Abstract

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) is a prevalent modification present in the mRNAs of higher eukaryotes. YTH domain family 2 (YTHDF2), an m6A “reader” protein, can recognize mRNA m6A sites to mediate mRNA degradation. However, the regulatory mechanism of YTHDF2 is poorly understood. To this end, we investigated the post-transcriptional regulation of YTHDF2. Bioinformatics analysis suggested that the microRNA miR-145 might target the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of YTHDF2 mRNA. The levels of miR-145 were negatively correlated with those of YTHDF2 mRNA in clinical hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues, and immunohistochemical staining revealed that YTHDF2 was closely associated with malignancy of HCC. Interestingly, miR-145 decreased the luciferase activities of 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA. Mutation of predicted miR-145 binding sites in the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA abolished the miR-145-induced decrease in luciferase activity. Overexpression of miR-145 dose-dependently down-regulated YTHDF2 expression in HCC cells at the levels of both mRNA and protein. Conversely, inhibition of miR-145 resulted in the up-regulation of YTHDF2 in the cells. Dot blot analysis and immunofluorescence staining revealed that the overexpression of miR-145 strongly increased m6A levels relative to those in control HCC cells, and this increase could be blocked by YTHDF2 overexpression. Moreover, miR-145 inhibition strongly decreased m6A levels, which were rescued by treatment with a small interfering RNA-based YTHDF2 knockdown. Thus, we conclude that miR-145 modulates m6A levels by targeting the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA in HCC cells.

Keywords: microRNA (miRNA), microRNA mechanism, mRNA decay, RNA methylation, RNA modification, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), YTH domain family 2 (YTHDF2), mRNA degradation, miR-145

Introduction

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A)3 is a common modification of RNA molecules. There are about 7600 mRNA transcripts, and more than 300 non-coding RNAs contain the m6A sites in humans (1, 2). Although the modification exists widely, the biological importance of m6A remains largely unknown (3, 4). m6A modification has been reported to function in mRNA splicing, export, and stability and so on. Many enzymes are involved in the m6A system, such as the methylases methyltransferase-like 3 (mettl3)/mettl14, demethylases fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO)/alkB homolog 5(ALKBH5) (5–7). Moreover, the methylases and demethylases of m6A have been shown to have disease correlations (1, 5, 8–10). Among the enzymes involved in the system, YTH domain family 1 (YTHDF1) and YTH domain family 2 (YTHDF2) are demonstrated selectively binding m6A sites as reader proteins. YTHDF1 can regulate mRNA translation efficiency, whereas YTHDF2 is reported to have influence in regulating mRNA degradation and cell viability (11–13). In addition, YTHDF2 gene has been found associated with human longevity (14). Thus, YTHDF2 has more important biological functions and plays significant roles in m6A regulation system. However, the regulatory mechanism of YTHDF2 is not well documented.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous 21–24 nucleotides RNAs that can play significant regulatory roles by targeting mRNAs for cleavage or translational repression. In mammals, the miRNAs introduce the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of mRNA targets, and the translation of the mRNAs is impeded by base complementary (15–17). MiRNAs post-transcriptionally repress gene expression by base pairing to mRNAs. More than half of all mRNAs are estimated to be targets of miRNAs, and each miRNA is predicted to regulate about hundreds of targets (18–20). miR-145 is a famous miRNA with many biological functions. The current study demonstrates that miR-145 is involved in the different diseases, such as cardiac myofibroblast differentiation, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and microvasculature (21–23). In addition, miR-145 is also associated with different kinds of human cancers, in which miR-145 regulates PAK4 in human colon cells and is down-regulated in human ovarian cancer and so on (24–26). miR-145 is known to inhibit proliferation of prostate, renal, and esophageal cancer (27–29). Moreover, miRNA-145 is down-regulated in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (30, 31). It is reported that miR-145 can inhibit HCC through targeting IRS1 and its downstream effectors (32).

In this study we investigated the regulatory mechanism of YTHDF2 in liver cancer cells. Interestingly, we identified that miR-145 was involved in targeting YTHDF2 mRNA in the regulation of mRNA m6A. Our finding provides new insights into the regulatory mechanism of YTHDF2 in mRNA methylation.

Results

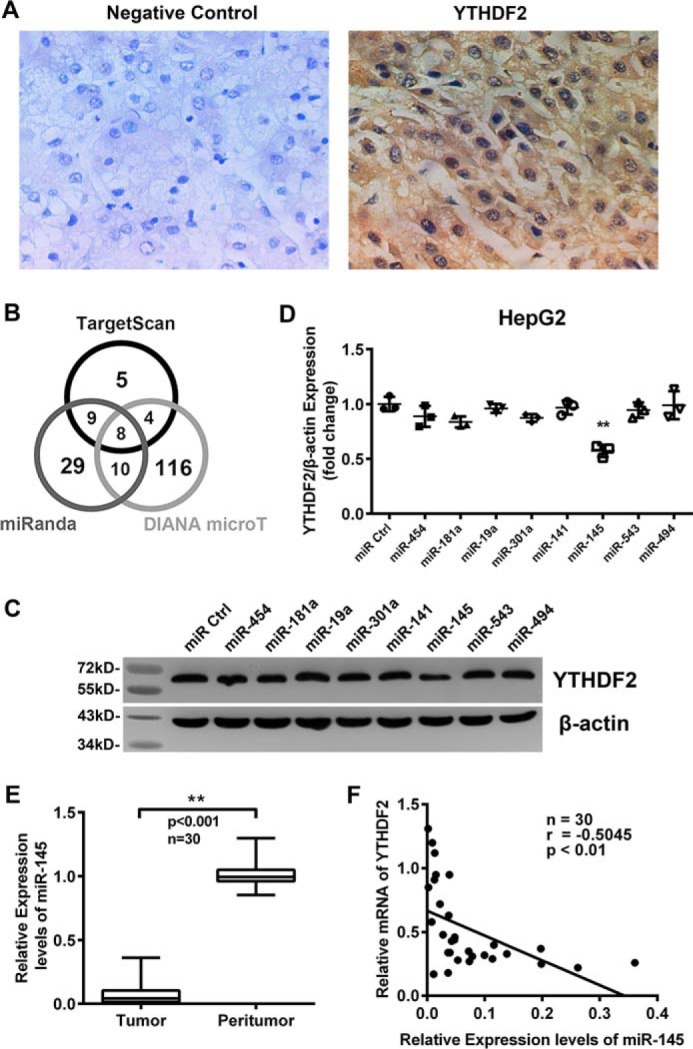

The Expression Levels of miR-145 Are Negatively Correlated with Those of YTHDF2 in Clinical HCC Tissues

It has been reported that YTHDF2 plays significant roles in m6A regulation systems. However, the significance of YTHDF2 in cancer is poorly understood. We examined the expression of YTHDF2 in clinical HCC tissues via immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining using tissue arrays. Our data revealed that the control group without treatment with anti-YTHDF2 antibody (Fig. 1A, left) was negative, suggesting that the specificity of the antibody was suitable for IHC staining. The test group (right) showed that the positive signals of YTHDF2 staining were located in the cytoplasm and nucleus in HCC tissues (Fig. 1). The positive rate of YTHDF2 was 35.6% (67/188) in the tissues, in which 83.9% (26/31) was in grade III HCC tissues, suggesting that YTHDF2 is closely associated with the malignance of HCC. Next, we investigated the post-transcriptional regulation YTHDF2. We focused on the effects of miRNAs on YTHDF2. Bioinformatics analysis predicted the potential miRNAs targeting the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 by using three websites, including DIANA-microT, Targetscan, and MiRanda (33). Interestingly, eight candidate miRNAs could be predicted (Fig. 1B). Among them, miR-145 had the highest score in all three websites. Western blot analysis screening showed that miR-145 could remarkably suppress the expression of YTHDF2 in HepG2 cells (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting that miR-145 is involved in the regulation of YTHDF2 mRNA. Then, real-time PCR revealed that the expression levels of miR-145 were significantly reduced in 30 clinical HCC samples relative to their adjacent peritumorous tissues (p < 0.001, n = 30; Wilcoxon's signed-rank test). The expression level of miR-145 was relative to U6 (Fig. 1E). Moreover, we observed that the expression levels of miR-145 were negatively correlated with those of YTHDF2 mRNA in HCC tissues (Pearson' correlation coefficient, r = −0.5045, p < 0.01; Fig. 1F). Thus, we conclude that YTHDF2 may be one of the target genes of miR-145.

FIGURE 1.

The expression levels of miR-145 are negatively correlated with those of YTHDF2 in clinical HCC tissues. A, expression of YTHDF2 was examined by IHC staining in clinical HCC tissues. B, schema of the candidate miRNAs by different prediction web. Each labeled circle represents one prediction websites with the number of its predicted miRNAs, and the number listed in overlapping of circles is simultaneously predicted by different web. C, Western blot analysis of YTHDF2 for HepG2 cells transiently transfected with miR ctrl, miR-454, miR-181a, miR-19a, miR-301a, miR-141, miR-145, miR-543, miR-494 mimic. D, expression of YTHDF2 relative to β-actin was quantified using ImageJ. Data are presented as -fold change in expression. E, relative expression levels of miR-145 were examined by qRT-PCR in 30 pairs of HCC tissues and corresponding peritumorous tissues (**, p < 0.01; Wilcoxon's signed-rank test). The experiments were repeated at least three times. F, correlation of levels of miR-145 with YTHDF2 mRNA levels was examined by qRT-PCR analysis in 30 cases of clinical HCC tissues (Pearson's correlation coefficient, r = −0.5045). Statistically significant differences are indicated: **, p < 0.01; Student's t test.

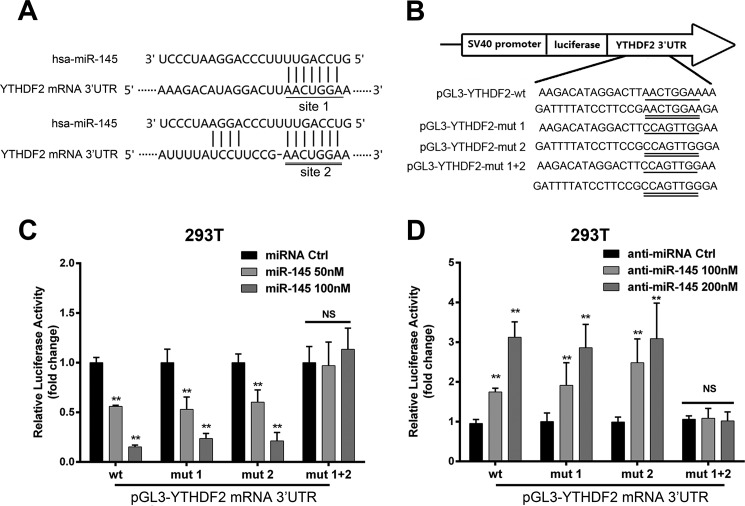

miR-145 Directly Targets 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA

Next, we tried to identify whether miR-145 could regulate YTHDF2 expression at post-transcriptional level. Bioinformatics analysis showed that there were two target sites of miR-145 in the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA (Fig. 2A). Then, we cloned the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA (termed pGL3-YTHDF2-WT) and its three mutants (termed pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1, pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 2, and pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1 + 2). The mutants were randomly designed following the principles that it could not produce another miR-145 binding site (Fig. 2B). Luciferase reporter gene assays elucidated that miR-145 could decrease the luciferase activities through targeting the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA in 293T cells. But it failed to work when both target sites were mutated in the cells (Fig. 2C). However, miR-145 inhibitor resulted in the opposite results (Fig. 2D), suggesting that YTHDF2 mRNA is one of the targets of miR-145. Collectively, we conclude that miR-145 directly targets the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA.

FIGURE 2.

miR-145 directly targets 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA. A, the binding sites of miR-145 in 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA was shown in a model. B, mutant was generated at 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA as indicated. A fragment of YTHDF2 mRNA 3′-UTR containing wild type (or mutants of the miR-145 binding sequence) was cloned into the downstream of the pGL3-control luciferase reporter gene vector. C, the effect of miR-145 on reporters, such as pGL3-YTHDF2-WT, pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1, pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 2, and pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1 + 2, was measured by luciferase reporter gene assays in 293T cells. D, the effect of anti-miR-145 on reporters, such as pGL3-YTHDF2-WT, pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1, pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 2, and pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1 + 2 was measured by luciferase reporter gene assays in 293T cells. Statistically significant differences are indicated: **, p < 0.01; NS, not significant. Student's t test. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

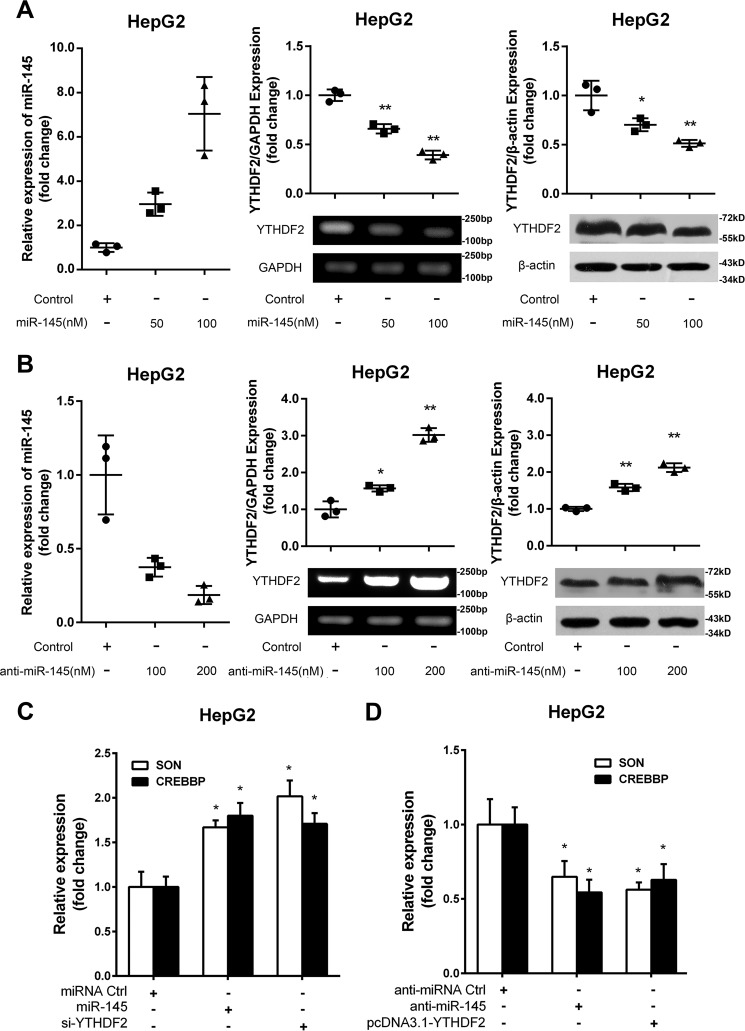

miR-145 Is Able to Down-regulate YTHDF2 in HepG2 Cells

To further validated the effect of miR-145 on the expression of YTHDF2, we performed the transient transfection of miR-145 in HepG2 cells. Interestingly, we observed that YTHDF2 was down-regulated in miR-145-overexpressed HepG2 cells at the levels of mRNA and protein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). The opposite results were obtained when the cells were treated with miR-145 inhibitor (Fig. 3B), suggesting that miR-145 is able to suppress the expression of YTHDF2 in HCC cells. In addition, the transfection efficiency of miR-145 and miR-145 inhibitor was validated by real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 3, A and B). It has been reported that YTHDF2 can down-regulate SON DNA binding protein (SON) and CREB-binding protein (CREBBP) (11). As expected, real-time PCR showed that miR-145 up-regulated the mRNA levels of SON and CREBBP in HepG2 cells. Meanwhile, si-YTHDF2 also worked well in the system (Fig. 3C). Conversely, anti-miR-145 down-regulated the mRNA levels of SON and CREBBP in the cells (Fig. 3D). Overexpression of YTHDF2 did well in the system, supporting that miR-145 is able to down-regulate YTHDF2 in HCC cells. We conclude that miR-145 is able to down-regulate YTHDF2 at the levels of mRNA and protein.

FIGURE 3.

miR-145 is able to down-regulate YTHDF2 in HepG2 cells. A, the transfection efficiency of miR-145 was validated by qRT-PCR analysis. The expression levels of YTHDF2 were examined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis in HepG2 cells transfected with miR-145 at the levels of mRNA and protein. The relative expression of YTHDF2 was quantified by using ImageJ. B, the transfection efficiency of miR-145 inhibitor was detected by qRT-PCR analysis. The levels of mRNA and protein of YTHDF2 were examined by RT-PCR analysis and Western blot analysis in HepG2 cells transfected with anti-miR-145. The relative expression of YTHDF2 was quantified by using ImageJ. C, the effect of miR-145 on SON and CREBBP was examined by qRT-PCR analysis in HepG2 cells. D, the effect of anti-miR-145 on SON and CREBBP was determined by qRT-PCR analysis in HepG2 cells. Statistically significant differences are indicated: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; Student's t test.

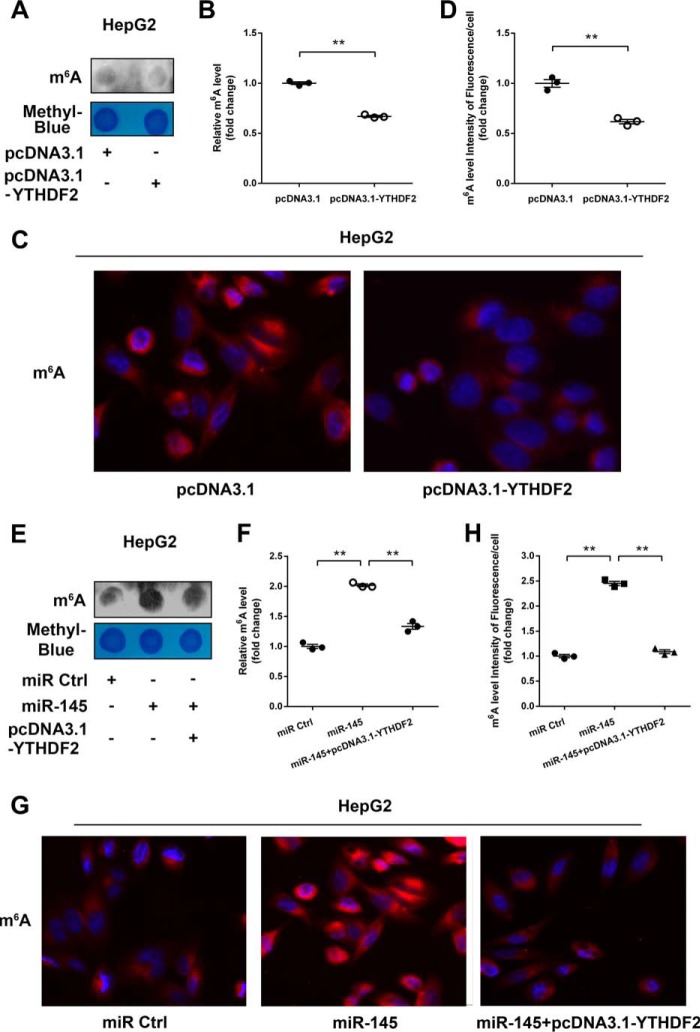

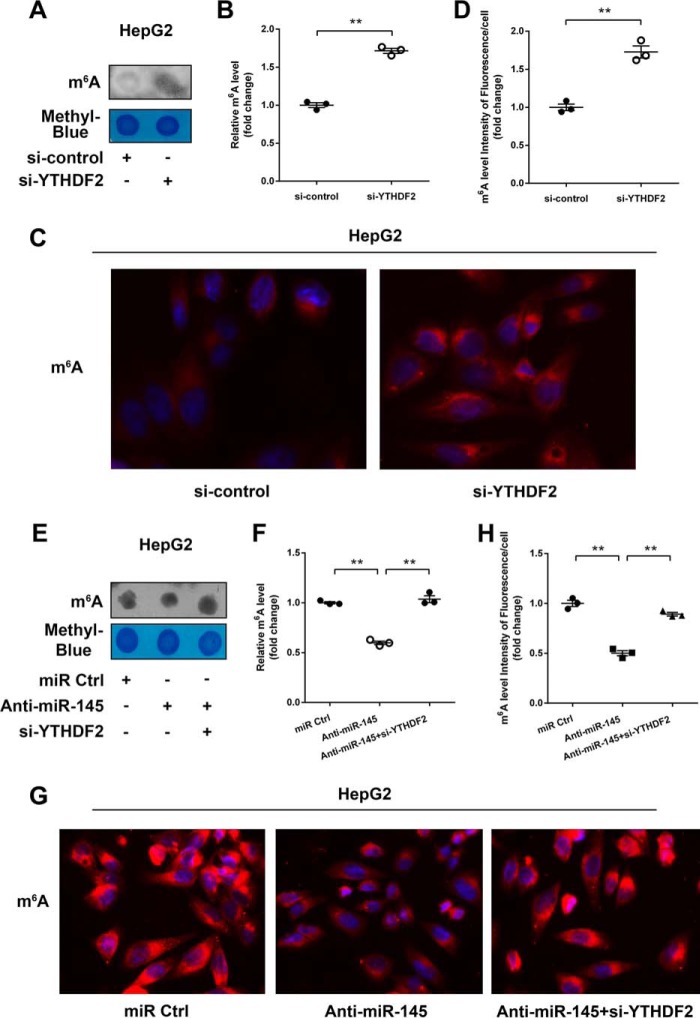

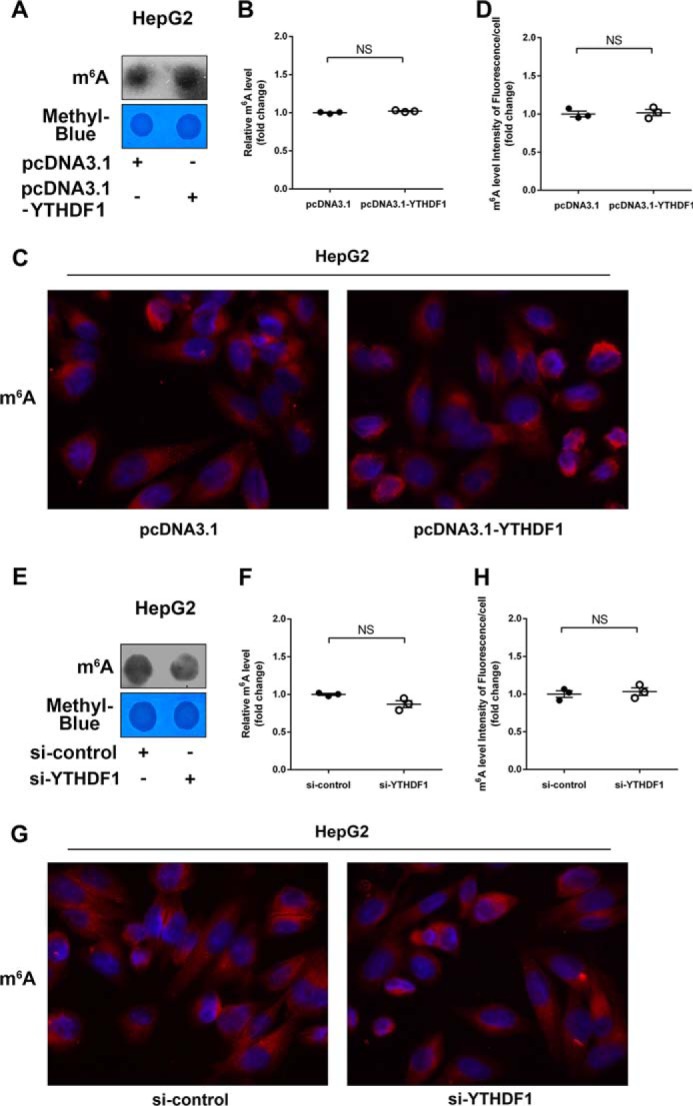

miR-145 Targets YTHDF2 and Increases the m6A Levels of mRNAs

Given that YTHDF2 can recognize mRNA m6A sites to mediate mRNA degradation (11, 13), the degradation of mRNAs can result in the decrease of m6A levels. Thereby, we were interested in whether miR-145 could affect m6A levels of mRNAs through modulating YTHDF2 in HCC cells. Dot blot assays revealed that overexpression of YTHDF2 could decrease the m6A levels of mRNAs in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Moreover, immunofluorescence staining validated the data (Fig. 4, C and D). Interestingly, we observed that miR-145 increased the m6A levels of mRNAs in the cells, which could be blocked by overexpression of YTHDF2 (Fig. 4, E and F). Immunofluorescence staining also confirmed the data (Fig. 4, G and H). Conversely, si-YTHDF2 led to the opposite results in the cells (Fig. 5A-D). But the treatment with miR-145 inhibitor could decrease the m6A levels of mRNAs, which could be rescued by si-YTHDF2 in the cells (Fig. 5, E--G), suggesting that miR-145 can increase the m6A levels of mRNAs through modulating YTHDF2. In addition, we also evaluated the effect of YTHDF1, a member of YTH domain family, on m6A levels of mRNAs. However, we failed to obtain the positive data (Fig. 6), suggesting that the YTHDF1 has no effect on the m6A levels of mRNAs in HepG2 cells. We conclude that miR-145 targeting YTHDF2 increases the m6A levels of mRNAs, which supports miR-145 as able to modulate YTHDF2.

FIGURE 4.

miR-145 increased the levels of mRNA m6A and blocked by YTHDF2. A, the mRNAs were isolated from HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-YTHDF2 followed by dot blot analysis with m6A antibody. The levels of m6A are shown in the upper panel. Equal loading of mRNAs was verified by methylene blue staining (lower panel). B, the quantification of m6A in A. C, immunofluorescence images of m6A (red) are shown. DAPI staining (blue) was included to visualize the nucleus. D, quantification of the intensity of fluorescence per cell of m6A levels in C. E, levels of m6A were shown in HepG2 cells transfected with miRNA control or miR-145 or both miR-145 and pcDNA3.1-YTHDF2. F, the quantification of m6A in E. G, immunofluorescence images of m6A (red) are shown. DAPI staining (blue) was included to visualize the nucleus. H, quantification of the intensity of fluorescence per cell of m6A levels in G. Statistically significant differences are indicated: **, p < 0.01; Student's t test.

FIGURE 5.

Anti-miR-145 decreased the levels of mRNA m6A and rescued by si-YTHDF2. A, the levels of m6A were measured by dot blot assays in HepG2 cells transfected with si-YTHDF2. B, the quantification of m6A in A. C, immunofluorescence images of m6A (red) are shown. DAPI staining (blue) was included to visualize the nucleus. D, the quantification of the intensity of fluorescence per cell of m6A levels in C. E, levels of m6A were shown in HepG2 cells transfected with miRNA control or miR-145 inhibitor or both miR-145 inhibitor and YTHDF2 siRNA. F, quantification of m6A in E. G, immunofluorescence images of m6A (red) are shown. DAPI staining (blue) was included to visualize the nucleus. H, the quantification of the intensity of fluorescence per cell of m6A levels in G. Statistically significant differences are indicated: **, p < 0.01; Student's t test.

FIGURE 6.

YTHDF1 had no effect on m6A levels of mRNAs. A, levels of m6A were measured by dot blot assays in HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-YTHDF1. B, quantification of m6A in A. C, immunofluorescence images of m6A (red) are shown. DAPI staining (blue) was included to visualize the nucleus. D, quantification of the intensity of fluorescence per cell of m6A levels in C. E, levels of m6A were measured by dot blot assays in HepG2 cells transfected with si-YTHDF1. F, quantification of m6A in E. G, immunofluorescence images of m6A (red) are shown. DAPI staining (blue) was included to visualize the nucleus. H, quantification of the intensity of fluorescence per cell of m6A levels in G. NS, not significant.

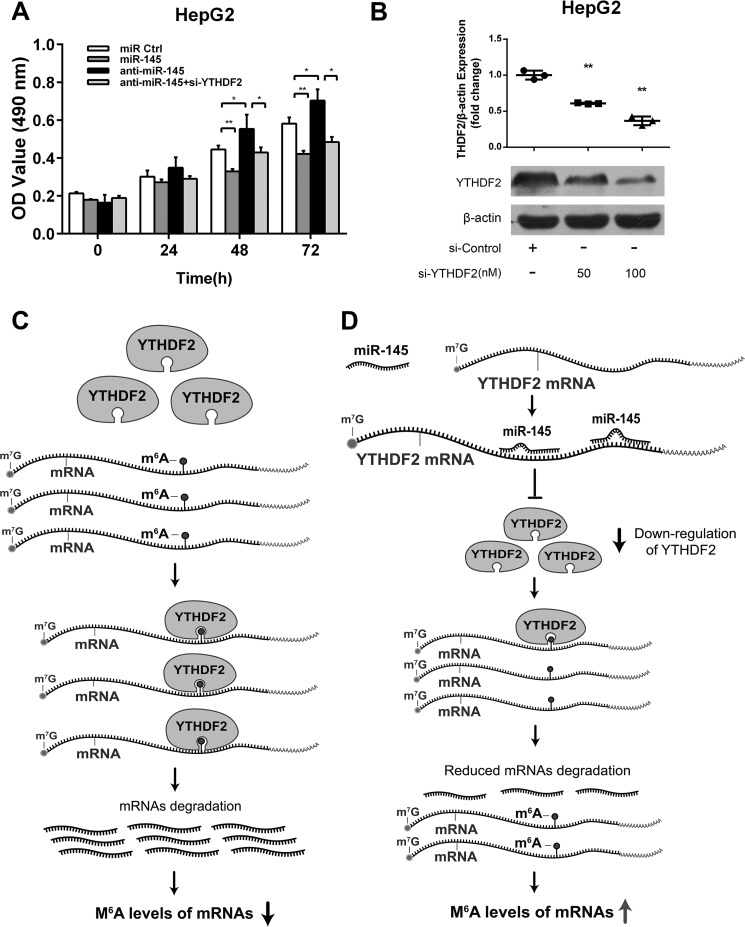

miR-145 Targets YTHDF2 and Suppresses Proliferation of HCC Cells

It has been reported that YTHDF2 knockdown results in the decrease of cell viability in HeLa cells (11). Accordingly, we were concerned about whether miR-145 can affect the proliferation of HCC cells through modulation of YTHDF2. Interestingly, MTT assays indicated that the proliferation of HepG2 cells was decreased when the cells were treated with miR-145, whereas the treatment with anti-miR-145 increased the proliferation. Notably, we observed that YTHDF2 siRNA was able to block the anti-miR-145-enhanced proliferation (Fig. 7A), suggesting that miR-145 suppresses the proliferation of HCC cells through modulating YTHDF2. The interference efficiency of YTHDF2 siRNA was validated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7B). Taken together, we conclude that miR-145 targeting YTHDF2 suppresses proliferation of HCC cells.

FIGURE 7.

miR-145 targets YTHDF2 and suppresses proliferation of HCC cells. A, HepG2 cells were transfected with miRNA control, miR-145, anti-miR-145, and YTHDF2 siRNA. B, interference efficiency of YTHDF2 siRNA was validated by Western blot analysis in HepG2 cells. The effect of miR-145 on cell proliferation was determined by MTT assays. Statistically significant differences are indicated: **, p < 0.01; Student's t test. C, a sketch of the mechanism by which YTHDF2 regulates m6A levels of mRNAs. D, a model shows that miR-145 increases m6A levels of mRNAs through down-regulating YTHDF2.

Discussion

Growing evidence shows that the modification of RNAs is a prevalent feature of mammalian cells and likely plays a role in development and disease (34), in which m6A modification functions mostly through regulating mRNA splicing, export, and stability (35, 36). The modification of m6A needs various functional proteins and enzymes, such as the methylases mettl3/mettl14 and demethylases FTO/ALKBH5 and so on (5, 7, 37). YTHDF2 is an m6A reader protein that has important biological functions in modulation of mRNA m6A (38). However, the regulatory mechanism of YTHDF2 is still unclear. In this study we investigated the post-transcriptional regulation of YTHDF2 in HepG2 cells.

YTHDF2 selectively recognizes mRNA m6A in the regulation of mRNA stability; the degradation of mRNAs can result in the decrease of m6A levels (11). Moreover, it has been reported that YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex, which is recruited to m6A-containing RNAs through a direct interaction between the N-terminal region of YTHDF2 (13). It has been reported that miRNA is a kind of vital bioactive molecule inducing post-transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotic cells (39). Accordingly, we demonstrated the regulation mechanism of YTHDF2 at the post-transcriptional level. IHC staining showed that YTHDF2 was closely associated with the malignance of HCC. It implied that YTHDF2 played a crucial role in the development of liver cancer. Moreover, bioinformatics analysis and Western blot analysis showed that miR-145 could target the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA. Interestingly, the expression levels of miR-145 were negatively correlated with those of YTHDF2 in clinical HCC tissues, suggesting that miR-145 may be able to target the 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA. We then validated that by experiments. Furthermore, we found that miR-145 suppressed the expression of YTHDF2 at the levels of mRNA and protein in HepG2 cells. It has been reported that YTHDF2 can modulate mRNA m6A levels by recognizing m6A sites, leading to mRNA degradation, and the degradation of mRNAs can result in the decrease of m6A levels (11, 13). In our study dot blot assays and immunofluorescence staining showed that miR-145 was able to increase the levels of m6A through down-regulating YTHDF2 in HCC cells, supporting that miR-145 is capable of down-regulating YTHDF2 in HepG2 cells. YTHDF1 was also demonstrated as a selective binding m6A site reader protein. YTHDF1 can regulate mRNA translation efficiency by recognizing mRNA m6A (12). However, we failed to observe the effect of YTHDF1 on levels of m6A in HCC cells.

It has been reported that miR-145 can modulate many biological functions through targeting different genes (40–42), suggesting that the target genes of miR-145 may have synergistic effects in modulation of mRNA m6A modification. Up to now the role of m6A in cancers has not been well documented. In this study we observed that miR-145 could increase the mRNA m6A level in HepG2 cells. In addition, we also showed that miR-145 could increase mRNA m6A levels in immortalized normal liver cell line LO2 and breast cancer cell line MCF-7 (data not shown). Functionally, we found that miR-145 could suppress the proliferation of HepG2 cells. It is reported that miR-145 can induce apoptosis of HCC cells (43). It suggests that the miR-145-increased methylated mRNAs may be also involved in the process of cell apoptosis. Our finding suggests that miR-145 can be a promising therapeutic agent to suppress liver cancer.

Normally, YTHDF2 can recognize mRNA m6A sites as mediating mRNA degradation, which results in the decrease of m6A levels (Fig. 7C). In this study we present a model that miR-145 modulates m6A reader protein YTHDF2 through targeting its mRNA 3′-UTR, leading to the increase of mRNA methylation in HCC cells (Fig. 7D). Thus, our finding provides new insights into the mechanism of YTHDF2 mediated by miR-145 in liver cancer.

Experimental Procedures

Patient Samples

Thirty clinical HCC tissues (n = 30) used in this study were attained from Tianjin First Central Hospital (Tianjin, China) after surgical resection. Written consents approving the use of their tissues for research purposes after the operation were obtained from the patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institute Research Ethics Committee at Nankai University (Tianjin, China).

Immunohistochemistry Staining

The HCC tissue and normal liver tissue microarrays were obtained from the Xi'an Aomei Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Xi'an, China). These microarrays were composed of 188 HCC tissues. IHC staining was performed using rabbit anti-YTHDF2 antibody as described previously (44).

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Human HCC cell line HepG2 was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco). HepG2 cells were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Human embryonic kidney cell line 293T was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as described previously(45).

Isolation of Total RNA, Reverse-transcribed RNA, and Quantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells (or tumor tissues) using RNAiso Plus (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China). The total extraction was treated with DNase I (Sigma). First-strand cDNA was synthesized as described previously (46). To test the expression of miR-145, total RNA was polyadenylated by poly(A) polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX) as described previously (46). Reverse transcription was performed using poly(A)-tailed total RNA and reverse transcription primer with ImPro-II reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's direction. qRT-PCR was performed by a Bio-Rad sequence detection system according to the manufacturer's protocol using double-stranded DNA-specific Fast Start Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche Applied Science). Relative transcriptional levels were examined by the comparative Ct method using 2−ΔΔCt (47). GAPDH was used as a loading control. U6 was used as a loading control to normalize miR-145 levels. The primers used were as follows: YTHDF2 forward, 5′-TAGCCAACTGCGACACATTC-3′; reverse, 5′-CACGACCTTGACGTTCCTTT-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-AACGGATTTGGTCGTATTG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGAAGATGGTGATGGGATT-3′; miR-145 forward, 5′-GTCCAGTTTTCCCAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAA-3′; U6 forward, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′; reverse, 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′; SON forward, 5′-TGACAGATTTGGATAAGGCTCA-3′, reverse, 5′-GCTCCTCCTGACTTTTTAGCAA-3′, CREBBP forward, 5′-CTCAGCTGTGACCTCATGGA-3′; reverse, 5′-AGGTCGTAGTCCTCGCACAC-3′.

Plasmid Construction

YTHDF2 was cloned into vector pcDNA 3.1 (BamHI, XhoI) (forward primer, 5′-CGTACGGATCCATGGATTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGATGTCGGCCAGCAGCC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CGATGCTCGAGTCATTTCCCACGACCTTGACG-3′). YTHDF1 was cloned into vector pcDNA 3.1 (EcoRI, XhoI) (forward primer, 5′-CGTACGAATTCATGGATTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGATGTCGGCCACCAGCG-3′; reverse primer, 5′- CCATACTCGAGTCATTGTTTGTTTCGACTCTGCC-3′). The fragment containing the target sites of miR-145 in 3′-UTR of YTHDF2 mRNA was cloned into pGL3-control vector (Promega) immediately downstream of the stop codon of the luciferase gene to generate pGL3-YTHDF2-WT. Site-directed mutants of the miR-145 target in pGL3-YTHDF2 3′-UTR were named pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1 (containing a substitution of 8 nucleotides in sites 2401–2408), pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 2 (containing a substitution of 8 nucleotides in sites 2699–2706), and pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1 + 2 (containing a substitution of 8 nucleotides in both sites both 2401–2408 and 2699–2706). The primers used in this study for construction were as follows: pGL3-YTHDF2-WT (forward, 5′GCATATCCTA-3′; reverse, 5′-GGGGGCCGGCCACTGTTC TCAGCTTTGAA-3′), pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 1 (forward, 5′-AAAAGACATAGGACTTCCAGTTGGAATGAAAAAAAAAAGA-3′; reverse, 5′-TCTTTTTTTTTTCATTCCAACTGGAAGTCCTATGTCTTTT-3′), pGL3-YTHDF2-mut 2 (forward, 5′-TGATTTTATCCTTCCGCCAGTTGGGAACATTTTTATGAAG-3′; reverse, 3′CTTCATAAAAATGTTCCCAACTGGCGGAAGGATAAAATC-5′.

Cell Transfection

The cells were cultured in 6-well or 24-well plates for 24 h and then were transfected with plasmids, miRNAs or siRNAs. All transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. YTHDF2 siRNA oligonucleotides, miR-145 (or anti-miR-145), and miRNA control (miR Ctrl) were synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). The siRNA duplexes sequences used were as follows: YTHDF2 siRNA, (5′-TTGGCTATTGGGAACGTCCTT-3′), YTHDF1 siRNA (5′-CCGCGTCTAGT TGTTCATGAA3′).

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assays

Luciferase reporter gene assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were plated into 24-well plates (about 3 × 104 cells/well). After 24 h, the cells were co-transfected with the pRL-TK plasmid (Promega), which is used for internal normalization and various constructs containing the seed sequence or mutant seed sequence of YTHDF2 mRNA 3′-UTR. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (48). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-YTHDF2 polyclonal antibody (Proteintech), mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma). All experiments were repeated three times. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software. Quantitative measurements of protein expression levels reported here represent the average of at least three independent biological replicates.

Analysis of m6A Levels Using Dot Blot Assays

m6A levels were analyzed according to protocols reported before (49). Briefly, total RNAs were isolated from transiently transfected cells with RNAiso Plus (Takara Biotechnology). The mRNA was extracted using PolyATtract® mRNA Isolation Systems (Promega). The mRNA concentration was measured by NanoDrop. Isolated mRNA was first denatured by heating at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by chilling on ice directly. The isolated mRNAs were spotted on an Amersham Biosciences Hybond-N+ membrane optimized for nucleic acid transfer (GE Healthcare). Then, the mRNAs were UV cross-linked in a Ultraviolet Crosslinker (Ultra-Violet Products, Cambridge, UK), the membrane was washed by 1× PBST buffer (PBS-Tween), blocked with 5% of nonfat milk in PBST, and incubated with anti-m6A antibody (1: 2,000; Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany) overnight at 4 °C. After incubating with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody, the membrane was visualized by Immobilon Western Chemilum HRP Substrate (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). To ensure an equal amount of mRNA was spotted on the membrane, the same blot was stained with 0.02% methylene blue in 0.3 m sodium acetate (pH 5.2) (6).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells were grown on acid-treated glass coverslips. Treated cells were fixed with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min. After washing 3 times with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS, the samples were blocked in PBS containing 3% BSA for 1 h. Cells were incubated with anti-m6A antibody (Synaptic Systems) for 2 h at room temperature. After being washed, the cells were incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (Rockland) and DAPI. After washing, slides were mounted with glycerol and observed under an upright fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager Z1) with all acquisition settings kept constant for all images. Images were analyzed using Image J software.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assays

Cell proliferation was determined by MTT (Sigma) assay as described previously (50).

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated three times. Statistical significance was assessed by comparing mean values (±S.D.) using a Student's t test for independent groups and was assumed for * (p < 0.05) and ** (p < 0.01); NS, not significant (51). Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between the levels of miR-145 and YTHDF2 mRNA in HCC tissues.

Author Contributions

X. Z., L. Y., and Y. Li conceived the projects, designed the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. X. Z. and Z. Y. designed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. Z. Y., J. L., G. F., and S. G. performed the experiments. W. Y. and S. Z. analyzed the experiments shown in all of the figures. Y. X. provided technical assistance. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (81272218, 81372186, 31470756), the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB553703), and Tianjin Natural Scientific Foundation (14JCZDJC32800). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- m6A

- N6-methyladenosine

- FTO

- fat mass and obesity-associated protein

- YTHDF1

- YTH domain family 1

- miRNA

- microRNA

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- SON

- SON DNA-binding protein

- CREBBP

- CREB-binding protein

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time-PCR

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

References

- 1. Chandola U., Das R., and Panda B. (2015) Role of the N6-methyladenosine RNA mark in gene regulation and its implications on development and disease. Brief. Funct. Genomics 14, 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hastings M. H. (2013) m(6)A mRNA methylation: a new circadian pacesetter. Cell 155, 740–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sibbritt T., Patel H. R., and Preiss T. (2013) Mapping and significance of the mRNA methylome. Wiley interdiscip. Rev. RNA 4, 397–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyer K. D., Saletore Y., Zumbo P., Elemento O., Mason C. E., and Jaffrey S. R. (2012) Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ping X. L., Sun B. F., Wang L., Xiao W., Yang X., Wang W. J., Adhikari S., Shi Y., Lv Y., Chen Y. S., Zhao X., Li A., Yang Y., Dahal U., Lou X. M., et al. (2014) Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 24, 177–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao X., Yang Y., Sun B. F., Shi Y., Yang X., Xiao W., Hao Y. J., Ping X. L., Chen Y. S., Wang W. J., Jin K. X., Wang X., Huang C. M., Fu Y., Ge X. M., et al. (2014) FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 24, 1403–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zheng G., Dahl J. A., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C. M., Li C. J., Vågbø C. B., Shi Y., Wang W. L., Song S. H., Lu Z., Bosmans R. P., Dai Q., Hao Y. J., Yang X., et al. (2013) ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 49, 18–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Niu Y., Zhao X., Wu Y. S., Li M. M., Wang X. J., and Yang Y. G. (2013) N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: an old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 11, 8–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ben-Haim M. S., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., and Rechavi G. (2015) FTO: linking m6A demethylation to adipogenesis. Cell Res. 25, 3–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Todorova T., Bock F. J., and Chang P. (2015) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-13 and RNA regulation in immunity and cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 21, 373–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G. C., Yue Y., Han D., Fu Y., Parisien M., Dai Q., Jia G., Ren B., Pan T., and He C. (2014) N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang X., Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., Lu Z., Han D., Ma H., Weng X., Chen K., Shi H., and He C. (2015) N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Du H., Zhao Y., He J., Zhang Y., Xi H., Liu M., Ma J., and Wu L. (2016) YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 7, 12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cardelli M., Marchegiani F., Cavallone L., Olivieri F., Giovagnetti S., Mugianesi E., Moresi R., Lisa R., and Franceschi C. (2006) A polymorphism of the YTHDF2 gene (1p35) located in an Alu-rich genomic domain is associated with human longevity. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 547–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soifer H. S., Rossi J. J., and Saetrom P. (2007) MicroRNAs in disease and potential therapeutic applications. Mol. Ther. 15, 2070–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finnegan E. F., and Pasquinelli A. E. (2013) MicroRNA biogenesis: regulating the regulators. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48, 51–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gurtan A. M., and Sharp P. A. (2013) The role of miRNAs in regulating gene expression networks. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 3582–3600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gregory R. I., Chendrimada T. P., and Shiekhattar R. (2006) MicroRNA biogenesis: isolation and characterization of the microprocessor complex. Methods Mol. Biol. 342, 33–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jinek M., and Doudna J. A. (2009) A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature 457, 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caruso P., Dempsie Y., Stevens H. C., McDonald R. A., Long L., Lu R., White K., Mair K. M., McClure J. D., Southwood M., Upton P., Xin M., van Rooij E., Olson E. N., Morrell N. W., MacLean M. R., and Baker A. H. (2012) A role for miR-145 in pulmonary arterial hypertension: evidence from mouse models and patient samples. Circ. Res. 111, 290–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Y. S., Li S. H., Guo J., Mihic A., Wu J., Sun L., Davis K., Weisel R. D., and Li R. K. (2014) Role of miR-145 in cardiac myofibroblast differentiation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 66, 94–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ji L. Y., Jiang D. Q., and Dong N. N. (2013) The role of miR-145 in microvasculature. Pharmazie 68, 387–391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu H., Xiao Z., Wang K., Liu W., and Hao Q. (2013) miR-145 is downregulated in human ovarian cancer and modulates cell growth and invasion by targeting p70S6K1 and MUC1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 441, 693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Z., Zhang X., Yang Z., Du H., Wu Z., Gong J., Yan J., and Zheng Q. (2012) miR-145 regulates PAK4 via the MAPK pathway and exhibits an antitumor effect in human colon cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 427, 444–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eades G., Wolfson B., Zhang Y., Li Q., Yao Y., and Zhou Q. (2015) lincRNA-RoR and miR-145 regulate invasion in triple-negative breast cancer via targeting ARF6. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 330–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ozen M., Karatas O. F., Gulluoglu S., Bayrak O. F., Sevli S., Guzel E., Ekici I. D., Caskurlu T., Solak M., Creighton C. J., and Ittmann M. (2015) Overexpression of miR-145–5p inhibits proliferation of prostate cancer cells and reduces SOX2 expression. Cancer Invest. 33, 251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu R., Ji Z., Li X., Zhai Q., Zhao C., Jiang Z., Zhang S., Nie L., and Yu Z. (2014) miR-145 functions as tumor suppressor and targets two oncogenes, ANGPT2 and NEDD9, in renal cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 140, 387–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang F., Xia J., Wang N., and Zong H. (2013) miR-145 inhibits proliferation and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in part by targeting c-Myc. Onkologie 36, 754–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang G., Zhu S., Gu Y., Chen Q., Liu X., and Fu H. (2015) MicroRNA-145 and MicroRNA-133a inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion, while promoted apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via targeting FSCN1. Digest. Dis. Sci. 60, 3044–3052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ding W., Tan H., Zhao C., Li X., Li Z., Jiang C., Zhang Y., and Wang L. (2016) miR-145 suppresses cell proliferation and motility by inhibiting ROCK1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 37, 6255–6260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y., Hu C., Cheng J., Chen B., Ke Q., Lv Z., Wu J., and Zhou Y. (2014) MicroRNA-145 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting IRS1 and its downstream Akt signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 446, 1255–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu H., Liu Y., Liu W., Zhang W., and Xu J. (2015) EZH2-mediated loss of miR-622 determines CXCR4 activation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 6, 8494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saletore Y., Chen-Kiang S., and Mason C. E. (2013) Novel RNA regulatory mechanisms revealed in the epitranscriptome. RNA Biol. 10, 342–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pan T. (2013) N6-methyl-adenosine modification in messenger and long non-coding RNA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li S., and Mason C. E. (2014) The pivotal regulatory landscape of RNA modifications. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 15, 127–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen J., Zhou X., Wu W., Wang X., and Wang Y. (2015) FTO-dependent function of N6-methyladenosine is involved in the hepatoprotective effects of betaine on adolescent mice. J. Physiol. Biochem. 71, 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou J., Wan J., Gao X., Zhang X., Jaffrey S. R., and Qian S. B. (2015) Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature 526, 591–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang J.-S., and Lai E. C. (2011) Alternative miRNA biogenesis pathways and the interpretation of core miRNA pathway mutants. Mol. Cell 43, 892–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chiyomaru T., Tatarano S., Kawakami K., Enokida H., Yoshino H., Nohata N., Fuse M., Seki N., and Nakagawa M. (2011) SWAP70, actin-binding protein, function as an oncogene targeting tumor-suppressive miR-145 in prostate cancer. The Prostate 71, 1559–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dong R., Liu X., Zhang Q., Jiang Z., Li Y., Wei Y., Li Y., Yang Q., Liu J., Wei J. J., Shao C., Liu Z., and Kong B. (2014) miR-145 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by targeting metadherin in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Oncotarget 5, 10816–10829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dynoodt P., Mestdagh P., Van Peer G., Vandesompele J., Goossens K., Peelman L. J., Geusens B., Speeckaert R. M., Lambert J. L., and Van Gele M. J. (2013) Identification of miR-145 as a key regulator of the pigmentary process. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Law P. T., Ching A. K., Chan A. W., Wong Q. W., Wong C. K., To K. F., and Wong N. (2012) miR-145 modulates multiple components of the insulin-like growth factor pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 33, 1134–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu S., Li L., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Zhao Y., You X., Lin Z., Zhang X., and Ye L. (2012) The oncoprotein HBXIP uses two pathways to up-regulate S100A4 in promotion of growth and migration of breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30228–30239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang S., Shan C., Cui W., You X., Du Y., Kong G., Gao F., Ye L., and Zhang X. (2013) Hepatitis B virus X protein protects hepatoma and hepatic cells from complement-dependent cytotoxicity by up-regulation of CD46. FEBS Lett. 587, 645–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shan C., Zhang S., Cui W., You X., Kong G., Du Y., Qiu L., Ye L., and Zhang X. (2011) Hepatitis B virus X protein activates CD59 involving DNA binding and let-7i in protection of hepatoma and hepatic cells from complement attack. Carcinogenesis 32, 1190–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. You X., Liu F., Zhang T., Li Y., Ye L., and Zhang X. (2013) Hepatitis B virus X protein upregulates oncogene Rab18 to result in the dysregulation of lipogenesis and proliferation of hepatoma cells. Carcinogenesis 34, 1644–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang T., Zhang J., You X., Liu Q., Du Y., Gao Y., Shan C., Kong G., Wang Y., Yang X., Ye L., and Zhang X. (2012) Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) modulates oncogene YAP via CREB to promote growth of hepatoma cells. Hepatology 56, 2051–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jia G., Fu Y., Zhao X., Dai Q., Zheng G., Yang Y., Yi C., Lindahl T., Pan T., Yang Y. G., and He C. (2011) N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 885–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shan C., Xu F., Zhang S., You J., You X., Qiu L., Zheng J., Ye L., and Zhang X. (2010) Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes liver cell proliferation via a positive cascade loop involving arachidonic acid metabolism and p-ERK1/2. Cell Res. 20, 563–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Y., Zhao Y., Li H., Li Y., Cai X., Shen Y., Shi H., Li L., Liu Q., Zhang X., and Ye L. (2013) The nuclear import of oncoprotein hepatitis b x-interacting protein depends on interacting with c-Fos and phosphorylation of both proteins in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 18961–18974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]