. Transl Med UniSa 9:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson KL, Wu YC, Barnett Y, Duggan O, Vaughan R, Kondeatis E, Nilsson BO, Wikby A, Kipling D, Dunn-Walters DK. 2009. B-cell diversity decreases in old age and is correlated with poor health status. Aging Cell 8:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compte N, Zouaoui Boudjeltia K, Vanhaeverbeek M, De Breucker S, Tassignon J, Trelcat A, Pepersack T, Goriely S. 2013. Frailty in old age is associated with decreased interleukin-12/23 production in response to Toll-like receptor ligation. PLoS One 8:e65325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan TC, Hung IF, Luk JK, Shea YF, Chan FH, Woo PC, Chu LW. 2013. Functional status of older nursing home residents can affect the efficacy of influenza vaccination. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68:324–330. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao X, Hamilton RG, Weng NP, Xue QL, Bream JH, Li H, Tian J, Yeh SH, Resnick B, Xu X, Walston J, Fried LP, Leng SX. 2011. Frailty is associated with impairment of vaccine-induced antibody response and increase in post-vaccination influenza infection in community-dwelling older adults. Vaccine 29:5015–5021. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridda I, Macintyre CR, Lindley R, Gao Z, Sullivan JS, Yuan FF, McIntyre PB. 2009. Immunological responses to pneumococcal vaccine in frail older people. Vaccine 27:1628–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010. Update: influenza activity: United States, 2009–10 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59:901–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson MG, Naleway A, Fry AM, Ball S, Spencer SM, Reynolds S, Bozeman S, Levine M, Katz JM, Gaglani M. 2016. Effects of repeated annual inactivated influenza vaccination among healthcare personnel on serum hemagglutinin inhibition antibody response to A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2)-like virus during 2010–11. Vaccine 34:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belongia EA, Irving SA, Waring SC, Coleman LA, Meece JK, Vandermause M, Lindstrom S, Kempf D, Shay DK. 2010. Clinical characteristics and 30-day outcomes for influenza A 2009 (H1N1), 2008–2009 (H1N1), and 2007–2008 (H3N2) infections. JAMA 304:1091–1098. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunning AJ, DiazGranados CA, Voloshen T, Hu B, Landolfi VA, Talbot HK. 2016. Correlates of protection against influenza in the elderly: results from an influenza vaccine efficacy trial. Clin Vaccine Immunol 23:228–235. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00604-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrera GA, Iwane MK, Cortese M, Brown C, Gershman K, Shupe A, Averhoff F, Chaves SS, Gargiullo P, Bridges CB. 2007. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among 50–64-year-old persons during a season of poor antigenic match between vaccine and circulating influenza virus strains: Colorado, United States, 2003–2004. Vaccine 25:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosterin Hopping A, McElhaney J, Fonville JM, Powers DC, Beyer WE, Smith DJ. 2016. The confounded effects of age and exposure history in response to influenza vaccination. Vaccine 34:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Update: influenza activity: United States, 2010–11 season, and composition of the 2011–12 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60:705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, Sabaiduc S, De Serres G, Winter AL, Gubbay JB, Dickinson JA, Fonseca K, Charest H, Bastien N, Li Y, Kwindt TL, Mahmud SM, Van Caeseele P, Krajden M, Petric M. 2014. Influenza A/subtype and B/lineage effectiveness estimates for the 2011–2012 trivalent vaccine: cross-season and cross-lineage protection with unchanged vaccine. J Infect Dis 210:126–137. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, Zhong W, Butler EN, Sun H, Liu F, Dong L, DeVos JR, Gargiullo PM, Brammer TL, Cox NJ, Tumpey TM, Katz JM. 2009. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N Engl J Med 361:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaglani M, Spencer S, Ball S, Song J, Naleway A, Henkle E, Bozeman S, Reynolds S, Sessions W, Hancock K, Thompson M. 2014. Antibody response to influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 among healthcare personnel receiving trivalent inactivated vaccine: effect of prior monovalent inactivated vaccine. J Infect Dis 209:1705–1714. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K, Chaves PH, Johnson BA. 2000. Preclinical mobility disability predicts incident mobility disability in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55:M43–M52. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.M43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. 1986. Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol 42:28–33. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. 1978. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 31:741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potter CW, Oxford JS. 1979. Determinants of immunity to influenza infection in man. Br Med Bull 35:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobson D, Curry RL, Beare AS, Ward-Gardner A. 1972. The role of serum haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody in protection against challenge infection with influenza A2 and B viruses. J Hyg (Lond) 70:767–777. doi: 10.1017/S0022172400022610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clements ML, Betts RF, Tierney EL, Murphy BR. 1986. Serum and nasal wash antibodies associated with resistance to experimental challenge with influenza A wild-type virus. J Clin Microbiol 24:157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faix DJ, Hawksworth AW, Myers CA, Hansen CJ, Ortiguerra RG, Halpin R, Wentworth D, Pacha LA, Schwartz EG, Garcia SM, Eick-Cost AA, Clagett CD, Khurana S, Golding H, Blair PJ. 2012. Decreased serologic response in vaccinated military recruits during 2011 correspond to genetic drift in concurrent circulating pandemic A/H1N1 viruses. PLoS One 7:e34581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu JP, Zhao X, Chen MI, Cook AR, Lee V, Lim WY, Tan L, Barr IG, Jiang L, Tan CL, Phoon MC, Cui L, Lin R, Leo YS, Chow VT. 2014. Rate of decline of antibody titers to pandemic influenza A (H1N1-2009) by hemagglutination inhibition and virus microneutralization assays in a cohort of seroconverting adults in Singapore. BMC Infect Dis 14:414. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grund S, Adams O, Wahlisch S, Schweiger B. 2011. Comparison of hemagglutination inhibition assay, an ELISA-based micro-neutralization assay and colorimetric microneutralization assay to detect antibody responses to vaccination against influenza A H1N1 2009 virus. J Virol Methods 171:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verschoor CP, Singh P, Russell ML, Bowdish DM, Brewer A, Cyr L, Ward BJ, Loeb M. 2015. Microneutralization assay titres correlate with protection against seasonal influenza H1N1 and H3N2 in children. PLoS One 10:e0131531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noah DL, Hill H, Hines D, White EL, Wolff MC. 2009. Qualification of the hemagglutination inhibition assay in support of pandemic influenza vaccine licensure. Clin Vaccine Immunol 16:558–566. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00368-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]