Abstract

Purpose

To use spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) to investigate risk factors predictive for development of atrophy of drusenoid lesions (drusen and drusenoid pigment epithelium detachment) in eyes with non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration (NNVAMD).

Design

Cohort study.

Participants

Forty-one eyes from 29 patients with NNVAMD.

Methods

Patients with NNVAMD who underwent registered SD-OCT imaging over a minimum period of six months, were reviewed. Drusenoid lesions that accompanied by new atrophy onset at 6 month or last follow up were further analyzed. Detailed lesion change was described throughout the study period. Odds ratios (OR) and risk for new local atrophy onset were calculated.

Main Outcomes Measures

Drusenoid lesion features and longitudinal changes in features including maximum lesion height, lesion diameter, lesion internal reflectivity, presence and extent of overlying intraretinal hyperreflective features (HRF). Subfoveal choroidal thickness and choroidal thickness measured below each lesion.

Results

543 individual drusenoid lesions were identified at baseline, while 28 lesions developed during follow-up. The mean follow-up time was 21.3 ± 8.6 (range, 6-44) months. 3.2% (18/571) of drusenoid lesions progressed to atrophy within 18.3±9.5 (range: 5-28) months of initial visit. Drusenoid lesions with heterogenous internal reflectivity were significantly associated with new atrophy onset at 6 month (OR=5.614, 95% confidence interval (CI) =1.277-24.673) and new atrophy onset at last follow up (OR=7.005, CI=2.300-21.337). Lesions with presence of HRF also were significant predictors for new atrophy onset at 6 month (OR=30.161, CI=4.766-190.860) and at last follow up (OR=11.211, CI=2.513-50.019). Lesions with a baseline maximum height over 80 microns or choroidal thickness less than 135 microns showed positive association with the new atrophy onset at last follow up (OR=7.886, CI=2.105-29.538 and OR=3.796, CI=1.154-12.481, respectively).

Conclusions

In this study, the presence of HRF overlying drusenoid lesions, a heterogeneous internal reflectivity of these lesions, was found consistently to be predictive of local atrophy onset in the ensuing months. These findings provide further insight into the natural history of anatomical change occurring in patients with NNVAMD.

Keywords: Pigment epithelium detachment, Optical Coherence Tomography, Drusen

Introduction

Macular drusen, particularly large drusen, are a hallmark feature of age-related macular degeneration (AMD)1. A number of large epidemiologic studies have identified that the presence of large drusen, and a larger overall area of macular drusen, as well as retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) alterations, are clinically important risk factors for the development of advanced AMD, defined as the central geographic atrophy (GA) or choroidal neovascularization (CNV)2–5. More recently, from the Age Related Eye Diseases Study (AREDS), Cukras and coworkers6 demonstrated that particularly large and confluent drusenoid lesions, termed drusenoid pigment epithelial detachments (DPEDs), conferred an especially high risk for progression to advanced AMD, with 19% progressing to center GA and 23% progressing to CNV over a 5 year period. Indeed, when AREDS investigators scrutinized which fundus lesions preceded the development of GA at a particular location, they commonly observed that large drusen and DPEDs were previously present in these locations. They did not, however, define the sequence of events and steps through which these drusenoid lesions (an inclusive term for both drusen and even larger DPEDs) evolved into GA.

Though effective treatments for the neovascular complications of AMD have recently become available, the therapeutic options for preventing the development and progression of atrophy have been more limited. If new targets and treatments are to be developed, a better understanding of the sequence of progression from drusenoid lesions to GA may be of value.

Assessment of drusen and pigment alterations in previous studies have largely relied on evaluation of color fundus photographs. Indeed, commonly used and well-accepted AMD classification systems, such as the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System7 and the International Classification system8 are color photo based. These systems commonly use standardized reference circles of known size to provide semi-quantitative, categorical assessments of the severity and extent of AMD features of interest including both drusen and RPE alterations.

More recently, spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been advocated as a potentially useful tool for studying eyes with non-neovascular AMD. The high resolution and high sensitivity of spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) devices has provided excellent visualization of the morphology of drusen, and the overlying RPE and neurosensory retina9. In addition, the dense volume scanning capability of SD-OCT, has facilitated the automated segmentation and quantification of drusen, and the calculation of drusen volumes as well as areas of RPE atrophy10. Recently, drusen and GA quantification algorithms were Unites States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared and made available in commercial SD-OCT instruments. Some SD-OCT devices also feature the ability to track retinal position over time, allowing point-to-point correlation and precise longitudinal follow-up of specific lesions over time. Despite these capabilities, longitudinal studies of drusen and atrophy using SD-OCT have been relatively limited.

In this longitudinal study, we utilize a tracking-capable SD-OCT to follow individual drusenoid lesions (DL) over time, to gain a better understanding of the evolution of these lesions and the pathogenesis of atrophic AMD.

Methods

Data Collection

Consecutive patients with a diagnosis of non-neovascular AMD (NNVAMD) in at least one eye, who had undergone serial imaging over time using a Spectralis OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Vista, CA) at the Doheny Eye Institute between January 9, 2008 and October 18, 2011 were retrospectively collected. Eyes with other retinal diseases, including diabetic retinopathy, retinal artery occlusion/retinal vein occlusion, hereditary retinal disease, pathologic myopia, macular hole, as well as history of retinal surgery were excluded; however eyes with non-visually significant (as determined by the clinician) vitreomacular interface disease identified only by OCT (e.g. epiretinal membrane) were not excluded. Only eyes with Spectralis OCT imaging at all visits with image registration enabled and a minimum follow-up of 6 months (m) were included. The first available visit during the defined study period was considered the “baseline” visit, and all visits with registered Spectralis OCT scans during the study period were included in the analyses. Information regarding age, gender, race, history of ophthalmic diseases or surgeries, ophthalmic diagnosis, lens status, visual acuity were also collected. Approval for data collection and analysis was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of Southern California. The research adhered to the tenets set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

All Spectralis OCT volume scans were obtained in a 6 × 6 mm grid approximately centered on the fovea. The number of B-scans in the volume acquisition varied from 47-51, but because the registration function was required for eligibility, the same number of scans were acquired at each visit for each each subject. Raw OCT data were exported from the OCT instrument and analyzed the manufactured provided Spectralis viewing software (Spectralis product family, version 5.3).

Grading Methodology

One grader (YOY), certified for assessing OCT images at the Doheny Image Reading Center (DIRC), first reviewed each set of volume B-scan images for every eye in a longitudinal manner with the aid of the registration function. All DLs (defined as areas of RPE elevation from Bruch membrane) in each eye which were over 30 microns in maximal apical height (measured from Bruch membrane to the inner surface of the RPE) were selected for longitudinal evaluation. There were a few reasons for selecting the 30 micron cut-off. First, at this height, the internal reflectivity of the lesion could be clearly assessed to confirm that it had characteristics consistent with a drusenoid lesion. Second, previous study had shown that only those drusen deposits larger than 25–30 μm in diameter measured histopathologically were detectable clinically on color fundus images. Thus, lesions of this height tended to correspond to funduscopically visiable drusen11. To be selected, the DL needed only be present on at least one visit during the study period. In other words, in some cases, the DL was not present at a particular location at baseline, but was noted at a follow-up visit, and thus still included in the study. In addition to the first visit (defined as the baseline), subsequent visits were defined as follows: 1st follow-up (FU1, defined as visit that was 5m to 10m after the baseline, the visit that was closest to 6m was selected if more than one visit was available during this period), 2nd follow-up (FU2, defined as visit that was 11m to 16m after baseline, the one that most closest to 12m was selected if more than one visits found in this period), and last follow-up (FUL), defined as the final available visit. All DLs selected were given a unique label, and the B-scan within which the maximum height of the DL was noted was selected for the longitudinal assessments (corresponding, registered B-scans from the same location were used for all visits). The label was deemed to be specific to the location of the DL on the B-scan rather than the DL itself. This was a crucial distinction as the DL may not have been present at that location at an earlier visit, or could potentially disappear over time. For each DL (or DL location), the labeled OCT B-scan images were anonymized for subsequent detailed grading. Since more than one DL meeting the size criteria could be present on a single selected B-scan, separate labeled B-scan images were used for each DL. This strategy allowed each DL and B-scan to be assessed in an independent, masked fashion without knowledge of visit order, eye, or appearance of the lesion at a prior visit. This also facilitated subsequent replicated grading.

After the initial DL and visit selection, one grader (YOY) assessed each DL-visit independently, using detailed reading center OCT grading, featuring both qualitative morphologic descriptors as well as quantitative measurements. For each volume OCT scans, all available B-scans were reviewed systematically for assessment of all the features. The Spectralis software caliper tools were used to measure maximum DL height (MaxH, defined as the distance of inner RPE boundary to the inner boundary of Bruch membrane) and choroidal thickness (CT) directly below the DL on the same OCT B scan (if CT varied below the area of the DL, center of the lesion was chosen as the position to make the measurement), as well as subfoveal CT (SFCT). Numbers of B-scans (noBscan) subtended by the individual DL (an indirect measure of DL diameter) were also counted. In addition, morphologic features including the presence of hyper reflective foci (HRF) above the DL (corresponding clinically to pigment migration into the retina9), presence of atrophy (defined as loss of the RPE band with increased choroidal reflectivity on OCT) were graded to be present absent, or cannot grade.If a DLs was noted to have surrounding subretinal fluid, a grade of “not applicable” (NA) was given for HRF. If the presence of HRF was graded as present, the innermost retinal layer to which the HRF (LHRF) extended (over the DL) was also documented, with retinal layers defined to be: photoreceptor cell layers (PR), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), inner nuclear layer (INL), inner plexiform layer (IPL) and ganglion cell layer (GCL). Internal reflectivity of the DL (IRDL) was graded to be heterogeneous vs. homogenous (hetero. vs. homo.) Homogenous internal reflectivity was defined as the typical ground-glass medium reflectivity most typical of drusen on OCT. Heterogenous internal reflectivity was identified when foci of hyporeflectivity were noted within the DL.

A set of 200 DL-visits were randomly selected for independent replicate second grading. Another grader (AH) certified for assessing OCT images at the DIRC, evaluated these images independently with the same methodology used by first grader. Results from the two graders were compared, and for all discrepancies, the two graders met in open adjudication to determine a consensus result for each case. If the two graders could not resolve their disagreement, a final decision was made by the reading center director (SRS).

Statistical Analysis

Only gradable measurements and features were used for subsequent analyses in the study. Baseline and follow-up measurements, including CT directly below the DL (CTDL), MaxH and noBscan were compared with a paired t-test.

For the interest of evaluating possible predictors for new atrophy onset in our study, new atrophy onset at three time periods (from baseline to FU1, from baseline to FUL or from FU1 to FUL) were considered as positive outcomes. At each time point, proper possible predictors (features or measurement) were chosen, then the difference of these predictors were compared between new atrophy onset group and non-new atrophy group (Pearson Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact test were used for features and Independent-Samples T test or Man-Whitney test for measurement).

The generalized estimating equations (GEE) method was used to determine the association between each possible predictor and the outcome. The GEE method accounted for within-participant correlation of responses 12–15(i.e. DLs from the same patient were more likely to have similar outcome relative to the ones from other patients). The type of covariance matrix used to account for the within-patient correlations is the exchangeable correlation structure, and empirical standard error estimates were used to calculate 95% confidence interval (CI) for odds ratios.

SPSS (version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States) was used for the statistical analysis. A bilateral value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Three hundred and eleven eyes from 198 subjects with a diagnosis of NNVAMD were examined with the Spectralis OCT during the study period. Fifty three eyes had other retinal diseases or history of retinal surgeries. Two hundred and twelve eyes did not have follow up OCT images with registration for a period of at least 6 months. Twenty three eyes had no DL over 30 microns. Thus, 41 eyes from 29 patients were included in the study. A total of 571 DLs (543 individual lesions were identified at baseline, while 28 lesions developed during follow-up) were evaluated in the study.

Baseline Characteristics of Eyes with DLs

The average age of the participants at baseline was 77.2 ±8.4 years (range, 62-100 years). 72.4% (21/29) participants were female. 53.7% (22/41) of the eligible eyes were right eyes. The average logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (LogMar) visual acuity (VA) was 0.2±0.2 (Snellen acuity range, 20/20-20/200). 28 eyes with visible choroidal outer boundary subfoveally were observed, of which, the mean was 155.0 ±74.5 microns (range, 46-336 microns). On SD-OCT volume scans, the distance between B-scans was 121.3±2.8 microns (range, 117-127 microns). All DLs were adequate for grading of MaxH, presence/layer of HRF, IRDL and presence of local atrophy. A total of 399 lesions were documented with gradable CTDL measurements. A small minority of DLs (0.5% or 3/571) already had evidence of atrophy at the location of the DL at baseline. Among 47 DLs present with HRF (Table 1), 4 had LHRF in PR, 29 in ONL, 4 in OPL, 6 in INL, 3 in IPL and 1 in GCL. A detailed summary of the baseline characteristics of these DLs is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Baseline Drusenoid Lesions (DL) Characteristics for New Atrophy Onset at FU1 (or FUL) Group and Non-new Atrophy Onset at FU1 (or FUL) Group.

| Baseline Features | At Baseline | At FU1 | At Baseline | At FUL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| New Atrophy Onset Group | Non-new Atrophy Onset Group | New Atrophy Onset Group | Non-new Atrophy Onset Group | |||||

| No. DL | No. DL | No. DL | P valuea | No. DL | No. DL | No. DL | P valuea | |

| Atrophy | ||||||||

| Absent | 449 | 7 | 442 | NA | 567 | 18 | 549 | NA |

| Present | 2 | -- | 2 | 3 | -- | 3 | ||

| HRF | ||||||||

| Present | 42 | 5 | 37 | <0.001 | 47 | 8 | 39 | <0.001 |

| Absent | 409 | 2 | 407 | 523 | 10 | 513 | ||

| IRDL | ||||||||

| heterogeneous | 69 | 3 | 66 | 0.076 | 70 | 9 | 61 | <0.001 |

| homogeneous | 382 | 4 | 378 | 500 | 9 | 491 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Baseline Measurement | Mean ±SD (range, μm)/No. | Mean ±SD (range, μm)/No. | Mean ±SD (range, μm)/No. | P valueb | Mean ±SD (range, μm)/No. | Mean ±SD (range, μm)/No. | Mean ±SD (range, μm)/No. | P valueb |

|

| ||||||||

| MaxH | 71.67±34.95 (0∼267)/451 | 96.14±37.84 (63∼178)/7 | 71.28±34.81 (0∼267)/444 | 0.134 | 68.68±33.20 (0∼267)/570 | 96.78±29.35 (58∼178)/18 | 67.76±32.94 (0∼267)/552 | 0.001 |

| CTDL | 143.35±67.18 (30∼328)/327 | 139.71±72.51 (95∼301)/7 | 143.43±67.17 (30∼381)/320 | 0.897 | 157.33 ± 73.57 (30∼381)/399 | 109.76±56.74 (38∼301)/17 | 159.45±73.57 (30∼381)/382 | 0.006 |

P value represents the difference in association between the new atrophy onset group and the non-new atrophy onset group, P <0.05 was considered statistically significant; aP determined by Pearse Chi-Square test or Fisher's Exact Test, bP by Independent-Samples T test or Man-Whitney test; DL = drusenoid lesion; HRF=intraretinal hyperreflective features; IRDL= internal DL reflectivity; MaxH = Maximum DL Height; CTDL = choroidal thickness below DL; NA = not applicable; FU1 =1st follow up at 5-10 months after Baseline; FUL= last follow up in the study; No. = number; SD = standard deviation.

Characteristics of DLs at FU1

At FU1 (6m to 10m after baseline), 451 DLs had SD-OCT record adequate for the study. All DLs were adequate for grading of MaxH, IRDL and presence of local atrophy. CTDL were only gradable in 357 DLs. One eye developed neovascularization at 6m after baseline. In this eye, 6 DLs were noted to have overlying subretinal fluid, and thus were assigned a grade of “NA” for features of HRF, resulting in a total of 445 gradable DLs for HRF. In addition, 33 eyes with measurable SFCT were documented, of which, the mean was 166.4 ± 84.6 (range, 38 -336).

Characteristics of DLs at FU2

A total of 106 DL lesions had a visit at FU2 available in the study. The mean duration of FU2 to baseline was 13.2 ± 1.2 (range, 12-15) months. A total of 106 lesions with measurable MaxH and 103 lesions with measurable CTDLs were documented at FU2. MaxH of DLs ranged from 0 to 277 (mean ± SD, 68.0 ± 43.0) microns. CTDL was 168.0 ± 80.6 (range, 53-342) microns. Heterogeneous IRDL and HRF were seen in 8 out of 106 gradable lesions, respectively.

Characteristics of DLs at FUL

At FUL, 571 DL had SD-OCT record adequate for the study, among which, 570 DLs with gradable local atrophy, 560 DLs with gradable HRF (presence and layer) and 571 with gradable IRDL were observed. MaxH of all DLs was documented. A total of 544 lesions had visible choroidal outer boundary under DL. In addition, 23 eyes with measurable SFCT were documented, of which, the mean was 171.5 ± 83.8 (range, 65 - 351).

DL Features and Measurment Changes

SFCT

SFCT at baseline was not statistically thinner than that of FU1 (p=0.530, n=27) or that of FUL (p=0.619, n=19).

Size of DL

Changes in maximum height (MaxH) of DLs over time were calculated, and categorized using an arbitrary cut-point of 20 microns that was chosen a priori. From baseline to FU1, 451 DLs with measurable MaxH at both visits were analyzed: 13.1% (59/451) of DLs decreased by more than 20 microns in maximum height, 8.0% (36/451) increased by more than 20 microns and in 78.9% (356/451), the DL was relatively stable (change between -20 to 20 microns), yielding a mean change of 3.1 microns (range, -197 to 74 microns; SD, 24.1 microns). Among these lesions, 18 DLs that were not at baseline appeared at FU1, the mean MaxH of which was 50.1± 12.4 (range, 26-74) microns at FU1. On the opposite, 15 DLs that were at baseline disappeared at FU1. Their baseline MaxH range from 21 to 197 (mean ±SD, 79.2 ± 41.1) microns. If divided by the duration (m) from baseline, the rate of DL MaxH change varied from -20.6 microns/m to 8.8 (mean ±SD, 0.3 ±3.0) microns/m. Expressed as a percentage, DL could decrease by 100% (i.e. disappear) or increase to 1.8 times their baseline (mean ±SD, 0 ±30%) height (Figure 1). From baseline to FUL, 27 DLs that were absent at baseline were seen at FUL, of which, the average MaxH at FUL was 64.3 ± 16.0 (range, 37-102) microns. While 46 DLs that were observed at baseline were no longer visible at FUL, of which, the average MaxH at baseline was 78.4 ± 31.0 (range, 30-197) microns. Similarly, 26 DLs that were absent at FU1 were seen at FUL, of which, the average MaxH at FU1 was 70.3 ± 31.7 (range, 26-140) microns. While 8 DLs that were observed at FU1 were no longer visible at FUL, of which, the average MaxH at FU1 was 51.1± 8.0 (37-59) microns. Overall, there was a trend for average MaxH at FU1 (74.73±35.77 microns) to be higher than at baseline (71.67±34.95 microns) (p=0.07, n=451, Paired Sample T-Test) and average MaxH at FUL (77.92±40.85 microns) higher than at FU1 (74.73±35.77 microns) (p=0.026, n=451, Paired Sample T-Test). The change in number of B-scans subtended by the DL (noBscan; used an approximation for DL diameter), ranged from a decrease of 6 and an increase of 6 B scans (mean ±SD, -0.3±1.6) from Baseline to FUL.

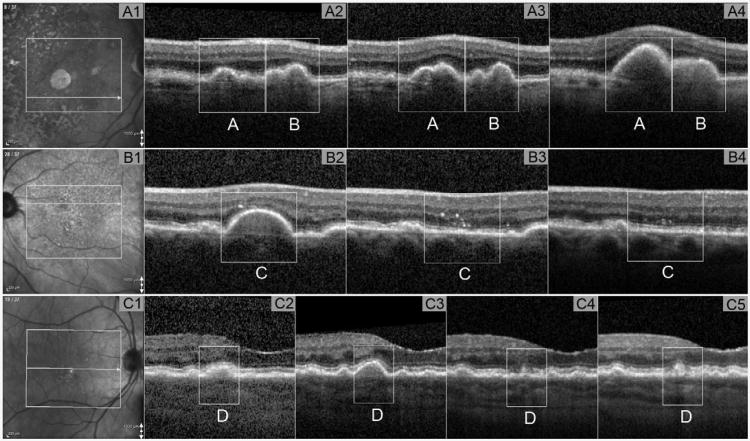

Figure 1. Example of change of maximum height of drusenoid lesion seen by SD-OCT.

Part A: example of MaxH increase. Part A1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part A2-A4: OCT B-scans where MaxH of DL(A) and DL(B) located. Part A2: MaxH for DL (A) = 96 microns, MaxH for DL (B) =93 microns at baseline. Part A3: MaxH for DL (A) =119 microns, MaxH for DL (B) =81 microns at 6m after baseline. Part A4: MaxH for DL (A) =303 microns, MaxH for DL (B) =132 microns at 27m after baseline. Part B: example of MaxH decrease. Part B1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part B2-B4: OCT B-scans where MaxH of DL(C) located. Part B2: MaxH for DL (C) =197 microns at baseline. Part B3: MaxH for DL (C) decreased to 0 microns at 10m after baseline. Part B4: MaxH for DL (C) remained at 0 microns at 15m after baseline. Part C: example of MaxH fluctuated. Part C1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part C2-C4: OCT B-scans where MaxH of DL (D) located. Part C2: MaxH for DL (C) =76 microns at baseline. Part C3: MaxH for DL (C) =115 microns at 10m after baseline. Part C4: MaxH for DL (C) =68 microns at 18m after baseline. Part B5: MaxH for DL (C) =87 microns at 44m after baseline. DL = drusenoid lesion; MaxH = maximum height of DL; OCT = optical coherence tomography; SD-OCT = spectral domain OCT; m = month.

CT

Out of all 571 DL evaluated in the study, 399 of 571 with visible choroidal outer boundary below DLs at baseline, 357 of 451 at FU1, 103 of 106 at FU2 and 544 of 571 at FUL were observed. The average change in CTDL was -5.1±18.2 microns from baseline to FU1 (n=295) and 7.4 ± 24.1 microns from baseline to FUL (n=395). There is a significant decrease in CTDL at FU1 (134.48± 63.94 microns) compared to baseline (139.49± 65.22 microns) (p<0.001, n=295, Paired Sample T-Test). Similarly, CTDL at FUL (139.30 ± 64 microns) was statistically lower than CTDL at FU1 (142.42± 67.70 microns) (p=0.003, n=352, Paired Sample T-Test).

HRF

Among all 571 lesions evaluated in the study, 571 at baseline, 455 at FU1, 106 at FU2 and 560 at FUL were adequate for grading of HRF. Migrated HRF (HRF change from absent to present, or LHRF increased more anteriorly) or decreased HRF (LHRF reduced, or HRF disappeared) were observed from baseline to FU1, or from baseline to FUL or from FU1 to FUL. For example, new (not present at baseline) overlying HRFs appeared at FU1 in 2.5% (11/445) of DLs, with extension as far as four layers anteriorly (from no HRF at that location at baseline to HRF present in the INL) (Figure 2). Meanwhile, definite HRF noted at baseline were no longer evident at FU1 in 1.1% (5/445) of DLs (Figure 2), also with a maximum reduction of three layers (from HRF in OPL to no HRF).

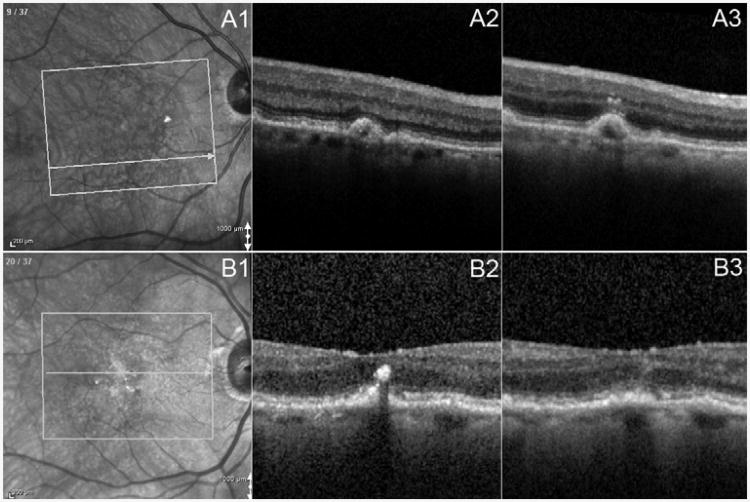

Figure 2. Example of change of features of hyper reflective foci seen by SD-OCT.

Part A: example of HRF increase. Part A1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part A2: OCT B-scan showing absent HRF related to DL at baseline. No HRF related to the same DL was found in any other B-scan. Part A3: OCT B-scan showing definite HRF present related to DL at 7m after baseline. LHRF was graded as inner nuclear layer. Part B: example of HRF decrease. Part B2: OCT B-scan showing definite HRF present related to DL at baseline. LHRF was graded as outer nuclear layer. Part B3: OCT B-scan showing absent HRF related to DL at 9m after baseline. No HRF was found in any B-scan related to the same DL. DL = drusenoid lesion; HRF = Hyper Reflective Foci; LHRF = layer of HRF; OCT = optical coherence tomography; SD-OCT = spectral domain OCT; m=month.

IRDL

A total of 571 lesions at baseline, 451 at FU1, 106 at FU2 and 571 at FUL were gradable records. IRDL changed from homogeneous to heterogeneous in 3.1% (14/451) DLs and conversely in 2.0% (9/451) DLs at FU1, compared to baseline. Overall, from baseline to FUL, there's a change of IRDL from homogeneous to heterogeneous in 4.7% (27/571) DLs and conversely in 1.4% (8/571). Examples were shown in Figure 3 (available at http://aaojournal.org).

DL characteristics as possible predictor for new atrophy onset: From baseline to FU1

A total of 451 DLs (451 gradable records for atrophy/HRF/IRDL/MaxH and 295 for CTDL) were available in this time period. The average duration from baseline to FU1 was 7.8 ± 1.4 (range, 5-10) months. New atrophy was noted in 1.6% (7/451) of DLs at FU1. The proportion of new atrophy onset at FU1 was found statistically higher among the DLs with baseline presence of HRF than those with absence of HRF (p<0.001, Table 1). However, when the DLs presented with HRF at baseline, the DLs with LHRF in the inner retina (including INL, IPL, GCL) did not have increased risk of new atrophy onset at FU1, compared to the ones with LHRF in the outer retina (including PR, ONL, OPL) (p=1.000, Fisher's Exact Test). Under similar condition, if HRF were present at baseline, no statistical significant difference of new atrophy onset was found between DLs with LHRF anterior than ONL (including OPL, INL, IPL, GCL) at baseline and the ones with LHRF at ONL (p=1.000, Fisher's Exact Test). For IRDL, the proportion of new atrophy onset at FU1 was not significantly different among DLs with baseline heterogenous internal reflectivity than those with homogeneous reflectivity (p=0.076, Table 1). Difference of baseline DL MaxH or CTDL between the new atrophy onset group and the non-new atrophy onset group was not statistically significant (p=0.134 and p=0.897, respectively, Table 1). However, taking into account of within eye and within patient correlations, presence of HRF or heterogenous IRDL or CTDL less or eaqual to 135 microns all statistically increased the risk of local atrophy onset at FU1 evaluated by GEE model. Their odds ratios determined by the GEE model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Odds Ratio of Baseline Drusenoid Lesion (DL) Parameters to Predict New Atrophy Onset at FU1 obtained by Generalized Estimated Equation.

| Predictors | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lower | higher | ||

| HRF (present vs. absent) at Baseline | 30.161* | 4.766 | 190.860 |

| IRDL (hetero. vs. homo.) at Baseline | 5.614* | 1.277 | 24.673 |

| Maximum DL Height (>80 microns vs. <=80 microns) at Baseline | 3.977 | 0.846 | 18.699 |

| CT below DL (<=135 microns vs. >135 microns) at Baseline | 7.987* | 1.555 | 41.022 |

represents statistically significant. DL = drusenoid lesion; HRF=intraretinal hyperreflective features; IRDL= internal DL reflectivity; hetero vs. homo= heterogeneous vs. homogeneous; CT = choroidal thickness; FU1 =1st follow up at 5-10 months after Baseline.

From baseline to FU2:

No new atrophy presented at FU2 compared to baseline, thus assessment of predicting model of baseline parameters for atrophy onset at this time point was not obtainable.

From baseline to FUL

The mean follow-up time from baseline to FUL was 21.3 ± 8.6 (range, 6-44) months. One DL had ungradable record for local atrophy at FUL, leading to a total of 570 DLs (570 gradable HRF/IRDL/atrophy/MaxH and 399 gradable CTDL) analyzed in this time period. New atrophy was noted in 3.2% (18/570) of DLs at FUL, compared to baseline. Presence of HRF at baseline, or heterogenous DL internal reflectivity at baseline, was significantly associated with new atrophy onset at FUL (all p<0.05, Table 1). When HRF was present at baseline, LHRF of DLs (outer retina vs. inner retina, or ONL vs. all other layers anterior to ONL) did not differ in the new atrophy onset group and the non-new atrophy onset group (both p>0.05). Difference of baseline DL MaxH or CTDL between the new atrophy onset group and the non-new atrophy onset group was statistically significant (p<0.05 respectively). After adjusted with eye and within patient correlations using GEE model, presence of HRF or heterogenous IRDL or MaxH over 80 microns or CTDL less or eaqual to 135 microns all statistically increased the risk of local atrophy onset at FUL. Their odds ratios were shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Odds Ratio of DL Parameters observed to Predict New Atrophy Onset at FUL obtained by Generalized Estimated Equation

| Predictors | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| lower | higher | ||

| HRF (present vs. absent) at Baseline | 11.211* | 2.513 | 50.019 |

| HRF (present vs. absent) at FU1 | 15.477* | 8.921 | 26.849 |

| HRF layer change+ (migrated vs. stable or decreased) | 28.214* | 12.737 | 62.495 |

|

|

|

||

| IRDL (hetero. vs. homo.) at Baseline | 7.005* | 2.300 | 21.337 |

| IRDL (hetero. vs. homo.) at FU1 | 6.133 | 0.535 | 70.273 |

| IRDL change++ (change from homo. to hetero. vs. homo. stable) | 6.548* | 3.163 | 13.557 |

|

| |||

| Maximum DL Height (>80 microns vs. <=80 microns) at Baseline | 7.886* | 2.105 | 29.538 |

| Maximum DL Height (>80 microns vs. <=80 microns) at FU1 | 5.132 | 0.263 | 99.996 |

|

| |||

| CT below DL (<=135 microns vs. >135 microns) at Baseline | 3.796* | 1.154 | 12.481 |

| CT below DL (<=135 microns vs. >135 microns) at FU1 | 1.194 | 0.145 | 9.823 |

represents statistically significant (p<0.05). HRF=intraretinal hyperreflective features; DL =drusenoid lesions IRDL= internal DL reflectivity; hetero vs. homo= heterogeneous vs. homogeneous; CT = choroidal thickness; FU1 =1st follow up at 5-10 months after Baseline; FUL= last follow up, change++ represents change observed from baseline to FU1; NA= not applicable.

From FU1 to FUL

The mean follow-up time from FU1 to FUL was 12.3 ± 8.6 (range 0-34) months. One upgradable record for local atrophy was at FUL. Thus, a total of 450 DLs were analyzed in this time period. Nine new atrophy was observed at FUL compared to FU1. Features and measurement at FU1, as well as change of these characteristics observed at FU1 are shown in Table 4 (available at http://aaojournal.org). Possible risk predictors were also evaluated by GEE models by considering within eye and within patient correlations (Table 3). Of note, similarly as above, presence of HRF at FU1, but not LHRF at FU1 increased the risk of DLs to develop atrophy at FUL. However, increased change of LHRF from baseline to FU1 (i.e. migrated HRF: HRF change from absent to present, or LHRF increased more anteriorly) was positively correlated with the new atrophy onset at FUL (OR=28.214, CI=12.737-62.495, Table 3). IRDL at FU1 was not significant associated with new atrophy onset at FUL; however, change of IRDL from baseline to FU1 was positively correlated with new atrophy onset: DLs with internal reflectivity change from homogenous to heterogeneous had 2 to 12 times higher risk to develop new local atrophy at FUL compared to the ones with homogenous reflectivity throughout the first 6m study period (Table 3). DLs with MaxH over 80 microns at FU1 or DLs with CTDL less than 135 microns at FU1 was not significantly associated with new atrophy onset at FUL (Table 3). In addition, no difference of change of MaxH or change of CTDL from baseline to FU1 between new atrophy onset group and non-new atrophy onset group, was found significant (both p>0.05, Table 4, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Intergrader Reproducibility

Substantial to almost perfect agreement16 indicated by Kappa values were achieved for inter-grader reliabilities for DLs features (HRF: 0.739 and IRDL: 0.855). The Bland Altman analysis indicated that the 95% limits of agreement between the two graders ranged from -22.59 to 22.85 (mean, 0.13) microns for CTDL and -13.29 to 18.25 (mean, 2.48) microns for MaxH (Figure 4 (available at http://aaojournal.org)). The variation is relatively small for this data set.

Example Cases of Incident Atrophy at the Location of Drusenoid Lesions

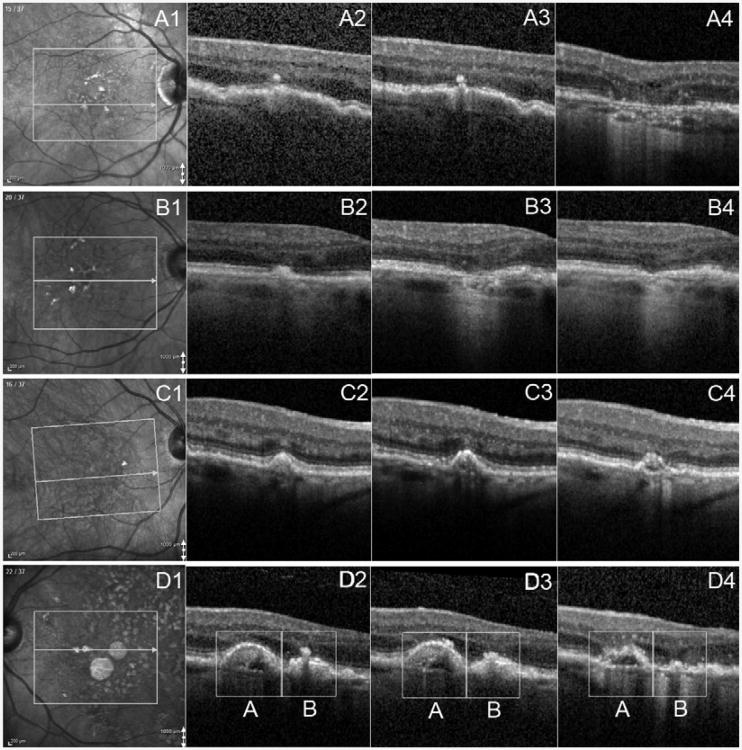

Case 1 illustrates the progression of a DL with overlying HRF to atrophy in the right eye of a 71 year-old women, whose Snellen VA at baseline was 20/30. Baseline OCT B-scans showed definite HRF without any evidence of atrophy (Figure 5A2). Twenty eight months later, definite atrophy was present at this same location (Figure 5A4).

Figure 5. Case Examples of New Atrophy Onset seen by SD-OCT.

Part A: example of new atrophy onset related to HRF. Part A1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part A2: OCT B-scan showing definite HRF related to DL without evidence of atrophy at baseline. Part A3: OCT B-scan showing definite HRF without atrophy at 2m after baseline. Part A4: OCT B-scan showing definite atrophy with HRF at 28 months after baseline. Part B: example of new atrophy onset related to homogeneous DL. Part B1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part B2: OCT B-scan showing absent atrophy at baseline IRDL as homogeneous. Part B3: OCT B-scan showing clearance of DL but presence of atrophy at the same location at 9m after baseline. HRF was also noted in the outer nuclear layer. Part B4: OCT B-scan showing atrophy at 21m after baseline without evidence of HRF. Part C: example of new atrophy onset related change of IRDL. Part C1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part C2: OCT B-scan showing IRDL graded as homogeneous. Part C3: OCT B-scan showing IRDL changed to heterogeneous without presence of atrophy at 9m after baseline. Part C4: OCT B-scan showing presence of new atrophy at 21m after baseline. Part D: example of new atrophy onset related HRF and IRDL. Part D1: Infrared image showing B-scan location on the fundus at baseline. Part D2: OCT B-scan showing DL (A) and DL (B) both with IRDL as heterogeneous. DL (B) had definite HRF while DL (A) had not. Part D3: OCT B-scan showing DL (A) with new HRF present at 11m after baseline. Part D4: OCT B-scan showing presence of new atrophy for both DL (A) and DL (B) at 27m after baseline. DL = drusenoid lesion; IRDL = Internal Reflectivity of DL; HRF = hyper reflective foci; OCT = optical coherence tomography; SD-OCT = spectral domain OCT; m=month.

Case 2 illustrates new atrophy which developed at the former location of a DL with homogenous internal reflectivity in the right eye of a 74 year-old man. His Snellen VA was 20/25 at baseline. Baseline OCT B-scan reveal the absence of atrophy at this location (Figure 5B2). Nine months later, however, the DL has regressed and atrophy is now noted at the same location with HRF noted in the ONL (Figure 5B3). Later, 21 months after baseline, definite atrophy is still noted, but now the overlying HRF has disappeared (Figure 5B4).

Case 3 illustrates the right eye of an 84 year-old woman with non-neovascular AMD. Snellen VA was 20/20 at baseline, and the DL illustrated in this example was graded to have a homogenous internal reflectivity (Figure 5C2). Subsequently, at month 9, the internal reflectivity (IRDL) had become heterogenous but no atrophy was observed (Figure 5C3). Twenty one months after baseline, new atrophy was noted (Figure 5C4).

Case 4 illustrates a case of new atrophy in the left eye of an 81 year-old female. At baseline, her Snellen VA was 20/25. Two DLs (A and B) with heterogeneous IRDL were shown on the same B-scan (Figure 5D2). DL (B) demonstrated HRF at baseline (Figure 5D2) while DL (A) developed overlying HRF 11 months after baseline (Figure 5D3). At 27 months after baseline, new atrophy was noted at both locations (Figure 5D4).

Discussion

In this study, detailed SD-OCT based measurements and feature descriptions enabled observation of the natural history of individual DL changes during the study period and aided in the identification of potential high risk features for development of local RPE atrophy. The presence of HRF overlying the drusen, or a heterogenous internal reflectivity (IRDL), or CTDL less than 135 microns at baseline was noted to increase the risk of development of local atrophy over the ensuing months. The migrated HRF and the change of IRDL from homogeneous to heterogeneous during the study period were also predictive of atrophy development by the final follow-up visit.

Previous reports have found that AMD eyes with DPEDs possess a high risk of progressing to atrophy over time.2–4,6,17 However, these studies were designed to assess global risk of the eye(s), and did not focus on local progression at the location of individual lesions. Because individual drusenoid lesions are known to appear and disappear over time in a dynamic fashion,6,10,15 understanding the precise spatial relationship between these lesions and development of atrophy would appear to be importance in order to gain a better understanding of AMD pathogenesis. In addition, previous focused on data derived from the study of color photographs. Thus, assessment of potentially important features of drusen, such as internal reflectivity and drusen height, were not possible. These characteristics, however, can be studied with high quality OCT imaging. In addition, by using a tracking capable OCT using simultaneous dual-beam system, and an automatic registration re-scan feature, the same fundus location can be sampled over time with a high degree of precision. This is a point worth emphasizing, and was the major factor limiting the number of cases available for inclusion in this study. All selected cases had the registration feature enabled and follow-up scans were obtained with the rescan feature. In other words scans were not obtained and then registered after the fact, but rather the follow-up scans were acquired at the same location as the prior scans. The repeatability of the Spectralis for thickness measurements using this strategy has been shown to be excellent (Gregori G, Rosenfeld JP. Using OCT Fundus Images to Evaluate the Performance of the Spectralis OCT Eye Tracking System. Poster presented at: ARVO Annual Meeting, May 2011; Fort Lauderdale). Most critically, for the current study, requiring this registration mode enhances our confidence in the longitudinal comparisons of the features and metrics of the drusenoid lesions.

As observed in our study, individual DLs demonstrated a dynamic and variable evolution during the study period. For example, the change in the maximum height of the drusenoid lesion (MaxH) varied from a decrease of 197 microns to an increase of 207 microns, with a change rate ranging from -20.6 microns/month to 8.8 microns/month. On average, DLs tended to increase in height over time during the course of our study. On the other hand, a DL as high as 197 microns, was noted to disappear completely. MaxH at baseline was significantly positively associated with new atrophy onset at FUL (Table 2 and 3); however, when a shorter period was chosen (6m), it no longer remained as an independent predictor of atrophy development (Table 2 and 3). NoBscan (i.e. a measure of drusen diameter) was not a predictor for atrophy progression at any time point. However, this assessment was confounded by the fact that there was some variability (albeit small) in the density of B-scans in the volume cubes among the cases. In addition, the average distance between B-scans in our study was 121.3±2.8 microns. Thus our NoBscans parameter will be a noisy surrogate for drusen diameter. It is possible, with a more dense volume scan, noBscan may be found to be an important predictor.

CTDL at baseline was associated with atrophy at FU1 and FUL (both p<0.05), however CTDL at FU1 was not an indicator for incident atrophy at FUL (Table 2 and 3). The CTDL measurement showed significant variation in our study and may reflect the underlying spatial variation in posterior pole choroidal thickness that has been previously described.18 With the future availability of large normative databases of choroidal thickness, it may be possible to adjust or normalize the CTDL for the macular location, and reassess its predictive value. Also, CTDL values in our study were not corrected for time of day. Recent studies have demonstrated that choroidal thickness shows a diurnal variation.19 The magnitude of this diurnal variation, however, is small in eyes with thinner choroids, and thus may not be an important factor in the older AMD cohort.

In the current study, risk factors for progression of a DL to atrophy demonstrated good internal consistency (Table 2 and 3). For example, baseline factors (heterogenous IDRL and presence of HRF) found to be positively associated with new atrophy onset both at 6m or FUL in the study. In addition, when considering changes in DL characteristics from baseline to FU1, migrated HRF (HRF change from absent or present, or LHRF increased) or change of IRDL from homogeneous to heterogeneous again significantly increased the risk for atrophy progression at FUL (p<0.05, Table 3). According to our GEE models, the DLs with overlying HRF at baseline were more likely to progress to atrophy at 6m or later than the ones without HRF (Table 2 and 3). However, once HRF was present at baseline, the DLs with the innermost extension of HRF at more anterior retinal layer at baseline did not show increased risk of new atrophy onset later on(p>0.05).

Although the exact mechanism underlying the development of atrophy at this location is unclear, HRF and/or IDRL appear to be relevant to understanding the progression of AMD. Increased heterogeneity of the internal structure of a drusenoid lesion (with increasing hyporeflective spaces), may represent a softening of drusen and a greater likelihood of collapse of the drusen. HRF are thought to represent migration of pigment (RPE cells) into the neurosensory retina.9 If the RPE cells have left their normal position in the monolayer, perhaps it is not surprising that atrophy at the RPE monolayer is noted subsequently. On the other hand, atrophy was noted to develop in the absence of prior HRFs, as shown in Figure 5B. It should be noted, however, that the inter B-scan distance was 121.3±2.8 microns, and thus small HRF could potentially be repeatedly missed by longitudinal B-scans which were taken at the same location each time using the rescan registration feature.

Our study has several important limitations including its retrospective nature and the relative paucity of subjects with long follow-up periods. The small number of subjects was in large part due to the stringent requirement that all follow-up scans had to be acquired using the rescan registration feature. On the other hand, despite the smaller number of subjects, a reasonably large number of individual drusenoid lesions were studied. Tagging and labelling a large number of drusenoid lesions is an arduous task. Another important limitation is the variable follow-up period for the final follow-up visit, a consequence of the retrospective design. To partially address this, we did choose one standardized follow-up interval (6 months) to better study associations across the large proportion of the cohort. Although this 6 month time point would seem to be quite short, there may be potential value in identifying risk factors that predict atrophy at such a short time interval – particularly for use in identifying high-risk subjects to include in new therapeutic trials. The B-scan density of the OCT volume scans is another limitation. As noted above, small but potentially important features such as intraretinal hyper-reflective features (pigment migration) or small drusen, could have potentially been missed. Even with dense OCT scans, certain drusen subtype, e.g. subretinal drusenoid deposits could be missed due to the inability of the current SD-OCT technique. In addition, although the rescan feature of the Spectralis is thought to have excellent precision, small amounts of mis-registration can certainly not be excluded (Gregori G, Rosenfeld JP. Using OCT Fundus Images to Evaluate the Performance of the Spectralis OCT Eye Tracking System. Poster presented at: ARVO Annual Meeting, May 2011; Fort Lauderdale). Because we were scrutinizing small fundus features, it is possible that even these small degrees of misalignment could have significance. Obtaining a higher density volume scan with a tracking OCT in AMD patients, however, may be difficult without reducing the amount of averaging/oversampling for individual B-scans which could compromise the image quality. A final limitation (or strength depending on one's perspective) of our study is that the assessments of drusen features and atrophy were based exclusively on OCT images. Although an excellent correlation has been demonstrated between atrophy measured by OCT and fundus autofluorescence, OCT-determined atrophy may not be equivalent to clinically determined atrophy.

Despite these many limitations, for a pilot analysis, our study has many strengths including the use of certified reading center AMD OCT graders, a standardized grading protocol, confirmation of grading reproducibility, a large number of individual drusenoid lesions, the use of tracked and registered OCT data. We believe the findings from our analysis may be useful for generating hypotheses to be confirmed in larger, prospective studies. The future implementation of automated algorithms to automatically label and track individual drusen and overlying features should facilitate these limitations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Antonia M. Joussen from Department of Ophthalmology, Charité University Medicine, Berlin, Germany, for her helpful discussion and statistical suggestion of the final manuscript.

This research has been supported in part by, NEI Grant R01 EY014375, Research to Prevent Blindness, and the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology at Moorfields Eye Hospital and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG grant He 6094/1-1).

Dr. Keane has received a proportion of his funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology at Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Abbreviations

- DL

drusenoid lesion

- SD-OCT

spectral domain optical coherence tomography

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- NNVAMD

non-neovascular AMD

- DPED

drusenoid pigment epithelium detachment

- MaxH

maximum height

- CTDL

choroidal thickness directly below the DL

- SFCT

subfoveal choroidal thickness

- HRF

intraretinal hyperreflective features

- PR

photoreceptor cell layers

- ONL

outer nuclear layer

- OPL

outer plexiform layer

- INL

inner nuclear layer

- IPL

inner plexiform layer

- GCL

ganglion cell layer

- IRDL

internal reflectivity of the DL

- LHRF

innermost layer extent of HRF

Footnotes

Disclosure: Drs. Sadda is an inventor of Doheny intellectual property related to optical coherence tomography that has been licensed by Topcon Medical Systems, and has served as a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Optos.. Dr Sadda also receives research support from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Optos, and Optovue, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gregori G, Wang F, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging of drusen in nonexudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird AC, Marshall J. Retinal pigment epithelial detachments in the elderly. Transactions of the ophthalmological societies of the United Kingdom. 1986;105(6):674–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roquet W, Roudot-Thoraval F, Coscas G, Soubrane G. Clinical features of drusenoid pigment epithelial detachment in age related macular degeneration. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004;88:638–642. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.017632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casswell AG, Kohen D, Bird AC. Retinal pigment epithelial detachments in the elderly: classification and outcome. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1985;69:397–403. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.6.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zweifel SA, Imamura Y, Spaide TC, et al. Prevalence and significance of subretinal drusenoid deposits (reticular pseudodrusen) in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1775–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cukras C, Agrón E, Klein ML, et al. Natural history of drusenoid pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration: Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report No. 28. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:489–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, et al. The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1128–34. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bird AC, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. Survey of ophthalmology. 1995;39:367–74. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keane PA, Patel PJ, Liakopoulos S, et al. Evaluation of age-related macular degeneration with optical coherence tomography. Survey of ophthalmology. 2012;57:389–414. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yehoshua Z, Wang F, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. Natural history of drusen morphology in age-related macular degeneration using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarks SH, Arnold JJ, Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP. Early drusen formation in the normal and aging eye and their relation to age related maculopathy: a clinicopathological study. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1999;83:358–68. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.3.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MDdeB, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. American journal of epidemiology. 2003;157:364–75. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JR. The chi 2 test for data collected on eyes. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1993;77:115–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van de Ven JPH, Boon CJF, Smailhodzic D, et al. Short-term changes of Basal laminar drusen on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012;154:560–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartnett ME, Weiter JJ, Garsd A, Jalkh AE. Classification of retinal pigment epithelial detachments associated with drusen. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 1992;230:11–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00166756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouyang Y, Heussen FM, Mokwa N, et al. Spatial distribution of posterior pole choroidal thickness by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52:7019–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan CS, Ouyang Y, Ruiz H, Sadda SR. Diurnal variation of choroidal thickness in normal, healthy subjects measured by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012;53:261–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.