Dear Editor,

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), as the most abundant internal modification with ubiquitous feature in eukaryotic mRNAs, has been connected with many fundamental aspects of RNA metabolism such as translation1,2,3, splicing4,5, stability and decay6. m6A modification is reversible and can be regulated by three groups of molecules commonly referred to as writers, erasers and readers. m6A writers are the components of the multi-complex methyltransferase catalyzing the formation of m6A methylation, among which METTL3, METTL14, WTAP and KIAA1429 are the key ones7,8,9,10,11. FTO and ALKBH5 (both belonging to AlkB family proteins) serve as the erasers of m6A modification12,13. The reader proteins can mediate biological function of the chemical modifications through recognizing and selectively binding to them. Several m6A readers with YTH domain located in the cytoplasmic compartment (YTHDF1, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3) and nuclear compartment (YTHDC1) have been identified and possess differential functions based on their molecular features and cellular localization. Cytoplasmic readers YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 were demonstrated to modulate translation of m6A-modified mRNA and mediate degradation of methylated mRNAs by targeting them to the decay sites, respectively2,6. Our recent study revealed that nuclear reader YTHDC1 regulates m6A-dependent mRNA splicing4. However, the detailed function of cytoplasmic reader YTHDF3 is still unclear. In this study, we show that YTHDF3 promotes translation, thus playing an important role in the initial stages of translation.

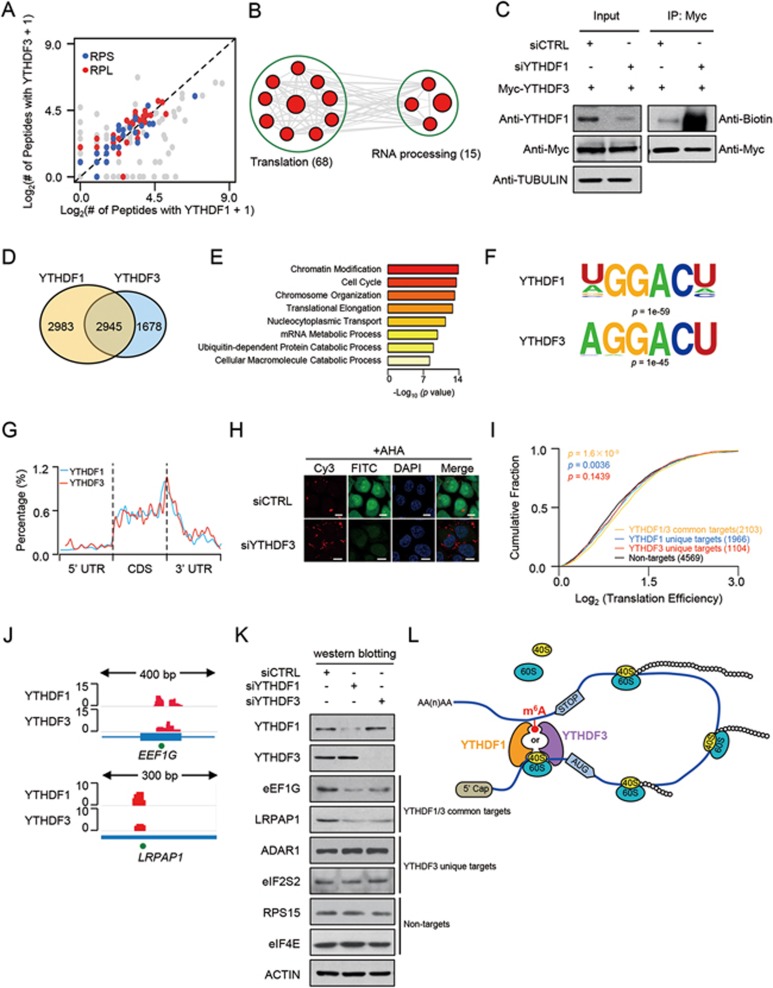

To unveil the potential function of cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3, we searched for their interacting partners by tandem-affinity purification assay using 293T cells expressing SFB-tagged YTHDF3 (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Meanwhile, YTHDF1-binding partners were also explored using the same approach in 293T cells expressing SFB-tagged YTHDF1 (peptide atlas access number PASS00934). A total of 295 and 304 proteins were found to interact with YTHDF3 and YTHDF1, respectively; and among them 152 proteins interacted with both proteins (Figure 1A and Supplementary information, Figure S1A). We performed gene ontology (GO) analysis with DAVID bioinformatics database and found that 68 proteins are enriched in functional pathways related to translation (Figure 1B), including 23 proteins of 40S subunits and 35 proteins of 60S subunits (Figure 1A), which is remarkable as total numbers of protein in eukaryotic 40S and 60S subunits are 33 and 47, respectively. This result implies that YTHDF3 potentially plays a role in translation probably through ribosomal proteins.

Figure 1.

YTHDF3 promotes translation by interacting with ribosomal proteins. (A) Scatter plot of proteins bound to YTHDF1 versus YTHDF3. Enriched 40S and 60S subunit proteins are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. (B) Gene ontology and enrichment analysis of proteins that interact with both YTHDF1 and YTHDF3. 152 proteins were subjected to DAVID GO analysis. An enrichment map was constructed by using Cytoscape with the Enrichment Map plugin. (C) PAR-CLIP of YTHDF3 protein in control- and YTHDF1-depleted HeLa cells transfected with Myc-YTHDF3 plasmid. The pull-down RNA products were labeled with biotin at 3′ end (Biotinylation Kit, Thermo) and then visualized by the Chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module. (D) Venn diagram of the overlapping mRNAs with binding clusters of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 detected by PAR-CLIP-seq. (E) Gene ontology analysis of 2 945 mRNAs bound by both YTHDF1 and YTHDF3. DAVID was used for the GO analysis. The enriched terms were ranked by −log10 (P-value). (F) YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 binding motifs identfied by HOMER from PAR-CLIP clusters. (G) Distribution of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 binding clusters across the length of mRNA transcripts. 5′ UTRs, CDSs and 3 UTRs of mRNAs are individually binned into regions spanning 1% of their total length, and the percentage of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 binding clusters that fall within each bin is determined. (H) Immunofluorescence analysis of nascent protein synthesis in control- and YTHDF3-deficient HeLa cells. FITC (green): newly synthesized protein; CY3 (red): 5′-CY3-labeled siRNAs; DAPI (blue): DNA. Scale bar: 10 μm. Representative images from one of three independent experiments are shown. (I) Cumulative distribution of translation efficiency (ratio of ribosome-bound fragments and mRNA input) among non-targets of both YTHDF1 and YTHDF3, YTHDF1 unique targets, YTHDF3 unique targets and YTHDF1/3 common targets. The p-values are calculated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test. (J) IGV tracks displaying YTHDF1, YTHDF3 binding clusters and m6A peaks within EEF1G and LRPAP1. The green dots at the bottom of the tracks depict the positions of m6A peaks. (K) Protein levels of YTHDF1/3 common targets (EEF1G and LRPAP1), YTHDF3 unique targets (ADAR1 and EIF2S3) and non-targets of both YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 (RPS15 and EIF4E) in YTHDF1 or YTHDF3 knockdown cells detected by western blotting. HeLa cells were transfected with YTHDF1, YTHDF3 or control siRNA. Forty eight hours later, cells were lysed and subjected to western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (L) YTHDF3, in cooperation with YTHDF1, modulates the translation of m6A-modified mRNAs by binding to m6A-modified mRNAs and interacting with proteins of 40S and 60S subunits.

To explore the effect of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 on each other's RNA-binding affinity, we performed PAR-CLIP (photoactivatable ribonucleoside crosslinking and immunoprecipitation) combined with in vitro RNA-end biotin-labeling assay. Intriguingly, YTHDF3 RNA-binding ability was significantly increased upon YTHDF1 knockdown (Figure 1C); and similarly, RNA-binding affinity of YTHDF1 was significantly enhanced when YTHDF3 was knocked down (Supplementary information, Figure S1B), suggesting that YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 negatively affect each other's RNA-binding affinity.

We next verified the interaction of YTHDF3 with ribosomal components using Flag-tagged fusion proteins (Flag-RPL3, Flag-RPLP0, Flag-RPS2, Flag-RPS3 and Flag-RPS15) expressed in 293T cells by immunoprecipitation on cell lysates using anti-FLAG beads. The purified Flag-tagged proteins were incubated with GST-YTHDF3 for GST pull-down assay. We found that YTHDF3 interacts with the ribosomal proteins (Supplementary information, Figure S1C–S1F).

To characterize the RNA species that YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 bind, we performed PAR-CLIP using 4-thiouridine (4SU) to crosslink RNA with protein producing a detectable T-to-C mutation and used PARalyzer software for data analyses to identify the preferred RNA-binding regions of YTHDF3 and YTHDF1. We found both proteins primarily bind to mRNAs (Supplementary information, Figure S2A). About 4 623 mRNA species were identified as potential targets of YTHDF3. Among them, 2 945 transcripts were also bound by YTHDF1 (Figure 1D); these transcripts were subjected to GO term analysis by DAVID. The results showed that mRNA transcripts bound by both proteins are involved in a variety of biological functions including chromatin modification, cell cycle, chromosome organization, translational elongation, etc. (Figure 1E). In addition, YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 have their own unique substrates (Figure 1D).

To identify the region(s) within mRNA transcript that YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 preferentially bind, we mapped the mRNA-binding clusters of both proteins into four non-overlapping transcript regions: 5′ UTR, coding sequence (CDS), 3′ UTR and intron, according to the human reference transcript annotation. The binding clusters of both reader proteins are highly enriched in CDSs and 3′ UTRs (Supplementary information, Figure S2B), which is consistent with m6A peaks14,15.

To define the sequence motif recognized by YTHDF3 and YTHDF1, we analyzed the binding cluster data using HOMER with the parameter for motif length set between 5 and 8. A RGACH (R = G or A; H = A, C or U) motif, coinciding with the m6A consensus motif, was identified from PAR-CLIP samples of YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 (Figure 1F). The YTHDF3- and YTHDF1-binding clusters were also enriched around the stop codon (Figure 1G), resembling the distributive pattern of m6A peaks on mRNA14,15.

The findings that YTHDF3 interacts with translation-related proteins prompted us to validate the biological significance of YTHDF3 in regulation of mRNA translation. We performed an in vivo quantitative assay of nascent protein synthesis where ℒ-azidohomoalaine (AHA), an amino acid analog containing an azido moiety that can be incorporated into proteins during protein synthesis, was used. This modified amino acid can be detected by the Click iT reaction and followed by confocal microscopy. A significant decrease in translation efficiency was observed in YTHDF3 knockdown samples compared with the controls (Figure 1H and Supplementary information, Figure S2C). We next confirmed that the change of nascent protein synthesis was a direct effect of YTHDF3 knockdown as nascent proteins synthesis could be significantly rescued by reconstitution with the wild-type but not m6A-binding defective YTHDF3 (Supplementary information, Figure S2D and S2E).

We further used available ribosome profiling data2 to assess the translation efficiency of mRNA transcripts with or without YTHDF3 binding. Transcripts present (reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) > 1) in both ribosome profiling and mRNA sequencing samples were analyzed in parallel. These transcripts were then categorized into four groups: non-targets for both of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3, YTHDF1 unique targets, YTHDF3 unique targets and YTHDF1/3 common targets based on their PAR-CLIP data. Compared with the non-targets, YTHDF1/3 common targets, but not YTHDF3 unique targets (P = 0.1439, Mann-Whitney test), showed a significantly increased translation efficiency (ratio of ribosome-bound fragments and mRNA input, P = 1.6 × 10−9, Mann-Whitney test, Figure 1I). Moreover, the translational efficiency of YTHDF1 unique targets was also significantly enhanced (P = 0.0036, Mann-Whitney test) (Figure 1I). These results suggest that YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 may cooperate in translation regulation.

We then randomly selected two genes: EEF1G and LRPAP1, which are regulated by YTHDF3, YTHDF1 and m6A. The binding clusters from YTHDF3, YTHDF1 and m6A peaks were displayed (Figure 1J). We observed that the protein levels of EEF1G and LRPAP1 were significantly decreased after knockdown of YTHDF3 or YTHDF1 (Figure 1K) or both (Supplementary information, Figure S2F), whereas their mRNA levels were kept unchanged (Supplementary information, Figure S2G and S2H). These data support the role of YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 in promoting translation efficiency. We also examined the protein levels of YTHDF3-specific substrates (ADAR1 and EIF2S3) upon YTHDF3 depletion. No significant changes were observed (Figure 1K and Supplementary information, Figure S2F), suggesting a cooperative mechanism of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 in translation regulation. This is further substantiated by the findings that RPS15 and EIF4E genes, two non-targets of both YTHDF1 and YTHDF3, failed to show any significant changes in their protein levels upon YTHDF1 or YTHDF3 depletion (Figure 1K and Supplementary information, Figure S2F-S2H).

On the basis of our findings we propose a working model for the YTHDF3-regulated mRNA translation events (Figure 1L). YTHDF3, in cooperation with YTHDF1, facilitates the translation of targeted mRNAs through binding to m6A-modified mRNAs and interacting with 40S and 60S ribosome subunits. The association of YTHDF1/3 with ribosomal proteins suggests an intriguing mechanism for their regulation of m6A-modified RNA translation. Translation initiation includes several steps: (1) 40S ribosomal subunit, eIF3 and the eIF2-GTP-tRNAMet complex are assembled into the 43S pre-initiation ternary complex; (2) mRNA is recruited to 43S through an association between eIF4G and eIF3; (3) the resulting 48S initiation complex scans along the 5′ UTR and encounters the AUG start codon, leading to eIF dissociation and 60S subunit binding to form the 80S ribosome2. YTHDF3 associates with ribosomal proteins of 40S/60S subunits, implying an indispensable role of YTHDF3 in translational regulation of m6A-modified mRNAs.

Translational regulation of m6A-modified mRNAs by m6A readers is a fascinating field in RNA metabolism that has just started to be unveiled recently. Recent reports showed that YTHDF1 promotes translation of m6A-modified mRNA2 and 5′ UTR m6A can promote cap-independent translation1, whereas YTHDF2 controls translation under heat-shock response3. We now provide the first evidence that YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation through interacting ribosomal 40S/60S subunits. Moreover, YTHDF3 significantly promotes translation efficiency of YTHDF1/3 common targets, but not YTHDF3 unique targets, indicating that YTHDF3 and YTHDF1 cooperate in fulfilling their regulatory role in translation, whereas the effect of YTHDF3 on its own unique targets may be linked to other RNA processing events. Considering the central role of ribosomal proteins in initiation of translation, it is plausible to suggest that YTHDF3 plays a significant role in modulating translation of m6A-modified mRNAs through sequential recruiting other translational effectors during translational process, which provides a new perspective of translational control of m6A.

Detailed Materials and Methods please see Supplementary information, Data S1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31430022), MOST2016YFC0900300, National Natural Science Foundation of China (31625016, 31500659 and 31400672), CAS Strategic Priority Research Program (XDB14030300). We thank BIG sequencing core facility for sequencing.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Supporting figure for validation of YTHDF3 partners.

Supporting figure for YTHDF3 in promoting translation.

Materials and methods

References

- Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, et al. Cell 2015; 163:999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, et al. Cell 2015; 161:1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhou J, Wan J, Gao X, et al. Nature 2015; 526:591–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, et al. Mol Cell 2016; 61:507–519. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun BF, et al. Cell Res 2014; 24:1403–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, et al. Nature 2014; 505:117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, et al. RNA 1997; 3:1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, et al. Nat Chem Biol 2014; 10:93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, et al. Cell Res 2014; 24:177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, et al. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, et al. Cell Rep 2014; 8:284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, et al. Nat Chem Biol 2011; 7:885–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zheng GQ, Dahl JA, Niu YM, et al. Mol Cell 2013; 49:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, et al. Cell 2012; 149:1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, et al. Nature 2012; 485:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting figure for validation of YTHDF3 partners.

Supporting figure for YTHDF3 in promoting translation.

Materials and methods