Abstract

Purpose:

To assess the respective involvement of retina versus choroid in presumed ocular tuberculosis (POT) in a non-endemic area using dual fluorescein (FA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA).

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed cases diagnosed with POT at the Centre for Ophthalmic Specialized Care, Lausanne, Switzerland. Angiography signs were quantified using an established dual FA and ICGA scoring system for uveitis.

Results:

Out of 1739 uveitis patients visited from 1995 to 2014, 53 (3%) were diagnosed with POT; of whom 28 patients (54 eyes) had sufficient data available to be included in this study. Of 54 affected eyes, 39 showed predominant choroidal involvement, 14 showed predominant retinal involvement and one had equal retinal and choroidal scores. Mean angiographic score was 6.97 ± 5.08 for the retina versus 13.48 ± 7.06 for the choroid (P < 0.0001). For patients with sufficient angiographic follow-up after combined anti-tuberculous and inflammation suppressive therapy, mean FA and ICGA scores decreased from 6.97 ± 5.08 to 3.63 ± 3.14 (P = 0.004), and 13.48 ± 7.06 to 7.47 ± 5.58 (P < 0.0001), respectively.

Conclusion:

These results represent the first report of the respective contributions of retinal and choroidal involvement in POT. Choroidal involvement was more common, for which ICGA is the preferred examination. In cases of compatible uveitis with positive results of an interferon-gamma release assay, particularly in a region that is non-endemic for TB, dual FA and ICGA should be performed to help establish the diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis and improve follow-up.

Keywords: Angiographic Score, Chorioretinitis, Fluorescein Angiography, Indocyanine Green Angiography, Ocular Tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) represents a major public health problem, with 9.6 million new cases diagnosed worldwide in 2014.[1] While TB most commonly affects pulmonary structures, extra-pulmonary involvement is reported in 20–40% of cases.[2] In a minority of cases with extra-pulmonary involvement, TB involves structures of the eye.[3,4] Within endemic areas, such as India,[5] ocular tuberculosis typically presents in the active infectious form. On the other hand, in non-endemic areas—such as Switzerland, which has only an estimated 550 new cases per year[6]—patients with ocular tuberculosis tend to present a subacute or indolent type of inflammation thought to be caused by an immunologic reaction against Mycobacterium tuberculosis[7] or other mycobacteria[8] rather than by the infection itself.[9,10,11,12] This immune reaction develops against mycobacterial antigens present in tissues, such as the pigment epithelium, which is a sanctuary in which antigens concentrate.[13] Since ocular tuberculosis is rare in non-endemic areas and because its clinical features are not pathognomonic, diagnosis is easily missed or substantially delayed.[3]

In recent years, new diagnostic modalities have become available to the uveitis specialist contributing to improvement in the diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis. In addition to the Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) or Mantoux test, interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) is an important progress. Negative IGRA result excludes tuberculosis, but a positive result prompts the clinician to verify whether there is an active ocular tuberculosis by determining if there is ongoing disease characterized by a compatible uveitis including fundus foci, fundus scars, retinal vasculitis and papillitis or the result is indicative of only a latent inactive prior contact with M. tuberculosis or other mycobacteria. Our ability to detect previously subclinical and occult choroiditis has been substantially increased by newly available procedures for investigating the posterior segment of the eye,[14,15,16] including choroidal optical coherence tomography (OCT)[17] and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA).[7,18,19,20,21,22,23] These advancements may lead to substantial increase in the sensitivity of ocular tuberculosis diagnosis.

Prior studies have reported the use of clinical fundus examination and fluorescein angiography (FA) to describe retinal involvement in ocular tuberculosis.[24] However, these studies could not determine choroidal involvement or the proportion of retinal versus choroidal disease, as no reliable method was available to assess choroiditis. This is now possible with the use of ICGA. Thus, in our present study, we aimed to determine the degree of angiographic retinal involvement using FA, and the amount of choroidal involvement by ICGA, as well as the proportion of each versus the other.

METHODS

For this study, we reviewed the charts of patients seen at the uveitis clinic in the Centre for Ophthalmic Specialized Care (COS), Lausanne, Switzerland between 1995 and 2014. We identified and retrospectively examined the files of patients diagnosed with presumed ocular tuberculosis. We excluded cases of serpiginoid choroiditis associated with a positive IGRA test, which is considered a phenotypically different entity with a diverse physiopathology.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Ocular tuberculosis was diagnosed in cases showing a compatible clinical presentation including fundus foci, fundus scars, retinal vasculitis and papillitis, together with a positive IGRA test and/or a hyper-positive (>15 mm induration) PPD skin test using a Mantoux test with 2 units tuberculin. The study included patients presenting with tuberculous chorioretinitis for whom results of dual FA/ICGA angiographic were available. In these patients, follow-up data after treatment completion were analyzed. Standard anti-tuberculous treatment (ATT) for ocular tuberculosis comprised four-drug therapy for two months, three-drug therapy for four months, and two-drug therapy for six months.

Clinical Work-up

All included patients underwent the complete routine work-up for patients with uveitis. Each major visit included a complete ocular examination (Snellen visual acuity, slit-lamp examination, applanation tonometry, and funduscopy with mydriasis) as well as laser flare photometry (LFP), computerized visual field (VF) testing, optical coherence tomography (OCT) once available, and dual FA and ICGA.

Laser Flare Photometry, Optical Coherence Tomography, and Visual Field Testing

Laser flare photometry was performed using a Kowa FM-500 or Kowa FM-700 (Kowa Company, Ltd., Electronics and Optics Division, Tokyo, Japan). OCT was performed using an OTI-Spectral OCT/SLO (OTI Inc., Toronto, Canada) or Heidelberg Spectralis OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Inc., Heidelberg, Germany). For VF assessment, we used the G1 program of the Octopus 900, G Standard (Haag-Streit, Bern, Switzerland).

Angiography

FA and ICGA were performed using a previously described standard protocol.[25] Briefly, FA and ICGA were usually performed simultaneously. Images were acquired using a Topcon 50 IA camera (Tokyo, Japan) coupled to an ImageNet (Topcon) image digitalizing system or a Heidelberg Retina Angiograph HRA 2 (Heidelberg Engineering, Inc., Heidelberg, Germany). To exclude autofluorescence, pre-injection fluorescence was determined with the highest flash intensity used for ICGA. At the same time, we acquired red-free posterior pole frames.

We performed a bolus injection of 4 mg of indocyanine green (ICG) (Cardiogreen; Peaselt, Lorei, Germany) diluted in 5 ml of an aqueous solution, and then ICGA frames of the posterior pole were acquired over approximately 2–3 minutes (early-phase angiogram). At 12 ± 3 minutes after ICG injection (intermediate-phase ICGA angiogram) frames of the posterior pole, and a minimum of eight frames from the whole periphery over 360° were acquired for detailed analysis. At the end of the ICGA intermediate phase, we performed fluorescein angiography. For up to 2 minutes, we took early fluorescein angiographic frames of the posterior pole. Between 4 to 7 minutes, we performed 360° panorama imaging of the periphery (minimum of eight frames), and at 10 minutes we acquired late fluorescein posterior pole frames. At 24 ± 4 minutes after ICG injection, we captured the late ICG fluorescence pattern (late-phase ICGA angiogram) in the same manner as in the intermediate phase.

Angiographic Score

FA and ICGA were evaluated using an established dual FA/ICGA scoring system slightly modified for granulomatous chorioretinitis.[26,27] Briefly, a total maximum score of 40 was assigned to eight FA items including: (1) Optic disc hyperfluorescence (maximal score [MS] = 3), (2) macular edema (MS = 4), (3) retinal vascular staining and/or leakage (MS = 7), (4) capillary leakage (MS = 10), (5) retinal capillary nonperfusion (MS = 6), (6) optic disc neovascularization (MS = 2)/neovascularization elsewhere (MS = 2), (7) pinpoint leaks at the posterior pole (MS = 2), (8) retinal staining and/or subretinal pooling (MS = 4). A total maximum score of 40 was also assigned to four ICGA signs including: (1) Early stromal vessel hyperfluorescence (MS = 3), (2) fuzziness/exudation of choroidal vessels (MS = 6), (3) hypofluorescent dark dots or areas (excluding atrophy) (MS = 8), (4) optic disc hyperfluorescence and/or peripheral hyperfluorescent pinpoints (MS = 3). Each of the four ICGA items counted double versus the eight FA items to ensure that the scores reflected equivalent importance of involvement in both the retinal and choroidal compartments.

Angiographic data were analysed by an experienced angiographic specialist (CPH) in a masked fashion, names of patients being hidden to the examiner.

Outcome Measures

We calculated the mean patient age, mean time to diagnosis, mean duration of TB treatment, and the proportion of presumed ocular tuberculosis patients relative to the whole collective of uveitis patients. We determined the average angiographic score before and after anti-tuberculous treatment, as well as best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP), laser flare photometry (LFP), and the FA and ICGA scores for all eyes. We determined the number of cases with a predominance of retinal involvement versus choroidal involvement, and vice versa. Finally, we calculated the number of cases with occult chorioretinal lesions visible only on ICGA or FA. Comparisons were made using paired t-test.

The study was approved by the IRB, and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required and no funding was received for this research.

RESULTS

A total of 1739 patients with uveitis were seen at the Centre for Ophthalmic Specialized Care (COS) from 1995 to 2014. Among these cases, we identified 53 (3%) charts with the diagnosis of presumed ocular tuberculosis. Out of these 53 subjects, 28 patients (54 eyes) with chorioretinitis fulfilled the inclusion criteria for our study. In two patients, only one eye could be evaluated. Patients included 12 female and 16 male subjects, with a mean age of 45.43 ± 17.03 years. Mean diagnostic delay (time interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis) was 58.39 ± 80.33 months, with a median of 24 months. Mean duration of treatment was 10.28 ± 4.16 months.

Mean BCVA was 0.82 ± 0.39 (Snellen VA) at presentation, increasing to 0.95 ± 0.36 after treatment (P = 0.0002, paired t-test). Mean IOP was well within the normal range before (14.7 mmHg) and after treatment (14.6 mmHg) (P = 0.3, NS). Intraocular inflammation measured with laser flare photometry showed a mean flare of 27.06 ± 29 (ph/ms) at presentation, which decreased to 22.09 ± 32.03 after treatment (P = 0.1, NS). Fifteen patients presented with an anterior granulomatous uveitis showing granulomatous keratic precipitates and/or Koeppe nodules, while thirteen patients had a non-granulomatous uveitis.

Fundus Examination

Fundus examination revealed no choroidal fundus foci in 8 patients (2 of whom had severe papillitis), active choroidal foci in 15 cases, and a mixture of choroidal scars and active foci in 4 subjects. One case exhibited an isolated tuberculoma. Five patients showed pronounced papillitis; as an isolated fundus finding in two subjects and in association with fundus foci in three cases. Isolated papillitis was associated with occult choroidal involvement seen on ICGA in both cases, explaining the origin of the papillitis. All patients had some degree of vitritis. Clinical vasculitis was present in 14 patients being bilateral in two. Vasculitis was proliferative in four cases and one patient had disc neovessels.

Angiographic Findings

The type of angiographic device used did not influence the results. The most frequent FA sign (optic disc hyperfluorescence) and the most frequent ICGA sign (fuzziness/exudation of choroidal vessels) were compared between the Topcon and Heidelberg devices, showing no statistical difference, indicating that there was no bias whether one or the other instrument was used.

Dual FA/ICGA angiographic scoring enabled us to establish the proportion of retinal versus choroidal involvement. Mean of FA and ICGA scores of both eyes were calculated for each patient and the mean FA and ICGA scores were compared in each patient: In 19 patients, the ICGA score was higher than the FA score, in 8 patients the FA score was higher than the ICGA score and in one patient FA and ICGA scores were equal.

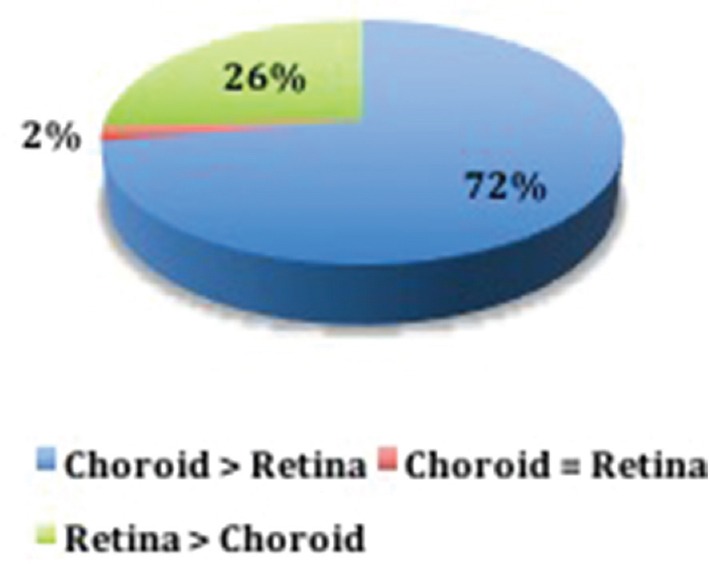

Considering all 54 examined eyes, 39 (72%) had predominant choroidal lesions, 14 (26%) had preponderant retinal lesions, and one (2%) had equal retinal and choroidal scores [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of eyes (N = 54) according to preponderant involvement: choroid > retina; retina > choroid; or retina = choroid.

In four (14%) patients, diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis would have been missed if only FA had been performed, as the FA score was less than three (background inflammation), while the ICGA scores of these patients were 9, 13, 14, and 15. On the other hand, two (7%) patients would not have been diagnosed properly if only ICGA had been performed, as they had ICGA scores of less than three, while their FA scores were 13 and 9.

With regard to mean angiographic scores, choroidal involvement was significantly more important than retinal involvement [13.48 ± 7.06 versus 6.97 ± 5.08 (P < 0.0001)] [Figure 2].

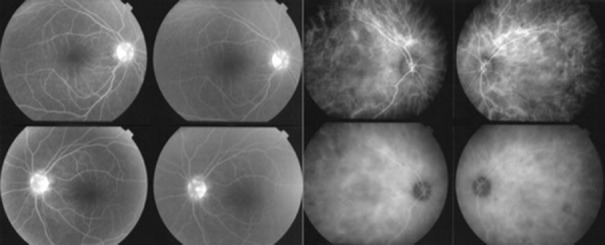

Figure 2.

Example of discrepancy between choroidal and retinal involvement, with simultaneously acquired frames showing quasi-absent retinal involvement (background inflammation score of 3/40) and severe choroidal involvement with an indocyanine green angiography score of 22/40.

FA revealed that the preponderant lesions in the 54 analyzed eyes were disc hyperfluorescence (N = 48, 89%) [Figure 3], peripheral capillary leakage at 5–10 minutes (N = 37, 69%), macular hyperfluorescence (N = 31, 57%), and posterior pole capillary leakage at 5–10 minutes (N = 30, 56%) [Figure 4]. Eighteen (33%) eyes showed peripheral retinal vascular staining and/or leakage. Eleven (20%) eyes showed retinal vascular staining and/or leakage at and around posterior pole arcades at 5–10 minutes [Figure 4]. Retinal capillary non-perfusion was observed in 7 (13%) eyes, and neovascularization elsewhere (NVE) in 7 (13%) eyes [Figure 5]. Rare features included retinal staining and/or subretinal pooling at 5–10 minutes (N = 1, 2%) and neovascularization of the optic disc (NVD) (N = 1, 2%). Figure 6 shows the distribution of FA lesions.

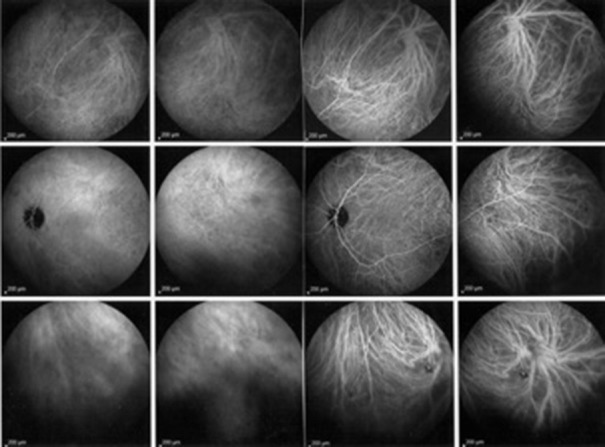

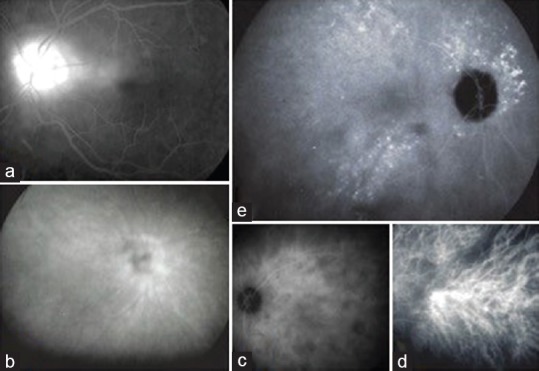

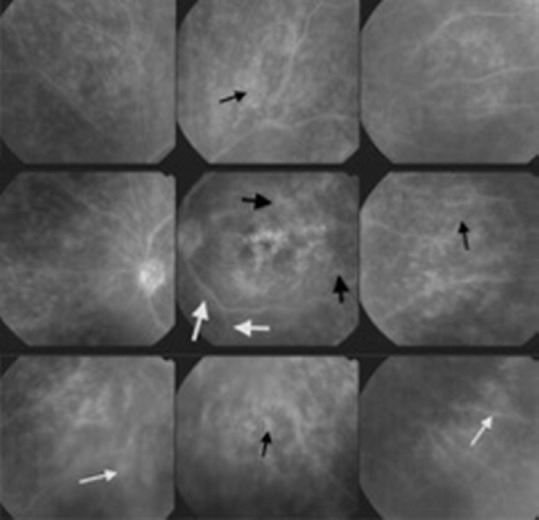

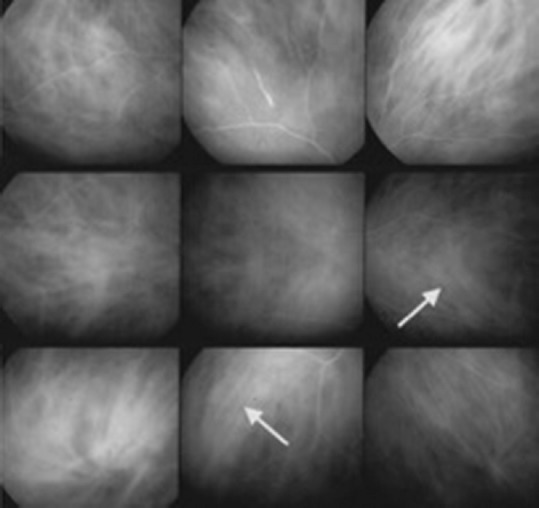

Figure 3.

(a) Fluorescein angiography showing disc hyperfluorescence (optic disc score of 3/3). (b) ICGA showing hyperfluorescence of the optic disc (score of 3/3). (c) ICGA showing posterior pole dark dots (score of 2/2). (d) ICGA showing early stromal hyperfluorescence at the posterior pole (score of 1/1). (e) ICGA showing hyperfluorescent pinpoints (score of 3/3). ICGA, indocyanine green angiography.

Figure 4.

Fluorescein angiography showing macular hyperfluorescence (score of 4/4), capillary leakage in the periphery (small black arrows; score of 8/8) and at the posterior pole (large black arrows; score of 2/2). There is also detectable retinal vascular staining and leakage in the periphery (small white arrows; score of 4/4) and at the posterior pole (large white arrows; score of 1/3).

Figure 5.

Fluorescein angiography showing NVE (score of 2/2) and retinal capillary non-perfusion (score of 4/6). NVE, neovascularization elsewhere.

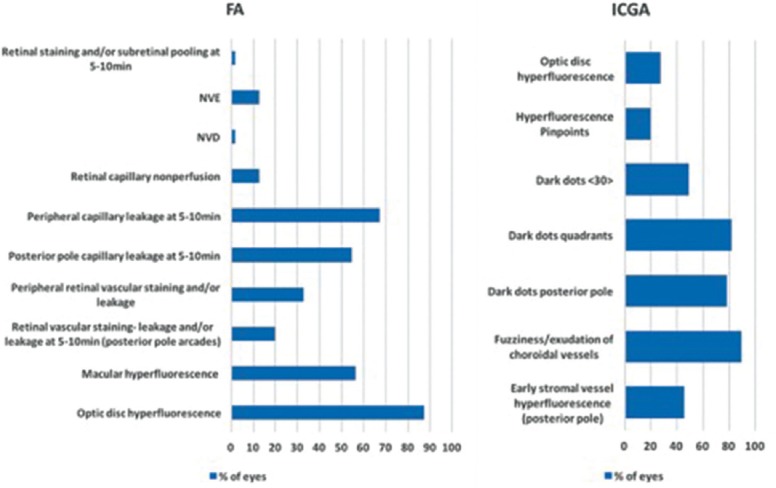

Figure 6.

Left: Distribution of lesions seen on FA before anti-tuberculous treatment. Right: Distribution of lesions seen on ICGA before anti-tuberculous treatment. FA, fluorescein angiography; ICGA, indocyanine green angiography; NVD, neovascularization of the optic disc; NVE, neovascularization elsewhere.

ICGA results of the 54 eyes revealed that the most frequent lesions were fuzziness/exudation of choroidal vessels (N = 49, 91%) [Figure 7]; hypofluorescent dark dots (HDDs) in the mid-periphery and periphery, evaluated in four quadrants (N = 45, 83%) [Figure 5]; and HDDs at the posterior pole (N = 43, 80%) [Figure 3]. In each 27 (50%) eyes, we detected more than 30 HDDs. Early stromal vessel hyperfluorescence at the posterior pole was observed in 25 (46%) eyes [Figure 3], optic disc hyperfluorescence in 15 (28%) eyes [Figure 3], and hyperfluorescent peripheral pinpoints in 11 (20%) eyes [Figure 3]. Figure 6 shows the distribution of ICGA lesions.

Figure 7.

Indocyanine green angiography showing fuzzy vessels on more than two quadrants (arrows), although the vessel courses are still recognizable (score of 3/6). Dark dots in the periphery are also detectable (score of 6/6).

Notably, in most instances, retinal and choroidal lesions occurred independently of each other—i.e., a retinal FA lesion did not correspond to a choroidal ICGA lesion and vice versa. This indicated dual random independent involvement of the retina and choroid. We further analyzed the evolution of the FA/ICGA scores.

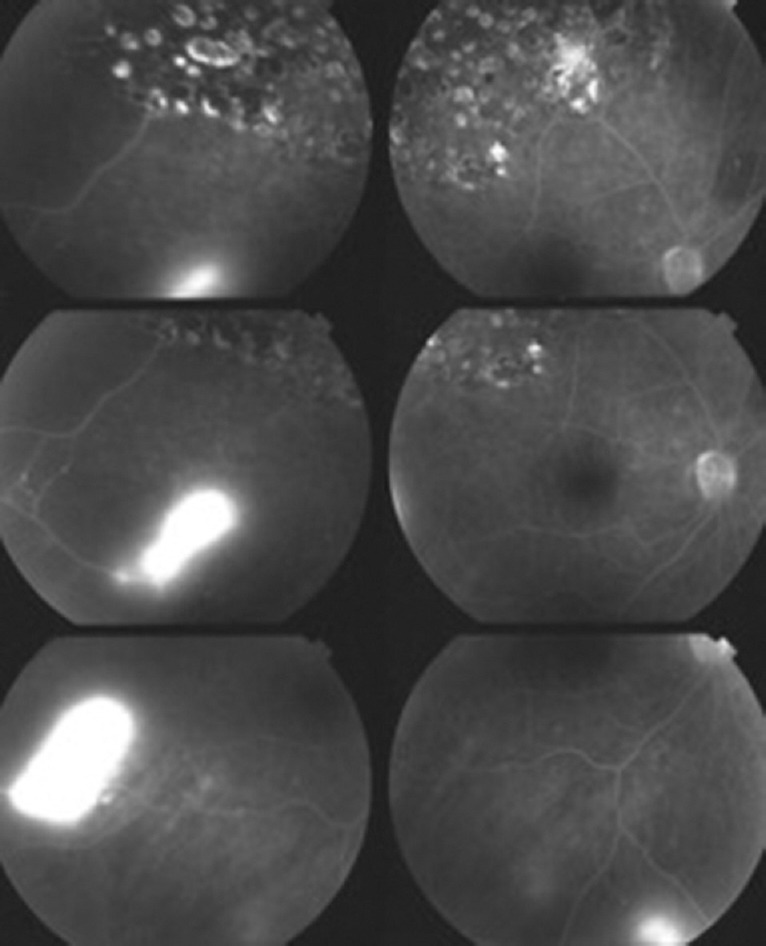

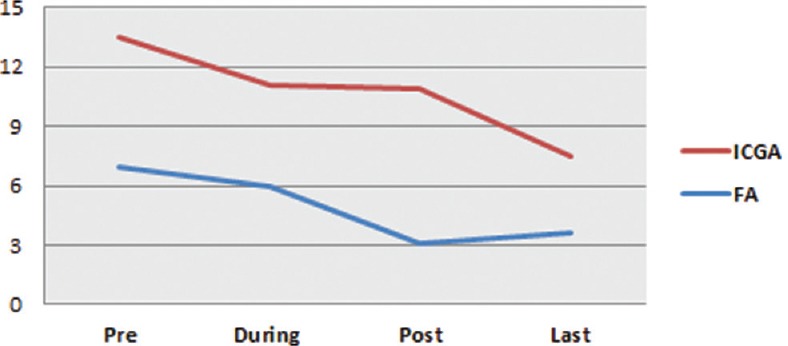

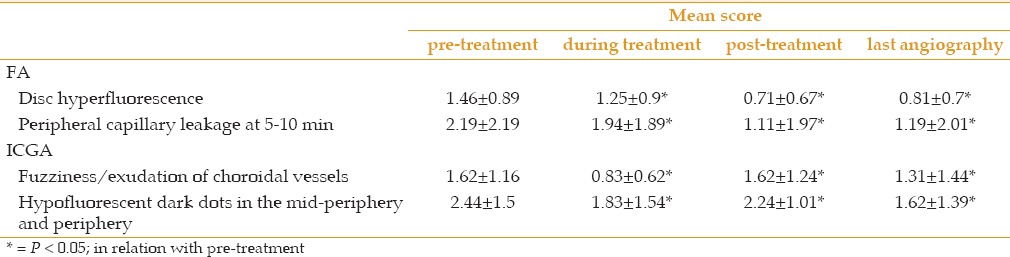

Before and after treatment, the mean FA score changed from 6.97±5.08 to 3.63±3.14 (P = 0.004) and the mean ICGA score decreased from 13.48±7.06 to 7.47±5.58 (P < 0.0001) [Figure 8, 9 and Table 1]. Figure 9 shows also the evolution of the angiographic scores and Table 1 shows the evolution of individual angiographic signs. Post-treatment angiography was obtained at a mean follow-up time of 9.2 ± 5.39 months and final follow-up angiography was obtained after a mean follow-up of 23 ± 23.11 months. In 2 out of 28 patients ATT had to be stopped early after 5 and 6 months due to gastrointestinal disturbance and a general ill-feeling. Despite discontinuing of ATT, no recurrence was noted.

Figure 8.

Improvement of the lesions on indocyanine green angiography after anti-tuberculous treatment. Choroidal vessels were barely recognizable before treatment (left sextet of frames), and became more distinct after therapy (right sextet of frames).

Figure 9.

Evolution of angiographic scores before treatment, during treatment, after treatment, and at the last follow-up.

Table 1.

Pre-treatment, during-treatment, post-treatment and last-treatment scores of the 2 most frequent fluorescein angiographic (FA) and indocyanine green angiographic (ICGA) signs (* = P < 0.05; in relation with pre-treatment)

DISCUSSION

Ocular tuberculosis represents a substantial diagnostic challenge in areas that are non-endemic for TB.[28,29] While testing for infectious agents often yields positive results in more endemic areas, the diagnostic elements and criteria in non-endemic areas remain unsatisfactory. In non-endemic regions, ocular lesion severity is often less pronounced as evidenced in our series where no fundus lesions were observed in five of the 28 patients. Thus, there remains a need to improve our diagnostic abilities by integrating new diagnostic modalities, such as interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs).[30,31,32,33,34,35,36]

Our present results showed that tuberculous chorioretinitis could involve retinal and choroidal structures independently, such that lesions in one compartment were not necessarily the consequence of lesions from the other compartment. These findings indicate that ocular tuberculosis can involve all eye structures at random, as casualties of a systemic disease.[4,9,37] This is in contrast to Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, in which the inflammation is exclusively generated within the choroidal stroma, and lesions in the other structures result from spill-over of choroidal inflammation.[38,39]

The presently applied dual FA/ICGA scoring system also revealed that choroiditis was predominant over retinitis with regard to both intensity (ICGA scores were almost double the FA scores) and proportion of cases (two-thirds of examined eyes showed greater choroidal involvement). This indicates that investigations relying on FA alone without ICGA may underestimate ocular involvement, potentially leading to misdiagnosis. Indeed, twice as many patients would have been misdiagnosed if they have been examined with FA alone as compared to with ICGA alone. Our findings suggest that if only one type of angiography is to be performed, ICGA is more rewarding.

In the absence of any better quantitative measurement of retinal and choroidal inflammation, it is reasonable to consider dual FA/ICGA scoring as a reliable marker.

We further determined details regarding individual lesion types and their frequency in this pathology. We found that fuzziness/exudation of choroidal vessels was the most frequent ICGA feature, followed by HDDs in the quadrants and posterior pole, and early vessel hyperfluorescence in the posterior pole. These signs were all present in more than two-thirds of cases. On the other hand, FA results revealed hyperfluorescence of the optic disc, macular hyperfluorescence, and capillary leakage in the periphery in over three-fourths of cases.

Identification of such dual angiographic features in a patient will lead the clinician to suspect tuberculous chorioretinitis, prompting the performance of investigational tests (e.g., PPD and/or IGRA) the results of which may suggest a diagnosis of presumed ocular tuberculosis. Furthermore, dual FA/ICGA can provide global information on the chorioretinal inflammation at each time-point. We found that the FA and ICGA scores each decreased with treatment. Overall, dual FA/ICGA appraisal appears to provide the best global information, and likely represents the best modality for reaching a diagnosis and performing follow-up of this pathology.

In conclusion, our present results are the first report of the respective contributions of retina and choroid in POT. We found preferential involvement of the choroid for which ICGA is the examination of choice. In cases of compatible uveitis with positive results of an IGRA test, particularly in a region that is non-endemic for TB, dual FA and ICGA should be performed to help establish the diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis and improve follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers' bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented as a free paper at the European Association for Vision and Eye Research (EVER) congress 2015 in Nice, France, on October 10.

REFERENCES

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2014. [Internet] WHO. [updated in 2014, cited 2015 Jul 2]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- 2.Mazza-Stalder J, Nicod L, Janssens JP. [Extrapulmonary tuberculosis] Rev Mal Respir. 2012;29:566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cimino L, Herbort CP, Aldigeri R, Salvarani C, Boiardi L. Tuberculous uveitis, a resurgent and underdiagnosed disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta V, Shoughy SS, Mahajan S, Khairallah M, Rosenbaum JT, Curi A, et al. Clinics of ocular tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015;23:14–24. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2014.986582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta A, Bansal R, Gupta V, Sharma A, Bambery P. Ocular signs predictive of tubercular uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuberculose [Internet] Berne: Office fédéral de la santé publique; [updated in 2015, cited 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/medizin/00682/00684/01108/index.html?lang=fr . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodaghi B, LeHoang P. Ocular tuberculosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:443–448. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200012000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuznetcova TI, Sauty A, Herbort CP. Uveitis with occult choroiditis due to Mycobacterium kansasii: Limitations of interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) tests (case report and mini-review on ocular non-tuberculous mycobacteria and IGRA cross-reactivity) Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s10792-012-9588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.La Distia Nora R, van Velthoven MEJ, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, et al. Clinical manifestations of patients with intraocular inflammation and positive QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube test in a country nonendemic for tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:754–761. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Bambery P, Arora SK. Role of Anti-Tubercular Therapy in Uveitis With Latent/Manifest Tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:772–9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tufariello JM, Chan J, Flynn JL. Latent tuberculosis: Mechanisms of host and bacillus that contribute to persistent infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:578–590. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, Bambery P, Dogra MR, Agarwal A. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis: Clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao NA, Saraswathy S, Smith RE. Tuberculous uveitis: Distribution of mycobacterium tuberculosis in the retinal pigment epithelium. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1777–1779. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciardella AP, Borodoker N, Costa DL, Huang SJ, Cunningham ET, Slakter JS. Imaging the posterior segment in uveitis. Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;15:281–296. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciardella AP, Prall FR, Borodoker N, Cunningham ET. Imaging techniques for posterior uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:519–30. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000144386.05116.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finamor LP, Muccioli C, Belfort R. Imaging techniques in the diagnosis and management of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45:31–40. doi: 10.1097/01.iio.0000155937.05955.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Mezaine HS, Al-Muammar A, Kangave D, Abu El-Asrar AM. Clinical and optical coherence tomographic findings and outcome of treatment in patients with presumed tuberculous uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2008;28:413–423. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abouammoh M, Abu El-Asrar AM. Imaging in the Diagnosis and Management of Ocular Tuberculosis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2012;52:97–112. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318265d5a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu El-Asrar AM, Abouammoh M, Al-Mezaine HS. Tuberculous Uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:19–39. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181d2ccb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tayanc E, Akova Y, Yilmaz G. Indocyanine green angiography in ocular tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2004;12:317–322. doi: 10.1080/092739490500336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfensberger TJ, Piguet B, Herbort CP. Indocyanine green angiographic features in tuberculous chorioretinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:350–353. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papadia M, Herbort CP. Unilateral papillitis, the tip of the iceberg of bilateral ICGA-detected tuberculous choroiditis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19:124–126. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.530872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Luigi G, Mantovani A, Papadia M, Herbort CP. Tuberculosis-related choriocapillaritis (multifocal-serpiginous choroiditis): Follow-up and precise monitoring of therapy by indocyanine green angiography. Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32:55–60. doi: 10.1007/s10792-011-9508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis--an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:561–587. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbort CP, LeHoang P, Guex-Crosier Y. Schematic interpretation of indocyanine green angiography in posterior uveitis using a standard angiographic protocol. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:432–440. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)93024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tugal-Tutkun I, Herbort CP, Khairallah M. Angiography Scoring for Uveitis Working Group (ASUWOG). Scoring of dual fluorescein and ICG inflammatory angiographic signs for the grading of posterior segment inflammation (dual fluorescein and ICG angiographic scoring system for uveitis) Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:539–552. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tugal-Tutkun I, Herbort CP, Khairallah M, Mantovani A. Interobserver agreement in scoring of dual fluorescein and ICG inflammatory angiographic signs for the grading of posterior segment inflammation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:385–389. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.489730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lou SM, Montgomery PA, Larkin KL, Winthrop K, Zierhut M, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment for Ocular Tuberculosis among Uveitis Specialists: The International Perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015;23:32–39. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2014.994784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vos AG, Wassenberg MWM, de Hoog J, Oosterheert JJ. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculous uveitis in a low endemic setting. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuberculosis (Guidance and guidelines) [Internet] England: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); [updated in May 2016, cited 2016 June 5]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg117 . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang M, Htoon HM, Chee SP. Diagnosis of tuberculous uveitis: Clinical application of an interferon-gamma release assay. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Updated Guidelines for Using Interferon Gamma Release Assays to Detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection [Internet] United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); [updated in 2010, cited 2015 July 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5905a1.htm?s_cid=rr5905a1_e . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahn SJ, Kim KE, Woo SJ, Park KH. The usefulness of interferon-gamma release assay for diagnosis of tuberculosis-related uveitis in Korea. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014;28:226–233. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2014.28.3.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ang M, Wong WL, Li X, Chee SP. Interferon γ release assay for the diagnosis of uveitis associated with tuberculosis: A Bayesian evaluation in the absence of a gold standard. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:1062–1067. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itty S, Bakri SJ, Pulido JS, Herman DC, Faia LJ, Tufty GT, et al. Initial results of QuantiFERON-TB Gold testing in patients with uveitis. Eye. 2009;23:904–909. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wrighton-Smith P, Zellweger J-P. Direct costs of three models for the screening of latent tuberculosis infection. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:45–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00005906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthew J, Thompson DMA. Ocular tuberculosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:844–849. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouchenaki N, Herbort C. Essentials in Ophthalmology: Uveitis and Immunological Disorders. In: Pleyer U, Mondino B, editors. Essentials in Ophthalmology: Uveitis and Immunological Disorders. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2004. pp. 234–253. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawaguchi T, Horie S, Bouchenaki N, Ohno-Matsui K, Mochizuki M, Herbort CP. Suboptimal therapy controls clinically apparent disease but not subclinical progression of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]