Abstract

Sphingolipids are a diverse class of essential cellular lipids that function as structural membrane components and as signaling molecules. Cells acquire sphingolipids by both de novo biosynthesis and recycling of exogenous sphingolipids. The individual importance of these pathways for the generation of essential sphingolipids in differentiated cells is not well understood. To investigate the requirement for de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in adipocytes, a cell type with highly regulated lipid metabolism, we generated mice with an adipocyte-specific deletion of Sptlc1. Sptlc1 is an obligate subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase, the enzyme responsible for the first and rate-limiting step of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis. These mice, which initially developed adipose tissue, exhibited a striking age-dependent loss of adipose tissue accompanied by evidence of adipocyte death, increased macrophage infiltration, and tissue fibrosis. Adipocyte differentiation was not affected by the Sptlc1 deletion. The mice also had elevated fasting blood glucose, fatty liver, and insulin resistance. Collectively, these data indicate that de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis is required for adipocyte cell viability and normal metabolic function and that reduced de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis within adipocytes is associated with adipocyte death, adipose tissue remodeling, and metabolic dysfunction.

Keywords: adipocyte, inflammation, lipodystrophy, serine palmitoyltransferase, sphingolipid

Introduction

Sphingolipids are a diverse family of cellular lipids that carry out essential functions both as membrane components and as signaling molecules (1). Within plasma membranes, the complex sphingolipids, sphingomyelin and the glycosphingolipids, are localized in rafts and caveolae, which are membrane domain structures involved in cellular transport and signal transduction. Sphingolipid metabolites, sphingosine, sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P),3 and ceramide, are bioactive and alter cell activity through interaction with intracellular targets and cell-surface receptors.

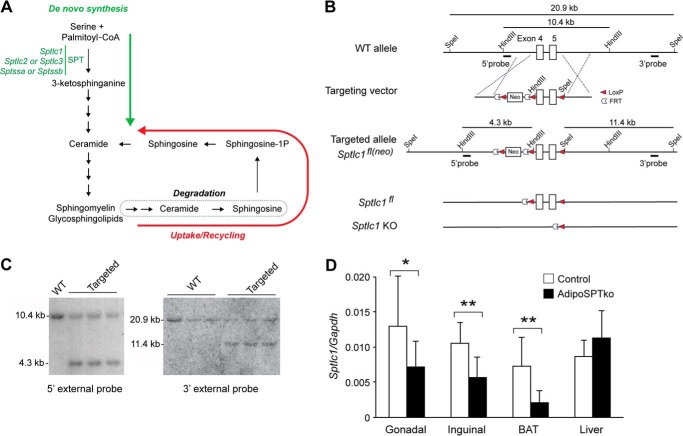

Cells acquire sphingolipids intrinsically by de novo biosynthesis and extrinsically by uptake and recycling of exogenous sphingolipids (Fig. 1A) (1). The de novo biosynthesis of sphingolipids is initiated by the endoplasmic reticulum-localized enzyme serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) through the condensation of serine and fatty acid CoA to yield 3-ketosphinganine, the first step in the biosynthesis of sphingoid bases (Fig. 1A). A sequence of three additional reactions produces ceramide, which serves as the membrane anchor for plasma membrane sphingolipids, sphingomyelin, and glycosphingolipids. Extracellular sphingolipids, which are carried by lipoproteins (VLDL, LDL, and HDL) and serum albumin, can be taken up by cells and catabolized in lysosomes to generate sphingosine (2). Degradation of sphingolipids may also occur extracellularly, with subsequent cellular uptake of sphingosine (3, 4). Intracellularly, through the formation of S1P and its subsequent dephosphorylation, the sphingosine backbone can be recycled for the biosynthesis of ceramide and other sphingolipids. The relative importance of the processes by which cells acquire sphingolipids in vivo is not well understood.

FIGURE 1.

Generation of adipoSPTko mice. A, schematic of the sphingolipid metabolic pathway. The de novo biosynthesis portion is indicated by the green arrow. The uptake/recycling portion is indicated by the red arrow. B, schematic representation of the Sptlc1 targeting strategy. The structures of the WT Sptlc1 locus, the targeting vector, the Sptlc1 targeted allele (Sptlc1fl(neo)), the Sptlc1fl allele, and the Sptlc1 knock-out (KO) allele are shown. The locations of the 5′- and 3′-flanking probes are shown, along with the sizes of the HindIII and SpeI restriction digest fragments. C, Southern blotting analysis of HindIII- (left) and SpeI (right)-digested genomic DNA from embryonic stem cells hybridized with the indicated probe, showing correctly targeted clones (Targeted) and non-targeted clones (WT). D, relative mRNA expression, normalized to Gapdh mRNA expression, for Sptlc1 was determined by RT-qPCR in liver, BAT, and inguinal fat of 4–5-week-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice. Data represent means ± S.D. Student's t test, n = 9 for each genotype; *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Adipocytes employ highly regulated lipid metabolic pathways to carry out their unique functions in the regulation of systemic metabolism (5). These pathways include de novo fatty acid biosynthesis, triglyceride storage and hydrolysis, and fatty acid oxidation. Elevated levels of sphingolipids in adipose tissue have been generally linked to metabolic dysfunction, obesity, and diabetes (5–8). However, the function of the de novo biosynthesis of sphingolipids in normal adipocyte biology is unknown.

To directly identify a role for de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in adipose tissue physiology and metabolism, we generated a mouse model in which SPT was knocked out specifically in adipocytes. Mice with adipocyte-specific deletion of SPT (adipoSPTko) exhibited age-dependent loss of adipose tissue mass. The adipoSPTko adipose tissue displayed evidence of adipocyte death, macrophage infiltration, and fibrosis. Furthermore, the adipoSPTko mice had lipid accumulation in the liver, as well as impaired glucose removal and insulin resistance. These results demonstrate that the de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway is required for adipocyte survival and normal metabolic function.

Results

Generation of adipoSPTko Mice

The SPT holoenzyme is composed of two large subunits, encoded by Sptlc1 and either Sptlc2 or -3, and one small subunit, encoded by either Sptssa or Sptssb (1, 9). To ensure the cellular abrogation of SPT activity without the possibility of substitution by redundant subunits, mice were generated carrying a floxed Sptlc1 allele (Sptlc1fl). A schematic of the targeting vector depicting the homology arms, the Sptlc1 exons 4 and 5, the LoxP and FLP recombinase target (FRT) sequences, and the neomycin gene is shown in Fig. 1B. After gene targeting (Fig. 1, B and C) and generation of mice carrying the targeted Sptlc1fl(neo) allele, the neomycin gene flanked with FRT sites was removed by crossing these mice with FLP recombinase transgenic mice (10), yielding mice with the Sptlc1fl allele (Fig. 1B).

Through breeding Sptlc1fl mice with mice carrying the EIIA-Cre transgene (11), exons 4 and 5 of Sptlc1 were deleted in the germ line. When mice heterozygous for the deletion were interbred, no viable mice homozygous for the deletion were obtained from a total of 92 offspring (35 Sptlc1fl/fl; 57 Sptlc1fl/−; 0 Sptlc1−/−), indicative of embryonic lethality that was demonstrated previously by the global deletion of SPT (12).

To generate adipocyte-specific Sptlc1-deficient mice (adipoSPTko), mice carrying the Cre gene under the control of the Adipoq promotor (13) were used to generate Sptlc1fl/fl mice expressing the Cre recombinase in adipocytes. Levels of Sptlc1 mRNA were significantly reduced in interscapular brown adipose tissue (BAT) and inguinal fat of adipoSPTko mice compared with Sptlc1fl/fl controls (Fig. 1D). However, levels of Sptlc1 mRNA were similar in the liver in the two groups of mice (Fig. 1D), consistent with a specific disruption of Sptlc1 in adipose tissue.

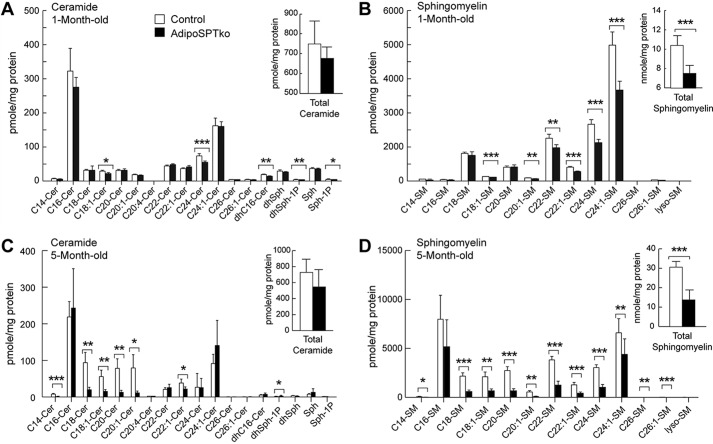

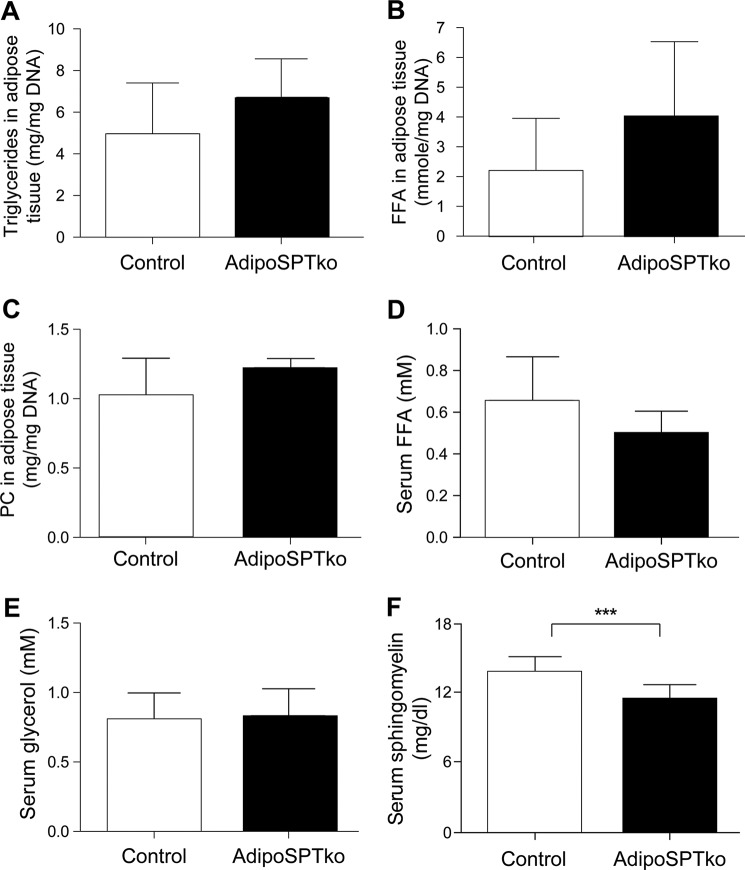

To determine the effect of the Sptlc1 deletion on total sphingolipid amounts in adipose tissue, levels of sphingoid bases, ceramides, and sphingomyelins were determined by mass spectrometry analysis in gonadal adipose tissue from 4-week-old mice. Some individual ceramide species were significantly reduced in adipoSPTko adipose tissue compared with controls (Sptlc1fl/fl), including the de novo species C16-dihydroceramide (Fig. 2A), although the total ceramide level did not show a statistically significant decrease (Fig. 2A, inset). Several sphingomyelin species were significantly reduced in adipoSPTko adipose tissues (Fig. 2B), leading to a statistically significant reduction in total sphingomyelin (Fig. 2B, inset). S1P and dihydroS1P levels were significantly reduced in adipoSPTko adipose tissue compared with controls (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in adipose tissue from 5-month-old adipoSPTko mice, significant reductions in the levels of ceramide species (Fig. 2C), in both specific species (Fig. 2D), and in the total levels of sphingomyelin (Fig. 2D, inset) was present. The levels of triglycerides, free fatty acids, and phosphatidylcholine (normalized to DNA) in gonadal adipose tissue were not significantly different between 4-week-old adipoSPTko mice compared with controls (Fig. 3, A–C).

FIGURE 2.

Sphingolipids in adipose tissue of adipoSPTko mice. Sphingolipid levels were determined by HPLC-tandem MS on lipid extracts from gonadal adipose tissue from 4-week-old (A and B) and 5-month-old (C and D) Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice. A and C, levels of individual ceramide species with different fatty acid chain lengths (Cer), dihydrosphingosine (dhSph), sphingosine (Sph), dihydroS1P, and S1P. Inset, total ceramide. B and D, levels of sphingomyelin (SM) species with different acyl-chain lengths. Inset, total sphingomyelin. Data represent means ± S.D. A and B, n = 7 for each genotype; C and D, n = 5 control and n = 7 adipoSPTko. Student's t test, *, p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

FIGURE 3.

Metabolite levels in adipose tissue and serum of adipoSPTko mice. Triglycerides (A), phosphatidylcholine (PC) (B), and free fatty acid (FFA) (C) levels of gonadal adipose tissue extracts, normalized to DNA, were determined in 4-week-old mice, n = 3 mice per genotype. Free fatty acid (D) and glycerol (E) levels were determined in the serum from 3-month-old mice, n = 5 control, and n = 7 adipoSPTko. F, sphingomyelin levels were determined in serum (4-week-old mice, n = 6 each genotype). Data represent means ± S.D. Student's t test, ***, p < 0.001.

Reduced Adiposity in adipoSPTko Mice

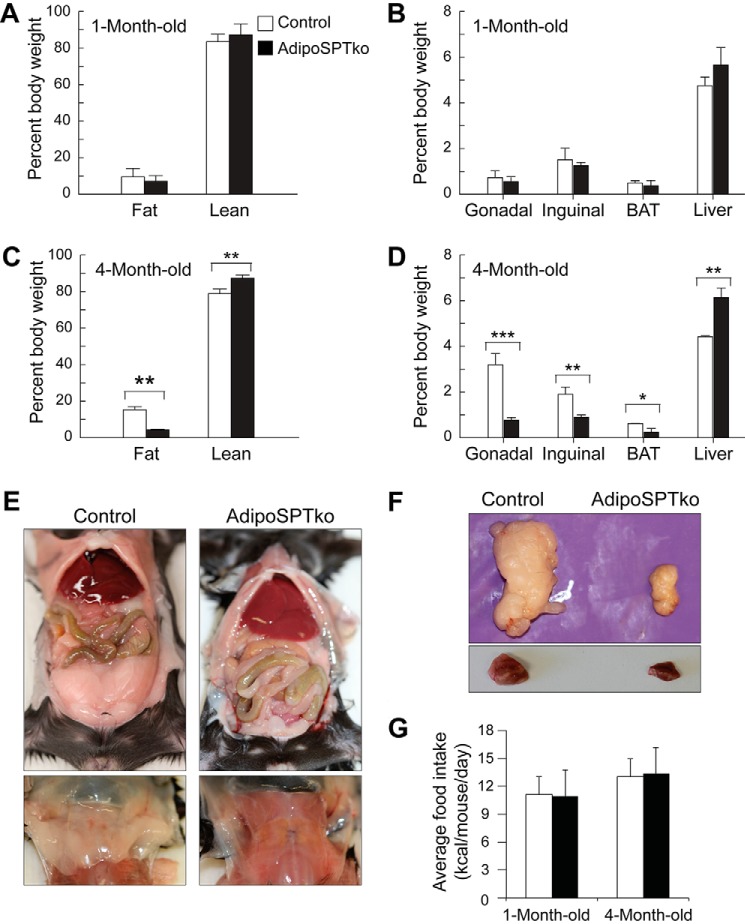

At 1 month of age, adipoSPTko mice were not significantly different from Sptlc1fl/fl controls in their total fat or lean weight when expressed as a percentage of total body weight (Fig. 4A). Likewise, the weights of individual fat depots (gonadal, inguinal, and interscapular BAT), as well as liver, expressed as a percentage of body weight were not significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 4B). However, by 4 months of age, the total body fat and lean weight percentages of the adipoSPTko mice were significantly different from those of controls, with the adipoSPTko mice exhibiting a lower fat and higher lean weight percentage (Fig. 4C). The absolute total lean weights were not significantly different between the adipoSPTko mice and controls (data not shown). In the 4-month-old adipoSPTko mice, the weights of the gonadal, inguinal, and brown fat depots were significantly reduced, whereas liver weight was significantly increased, compared with control mice (Fig. 4, D–F). The food consumption of adipoSPTko mice, both 4-week-old and 4-month-old, was similar to controls (Fig. 4G).

FIGURE 4.

Adipose tissue in adipoSPTko mice. A and C, fat mass and lean mass weight as a percentage of total body weight, measured by EchoMRI, in 1- and 4-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice. B and D, weight of excised gonadal adipose tissue, inguinal adipose tissue, interscapular BAT, and liver in 1- and 4-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice. Data represent means ± S.E. Student's t test, 1-month-old (A): n = 13 control and n = 9 adipoSPTko; 1-month-old (B): n = 9 each genotype; 4-month-old (C and D): n = 7 control and n = 5 adipoSPTko; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. E, photographs of gonadal adipose tissue (top) and interscapular BAT (bottom) before excision from 4-month-old mice. F, photographs of gonadal adipose tissue (top) and interscapular BAT (bottom) after excision from 4-month-old mice. G, average daily food intake. 4-Week-old mice: n = 4 control and n = 5 adipoSPTko; 4-month-old mice: n = 5 control and n = 4 adipoSPTko.

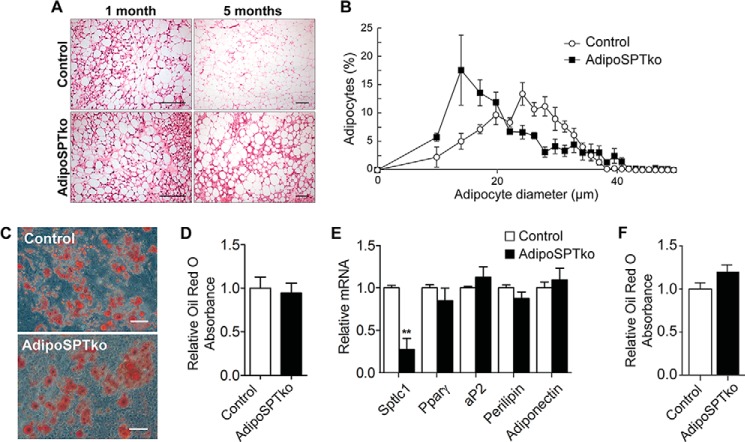

Histologically, the gonadal adipose tissue from 1-month-old adipoSPTko mice was similar to Sptlc1fl/fl control tissue (Fig. 5A, left panels). However, by 5 months of age, adipoSPTko adipose tissue showed an increase in the proportion of smaller adipocytes compared with age-matched control mice (Fig. 5A, right panels). Quantification of the cell size revealed an increase in the fraction of smaller diameter adipocytes in the 5-month-old adipoSPTko mice compared with 5-month-old control mice (Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 5.

Adipocyte development in adipoSPTko mice. A, H&E-stained paraffin sections of gonadal adipose tissue from 1- and 5-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, quantitation of adipocyte size in 5-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice from A. Data represent means ± S.E., n = 4. C–E, primary SVF cells isolated from gonadal adipose tissue of 3-month old control and adipoSPTko mice were differentiated under adipogenic conditions for 8 days. C, representative image of Oil Red O staining. Scale bar, 100 μm. D, quantification of lipid accumulation by Oil Red O recovery. Data represent means ± S.D., n = 3. E, relative mRNA levels for Sptlc1 and adipogenic genes (Pparγ, aP2, perilipin, and adiponectin) were determined by quantitative RT-PCR in differentiated SVF cell cultures. The control value was set to 1. Data represent means ± S.D., Student's t test, n = 3; **, p < 0.01. F, in vitro differentiation of adipocytes in charcoal-treated FBS. Primary SVF cells isolated from gonadal adipose tissue of 1-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice were differentiated under adipogenic conditions using charcoal-treated FBS for 8 days. Quantification of lipid accumulation was by Oil Red O recovery. Data represent means ± S.D., n = 3.

We tested the capability of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells, a source of pre-adipocytes, isolated from gonadal adipose tissue of 3-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice to differentiate to adipocytes in vitro. As assessed by Oil Red O staining, adipocyte differentiation of the control and adipoSPTko pre-adipocytes was similar after 8 days in culture (Fig. 5, C and D). The mRNA expression levels of adipogenic markers (Pparγ, aP2, perilipin, and adiponectin) in control and adipoSPTko adipocyte cultures were also similar. However, as expected, Sptlc1 mRNA levels in adipoSPTko adipocytes were significantly reduced compared with controls (Fig. 5E).

Adipocyte differentiation as assessed by Oil Red O staining was not significantly different between control and adipoSPTko SVF cells when charcoal-treated FBS was substituted for complete FBS in the culture medium (Fig. 5F). Together, these in vivo and in vitro results suggest that adipocyte differentiation in adipoSPTko mice is similar to that in control mice and that the reduced adiposity in adipoSPTko mice is due to the loss of adipose tissue rather than impaired adipocyte differentiation.

Evidence of Adipocyte Death, Macrophage Infiltration, and Tissue Remodeling

We next examined the changes in adipose tissue as the adipoSPTko mice aged to determine the underlying mechanism of the adipose tissue loss. Immunostaining of adipose tissue sections with the macrophage marker Mac-2 revealed an increase in the presence of macrophages in adipoSPTko mice compared with Sptlc1fl/fl control mice (Fig. 6A). Crown-like structures, in which dead adipocytes are surrounded by infiltrating macrophages, were noted around some adipocytes in 2-month-old adipoSPTko mice, while in 5-month-old adipoSPTko mice the majority of adipocytes were completely surrounded by macrophages (Fig. 6A), suggesting that massive cell death had occurred. We also examined adipocytes for the expression of perilipin, which labels lipid droplets of viable adipocytes. Perilipin loss around the lipid droplet has been reported to be another indicator of adipocyte death (14). Immunostaining with perilipin antibodies demonstrated an age-dependent increase in lipid droplets without perilipin coverage in adipoSPTko adipose tissue (Fig. 6B, asterisks), in contrast to the uniform perilipin coverage of adipocyte lipid droplets in control mice.

FIGURE 6.

Adipocyte death, tissue inflammation, and fibrosis in adipoSPTko mice. A, Mac-2 immunostaining in gonadal adipose tissue of 2- and 5-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, perilipin immunostaining in gonadal adipose tissue of 2- and 5-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice. Asterisks denote degenerating perilipin-free adipocytes. Scale bar, 20 μm. C, paraffin sections of gonadal adipose tissue from 2- and 5-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice were stained with Sirius Red to visualize fibrotic accumulation of extracellular collagen. Scale bar, 100 μm. D, transmission electron micrographs of adipocytes from gonadal adipose tissue from 2-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice showing the presence of caveolae (arrows). Scale bar, 0.5 μm. E, quantitation of caveolae on adipocytes from 2-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice. Plasma membrane connected caveolae were counted on transmission electron micrographs images of adipocytes and normalized to plasma membrane surface area. Data represent means ± S.D., n = 3 for each genotype, 5–18 adipocytes per mouse. F, gene expression analysis of immune system and inflammatory genes in gonadal adipose tissue from 5-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice (n = 4). The heat map shows the raw signal values of genes that were significantly increased in adipoSPTko mice, using a cutoff of p < 0.05 and a fold-change of greater than 2 (29/84 genes).

Fibrosis in adipose tissue is often associated with adipocyte death and immune cell infiltration into adipose tissue, and it can be detected by Sirius Red staining (15). AdipoSPTko adipose tissue exhibited substantially more Sirius Red staining than control tissue; Sirius Red staining was especially prominent in the older mice (Fig. 6C).

Ultrastructure analysis of adipose tissue from 2-month-old mice revealed the presence of normal-appearing caveolae on the plasma membrane of adipoSPTko adipocytes. Quantitation of caveolae indicated slightly lower numbers on adipoSPTko adipocytes compared with control adipocytes (p = 0.07) (Fig. 6, D and E).

We also assessed adipose tissue from 5-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice for inflammatory changes using an inflammatory gene expression panel. Compared with control mice, the adipoSPTko mice showed significant changes in mRNA levels for a number of inflammatory genes, including increased mRNA levels of TNF and several macrophage/monocyte chemokines (Ccl2/MCP1, Ccl3/MIP-1α, Ccl4/MIP-1β, Cxcl2/MIP-2, and Ccl22) (Fig. 6F), all of which are factors that are important for macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue (16–18). Collectively, these results suggest that the absence of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in adipoSPTko mice causes adipocytes to die, leading to infiltration of macrophages, inflammation, tissue remodeling, and extensive fibrosis.

Altered Metabolic Profile in adipoSPTko Mice

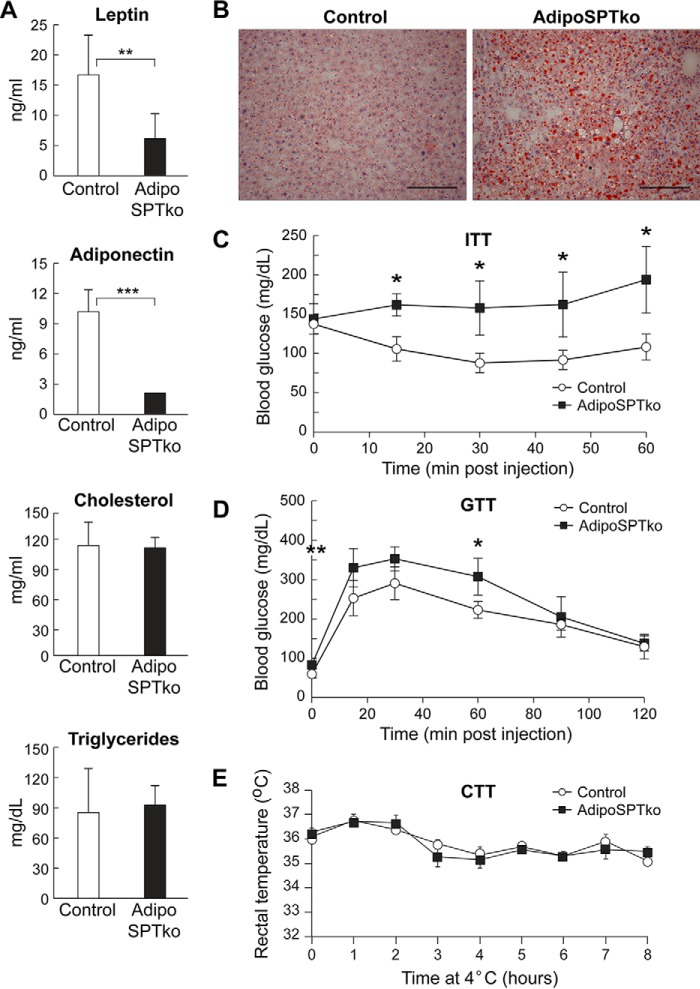

The adipokines leptin and adiponectin were both significantly decreased in the serum of 4-month-old adipoSPTko mice compared with Sptlc1fl/fl controls, whereas the cholesterol, triglyceride, free fatty acid, and glycerol concentrations were not significantly changed (Figs. 3, D and E, and 7A). Serum sphingomyelin levels were slightly decreased in the adipoSPTko mice compared with controls (Fig. 3F). Oil Red O staining of the liver indicated increased lipid accumulation in adipoSPTko mice when compared with control mice (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the liver was utilized as an alternative lipid storage site as a result of the loss of adipose tissue, and it is consistent with the liver enlargement observed in adipoSPTko mice (Fig. 4D) (19). Glucose tolerance tests and insulin tolerance tests demonstrated decreased insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose removal in adipoSPTko mice compared with control mice (Fig. 7, C and D). Cold tolerance testing in which the mice were exposed to 4 °C for 8 h indicated that the adipoSPTko mice could maintain their body temperature similarly to controls (Fig. 7E).

FIGURE 7.

Metabolic profile of adipoSPTko mice. A, leptin, adiponectin, triglycerides, and cholesterol were measured in the serum of 4-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice. Data represent means ± S.D. Student's t test, n = 3; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. B, frozen sections of liver from 5-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice were stained with Oil Red O. Scale bar, 100 μm. C and D, insulin tolerance and glucose tolerance tests (ITT and GTT, respectively) of 3-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice. Data represent means ± S.D. Student's t test, n = 3 for each genotype; *, p < 0.05. E, cold tolerance test (CTT) of 3-month-old control and adipoSPTko mice. Data represent means ± S.D., n = 4 for each genotype.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis has an essential function for adipocyte survival. After deletion of Sptlc1, the sole non-redundant subunit of SPT, in adipocytes, adipose tissue was initially similar to that in control mice as assessed by total mass and histology. The presence of normal stores of adipose tissue in 1-month-old adipoSPTko mice, along with the normal capabilities for in vitro differentiation of stromal vascular precursors from the adipoSPTko mice into adipocytes, suggests that adipocyte development was largely unaffected in adipoSPTko mice. By 4 months of age, adipose tissue depots in adipoSPTko mice were significantly reduced compared with controls. The decreased adipose tissue mass was most likely the result of adipocyte death in adipoSPTko mice, as evidenced by the absence of normal perilipin staining surrounding lipid droplets and by the presence of crown-like structures in adipose tissue of 5-month-old mice. The death and degeneration of adipocytes are believed to provoke macrophage infiltration, which functions in the clearance of lipid and adipocyte debris and allows for extracellular matrix remodeling (14, 16–18). In line with this scenario, extensive fibrosis was observed in adipose tissue of 5-month-old adipoSPTko mice.

Reducing the levels of ceramides generated through the de novo pathway has been associated with improved metabolic function in models of insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity (20). Pharmacological inhibition of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis has led to reduced adipose tissue mass, smaller adipocytes, and improved insulin sensitivity (21). Conversely, increased ceramide levels have been linked to obesity and metabolic dysfunction conditions that have been linked to adipocyte death (22–25). In this light, our results showing that reduction in the de novo biosynthesis of ceramide increases adipocyte death and impairs metabolic function may not have been expected. However, our studies did not examine the pathological conditions of obesity and diabetes, where ceramide in excess may adversely affect metabolic function. Our results do show that under normal homeostatic circumstances, de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis is required for adipocyte survival and proper systemic metabolic function.

The essential requirement for de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in adipocytes contrasts with some other cell types, where the pathway is apparently dispensable. An adult liver-specific Sptlc2 knock-out mouse, which had an almost complete SPT deficiency, exhibited reduced ceramide and sphingomyelin in both liver and plasma, but it displayed no apparent adverse effect on the liver (26). Likewise, deletion of Sptlc2 in macrophages did not alter their polarization, inflammatory capability, or number in mice fed a high-fat diet (27). The requirement for de novo biosynthesis in adipocytes indicates that they are unable to acquire sufficient sphingolipids through alternative uptake and recycling pathways for cell survival. This may indicate that adipocytes have an essential requirement for de novo synthesized sphingolipids because of their unique physiology. Adipocytes must respond rapidly to systemic energy conditions by reduction or expansion in size commensurate with increased lipid storage or lipid mobilization. Changes in adipocyte size can occur rapidly, which may demand the acute increase of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis to maintain the proper lipid composition in the plasma membrane (5). Up to 30% of the plasma membrane surface of adipocytes is composed of caveolae, which are membrane domains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids imparting a “detergent-resistant” characteristic (5, 28). Adipocytes take up and release fatty acids, which are mild detergents, as one of their major functions. Therefore, the detergent-resistant sphingolipid domains may protect the adipocyte membrane from the deleterious effects of exposure to high concentrations of fatty acids during their transport and metabolism, as has been shown for the caveolae themselves (28).

Mice globally lacking sphingomyelin synthase 1 (Sms1) (29) have been shown to have reduced sphingomyelin levels in adipose tissue and a strikingly similar phenotype to the adipoSPTko mice described here in that they exhibit an age-dependent reduction of adipose tissue mass, with evidence of adipocyte cell death. It was inferred that ceramide accumulation, due to the block in conversion to sphingomyelin, was responsible for the phenotype. However, our results indicate that the reduction of sphingolipids, which includes both sphingomyelin and ceramide, yields a similar phenotype. Taken together, the results from the Sms1-null mice and the adipoSPTko mice suggest that the reduction of sphingomyelin may be a potential cause of this shared phenotype.

With their severe adipose tissue loss and insulin resistance, the adipoSPTko mice exhibit a form of lipodystrophy. Genes involved in adipogenesis, lipid metabolism, and caveolae formation have been identified as causing familial lipodystrophies in humans (30). Our findings suggest that conditions that reduce the de novo production of sphingolipids may also be potential causes of congenital lipodystrophies.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse Generation and Procedures

All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institutes of Health, NIDDK.

To generate Sptlc1fl mice, an Sptlc1 gene targeting vector was constructed to flank exons 4 and 5, which encode part of the active site, with LoxP sites 973 bp apart. A short homology (∼2 kb) arm extended 5′ to exon 4 and a long homology arm (∼5.7 kb) was located 3′ to exon 5. The neomycin (neo) gene was present between the short homology arm and exon 4 and was flanked by FRT sequences. A schematic of the targeting vector is shown in Fig. 1B. The targeting vector was linearized and transfected by electroporation into hybrid embryonic stem cells (Ingenious Targeting Laboratory, Ronkonkoma, NY). Following selection with G418, surviving clones were expanded and tested by PCR for identification of the positive clones, which were then confirmed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1C). Confirmed clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 mouse blastocysts to obtain germ line transmission. The generated chimeras and subsequently their offspring were genotyped to determine the presence of the Sptlc1fl(neo) gene. Subsequently, to avoid interference with endogenous gene transcription, the neomycin gene was eliminated in the germ line by crossing the Sptlc1fl(neo) mice with mice expressing FLP recombinase (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Additional genotyping was performed using PCR to confirm the absence of the neomycin gene. The following primers were used for PCR to distinguish the WT Sptlc1 from the Sptlc1fl allele: 5′-GGG TTC TAT GGC ACA TTT GGT AAG-3′ (forward primer), and 5′-CTG TTA CTT CTT GCC AGT GGA C-3′ (reverse primer), which generate products of 350 bp (WT) and 425 bp (Sptlc1fl).

To globally delete the Sptlc1 gene, mice carrying Sptlc1fl were crossed with mice expressing EIIA-Cre (stock no. 003724, The Jackson Laboratory). The recombined Sptlc1 knock-out allele was identified by PCR using 5′-CAGAGCTAATGGAAAGGTGTC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-CTG TTA CTT CTT GCC AGT GGA C-3′ (reverse primer), which generate a product of 315 bp.

To generate adipoSPTko mice, mice carrying Sptlc1fl were crossed with mice expressing adipoq-Cre (13) (stock no. 010803, The Jackson Laboratory). The adipoSPTko mice were Sptlc1fl/fl carrying one adipoq-Cre allele. Controls were littermate Sptlc1fl/fl mice. The Sptlc1fl allele was detected as described above. The adipoq-Cre allele was detected by PCR with the following primers: 5′-GCCTGCATTACCGGTCGATGC-3′ (forward primer), and 5′-CAGGGTGTTATAAGCAATCCC-3′ (reverse primer), which generate a product of ∼500 bp.

RNA Expression Analysis

Total RNA from mouse BAT, gonadal fat, inguinal fat, and liver was purified using the RNeasy lipid tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), total RNA was first digested with DNase I and subsequently reverse-transcribed with the First-strand cDNA Synthesis System for Quantitative RT-PCR (Origene, Rockville, MD) following the manufacturer's instructions. mRNA expression levels were determined using predesigned Assay-on-Demand probes and primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for mouse Sptlc1 (Mm00447343_m1) and Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1). The primers and method used for quantitative RT-qPCR assays to detect mRNAs isolated from adipocyte cultures have been described (31).

For the inflammatory gene expression panel, DNase-treated RNA was reverse-transcribed with RT2 First Strand (Qiagen), and expression was determined by using Mouse Inflammatory Response and Autoimmunity RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays (Qiagen). Expression analysis was performed on an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA).

SVF Cell Isolation and Adipocyte Differentiation

Gonadal adipose tissue from 3-month-old Sptlc1fl/fl control and adipoSPTko mice was minced and subjected to collagenase (1 mg/ml) digestion at 37 °C for 45 min in buffer containing 0.123 m NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.3 mm CaCl2, 5 mm glucose, 100 mm Hepes, and 4% BSA, filtered through a 100-μm nylon screen, and centrifuged at 150 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Cell pellets were washed twice and resuspended in DMEM containing 25 mm glucose, 20% FBS, 20 mm Hepes, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Culture medium was changed daily. For differentiation assays, confluent stromal vascular cells were stimulated with culture medium containing 10% FBS (defined or charcoal-treated; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin supplemented with 0.5 mm isobutylmethylxanthine, 125 μm indomethacin, 5 μm dexamethasone, 20 nm insulin, 1 nm triiodothyronine, and 1 μm rosiglitazone for 48 h and then subsequently cultured in maintenance medium containing 10% FBS, 1 μm rosiglitazone, 20 nm insulin, and 1 nm triiodothyronine. To quantify the extent of adipocyte differentiation, lipid accumulation was determined by staining cells with Oil Red O. The dye was extracted with isopropyl alcohol, and the absorbance was measured at 520 nm.

Histology

Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Liver was embedded in OCT medium, sectioned, and stained with Oil Red O. Gonadal adipose tissue was embedded in paraffin for H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) were dewaxed and rehydrated. After heat-induced epitope retrieval, sections were incubated with anti-Mac-2 (1:100, mouse monoclonal (A3A12), catalog no. ab2785, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or anti-perilipin A (1:1000, rabbit polyclonal, catalog no. ab3526, Abcam) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Immunohistochemical detection was performed with the Mouse on Mouse ImmPRESSTM peroxidase polymer kit (catalog no. MP-2400, Vector Laboratories) for Mac-2 or the ImmPRESSTM Excel anti-Rabbit Ig peroxidase staining kit (catalog no. MP-7601, Vector Laboratories) for perilipin A, strictly following the manufacturer's protocols. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (catalog no. H-3401, Vector Laboratories) and mounted with VectaMount Medium (catalog no. H-5000, Vector Laboratories). Histology and immunohistochemistry slides were examined on a Leica DMLB microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy of adipose tissue samples was performed as described (32). Caveolae were quantitated from transmission electron micrographs using the ImageJ software package (33). Plasma membrane connected caveolae were counted and normalized to plasma membrane surface area, as measured with the free-hand line selection tool.

Adipocyte Size Determination

Adipocyte sizes were obtained from representative bright field digital micrographs of H&E-stained gonadal adipose tissue. Using the ImageJ software package (33), each adipocyte was outlined using the freehand selection tool, the perimeter of each adipocyte calculated with the measure tool, and the diameter was obtained. At least 119 adipocytes were measured per sample.

Metabolic Studies

Body composition was assessed in non-anesthetized mice by EchoMRI 3-in-1 analyzer (EchoMRI, Houston, TX). Concentrations of leptin and adiponectin in serum collected from randomly fed mice were determined using a radioimmunoassay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Serum triglycerides (Pointe Scientific Inc., Canton, MI), free fatty acids (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany), glycerol (BioVision, Milpitas, CA), sphingomyelin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), and cholesterol (Thermo Scientific) levels were measured by colorimetric assays according to the manufacturer's procedures. Blood glucose was measured by using a Glucometer Contour (Ascensia, Basel, Switzerland). Glucose and insulin tolerance tests were performed in mice fasted overnight or randomly fed mice, respectively, as described previously (34). Food intake was measured automatically using Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS, Columbus Instruments Inc., Columbus, OH). For cold tolerance testing, mice were housed individually at 4 °C (with food and water ad libitum, but without bedding). Rectal temperature was measured hourly using a Termalert (Physitemp, Clifton, NJ) rectal probe (35).

Lipid Measurements in Adipose Tissue

Sphingolipids in extracts from gonadal adipose tissue were measured by HPLC-tandem MS by the Lipidomics Core at the Medical University of South Carolina on a Thermo Finnigan (Waltham, MA) TSQ 7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, operating in a multiple reaction monitoring-positive ionization mode as described (36).

Triglyceride and phosphatidylcholine content of gonadal adipose tissue extracts were measured using colorimetric assay kits, and free fatty acids were measured with a fluorometric assay kit (all from Cayman Chemical).

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired Student's t tests were performed to compare results between different groups. p values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

A. A. and R. L. P. conceived the project. A. A., B. A. C., O. G., Y. M., H. Z., X. M., L. X., G. T., B. C. L., M. L. A., T. M. D., and R. L. P. contributed to the design and coordination of experiments. A. A., B. A. C., O. G., Y. M., H. Z., X. M., L. X., G. T., B. C. L., and M. L. A. were directly involved in experimental data acquisition. A. A., B. A. C., O. G., Y. M., H. Z., X. M., L. X., G. T., B. C. L., M. L. A., T. M. D., and R. L. P. contributed to interpretation of the data. A. A. and R. L. P. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Raab for editorial assistance. The Lipidomics Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina, was the recipient of National Institutes of Health Grants P30CA138313 and P20RR017677.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institutes of Health, NIDDK (to R. L. P.) and Grant R21HD08018 (to T. M. D.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- S1P

- sphingosine 1-phosphate

- SPT

- serine palmitoyltransferase

- FRT

- FLP recombinase target

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- SVF

- stromal vascular fraction

- RT-qPCR

- real time quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Merrill A. H., Jr. (2011) Sphingolipid and glycosphingolipid metabolic pathways in the era of sphingolipidomics. Chem. Rev. 111, 6387–6422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nilsson A., and Duan R. D. (2006) Absorption and lipoprotein transport of sphingomyelin. J. Lipid Res. 47, 154–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Y., Kalari S. K., Usatyuk P. V., Gorshkova I., He D., Watkins T., Brindley D. N., Sun C., Bittman R., Garcia J. G., Berdyshev E. V., and Natarajan V. (2007) Intracellular generation of sphingosine 1-phosphate in human lung endothelial cells: role of lipid phosphate phosphatase-1 and sphingosine kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14165–14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kono M., Dreier J. L., Ellis J. M., Allende M. L., Kalkofen D. N., Sanders K. M., Bielawski J., Bielawska A., Hannun Y. A., and Proia R. L. (2006) Neutral ceramidase encoded by the Asah2 gene is essential for the intestinal degradation of sphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7324–7331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rutkowski J. M., Stern J. H., and Scherer P. E. (2015) The cell biology of fat expansion. J. Cell Biol. 208, 501–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turpin S. M., Nicholls H. T., Willmes D. M., Mourier A., Brodesser S., Wunderlich C. M., Mauer J., Xu E., Hammerschmidt P., Brönneke H. S., Trifunovic A., LoSasso G., Wunderlich F. T., Kornfeld J. W., Blüher M., Krönke M., and Brüning J. C. (2014) Obesity-induced CerS6-dependent C16:0 ceramide production promotes weight gain and glucose intolerance. Cell Metab. 20, 678–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Samad F., Badeanlou L., Shah C., and Yang G. (2011) Adipose tissue and ceramide biosynthesis in the pathogenesis of obesity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 721, 67–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chavez J. A., and Summers S. A. (2012) A ceramide-centric view of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 15, 585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Han G., Gupta S. D., Gable K., Niranjanakumari S., Moitra P., Eichler F., Brown R. H. Jr, Harmon J. M., and Dunn T. M. (2009) Identification of small subunits of mammalian serine palmitoyltransferase that confer distinct acyl-CoA substrate specificities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8186–8191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farley F. W., Soriano P., Steffen L. S., and Dymecki S. M. (2000) Widespread recombinase expression using FLPeR (flipper) mice. Genesis 28, 106–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lakso M., Pichel J. G., Gorman J. R., Sauer B., Okamoto Y., Lee E., Alt F. W., and Westphal H. (1996) Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 5860–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hojjati M. R., Li Z., and Jiang X. C. (2005) Serine palmitoyl-CoA transferase (SPT) deficiency and sphingolipid levels in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1737, 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eguchi J., Wang X., Yu S., Kershaw E. E., Chiu P. C., Dushay J., Estall J. L., Klein U., Maratos-Flier E., and Rosen E. D. (2011) Transcriptional control of adipose lipid handling by IRF4. Cell Metab. 13, 249–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cinti S., Mitchell G., Barbatelli G., Murano I., Ceresi E., Faloia E., Wang S., Fortier M., Greenberg A. S., and Obin M. S. (2005) Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J. Lipid Res. 46, 2347–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun K., Tordjman J., Clément K., and Scherer P. E. (2013) Fibrosis and adipose tissue dysfunction. Cell Metab. 18, 470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanda H., Tateya S., Tamori Y., Kotani K., Hiasa K., Kitazawa R., Kitazawa S., Miyachi H., Maeda S., Egashira K., and Kasuga M. (2006) MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1494–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu H., Barnes G. T., Yang Q., Tan G., Yang D., Chou C. J., Sole J., Nichols A., Ross J. S., Tartaglia L. A., and Chen H. (2003) Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1821–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun K., Kusminski C. M., and Scherer P. E. (2011) Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2094–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moitra J., Mason M. M., Olive M., Krylov D., Gavrilova O., Marcus-Samuels B., Feigenbaum L., Lee E., Aoyama T., Eckhaus M., Reitman M. L., and Vinson C. (1998) Life without white fat: a transgenic mouse. Genes Dev. 12, 3168–3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bikman B. T., and Summers S. A. (2011) Ceramides as modulators of cellular and whole-body metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4222–4230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Samad F., Hester K. D., Yang G., Hannun Y. A., and Bielawski J. (2006) Altered adipose and plasma sphingolipid metabolism in obesity: a potential mechanism for cardiovascular and metabolic risk. Diabetes 55, 2579–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blachnio-Zabielska A. U., Koutsari C., Tchkonia T., and Jensen M. D. (2012) Sphingolipid content of human adipose tissue: relationship to adiponectin and insulin resistance. Obesity 20, 2341–2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boon J., Hoy A. J., Stark R., Brown R. D., Meex R. C., Henstridge D. C., Schenk S., Meikle P. J., Horowitz J. F., Kingwell B. A., Bruce C. R., and Watt M. J. (2013) Ceramides contained in LDL are elevated in type 2 diabetes and promote inflammation and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Diabetes 62, 401–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haus J. M., Kashyap S. R., Kasumov T., Zhang R., Kelly K. R., Defronzo R. A., and Kirwan J. P. (2009) Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes 58, 337–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kolak M., Gertow J., Westerbacka J., Summers S. A., Liska J., Franco-Cereceda A., Orešič M., Yki-Järvinen H., Eriksson P., and Fisher R. M. (2012) Expression of ceramide-metabolising enzymes in subcutaneous and intra-abdominal human adipose tissue. Lipids Health Dis. 11, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Z., Li Y., Chakraborty M., Fan Y., Bui H. H., Peake D. A., Kuo M. S., Xiao X., Cao G., and Jiang X. C. (2009) Liver-specific deficiency of serine palmitoyltransferase subunit 2 decreases plasma sphingomyelin and increases apolipoprotein E levels. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27010–27019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Camell C. D., Nguyen K. Y., Jurczak M. J., Christian B. E., Shulman G. I., Shadel G. S., and Dixit V. D. (2015) Macrophage-specific de novo synthesis of ceramide is dispensable for inflammasome-driven inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 29402–29413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meshulam T., Breen M. R., Liu L., Parton R. G., and Pilch P. F. (2011) Caveolins/caveolae protect adipocytes from fatty acid-mediated lipotoxicity. J. Lipid Res. 52, 1526–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yano M., Yamamoto T., Nishimura N., Gotoh T., Watanabe K., Ikeda K., Garan Y., Taguchi R., Node K., Okazaki T., and Oike Y. (2013) Increased oxidative stress impairs adipose tissue function in sphingomyelin synthase 1 null mice. PLoS ONE 8, e61380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patni N., and Garg A. (2015) Congenital generalized lipodystrophies: new insights into metabolic dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 522–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma X., Xu L., Alberobello A. T., Gavrilova O., Bagattin A., Skarulis M., Liu J., Finkel T., and Mueller E. (2015) Celastrol protects against obesity and metabolic dysfunction through activation of a HSF1-PGC1α transcriptional axis. Cell Metab. 22, 695–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alexaki A., Gupta S. D., Majumder S., Kono M., Tuymetova G., Harmon J. M., Dunn T. M., and Proia R. L. (2014) Autophagy regulates sphingolipid levels in the liver. J. Lipid Res. 55, 2521–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., and Eliceiri K. W. (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamashita T., Hashiramoto A., Haluzik M., Mizukami H., Beck S., Norton A., Kono M., Tsuji S., Daniotti J. L., Werth N., Sandhoff R., Sandhoff K., and Proia R. L. (2003) Enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice lacking ganglioside GM3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3445–3449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen M., Chen H., Nguyen A., Gupta D., Wang J., Lai E. W., Pacak K., Gavrilova O., Quon M. J., and Weinstein L. S. (2010) G(s)α deficiency in adipose tissue leads to a lean phenotype with divergent effects on cold tolerance and diet-induced thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 11, 320–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pettus B. J., Bielawski J., Porcelli A. M., Reames D. L., Johnson K. R., Morrow J., Chalfant C. E., Obeid L. M., and Hannun Y. A. (2003) The sphingosine kinase 1/sphingosine 1-phosphate pathway mediates COX-2 induction and PGE2 production in response to TNF-α. FASEB J. 17, 1411–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]