Abstract

Thyroid hormones are essential for normal brain development in vertebrates. In humans, abnormal maternal thyroid hormone levels during early pregnancy are associated with decreased offspring IQ and modified brain structure. As numerous environmental chemicals disrupt thyroid hormone signalling, we questioned whether exposure to ubiquitous chemicals affects thyroid hormone responses during early neurogenesis. We established a mixture of 15 common chemicals at concentrations reported in human amniotic fluid. An in vivo larval reporter (GFP) assay served to determine integrated thyroid hormone transcriptional responses. Dose-dependent effects of short-term (72 h) exposure to single chemicals and the mixture were found. qPCR on dissected brains showed significant changes in thyroid hormone-related genes including receptors, deiodinases and neural differentiation markers. Further, exposure to mixture also modified neural proliferation as well as neuron and oligodendrocyte size. Finally, exposed tadpoles showed behavioural responses with dose-dependent reductions in mobility. In conclusion, exposure to a mixture of ubiquitous chemicals at concentrations found in human amniotic fluid affect thyroid hormone-dependent transcription, gene expression, brain development and behaviour in early embryogenesis. As thyroid hormone signalling is strongly conserved across vertebrates the results suggest that ubiquitous chemical mixtures could be exerting adverse effects on foetal human brain development.

Brain development in all vertebrates requires thyroid hormones1,2. Severe thyroid hormone deficiency induces cretinism3. Recently, slightly lower or higher maternal thyroid hormone levels during early pregnancy were shown to be associated with decreased IQ and modified brain structure in children4. These data underline the previously underestimated role of thyroid hormones in early brain development5 and complement the well-established role for the hormone in later stages of brain development and maturation1.

Numerous studies have documented significant contamination of human populations and wildlife by multiple anthropogenic chemicals6,7. On average, over 30 anthropogenic chemicals are present in all American women, with 15 being ubiquitous, including in pregnant women6. Many of these chemicals are demonstrated or suspected thyroid hormone disruptors8,9, raising the question of whether current exposure to ubiquitous chemicals affects thyroid signalling and thereby early brain development. Even though certain xenobiotics have been investigated for their individual actions on specific endocrine axes, few studies have addressed their combined, or ‘cocktail’ effects. This lack of experimental data is striking given the increasing evidence that combinations of substances that individually have no adverse effect but can produce significant effects when tested as a mixture10,11.

To address how embryonic thyroid hormone signalling is affected by these 15 common chemicals, individually and in combination, we exploited the fluorescent X. laevis embryonic thyroid hormone reporter assay (XETA)12. This assay uses a transgenic line of Xenopus laevis, Tg(thibz:eGFP), which expresses GFP under the control of a 850 bp regulatory region of the TH/bZIP, a leucine zipper transcription factor highly sensitive to thyroid hormone regulation13,14. Using free-living tadpoles takes advantage of the high conservation of thyroid signalling across vertebrates, while providing access to early organogenesis, a developmental stage that is intractable for screening purposes in mammalian models. The XETA GFP readout informs on thyroid hormone disruption, with both increased and decreased fluorescence indicating altered hormone bioavailability.

Eleven of the 15 chemicals tested individually, exerted inhibitory or activating effects on thyroid hormone bioavailability in XETA. As synergistic effects of chemical mixtures without individual effects have been reported10,15, we established a mixture of the 15 ubiquitous chemicals at concentrations reported in human amniotic fluids (Table S1). We used this mixture at three different concentrations, where 1x represents the concentrations of individual chemicals reported in human amniotic fluid. Effects of exposure were determined on thyroid hormone bioavailability (XETA), brain gene expression and structure, and behaviour. Significant and dose-dependent effects were found in all assays, raising the question of potential adverse effects of current chemical exposures on foetal brain development.

Results

In this work we analysed the consequences of human amniotic fluid contaminant exposure during embryonic development on thyroid hormone signalling and brain development. We first tested the thyroid hormone disruptive capacity of chemicals, individually and as a mixture, using a validated assay, the XETA12. Following the XETA, effects of chemical exposure were analysed on brain gene expression, neural proliferation, neuron and oligodendrocyte number and volume, and swimming behaviour.

Eleven chemical contaminants of amniotic fluid disrupt thyroid hormone signalling

In all experiments X. laevis tadpoles at stage NF4516 (non-feeding stage corresponding to one week post fertilisation development), were exposed for 72 h (at 23 °C), at which point they reached stage NF46/47. At this latter stage the thyroid gland starts to be functional. In humans, the thyroid gland becomes functional around 3 to 4 months of foetal life. Thus our exposure period corresponds to a period of human foetal development where only maternal thyroid hormone is available. In our model, the maternal thyroid hormone source is present in the yolk. Each chemical was screened in XETA at least at three concentrations, both alone (Fig. S1a–g) and against a tri-iodothyronine (T3) challenge (5 × 10−9 M, Fig. 1). The T3 spike stimulates production of TRß (Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta) that is inducible at this stage (ref. 17 and Fig. 2e), thereby amplifying responses (compare Fig. 1 and S1). The dose response relationships tested covered ranges found in human fluids, maternal blood or urine, cord blood serum or amniotic fluid (Table S1 and references therein). Note that Table S1 gives concentrations in molarity and μg/L as both units are commonly used in relevant studies.

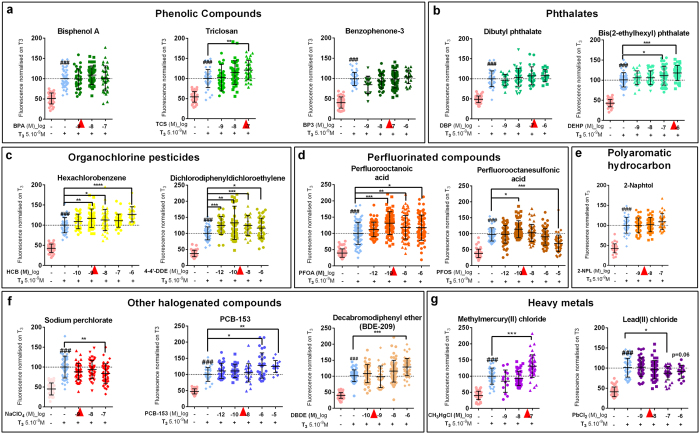

Figure 1. Thyroid disrupting activity of individual chemicals assessed with XETA.

Screening of thyroid disrupting activity of molecules measured in humans with the Xenopus Embryonic Thyroid Assay (XETA), based on the quantification of fluorescence-using the transgenic TH/bZip-eGFP e.g. [(Tg(thibz:eGFP)] line. Fifteen compounds were tested at different concentrations in presence of T3 5 × 10−9 M for 72 h. Scattered plots are shown with mean +/− SD of three to five independent experiments pooled (normalised on T3 to 100%). The GFP fluorescence in whole tadpoles (mainly heads) was measured and quantified after 72 h exposure. (a) Phenolic compounds: BPA, Triclosan and Benzophenone-3. (b) Phthalates: DBP and DEHP. (c) Organochlorine pesticides: HCB and 4′4-DDE. (d) Perfluorinated compounds: PFOA and PFOS. (e) Polyaromatic hydrocarbon: 2-Naphtol. (f) Halogenated compounds: Sodium perchlorate, PCB-153 and BDE-209. (g) Metals: Methylmercury and Lead chloride. Red arrowheads indicate concentrations of chemicals used in mix 1x (Table S1). Statistics were done with non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Hashes (###) represent p < 0.001, T3 vs Control using column to column comparison (non parametric Mann Whitney).

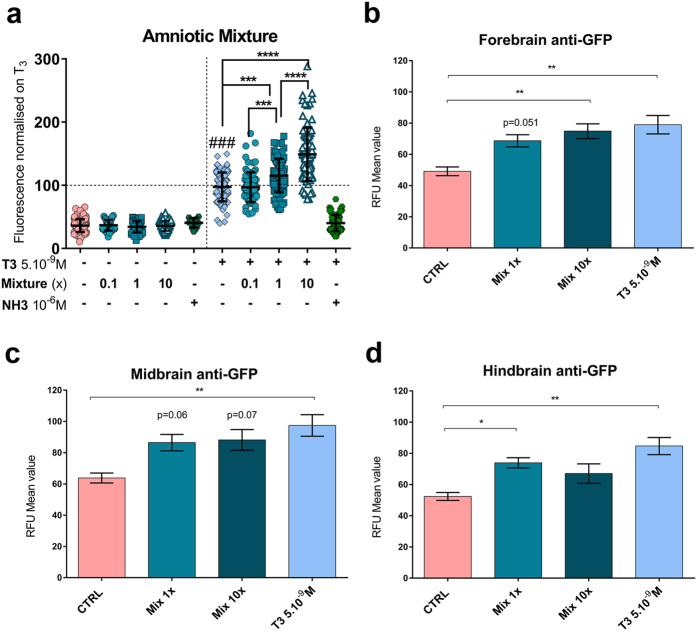

Figure 2. Thyroid disrupting activity of mixture assessed with XETA.

Screening of thyroid disrupting activity of mixture of 15 molecules at concentrations measured in human amniotic fluid (mix 1x) 10 times more concentrated (mix 10x) and 10 times less concentrated (mix 0.1x) using Tg(thibz:eGFP) tadpoles. (a) GFP fluorescence (mainly localised in heads) of whole tadpoles exposed to mixture at 0.1x, 1x, 10x or a TR antagonist NH-3 (1 μM) with (right) or without (left) a T3 spike at 5 × 10−9 M. Quantification was done on images taken at 72 h exposure. Scattered dot plots are shown with mean +/− SD of five independent pooled experiments (normalised against T3). Statistics used non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Hashes (###) represent p < 0.001, T3 vs Control using column-to-column comparison. (b–d) Histograms represent mean (+/SEM) of relative fluorescence units (RFU) of GFP in forebrain (b), midbrain (c) and hindbrain (d) of tadpoles exposed to mixture for 72 h in the absence of T3. Regions were delimited manually on ventral brain images (see Fig. S2c). Statistics used non parametric Kruskal Wallis compared to CTRL.

Eleven of the 15 chemicals screened were positively identified as Thyroid Disruptors (TDs). Among the phenolic compounds tested, triclosan (TCS, an anti-microbial) significantly disrupted thyroid hormone signalling at 10−7 M (Fig. 1a). Two phthalates (plastic softeners) were tested: dibutyl phthalate (DBP) and diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) (Fig. 1b). DEHP showed significant TD effects at 10−7 M, in the range of human amniotic fluid levels. Both organochlorine pesticides tested, hexachlorobenzene (HCB) and 4-4′ dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE, the main metabolite of DDT) (Fig. 1c), increased fluorescence from 10−9 M and 10−12 M onwards respectively. HCB significantly increased GFP at 10−9 M, 10−8 M and 10−6 M. A non-monotonic, inverted ‘U’-shaped dose response was observed with the surfactant perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) (Fig. 1d), with activation (p < 0.05) at 10−10 M and inhibition (p < 0.001) at 10−5 M. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (Fig. 1d) enhanced transcriptional activity from 10−10 M to 10−6 M. All the other halogenated compounds had significant TD effects at the highest doses tested (Fig. 1f): perchlorate inhibited (10−7 M) while a polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB-153) and a decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) activated GFP at 10−6 M. Two environmentally relevant heavy metals, known for their neurotoxic effects, were also screened (Fig. 1g). Methyl mercury significantly increased fluorescent at 10−7 M, whereas lead chloride induced a significant decrease at 10−7 M.

A mixture of common chemicals dose-dependently disrupts thyroid hormone signalling during early brain development

Synergism of apparently inactive compounds has been reported10,15. We established a mixture (mix 1x) of each of these 15 chemicals at concentrations reported in human amniotic fluid (Fig. 1a–g (red arrowheads), Table S1) and tested it at 0.1x, 1x and 10x concentrations. Exposure of GFP-reporter tadpoles to the mixture induced a dose-dependent increase in fluorescence, by 18% (1x) and 49% (10x) compared to T3 alone suggesting increased T3 bioavailability (Fig. 2a). Exposure to mix 0.1x had no significant effect in XETA. The T3 dependency of the effects was confirmed using a T3 antagonist NH-318 (Fig. S2a,b). NH-3 reduced the GFP signal induced by mix 10x both in the absence and the presence of T3 (Fig. S2a, left and right panel). In the case of mix 10x tested in the presence of the T3 spike, the GFP response was fully abrogated (Fig. S2a, right panel). Without the T3 spike, no significant modification of fluorescence was detected at the level of the whole tadpole for any concentration of the mixture nor for any single chemical, other than for BDE-209 at 10−6 M (Fig. S1f). However, interference from epidermis and skull could mask brain specific responses. To determine whether mixture exposure affected brain GFP expression, we dissected the brains from tadpoles that had been exposed to mixture in the absence of exogenously added T3 and carried out anti-GFP immunohistochemistry. As indicated in Fig. 2b–d and S2c, a significant increase in fluorescence was measured. Notably, when signal intensity was analysed according to brain region (region of interest forebrain, midbrain or hindbrain) exposure to mix 1x and 10x increased GFP in the hindbrain and the forebrain respectively. The most marked effects were found in the forebrain, where GFP levels in mix 1x and 10x exposure were significantly increased (p = 0.05, and p < 0.01, respectively), showing brain region specific action of this chemical mixture.

Exposure to chemical mixture modifies thyroid hormone-dependent and neuronal development-related gene expression in brain

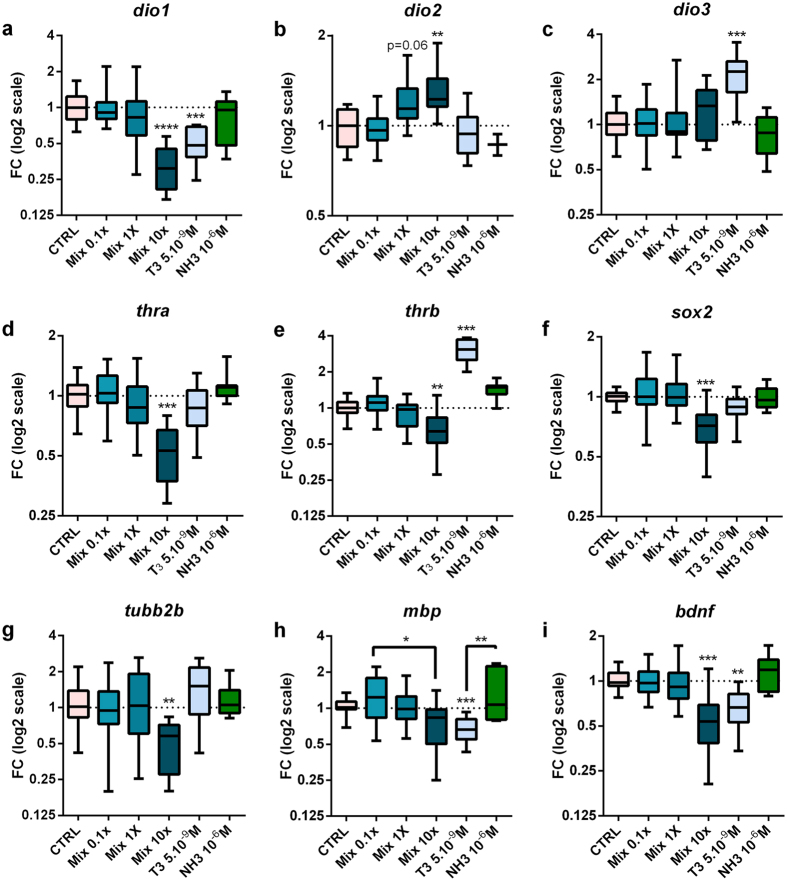

Having established that TD effects were measurable in brains without an exogenous T3 spike, we next examined effects of exposure on brain development using the mixture without T3 co-treatment, thereby relying on endogenous T3 signalling (Figs 3 and 4, S3–S6). qPCR was used to examine gene expression in dissected brains (Fig. 3, S3, S4) following exposure to the mixture, T3 (5.10−9 M) or NH-3 (10−6 M). Mixture exposure (72 h) modified expression of multiple genes, including those encoding the deiodinases (enzymes that determine T3 bioavailability)19, thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), thyroid hormone transporters (THTs) and genes implicated in neural stem cell renewal and neuronal differentiation. Expression of dio1, encoding deiodinase1 (D1, an activating or inactivating deiodinase)20, was significantly decreased, whilst expression of dio2, encoding deiodinase2 (D2, an activating enzyme) was increased (Fig. 3a,b) as suggested in Fig. S1h (T4 co-treatment). Genes encoding THTs were also significantly modulated by exposure to mixture (Fig. S4m–q). Expression of both TRα and TRβ mRNA was significantly down-regulated by exposure to mix 10x (Fig. 3d,e). Amongst the T3-target genes affected by exposure to mix 10x, when compared to mix 0.1x, were the pluripotency gene sox2 (Fig. 3f), the neurotrophic factor bdnf (Fig. 3i) and genes implicated in neuronal and oligodendrocyte differentiation, namely tubulin2b, mecp2, dcx (Fig. 3g and S3b) and mbp (Fig. 3h). Addition of exogenous T3 resulted in similar or amplified expression of T3 target genes (Fig. S3).

Figure 3. Mixture exposure modifies thyroid hormone and neuronal development related gene expression in brain.

Wild type NF45 X. laevis tadpoles were exposed to mixture for 72 h in the absence of T3. For each concentration tested between 7 to 12 pools of three brains were used from at least four independent experiments. Total brain mRNA transcripts levels were quantified using RT-qPCR: (a), dio1 (b), dio2 (c), dio3 (d), thra (e), thrb (f), sox2 (g), tubb2b (h), mbp (i), bdnf. Relative fold changes were calculated using geometric mean of ef1a and odc as normalizers. Results are presented as fold changes using a log2 scale and DMSO-treated animals (CTRL) values for the 1.0 reference. Statistics were done on dCts and used Kruskal-Wallis tests (Box plots median and quartiles), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

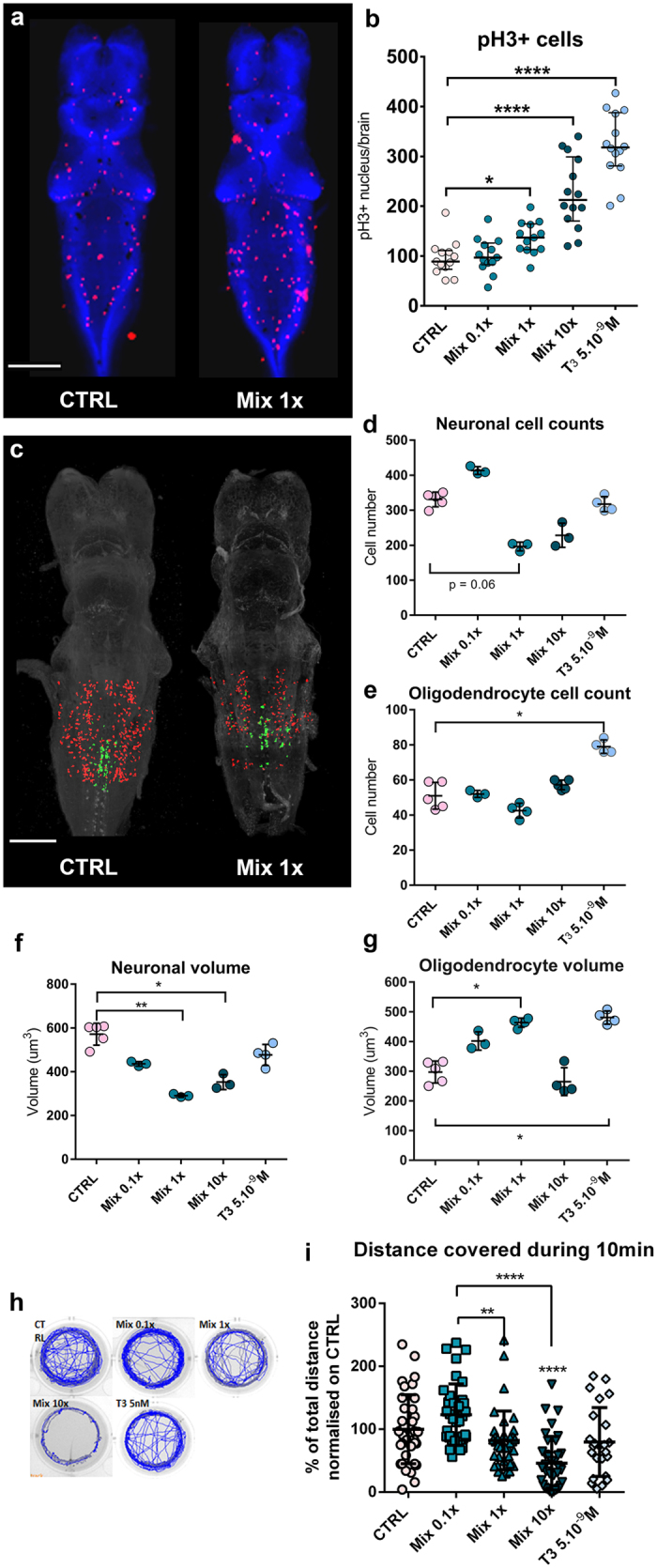

Figure 4. Mixture enhances proliferation in brain, modifies neural cell populations and behaviour.

(a) Dorsal views of brains of mixture exposed wild type NF45 X. laevis tadpoles. Immunohistochemistry used the anti-PH3 antibody (red, mitosis) and DAPI (blue, nucleus). Scale bar, 200 μm. (b) Numbers of proliferating cells in (PH3 + cells) in tadpole brains following mixture exposure. n = 13 brains per condition, 5 independent experiments pooled (representative number of positive cells in each brain). Statistics used 2-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test (Medians ± SDs, *p < 0.05,****p < 0.0001) (c) CLARITY imaging illustrating the region of interest delimited for analysis in (d–g) on hind brain. Examples of control (left) and mix 1x exposed (right) double transgenic tadpoles Tg(nβt:DSRED) (neurons, red) and Tg(Mmu.mbp:NTR-eGFP) (oligodendrocyte, green). Scale bar, 200 μm. (d–g) Quantification of CLARITY signals obtained for each fluorescent signal in hindbrain. Neuron (d) and oligodendrocyte (e) numbers and cell volumes (f,g), n = 3 to 5 brains, Statistics used non parametric Kruskal Wallis ANOVA and Dunn’s post-test (Means ± SDs, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) (h) Wild type NF45 X. laevis tadpoles were exposed to DMSO (CTRL), or mixture (0.1x, 1x, 10x), T3 5 × 10−9 M for 72 h for mobility analysis. Example of total distance covered in 10 mins under 30 secs/30 secs light (blue lines)/dark (grey lines) cycles by one tadpole per condition (i) Mean distance covered during 10 mins under different conditions. Distance is normalized versus controls for 4 independent experiments with n = 12 per experiment. Representation uses scattered dot plots Mean +/− SD. Statistics used meta-analysis with Kruskal-Wallis. Note that stars directly over a group indicates significant difference with CTRL group (Error bars indicate s.e.m, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

Chemical mixture enhances cell proliferation in brain and modifies neural cell populations

Modulation of neural differentiation genes suggests that exposure to the chemical mixture could affect progenitor proliferation as well as neuronal and glial cell numbers. We verified whether this was the case using immunocytochemistry for phosphorylated histone H3 (P-H3), a mitotic marker, on mixture-exposed brains21. Exposure induced a dose-dependent increase in proliferating cells (PH3+ cells), from 96 ± 10 (mean ± SEM) to 136 ± 9 with mix 1x and 225 ± 19 with mix 10x (Fig. 4a,b).

To further examine if neural lineage decisions were modified by mixture exposure, dissected brains were subjected to CLARITY22 in order to visualize the whole brain (Videos S5a,b,c) and quantify neuronal and oligodendrocyte populations, as well as individual cell volumes (Fig. 4c–g). We used double transgenic tadpoles Tg(Mmu.mbp:GFP,nβt:DsRed), in which fluorescent markers label mature oligodendrocytes in green and differentiated neurons in red. The oligodendrocyte marker (GFP) is driven by myelin basic protein (mbp) regulatory elements from mouse23. The neuronal marker (DsREd) is driven by neural β tubulin (nβt) regulating elements24. See material and methods and Fig. 4c for further explanations. Disruption to thyroid hormone signalling was measured in the hindbrain (Fig. 2f), where both oligodendrocytes and neurons are present. Here exposure to mix 1x induced a decrease in differentiated neuron numbers that almost reached significance (Fig. 4d, p = 0.06). Neuron and oligodendrocyte volumes were inversely affected with exposure to mix 1x, decreasing neuron volume significantly while increasing that of oligodendrocytes (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 respectively, Fig. 4f,g).

Chemical mixture exposure dose-dependently alters tadpole mobility

We next addressed the phenotypic consequences of short-term (72 h) exposure since embryonic motor behaviour changes can indicate small modifications in the neural circuitry controlling movement25. For this purpose, we used a video tracking system and recorded the total distance covered by individual tadpoles with 30 secs alternating light and dark cycles for total of 10 mins (Fig. 4h–g, S6a–c and Videos S6,d,f). Figure 4h shows representative traces of single tadpoles exposed to different concentrations of mixture or T3 (5.10−9 M). The total distance travelled decreased dose-dependently with increasing mixture concentration and in the case of mix 10x, by more than 50% (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4i). These differences were observed over the 10 minutes tracking (Fig. S6b) and independently of light or dark periods even though tadpoles are stimulated by light (Fig. S6c).

Discussion

There has been a 300-fold increase in the number and quantity of chemicals released into the environment in the last 50 years26. Many chemicals are now ubiquitous in the environment and in humans, including in pregnant women6. In this study, the rationale was to select chemicals found ubiquitously, test their thyroid disrupting effects individually and then, to represent intra-uterine exposure, test a mixture at concentrations found in amniotic fluid.

Focus on Thyroid disruption

We emphasised disruption of thyroid hormone signalling because (i) of the tight dependence of brain development on maternal levels of thyroid hormone4 (ii) a 3 day screening assay undergoing OECD validation is available and (iii) this hormonal axis is highly sensitive to endocrine disruption27. This sensitivity could relate to the complexity of thyroid hormone production that includes iodine uptake through specific symporters and a highly-regulated organification process28, but also to specific enzymes controlling thyroid hormone availability in peripheral targets1. A salient point is that thyroid hormones are the most complex halogenated molecules produced by vertebrates and the only one to contain iodine. Interestingly, eight of the 15 compounds tested here are halogenated, all of which showed thyroid signalling disruption, while most non-halogenated molecules (i.e. BPA, napthol and benzophenone-3) were inactive in the XETA test at relevant concentrations. Only two non-halogenated molecules were active: mercury and lead. Mercury chelates selenium29, an element required for synthesis and activity of all deiodinases30. This feature links mercury to interference with thyroid hormone activation/inactivation via deiodination, through selenocysteine deiodinases that are active in Xenopus tadpoles at this developmental stage20,31. These enzymes finely tune the bioavailability of the active form of thyroid hormone (T3) in each cell.

Increased TH signalling with individual compounds and mixtures

These deiodination processes, and more generally the complexity of thyroid hormone signalling, could also contribute to explaining why the majority of individual chemicals and the mixture induced increase in thyroid hormone availability (after 72 h). It is worth pointing out that we did not observe additive effects of the individual compounds used as a mixture. Indeed, at the concentrations used in the mixture, certain compounds could be exerting negative effects whilst other exert positive effects. Given the multiple possible pathways affected, the overall readout on transcription could be muted. Similarly, the effect of one compound could override that of others. Previous epidemiological and experimental data on some individual chemicals could have led to predict decreased thyroid hormone availability. For instance, high PCB or BDE exposure depresses circulating thyroid hormone levels in humans and different species32,33. However, many of these experiments were based on long term exposure where increased clearance is subsequent to transient interactions with distributor proteins. In such cases, one could well expect a transient increase in thyroid hormone availability as observed in our experimental model34. Moreover, brain T3 increased bioavailability is also strongly suggested by the mixture-induced increased expression of dio2 encoding for activating enzyme D2 (Fig. 2b). In this light, it should be borne in mind that our in vivo screening readout encompasses multiple levels of thyroid hormone signalling axis which could, by definition, indicate multiple levels of disruption. Indeed, this screening model offers the huge advantage of detecting chemicals interacting directly or indirectly with TH signalling whatever the level of disruption, but requires deeper investigations to identify specific mode of action. The thyroid disruption property of the mixture and the subsequent fluorescence increase, while possibly indirect for certain components, is clearly shown by the co-exposure with antagonist NH-3 that abrogated 10x mixture induced fluorescence in presence or absence of T3 (Fig. S2a and b).

Early stages of development are considered to be amongst the most vulnerable windows for exposure as they represent ongoing organogenesis35. Studying mammalian embryos at these early stages is challenging due to their intrauterine development and limited numbers of embryos per mother. Hence, there is a need for more tractable models. The free-living amphibian X. laevis tadpole, provides large-scale screening tools and allows easy access to early developmental stages. A further advantage of the Xenopus system is the high homology of thyroid hormone signalling with mammals that is not fully shared by other free-living aquatic models such as teleosts.

After having established the thyroid disrupting effect of the mixture, rationale was then to mimic an embryonic exposure during a critical period for brain development. For that purpose mixture alone was applied to embryos before thyroid gland formation during neurogenesis. Our results show that mixture exposure affects T3–dependent transcription, cellular responses and behaviour. These multiple early developmental effects could well be interrelated.

Among the brain-expressed genes significantly modified were numerous actors implicated in thyroid hormone signalling, such as deiodinases, TRs, thyroid hormone transporters, and thyroid hormone targets including determinants of neural development. Expression of the activating/inactivating deiodinase, D1 was significantly decreased, whilst that of the activating deiodinase, D2, was significantly increased. These findings fit with the results from the XETA test that displayed a dose-dependent increase in thyroid hormone signalling following chemical mixture exposure, reflecting greater bioavailability of the hormone.

Relevance of these results to human brain development

At first sight, given the essential role of thyroid hormones in brain development, one might think that more hormone is not problematic. However, a number of results counter this idea. First, Korevaar et al.4 in their study of mother/child pairs, showed that maternal hyperthyroidism has an equally adverse effect on children’s IQ and brain structure, as does maternal hypothyroidism. Second, many rodent studies have revealed deleterious effects of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism during brain development36. Finally, during neurogenesis, thyroid hormones act as differentiation signals, directly repressing the pluripotency gene Sox237. Early exposure to excess thyroid hormone could therefore induce precocious differentiation of the neural progenitor populations, with ensuing modifications of brain size and organisation. In the present study, expression of sox2 was down-regulated by exposure to mix 10x, as was the expression of a number of neural markers, including markers of neuronal (tubb2b) and oligodendrocyte (mbp) differentiation. Similarly, expression of an essential nerve growth factor, bdnf, was significantly decreased. BDNF variants have repeatedly been linked in human studies to autism spectrum disorder (ASD)38,39 as well as animal models of this neurodevelopmental disorder40,41. In our model, most of the changes in brain gene expression were only seen following exposure to mix 10x. However, it should be borne in mind that in this experimental context exposure is limited to 72 h. During this time it is probable that many of the chemicals are catabolised by the tadpoles, which are metabolically competent at this stage42. A similar situation is expected in the uterine environment, but in this case metabolites can accumulate in the amniotic fluid and prolong exposure if not removed through the umbilical cord blood and excreted by the mother. Moreover, from a legislative point of view, tolerable daily intake is calculated from no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) in animal models with a security factor of 100 (10 for intra and 10 for interspecies differences). This also means that any result obtained in an animal model with 10 times human levels is relevant and highlight the absolute need for a better legislation.

Strikingly, in tadpoles exposed to mixture, we found that exposure to the chemical mixture at 1x concentration significantly increased proliferation in neurogenic zones (Fig. 4a,b) but also oligodendrocyte volume (Fig. 4g) whilst decreasing that of neurons (Fig. 4f). Interestingly, autopsies of brains from ASD patients have revealed changes in neuronal cell volumes43,44. Changes were also found in ratios of oligodendrocyte to neurons, with numbers of neurons being significantly reduced following short-term exposure to the chemical mixture (Fig. 4d). Again, this finding has relevance to human data. Analyses of maternal thyroid hormone levels during early pregnancy revealed that both maternal hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can result in changes in children’s brain structure with modifications of grey to white matter ratios4, reflecting changes in neuron to oligodendrocyte numbers.

Finally, we found that the molecular and cellular modifications resulting from mixture exposure led to marked behavioural changes as assessed by mobility tracking. Exposure to mixture significantly reduced total distance travelled by tadpoles, with mix 10x reducing distance travelled by over 50%. Maternal hypothyroidism increases the risk for many neurodevelopmental diseases characterised by behavioural problems, including ASD and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)45,46. We provide evidence that most of the ubiquitous compounds measured in human amniotic fluid disrupt thyroid signalling alone or if applied as a mixture. We also show that mixture exposure results in a number of T3 –like effects in expression of key genes and neural proliferation in the brain with ensuing effects on behaviour.

Many chemicals in this mixture could also affect other endocrine pathways beside thyroid hormone. An example is phthalates that are known to affect androgen signalling47 but exposure to which has also recently been linked during pregnancy with altered maternal thyroid levels48. Importantly, epidemiological studies show that maternal exposure to many of the chemicals studied here can affect offspring IQ and/or neurodevelopmental disease risk. This is the case for PCBs that have been linked to IQ loss49 and increased ADHD risk50. As to phthalates, numerous members of this vast chemical category, have also been linked to IQ loss51 and risk for different forms of neurodevelopmental disease52,53. Further, multiple studies show that increased maternal perchlorate levels correlate negatively with offspring IQ54. Lastly, PBDEs represent yet another large chemical category where maternal exposure has repeatedly been associated with IQ loss and increased ASD risk55.

Conclusions

The above results demonstrate that early embryonic exposure to a mixture of common chemicals alters thyroid hormone signalling, brain structure and behaviour. These findings can be placed in the context of recent epidemiological studies showing that small variations in maternal thyroid hormone during early pregnancy impact children’s IQ4. Our results would thus argue for an urgent revisiting of the regulatory scenario used to determine how common chemicals and their mixtures affect human health.

Material and Methods

Xenopus laevis strains and rearing

Xenopus laevis strains were maintained in accordance with institutional and European guidelines (2010/63/UE Directive 2010), all procedures and methods used are following institutional and European guidelines (2010/63/UE Directive 2010) and have been approved by the local ethic committee (Cometh) under the project authorization No. 68-039. The transgenic X. laevis lines used were; Tg(thibz:eGFP) (homozygous)14 and a double transgenic (heterozygous) Tg(Mmu.mbp:NTR-eGFP,nβt:DSRED) obtained by crossing Tg(Mmu.mbp:NTR-eGFP)23 with Tg(nβt:DSRED)24. In Tg(thibz:eGFP) GFP is expressed under the control of 850 bp of the regulatory region of THbZIP transcription factor, a TH regulated gene. In Tg(Mmu.mbp:NTR-eGFP), an oligodendrocyte marker (GFP) and an enzyme nitroreductase (NTR) are driven by myelin basic protein (mbp) regulatory elements from mouse. Note that nitroreductase can specifically induce apoptosis in oligodendrocytes23, but we did not use this property in this study. In Tg(nβt:DSRED), the neuronal marker (DsRED) is driven by neuronal β tubulin (nβt) regulating elements. Tadpoles were obtained by natural breeding between wild type (WT) and/or transgenic animals and raised as described12.

Chemicals

The following chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France): bisphenol-A (BPA purity >99%), triclosan (TCS >97%), benzophenone-3 (BP3_98%), decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209 98%), sodium perchlorate (>98%), 4-4′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylen (4,4′-DDE 99%), hexachlorobenzene (HCB 99.9%), dibutylphtalate (DBP 99%), diethylhexylphtalate (DEHP 99%), PCB-153, 2-Naphtol (99%), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS >98%), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA >98%), methyl mercury chloride (>99.9%), lead chloride (98%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetone, 3,3′,5,5′tetraiodo-L-thyronine T4 >98%) and triiodothyronine (T3 99%). NH-3, a thyroid hormone antagonist18 was synthesized by AGV Discovery (France), absence of contamination by benzofurane was verified56. All chemicals were dissolved at 10−1 M in DMSO, with the exception of HCB (10−1 M in acetone) and BDE 209 (10−2 M in DMSO). These solutions were aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until use. T3 was prepared in 30% NaOH, 70% milliQ Water at 10−2 M concentration, aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until use. The chemical mixture was prepared at 105-fold concentration by mixing appropriate volumes of stocks as described in Supplementary Table 1, aliquoted and stored at −20 °C.

Chemical exposure protocol for Xenopus embryonic thyroid assay (XETA) screening

Screening for thyroid disrupting chemicals was carried out using XETA as previously described using stage NF45 tadpoles, from Tg(thibz:eGFP) transgenic X. laevis at stage NF45 (1 week old)12. Fifteen tadpoles were placed per well in 6 well plates (TPP Switzerland), containing either control solvent (DMSO) or chemical. DMSO concentration was 0.01% in all treatments and the pH remained unchanged (Fig. S2). Plates were placed at 23 °C for 3 days. The chemical solutions were renewed every day, at regular 24 h intervals. After 72 h exposure, tadpoles were anesthetized with 0.01% MS-222 and placed dorsally, one per well in a black, conic based-96 well plate (Greiner). Images were acquired with a 25x objective and 3 s exposure using an Olympus AX-70 binocular equipped with long pass GFP filters and a Q-Imaging Exi Aqa video camera. QC Capture pro (QImaging) software was used for image acquisitions and quantifications were carried out using ImageJ. All pictures of a group (chemical and concentration) were stacked, the 3 layers of RGB pictures were split and the red and blue channels subtracted from the green channel to exclude non-specific signals (integrated density of all images were used). Quantifications were carried out on whole pictures and data was expressed in relative units of fluorescence (RFU). All values were normalized to the T3 group (100%). GraphPad Prism 6 software was used for graphs and statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis for XETA

Results are presented as scatter dot blots with mean +/− SD. Experiments were validated with a column to column comparison between the control and T3 group using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. T3 spiked and non-spiked mode were analysed separately using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis’ followed by Dunn’s test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05(*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001(***) and p < 0.0001(****).

RNA extraction and gene expression analysis

For gene expression analysis, wild type X. laevis tadpoles were subjected for 72 h to chemicals as previously described above. After 72 h, tadpoles were anesthetized in 0.01% MS-222, and brains dissected on ice under sterile conditions. Two different RNA extraction methods were used and gave comparable results. Initially brains were dissected and a pool of three brains were placed in 1.5 ml Sorenson tubes, 4 tubes per condition (control, chemically treated), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. RNA extraction used QIAGEN RNeasy micro plus kits following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The second method used a pool of two dissected brains placed in 1.5 ml Sorenson tubes containing 100 μl lysis buffer (provided in RNAqueous micro kit (Ambion)), 5 tubes per condition (control, chemically treated etc.) flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. RNA extraction used RNAqueous Micro kit (AMBION, ThermoFischer). RNA concentrations were determined using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ThermoScientific, Rockford, IL) and RNA quality verified using BioAnalyzer (Agilent) where we only validated samples with RIN >8. Total extracted RNA (500 ng) was used for reverse transcription using a High Capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied BioSystem, Foster City, CA). The single stranded complementary DNA (cDNA) obtained was used as a template for qPCR.

Quantitative PCR was carried out using QuantStudio 6 flex (Life technologies) on 384 well-plates, with a standard reaction per well containing 1/20 diluted cDNA as template (1 μl per well) plus 5 μl of mix (Power SyBR mix, Applied BioSystem). Relative concentrations of cDNA were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method57 for the analysis of relative changes in gene expression. For normalizing, a geometric mean of endogenous controls (elongation factor alpha (ef1alpha) and ornithine decarboxylase (odc)), were used as the two reference genes.

Statistical analysis for qPCR

Data are presented as fold change (2−ΔΔCt) using a log (base2) scale plotted as a traditional box and whisker plot by Tukey where the bottom and top of the box represent the 25th lower and 75th percentile, and the median is the horizontal bar in the box. Statistical analyses were performed on delta Cts using non-parametric Kruskal Wallis’ test followed by Dunn’s post-test (all compared to the control group). Certain column to column comparisons were done when necessary and have been annotated in the figures accordingly. Significance was determined at p < 0.05(*), p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001(***).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cell proliferation

After 72 h exposure, tadpoles were euthanized in MS-222 1 g/l, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h at RT (room temperature), placed in PBS for either immediate use or in cryoprotectant and stored at −20 °C. Primary antibodies: anti-Ser10 phosphorylated on Histone H3, rabbit, (06–570 Millipore) or mouse (05–806 Millipore) used at 1/300 dilution for in toto immunohistochemistry. All positive nuclei were counted from 5 independent experiments with n = 2 to n = 5 per experiment and statistical analyses performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-test (all compared to control group). Significance was determined at p < 0.05(*) and p < 0.0001(****).

Behaviour analysis –total distance covered

Mobility of NF45 tadpoles, exposed (72 h) to mixture (0.1x, 1x, 10x), T3 5.10−9 M or solvent (DMSO) was assessed using the DanioVision (Noldus) behaviour analysis system. After an initial rinse, tadpoles of each group were placed one per well of a polypropylene transparent 12 well plate (TPP, Switzerland) in 4 ml of Evian water. Tadpoles were left to accommodate for 15 minutes before placing the plate in the Danio Vision Module. This module consists of an opaque box in which the plate holder under an infrared camera. Plates were recorded for 10 mins as a movie (example in videos S6 e–g). Light was used to stimulate movement ie periods of 30 seconds alternating light and dark cycles. Maximal light stimulus (5 K Lux) was used during light on. Distance travelled during the 10 mins was analysed using EthoVision software (11.5, Noldus, Wageningen, The Netherlands).

Statistical analysis of mobility

Differences between control, mix 0.1x, mix 1x, mix 10x were analysed using the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis’ test. Differences were significant at p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.0001(****).

Clarification and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for neuronal and oligodendrocyte cell populations

Transgenic tadpoles were obtained from crossing the double transgenic X. laevis line carrying pmbp:NTR-eGFP and pnβt:DsRed with wildtype X. laevis. Fluorescent tadpoles were sorted at stage NF45 and exposed to chemical treatment as described previously. After 72 h treatment, the tadpoles were anaesthetized in MS222 1 g/l, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h at RT and stored (0.4% PFA, 4 °C) until clarification.

CLARITY

Fixed tadpoles and dissected brains were subjected to clarification following the CLARITY protocol58 with some tissue-specific adaptations: samples were infused in a pre-cooled solution of freshly prepared hydrogel monomers (0.01 PBS, 0.25% VA-044 initiator (wt/vol), 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (vol/vol), 1% PFA (wt/vol), 4% acrylamide (wt/vol) and 0.0025% bis-acrylamide (wt/vol)) for 2d at 4 °C. After degassing the samples, hydrogel polymerization was triggered by replacing atmospheric oxygen with nitrogen in a desiccation chamber for 3 h at 37 °C. The superfluous hydrogel was rinsed off and samples transferred into embedding cassettes for lipid clearing. Passive lipid clearing was performed at 40 °C for 8 d in the clearing solution (8% SDS (wt/vol), 0.2 M boric acid, pH adjusted to 8.5) under gentle agitation. Subsequently, the samples were thoroughly washed in 0.01 M PBS, tween 0.1% (wt/vol, PBSt, RT, 2d) with gentle agitation.

Immunostaining of clarified samples

CLARITY-processed brains were incubated in blocking solution (0.01 M PBS, 0.1% tween 20 (vol/vol), 1% TritonX100 (vol/vol), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (vol/vol), 10% normal goat serum (vol/vol), 0.05 M glycine) overnight at 4 °C. Samples were further incubated in staining solution (0.01 M PBS, 0.1% tween 20 (vol/vol), 0.1% Triton X100 (vol/vol), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (vol/vol), 2% normal goat serum (vol/vol), 0.05% azide (vol/vol)) with primary antibodies (chicken anti-GFP, Avès Labs, 1:400 and rabbit anti-DsRed, Clontech, 1:400) for 7d at RT under gentle agitation. After 2 washes with PBSt, samples were incubated in a staining solution with secondary antibody (goat anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen, 1:600 and goat anti-rabbit 555, Invitrogen, 1:600) for 7d at RT. Samples were then washed for 48 h in PBSt.

Imaging using a high refractive index solution

A fructose-based high refractive index solution (fHRI) was prepared as follows; 70% fructose (wt/vol), 20% DMSO (wt/vol) in 0.002 M PBS, 0.005% sodium azide (wt/vol). The refractive index of the solution was adjusted to 1.4571 using a refractometer (Kruss). The clarified samples were incubated in 50% (vol/vol) fHRI for 6 h and further incubated in fHRI for >12 h. For imaging, samples were mounted in 1% (wt/vol) low melting point agarose and covered with fHRI. Whole-mount brain fluorescence was captured using a Leica TCS SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a Leica HC FLUOTAR L 25x/1.00 IMM motCorr objective.

Image treatment and statistical analysis

Image stacks were converted from their native 12 bit lif-format to series of 8bit-pngs using CLAHE (contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization, Zuiderfeld, 1994) for ImageJ (Rasband et al., http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) as implemented in fiji (Saalfeld, http://fiji.sc/Enhance_Local_Contrast_%28CLAHE%29). The parameters for CLAHE were empirically tested and set to a block size of 127, 256 bins and a slope of 3 (default values). CLAHE enhances the contrast and intensity of weak signals significantly while not over-saturating strong signals. Images were analysed using Imaris software (Imaris software package, Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland). The areas of individual neurons and oligodendrocytes were determined and used to calculate the mean size of individual cell volume. At least 3 brains from independent experiments were used for each experiment shown.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Fini, J.-B. et al. Human amniotic fluid contaminants alter thyroid hormone signalling and early brain development in Xenopus embryos. Sci. Rep. 7, 43786; doi: 10.1038/srep43786 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gérard Benisti, Philippe Durand and Jean-Paul Chaumeil for excellent animal care and Christelle Angely for help on individual chemical screening. We are grateful for all the comments of our colleagues and collaborators on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), and from French Ministry of Environment MEDD, PNRPE_THYDIS 2013-N°CHORUS-2101207963, PNREST THYPEST EST-2014-122, TOXSYN ANR-13-CESA-0017-01, European Union contracts DEVCOM_GA N°607142 and EDC MIX RISK_GA N°634880, and Investissement d’avenir - ANR-II-INBS-0014 (TEFOR).

Footnotes

BD is a co-founder of WatchFrog™, all other authors have no conflicts of interests directly related to the material being published.

Author Contributions J.B.F., B.D. designed the study. J.B.F., B.M., S.L.M. and M.L. were involved in all experiments. P.S. helped carry out RT-qPCR and all bioinformatics analyses. MLet collected mobility data and performed analysis. P.A. and A.J. carried out CLARITY procedure. B.M. did brain reconstruction and cell counting. J.B.F., B.M. and B.D. analysed data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Bernal J. Thyroid hormones and brain development. Vitamins and hormones 71, 95–122, doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(05)71004-9 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop V. J. et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clinical endocrinology 50, 149–155 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyages S. C. & Halpern J. P. Endemic cretinism: toward a unifying hypothesis. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association 3, 59–69, doi: 10.1089/thy.1993.3.59 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korevaar T. I. et al. Association of maternal thyroid function during early pregnancy with offspring IQ and brain morphology in childhood: a population-based prospective cohort study. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology 4, 35–43, doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00327-7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morreale de Escobar G., Obregon M. J. & Escobar del Rey F. Role of thyroid hormone during early brain development. Europeanjournal of endocrinology/European Federation of Endocrine Societies 151 Suppl 3, U25–37 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff T. J., Zota A. R. & Schwartz J. M. Environmental chemicals in pregnant women in the United States: NHANES 2003–2004. Environmental health perspectives 119, 878–885, doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002727 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee D. Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation. Report No. 1725–9177, (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Crofton K. M. Thyroid disrupting chemicals: mechanisms and mixtures. International journal of andrology 31, 209–223, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00857.x (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boas M., Feldt-Rasmussen U., Skakkebaek N. E. & Main K. M. Environmental chemicals and thyroid function. European journal of endocrinology/European Federation of Endocrine Societies 154, 599–611, doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02128 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfosse V. et al. Synergistic activation of human pregnane X receptor by binary cocktails of pharmaceutical and environmental compounds. Nature communications 6, 8089, doi: 10.1038/ncomms9089 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelstad M. et al. Mixtures of endocrine-disrupting contaminants induce adverse developmental effects in preweaning rats. Reproduction 147, 489–501, doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0447 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini J. B. et al. An in vivo multiwell-based fluorescent screen for monitoring vertebrate thyroid hormone disruption. Environmental science & technology 41, 5908–5914 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlow J. D. & Brown D. D. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the regulation of a transcription factor gene by thyroid hormone during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Molecular endocrinology 13, 2076–2089, doi: 10.1210/mend.13.12.0383 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turque N., Palmier K., Le Mevel S., Alliot C. & Demeneix B. A. A rapid, physiologic protocol for testing transcriptional effects of thyroid-disrupting agents in premetamorphic Xenopus tadpoles. Environmental health perspectives 113, 1588–1593 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E., Rajapakse N. & Kortenkamp A. Something from “nothing”–eight weak estrogenic chemicals combined at concentrations below NOECs produce significant mixture effects. Environmental science & technology 36, 1751–1756 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop P. D. & Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin): a systematical and chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis. (Garland Pub., 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara A., Baker B. S. & Tata J. R. Developmental and regional expression of thyroid hormone receptor genes during Xenopus metamorphosis. Development 112, 933–943 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim W., Nguyen N. H., Yang H. Y., Scanlan T. S. & Furlow J. D. A thyroid hormone antagonist that inhibits thyroid hormone action in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277, 35664–35670, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205608200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereben B., McAninch E. A., Ribeiro M. O. & Bianco A. C. Scope and limitations of iodothyronine deiodinases in hypothyroidism. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 11, 642–652, doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.155 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois G. M. et al. Deiodinase activity is present in Xenopus laevis during early embryogenesis. Endocrinology 147, 4941–4949, doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0609 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka Y. & Smith J. C. Spatial and temporal patterns of cell division during early Xenopus embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 229, 307–318, doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0101 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. et al. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 497, 332–337, doi: 10.1038/nature12107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya F. et al. Live imaging of targeted cell ablation in Xenopus: a new model to study demyelination and repair. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 32, 12885–12895, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2252-12.2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen L. et al. Xenopus Bcl-X(L) selectively protects Rohon-Beard neurons from metamorphic degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 7869–7874, doi: 10.1073/pnas.141226798 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straka H. & Simmers J. Xenopus laevis: an ideal experimental model for studying the developmental dynamics of neural network assembly and sensory-motor computations. Developmental neurobiology 72, 649–663, doi: 10.1002/dneu.20965 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Global Chemicals Outlook: Towards Sound Management of Chemicals. (2012).

- Crofton K. M. et al. Thyroid-hormone-disrupting chemicals: evidence for dose-dependent additivity or synergism. Environmental health perspectives 113, 1549–1554 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizhanova A. & Kopp P. Minireview: The sodium-iodide symporter NIS and pendrin in iodide homeostasis of the thyroid. Endocrinology 150, 1084–1090, doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1437 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser T. J., Vanderdoestobe I., Docter R. & Hennemann G. Subcellular-Localization of a Rat-Liver Enzyme Converting Thyroxine into Tri-Iodothyronine and Possible Involvement of Essential Thiol-Groups. Biochem J 157, 479–482 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer U. & Steegborn C. New insights into the structure and mechanism of iodothyronine deiodinases. Journal of molecular endocrinology 55, R37–R52, doi: 10.1530/Jme-15-0156 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini J. B. et al. Thyroid hormone signaling in the Xenopus laevis embryo is functional and susceptible to endocrine disruption. Endocrinology 153, 5068–5081, doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1463 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelouahab N. et al. Maternal and cord-blood thyroid hormone levels and exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polychlorinated biphenyls during early pregnancy. American journal of epidemiology 178, 701–713, doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt141 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P. et al. Effects of PCBs and PBDEs on thyroid hormone, lymphocyte proliferation, hematology and kidney injury markers in residents of an e-waste dismantling area in Zhejiang, China. The Science of the total environment 536, 215–222, doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.025 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duntas L. H. & Stathatos N. Toxic chemicals and thyroid function: hard facts and lateral thinking. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders 16, 311–318, doi: 10.1007/s11154-016-9331-x (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preau L., Le Blay K., Saint Paul E., Morvan-Dubois G. & Demeneix B. A. Differential thyroid hormone sensitivity of fast cycling progenitors in the neurogenic niches of tadpoles and juvenile frogs. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 420, 138–151, doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.11.026 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson J. L. & Altman J. The effects of early hypo- and hyperthyroidism on the development of the rat cerebellar cortex. II. Synaptogenesis in the molecular layer. Brain research 44, 25–36 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Juarez A. et al. Thyroid Hormone Signaling Acts as a Neurogenic Switch by Repressing Sox2 in the Adult Neural Stem Cell Niche. Cell Stem Cell 10, 531–543, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.008 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M. et al. DNA methylation of BDNF as a biomarker of early-life adversity. P Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 6807–6813, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408355111 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickl-Jockschat T. & Michel T. M. The role of neurotrophic factors in autism. Molecular psychiatry 16, 478–490, doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.103 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida L. E. F., Roby C. D. & Krueger B. K. Increased BDNF expression in fetal brain in the valproic acid model of autism. Mol Cell Neurosci 59, 57–62, doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2014.01.007 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadakata T. et al. Reduced axonal localization of a Caps2 splice variant impairs axonal release of BDNF and causes autistic-like behavior in mice. P Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 21104–21109, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210055109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini J. B. et al. Parallel Biotransformation of Tetrabromobisphenol A in Xenopus laevis and Mammals: Xenopus as a Model for Endocrine Perturbation Studies. Toxicological Sciences 125, 359–367, doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr312 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegiel J. et al. Neuronal nucleus and cytoplasm volume deficit in children with autism and volume increase in adolescents and adults. Acta neuropathologica communications 3, 2, doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0183-5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooten I. A. et al. Neurons in the fusiform gyrus are fewer and smaller in autism. Brain : a journal of neurology 131, 987–999, doi: 10.1093/brain/awn033 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman G. C. et al. Association of Gestational Maternal Hypothyroxinemia and Increased Autism Risk. Ann Neurol 74, 733–742, doi: 10.1002/ana.23976 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman G. C. Autism: transient in utero hypothyroxinemia related to maternal flavonoid ingestion during pregnancy and to other environmental antithyroid agents. Journal of the neurological sciences 262, 15–26, doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.023 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen A. et al. Urinary phthalates from 168 girls and boys measured twice a year during a 5-year period: associations with adrenal androgen levels and puberty. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 98, 3755–3764, doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1284 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns L. E. et al. Urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to maternal serum thyroid and sex hormone levels during pregnancy: a longitudinal analysis. Reproductive biology and endocrinology: RB&E 13, 4, doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-13-4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J. L. & Jacobson S. W. Intellectual impairment in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls in utero. New Engl J Med 335, 783–789, doi: 10.1056/Nejm199609123351104 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubig P. A., Aguiar A. & Schantz S. L. Lead and PCBs as Risk Factors for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Environmental health perspectives 118, 1654–1667, doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901852 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. C. et al. Relationship between Environmental Phthalate Exposure and the Intelligence of School-Age Children. Environmental health perspectives 118, 1027–1032, doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901376 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa C. et al. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and autism spectrum disorders. Asn Neuro 4, 223–229, doi: ARTN e0008910.1042/AN20120015 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippat C. et al. Phthalate concentrations in house dust in relation to autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay in the CHildhood Autism Risks from Genetics and the Environment (CHARGE) study. Environ Health-Glob 14, doi: ARTN 5610.1186/s12940-015-0024-9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. N. et al. Maternal Perchlorate Levels in Women With Borderline Thyroid Function During Pregnancy and the Cognitive Development of Their Offspring: Data From the Controlled Antenatal Thyroid Study. J Clin Endocr Metab 99, 4291–4298, doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1901 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbstman J. B. et al. Prenatal Exposure to PBDEs and Neurodevelopment. Environmental health perspectives 118, 712–719, doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901340 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh L. et al. Chasing the Elusive Benzofuran Impurity of the THR Antagonist NH-3: Synthesis, Isotope Labeling, and Biological Activity. J Org Chem 81, 1870–1876, doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02665 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods 25, 402–408, doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp J. R. et al. Optimization of CLARITY for Clearing Whole-Brain and Other Intact Organs(1,2,3). eNeuro 2, doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0022-15.2015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.