Guitart et al. performed an in vivo genetic dissection of the Krebs cycle enzyme fumarate hydratase (Fh1) in the hematopoietic system. Their investigations revealed multifaceted functions of Fh1 in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell biology and leukemic transformation.

Abstract

Strict regulation of stem cell metabolism is essential for tissue functions and tumor suppression. In this study, we investigated the role of fumarate hydratase (Fh1), a key component of the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and cytosolic fumarate metabolism, in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. Hematopoiesis-specific Fh1 deletion (resulting in endogenous fumarate accumulation and a genetic TCA cycle block reflected by decreased maximal mitochondrial respiration) caused lethal fetal liver hematopoietic defects and hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) failure. Reexpression of extramitochondrial Fh1 (which normalized fumarate levels but not maximal mitochondrial respiration) rescued these phenotypes, indicating the causal role of cellular fumarate accumulation. However, HSCs lacking mitochondrial Fh1 (which had normal fumarate levels but defective maximal mitochondrial respiration) failed to self-renew and displayed lymphoid differentiation defects. In contrast, leukemia-initiating cells lacking mitochondrial Fh1 efficiently propagated Meis1/Hoxa9-driven leukemia. Thus, we identify novel roles for fumarate metabolism in HSC maintenance and hematopoietic differentiation and reveal a differential requirement for mitochondrial Fh1 in normal hematopoiesis and leukemia propagation.

Introduction

Successful clinical application of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is critically dependent on their ability to give long-term multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution (Weissman and Shizuru, 2008). Multiple studies have revealed the paradigmatic transcription factors driving HSC self-renewal and differentiation to sustain multilineage hematopoiesis (Göttgens, 2015). Emerging evidence indicates that strict control of HSC metabolism is also essential for their life-long functions (Suda et al., 2011; Manesia et al., 2015), but the key metabolic regulators that ensure stem cell integrity remain elusive. Although highly proliferative fetal liver (FL) HSCs use oxygen-dependent pathways for energy generation (Suda et al., 2011; Manesia et al., 2015), adult HSCs are known to suppress the flux of glycolytic metabolites into the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and heavily rely on glycolysis to maintain their quiescent state (Simsek et al., 2010; Takubo et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). Whereas pharmacological inhibition of glycolytic flux into the TCA cycle enhances HSC activity upon transplantation (Takubo et al., 2013), severe block of glycolysis (i.e., Ldha deletion) and a consequent elevated mitochondrial respiration abolishes HSC maintenance (Wang et al., 2014). The switch from glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is essential for adult HSC differentiation rather than maintenance of their self-renewing pool (Yu et al., 2013). Leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) are even more dependent on glycolysis than normal HSCs (Wang et al., 2014). Partial or severe block in glycolysis (elicited by deletion of Pkm2 or Ldha, respectively) and a metabolic shift to mitochondrial respiration efficiently suppress the development and maintenance of LICs (Lagadinou et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). Thus, the maintenance of adult self-renewing HSCs and LICs appears to depend critically on glycolysis rather than the mitochondrial TCA, which is thought to be less important for this process. However, thus far, the requirement for any of the TCA enzymes in FL and adult HSC and LIC maintenance has not been investigated.

Genetic evidence in humans indicates that rare recessive mutations in the FH gene encoding a TCA enzyme fumarate hydratase (Fh1) result in severe developmental abnormalities, including hematopoietic defects (Bourgeron et al., 1994). Consistent with this, we also found that monozygous twins with recessive FH mutations (Tregoning et al., 2013) display leukopenia and neutropenia (Table S1), thus suggesting a role for FH in the regulation of hematopoiesis. Mitochondrial and cytosolic fumarate hydratase enzyme isoforms, both encoded by the same gene (called FH in humans and Fh1 in mice; Stein et al., 1994; Sass et al., 2001), catalyze hydration of fumarate to malate. Whereas mitochondrial Fh1 is an integral part of the TCA cycle, cytosolic Fh1 metabolizes fumarate generated during arginine synthesis, the urea cycle, and the purine nucleotide cycle in the cytoplasm (Yang et al., 2013). Autosomal dominant mutations in FH are associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer, indicating that FH functions as a tumor suppressor (Launonen et al., 2001; Tomlinson et al., 2002). Given that FH mutations have been associated with hematopoietic abnormalities and tumor formation, here, we investigated the role of Fh1 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis.

Results

Fh1 is required for FL hematopoiesis

Fh1 is uniformly expressed in mouse Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) CD48−CD150+ HSCs, LSKCD48−CD150− multipotent progenitors, primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs; i.e., LSKCD48+CD150− HPC-1 and LSKCD48+CD150+ HPC-2 populations), and Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+ (LK) myeloid progenitors sorted both from the FL (the major site of definitive hematopoiesis during development) of 14.5–days postcoitum (dpc) embryos and adult BM (Fig. 1 A). To determine the requirement for Fh1 in HSC maintenance and multilineage hematopoiesis, we conditionally deleted Fh1 specifically within the hematopoietic system shortly after the emergence of definitive HSCs using the Vav-iCre deleter strain (de Boer et al., 2003). We bred Fh1fl/fl mice (Pollard et al., 2007) with Vav-iCre mice and found no viable Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre offspring (Table S2). Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre embryos were recovered at 14.5 dpc at normal Mendelian ratios, suggesting fetal or perinatal lethality. FLs isolated from Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre embryos appeared abnormally small and pale indicating severe impairment in FL hematopoiesis (Fig. 1 B). Fh1 loss from the hematopoietic system was confirmed by the absence of Fh1 transcripts (Fig. 1 C) in CD45+ and c-Kit+ hematopoietic cells from Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs and absence of Fh1 protein in FL c-Kit+ cells from Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre embryos (Fig. 1 D). Whereas Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs had decreased numbers of hematopoietic cells because of reduced numbers of differentiated lineage+ (Lin+) cells, the numbers of primitive FL Lin− cells remained unchanged (Fig. 1 E). Colony-forming cell (CFC) assays indicated the failure of Fh1-deficient FL cells to differentiate (Fig. 1 F). Analyses of erythroid differentiation revealed a block of erythropoiesis resulting in severe anemia (Fig. 1 G). Fh1 is therefore essential for multilineage differentiation of FL stem and/or progenitor cells.

Figure 1.

Hematopoiesis-specific Fh1 deletion results in severe hematopoietic defects and loss of HSC activity. (A) Relative levels of Fh1 mRNA (normalized to Actb) in HSCs, multipotent progenitors (MPP), HPC-1 and HPC-2 populations, and LSK and LK cells sorted from 14.5-dpc FLs and BM of C57BL/6 adult (8–10 wk old) mice. n = 3. (B) FLs from 14.5-dpc Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre embryos are smaller and paler compared with Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre and control embryos. (C) The absence of Fh1 transcripts in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FL CD45+ and c-Kit+ cells. Control, n = 3; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 6. (D) Western blots for Fh1 and β-actin in FL c-Kit+ cells. (E) Total cellularity (the sum of Lin+ and Lin− cell numbers) in 14.5-dpc FLs of the indicated genotypes. Control, n = 17; Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 11; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 9. (F) CFC assay with FL cells. Control, n = 11; Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 8; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 4. (G) Erythropoiesis in 14.5-dpc FLs. Data are arranged from least to most differentiated: Ter119−CD71−, Ter119–CD71+, Ter119+CD71+, and Ter119+CD71–. Control, n = 11; Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 8; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 4. (H–J) Total number of LK cells (H), LSK cells (I), and HSCs (J) in 14.5-dpc FLs. Control, n = 17; Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 11; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 9. (K and L) Percentage of donor-derived CD45.2+ cells in PB (K) and total BM and the BM LSK cell compartment (L) of the recipient mice transplanted with 100 FL HSCs. n = 5–8 recipients per genotype. At least three donors were used per genotype. (M) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in PB after transplantation of 200,000 total FL cells. n = 3–4 recipients per genotype. At least three donors were used per genotype. (N and O) Acute deletion of Fh1 from the adult hematopoietic system. 5 × 105 unfractionated CD45.2+ BM cells from untreated Fh1fl/fl (control), Fh1+/fl;Mx1-Cre, and Fh1fl/fl;Mx1-Cre C57BL/6 (8–10 wk old) mice were mixed with 5 × 105 CD45.1+ WT BM cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipients. 8 wk after transplantation, the recipients received six doses of pIpC. (N) Percentage of donor-derived CD45.2+ cells in PB. n = 5–10 recipients per genotype. n = 2 donors per genotype. (O) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the Lin+, Lin−, LK, and LSK cell compartments of the recipient mice 11 wk after pIpC treatment. n = 7–8 recipients per genotype. Data are mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Fh1 is essential for HSC maintenance

Next, we asked whether Fh1 is required for the maintenance of the stem and progenitor cell compartments in FLs. FLs from Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre embryos had normal absolute numbers of LK myeloid progenitors (Fig. 1 H) and LSK stem and primitive progenitor cells (Fig. 1 I) but displayed an increase in total numbers of HSCs compared with control FLs (Fig. 1 J). To test the repopulation capacity of Fh1-deficient HSCs, we transplanted 100 CD45.2+ HSCs sorted from 14.5-dpc FLs into lethally irradiated syngeneic CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipients and found that Fh1-deficient HSCs failed to reconstitute short-term and long-term hematopoiesis (Fig. 1, K and L). To test the possibility that Fh1-deficient FLs contain stem cell activity outside the immunophenotypically defined LSKCD48−CD150+ HSC compartment, we transplanted unfractionated FL cells from Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and control embryos into lethally irradiated recipient mice (together with support BM cells) and found that Fh1-deficient FL cells failed to repopulate the recipients (Fig. 1 M). Thus, Fh1 is dispensable for HSC survival and expansion in the FL but is critically required for HSC maintenance upon transplantation.

To establish the requirement for Fh1 in adult HSC maintenance, we generated Fh1fl/fl;Mx1-Cre mice in which efficient recombination is induced by treatment with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pIpC; Kühn et al., 1995). We mixed CD45.2+ BM cells from untreated Fh1fl/fl;Mx1-Cre, Fh1+/fl;Mx1-Cre, or control mice with CD45.1+ BM cells, transplanted them into recipient mice, and allowed for efficient reconstitution (Fig. 1 N). pIpC administration to the recipients of Fh1fl/fl;Mx1-Cre BM cells resulted in a progressive decline of donor-derived CD45.2+ cell chimerism in PB (Fig. 1 N) and a complete failure of Fh1-deficient cells to contribute to primitive and mature hematopoietic compartments of the recipients (Fig. 1 O). Therefore, Fh1 is critical for the maintenance of both FL and adult HSCs.

Fh1 deficiency results in cellular fumarate accumulation and decreased maximal mitochondrial respiration

We next investigated the biochemical consequences of Fh1 deletion in primitive hematopoietic cells. To investigate how Fh1 loss affects the oxidative phosphorylation capacity of primitive FL c-Kit+ hematopoietic cells, we measured oxygen consumption rate (OCR) under basal conditions and in response to sequential treatment with oligomycin (ATPase inhibitor), carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP; mitochondrial uncoupler), and a concomitant treatment with rotenone and antimycin A (complex I and III inhibitors, respectively). The basal OCR was not affected in Fh1-deficient FL c-Kit+ cells, suggesting that the majority of mitochondrial NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced) required for oxygen consumption in these cells originates from TCA-independent sources. However, the maximal OCR (after treatment with FCCP), which reflects maximal mitochondrial respiration, was profoundly decreased in Fh1-deficient cells (Fig. 2 A; but not in Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre cells; not depicted), indicating that Fh1 deficiency may result in a compromised capacity to meet increased energy demands associated with metabolic stress or long-term survival (Yadava and Nicholls, 2007; Ferrick et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2009; van der Windt et al., 2012; Keuper et al., 2014). We also found that primitive Fh1-deficient FL hematopoietic cells failed to maintain ATP synthesis upon galactose-mediated inhibition of glycolysis (Fig. 2 B, left), consistent with an increased reliance on glycolysis for ATP production. Furthermore, Fh1-deficient c-Kit+ cells had increased expression of glucose transporters (Glut1 and Glut3) and key glycolytic enzymes Hk2 and Pfkp and displayed increased extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), indicative of enhanced glycolysis (Fig. 2, C–D). Thus, Fh1 deficiency results in an increase in glycolytic flux and impaired maximal mitochondrial respiration.

Figure 2.

Cytosolic isoform of Fh1 restores normal steady-state hematopoiesis in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre mice. (A) OCR in FL c-Kit+ cells under basal conditions and after the sequential addition of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone and antimycin A. Control, n = 5; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 3; control;FHCyt, n = 10; Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 5. (B) Oxidative phosphorylation–dependent ATP production in galactose (Gal)-treated FL c-Kit+ Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre cells. FL c-Kit+ cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with either 25 mM glucose (Glu) or 25 mM Gal. The graph shows the ratio of ATP produced in the presence of Gal (permissive for oxidative phosphorylation only) to ATP generated in the presence of Glu (permissive for both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis). Control, n = 9; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 9; control;FHCyt, n = 6; Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 10. (C) Relative expression (normalized to Actb) of genes involved in glycolysis in FL c-Kit+ cells. n = 4–5 per genotype. (D) ECAR under basal conditions in 14.5-dpc FL c-Kit+ cells. Control, n = 6; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 5; control;FHCyt, n = 10; Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 4. (E and F) Fumarate (E) and argininosuccinate (F) levels in FL c-Kit+ cells measured using LC-MS. Control, n = 6; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 4; control;FHCyt, n = 6; Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 13. (G) 14.5-dpc FL cell extracts were immunoblotted with a polyclonal anti-2SC antibody. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (H) CFU assays performed with BM cells from 8–10-wk-old mice of the indicated genotypes. CFU-red, CFU-erythroid and/or megakaryocyte; CFU-G, CFU-granulocyte; CFU-M, CFU-monocyte/macrophage; CFU-GM, CFU–granulocyte and monocyte/macrophage; CFU-Mix, at least three of the following: granulocyte, erythroid, monocyte/macrophage, and megakaryocyte. n = 3–5 per genotype and are representative of three independent experiments. (I) Total number of BM nucleated cells obtained from two tibias and two femurs of 8–10-wk-old mice. n = 3–4 per genotype. (J–N) Total numbers of CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells (J), CD19+B220+ B cells (K), LK cells (L), LSK cells (M), and HSCs (N) in two tibias and two femurs. n = 3–4 per genotype. Data are mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 (Mann-Whitney U test).

To determine the impact of Fh1 deletion on fumarate levels, we performed mass spectrometry analyses. Fh1-deficient FL c-Kit+ cells accumulated high levels of endogenous cellular fumarate (Fig. 2 E), consistent with previous observations in nonhematopoietic tissues harboring Fh1 mutation (Adam et al., 2013). Under the conditions of elevated fumarate, argininosuccinate is generated from arginine and fumarate by the reversed activity of the urea cycle enzyme argininosuccinate lyase (Zheng et al., 2013). We found that argininosuccinate is produced at high levels in Fh1-deficient c-Kit+ cells (Fig. 2 F). Furthermore, when accumulated at high levels, fumarate modifies cysteine residues in many proteins, forming S-(2-succinyl)-cysteine (2SC; Alderson et al., 2006; Adam et al., 2011; Bardella et al., 2011; Ternette et al., 2013). Fh1-deficient c-Kit+ cells exhibited high immunoreactivity for 2SC (Fig. 2 G). Thus, primitive hematopoietic cells lacking Fh1 have compromised maximal mitochondrial respiration, display increased glycolysis, fail to maintain normal ATP production upon inhibition of glycolysis, and accumulate high levels of fumarate resulting in excessive protein succination.

Efficient fumarate metabolism is essential for HSC maintenance and multilineage hematopoiesis

Mechanistically, the phenotypes observed upon Fh1 deletion could result from the genetic block in the TCA cycle or the accumulation of cellular fumarate (Pollard et al., 2007; Adam et al., 2011). To differentiate between these two mechanisms, we used mice ubiquitously expressing a human cytoplasmic isoform of FH (FHCyt, which lacks the mitochondrial targeting sequence and therefore is excluded from the mitochondria; Adam et al., 2013). FHCyt does not restore defects in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism but normalizes levels of total cellular fumarate (O’Flaherty et al., 2010; Adam et al., 2013). Although primitive hematopoietic cells from FLs of Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre embryos had normal mitochondrial membrane potential (not depicted), they displayed defective maximal respiration (Fig. 2 A) and impaired compensatory mitochondrial ATP production upon inhibition of glycolysis (Fig. 2 B, right), as well as an increase in ECAR (Fig. 2 D) similar to Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FL cells. Furthermore, primitive Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre FL cells had significantly reduced levels of cellular fumarate (Fig. 2 E) and argininosuccinate (Fig. 2 F) and undetectable immunoreactivity to 2SC (Fig. 2 G), indicating that the biochemical consequences of fumarate accumulation were largely abolished by the FHCyt transgene expression. Although FHCyt transgene decreased overall cellular levels of fumarate, argininosuccinate, and succinated proteins, we cannot exclude the possibility that fumarate is elevated in mitochondria and contributes to the impairment of mitochondrial function in the absence of mitochondrial Fh1. Collectively, although cells from Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre FLs displayed impaired maximal respiration, they had cellular fumarate levels comparable with control cells.

Notably, Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios (Table S3) and matured to adulthood without any obvious defects. BM cells from adult Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre mice efficiently generated myeloid colonies (Fig. 2 H), had normal BM cellularity (Fig. 2 I), and displayed multilineage hematopoiesis (Fig. 2, J and K), despite reduced numbers of B cells (Fig. 2 K). Furthermore, they had unaffected numbers of LK myeloid progenitor cells (Fig. 2 L) and increased numbers of LSK cells (Fig. 2 M) and HSCs (Fig. 2 N). Therefore, it is critical that HSCs and/or primitive progenitor cells efficiently metabolize fumarate to sustain hematopoietic differentiation. Finally, HSCs that acquire mitochondrial Fh1 deficiency (which abolishes maximal mitochondrial respiration) shortly after their emergence manage to survive, expand in the FL, colonize the BM, and sustain steady-state multilineage hematopoiesis, implying that mitochondrial Fh1 is largely dispensable for these processes.

Mitochondrial Fh1 deficiency compromises HSC self-renewal

To stringently test the long-term self-renewal capacity of HSCs lacking mitochondrial Fh1, we performed serial transplantation assays. We transplanted 100 HSCs from FLs of Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, and control 14.5-dpc embryos together with 200,000 support BM cells. Whereas Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre HSCs failed to repopulate the recipients, Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre HSCs contributed to primitive and more mature hematopoietic compartments of the recipient mice (Fig. 3 A). Primary recipients of Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre HSCs displayed efficient myeloid lineage reconstitution, whereas B and T lymphoid–lineage reconstitution was less robust (Fig. 3 B), suggesting that mitochondrial Fh1 is required for lymphoid cell differentiation or survival. Next, we sorted BM LSK cells from the primary recipients and retransplanted them into secondary recipients. Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre HSCs failed to contribute to the BM hematopoietic compartments of the recipients 20 wk after transplantation (Fig. 3 C). Therefore, HSCs lacking mitochondrial Fh1 display progressive loss of self-renewal potential upon serial transplantation.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial Fh1 is essential for HSC self-renewal. (A–C) 100 FL HSCs were transplanted into lethally irradiated 8–10-wk-old C57BL/6 CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice together with 2 × 105 CD45.1+ syngeneic competitor BM cells. The primary recipients were analyzed 20 wk after transplantation. 2,000 CD45.2+LSK cells were sorted from their BM and transplanted into secondary recipients together with competitor BM cells. Secondary recipients were analyzed 20 wk after transplantation. (A) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the Lin+, Lin−, LK, LSK, and HSC compartments in the BM of primary recipients. n = 4–5 recipients per donor. (B) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the monocyte, neutrophil, B cell, and T cell compartments in the PB of primary recipients. n = 4–5 recipients per donor. Number of donors used in A and B: control, n = 6; Fh1+/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 2; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 2; control;FHCyt, n = 6; Fh1+/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 3; Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 3. (C) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the Lin+, Lin−, LK, LSK, and HSC compartments in the BM of the secondary recipients. n = 4–5 recipients per donor. Number of donors: control, n = 3; control;FHCyt, n = 4; Fh1+/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 2; Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre, n = 3. Data are mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Hematopoietic defects upon Fh1 deletion are not caused by oxidative stress or the activation of Nrf2-dependent pathways

Because elevated cellular fumarate is a major cause of hematopoietic defects in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs, we next explored potential mechanisms through which fumarate impairs FL hematopoiesis. In nonhematopoietic tissues, fumarate succinates cysteine residues of biologically active molecules (including glutathione [GSH]; Sullivan et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2015) and numerous proteins (Adam et al., 2011; Ternette et al., 2013). Elevated fumarate causes oxidative stress by succinating GSH and, thus, generating succinic GSH and depleting the GSH pool (Sullivan et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2015). We found that reactive oxygen species (ROS) were modestly increased in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FL c-Kit+ cells compared with control cells (Fig. 4 A). The quantity of succinic GSH was elevated in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FL c-Kit+ cells (Fig. 4 B), but succinic GSH constituted only ∼1.5% of the total pool of GSH species (Fig. 4 C). Furthermore, we found that administration of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to timed-mated pregnant females did not rescue the reduced FL cellularity (not depicted) and failed to reverse decreased numbers of Lin+ FL cells (Fig. 4 D). Finally, HSCs sorted from NAC-treated Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs failed to reconstitute hematopoiesis in NAC-treated recipient mice (Fig. 4 E). Therefore, oxidative stress caused by GSH depletion does not cause hematopoietic defects resulting from fumarate accumulation.

Figure 4.

Molecular consequences of Fh1 deletion in primitive hematopoietic cells. (A) Intracellular ROS in FL c-Kit+ cells. The mean of mean fluorescence intensities ± SEM is shown. Control, n = 6; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 3. (B and C) GSH species in 14.5-dpc FL c-Kit+ cells measured using LC-MS. Succinic GSH levels (arbitrary units; B) and percentage of Succinic GSH within the total GSH species (C) are shown. Control, n = 6; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 3. (D and E) Pregnant females were treated with NAC administered 7 d before the embryo harvest. (D) Lin+ cell numbers in 14.5-dpc FLs. Control, n = 15; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 6; control + NAC, n = 4; Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre + NAC, n = 4. (E) 600,000 total FL cells of 14.5-dpc embryos from NAC-treated pregnant females were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice together with 200,000 CD45.1+ competitor BM cells. Recipients were continuously treated with NAC. Data represent percentage of donor-derived CD45.2+ cells in PB 3 wk after transplantation. n = 10–11 recipients per genotype. n = 4 donors per genotype. (F) GSEA showing that the Nrf2 signature is not significantly affected in Fh1-deficient (Fh1 KO) FL Lin−c-Kit+ cells. FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score. (G) Western blots for Hif-1α and β-actin in c-Kit+ cells from 14.5-dpc FLs. n = 3 per genotype. CoCl2-treated FL c-Kit+ cells were used as a positive control for Hif-1α. Asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. (H) Total FL cellularity and total number of Lin+ cells and HSCs in 14.5-dpc FLs. Fh1fl/fl;Hif-1α+/+, n = 12; Fh1fl/fl;Hif-1α+/+;Vav-iCre, n = 9; Fh1fl/fl;Hif-1αfl/fl, n = 6; Fh1+/fl;Hif-1αfl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 5; Fh1fl/fl;Hif-1αfl/fl;Vav-iCre, n = 4. (I) Western blot for H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3, and total H3 in 14.5-dpc FL c-Kit+ cells. n = 3 per genotype. (J) Quantification of the data (normalized to total H3) shown in panel I. n = 3 per genotype. (K) Biological processes (presented as –log10 [p-value]) that are enriched in up-regulated and down-regulated genes in Fh1-deficient FL Lin−c-Kit+ cells versus control cells. Analysis was performed using the Gene Ontology Consortium database. The dashed gray line indicates P = 0.05. (L) Signature enrichment plots from GSEA analyses using unfolded protein response, apoptosis in response to ER stress, and protein translation signature gene sets. (F, K, and L) Gene expression analysis was performed using Lin−c-Kit+ cells from three Fh1fl/fl (WT) and four Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre (Fh1 KO) embryos. Data are mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Loss of Fh1 in renal cysts is associated with up-regulation of the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response pathway because of fumarate-mediated succination of Keap1, which normally promotes Nrf2 degradation (Adam et al., 2011). However, the analyses of global gene expression profiling of FL Lin−c-Kit+ primitive hematopoietic cells from 14.5-dpc Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and control embryos revealed no significant enrichment for Nrf2 signature (Fig. 4 F). Thus, the activation of the Nrf2-dependent pathways is not responsible for defective hematopoiesis in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs.

Fh1 deficiency in primitive hematopoietic cells has no impact on the Hif-1–dependent pathways and does not affect global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels

Fumarate is known to competitively inhibit 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)–dependent oxygenases including Hif prolyl hydroxylase Phd2 resulting in stabilization of Hif-1α (Adam et al., 2011). Given that Phd2 deletion and stabilization of Hif-1α results in HSC defects (Takubo et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2013), we asked whether elevated fumarate increases the Hif-1α protein levels upon Fh1 deletion in primitive hematopoietic cells. We found that Hif-1α protein was undetectable in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and control FL c-Kit+ cells (Fig. 4 G), and additional deletion of Hif-1α in Fh1-deficient embryos failed to rescue embryonic lethality (not depicted), restore total FL cellularity, reverse decreased FL Lin+ cell numbers, or normalize elevated numbers of FL HSCs (Fig. 4 H). Thus, Hif-1α is not involved in generating hematopoietic defects in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs. Given that fumarate can inhibit the Tet family of 5-methylcytosine hydroxylases (Xiao et al., 2012), we measured the levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and control c-Kit+ cells and did not find any differences (not depicted), suggesting that fumarate-mediated Tet inhibition does not play a major role in generating hematopoietic defects in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FLs.

Fh1 deletion results in increased histone H3 trimethylation in primitive hematopoietic cells

Emerging evidence indicates that 2OG-dependent JmjC domain–containing histone demethylases (KDMs) play important roles in HSC biology and hematopoiesis (Stewart et al., 2015; Andricovich et al., 2016). Given that fumarate inhibits enzymatic activity of KDMs (Xiao et al., 2012), we examined the abundance of H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3 in nuclear extracts from FL c-Kit+ cells isolated from 14.5-dpc Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and control embryos. Western blot analyses revealed an increase in levels of H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3 but not H3K4me3 in Fh1-deficient cells (Fig. 4, I and J). Although these data suggest that Fh1 deficiency results in enhanced trimethylation of H3, the identity of KDMs that are inhibited by fumarate and the causal roles for increased H3 trimethylation in mediating HSC and hematopoietic defects upon Fh1 deletion remain to be elucidated.

Fh1 deletion promotes a gene expression signature that facilitates hematopoietic defects

To understand the molecular signatures associated with Fh1 deficiency, we performed gene expression profiling of FL Lin−c-Kit+ primitive hematopoietic cells from Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre and control embryos. We found that genes up-regulated in Fh1-deficient cells are highly enriched in categories related to apoptosis in response to ER stress, protein metabolic process/protein translation, and unfolded protein response (Fig. 4, K and L). Down-regulated genes are enriched in pathways related to heme biosynthesis, erythroid and myeloid function, and the cell cycle (Fig. 4 K). Although further detailed work will be needed to experimentally verify this, we propose that enhanced ER stress, unfolded protein response, and increased protein translation (which are known to contribute to HSC depletion and hematopoietic failure; Miharada et al., 2014; Signer et al., 2014; van Galen et al., 2014) may be responsible for hematopoietic defects upon Fh1 deletion.

Fh1 deficiency abolishes leukemic transformation and LIC functions

Although FH is a tumor suppressor (i.e., FH mutations result in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal-cell cancer) and fumarate is proposed to function as an oncometabolite (Yang et al., 2013), the role of FH in leukemic transformation remains unknown. Given that human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells express high levels of FH protein (López-Pedrera et al., 2006; Elo et al., 2014) and enzymatic activity of FH is increased in AML samples compared with cells from normal controls (Tanaka and Valentine, 1961), we next investigated the role for Fh1 in leukemic transformation. We used a mouse model of AML in which the development and maintenance of LICs is driven by Meis1 and Hoxa9 oncogenes (Wang et al., 2010; Vukovic et al., 2015). Meis1 and Hoxa9 are frequently overexpressed in several human AML subtypes (Lawrence et al., 1999; Drabkin et al., 2002), and their overexpression in mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells generates self-renewing LICs (Kroon et al., 1998). In the Meis1/Hoxa9 model used here, the FL LSK or c-Kit+ cell populations are transduced with retroviruses expressing Meis1 and Hoxa9 and are serially replated, generating a preleukemic cell population, which, upon transplantation to primary recipients, develops into LICs causing AML. LICs are defined by their capacity to propagate AML with short latency in secondary recipients (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006; Yeung et al., 2010; Vukovic et al., 2015). We found that Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre FL stem and progenitor cells transduced with Meis1/Hoxa9 (Fig. 5 A) failed to generate colonies in methylcellulose (Fig. 5 B). To corroborate these findings, we used retroviruses expressing MLL fusions which are frequently found in acute monoblastic leukemia (AML M5) and are associated with an unfavorable prognosis in AML, namely MLL-ENL (fusion oncogene resulting from t[11;19]) and MLL-AF9 (resulting from t[9;11]; Krivtsov and Armstrong, 2007; Lavallée et al., 2015). We also used AML1-ETO9a, a splice variant of AML1-ETO that is frequently expressed in t(8;21) patients with AML M2, and its high expression correlates with poor AML prognosis (Jiao et al., 2009). MLL fusions and AML1-ETO9a drive leukemogenesis through distinct pathways and are frequently used to transform mouse hematopoietic cells (Zuber et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2011; Velasco-Hernandez et al., 2014). We found that Fh1-deficient cells transduced with MLL-ENL, MLL-AF9, and AML1-ETO9a were unable to generate colonies (Fig. 5 B), indicating the requirement for Fh1 in in vitro transformation. Next, we determined the impact of Fh1 deletion on the colony formation capacity of preleukemic cells (Fig. 5 C). We transduced Fh1+/+ and Fh1fl/fl FL LSK cells with Meis1 and Hoxa9 retroviruses, and after three rounds of replating, we infected the transformed cells with Cre lentiviruses. Fh1fl/fl cells expressing Cre failed to generate colonies in CFC assays (Fig. 5 D). Thus, Fh1 deletion inhibits the generation of preleukemic cells and abolishes their clonogenic capacity.

Figure 5.

Fh1 is required for leukemic transformation. (A) 14.5-dpc FL c-Kit+ cells were transduced with Meis1/Hoxa9, MLL-AF9, MLL-ENL, and AML1-ETO9a retroviruses and plated into methylcellulose. (B) Colony counts 6 d after plating are shown. n = 4–5 per genotype. (C) Fh1+/+ and Fh1fl/fl (without Vav-iCre) FL LSK cells were co-transduced with Meis1 and Hoxa9 retroviruses and serially replated. The cells were subsequently infected with a bicistronic lentivirus expressing iCre and a Venus reporter. Venus+ cells were plated into methylcellulose. In parallel, Fh1+/+ and Fh1fl/fl preleukemic cells were transplanted into recipient mice. LICs (CD45.2+c-Kit+ cells) were sorted from the BM of leukemic recipients, transduced with Cre lentivirus, and plated into methylcellulose. (D) Number of colonies generated by Cre-expressing preleukemic cells. n = 3 per genotype. (E) Number of colonies generated by Cre-expressing LICs. n = 3 per genotype. (F) Relative levels of FH mRNA (normalized to ACTB) in untransduced THP-1 cells and THP-1 cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing scrambled shRNA (Scr shRNA) and three different shRNAs targeting FH (FH shRNA1, FH shRNA2, and FH shRNA3). n = 3. (G) Western blot for FH and β-actin in THP-1 cells described in Fig. 5 F. (H) Apoptosis assays performed with THP-1 cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing scrambled shRNA, FH shRNA1, and FH shRNA3. The graph depicts the percentage of annexin V+DAPI− cells in early apoptosis and annexin V+DAPI+ in late apoptosis. n = 4. (I) CFC assays with THP-1 cells expressing scrambled shRNA, FH shRNA1, and FH shRNA3. n = 5. Data are mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

To determine the requirement for Fh1 in LICs, LSK cells from Fh1+/+ and Fh1fl/fl FLs were transduced with Meis1 and Hoxa9 retroviruses and transplanted into primary recipients (Fig. 5 C). LICs isolated from leukemic primary recipient mice were infected with Cre lentivirus and plated into methylcellulose. We found that Fh1-deficient LICs were unable to generate colonies (Fig. 5 E). Next, we investigated the requirement for FH in human established leukemic cells by knocking down the expression of FH in human AML (M5) THP-1 cells harboring MLL-AF9 translocation. We generated lentiviruses expressing three independent short hairpins (i.e., FH shRNA 1–3) targeting FH and a scrambled shRNA sequence. Based on knockdown efficiency (Fig. 5, F and G), we selected FH shRNA1 and FH shRNA3 for further experiments. FH knockdown increased apoptosis of THP-1 cells (Fig. 5 H) and decreased their ability to form colonies (Fig. 5 I). Therefore, Fh1 is required for survival of both mouse LICs and human established leukemic cells. Finally, we conclude that the tumor suppressor functions of FH are tissue specific and do not extend to hematopoietic cells.

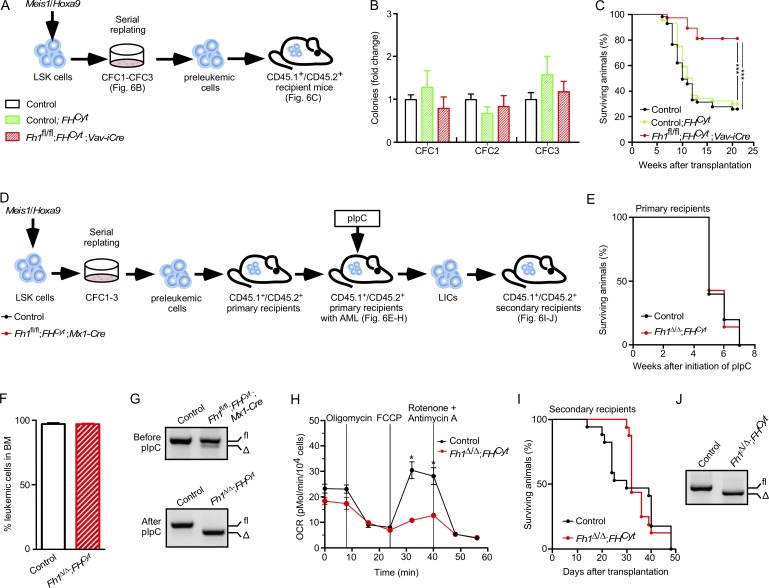

Mitochondrial Fh1 is necessary for AML development but is not required for disease maintenance

Next, we investigated the impact of mitochondrial Fh1 deficiency on in vitro transformation and development and maintenance of LICs (Fig. 6, A–C). FL Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre cells transduced with Meis1/Hoxa9 retroviruses had normal serial replating capacity (Fig. 6 B), and the established preleukemic cells had normal proliferative capacity and cell-cycle status (not depicted). Thus, elevated fumarate is largely responsible for the inability of Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre stem and progenitor cells to undergo in vitro transformation. To establish the requirement for mitochondrial Fh1 in AML development in vivo, we transplanted control (Fh1fl/fl), control;FHCyt, and Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre Meis1/Hoxa9-transduced preleukemic cells into sublethally irradiated recipient mice (Fig. 6 A). We found that the percentage of recipients of Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre cells that developed terminal AML was significantly reduced (and the disease latency was extended) compared with recipients of control and control;FHCyt cells (Fig. 6 C). Finally, OCR measurements in LICs sorted from those recipients of Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre cells that succumbed to AML revealed that Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre LICs had defective maximal mitochondrial respiration compared with control and control;FHCyt LICs (not depicted). Thus, mitochondrial Fh1 is required for efficient generation of LICs and AML development in a Meis1/Hoxa9-driven model of leukemogenesis.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial Fh1 is necessary for efficient leukemia establishment but is not required for AML propagation. (A) Control, Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt (i.e., Control;FHCyt), and Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Vav-iCre FL LSK cells were co-transduced with Meis1 and Hoxa9 retroviruses and serially replated. 100,000 c-Kit+ preleukemic cells were transplanted into sublethally irradiated recipient mice. (B) CFC counts at each replating. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 per genotype. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of primary recipient mice. n = 8–10 recipients per genotype and 4 donors per genotype. ***, P < 0.001 (log-rank [Mantel-Cox] test). (D) Control and Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Mx1-Cre FL LSK cells were co-transduced with Meis1 and Hoxa9 retroviruses and serially replated. The resultant preleukemic cells were transplanted into sublethally irradiated recipients. Once leukemic CD45.2+ cells reached 20% in the PB of recipient mice, the recipients received eight doses of pIpC. 10,000 LICs (CD45.2+c-Kit+) from primary recipients were transplanted into secondary recipients. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of primary recipient mice. pIpC treatment was initiated 5 wk after transplantation. n = 5–7 recipients per genotype. (F) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in BM of primary recipient mice with terminal leukemia. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 5–7 recipients per genotype. (G) Genomic PCR assessing Fh1 deletion before pIpC (top) and after pIpC (bottom) treatment. Δ, excised allele; fl, undeleted conditional allele. (H) OCR in LICs isolated from the BM of primary recipients treated with pIpC. OCR was assayed as described in Fig 2 A. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3–5. *, P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test). (I) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of secondary recipients transplanted with LICs sorted from leukemic primary recipients. n = 10 per genotype. (J) Representative gel showing PCR amplification of genomic DNA from the total BM of secondary recipients with terminal leukemia.

Given that mitochondrial Fh1 was important for leukemia initiation, we next asked whether inducible deletion of mitochondrial Fh1 from leukemic cells impacts on leukemia propagation and LIC maintenance (Fig. 6, D–J). We transduced control and Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Mx1-Cre FL LSK cells with Meis1/Hoxa9 retroviruses, and after serial replating, the resultant preleukemic cells were transplanted into primary recipient mice (Fig. 6 D). Upon disease diagnosis (i.e., 20% of CD45.2+ leukemic cells in the PB), the mice received eight pIpC doses (Fig. 6 D). Recipients of both control and Fh1fl/fl;FHCyt;Mx1-Cre cells equally succumbed to terminal AML (Fig. 6, E and F). After confirming efficient Fh1 deletion (Fig. 6 G) and defective maximal respiration (Fig. 6 H), we isolated LICs from the BM of leukemic primary recipient mice and transplanted them into secondary recipients. We found that LICs lacking mitochondrial Fh1 and control LICs equally efficiently caused leukemia in secondary recipients (Fig. 6, I and J). Thus, mitochondrial Fh1 is necessary for efficient LIC generation but is not required for their ability to efficiently propagate Meis1/Hoxa9-driven leukemia.

Discussion

By performing genetic dissection of multifaceted functions of the key metabolic gene Fh1, we have uncovered a previously unknown requirement for fumarate metabolism in the hematopoietic system. We conclude that efficient utilization of intracellular fumarate is required to prevent its potentially toxic effects and is central to the integrity of HSCs and hematopoietic differentiation. Furthermore, although fumarate promotes oncogenesis in the kidney (Yang et al., 2013), it has the opposite effect in the hematopoietic system, i.e., it inhibits leukemic transformation. Our data, indicating a detrimental impact of fumarate on hematopoiesis, collectively with fumarate’s functions as an oncometabolite in nonhematopoietic tumors (Yang et al., 2013), or a protective role within the myocardium (Ashrafian et al., 2012), highlight distinct functions of fumarate in different tissues.

Elevated fumarate within the hematopoietic system is likely to perturb multiple biochemical mechanisms. Fumarate is known to inhibit 2OG-dependent oxygenases, including HIF-hydroxylase Phd2 (Hewitson et al., 2007), the Tet enzymes, and KDMs (Xiao et al., 2012), and as a consequence, tumor cells with FH mutations have increased HIF-1α stability and display a hypermethylator phenotype (Isaacs et al., 2005; Pollard et al., 2007; Letouzé et al., 2013; Castro-Vega et al., 2014). We found that hematopoietic defects resulting from elevated fumarate are most likely generated through the Hif-1–independent and Tet-independent mechanisms. However, consistent with the ability of fumarate to inhibit KDMs, we found that levels of H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3 were elevated in primitive hematopoietic cells lacking Fh1. Although detailed underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated, we propose that elevated fumarate may cause the observed phenotypes by inhibiting these KDMs that are essential for normal hematopoiesis and HSC functions, including KDM5B (Stewart et al., 2015) and KDM2B (Andricovich et al., 2016).

Fumarate is also known to cause succination of cysteine residues of numerous proteins (e.g., Keap1, which normally promotes Nrf2 degradation; Adam et al., 2011; Ternette et al., 2013) or GSH (Sullivan et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2015). However, our data indicated that hematopoietic defects upon Fh1 deletion are unlikely to be mediated by Nrf2 activation or GSH depletion. Given our findings that Fh1-deficient cells have increased signatures of ER stress and unfolded protein response, it will be of high interest to determine whether increased global protein succination in Fh1-deficient cells results in protein misfolding in HSCs, leading to the activation of unfolded protein response, which is detrimental to HSC integrity (van Galen et al., 2014).

Fh1 deletion with the simultaneous reexpression of cytosolic FH allowed us to investigate the genetic requirement for mitochondrial Fh1 in long-term HSC functions. Our serial transplantation assays revealed that mitochondrial Fh1 was essential for HSC self-renewal, indicating a key role for an intact TCA cycle in HSC maintenance. Intriguingly, although mitochondrial Fh1 deficiency did not affect myeloid output under steady-state conditions and upon transplantation, the lack of mitochondrial Fh1 had an impact on the lymphoid output. These data imply differential requirements for the intact TCA cycle in lineage commitment and/or differentiation of primitive hematopoietic cells, meriting further investigations.

Both self-renewing HSCs and LICs are thought to rely heavily on glycolysis while they suppress the TCA cycle (Simsek et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014). We used the genetic mitochondrial Fh1 deficiency to examine the differential requirement for mitochondrial Fh1 in long-term HSC self-renewal and the development and maintenance of LICs. We conclude that self-renewing HSCs critically require intact mitochondrial Fh1 and the capacity for maximal mitochondrial respiration to maintain their pool. However, although mitochondrial Fh1 was necessary for LIC development, it had no impact on maintenance of LICs. Thus, we reveal a differential requirement for the mitochondrial TCA enzyme Fh1 in normal hematopoiesis and Meis1/Hoxa9-driven leukemia propagation. The discovery of mechanisms underlying different metabolic requirements in HSCs and LICs represents a key area for future investigations.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mice were on a C57BL/6 genetic background. Fh1fl/fl (Pollard et al., 2007), Hif-1αfl/fl (Ryan et al., 2000; Vukovic et al., 2016), and V5-FHCyt (referred to as FHCyt; Adam et al., 2013) were described previously. Vav-iCre and Mx1-Cre were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All transgenic and knockout mice were CD45.2+. Congenic recipient mice were CD45.1+/CD45.2+. All experiments on animals were performed under UK Home Office authorization.

Flow cytometry

All BM and FL samples were stained and analyzed as described previously (Kranc et al., 2009; Mortensen et al., 2011; Guitart et al., 2013; Vukovic et al., 2016). BM cells were obtained by crushing tibias and femurs with a pestle and mortar. FL cells were obtained by mashing the tissue through a 70-µm strainer. Single-cell suspensions from BM, FL, or PB were incubated with Fc block and then stained with antibodies. For HSC analyses, after incubation with Fc block, unfractionated FL or BM cell suspensions were stained with lineage markers containing biotin-conjugated anti-CD4, anti-CD5, anti-CD8a, anti-CD11b (not used in FL analyses), anti-B220, anti–Gr-1, and anti-Ter119 antibodies together with APC-conjugated anti–c-Kit, APC/Cy7-conjugated anti–Sca-1, PE-conjugated anti-CD48, and PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD150 antibodies. Then, biotin-conjugated antibodies were stained with Pacific blue–conjugated or PerCP-conjugated streptavidin. To distinguish CD45.2+ donor–derived HSCs in recipient mice, FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.1 and Pacific blue–conjugated anti-CD45.2 antibodies were included in the antibody cocktail. The multilineage reconstitution of recipient mice was determined by staining the BM or PB cell suspensions of the recipient mice with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.1, Pacific blue–conjugated anti-CD45.2, PE-conjugated anti-CD4 and -CD8a, PE/Cy7-conjugated anti–Gr-1, APC-conjugated anti-CD11b, APC-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD19, and anti-B220. In all analyses, 7-AAD or DAPI was used for dead cell exclusion. Flow cytometry analyses were performed using an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD). Cell sorting was performed on a FACSAria Fusion cell sorter (BD).

CFC assays

CFC assays were performed using MethoCult (M3434; STEMCELL Technologies). Two replicates were used per group in each experiment. Colonies were tallied at day 10.

Leukemic transformation

LSK cells were sorted from FLs of 14.5-dpc embryos after c-Kit (CD117) enrichment using magnetic-activated cell-sorting columns (Miltenyi Biotec). 10,000 LSK cells were simultaneously transduced with mouse stem cell virus (MSCV)–Meis1a-puro and MSCV–Hoxa9-neo retroviruses and subsequently subjected to three rounds of CFC assays in MethoCult (M3231) supplemented with 20 ng/ml stem cell factor, 10 ng/ml IL-3, 10 ng/ml IL-6, and 10 ng/ml granulocyte/macrophage stem cell factor. Colonies were counted 6–7 d after plating, and 2,500 cells were replated. Similarly, 200,000 FL c-Kit+ cells were transduced with MSCV–AML1-ETO9a-neo, MSCV–MLL-AF9-neo, or MSCV–MLL-ENL-neo and subsequently plated into methylcellulose.

Transplantation assays

Lethal irradiation of CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice was achieved using a split dose of 11 Gy (two doses of 5.5 Gy administered at least 4 h apart) at a mean rate of 0.58 Gy/min using a Cesium 137 irradiator (GammaCell 40; Best Theratronics). For sublethal irradiation, the recipient mice received a split dose of 7 Gy (two doses of 3.5 Gy at least 4 h apart).

For primary transplantations, 100 HSCs (LSKCD48−CD150+CD45.2+) sorted from FLs of 14.5-dpc embryos or 200,000 unfractionated FL cells were mixed with 200,000 support CD45.1+ BM cells and injected into lethally irradiated (11 Gy delivered in a split dose) CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice. For secondary transplantations, 2,000 CD45.2+ LSK cells sorted from BM of primary recipients were mixed with 200,000 support CD45.1+ wild-type BM cells and retransplanted. For adult BM transplantations, 500,000 CD45.2+ BM cells were mixed with 500,000 support CD45.1+ wild-type BM cells and injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice. All recipient mice were analyzed 18–20 wk after transplantation, unless otherwise stated.

For leukemia induction, 100,000 Meis-1/Hoxa9-transduced c-Kit+ cells were transplanted into CD45.1+/CD45.2+ sublethally irradiated (7 Gy delivered in a split dose) recipient mice. The mice were monitored for AML development. For secondary transplantation, 10,000 LICs (CD45.2+c-Kit+ cells) were sorted from BM of primary recipients and transplanted into secondary CD45.1+/CD45.2+ sublethally irradiated recipient mice.

Inducible Mx1-Cre–mediated gene deletion

Mice were injected intraperitoneally six to eight times every alternate day with 300 µg pIpC (GE Healthcare) as previously described (Kranc et al., 2009; Guitart et al., 2013).

Administration of NAC

Pregnant females received 30 mg/ml of NAC (Sigma-Aldrich) in drinking water (pH was adjusted to 7.2–7.4 with NaOH). For transplantation experiments, CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice were treated with 30 mg/ml NAC in drinking water 7 d before irradiation and remained under NAC treatment for the duration of the experiment. The water bottle containing NAC was changed twice per week.

Oxygen consumption assays

OCR measurements were made using a Seahorse XF-24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) and the XF Cell Mito Stress Test kit as previously described (Wang et al., 2014). In brief, c-Kit+ cells from FLs of 14.5-dpc embryos were plated in XF-24 microplates precoated with cell-tak (BD) at 250,000 cells per well in XF Base medium supplemented with 2 mM pyruvate and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4. OCR was measured three times every 6 min for basal value and after each sequential addition of oligomycin (1 µM), FCCP (1 µM), and finally concomitant rotenone and antimycin A (1 µM). Oxygen consumption measurements were normalized to cell counts performed before and after each assay.

Metabolite detection by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Metabolites from c-Kit+ cells from FLs of 14.5-dpc embryos were extracted into 50% methanol/30% acetonitrile and measured as previously described (Adam et al., 2013).

Western blotting

Protein extracted from FL c-Kit+ cells of 14.5-dpc embryos was subjected to a 10% SDS–PAGE and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and immunoblotted with anti-Fh1, anti–2-SC, and anti–Hif-1α as previously described (Adam et al., 2011; Bardella et al., 2012). Anti-H3K4me3 (07-473; EMD Millipore), anti-H3K9me3 (ab8898; Abcam), anti-H3K27me3 (07-449; EMD Millipore), and anti-H3K36me3 (ab9050; Abcam) were used to determine levels of trimethylated H3. Anti-actin (A5316; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-tubulin (2146S; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-H3 (ab1791; Abcam) immunoblots were used as loading controls.

RT–quantitative PCR

Gene expression analyses were performed as described previously (Kranc et al., 2009; Mortensen et al., 2011; Guitart et al., 2013). Differences in input cDNA were normalized with Actb (β-actin) expression.

ATP production

10,000 c-Kit+ cells from FLs of 14.5-dpc embryos were cultured in DMEM supplemented with either 25 mM glucose or 25 mM galactose. At 0 and 24 h after incubation, the cells were lysed, and ATP content was measured by luminescence using CellTiterGlo Assay (Promega).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

50,000 FL c-Kit+ cells from 14.5-dpc embryos were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in 25 nM tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (T-668; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed using the LSRFortessa flow cytometer.

Gene expression profiling and bioinformatics analyses

RNA from sorted FL Lin−c-Kit+ cells was isolated by standard phenol/chloroform extraction. cDNA was synthesized from 50 ng of total RNA using the Ambion WT Expression kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Labeled, fragmented cDNA (GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling and Controls kit; Affymetrix) was hybridized to Mouse Gene 2.0 arrays for 16 h at 45°C and 60 rpm (GeneChip Hybridization, Wash, and Stain kit; Affymetrix). Arrays were washed and stained using the Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix) and scanned using a GeneArray Scanner (3000 7G; Hewlett-Packard). The microarray gene expression data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database under accession no. E-MTAB-5425.

For bioinformatics analyses, a total of seven arrays (n = 3 Fh1fl/fl; n = 4 Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre) were quality control analyzed using the arrayQualityMetrics package in Bioconductor. Normalization of the 29,638 features across all arrays was achieved using the robust multiarray average expression measure. Pairwise group comparisons were undertaken using linear modeling (LIMMA package in Bioconductor). Subsequently, empirical Bayesian analysis was applied, including vertical (within a given comparison) p-value adjustment for multiple testing, which controls for false discovery rate.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Gene expression differences were ranked by difference of log expression values, and this ranking was used to perform GSEA (Subramanian et al., 2005) on gene lists in the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB; version 5.2). The following datasets were used for analyses presented in Fig. 4: (a) hallmark, unfolded protein response; (b) gene ontology, intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress; (c) reactome, translation; and (d) NFE2L2.V2.

shRNA-mediated FH knockdown

THP-1 cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs (shRNA1, 5′-TAATCCTGGTTTACTTCAGCG-3′ [TRCN0000052463]; shRNA2, 5′-AAGGTATCATATTCTATCCGG-3′ [TRCN0000052464]; shRNA3, 5′-TTTATTAACATGATCGTTGGG-3′ [TRCN0000052465]; and shRNA Scr, 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTT-3′; RNAi Consortium; GE Healthcare). Transduced THP-1 cells were grown in the presence of 5 µg/ml puromycin.

ROS analysis

c-Kit+ cells were stained with 2.5 nM CellROX (C10491; Thermo Fisher Scientific) based on the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed by FACS.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test unless stated otherwise. Kaplan-Meier survival curve statistics were determined using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Online supplemental material

Table S1 shows neutropenia in patients with recessive FH mutations. Table S2 shows hematopoiesis-specific Fh1 deletion results in embryonic lethality. Table S3 shows FHCyt rescues embryonic lethality in Fh1fl/fl;Vav-iCre mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Vladimir Benes and Jelena Pistolic from the Genomics Core facility of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (Heidelberg) for performing the gene expression profiling. We thank Fiona Rossi and Dr. Claire Cryer for their help with flow cytometry.

K.R. Kranc is a Cancer Research UK Senior Cancer Research Fellow. This project was funded by the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, Cancer Research UK, Bloodwise, Tenovus Scotland, and the Wellcome Trust’s Institutional Strategic Support Fund.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- AML

- acute myeloid leukemia

- CFC

- colony-forming cell

- dpc

- days postcoitum

- ECAR

- extracellular acidification rate

- Fh1

- fumarate hydratase

- FL

- fetal liver

- GSEA

- gene set enrichment analysis

- GSH

- glutathione

- HPC

- hematopoietic progenitor cell

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- LC-MS

- liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- LIC

- leukemia-initiating cell

- MSCV

- mouse stem cell virus

- NAC

- N-acetylcysteine

- OCR

- oxygen consumption rate

- pIpC

- polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- TCA

- tricarboxylic acid

References

- Adam J., Hatipoglu E., O’Flaherty L., Ternette N., Sahgal N., Lockstone H., Baban D., Nye E., Stamp G.W., Wolhuter K., et al. 2011. Renal cyst formation in Fh1-deficient mice is independent of the Hif/Phd pathway: roles for fumarate in KEAP1 succination and Nrf2 signaling. Cancer Cell. 20:524–537. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam J., Yang M., Bauerschmidt C., Kitagawa M., O’Flaherty L., Maheswaran P., Özkan G., Sahgal N., Baban D., Kato K., et al. 2013. A role for cytosolic fumarate hydratase in urea cycle metabolism and renal neoplasia. Cell Reports. 3:1440–1448. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson N.L., Wang Y., Blatnik M., Frizzell N., Walla M.D., Lyons T.J., Alt N., Carson J.A., Nagai R., Thorpe S.R., and Baynes J.W.. 2006. S-(2-Succinyl)cysteine: a novel chemical modification of tissue proteins by a Krebs cycle intermediate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 450:1–8. 10.1016/j.abb.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andricovich J., Kai Y., Peng W., Foudi A., and Tzatsos A.. 2016. Histone demethylase KDM2B regulates lineage commitment in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. J. Clin. Invest. 126:905–920. 10.1172/JCI84014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafian H., Czibik G., Bellahcene M., Aksentijević D., Smith A.C., Mitchell S.J., Dodd M.S., Kirwan J., Byrne J.J., Ludwig C., et al. 2012. Fumarate is cardioprotective via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Cell Metab. 15:361–371. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardella C., El-Bahrawy M., Frizzell N., Adam J., Ternette N., Hatipoglu E., Howarth K., O’Flaherty L., Roberts I., Turner G., et al. 2011. Aberrant succination of proteins in fumarate hydratase-deficient mice and HLRCC patients is a robust biomarker of mutation status. J. Pathol. 225:4–11. 10.1002/path.2932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardella C., Olivero M., Lorenzato A., Geuna M., Adam J., O’Flaherty L., Rustin P., Tomlinson I., Pollard P.J., and Di Renzo M.F.. 2012. Cells lacking the fumarase tumor suppressor are protected from apoptosis through a hypoxia-inducible factor-independent, AMPK-dependent mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:3081–3094. 10.1128/MCB.06160-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T., Chretien D., Poggi-Bach J., Doonan S., Rabier D., Letouzé P., Munnich A., Rötig A., Landrieu P., and Rustin P.. 1994. Mutation of the fumarase gene in two siblings with progressive encephalopathy and fumarase deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 93:2514–2518. 10.1172/JCI117261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Vega L.J., Buffet A., De Cubas A.A., Cascón A., Menara M., Khalifa E., Amar L., Azriel S., Bourdeau I., Chabre O., et al. 2014. Germline mutations in FH confer predisposition to malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23:2440–2446. 10.1093/hmg/ddt639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.W., Gerencser A.A., and Nicholls D.G.. 2009. Bioenergetic analysis of isolated cerebrocortical nerve terminals on a microgram scale: spare respiratory capacity and stochastic mitochondrial failure. J. Neurochem. 109:1179–1191. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06055.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J., Williams A., Skavdis G., Harker N., Coles M., Tolaini M., Norton T., Williams K., Roderick K., Potocnik A.J., and Kioussis D.. 2003. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:314–325. 10.1002/immu.200310005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabkin H.A., Parsy C., Ferguson K., Guilhot F., Lacotte L., Roy L., Zeng C., Baron A., Hunger S.P., Varella-Garcia M., et al. 2002. Quantitative HOX expression in chromosomally defined subsets of acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 16:186–195. 10.1038/sj.leu.2402354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo L.L., Karjalainen R., Ohman T., Hintsanen P., Nyman T.A., Heckman C.A., and Aittokallio T.. 2014. Statistical detection of quantitative protein biomarkers provides insights into signaling networks deregulated in acute myeloid leukemia. Proteomics. 14:2443–2453. 10.1002/pmic.201300460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrick D.A., Neilson A., and Beeson C.. 2008. Advances in measuring cellular bioenergetics using extracellular flux. Drug Discov. Today. 13:268–274. 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttgens B. 2015. Regulatory network control of blood stem cells. Blood. 125:2614–2620. 10.1182/blood-2014-08-570226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitart A.V., Subramani C., Armesilla-Diaz A., Smith G., Sepulveda C., Gezer D., Vukovic M., Dunn K., Pollard P., Holyoake T.L., et al. 2013. Hif-2α is not essential for cell-autonomous hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Blood. 122:1741–1745. 10.1182/blood-2013-02-484923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson K.S., Liénard B.M., McDonough M.A., Clifton I.J., Butler D., Soares A.S., Oldham N.J., McNeill L.A., and Schofield C.J.. 2007. Structural and mechanistic studies on the inhibition of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor hydroxylases by tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 282:3293–3301. 10.1074/jbc.M608337200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J.S., Jung Y.J., Mole D.R., Lee S., Torres-Cabala C., Chung Y.L., Merino M., Trepel J., Zbar B., Toro J., et al. 2005. HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell. 8:143–153. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao B., Wu C.F., Liang Y., Chen H.M., Xiong S.M., Chen B., Shi J.Y., Wang Y.Y., Wang J.H., Chen Y., et al. 2009. AML1-ETO9a is correlated with C-KIT overexpression/mutations and indicates poor disease outcome in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia-M2. Leukemia. 23:1598–1604. 10.1038/leu.2009.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuper M., Jastroch M., Yi C.X., Fischer-Posovszky P., Wabitsch M., Tschöp M.H., and Hofmann S.M.. 2014. Spare mitochondrial respiratory capacity permits human adipocytes to maintain ATP homeostasis under hypoglycemic conditions. FASEB J. 28:761–770. 10.1096/fj.13-238725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranc K.R., Schepers H., Rodrigues N.P., Bamforth S., Villadsen E., Ferry H., Bouriez-Jones T., Sigvardsson M., Bhattacharya S., Jacobsen S.E., and Enver T.. 2009. Cited2 is an essential regulator of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 5:659–665. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov A.V., and Armstrong S.A.. 2007. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7:823–833. 10.1038/nrc2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E., Krosl J., Thorsteinsdottir U., Baban S., Buchberg A.M., and Sauvageau G.. 1998. Hoxa9 transforms primary bone marrow cells through specific collaboration with Meis1a but not Pbx1b. EMBO J. 17:3714–3725. 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn R., Schwenk F., Aguet M., and Rajewsky K.. 1995. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 269:1427–1429. 10.1126/science.7660125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagadinou E.D., Sach A., Callahan K., Rossi R.M., Neering S.J., Minhajuddin M., Ashton J.M., Pei S., Grose V., O’Dwyer K.M., et al. 2013. BCL-2 inhibition targets oxidative phosphorylation and selectively eradicates quiescent human leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 12:329–341. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launonen V., Vierimaa O., Kiuru M., Isola J., Roth S., Pukkala E., Sistonen P., Herva R., and Aaltonen L.A.. 2001. Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:3387–3392. 10.1073/pnas.051633798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallée V.P., Baccelli I., Krosl J., Wilhelm B., Barabé F., Gendron P., Boucher G., Lemieux S., Marinier A., Meloche S., et al. 2015. The transcriptomic landscape and directed chemical interrogation of MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemias. Nat. Genet. 47:1030–1037. 10.1038/ng.3371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence H.J., Rozenfeld S., Cruz C., Matsukuma K., Kwong A., Kömüves L., Buchberg A.M., and Largman C.. 1999. Frequent co-expression of the HOXA9 and MEIS1 homeobox genes in human myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 13:1993–1999. 10.1038/sj.leu.2401578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letouzé E., Martinelli C., Loriot C., Burnichon N., Abermil N., Ottolenghi C., Janin M., Menara M., Nguyen A.T., Benit P., et al. 2013. SDH mutations establish a hypermethylator phenotype in paraganglioma. Cancer Cell. 23:739–752. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Pedrera C., Villalba J.M., Siendones E., Barbarroja N., Gómez-Díaz C., Rodríguez-Ariza A., Buendía P., Torres A., and Velasco F.. 2006. Proteomic analysis of acute myeloid leukemia: Identification of potential early biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Proteomics. 6:S293–S299. 10.1002/pmic.200500384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manesia J.K., Xu Z., Broekaert D., Boon R., van Vliet A., Eelen G., Vanwelden T., Stegen S., Van Gastel N., Pascual-Montano A., et al. 2015. Highly proliferative primitive fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells are fueled by oxidative metabolic pathways. Stem Cell Res. (Amst.). 15:715–721. 10.1016/j.scr.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miharada K., Sigurdsson V., and Karlsson S.. 2014. Dppa5 improves hematopoietic stem cell activity by reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Reports. 7:1381–1392. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen M., Soilleux E.J., Djordjevic G., Tripp R., Lutteropp M., Sadighi-Akha E., Stranks A.J., Glanville J., Knight S., Jacobsen S.-E.W., et al. 2011. The autophagy protein Atg7 is essential for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. J. Exp. Med. 208:455–467. 10.1084/jem.20101145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty L., Adam J., Heather L.C., Zhdanov A.V., Chung Y.L., Miranda M.X., Croft J., Olpin S., Clarke K., Pugh C.W., et al. 2010. Dysregulation of hypoxia pathways in fumarate hydratase-deficient cells is independent of defective mitochondrial metabolism. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19:3844–3851. 10.1093/hmg/ddq305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard P.J., Spencer-Dene B., Shukla D., Howarth K., Nye E., El-Bahrawy M., Deheragoda M., Joannou M., McDonald S., Martin A., et al. 2007. Targeted inactivation of fh1 causes proliferative renal cyst development and activation of the hypoxia pathway. Cancer Cell. 11:311–319. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan H.E., Poloni M., McNulty W., Elson D., Gassmann M., Arbeit J.M., and Johnson R.S.. 2000. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is a positive factor in solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 60:4010–4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass E., Blachinsky E., Karniely S., and Pines O.. 2001. Mitochondrial and cytosolic isoforms of yeast fumarase are derivatives of a single translation product and have identical amino termini. J. Biol. Chem. 276:46111–46117. 10.1074/jbc.M106061200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signer R.A., Magee J.A., Salic A., and Morrison S.J.. 2014. Haematopoietic stem cells require a highly regulated protein synthesis rate. Nature. 509:49–54. 10.1038/nature13035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek T., Kocabas F., Zheng J., Deberardinis R.J., Mahmoud A.I., Olson E.N., Schneider J.W., Zhang C.C., and Sadek H.A.. 2010. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 7:380–390. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.P., Franke K., Kalucka J., Mamlouk S., Muschter A., Gembarska A., Grinenko T., Willam C., Naumann R., Anastassiadis K., et al. 2013. HIF prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) is a critical regulator of hematopoietic stem cell maintenance during steady-state and stress. Blood. 121:5158–5166. 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.L., Yeung J., Zeisig B.B., Popov N., Huijbers I., Barnes J., Wilson A.J., Taskesen E., Delwel R., Gil J., et al. 2011. Functional crosstalk between Bmi1 and MLL/Hoxa9 axis in establishment of normal hematopoietic and leukemic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 8:649–662. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somervaille T.C., and Cleary M.L.. 2006. Identification and characterization of leukemia stem cells in murine MLL-AF9 acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 10:257–268. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein I., Peleg Y., Even-Ram S., and Pines O.. 1994. The single translation product of the FUM1 gene (fumarase) is processed in mitochondria before being distributed between the cytosol and mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4770–4778. 10.1128/MCB.14.7.4770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M.H., Albert M., Sroczynska P., Cruickshank V.A., Guo Y., Rossi D.J., Helin K., and Enver T.. 2015. The histone demethylase Jarid1b is required for hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in mice. Blood. 125:2075–2078. 10.1182/blood-2014-08-596734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., and Mesirov J.P.. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T., Takubo K., and Semenza G.L.. 2011. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 9:298–310. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan L.B., Martinez-Garcia E., Nguyen H., Mullen A.R., Dufour E., Sudarshan S., Licht J.D., Deberardinis R.J., and Chandel N.S.. 2013. The proto-oncometabolite fumarate binds glutathione to amplify ROS-dependent signaling. Mol. Cell. 51:236–248. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takubo K., Goda N., Yamada W., Iriuchishima H., Ikeda E., Kubota Y., Shima H., Johnson R.S., Hirao A., Suematsu M., and Suda T.. 2010. Regulation of the HIF-1α level is essential for hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 7:391–402. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takubo K., Nagamatsu G., Kobayashi C.I., Nakamura-Ishizu A., Kobayashi H., Ikeda E., Goda N., Rahimi Y., Johnson R.S., Soga T., et al. 2013. Regulation of glycolysis by Pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 12:49–61. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K.R., and Valentine W.N.. 1961. Fumarase activity of human leukocytes and erythrocytes. Blood. 17:328–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternette N., Yang M., Laroyia M., Kitagawa M., O’Flaherty L., Wolhulter K., Igarashi K., Saito K., Kato K., Fischer R., et al. 2013. Inhibition of mitochondrial aconitase by succination in fumarate hydratase deficiency. Cell Reports. 3:689–700. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson I.P., Alam N.A., Rowan A.J., Barclay E., Jaeger E.E., Kelsell D., Leigh I., Gorman P., Lamlum H., Rahman S., et al. Multiple Leiomyoma Consortium . 2002. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat. Genet. 30:406–410. 10.1038/ng849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregoning S., Salter W., Thorburn D.R., Durkie M., Panayi M., Wu J.Y., Easterbrook A., and Coman D.J.. 2013. Fumarase deficiency in dichorionic diamniotic twins. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 16:1117–1120. 10.1017/thg.2013.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Windt G.J., Everts B., Chang C.H., Curtis J.D., Freitas T.C., Amiel E., Pearce E.J., and Pearce E.L.. 2012. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+ T cell memory development. Immunity. 36:68–78. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Galen P., Kreso A., Mbong N., Kent D.G., Fitzmaurice T., Chambers J.E., Xie S., Laurenti E., Hermans K., Eppert K., et al. 2014. The unfolded protein response governs integrity of the haematopoietic stem-cell pool during stress. Nature. 510:268–272. 10.1038/nature13228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco-Hernandez T., Hyrenius-Wittsten A., Rehn M., Bryder D., and Cammenga J.. 2014. HIF-1α can act as a tumor suppressor gene in murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 124:3597–3607. 10.1182/blood-2014-04-567065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukovic M., Guitart A.V., Sepulveda C., Villacreces A., O’Duibhir E., Panagopoulou T.I., Ivens A., Menendez-Gonzalez J., Iglesias J.M., Allen L., et al. 2015. Hif-1α and Hif-2α synergize to suppress AML development but are dispensable for disease maintenance. J. Exp. Med. 212:2223–2234. 10.1084/jem.20150452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukovic M., Sepulveda C., Subramani C., Guitart A.V., Mohr J., Allen L., Panagopoulou T.I., Paris J., Lawson H., Villacreces A., et al. 2016. Adult hematopoietic stem cells lacking Hif-1α self-renew normally. Blood. 127:2841–2846. 10.1182/blood-2015-10-677138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Krivtsov A.V., Sinha A.U., North T.E., Goessling W., Feng Z., Zon L.I., and Armstrong S.A.. 2010. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in AML. Science. 327:1650–1653. 10.1126/science.1186624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.H., Israelsen W.J., Lee D., Yu V.W., Jeanson N.T., Clish C.B., Cantley L.C., Vander Heiden M.G., and Scadden D.T.. 2014. Cell-state-specific metabolic dependency in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Cell. 158:1309–1323. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman I.L., and Shizuru J.A.. 2008. The origins of the identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells, and their capability to induce donor-specific transplantation tolerance and treat autoimmune diseases. Blood. 112:3543–3553. 10.1182/blood-2008-08-078220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M., Yang H., Xu W., Ma S., Lin H., Zhu H., Liu L., Liu Y., Yang C., Xu Y., et al. 2012. Inhibition of α-KG-dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 26:1326–1338. 10.1101/gad.191056.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadava N., and Nicholls D.G.. 2007. Spare respiratory capacity rather than oxidative stress regulates glutamate excitotoxicity after partial respiratory inhibition of mitochondrial complex I with rotenone. J. Neurosci. 27:7310–7317. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0212-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Soga T., and Pollard P.J.. 2013. Oncometabolites: linking altered metabolism with cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 123:3652–3658. 10.1172/JCI67228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung J., Esposito M.T., Gandillet A., Zeisig B.B., Griessinger E., Bonnet D., and So C.W.. 2010. β-Catenin mediates the establishment and drug resistance of MLL leukemic stem cells. Cancer Cell. 18:606–618. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W.M., Liu X., Shen J., Jovanovic O., Pohl E.E., Gerson S.L., Finkel T., Broxmeyer H.E., and Qu C.K.. 2013. Metabolic regulation by the mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1 is required for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 12:62–74. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Mackenzie E.D., Karim S.A., Hedley A., Blyth K., Kalna G., Watson D.G., Szlosarek P., Frezza C., and Gottlieb E.. 2013. Reversed argininosuccinate lyase activity in fumarate hydratase-deficient cancer cells. Cancer Metab. 1:12 10.1186/2049-3002-1-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Cardaci S., Jerby L., MacKenzie E.D., Sciacovelli M., Johnson T.I., Gaude E., King A., Leach J.D., Edrada-Ebel R., et al. 2015. Fumarate induces redox-dependent senescence by modifying glutathione metabolism. Nat. Commun. 6:6001 10.1038/ncomms7001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber J., Radtke I., Pardee T.S., Zhao Z., Rappaport A.R., Luo W., McCurrach M.E., Yang M.M., Dolan M.E., Kogan S.C., et al. 2009. Mouse models of human AML accurately predict chemotherapy response. Genes Dev. 23:877–889. 10.1101/gad.1771409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]