Lyons et al. show that STAT3 negatively regulates TGF-β signaling via ERBIN and that cell-intrinsic deregulation of TGF-β pathway activation promotes the IL-4/IL-4Rα/GATA3 axis to support atopic phenotypes in humans.

Abstract

Nonimmunological connective tissue phenotypes in humans are common among some congenital and acquired allergic diseases. Several of these congenital disorders have been associated with either increased TGF-β activity or impaired STAT3 activation, suggesting that these pathways might intersect and that their disruption may contribute to atopy. In this study, we show that STAT3 negatively regulates TGF-β signaling via ERBB2-interacting protein (ERBIN), a SMAD anchor for receptor activation and SMAD2/3 binding protein. Individuals with dominant-negative STAT3 mutations (STAT3mut) or a loss-of-function mutation in ERBB2IP (ERBB2IPmut) have evidence of deregulated TGF-β signaling with increased regulatory T cells and total FOXP3 expression. These naturally occurring mutations, recapitulated in vitro, impair STAT3–ERBIN–SMAD2/3 complex formation and fail to constrain nuclear pSMAD2/3 in response to TGF-β. In turn, cell-intrinsic deregulation of TGF-β signaling is associated with increased functional IL-4Rα expression on naive lymphocytes and can induce expression and activation of the IL-4/IL-4Rα/GATA3 axis in vitro. These findings link increased TGF-β pathway activation in ERBB2IPmut and STAT3mut patient lymphocytes with increased T helper type 2 cytokine expression and elevated IgE.

Introduction

Several human syndromes present with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities providing genetic links between allergic findings—such as atopic dermatitis, elevated serum IgE, and eosinophilic esophagitis—and joint hypermobility, retained primary dentition, or vascular malformation (Holland et al., 2007; Morgan et al., 2007; Abonia et al., 2013; Frischmeyer-Guerrerio et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2016; Lyons et al., 2016). Enhanced cell-intrinsic TGF-β activity has been described in several connective tissue, hypermobility, and vascular phenotypes (Coucke et al., 2006; Loeys et al., 2006; Morissette et al., 2014), whereas dominant-negative STAT3 mutations have been shown to predispose individuals to similar joint and vascular abnormalities as part of the autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome (Freeman and Holland, 2009). However, whether these disorders are mechanistically linked and how altered STAT3 or TGF-β signaling may promote atopy remain unclear.

In vitro knockdown of STAT3 has been shown to potentiate TGF-β–mediated SMAD2/3 activation in human cancer lines (Luwor et al., 2013). Conversely, overexpression of the constitutively active STAT3 construct (STAT3C) was shown to have a negative effect on TGF-β signaling via SMAD3–STAT3 complex formation in HeCaT cells in vitro (Wang et al., 2016). This negative effect appeared to be dependent on the DNA-binding domain of STAT3, without which SMAD3 and STAT3 were unable to complex. Overexpression of this same construct in HeLa cells was also associated with up-regulation of ERBB2-interacting protein (ERBIN; Hu et al., 2013), a SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA) and SMAD-binding protein that negatively regulates TGF-β signaling through cytoplasmic sequestration of SMAD2/3 (Sflomos et al., 2011).

Results

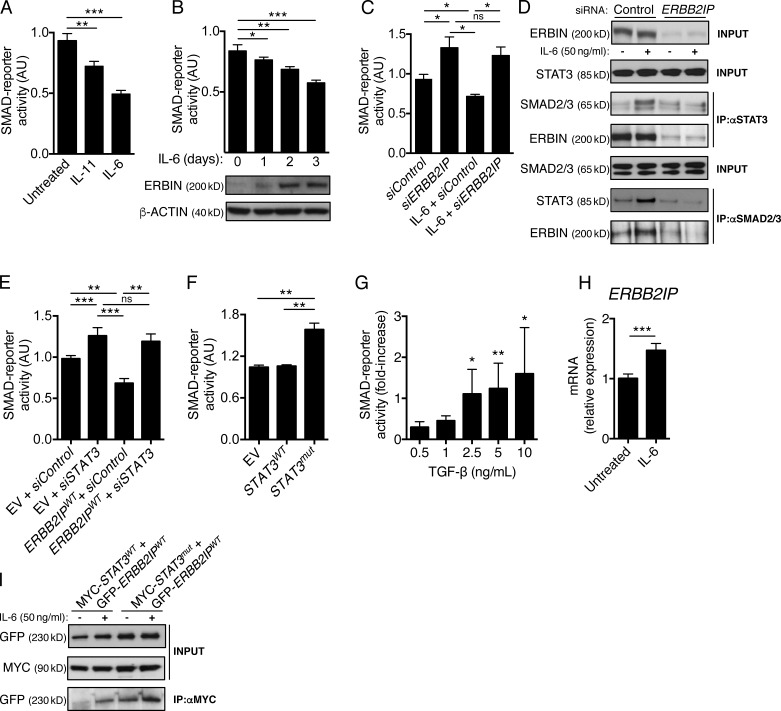

Using an established SMAD-reporter cell line (Oida and Weiner, 2011), we found that STAT3 activating cytokines IL-6 and IL-11 significantly suppressed TGF-β–mediated reporter activity in short-term cultures (Fig. 1 A). Suppression required IL-6 or IL-11 pretreatment, with a maximal effect occurring at 72 h suggesting a transcriptional effect, and correlated proportionally with induction of ERBIN protein expression induced by IL-6 (Fig. 1 B). ERBIN protein expression proved essential for IL-6–mediated pathway suppression, as the suppressive effects observed after pretreatment were completely abolished by ERBIN silencing (Fig. 1 C). ERBIN is known to form protein scaffolds and can complex with SMAD2/3, sequestering it in the cytoplasm, thus preventing transcriptional activity in a manner similar to that seen with STAT3C overexpression in vitro (Sflomos et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016). Using gel filtration chromatography, we identified a large molecular weight fraction containing SMAD2/3, STAT3, and ERBIN and that contained pSMAD2/3 after STAT3 activation by IL-6 (Fig. S1 A). By immunoprecipitation, we confirmed that, after STAT3 activation and associated induction of ERBIN, a complex containing SMAD2/3 and STAT3 can form and that ERBIN was required, as knockdown prevented this complex from forming (Fig. 1 D). Furthermore, we found that this complex containing STAT3 was necessary for the suppressive effects of ERBIN, as STAT3 knockdown abolished the reduction in TGF-β pathway activation seen after ERBIN overexpression (Fig. 1 E).

Figure 1.

STAT3 negatively regulates TGF-β pathway activation via ERBIN. (A) TGF-β–induced SMAD pathway activation in 293T SMAD-reporter line after short-term culture in the presence of STAT3-activating cytokine IL-6 or IL-11. (B) TGF-β–mediated pathway activation after stimulation in a SMAD-reporter cell line treated with IL-6 (top) and corresponding immunoblot of ERBIN expression from each culture (bottom). (C) TGF-β–induced SMAD-reporter activity after ERBIN knockdown (siERBB2IP) or transfection with scrambled siRNA (siControl) after 3-d culture in the presence or absence of IL-6. (D) Representative immunoblot of ERBIN, STAT3, and/or SMAD2/3 after immunoprecipitation (IP) of STAT3 or SMAD2/3 as indicated in 293T cells after siRNA-mediated knockdown of ERBIN in the presence or absence of STAT3 activation induced by treatment with IL-6. (E) TGF-β–induced SMAD-reporter activity after either STAT3 knockdown (siSTAT3) or scrambled siRNA transfection and cotransfection with either wild-type ERBIN (ERBB2IPWT) or empty vector (EV). (F) TGF-β–induced activation in SMAD-reporter line after transfection with empty vector, wild-type STAT3 (STAT3WT), or dominant-negative STAT3-mutant (STAT3mut) constructs. (G) TGF-β–induced SMAD-reporter activity after siRNA-mediated STAT3 silencing relative to activity after scrambled siRNA transfection. (H) ERBB2IP mRNA expression in purified control pan-T cells after treatment with 50 ng/ml IL-6. (I) Representative immunoblot of GFP after MYC immunoprecipitation in 293T cells in which MYC-tagged wild-type STAT3 (MYC-STAT3WT) or dominant-negative STAT3 (MYC-STAT3mut) constructs and GFP-tagged ERBIN wild-type (GFP-ERBB2IPWT) constructs were overexpressed in the presence or absence of STAT3 activation by IL-6. Data are representative or combined from at least three independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests and Wilcoxon matched pairs were used where appropriate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001. AU, arbitrary units.

To determine what effect dominant-negative STAT3 mutations found in humans might have on TGF-β signaling, we first overexpressed STAT3-mutant (STAT3mut) constructs in the SMAD-reporter cell line and found significant enhancement of responses to TGF-β (Fig. 1 F); similar deregulation of SMAD-reporter activity was seen after STAT3 knockdown (Fig. 1 G). Because mutant STAT3 protein is expressed in these STAT3mut individuals, we next sought to determine whether increased TGF-β activity in vitro resulted from impaired complex formation or reduced ERBIN expression. We confirmed that STAT3 activation by IL-6 was capable of inducing ERBB2IP expression in primary human T cells (Fig. 1 H; Hu et al., 2013). However, overexpression of mutant STAT3 (MYC-STAT3mut) with wild-type ERBIN (GFP-ERBB2IPWT) showed no impairment in complex formation relative to wild-type STAT3 (MYC-STAT3WT; Fig. 1 I), indicating that the increased TGF-β activity associated with STAT3mut transfection was not caused by altered complex formation. We confirmed significantly reduced ERBIN protein expression in primary dermal fibroblasts (from both SH2 and DNA-binding mutant individuals) as well as in CD4 cells from STAT3mut patients (Fig. 2, A and B).

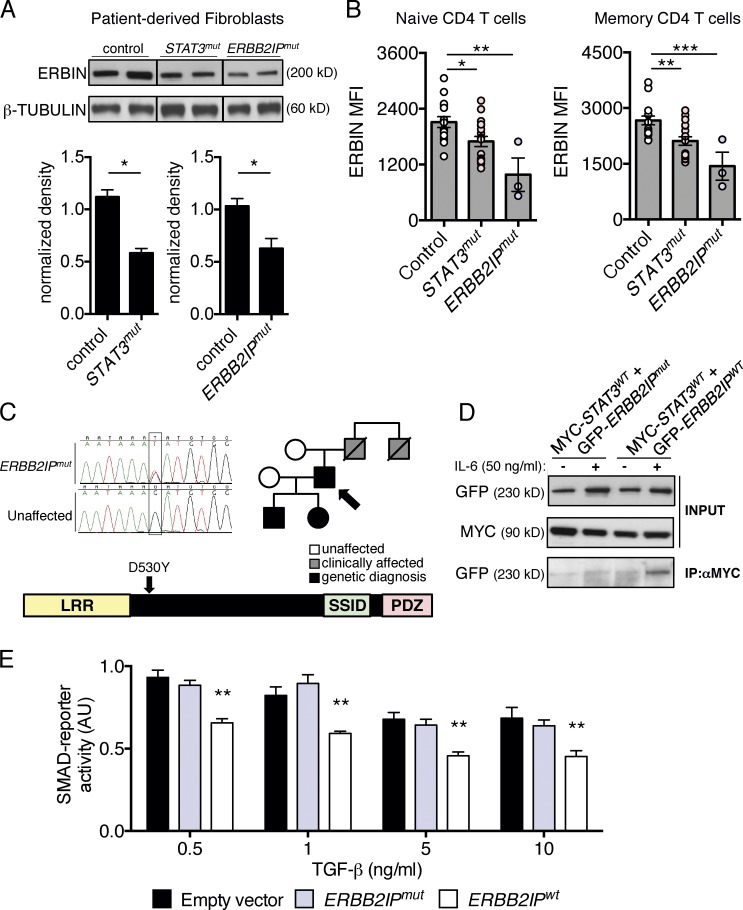

Figure 2.

ERBIN expression is reduced in STAT3mut patient cells and in newly identified individuals with an ERBB2IP mutation. (A, top) Representative immunoblot showing ERBIN expression in primary dermal fibroblasts from control, STAT3mut, and ERBB2IPmut patients. Lines indicate rearranged segments of one blot. (Bottom) Integrated densitometry of combined data comparing control (n = 4) with STAT3mut (SH2 mutants, n = 2; DNA-binding mutants, n = 2) or ERBB2IPmut (n = 2) individuals. (B) ERBIN expression in naive (CD45RO−) or memory (CD45RO+) CD4 T cells from control (n = 15), STAT3mut (n = 17), and ERBB2IPmut (n = 3) patients. (C) Pedigree, chromatogram, and schematic of mutation (c.1588G>T p.[D530Y]) in ERBB2IP identified in a family with a dominant congenital allergic disorder with connective tissue features. LRR, leucine rich repeat domain; PDZ, PSD95-Dlg1-zo-1–like domain; SSID, SMAD–SARA interacting domain. (D) Representative immunoblot of GFP after MYC immunoprecipitation (IP) in 293T cells in which MYC-tagged wild-type STAT3 (MYC-STAT3WT) and GFP-tagged ERBIN-mutant (GFP-ERBB2IPmut) or wild-type (GFP-ERBB2IPWT) constructs were overexpressed in the presence or absence of STAT3 activation by IL-6. (E) Effect of wild-type ERBIN (ERBB2IPWT) or mutant ERBIN (ERBB2IPmut) on TGF-β–induced SMAD-reporter activity. AU, arbitrary units. Data are representative or combined from at least three independent experiments and represented as the mean ± SEM. Paired and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests and Mann-Whitney tests were used where appropriate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001.

Subsequently, we identified a family with a dominantly inherited symptom complex that shared both allergic and nonimmunological connective tissue features with STAT3mut patients, including elevated IgE, eosinophilic esophagitis, joint hypermobility, and vascular abnormalities (Table 1 and Fig. 2 C; for phenotypic comparisons, see Table S1). Neither novel nor disease-causing variants were identified at STAT3, TNXB, COL3A1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, TGFB2, or TGFB3. Exome sequencing did identify a rare disease-segregating variant (c.1588G>T p.[D530Y]) in ERBB2IP (allelic frequency 0.000076 in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database; not present in 1000 Genomes database), the gene encoding ERBIN (Fig. 2 C). This variant was predicted to be pathogenic and was associated with significantly reduced ERBIN protein expression in primary dermal fibroblasts and CD4 cells (ERBB2IPmut; Fig. 2, A and B). The index patient’s father had succumbed to an acute cardiac event related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy at age 28 yr, a phenotype seen in ERBB2IP knockout mice (Rachmin et al., 2014). In addition to reduced ERBIN protein expression, the variant also impaired ERBIN–STAT3 complex formation, as the mutant construct (GFP-ERBB2IPmut) failed to coimmunoprecipitate with STAT3WT after overexpression (Fig. 2 D). Although the mutant failed to suppress TGF-β signaling in the SMAD-reporter line, a dominant-negative effect on endogenous ERBIN was not observed, as no enhancement in SMAD-reporter activity was seen after ERBB2IPmut overexpression (Fig. 2 E).

Table 1. Immunological findings among ERBB2IPmut individuals.

| Cell counts | Serum Ig | Antibody titers | Lymphocyte subsets | Serum tryptase | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ | CD8+ | CD20+ | |||||||||||||||||||

| ALC | ANC | AEC | IgG | IgA | IgM | IgE | Tetanus | Pneumococcus | Total | Memorya | Total | Memorya | Total | Memoryb | |||||||

| cells/µL | cells/µL | cells/µL | mg/dL | mg/dL | mg/dL | IU/ml | IU/ml | >1.3 µg/ml | cells/µl | % | cells/µl | % | cells/µl | % | ng/ml | ||||||

| Ref. | 1,320– 3,570 | 1,780– 5,380 | 40–540 | 700– 1,600 | 91–499 | 34–342 | 0–90 | >0.15 | 16/23 | 359– 1,565 | 13–50 | 178–853 | 3–16 | 59–329 | 0.8–3.6 | <11.4 | |||||

| 14-y M | 3,290– 4,550c | 1,430– 2,410 | 520– 2,880 | 368– 898 | 16–51 | 45–115 | 333–898 | 2.21 | 21/23 | 1,670 | 7.2 | 952 | 2 | 438 | 1.5 | 5.3 | |||||

| 11-y F | 4,450– 7,720c | 1,410– 1,860 | 90–680 | 693–737 | 68–89 | 90–102 | 10–98 | 0.35 | 20/23 | 2,506 | 9 | 1,501 | 5.1 | 794 | 3.4 | 4.2 | |||||

| 43-y M | 2,060–3,010 | 1,810–4,290 | 80–310 | 946–1,290 | 137–194 | 55–82 | 20–200 | 1.62 | 13/23 | 1,457 | 20 | 461 | 5.5 | 381 | 1.7 | 5.2 | |||||

Abbreviations used: AEC, absolute eosinophil count; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; F, female; M, male; Ref., reference range; y, year old.

T cell memory was defined as CD45RO+.

B cell memory was defined as CD27+.

Increased total lymphocyte counts and reduced memory populations relative to adult reference values are a result of the young age of these individuals and do not represent defective memory formation or other pathology.

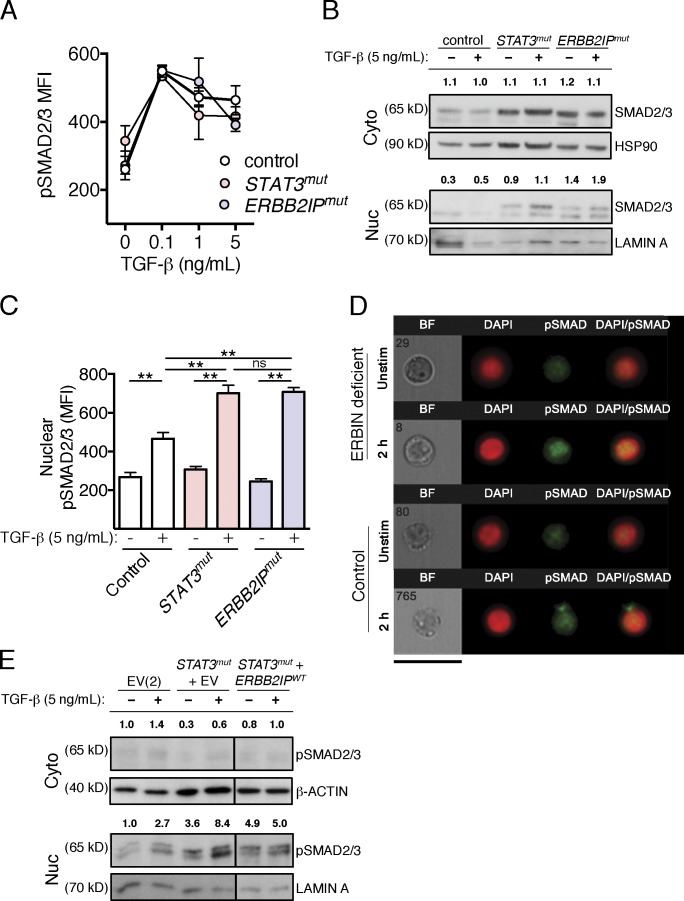

Reduced ERBIN expression in both STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patient cells and impaired STAT3–ERBIN complex formation in ERBB2IPmut patient cells did not affect total cellular pSMAD2/3 levels in response to TGF-β (Fig. 3 A) but was associated with increased nuclear SMAD2/3 levels in primary T cells (Fig. 3 B) and increased nuclear pSMAD2/3 in lymphocytes (Fig. 3, C and D), consistent with the role of ERBIN in sequestering cytoplasmic SMAD2/3. The same effect could be observed after overexpression of STAT3mut in 293T cells, which resulted in enhanced nuclear pSMAD2/3 that could be partially normalized by cotransfection with ERBB2IPWT (Fig. 3 E).

Figure 3.

TGF-β–induced nuclear SMAD2/3 is increased in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut lymphocytes. (A) Total pSMAD2/3 MFI shown as mean ± SEM in control (n = 4), STAT3mut (n = 2), or ERBB2IPmut (n = 2) CD4 lymphocytes after 2-h stimulation with TGF-β. (B) Representative immunoblot of nuclear (Nuc; bottom) and cytoplasmic (Cyto; top) SMAD2/3 in ERBB2IPmut and STAT3mut patient PBMCs compared with controls after TGF-β stimulation. Integrated densitometry normalized to lamin A or HSP90 is provided above each condition. (C and D) Representative quantification (C) and images (D) from Amnis ImageStream analysis (>1200 cells per condition) of nuclear pSMAD2/3 with and without TGF-β stimulation in control, STAT3mut, and ERBB2IPmut patient lymphocytes using a DAPI nuclear mask, shown as geometric mean ± 95% confidence interval. BF, brightfield; Unstim, unstimulated. Bar, 40 µm. (E) Representative immunoblot of nuclear (bottom) and cytoplasmic (top) pSMAD2/3 after cotransfection with a dominant-negative STAT3 (STAT3mut) construct and empty vector (EV), wild-type ERBIN (ERBB2IPWT), or with only the two corresponding empty vectors (EV[2]). Integrated densitometry normalized to lamin A or β-actin is provided above each condition. Data are representative or combined from at least two independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests and Mann-Whitney tests were used where appropriate. **, P < 0.005.

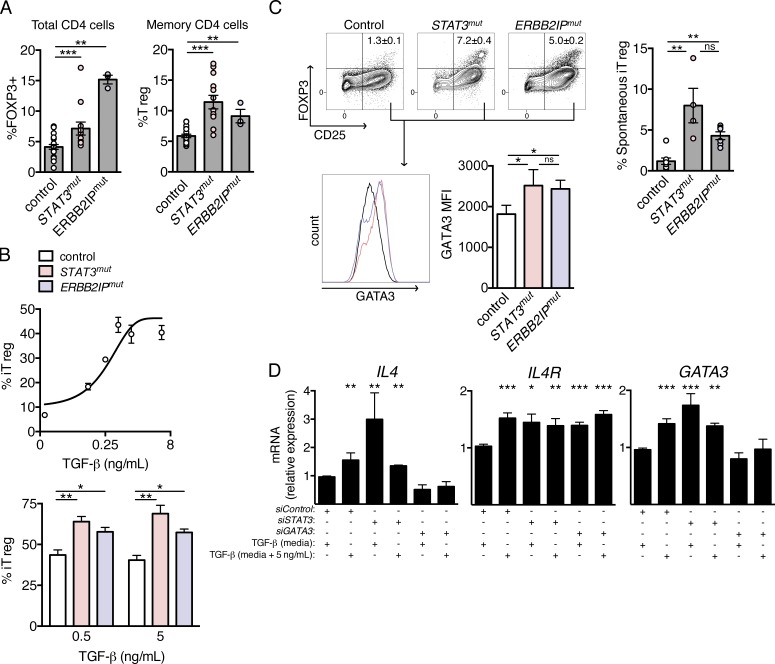

TGF-β is critical for FOXP3 expression after CD4 cell activation and is likely essential for regulatory T cell (T reg cell) ontogeny (Tran et al., 2007; Ouyang et al., 2010). To determine the potential in vivo consequences of reduced ERBIN expression and associated TGF-β pathway deregulation in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients, we began by examining these outcomes in primary cells. 4-h T cell stimulation ex vivo resulted in significantly higher FOXP3 expression among STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patient total CD4 lymphocytes compared with controls (Fig. 4 A, left). This agreed with increased T reg cells ex vivo (defined as CD4+FOXP3+CD25brightCD127low) among STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patient CD4 memory (CD45RO+) cells compared with controls (Fig. 4 A, right). In addition, to increased circulating T reg cells, naive CD4 T cells from STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients more readily differentiated into inducible T reg cells (iT reg cells) in vitro (Fig. 4 B, bottom), an effect that was found to be dose dependent on TGF-β in control naive CD4 cells (Fig. 4 B, top) but independent of IL-2 concentration in our system, in controls as well as STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut cells (Fig. S2, A and B). Furthermore, no difference in IL-2–induced STAT5 phosphorylation within STAT3mut patient T cells (Fig. S2 C) or in IL-6–mediated STAT3 phosphorylation within ERBB2IPmut patient T cells (Fig. S2 D) was found when compared with controls.

Figure 4.

Increased TGF-β sensitivity in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut CD4 lymphocytes is associated with increased T reg cells and induced GATA3 expression in vitro. (A, left) FOXP3 induction in total CD4+ T cells after short-term stimulation of control (n = 20), dominant-negative STAT3-mutant (STAT3mut; n = 13), and ERBIN-mutant (ERBB2IPmut; n = 3) individual cells. (Right) Prevalence of regulatory T cells (T reg) among memory (CD45RO+) cells from control (n = 20), STAT3mut (n = 12), and ERBB2IPmut (n = 3) patients. (B, top) Dose response of inducible regulatory T cells (iT reg) to TGF-β concentration in control naive CD4 lymphocytes in vitro. (Bottom) Percent iT reg cells obtained in cultures of control, STAT3mut, and ERBB2IPmut patient lymphocytes at the indicated concentrations of TGF-β. (C, top) Contour plot of FOXP3 and CD25 expression showing the spontaneous iT reg cell (FOXP3+CD25bright) population obtained after culture of naive CD4 lymphocytes with weak (0.5 µg/ml αCD3) TCR stimulation under nonskewing conditions, in the presence of IL-2. (Right) Combined data. (Bottom) Representative histograms of GATA3 expression among FOXP3−CD25+ cells from these same cultures (left) and combined data (right). (D) Relative quantitation of IL4, IL4R, and GATA3 genes in Jurkat T cells after knockdown of STAT3 (siSTAT3), GATA3 (siGATA3), or scrambled control (siControl) under standard culture conditions (10% FCS, determined to contain 10% of maximal TGF-β activity [media]) or in the presence of exogenous TGF-β (media + 5 ng/ml). Data are representative or combined from at least three independent experiments and are represented as the mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests and Mann-Whitney tests were used where appropriate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001.

The STAT3 DNA-binding domain was previously reported as necessary for STAT3–SMAD3 complex formation and negative regulation of TGF-β activation (Luwor et al., 2013). However, neither the observed increase in FOXP3 expression nor the increase in T reg cell number was dependent on the location of dominant-negative STAT3 mutations (SH2 or DNA-binding domains; Fig. S2 E). Therefore, deleting the DNA-binding domain of STAT3C may have prevented ERBIN transcription and secondarily reduced complex formation rather than eliminating the requirement of that domain for ERBIN interaction.

During T cell activation, weak TCR signaling has been associated with development of both T helper type 2 cells (Th2 cells) and iT reg cells (Turner et al., 2009; Milner et al., 2010; van Panhuys et al., 2014). Although several mechanisms have been shown to contribute to Th2 cell skewing in this context, TGF-β pathway activation might directly contribute to both. In addition to promoting FOXP3 expression, TGF-β–dependent SMAD3 activation has been shown to potentiate the transcriptional activity of GATA3, the canonical Th2 transcription factor, through direct complex formation (Blokzijl et al., 2002). TGF-β has also been shown to induce IL-4Rα in a SMAD3-dependent manner in a mouse model (Chen et al., 2015). Furthermore, dysregulated expression of GATA3 and GATA3 targets has been reported in syndromic and nonsyndromic allergy (Frischmeyer-Guerrerio et al., 2013; Noval Rivas et al., 2015). To determine whether deregulated TGF-β signaling might contribute to either fate, naive CD4+ T cells were subjected to weak TCR-mediated activation with low-dose anti-CD3, co-stimulated with anti-CD28, and cultured under nonskewing conditions in the presence of IL-2 without exogenous TGF-β. Increased spontaneous iT reg cells were observed in both STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patient cultures compared with controls (Fig. 4 C, top), which could be recapitulated in control naive CD4 cells after siRNA-mediated knockdown of STAT3 or ERBB2IP (Fig. S2 E), and were associated with a significant increase in GATA3 expression from activated (CD25+) FOXP3− cells in these same cultures (Fig. 4 C, bottom). Ex vivo, corresponding increases in T reg cells and total FOXP3 expression (Fig. 3 A) also did not appear dependent on the location of STAT3 mutations (Fig. S2 F).

Expression of both GATA3 and IL-4 is canonically associated with lineage-committed effector Th2 cell populations. However, GATA3 can drive a multitude of functions beyond CD4 effector function, including but not limited to tissue ILC2s, which could further mucosal allergic responses (Tindemans et al., 2014). In T reg cells, GATA3 expression appears to both limit FOXP3 and promote tolerance at some stages of expression in mice (Wang et al., 2011; Wohlfert et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2015), whereas in humans, coexpression may be pathogenic and has been associated with allergic disease (Frischmeyer-Guerrerio et al., 2013; Noval Rivas et al., 2015; Lexmond et al., 2016). Because manipulation of primary cells and expression of these targets may be subject to disease state (e.g., atopic dermatitis flare), we began by examining the effects of TGF-β on the IL-4/IL-4Rα/GATA3 axis in Jurkat T cells. Both exogenous TGF-β treatment and STAT3 knockdown significantly induced IL4, IL4R, and GATA3 transcript levels (Fig. 4 D and Fig. S3 A), whereas TBX21 (encoding T-BET, the canonical Th1 transcription factor) levels were unaffected by TGF-β treatment (Fig. S3 B). Transcription of IL-4 appeared to be co-dependent on GATA3, as GATA3 knockdown significantly reduced responsiveness to TGF-β (Fig. 4 D); however, consistent with the previous study in mice, IL4R induction by TGF-β appeared to have no such dependence on GATA3 coexpression (Chen et al., 2015).

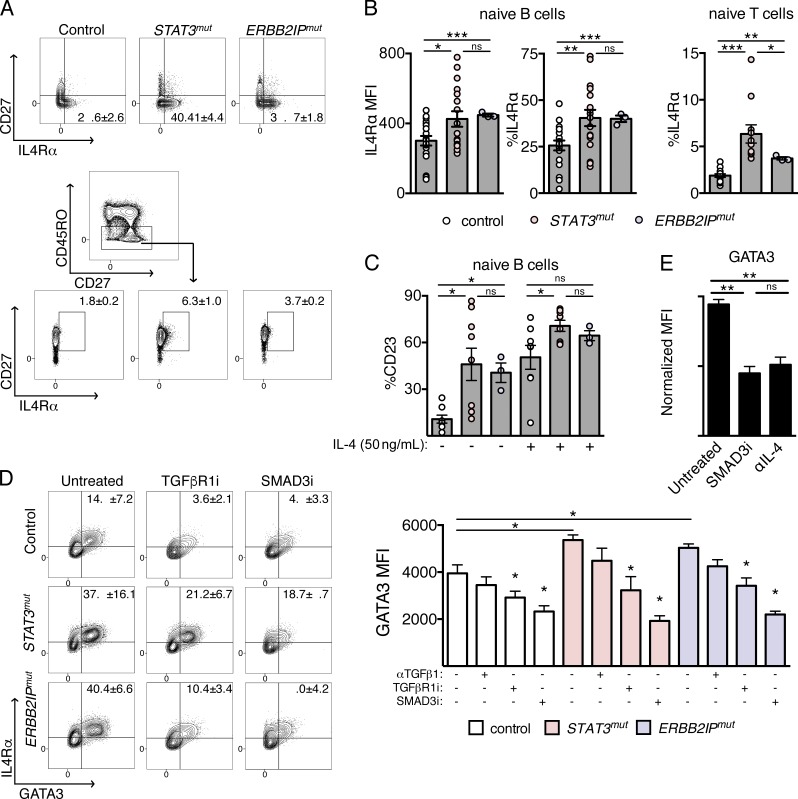

To investigate whether an atopic predisposition may exist in vivo, we focused our efforts on IL-4Rα expression. In mice, IL-4Rα expression on naive CD4 cells has been shown to directly and positively correlate with the number of Th2 effectors that are ultimately formed (Mikhalkevich et al., 2006). IL-4Rα–mediated STAT6 activation is also critical for class switch recombination to IgE (Geha et al., 2003). First, we determined that IL-4Rα surface expression in Jurkat T cells was responsive to TGF-β treatment and that this effect could be partially attenuated by pretreatment with IL-6 (Fig. S3 C). Examining naive lymphocytes ex vivo, we subsequently found that STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients had significantly greater IL-4Rα expression compared with controls (Fig. 5, A and B), and brightly IL-4Rα–positive (IL-4Rhi) cells had greater STAT6 phosphorylation in response to IL-4 (Fig. S3 D). We further found that the STAT6 B cell target CD23 was expressed at higher levels in CD19+ lymphocytes from STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients basally, as others have reported in STAT3mut patients (Deenick et al., 2013). After IL-4 stimulation, a significantly greater induction of CD23 in STAT3mut naive B cells and both STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut memory B cells was also seen compared with controls (Fig. 5 C and Fig. S3 E).

Figure 5.

Increased functional IL-4Rα expression in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut naive lymphocytes promotes TGF-β–dependent GATA3 expression in CD4 T cells. (A) Contour plots demonstrating expression of IL-4Rα ex vivo on naive (CD27−) B cells (top) and contour plots showing CD27 and IL-4Rα coexpression and gating strategy of naive (CD45RO−) T cells (bottom) from control, STAT3mut, and ERBB2IPmut patients. (B) Combined ex vivo IL-4Rα expression on naive lymphocytes from control (n = 19), STAT3mut (n = 17), and ERBB2IPmut (n = 3) individuals. MFI on naive (CD27−) B cells (left) and percentage of naive (CD27−) B cells (middle) and of CD27+ naive (CD45RO−) CD4 cells (right) expressing IL-4Rα are shown. (C) Percentage of naive (CD27−) B cells from controls (n = 8), STAT3mut (n = 8), and ERBB2IPmut (n = 3) individuals expressing the STAT6-target CD23 ex vivo or after short-term stimulation with IL-4 as indicated. (D) IL-4Rα and resulting GATA3 expression in control, STAT3mut, and ERBB2IPmut naive CD4 T cells after activation (CD69+) with weak TCR stimulation under nonskewing conditions in the presence or absence of a TGF-β1–neutralizing antibody (αTGFβ1), a TGFβR1 inhibitor (TGFβR1i), or a selective SMAD3 inhibitor (SMAD3i). Contour plots (left) and combined GATA3 MFI (right) are shown. (E) Comparison of GATA3 expression in activated (CD69+) control naive CD4 cells, as normalized MFI, cultured with 10 µg/ml neutralizing IL-4 antibody (αIL-4) or SMAD3i under the same conditions as in D. Data are representative or combined from at least three independent experiments and are represented as the mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests and Mann-Whitney tests were used where appropriate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001.

TCR-mediated activation of CD4 lymphocytes has been shown to enhance IL-4Rα expression independently of IL-4 expression (Liao et al., 2008); however, exogenous TGF-β alters naive CD4 proliferation and homeostasis (McKarns and Schwartz, 2005). Many compensatory mechanisms exist to tightly regulate and limit the immunological effects of exogenous TGF-β pathway activation (Engel et al., 1998; Miyazono, 2000; Wrana, 2000), and the absence of reported allergic phenotypes among Marfan syndrome patients (caused by FBN1 mutations) and arterial tortuosity syndrome patients (caused by SLC2A10 mutations) provides clinical evidence to suggest that cell-intrinsic defects in TGF-β pathway activation are critical to atopic predisposition in this context (Dietz et al., 1991; Coucke et al., 2006). To circumvent this problem and determine the effect that intrinsic deregulation of TGF-β pathway signaling may have on IL-4Rα expression, we again cultured naive CD4 lymphocytes with weak TCR stimulation, but, this time, in the presence or absence of selective TGF-β pathway inhibition or a neutralizing TGF-β antibody (αTGFβ1), and looked for an effect on IL-4Rα expression and associated GATA3 induction. After short-term culture of naive CD4 cells under nonskewing conditions, elevated IL-4Rα expression and, more importantly, GATA3 induction in CD69+ activated cells were greater in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients compared with controls (Fig. 5 D, and Fig. S4, A and B). Selective SMAD3 inhibition (SMAD3i) had the greatest effect on normalizing GATA3 expression in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patient lymphocytes, an effect comparable with IL-4 neutralization (Fig. 5 E), rendering levels below that of untreated controls, whereas the TGFβR1 inhibitor (TGFβR1i) had a modest effect, and αTGFβ1 resulted in only a nonsignificant reduction. Control naive CD4 cells also showed significant reductions in IL-4Rα and associated GATA3 expression after SMAD3i and TGFβR1i treatment (Fig. 5 D and Fig. S4 B).

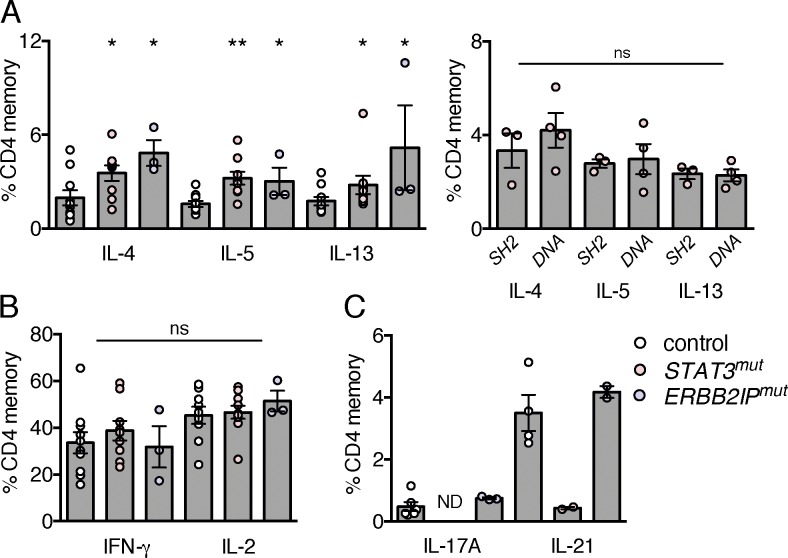

These findings were associated with increased ex vivo expression of the GATA3-dependent Th2 cytokines, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 among STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients (Fig. 6 A). Again, this appeared to be independent of the mutated STAT3 domain and, importantly, occurred in isolation from any disruption in Th1 cytokine production (Fig. 6 B) and in ERBB2IPmut patients was not accompanied by other CD4 defects known to occur in STAT3mut patients within Th17 and T follicular helper cell compartments caused by defective STAT3 signaling (Fig. 6 C). Clinically, these findings manifest as shared allergic and connective tissue phenotypes. However, mucosal susceptibility to candida, impairment in T cell and B cell memory, and class switching appear unique to STAT3mut individuals. One ERBB2IPmut individual has recently developed clinically asymptomatic hypogammaglobulinemia but has protective antibody responses (Table 1 and Table S1).

Figure 6.

Increased Th2 cytokine production in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut individual CD4 lymphocytes ex vivo. (A) Ex vivo cytokine expression in control (n = 10), ERBB2IPmut (n = 3), and STAT3mut memory (n = 9; CD45RO+) CD4 T cells. (B) Th2 cytokine expression of STAT3-mutant patients (STAT3mut) with SH2-domain mutations (n = 3) or DNA-binding–domain mutations (n = 4). (C) Ex vivo IL-17 expression in control (n = 6) and ERBB2IPmut (n = 3) and IL-21 expression in control (n = 4), ERBB2IPmut (n = 2), and STAT3mut memory (n = 2; CD45RO+) CD4 T cells. Data are combined from at least two independent experiments and are represented as the mean ± SEM. Mann-Whitney tests were used. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

Discussion

These results suggest that STAT3 activation promotes ERBIN expression and negatively regulates TGF-β activity by the formation of a STAT3–ERBIN–SMAD2/3 complex, thereby sequestering SMAD2/3 in the cytoplasm. Impaired basal STAT3 signaling reduces ERBIN expression and deregulates TGF-β pathway activation, leading to increased circulating T reg cells and functional IL-4Rα expression on naive lymphocytes in humans. TGF-β can drive IL-4/IL-4R/GATA3 expression in vitro, and enhanced TGF-β–induced SMAD2/3 activity correlates with increased Th2 cytokine–expressing memory cells and elevated serum IgE in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut patients. These findings may help explain why these syndromes share allergic and nonimmunological phenotypes. Moreover, the IL-4Rα/GATA3 axis can be restrained in vitro with SMAD3 inhibition in this context, suggesting a novel pathway for treatment of these disorders and potentially for atopic diatheses associated with STAT3 or TGF-β pathway disruptions more generally. Furthermore, IL-4Rα blockade, used successfully in a variety of atopic disorders (Wenzel et al., 2013; Beck et al., 2014; Bachert et al., 2016; Thaçi et al., 2016), may be more effective in patients with evidence of disrupted STAT3 or enhanced TGF-β signaling.

Materials and methods

Human subjects

All ERBB2IPmut patients and family members provided informed consent on National Institutes of Health (NIH) institutional review board–approved research protocols designed to study atopy (NCT01164241) and hyper-IgE syndromes (NCT00006150). Comprehensive histories, review of all available outside records, serial clinical evaluations, and therapeutic interventions were all performed at the Clinical Center of NIH. All clinical immunological laboratory tests were performed by the Department of Laboratory Medicine at NIH. STAT3mut patients were actively enrolled on a natural history protocol and followed at NIH having provided informed consent for the study (NCT00006150).

Genetic sequencing

Exome sequencing and data analysis were performed as previously described to identify ERBB2IPmut patients (Zhang et al., 2014). Novel candidate variants were filtered by 1000 Genomes, dbSNP, and Exome Aggregation Consortium databases, as well as by an in-house database with over 500 exomes. Candidate variants were identified based on an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. Segregating mutations identified by whole-exome sequencing were verified by Sanger sequencing of the candidate gene as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). Before study initiation, STAT3mut patients had been identified clinically and confirmed genetically by Sanger sequencing to have dominant-negative STAT3 mutations as previously described (Holland et al., 2007).

Antibodies, siRNAs, and expression plasmids

For flow cytometric analyses, the following antibodies were used: anti-CD3 AF700/APC, anti-CD4 BUV395/FITC/APC-H7, anti-CD19 APC/BV605, anti-CD25 PE-Cy7/APC-H7, anti-CD27 v450, anti-CD69 FITC, anti-CD127 AF647, anti-GATA3 AF488/AF647, anti–IFN-γ v450, anti–IL-2 FITC, anti–IL-4 PE-Cy7, anti–IL-5 PE, anti–IL-13 BV711, anti-pSMAD2/3 PE/AF647, anti-pSTAT3 (Y705) AF647, anti-pSTAT5 (Y694) Pacific blue, and anti-pSTAT6 (Y641) APC (BD); anti-FOXP3 efluor450, anti–IL-17A APC, anti–IL-21 efluor660, and anti-CD23 PE-Cy7/FITC (eBioscience); anti-CD45RO Texas Red PE (Beckman Coulter); and anti-CD124 (IL-4Rα) PE (BioLegend). LIVE/DEAD Fixable blue and aqua stains (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for flow cytometry, and DAPI was used for Amnis ImageStream flow cytometry.

The following were used for immunoblotting: anti–β-actin, anti–β-tubulin, anti-HSP90, anti–IL-4Rα, anti–lamin A/C, anti-pSMAD2/3, anti-SMAD2/3, and anti-STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology); anti-ERBB2IP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; Proteintech); and anti–turbo GFP (OriGene). Appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for immunoblotting (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). For immunoprecipitation, anti-STAT3, anti-SMAD2/3 monoclonal antibodies, or MYC sepharose and STAT3 sepharose (Cell Signaling Technology) were used.

Silencer select siRNAs directed against ERBB2IP and STAT3 and control siRNAs (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for knockdown experiments. The wild-type ERBIN (ERBB2IPWT) plasmid was generated by cloning the cDNA open reading frame (NCBI RefSeq accession no. NM_001253697.1) into the pCMV6-AC-GFP vector (OriGene). The ERBIN-mutant clone (ERBB2IPmut) was generated using site-directed mutagenesis introducing c.1588G>T p.(D530Y); both plasmids were confirmed by restriction digest on Southern blots and by Sanger sequencing (GenScript). Wild-type and dominant-negative STAT3-mutant (K658E and N647D; STAT3mut) and wild-type STAT3 (STAT3WT) Myk-DDK–tagged plasmids were provided by S.M. Holland.

PBMC preparation and stimulation

PBMCs were separated by Ficoll (Ficoll-Paque PLUS; GE Healthcare) gradient centrifugation. Naive CD4 T cells and pan-T cells were isolated by negative selection using magnetic-activated cell-sorting purification (Miltenyi Biotec) and used for transfections or cultures as indicated. STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 phosphorylation was detected after 25-min stimulation with 100 ng/ml IL-6, 40 U/ml IL-2 (PeproTech), or 50 ng/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems), respectively, as previously described (Milner et al., 2015). CD23 induction was measured after 16-h stimulation with 50 ng/ml IL-4. SMAD2/3 phosphorylation was assessed after TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml; R&D Systems) stimulation at the concentrations indicated for 2 h (unless otherwise shown).

Cell cultures

Primary dermal fibroblasts from ERBB2IPmut, STAT3mut, or healthy donors were grown in MEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 293T cells were cultured in IMDM with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine. Transfection of 293T cells with plasmids or siRNAs was accomplished with Nucleofector V (Lonza). Isolated naive primary CD4+ T cells were cultured in X-VIVO 15 media (Lonza). Plate-bound anti-CD3 (5 µg/ml unless otherwise indicated; eBioscience), soluble anti-CD28 (1 µg/ml; BD), and IL-2 (20 U/ml unless otherwise indicated; PeproTech) were used in nonskewing and iT reg cell conditions; TGF-β1 (R&D Systems) was used in iT reg cell cultures as indicated. When specified, a neutralizing anti-(α)TGFβ1 antibody (20 µg/ml; R&D Systems), a small molecule ALK5 inhibitor (TGFβR1i) GW788388, or a selective SMAD3 inhibitor (SMAD3i) SIS3 (Sigma-Aldrich) were added at 1 and 5 µM to nonskewing cultures of naive CD4 cells. To test specificity and inhibitory activity on TGF-β pathway activation, these inhibitors were added to the 293T SMAD-reporter line for 12 h before stimulation with TGF-β at the indicated concentrations.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

A total of 50 µg of protein was isolated as previously described (O’Connell et al., 2009), and nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were obtained as indicated using an NE-PER kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For immunoprecipitation, after the indicated transfection and/or stimulation, 293T cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (1× Mini protease inhibitor with EDTA [Roche], 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.75, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM PMSF protease inhibitor cocktail [Thermo Fisher Scientific]), precleared, and immunoprecipitated using Protein A/G Plus agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and monoclonal antibodies for SMAD2/3 or by using precoated sepharose beads for STAT3 and MYC (Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoblotting of whole cell lysates and immunoprecipitated proteins was performed using SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane as previously described (O’Connell et al., 2009). ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) was used to quantify integrated density.

Gel filtration chromatography

Prepacked Superdex 200 10/30 GL columns (GE Healthcare) were used on an AKTA Chromatographic system (GE Healthcare). 293T cells cultured in the presence or absence of 50 ng/ml IL-6 (PeproTech) were mechanically lysed using detergent-free buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1× protease inhibitors cocktail [Roche]). Samples were loaded onto the column (flow rate 0.5 ml/min; fraction 500 µl) and monitored by the eluent absorbance at 280 nm. High and medium molecular weight peaks (A1-15 and B15-14) were selected and subjected to Western blotting.

SMAD-reporter assay

293T cells stably expressing SMAD2/3 reporter construct (gift from A. Kitani, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) were stimulated with TGF-β1, and luciferase activity was measured as previously described (Oida and Weiner, 2011). In brief, the reporter line was pretreated with 50 ng/ml IL-6 or IL-11 (PeproTech) and/or transfected with constructs or siRNAs as indicated using Nucleofector kit V (Lonza), rested 12 h after transfection, and stimulated with 0.05–5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 16 h. Cells were washed, and GFP fluorescence was measured. Next, cells were passively lysed, and luciferase activity was quantified using ONE-Glo reagent (Promega) and normalized to GFP fluorescent intensity.

Real-time PCR

After treatment or transfection as indicated, mRNA was isolated from Jurkat T cells or from purified pan-T cells using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription was performed using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR reactions were performed using TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan gene expression assays probes for IL4, IL4R, GATA3, and TBX21 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 18S RNA served as the control target. The reactions were run on a 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and mRNA copy number was calculated by relative quantitation.

Flow cytometry and Amnis ImageStream

Ex vivo intracellular cytokine staining for IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-21, and IFN-γ after PMA and ionomycin stimulation was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). Ex vivo T reg cell staining was performed using anti-CD3, CD4, CD25, CD45RO, CD127, and FOXP3 antibodies as previously described (Milner et al., 2015). Induction of FOXP3 was assessed after PMA and ionomycin stimulation for 4 h. iT reg cell and nonskewing cultures were stained for CD4, CD25, FOXP3, and GATA3 or IL-4Rα where indicated. For iT reg cell and nonskewing cultures, a FOXP3/transcription factor–staining buffer set was used (eBioscience). Total pSMAD2/3 staining was performed using the FOXP3 buffer set according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Phospho-STAT staining was performed as previously described (using IL-2, -4, and -6; Milner et al., 2015). Ex vivo IL-4Rα expression and basal and IL-4–induced CD23 expression were obtained by staining live cells followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde. IL-4Rα levels in cultured naive CD4+ T cells were accomplished by surface costaining live CD4+ cells with CD25 and CD69 before fixation and permeabilization with the FOXP3 buffer set. All events were collected on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD) and analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star). For Amnis ImageStream nuclear pSMAD2/3 quantification, PBMCs were stained with CD4 and pSMAD2/3 as performed for flow cytometry, with the addition of DAPI to create a nuclear mask. Events were recorded and quantified using IDEAS software (EMD Millipore).

Statistical analysis

In flow cytometry plots, data are presented as geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the gated population. Unless otherwise indicated, remaining graphs represent the mean value ± SEM. Mann-Whitney, Wilcoxon matched pairs, and Student’s t tests were used to test significance of associations as indicated. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Prism (v6.05; GraphPad Software).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows primary gel filtration chromatography data. Fig. S2 shows increased T reg cells in ERBB2IPmut and STAT3mut patients are not associated with altered IL-2 responsiveness and are independent of the mutant STAT3 domain. Fig. S3 shows TGF-β can induce functionally active IL-4Rα expression in lymphocytes to promote STAT6-specific target expression. Fig. S4 shows greater IL-4Rα expression and increased GATA3 induction in STAT3mut and ERBB2IPmut naive CD4 lymphocytes are normalized by SMAD3 inhibition.

Acknowledgments

The investigators thank the patients, their families, and the healthy volunteers who contributed to this research, as well as the clinical staff of the Laboratory of Allergic Diseases and Laboratory of Clinical Infectious Diseases of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). We also thank Atsushi Kitani, Ph.D., for generously providing the SMAD-reporter cell line.

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research, and of the NIAID. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the NCI, NIH under contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: J.J. Lyons and J.D. Milner designed the study. A.F. Freeman, S.M. Holland, J.D. Milner, M.E. Rothenberg, J.J. Lyons, K.D. Stone, E. Mendoza-Caamal, L. Orozco, P.A. Frischmeyer-Guerrerio, C. Nelson, T. DiMaggio, N. Jones, and D.N. Darnell recruited patients and/or provided support for the protocols and study subjects. J.J. Lyons, A.F. Freeman, J.D. Milner, M.G. Lawrence, and A.M. Siegel collected and analyzed clinical data. J.J. Lyons, R.J. Hohman, and J.D. Milner oversaw and J.J. Lyons, Y. Liu, C.A. Ma, M.G. Lawrence, Y. Zhang, K. Karpe, M. Zhao, A.M. Siegel, and M.P. O’Connell designed and performed the functional studies. X. Yu, J.D. Hughes, J. McElwee, and J.D. Milner supported and/or performed genome sequencing and analysis of ERBB2IPmut individuals. J.J. Lyons and J.D. Milner prepared the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to discussion of the results and to manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- ERBIN

- ERBB2-interacting protein

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

References

- Abonia J.P., Wen T., Stucke E.M., Grotjan T., Griffith M.S., Kemme K.A., Collins M.H., Putnam P.E., Franciosi J.P., von Tiehl K.F., et al. . 2013. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132:378–386. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachert C., Mannent L., Naclerio R.M., Mullol J., Ferguson B.J., Gevaert P., Hellings P., Jiao L., Wang L., Evans R.R., et al. . 2016. Effect of subcutaneous dupilumab on nasal polyp burden in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 315:469–479. 10.1001/jama.2015.19330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck L.A., Thaçi D., Hamilton J.D., Graham N.M., Bieber T., Rocklin R., Ming J.E., Ren H., Kao R., Simpson E., et al. . 2014. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 371:130–139. 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokzijl A., ten Dijke P., and Ibáñez C.F.. 2002. Physical and functional interaction between GATA-3 and Smad3 allows TGF-β regulation of GATA target genes. Curr. Biol. 12:35–45. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00623-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Akiyama K., Wang D., Xu X., Li B., Moshaverinia A., Brombacher F., Sun L., and Shi S.. 2015. mTOR inhibition rescues osteopenia in mice with systemic sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 212:73–91. 10.1084/jem.20140643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coucke P.J., Willaert A., Wessels M.W., Callewaert B., Zoppi N., De Backer J., Fox J.E., Mancini G.M., Kambouris M., Gardella R., et al. . 2006. Mutations in the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT10 alter angiogenesis and cause arterial tortuosity syndrome. Nat. Genet. 38:452–457. 10.1038/ng1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B.P., Epstein T., Kottyan L., Amin P., Martin L.J., Maddox A., Collins M.H., Sherrill J.D., Abonia J.P., and Rothenberg M.E.. 2016. Association of eosinophilic esophagitis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137:934–6.e5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deenick E.K., Avery D.T., Chan A., Berglund L.J., Ives M.L., Moens L., Stoddard J.L., Bustamante J., Boisson-Dupuis S., Tsumura M., et al. . 2013. Naive and memory human B cells have distinct requirements for STAT3 activation to differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells. J. Exp. Med. 210:2739–2753. 10.1084/jem.20130323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz H.C., Cutting G.R., Pyeritz R.E., Maslen C.L., Sakai L.Y., Corson G.M., Puffenberger E.G., Hamosh A., Nanthakumar E.J., Curristin S.M., et al. . 1991. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature. 352:337–339. 10.1038/352337a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel M.E., Datta P.K., and Moses H.L.. 1998. Signal transduction by transforming growth factor-β: a cooperative paradigm with extensive negative regulation. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 30-31:111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A.F., and Holland S.M.. 2009. Clinical manifestations, etiology, and pathogenesis of the hyper-IgE syndromes. Pediatr. Res. 65:32R–37R. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dc8c5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmeyer-Guerrerio P.A., Guerrerio A.L., Oswald G., Chichester K., Myers L., Halushka M.K., Oliva-Hemker M., Wood R.A., and Dietz H.C.. 2013. TGFβ receptor mutations impose a strong predisposition for human allergic disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:195ra94 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geha R.S., Jabara H.H., and Brodeur S.R.. 2003. The regulation of immunoglobulin E class-switch recombination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:721–732. 10.1038/nri1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S.M., DeLeo F.R., Elloumi H.Z., Hsu A.P., Uzel G., Brodsky N., Freeman A.F., Demidowich A., Davis J., Turner M.L., et al. . 2007. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:1608–1619. 10.1056/NEJMoa073687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Chen H., Duan C., Liu D., Qian L., Yang Z., Guo L., Song L., Yu M., Hu M., et al. . 2013. Deficiency of Erbin induces resistance of cervical cancer cells to anoikis in a STAT3-dependent manner. Oncogenesis. 2:e52 10.1038/oncsis.2013.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexmond W.S., Goettel J.A., Lyons J.J., Jacobse J., Deken M.M., Lawrence M.G., DiMaggio T.H., Kotlarz D., Garabedian E., Sackstein P., et al. . 2016. FOXP3+ Tregs require WASP to restrain Th2-mediated food allergy. J. Clin. Invest. 126:4030–4044. 10.1172/JCI85129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W., Schones D.E., Oh J., Cui Y., Cui K., Roh T.Y., Zhao K., and Leonard W.J.. 2008. Priming for T helper type 2 differentiation by interleukin 2–mediated induction of interleukin 4 receptor α-chain expression. Nat. Immunol. 9:1288–1296. 10.1038/ni.1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys B.L., Schwarze U., Holm T., Callewaert B.L., Thomas G.H., Pannu H., De Backer J.F., Oswald G.L., Symoens S., Manouvrier S., et al. . 2006. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-β receptor. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:788–798. 10.1056/NEJMoa055695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luwor R.B., Baradaran B., Taylor L.E., Iaria J., Nheu T.V., Amiry N., Hovens C.M., Wang B., Kaye A.H., and Zhu H.J.. 2013. Targeting Stat3 and Smad7 to restore TGF-β cytostatic regulation of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 32:2433–2441. 10.1038/onc.2012.260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J.J., Yu X., Hughes J.D., Le Q.T., Jamil A., Bai Y., Ho N., Zhao M., Liu Y., O’Connell M.P., et al. . 2016. Elevated basal serum tryptase identifies a multisystem disorder associated with increased TPSAB1 copy number. Nat. Genet. 48:1564–1569. 10.1038/ng.3696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKarns S.C., and Schwartz R.H.. 2005. Distinct effects of TGF-β1 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell survival, division, and IL-2 production: a role for T cell intrinsic Smad3. J. Immunol. 174:2071–2083. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhalkevich N., Becknell B., Caligiuri M.A., Bates M.D., Harvey R., and Zheng W.P.. 2006. Responsiveness of naive CD4 T cells to polarizing cytokine determines the ratio of Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 176:1553–1560. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner J.D., Fazilleau N., McHeyzer-Williams M., and Paul W.. 2010. Cutting edge: lack of high affinity competition for peptide in polyclonal CD4+ responses unmasks IL-4 production. J. Immunol. 184:6569–6573. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner J.D., Vogel T.P., Forbes L., Ma C.A., Stray-Pedersen A., Niemela J.E., Lyons J.J., Engelhardt K.R., Zhang Y., Topcagic N., et al. . 2015. Early-onset lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity caused by germline STAT3 gain-of-function mutations. Blood. 125:591–599. 10.1182/blood-2014-09-602763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K. 2000. Positive and negative regulation of TGF-beta signaling. J. Cell Sci. 113:1101–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A.W., Pearson S.B., Davies S., Gooi H.C., and Bird H.A.. 2007. Asthma and airways collapse in two heritable disorders of connective tissue. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66:1369–1373. 10.1136/ard.2006.062224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette R., Merke D.P., and McDonnell N.B.. 2014. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway abnormalities in tenascin-X deficiency associated with CAH-X syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 57:95–102. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noval Rivas M., Burton O.T., Wise P., Charbonnier L.M., Georgiev P., Oettgen H.C., Rachid R., and Chatila T.A.. 2015. Regulatory T cell reprogramming toward a Th2-cell-like lineage impairs oral tolerance and promotes food allergy. Immunity. 42:512–523. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell M.P., Fiori J.L., Kershner E.K., Frank B.P., Indig F.E., Taub D.D., Hoek K.S., and Weeraratna A.T.. 2009. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan modulation of Wnt5A signal transduction in metastatic melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284:28704–28712. 10.1074/jbc.M109.028498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oida T., and Weiner H.L.. 2011. Murine CD4 T cells produce a new form of TGF-β as measured by a newly developed TGF-β bioassay. PLoS One. 6:e18365 10.1371/journal.pone.0018365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang W., Beckett O., Ma Q., and Li M.O.. 2010. Transforming growth factor-β signaling curbs thymic negative selection promoting regulatory T cell development. Immunity. 32:642–653. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachmin I., Tshori S., Smith Y., Oppenheim A., Marchetto S., Kay G., Foo R.S., Dagan N., Golomb E., Gilon D., et al. . 2014. Erbin is a negative modulator of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:5902–5907. 10.1073/pnas.1320350111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sflomos G., Kostaras E., Panopoulou E., Pappas N., Kyrkou A., Politou A.S., Fotsis T., and Murphy C.. 2011. ERBIN is a new SARA-interacting protein: competition between SARA and SMAD2 and SMAD3 for binding to ERBIN. J. Cell Sci. 124:3209–3222. 10.1242/jcs.062307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaçi D., Simpson E.L., Beck L.A., Bieber T., Blauvelt A., Papp K., Soong W., Worm M., Szepietowski J.C., Sofen H., et al. . 2016. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 387:40–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00388-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindemans I., Serafini N., Di Santo J.P., and Hendriks R.W.. 2014. GATA-3 function in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity. 41:191–206. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran D.Q., Ramsey H., and Shevach E.M.. 2007. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3− T cells by T-cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor-β-dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood. 110:2983–2990. 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M.S., Kane L.P., and Morel P.A.. 2009. Dominant role of antigen dose in CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell induction and expansion. J. Immunol. 183:4895–4903. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Panhuys N., Klauschen F., and Germain R.N.. 2014. T-cell-receptor-dependent signal intensity dominantly controls CD4+ T cell polarization in vivo. Immunity. 41:63–74. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Yu Y., Sun C., Liu T., Liang T., Zhan L., Lin X., and Feng X.H.. 2016. STAT3 selectively interacts with Smad3 to antagonize TGF-β. Oncogene. 35:4388–4398. 10.1038/onc.2015.446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Su M.A., and Wan Y.Y.. 2011. An essential role of the transcription factor GATA-3 for the function of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 35:337–348. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel S., Ford L., Pearlman D., Spector S., Sher L., Skobieranda F., Wang L., Kirkesseli S., Rocklin R., Bock B., et al. . 2013. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:2455–2466. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfert E.A., Grainger J.R., Bouladoux N., Konkel J.E., Oldenhove G., Ribeiro C.H., Hall J.A., Yagi R., Naik S., Bhairavabhotla R., et al. . 2011. GATA3 controls Foxp3+ regulatory T cell fate during inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:4503–4515. 10.1172/JCI57456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrana J.L. 2000. Crossing Smads. Sci. STKE. 2000:re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Sharma S., Edwards J., Feigenbaum L., and Zhu J.. 2015. Dynamic expression of transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 by regulatory T cells maintains immunotolerance. Nat. Immunol. 16:197–206. 10.1038/ni.3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yu X., Ichikawa M., Lyons J.J., Datta S., Lamborn I.T., Jing H., Kim E.S., Biancalana M., Wolfe L.A., et al. . 2014. Autosomal recessive phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) mutations link glycosylation defects to atopy, immune deficiency, autoimmunity, and neurocognitive impairment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133:1400–1409.e5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]