Abstract

Depressive disorders often run in families, which, in addition to the genetic component, may point to the microbiome as a causative agent. Here, we employed a combination of behavioral, molecular and computational techniques to test the role of the microbiota in mediating despair behavior. In chronically stressed mice displaying despair behavior, we found that the microbiota composition and the metabolic signature dramatically change. Specifically, we observed reduced Lactobacillus and increased circulating kynurenine levels as the most prominent changes in stressed mice. Restoring intestinal Lactobacillus levels was sufficient to improve the metabolic alterations and behavioral abnormalities. Mechanistically, we identified that Lactobacillus-derived reactive oxygen species may suppress host kynurenine metabolism, by inhibiting the expression of the metabolizing enzyme, IDO1, in the intestine. Moreover, maintaining elevated kynurenine levels during Lactobacillus supplementation diminished the treatment benefits. Collectively, our data provide a mechanistic scenario for how a microbiota player (Lactobacillus) may contribute to regulating metabolism and resilience during stress.

Depression is one of the most common types of mental illnesses, affecting up to 7% of the population1,2. While improved diagnosis led to appreciation of the frequency of the disorder, better understanding of the mechanisms leading to depression is needed for the development of new therapeutic approaches for this debilitating disease. Based on both human and animal studies, several hypotheses have been proposed to underlie the etiology of depression, including monoamine deficiency, stress response dysregulation, neuronal plasticity deficits, and inflammation1,2,3. Genetic polymorphisms have also been linked to an increased risk for developing depression2. However, their prevalence cannot account for the frequency and familial nature of the disorder. Family history can also be viewed as having a “shared environment”, i.e. a shared microbiota composition. Therefore, we decided to explore the role of the gut microbiota in the development and maintenance of depressive behavior.

The microbiota, the collection of organisms inhabiting various organs, has been increasingly recognized to modulate host physiology4. Changes in gut microbiota composition have been linked to CNS function in animal models and human studies. In most studies, germ free mice show a decreased anxiety phenotype, but an exacerbated response to stress, and have numerous neurochemical disturbances5,6,7,8,9. Alteration of gut microbiota composition in despair and anxiety disorders has long been suspected from clinical observations, such as high co-morbidities of colitis and depression10,11,12.

In this study, we set out to understand whether and how microbiota alterations contribute to CNS dysfunction and behavioral abnormalities and whether the gut microbiota could be therapeutically targeted to alleviate depression. Here, we show that chronic stress significantly alters intestinal microbiota composition, primarily depleting the Lactobacillus compartment. ROS produced by Lactobacilli can inhibit kynurenine metabolism, a pathway that can negatively impact the brain when dysregulated. Surprisingly, therapeutic administration of L. reuteri to stressed mice improves metabolic homeostasis and corrects stress-induced despair behaviors.

Results

Microbiota composition is altered by unpredictable chronic mild stress

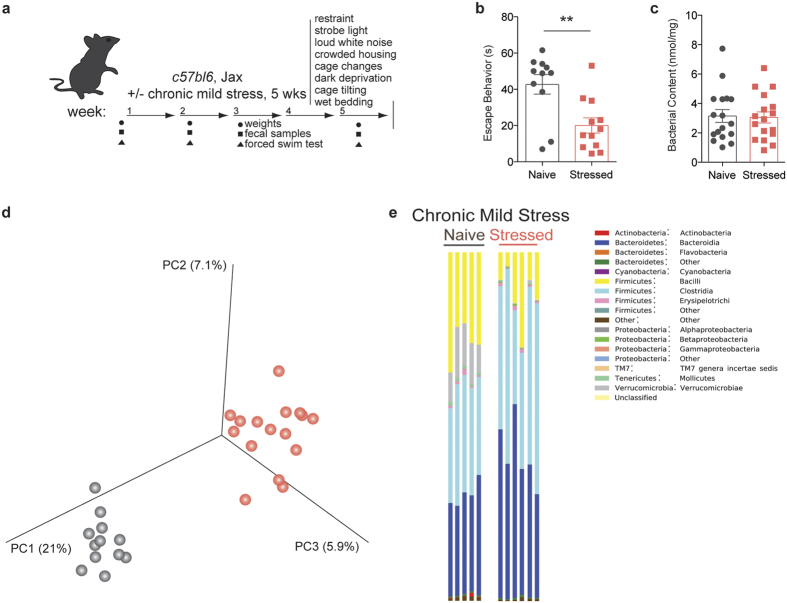

To determine whether chronic stress can directly affect the microbiota, we chose the unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) model to induce despair behavior13,14. Considering the dynamic nature of the intestinal microbiota, we posited that lasting changes must be observed over a prolonged period of time (e.g. weeks-months). The UCMS model seemed particularly appropriate due to the length and variety of the stress protocol (Fig. 1a). Consistent with previous reports, this protocol effectively induced despair behavior, as measured by the forced swim test (t(19) = 3.343, Welch’s correction applied, p = 0.0034; Fig. 1b)3,15,16. The assay measures the amount of time an animal struggles to escape an uncomfortable situation, a behavior typically affected in most models of depression and corrected by anti-depressant treatment. We verified that the forced swim test results were true despair behavior, as the animals show normal activity and locomotion in the open field test (Sup. Fig. 1a,b). The UCMS protocol did not significantly impact the weight and the food intake of stressed mice when compared to the control group (Sup. Fig. 1c,d).

Figure 1. Unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) induces despair behavior and microbiota dysregulation.

(a) Experimental design. (b) Quantification of escape behavior in the forced swim test (n = 11 naïve and 12 stressed; representative of 3 independent experiments; two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction, **p < 0.01; mean ± s.e.m.). (c) Total bacterial load quantification by qRT-PCR of 16S rRNA (n = 17 samples per group; two-tailed t-test; mean ± s.e.m.). (d) Principal coordinate analysis of microbiome communities in naïve and stressed mice. Analysis based on 2 UCMS experiments (n = 12 naïve and 16 stressed; representative of 2 sequencing experiments) (e) Representative graphs of bacterial class distribution in individual subjects show a decrease in bacilli (yellow) (n = 5 naïve and 6 stressed; representative of 2 sequencing experiments).

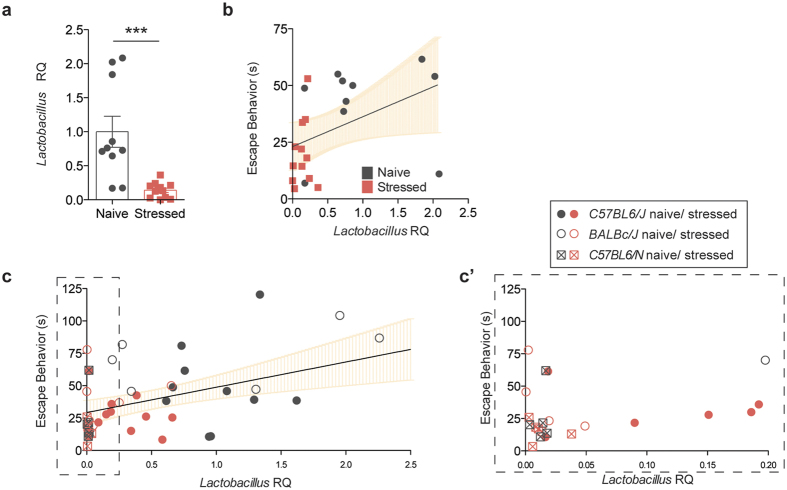

In order to assess the changes in microbiota composition that occur during chronic stress, we performed 16S rRNA sequencing on genomic DNA isolated from the fecal samples of naïve and stressed mice. The quantity of bacterial DNA in fecal pellets was not affected by stress, as demonstrated by 16S qPCR (t(33) = 0.4447, p = 6594; Fig. 1c). In terms of microbiota composition, principal coordinate analysis shows distinct clustering between samples from naïve and stressed mice, indicative of differences between the groups (Fig. 1d). A more in-depth taxonomic analysis of bacterial types revealed several changes in the microbiota composition (Fig. 1e shows one experimental cohort, Sup. Fig. 2 shows a different experimental cohort; bacterial classes are shown for ease of visualization). In our sequencing runs we observed between 14 and 29 significantly different genera between the naïve and stressed conditions. The variability in the starting microbiota (of naïve mice) and its changes (after stress) is not unexpected, as different shipments of mice, even from the same vendor, can have different microbiota compositions17,18. Overall, the most conserved microbiota change across all independent experiments was a decrease in bacillus class members in stressed mice (Fig. 1e, Sup. Fig. 2a). This class encompasses Lactobacillus and Turicibacter, and the decrease was also detectable at the genus level (Sup. Fig. 2b). Due to the abundance of literature linking Lactobacilli and behavior and the lack of studies and tools regarding Turicibacter species, we further focused on Lactobacillus as a confident potential player in the despair phenotype. We verified the net loss of Lactobacilli by qPCR (t(19) = 4.103, Welch’s correction applied, p = 0.0006; Fig. 2a) and selective fecal sample cultures using MRS agar supplemented with azide (t(9) = 2.993, Welch’s correction applied, p = 0.0157; Sup. Fig. 3a,b)19. These results demonstrate that chronic stress disturbs the microbiota homeostasis, in particular by decreasing the Lactobacillus levels. Correlation analysis returned a positive correlation (Spearman r = 0.5246, p = 0.0122) between the relative Lactobacillus load and the escape behavior displayed by a mouse (Fig. 2b). Our observation was not limited to C57BL/6J, as BALB/cJ and C57BL/6N mice also show significant correlation (Spearman r = 0.4682, p = 0.0012) between Lactobacillus levels and their escape behavior (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, C57BL/6N mice had very low starting levels of Lactobacillus, which corresponded to low escape behavior even in the absence of stress. Our data are in agreement with recent studies showing associations between lower Lactobacillus levels and stress20,21.

Figure 2. Lactobacillus levels correlate with depressive behavior.

(a) Lactobacillus quantification in fecal samples by qRT-PCR, relative to 16S rRNA (n = 10 naïve and 11 stressed; representative of 3 independent experiments; two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction, ***p < 0.001; mean ± s.e.m.). (b) Correlation analysis between Lactobacillus levels and escape behavior (n = 22 pairs, two-tailed Spearman r, **p = 0.01, line of best fit with 95% CI). (c) Correlation analysis between Lactobacillus levels and escape behavior in C57BL/6J (Jax), BALB/cJ (Jax), and C57BL/6N (Taconic), naive and stressed (n = 45 pairs, two-tailed Spearman r, **p = 0.01, line of best fit with 95% CI). (c’) Dashed insert with expanded X-axis for better resolution.

To gain insight into potential causes for changed microbiota composition, we further characterized intestinal physiology and immunity. Similarly to previous reports using stress models22,23, large intestinal transit time was significantly decreased in the stressed animals (t(19) = 4.275, Welch’s correction applied, p = 0.0004; Sup. Fig. 4a). Furthermore, we observed an increase in the total size and cellular content of the stressed small intestines (t(22) = 3.574, p = 0.0017; t(22) = 2.248, p = 0.0349; Sup. Fig. 4b,c). These changes in intestinal physiology in response to stress may underlie microbiota changes.

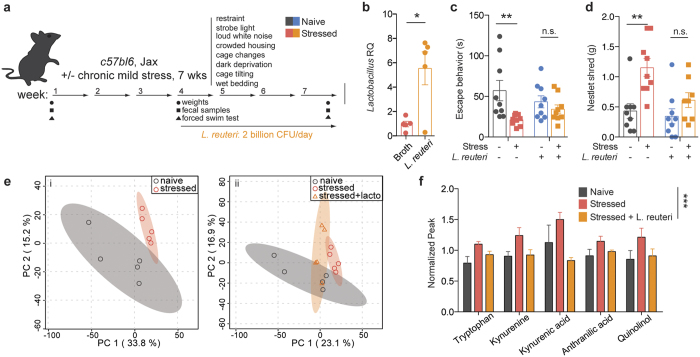

Treatment with a Lactobacillus species ameliorates despair behavior by restoring kynurenine metabolism

To assess whether Lactobacillus levels may play a role in mediating despair behaviors, we attempted to replenish the levels of the bacteria and then measure escape behavior. To this end, we subjected mice to the UCMS protocol for three weeks and then supplemented their diet with live cultures of L. reuteri, while continuing the stress protocol for additional 4 weeks (Fig. 3a). Lactobacillus reuteri (ATCC 23272) is a species that colonizes several vertebrate hosts, including rodents and humans, and was shown to improve despair and anxiety-like behaviors, including the forced swim test in mice24,25. This regimen indeed elevated Lactobacillus levels in the stressed mice (Fig. 3b, t(8) = 3.330, p = 0.0104). The increase in overall Lactobacillus was not due to a re-expansion of endogenous bacteria, but due to L. reuteri supplementation (Sup. Fig. 5). Moreover, in our experimental paradigm, L. reuteri supplementation ameliorated the despair behavior induced by UCMS (Fig. 3c, Fstress(1, 32) = 8.569, p = 0.0062; Finteraction(1, 32) = 3.005, p = 0.0926; Bonferroni post-hoc tbroth = 3.96, tL.reuteri = 0.8441). L. reuteri also improved the compulsive behavior observed in stressed mice, as measured by the nestlet shredding test (Fig. 3d, Fstress(1, 31) = 13.7, p = 0.0008; Ftreatment(1, 31) = 5.508, p = 0.0255; Bonferroni post-hoc tbroth = 3.861, tL.reuteri = 1.412). These data indicate that Lactobacillus levels may be mediating, at least in part, the depressive-like behavior.

Figure 3. Treatment with probiotic L. reuteri ameliorates the escape behavior induced by chronic stress.

(a) Experimental design of L. reuteri supplementation regimen. (b) qRT-PCR quantification of Lactobacillus levels in fecal samples of L. reuteri or broth-control treated mice, relative to 16S rRNA (n = 5; representative of 2 independent experiments; two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05; mean ± s.e.m.). (c) Forced swim test quantification of escape behavior of naïve and stressed mice treated with either L. reuteri or bacteria-free broth (n = 9 per group; representative of 2 independent experiments; 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc, **p < 0.01; mean ± s.e.m.). (d) Nestlet shredding test quantification of escape behavior of naïve and stressed mice treated with either L. reuteri or bacteria-free broth (n = 9 per group; representative of 2 independent experiments; 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc, **p < 0.01; mean ± s.e.m.). (e) Principal component analyses of serum metabolite composition after untargeted metabolomics assay (n = 5 mice per group) showing two (i) or three (ii) group comparisons; shaded areas represent 95% CI. (f) Normalized MS peaks of tryptophan - kynurenine pathway metabolites in the sera of naïve, stressed and L. reuteri treated stressed mice (n = 3–5 per group; 2-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001; mean ± s.e.m.).

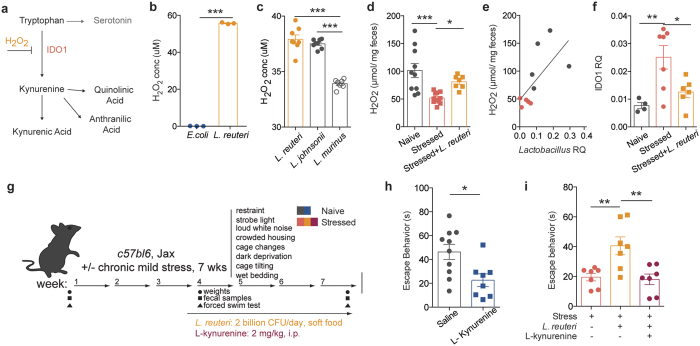

To get an insight into the potential mechanism of Lactobacillus-supported resiliency, we performed untargeted metabolomics analysis of serum samples to identify if and how metabolites composition was altered after chronic stress. Principal component analysis showed that the metabolic profile of stressed mice is clustered distinctly from that of naïve mice (Fig. 3ei). Treatment with L. reuteri modified the metabolic profile of stressed mice to an intermediate profile, suggesting that some of the stress associated metabolic alterations may be a consequence of decreased Lactobacillus levels, while others may be a direct effect of L. reuteri administration (Fig. 3eii). While several molecules were significantly different in our analysis (234 out of 4900 spectra), most returned spectra were not confidently matched to known molecules due to limitations in the metabolite library (Sup. Fig. 6). Of the identified compounds, we mined those increased in stressed animals and normalized by L. reuteri treatment. Among them, metabolites in the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway presented this pattern (Fig. 3f, F(2, 53) = 12.13, p < 0.0001). Evidence of dysregulation of this pathway in depressed patients, as well as its recently described role in the initiation of despair behaviors26, have made the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway particularly compelling as part of the potential mechanism mediating the microbiome effects on behavior. IDO1 is the main enzyme metabolizing L-tryptophan to kynurenine outside of the liver (where TDO is the primary enzyme)27. The effects of Lactobacillus strains on ido1 expression remain unclear. While it appears that in the context of inflammatory disease several Lactobacillus strains can increase IDO1 expression or activity28,29, in other models Lactobacillus administration dampens it30,31. Intriguingly, a recent study32 showed that, at steady state, Lactobacillus administration can directly modulate kynurenine metabolism, by inhibiting the pathway initiating enzyme IDO1 via production of reactive oxygen species (i.e. H2O2, summarized in Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Lactobacillus supplementation improves behavior by moderating kynurenine metabolism.

(a) Representation of tryptophan-kynurenine pathway, depicting H2O2 inhibition of pathway-initiating enzyme IDO1. (b) Production of H2O2 by E. coli and L. reuteri (n = 3 wells per group; representative of 2 independent experiments; two-tailed t-test, ***p < 0.001; mean ± s.e.m.). (c) Production of H2O2 by endogenous Lactobacillus species compared to L. reuteri (n = 7–8 colonies per group; one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s multiple comparisons, ***p < 0.001; mean ± s.e.m.). (d) Fecal H2O2 levels in naïve, stressed and L. reuteri treated stressed mice (n = 10 naïve, 11 stressed and 7 stressed + L.reuteri mice per group; one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s multiple comparisons, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; mean ± s.e.m.). (e) Correlation between Lactobacillus and H2O2 levels in naïve and stressed mice (n = 5 mice per group; Spearman r test, **p = 0.01). (f) qRT-PCR quantification of ido1 expression in the intestines of naïve, stressed mice and L. reuteri treated stressed mice, relative to GAPDH. (n = 4 naïve, 7 stressed and stressed + L.reuteri mice per group, 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc, p < 0.01; mean ± s.e.m.). (g) Experimental design of L. reuteri and/or kynurenine administration. (h) Forced swim test quantification of escape behavior of naïve mice treated with L-kynurenine or saline control (n = 10 saline and 8 L-kynurenine mice per group; representative of 2 independent experiments; two-tailed t test with Welch’s correction, *p < 0.05; mean ± s.e.m.). (i) Forced swim test quantification of escape behavior of stressed mice treated with either L. reuteri alone or L. reuteri and L-kynurenine (n = 7 per group; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc, **p < 0.01; mean ± s.e.m.).

To further explore this question in our study, we verified that cultured L. reuteri produced a significant amount of H2O2 in vitro, when compared to E.coli, a negative control that does not produce H2O2 (Fig. 4b, t(4) = 208.2, p < 0.0001). In addition, we also compared the ROS production from L. reuteri with that of endogenous Lactobacillus in Jackson C57BL6 mice, L. johnsonii, and observed they were comparable (Fig. 4c and Sup. Fig. 3c, Tuckey’s posthoc q = 1.592, p = 0.51). L. murinus, the endogenous Lactobacillus found in Taconic C57BL6/N mice was also included for comparison. We next measured peroxide levels in the fecal contents of the stressed mice and discovered that H2O2 levels were decreased in the stressed mice; more importantly, and in agreement with our hypothesis, therapeutic administration of L. reuteri significantly raised the level of H2O2 in vivo (F(2, 25) = 9.907, p = 0.0007, Fig. 4d). Moreover, we observed a significant correlation between the drop in Lactobacillus levels and the levels of H2O2 (Fig. 4e, Spearman r = 0.7818, p = 0.0105). We further verified the kynurenine pathway dysregulation by probing for ido1 mRNA in the intestine. Our results show increased ido1 expression in the intestines after stress, which is decreased after L. reuteri treatment (Fstress(2, 14) = 7.274, p = 0.0068), in accordance to the effects observed on ROS production (Fig. 4f). To further investigate the causative role of kynurenine metabolism in mediating despair behavior we treated naïve mice with L-kynurenine daily (i.p., Fig. 4g) and observed a significant reduction in escape behavior (t(16) = 2.861, Welch’s correction applied, p = 0.0113) at the end of the 4-week protocol (Fig. 4h). Moreover, in order to show that the benefit of Lactobacillus supplementation is by reducing kynurenine level, we treated stressed mice simultaneously with L.reuteri and L-kynurenine, expecting kynurenine to bypass the benefits of L.reuteri supplementation. Indeed, while L. reuteri alone increased the escape behavior of stressed mice, kynurenine administration abrogated the beneficial effect of L.reuteri (F(2, 18) = 8.632, p = 0.0024; Fig. 4i), even with elevated levels of Lactobacillus and H2O2 (Sup. Fig. 7a,b).

Discussion

Taken together, our results demonstrate that microbiome homeostasis was robustly altered in animals undergoing UCMS, with a consistent decrease in Lactobacilli. This finding was shared across three strains of mice (C57BL/6J, as BALB/cJ and C57BL/6N). Moreover, our data suggest that the production of H2O2 by Lactobacillus may be protective against the development of despair behavior by direct inhibition of intestinal ido1 expression and decrease in the circulating level of kynurenine, a metabolite associated with depression26.

Our results are in agreement with recent literature demonstrating that microbiome composition is modified with acute and chronic stress20,33,34. Microbiome dysbiosis is also detected in humans affected by major depressive disorders and the transplantation of the biota from these patients in germ free mice can induce despair behavior9. Beyond describing microbiome fluctuation as a consequence of UCMS, we further demonstrated that levels of Lactobacillus correlate with the susceptibility to and severity of despair behaviors. Indeed, animals exhibiting low (i.e. Taconic C57BL/6N mice) intestinal Lactobacillus levels present with a basal despair phenotype, when compared to animals with higher levels of Lactobacillus (i.e. Jackson C57BL/6J mice). Accordingly, therapeutic administration of a probiotic Lactobacillus species during UCMS was sufficient to improve the despair symptoms. Further works will be needed to explore the role of other populations of bacteria affected by UCMS, as well as Lactobacillus strain differences and their abilities to improve behavior.

Recently, members of the Lactobacillus genus have been shown to affect a multitude of aspects of human physiology, as they colonize several sites of the body, including the skin, the vagina, and the entirety of the gastrointestinal tract, starting with the oral cavity35. Perhaps best studied in the vagina, Lactobacilli protect against infection by producing a diversity of antimicrobial factors, including lactic acid, peroxide, bacteriocins, as well as by resource competition35,36,37. Although in a few contexts increased levels of Lactobacilli are associated with pathology, e.g. dental cavities38, the bacteria are largely non-pathogenic or beneficial. From dysbioses or probiotic studies, Lactobacilli are associated with protection against infection, improved recovery after enteric infections, decreased colitis pathology, and better cognitive function25,39,40,41.

While Lactobacilli are able to control other microbial communities through secretion of antimicrobial factors, genetic limitations make them more sensitive to environmental conditions. In particular, many Lactobacillus genus members are unable to synthesize amino acids and purines and thus rely on nutrient rich environments and other bacteria for supply of essential building blocks42,43,44,45. We hypothesize that, in the context of a faster intestinal transit, such as the one observed in stressed animals, fluctuating availability of nutrients and symbiotic bacteria will impact the renewal of the Lactobacillus niche46. Further studies will be able to determine whether there is indeed a causal relationship between increased intestinal motility and microbiota alteration in the context of stress, or rather if the dysbiosis induced during stress causes altered intestinal physiology.

We found that the level of kynurenine is increased after chronic stress, in a manner dependent on Lactobacillus levels. Kynurenine can readily cross the blood-brain barrier to drive depression within the CNS by disrupting neurotransmitter balance and driving neuroinflammation27,47. A recent study by Agudelo et al.26 identified this pathway as also being disrupted in stressed mice using the same model of UCMS. Taken together, these new findings point to disruptions in tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism as an important factor in mediating despair behavior. IDO1 is the main enzyme responsible for conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine outside of the liver, and its expression and activity can be directly inhibited by reactive oxygen species (ROS)32. Members of the Lactobacillus family have the capacity to produce high levels of ROS, as a means of maintaining their niche36,37. In our study, we have shown that decreased levels of ROS in stressed animals correlate with an increase in intestinal ido1 transcripts, thus potentially explaining our observed increase in circulating kynurenine. Moreover, several studies have shown that inhibiting IDO1 activity (such as with the small molecule 1-methyl tryptophan) has potent effects in ameliorating depressive-like behaviors both in chronic stress and inflammation-induced sickness behavior models48,49,50.

The inhibition of IDO1 by Lactobacillus-derived ROS is likely just one of the mechanisms through which Lactobacilli, and L. reuteri in particular, contribute to host physiology and modulate behavior. Our findings are in accordance with the previously reported beneficial effect of L. reuteri administration on despair and anxiety-like behaviors25. Nevertheless, in their study, Bravo and colleagues have shown that L. reuteri can modulate GABA receptor expression in the CNS, via the vagus nerve25. The vagus nerve has been shown to carry peripheral signals and modulate inflammatory and stress reponses51,52,53,54. Whether the two results are connected remains to be investigated. It is possible that intestinal kynurenine can signal on the afferent vagal terminals and modulate its effects in the CNS, including its modulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. To this point, it is important to consider the contribution of liver TDO to peripheral kynurenine levels. TDO expression and activity are increased by glucocorticoids and in response to acute stress, and play a role in glucocorticoid levels homeostasis55,56,57. Whether TDO levels decrease chronically in our long-term stress model (following an expected decrease of corticosterone) or what effect the Lactobacillus administration has remains to be investigated. We have also considered other possible mechanisms for the behavioral effects of L. reuteri supplementation, mediated by the immune system, or other populations of commensals affected by the treatment. Further studies will be necessary to assess the chronological and the hierarchical role of each pathway during despair behavior development, as well as how these pathways affect the CNS.

Altogether, our results indicate that the microbiome can play a causative role in the development and symptomatology of depression. Further studies are needed to prove a causal relationship between intestinal Lactobacillus levels and depressive-like behavior. Moreover, investigation of whether Lactobacilli can play a similar function in human biology and if manipulation of Lactobacillus levels and/or local induction of ROS production in the gut could be used to treat psychiatric disorders is warranted.

Methods and Materials

Animals

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the University of Virginia and approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 and BALB/c (8 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson or Taconic laboratories as described in the text. The mice were maintained on a 12 hours light/dark cycle with lights on at 7am. Chronic stress was started after at least 1 week of acclimation. All behavioral interventions were performed between 4 pm and 7 pm and take-downs were performed between 11am and 2 pm. Sample size was selected to be similar to previously reported behavioral experiments. Animals were housed 2–3 per cage and cages were randomly assigned to control or experimental groups. In each experiment, every group consisted of at least 3 cages in order to minimize cage effects. Investigators were not blinded to the group allocation. Experiments were conducted in such a way as to make sure that all experimental groups were exposed to the same environments. Animals were excluded from the experiments if they developed illnesses (e.g. dermatitis) that might affect the outcome of the results. Certain measurements are occasionally not available for each mouse enrolled in the study due to technical issues (e.g. fecal sample not provided, sample loss).

Chronic mild stress protocol

Mice were subjected daily to an acute stressor (1–2 hours: restraint, loud white noise, crowded housing, strobe light) and an overnight stressor (12–24 hours: 45° cage tilting, repeated cage changes, wet bedding, dark deprivation) presented in a randomized fashion as described in the literature13. For restraint stress, mice were placed in clean 50 mL conical tubes with pierced holes for ventilation for 1 hour. For crowded housing stress, mice were placed on top of the cage wire for 2 hours, after which their cage was changed. For wet bedding stress, 200 mL of water was added to the bedding of a clean cage. All procedures used autoclaved, sterile materials (bedding, water) in order to prevent contamination. Food, water intake, and weights were monitored in initial experiments and no major changes were observed in the stressed group. For subsequent experiments, monitored parameters are indicated on matching experimental design figures. Sequencing results showed no new OTUs in the stressed microbiota, indicating the lack of contamination during the stress protocol.

Behavioral assessment

Despair behavior was assessed at time points of interest using the forced swim test, as described in the literature58. The last 4 minutes (out of 6 minutes total test) were scored for escape behavior, defined as active swimming, with all four limbs and tail moving. The test was conducted using autoclaved water and disinfected containers. Anxiety/compulsive behavior was assessed using the nestlet-shredding test16. The mice were singled housed 30–60 minutes before the beginning of the test. Each mouse then received a pre-weighed nestlet and allowed undisturbed activity for either 30 or 60 minutes. At the end of the test, the piece of nestlet that was still intact was weighed.

DNA isolation

Whole genomic DNA was isolated via phenol-chloroform extraction. Briefly, a fecal pellet was placed in a 2 mL tube containing 200 μL silica-zirconia beads (0.1 mm). The tube was filled with 750 μL extraction buffer, 200 μL 20% SDS and 750 μL phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). After disruption, the aqueous phase was separated by centrifugation and cleaned up with two washes of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). The DNA was precipitated and resuspended in 10 mM Tris solution.

Fecal microbiota sequencing

For 16S rRNA sequencing, the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified for 25 cycles using specific primers with adapter overhangs as per the Illumina library preparation guide (Sup. Table 1). Following purification of the PCR products, individual indexes were added to the amplicons by PCR. The amplicons were purified, pooled in equal quantities, and then sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Reads with an average quality score below 25 (from any 10-bp window) or a mismatched barcode were removed. Paired-end reads were then merged using the software FLASH59. Merged reads were analyzed using the QIIME pipeline with default parameters to remove chimeric, pick 97%-identity OTUs and assign taxonomy60.

Selective culture of Lactobacilli and L. reuteri preparation

Fecal pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of deMan, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth supplemented with sodium azide (0.02% w/v) to select Lactobacillus19. After brief decanting of insoluble fecal material, samples were further diluted 1:1000 in MRS/azide and 50 μL of this dilution were spread on MRS/azide agar plates and grown overnight at 37 °C, in aerobic conditions. The plates were then imaged with a Bio-Rad gel imager and colonies were counted using the “particle counter” plugin in ImageJ.

For Lactobacillus supplementation experiments, L. reuteri was obtained from ATCC (23272) and cultured aerobically according to manufacturer instructions. Radiated food pellets were pulverized in a blender and kneaded with fresh L. reuteri (2 billion CFU/mouse/day) and water, or with MRS culture broth and water for control. The animals received fresh food prepared daily.

Intestinal transit time measurement

Large intestinal transit time was measured as previously described61. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and a 3 mm diameter glass bead was inserted 2 cm inside the rectum with a lubricated rod. The mice were then placed in an empty cage without bedding and the time to bead expulsion was measured.

Intestinal tissue analysis

The small intestine was dissected by excising under the stomach and before the cecum. Mesenteric fat and Peyer’s patches were carefully removed using fine forceps. The intestine was opened longitudinally and the contents were removed in two PBS washes. Excess liquid was gently absorbed using kimwipes and the tissue was weighed. Intestinal cells were then isolated as previously described62. Briefly, the mucus layer and epithelial cells were shook off in two washes with HBSS/5% FBS/2 mM EDTA. The tissue was then digested with collagenase VIII (Sigma, C2139) for 12–15 minutes, filtered, and the cells washed twice with HBSS/5% FBS/2 mM EDTA and finally resuspended in FACS buffer (0.01 M PBS, 1% BSA, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% sodium azide). Cell counts and viability were determined using an acridine orange/propidium iodine assay on a Nexcelom cell counter.

Metabolite analysis

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 3 minutes in gel tubes for serum preparation. Frozen (−80 °C) serum samples were shipped to the University of Michigan Metabolomics Core for untargeted metabolomics analysis. Metabolites isolated by positive and negative ion selection were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry peak intensities were further analyzed using the MetaboAnalyst online software. Peak values were filtered using the interquantile range, normalized to the group sum, then log transformed and auto-scaled for principal component analysis and further statistical tests63. Identifiable significant metabolites were analyzed through pathway analysis, followed by further manual pathway enrichment.

ROS quantification

Fresh fecal samples were collected in sterile 2 mL tubes, weighed, and resuspended in 1 mL sterile PBS. After brief sedimentation of insoluble particles, 500 μL of bacterial slurry were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Following bacterial culture centrifugation, 50 μL of supernatant was reacted using the Amplex Red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit (Thermo Fisher, cat. A22188) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For ROS production by individual Lactobacillus species, fecal Lactobacilli were cultured as described above for 20 hours. Individual colonies were selected and dissociated in 200 uL MRS media and incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The resulting ROS concentration was measured as described above. The identity of each colony was verified using specific primers (Sup. Table 1).

qPCR

For RNA quantification, frozen tissues (brain and intestine) were homogenized by bead beating in RNA TRI Reagent (Life technologies) and RNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthethized with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies). cDNA was amplified using the Sensifast Sybr NO-ROX kit (Bioline), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Gapdh was measured as a normalizer for each sample. Results were analyzed by the relative quantity (ΔΔCt) method64.

For total 16S rRNA quantification, we followed the BactQuant protocol described by Liu et al.65. Briefly, the 16S gene was amplified using primers directed to the V3-V4 rRNA region (Sup. Table 1). L. reuteri DNA was used for the standard curve. For relative quantification of total Lactobacillus or specific Lactobacillus species, the ΔΔCt method was used to compare Lactobacillus-specific amplification to that of the 16S rRNA gene. Reactions were performed using the Sensifast Sybr NoROX kit from Bioline (BIO-98005). Primer sequences are available in Sup. Table 1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Prism. The results of the statistical tests are presented within the results section. Analyses involving two groups were performed using a two-tailed t-test. If the variances between groups were significantly different, a Welch’s correction was applied. For experiments involving stress and another variable (e.g. L.reuteri treatment), data were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA. For the metabolomics experiments involving only 3 groups, a one-way ANOVA was utilized. Outliers were excluded if they fell more than two standard deviations from the mean. For all analyses, the threshold for significance was at p < 0.05. Repeats for each experiment, if performed, are specified in the figure legend corresponding to the respective panel.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Marin, I. A. et al. Microbiota alteration is associated with the development of stress-induced despair behavior. Sci. Rep. 7, 43859; doi: 10.1038/srep43859 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our research groups and the members of the BIG center for numerous discussions of this work. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the University of Michigan Metabolomics Core for conducting our metabolomics analysis. The authors are supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (USA) R21 MH108156 and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society PP1412.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions I.A.M. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.E.G. assisted with and performed experiments. T.R., M.W. and C.O. assisted with and performed sequencing experiments and analyzed the sequencing data. S.S.R., S.O.G. and E.F. assisted with and performed sequencing experiments. A.G. and J.K. assisted with experimental design, guidance, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Southwick S. M., Vythilingam M. & Charney D. S. The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: implications for prevention and treatment. Annual review of clinical psychology 1, 255–291, doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer D. J., Frank E. & Phillips M. L. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet 379, 1045–1055, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60602-8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V. & Nestler E. J. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 455, 894–902, doi: 10.1038/nature07455 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J. et al. The human microbiome project. Nature 449, 804–810, doi: 10.1038/nature06244 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Heijtz R. et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 3047–3052, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld K. M., Kang N., Bienenstock J. & Foster J. A. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 23, 255–264, e119, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01620.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino R. et al. Commensal microbiota modulate murine behaviors in a strictly contamination-free environment confirmed by culture-based methods. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 25, 521–528, doi: 10.1111/nmo.12110 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung W. S. et al. Astrocytes mediate synapse elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK pathways. Nature 504, 394–400, doi: 10.1038/nature12776 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P. et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Molecular psychiatry 21, 786–796, doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthakrishnan A. N. et al. Association between depressive symptoms and incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 11, 57–62, doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.032 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodhand J. R. et al. Mood disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: relation to diagnosis, disease activity, perceived stress, and other factors. Inflammatory bowel diseases 18, 2301–2309, doi: 10.1002/ibd.22916 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S. et al. Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. The American journal of gastroenterology 95, 1213–1220, doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02012.x (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollet M., Le Guisquet A. M. & Belzung C. Models of depression: unpredictable chronic mild stress in mice. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter 5, Unit 5 65, doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0565s61 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 134, 319–329 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur Y. S., Belzung C. & Crusio W. E. Effects of unpredictable chronic mild stress on anxiety and depression-like behavior in mice. Behav Brain Res 175, 43–50, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.029 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Morrow D. & Witkin J. M. Decreases in nestlet shredding of mice by serotonin uptake inhibitors: comparison with marble burying. Life Sci 78, 1933–1939, doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.08.002 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy Y. E. et al. Variation in Taxonomic Composition of the Fecal Microbiota in an Inbred Mouse Strain across Individuals and Time. PLoS One 10, e0142825, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142825 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson A. C. et al. Effects of vendor and genetic background on the composition of the fecal microbiota of inbred mice. PLoS One 10, e0116704, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116704 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn Y. T. et al. Characterization of Lactobacillus acidophilus isolated from piglets and chicken. Asian Austral J Anim 15, 1790–1797 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Galley J. D. et al. Exposure to a social stressor disrupts the community structure of the colonic mucosa-associated microbiota. BMC microbiology 14, 189, doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-189 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasarevic E., Howerton C. L., Howard C. D. & Bale T. L. Alterations in the Vaginal Microbiome by Maternal Stress Are Associated With Metabolic Reprogramming of the Offspring Gut and Brain. Endocrinology 156, 3265–3276, doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1177 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al. Actions of hydrogen sulfide and ATP-sensitive potassium channels on colonic hypermotility in a rat model of chronic stress. PLoS One 8, e55853, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055853 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnett N. W. The stressed gut: contributions of intestinal stress peptides to inflammation and motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 7409–7410, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503092102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh P. L. et al. Diversification of the gut symbiont Lactobacillus reuteri as a result of host-driven evolution. The ISME journal 4, 377–387, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.123 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo J. A. et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 16050–16055, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo L. Z. et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1alpha1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress-induced depression. Cell 159, 33–45, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.051 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz R., Bruno J. P., Muchowski P. J. & Wu H. Q. Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 465–477, doi: 10.1038/nrn3257 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe P., Inman M. D. & Bienenstock J. Oral treatment with live Lactobacillus reuteri inhibits the allergic airway response in mice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 175, 561–569, doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-821OC (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue T., Atarashi K. & Honda K. Development and maintenance of intestinal regulatory T cells. Nature Reviews Immunology 16, 295–309, doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.36 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujkovic-Cvijin I. et al. Gut-Resident Lactobacillus Abundance Associates with IDO1 Inhibition and Th17 Dynamics in SIV-Infected Macaques. Cell reports 13, 1589–1597, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.026 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K. et al. Inhibition of Type 1 Diabetes Correlated to a Lactobacillus johnsonii N6.2-Mediated Th17 Bias. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001864 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Valladares R. et al. Lactobacillus johnsonii inhibits indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and alters tryptophan metabolite levels in BioBreeding rats. FASEB J 27, 1711–1720, doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223339 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasarevic E., Rodgers A. B. & Bale T. L. A novel role for maternal stress and microbial transmission in early life programming and neurodevelopment. Neurobiology of stress 1, 81–88, doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma G. et al. Microbiota and host determinants of behavioural phenotype in maternally separated mice. Nature communications 6, 7735, doi: 10.1038/ncomms8735 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan J. & O’Toole P. W. Lactobacillus: host-microbe relationships. Current topics in microbiology and immunology 358, 119–154, doi: 10.1007/82_2011_187 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil N. F., Martinez R. C., Gomes B. C., Nomizo A. & De Martinis E. C. Vaginal lactobacilli as potential probiotics against Candida SPP. Brazilian journal of microbiology: [publication of the Brazilian Society for Microbiology] 41, 6–14, doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000100002 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberger R. et al. H(2)O(2) production in species of the Lactobacillus acidophilus group: a central role for a novel NADH-dependent flavin reductase. Appl Environ Microbiol 80, 2229–2239, doi: 10.1128/AEM.04272-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badet C. & Thebaud N. B. Ecology of lactobacilli in the oral cavity: a review of literature. The open microbiology journal 2, 38–48, doi: 10.2174/1874285800802010038 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. & Van Hul M. Novel opportunities for next-generation probiotics targeting metabolic syndrome. Current opinion in biotechnology 32, 21–27, doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.10.006 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J., Britton R. A. & Roos S. Host-microbial symbiosis in the vertebrate gastrointestinal tract and the Lactobacillus reuteri paradigm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, Suppl 1, 4645–4652, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000099107 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. A. & McVey Neufeld K. A. Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci 36, 305–312, doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altermann E. et al. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 3906–3912, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409188102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant R., Blom J., Palva A., Siezen R. J. & de Vos W. M. Comparative genomics of Lactobacillus. Microbial biotechnology 4, 323–332, doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00215.x (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H. et al. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103. Journal of bacteriology 191, 7630–7631, doi: 10.1128/JB.01287-09 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridmore R. D. et al. The genome sequence of the probiotic intestinal bacterium Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 2512–2517 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen A. M., Wiggins H. S. & Cummings J. H. Effect of changing transit time on colonic microbial metabolism in man. Gut 28, 601–609 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L., Szalardy L., Fulop F. & Toldi J. Kynurenines in the CNS: recent advances and new questions. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12, 64–82, doi: 10.1038/nrd3793 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. et al. Brain indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase contributes to the comorbidity of pain and depression. J Clin Invest 122, 2940–2954, doi: 10.1172/JCI61884 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobos N. et al. The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in a mouse model of neuroinflammation-induced depression. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 28, 905–915, doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111097 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugeray A. et al. Chronic Treatment with the IDO1 Inhibitor 1-Methyl-D-Tryptophan Minimizes the Behavioural and Biochemical Abnormalities Induced by Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress in Mice - Comparison with Fluoxetine. PLoS One 11, e0164337, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164337 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler L. E., Gaykema R. P., Hammack S. E., Maier S. F. & Watkins L. R. Interleukin-1 induces c-Fos immunoreactivity in primary afferent neurons of the vagus nerve. Brain Res 804, 306–310, doi: S0006-8993(98)00685-4 [pii] (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovikova L. V. et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature 405, 458–462, doi: 10.1038/35013070 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mravec B., Ondicova K., Tillinger A. & Pecenak J. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy enhances stress-induced epinephrine release in rats. Autonomic neuroscience: basic & clinical 190, 20–25, doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.04.003 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmaga H., Carreno F. R. & Frazer A. Vagal nerve stimulation rapidly activates brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptor TrkB in rat brain. PLoS One 7, e34844, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034844 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesch U. et al. Glucocorticoid induction of the rat tryptophan oxygenase gene is mediated by two widely separated glucocorticoid-responsive elements. EMBO J 6, 625–630 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesch U., Hashimoto S., Renkawitz R. & Schutz G. Transcriptional regulation of the tryptophan oxygenase gene in rat liver by glucocorticoids. J Biol Chem 258, 4750–4753 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta Y. et al. Effect of water-immersion restraint stress on tryptophan catabolism through the kynurenine pathway in rat tissues. The journal of physiological sciences: JPS, doi: 10.1007/s12576-016-0467-y (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergner C. L. et al. Mouse models for studying depression-like states and antidepressant drugs. Methods Mol Biol 602, 267–282, doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-058-8_16 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoc T. & Salzberg S. L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods 7, 335–336, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilz T. O. et al. Functional assessment of intestinal motility and gut wall inflammation in rodents: analyses in a standardized model of intestinal manipulation. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE, doi: 10.3791/4086 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geem D., Medina-Contreras O., Kim W., Huang C. S. & Denning T. L. Isolation and characterization of dendritic cells and macrophages from the mouse intestine. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE, e4040, doi: 10.3791/4040 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J. & Wishart D. S. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat Protoc 6, 743–760, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thellin O. et al. Housekeeping genes as internal standards: use and limits. J Biotechnol 75, 291–295 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. M. et al. BactQuant: an enhanced broad-coverage bacterial quantitative real-time PCR assay. BMC microbiology 12, 56, doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-56 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.