Abstract

Riboswitches in messenger RNAs carry receptor domains called aptamers that can bind to metabolites and control expression of associated genes. The Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis has two representatives of a class of riboswitches that bind flavin mononucleotide (FMN). These riboswitches control genes responsible for the biosynthesis and transport of riboflavin, a precursor of FMN. We found that roseoflavin, a chemical analog of FMN and riboflavin that has antimicrobial activity, can directly bind to FMN riboswitch aptamers and downregulate the expression of an FMN riboswitch-lacZ reporter gene in B. subtilis. A role for the riboswitch in the antimicrobial mechanism of roseoflavin is supported by our observation that some previously identified roseoflavin-resistant bacteria have mutations within an FMN aptamer. Riboswitch mutations in these resistant bacteria disrupt ligand binding and derepress reporter gene expression in the presence of either riboflavin or roseoflavin. If FMN riboswitches are a major target for roseoflavin antimicrobial action, then future efforts to develop compounds that trigger FMN riboswitch function could lead to the identification of new antimicrobial drugs.

Keywords: antibiotic, antimetabolite, aptamer, Bacillus subtilis, flavin mononucleotide, riboflavin, Streptomyces davawensis

Introduction

Riboswitches are gene control elements usually found in the 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of bacterial mRNAs where they modulate gene expression upon binding to metabolites.1–4 Riboswitches that bind to flavin mononucleotide (FMN), the phosphorylated derivative of riboflavin,5,6 regulate genes involved in riboflavin production and transport.7 In B. subtilis, one FMN riboswitch is located in the 5′ UTR of the ribDEAHT (ribD) operon5,6 which is named after the homologous genes in Escherichia coli and encodes five enzymes required for riboflavin biosynthesis.8,9 When this riboswitch binds to FMN, a transcription terminator stem is predicted to form and halt synthesis of the ribD mRNA before any nucleotides of the first open reading frame (ORF) are synthesized.5,6,10 A second FMN riboswitch is located in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the ypaA gene (also called ribU)11 which encodes a putative riboflavin transporter.5,11,12 Most likely, FMN binding by the riboswitch prevents the initiation of ypaA translation via a mechanism involving sequestration of the ribosome binding site.5

Roseoflavin, a natural pigment originally isolated from Streptomyces davawensis, is an antimetabolite analog of riboflavin and FMN that has antimicrobial properties.13,14 Roseoflavin-resistant strains of B. subtilis and Lactococcus lactis have been identified and many of these mutants overproduce riboflavin.15–20 This has prompted efforts to develop bacterial strains that could be used to enrich riboflavin content in foods.18,20 We21 and others22 noticed that many of the mutations found in these roseoflavin-resistant strains are located within the aptamer region of ribD FMN riboswitches. Because FMN riboswitches normally turn off transcription of riboflavin biosynthesis genes upon ligand binding,5,6,10 the overproduction of riboflavin could be caused by the inability of mutant riboswitches to bind FMN and repress gene expression.

There is accumulating evidence indicating that riboswitches may act as antimicrobial drug targets.21–28 For example, pyrithiamine pyrophosphate is an analog of thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) that directly binds to TPP riboswitches and exhibits antimicrobial activity.26–28 Similarly, antibiotic lysine analogs including S-(2-aminoethyl)-L-cysteine bind to lysine riboswitches.24,25 Thus, we set out to determine whether roseoflavin binds natural FMN aptamers, and if so, whether roseoflavin affects gene expression mediated by FMN riboswitches.

Results

Roseoflavin binds to FMN riboswitches

We used an in-line probing assay29,30 to determine whether roseoflavin is capable of binding to an FMN riboswitch aptamer from B. subtilis (Fig. 1). Internucleotide linkages in regions of structured RNA tend to spontaneously cleave with a lower rate constant than linkages present in unstructured regions.29 In-line probing assays can be used to confirm ligand binding and to map the locations of the resulting structural changes. Furthermore, in-line probing data generated at various concentrations of ligand can reveal dissociation constant (KD) values for RNA-ligand interactions and can reveal the stoichiometry of complex formation.31

Figure 1.

Ligand binding by an FMN riboswitch from B. subtilis. (A) RNA sequence and predicted secondary structure model of the 165 ribD 5′ UTR from B. subtilis5 The two G residues at the 5′ end were added to increase the yield of transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. (B) Chemical structures of FMN, riboflavin, and roseoflavin. (C) RNA products generated by incubating 5′ 32P-labeled 165 ribD RNA under in-line probing conditions with concentrations of roseoflavin ranging from 0 to 50 µM. Products were separated by denaturing PAGE. Several bands corresponding to RNase T1 cleavage (3′ of G residues) are annotated. Pre identifies the uncleaved precursor RNA. NR, T1 and −OH identify lanes containing RNA subjected to no reaction, partial digest with RNase T1, and partial alkaline digestion, respectively. (D) Plot of the normalized fraction of 165 ribD RNA modulated versus the concentration of roseoflavin. The sites of modulation that were quantitated are indicated in (C). Theoretical binding curves for FMN and riboflavin (dashed lines) are based on the KD values reported previously.5

A 165 nucleotide RNA sequence containing the ribD FMN riboswitch aptamer from B. subtilis5 was incubated with a range of roseoflavin concentrations under in-line probing conditions. The pattern of bands produced by spontaneous RNA cleavage changes at four locations when a sufficient concentration of roseoflavin is added to in-line probing reactions (Fig. 1C). A plot of the fraction of RNA undergoing modulation at these sites versus the concentration of roseoflavin present yields a binding curve that is typical of a one-to-one interaction between ligand and RNA.31,32 Thus, roseoflavin binds the aptamer with characteristics that are similar to those previously observed for FMN binding5,10 by the same RNA construct.

An apparent dissociation constant (KD) of ~100 nM was estimated from the in-line probing data generated in the presence of roseoflavin (Fig. 1C, 1D). Compared to the KD values previously established for the 165 ribD RNA,5,10 the aptamer has a stronger affinity for FMN (KD ~5 nM) than roseoflavin, whereas riboflavin (KD ~3 µM) binds less tightly than the antimetabolite (Fig. 1D). These findings suggest that the dimethylamino group on the pteridine ring of roseoflavin (Fig. 1B) permits more favorable binding to the aptamer than the methyl group it replaces.

Genes controlled by FMN riboswitches are required for optimal growth of B. subtilis

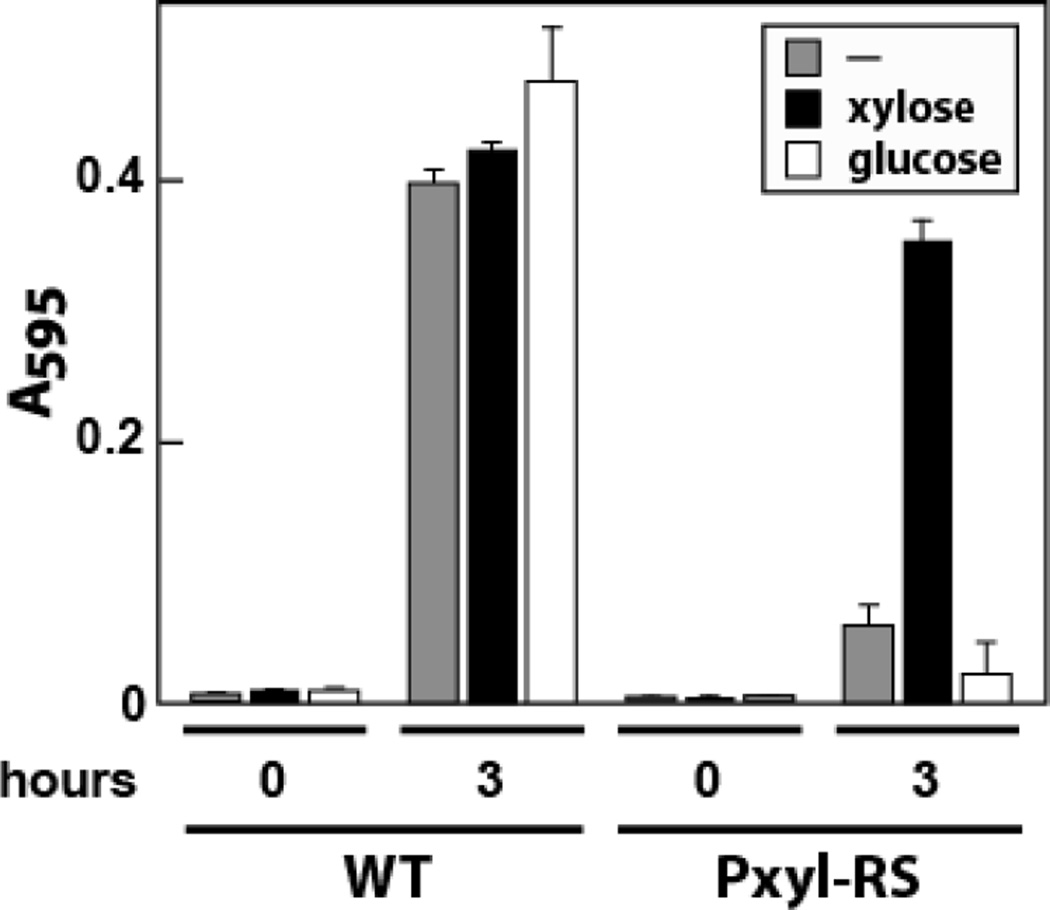

Because roseoflavin is an antimicrobial compound that can directly bind to FMN riboswitches in vitro, we speculated that its mode of action could involve inhibiting the expression of genes encoding FMN biosynthesis and transport proteins. To assess this possibility, we sought to determine whether expression of the ribD operon controlled by the 165 ribD aptamer examined above is essential for cell growth. The natural control regions (promoter and riboswitch) of the B. subtilis ribD operon were replaced in the chromosome with a xylose-inducible, glucose-repressible promoter (Pxyl),33 and the downstream ribD operon mRNA was modified by deleting the region of the 5′ UTR carrying the ribD riboswitch (-RS). The resulting strain was named Pxyl-RS.

Liquid cultures of B. subtilis carrying the Pxyl-RS alteration did not grow in rich (2XYT) medium without the addition of xylose (data not shown). Therefore, cultures were supplemented with xylose and grown overnight (approximately 15 hours), diluted in 2XYT medium to an OD600 of ~0.1 and grown for an additional hour. Cultures of WT cells were prepared identically except that xylose was excluded from the medium.

The cells from WT and Pxyl-RS bacterial cultures subsequently were pelleted, washed several times with 2XYT lacking xylose, diluted to an OD600 of ~0.01 in 2XYT medium, and grown in the presence or absence of 0.5% (w/v) xylose or glucose. Cell growth monitored by measuring the absorbance at 595 nm was robust for WT bacteria regardless of whether the medium was supplemented with xylose or glucose (Fig. 2). In contrast, growth was severely limited when Pxyl-RS bacteria were cultured in the absence of xylose, while the addition of xylose restored growth to approximately the same levels observed for WT cells. The addition of glucose further inhibited Pxyl-RS bacteria growth, which is consistent with the inhibitory action of this sugar on the expression of genes controlled by Pxyl promoters.33

Figure 2.

FMN riboswitches control genes essential for optimal bacterial growth in B. subtilis. For the Pxyl-RS variant, the natural ribD promoter was replaced with a xylose-inducible and glucose-repressible promoter, and the FMN riboswitch was deleted. WT and Pxyl-RS bacteria were grown in the presence or absence of 0.5% xylose or glucose and absorbance at 595 nm was measured.

Restricted expression of FMN biosynthesis genes disrupts normal growth of B. subtilis, which provides a possible rationale for the action of roseoflavin. A number of the ribD operon genes have homologs in E. coli, and these also have been shown to be essential for growth.34 Thus, roseoflavin or its phosphorylated derivative that more closely mimics FMN conceivably could bind to the ribD riboswitch and repress the synthesis of FMN even when bacterial cells are starved for this essential coenzyme.

Roseoflavin modulates the expression of genes controlled by FMN riboswitches and natural riboswitch mutations disrupt roseoflavin-mediated repression

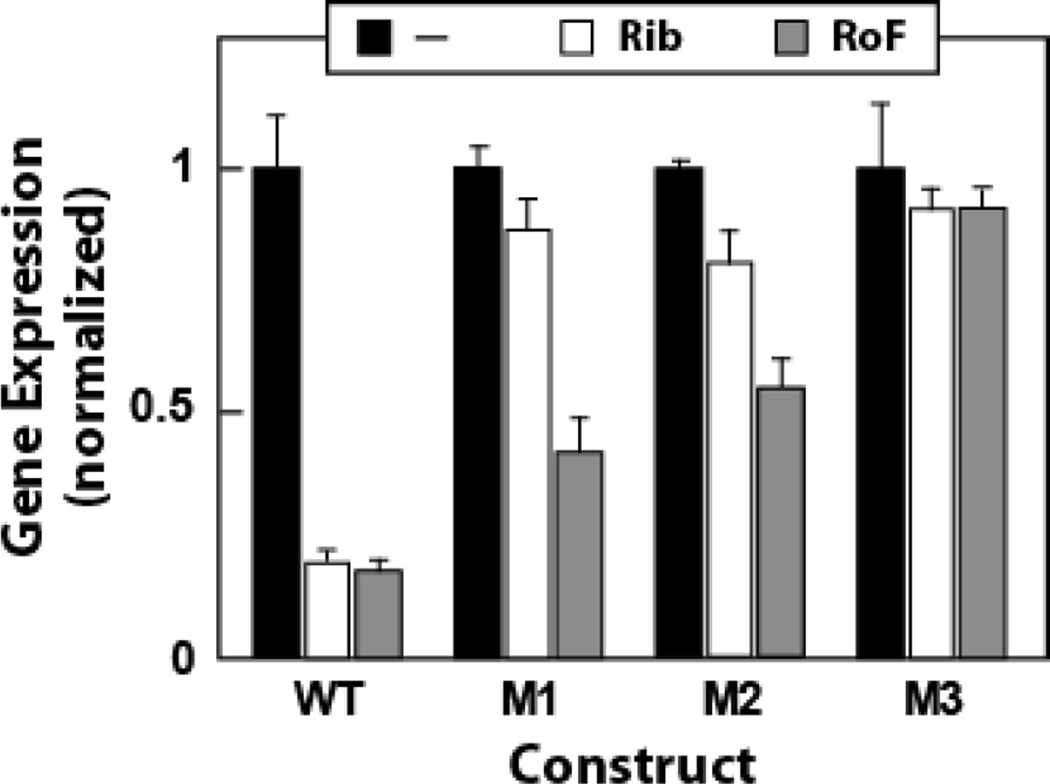

To further assess whether the antimicrobial activity of roseoflavin may be caused by riboswitch binding, we assessed the ability of roseoflavin to alter the expression levels of reporter genes controlled by wild-type (WT) or mutant FMN riboswitches. Of particular interest were three previously identified guanosine to adenosine point mutations that map to the B. subtilis 165 ribD FMN aptamer at nucleotide positions 41 (M1), 60 (M2), and 133 (M3) (Fig. 1A). These mutations were found in strains of B. subtilis that exhibit resistance to roseoflavin.15

Wild-type and mutant B. subtilis ribD FMN riboswitches were fused to an E. coli lacZ gene and cloned into the B. subtilis amyE locus. Unfortunately, the reporter activities of these constructs were very low (data not shown). To enhance reporter gene expression levels, we replaced the natural ribD operon promoter of the reporter constructs with the promoter for the B. subtilis lysC gene.36 We have used this strategy previously36 to improve the expression of riboswitch-reporter gene fusion constructs and to remove any possibility that the natural promoter carries additional regulatory elements.

Results from gene expression assays using B. subtilis cells carrying reporter constructs driven by lysC promoters are depicted in Fig. 3. When the medium was supplemented with riboflavin or roseoflavin (100 µM), expression of the reporter gene carrying the WT riboswitch decreased to less than one fifth the levels observed when bacteria were grown without supplementation. This is consistent with the prediction that when riboflavin or roseoflavin are imported via YpaA transport proteins5,11,12 and phosphorylated by RibC to FMN or roseoflavin phosphate, respectively,8,37 the compounds will bind to FMN riboswitches to repress the production of riboflavin biosynthesis proteins.5,6,10 In contrast, expression of reporter genes carrying either the M1 or M2 riboswitch mutants were almost unaffected by riboflavin supplementation, and only decreased to about half the maximum expression level in the presence of roseoflavin. The M3 riboswitch variant exhibited almost no suppression of reporter gene expression with either riboflavin or roseoflavin.

Figure 3.

Riboflavin and roseoflavin yield similar levels of expression from a reporter gene controlled by wild-type or mutant ribD FMN riboswitches from B. subtilis. Wild-type and three selected roseoflavin-resistant mutant15 ribD FMN riboswitches from B. subtilis were fused to an E. coli lacZ gene and inserted into the amyE locus of B. subtilis. Bacteria were grown in glucose minimal medium with 100 µM riboflavin or roseoflavin for approximately two hours before β-galactosidase assays were performed. Mutants have a single G to A substitution at position 41 (M1), 60 (M2), or 133 (M3), where the nucleotide numbers correspond to those in Figure 1A. Maximum Miller units measured were 68, 75, 105, and 50 for cells carrying WT and M1 through M3 RNAs, respectively.

The same trends in reporter gene expression levels were seen with these riboswitch constructs under the control of the natural ribD promoter, but the overall expression levels were significantly lower (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that roseoflavin supplementation indeed suppresses expression of genes controlled by an FMN riboswitch. Furthermore, mutations in an FMN riboswitch that emerged in roseoflavin-resistant bacteria exhibit reduced regulatory response when either riboflavin or roseoflavin are added to the medium.

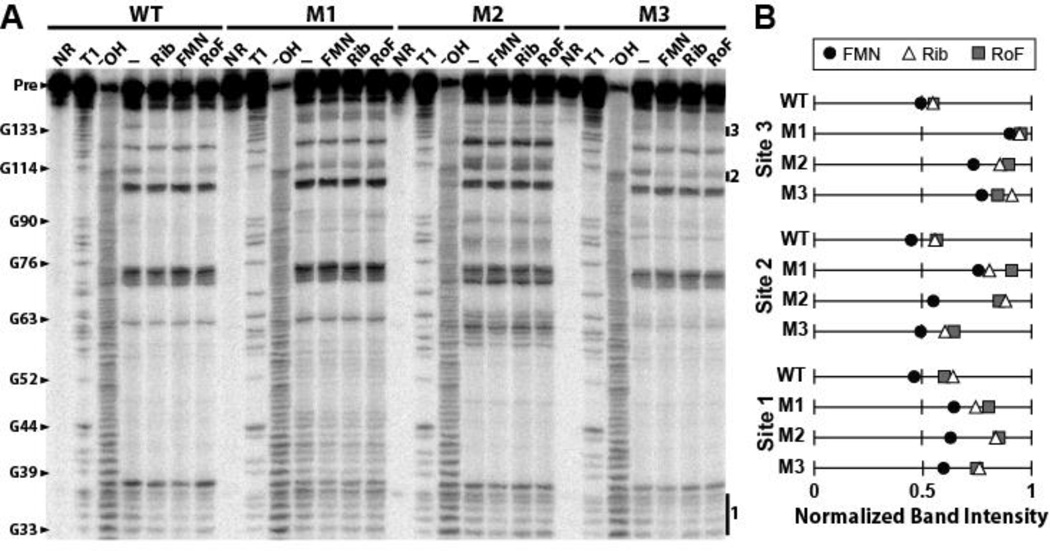

FMN riboswitch aptamer mutations from roseoflavin-resistant bacteria disrupt ligand binding

The responses exhibited by the reporter gene constructs carrying WT or mutant aptamers (Fig. 3) indicate that roseoflavin or (we speculate more likely) its phosphorylated derivative triggers the WT riboswitch to repress gene expression, whereas the mutant riboswitches may bind ligands less tightly. The ability of the mutant riboswitch aptamers to bind ligands was assessed by conducting in-line probing assays using mutant 165 ribD RNA constructs from B. subtilis. Each construct was incubated with 10 µM FMN, riboflavin or roseoflavin under in-line probing conditions, and the resulting patterns of spontaneous cleavage products were assessed (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Mutations to the FMN riboswitch that confer roseoflavin resistance disrupt ligand binding. (A) Wild-type and mutant 5′-labeled ribD RNAs were subjected to in-line probing in the presence of no compound (–) or 10 µM FMN, riboflavin or roseoflavin and the resulting products were separated by PAGE. Mutants are as described in the legend of Figure 3. Additional details are as described in the legend of Fig. 1C. (B) Plot of the band intensities at three sites where modulation is indicative of ligand binding as identified in (A) and in Fig. 1C. Site 4 was not included in the analysis due to the large signal from the nearby Pre band. Band intensities at each site were normalized to the NR lane so that no modulation is set to equal 1.

Overall, the patterns of spontaneous cleavage are somewhat different for each of the three mutant aptamer constructs compared to the WT construct. The M1 and M2 RNAs exhibit the greatest variation from the WT spontaneous cleavage pattern, suggesting that the point mutations carried by these RNAs cause folding problems. Most of the changes in spontaneous cleavage occur near the nucleotide that is mutated (positions 41 and 60 for M1 and M2, respectively). Unlike M1 and M2, the M3 RNA carries a mutation at nucleotide 133 that does not disrupt one of the base-paired stems of the secondary structure model, and this may explain why the mutation does not appear to cause much misfolding.

All three compounds trigger the WT RNA to exhibit robust modulation (Fig. 4B) at all sites noted previously5,10 (Fig. 1C) to undergo ligand-mediated changes. This is expected because the concentration of ligand used in each assay is near saturation even for the weakest-binding ligand, riboflavin. Although the mutant RNAs do exhibit some modulation of RNA structure when FMN is present, sites 1 through 3 show little measurable modulation when M1 and M2 mutant RNAs are exposed to roseoflavin or riboflavin. M3 shows near wild-type modulation at site 2 but little modulation is observed near sites 1 and 3 in the presence of riboflavin or roseoflavin. Notably, site 3 shows the least amount of modulation and this site is near the mutation carried by M3. These results indicate that all three mutations either adversely affect ligand binding affinity or alter the normal structural changes that are brought about by FMN binding. Either effect could disrupt riboswitch-mediated gene control in vivo.

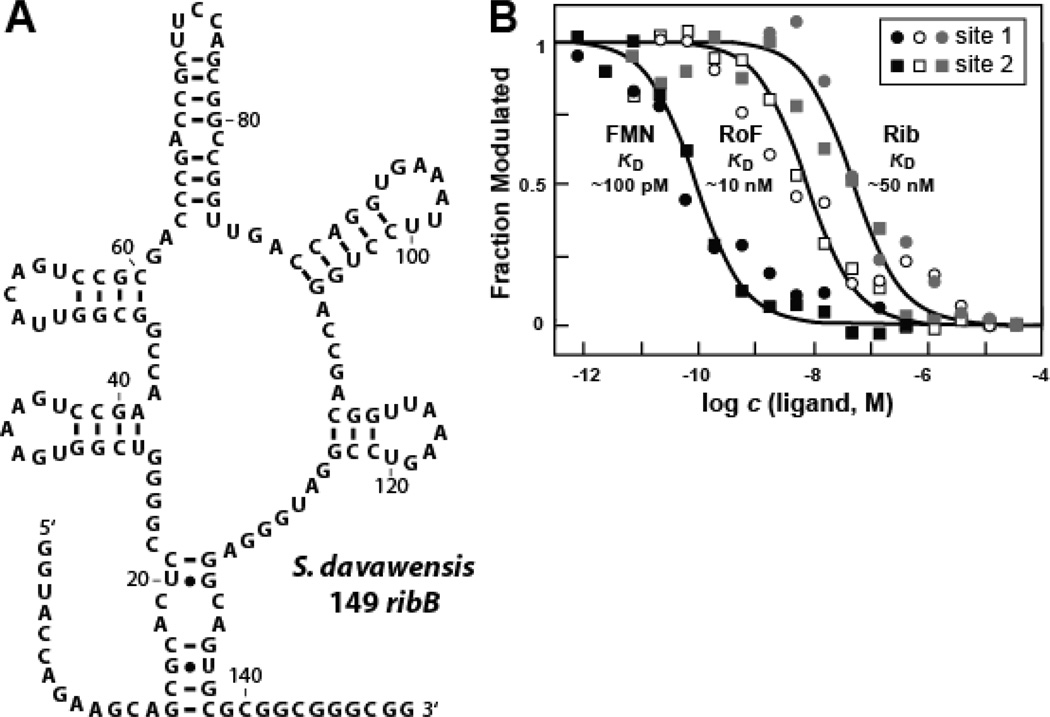

An FMN riboswitch in S. davawensis binds FMN, riboflavin and roseoflavin with high affinity

S. davawensis naturally produces roseoflavin and is resistant to this antibacterial compound,13,37 but the mechanism of resistance is still unknown. Interestingly, S. davawensis carries at least one sequence element that matches the consensus for FMN riboswitch aptamers. Specifically, we identified an FMN riboswitch sequence (Fig. 5A) in the 5′ UTR of an S. davawensis operon containing genes coding for riboflavin biosynthesis and transport proteins (ribB, ribM, ribA, ribH).38

Figure 5.

Ligand binding by an FMN riboswitch from S. davawensis. (A) RNA sequence and predicted secondary structure of the 149 ribB 5′ UTR from S. davawensis. (B) Plot of the normalized fraction of 149 ribB RNA modulated versus ligand concentration derived by in-line probing.

A 149-nucleotide RNA construct containing the S. davawensis FMN riboswitch (Fig. 5A) was subjected to in-line probing in the presence of various concentrations of FMN, riboflavin and roseoflavin. The apparent KD value for FMN was determined to be no poorer that 100 pM, and the KD values were found to be 50 nM and 10 nM for riboflavin and roseoflavin, respectively (Fig 5B). These values reveal that the S. davawensis FMN riboswitch does not selectively discriminate against roseoflavin under equilibrium conditions, and thus exhibits similar binding characteristics to those of the B. subtilis ribD aptamer (compare Fig. 1D and 5B). It is important to note, however, that we have not determined whether the S. davawensis FMN riboswitch can more substantially discriminate against roseoflavin phosphate, which might be the biologically relevant antimicrobial compound (see further discussion below).

Although the level of discrimination based on KD comparisons are similar between the S. davawensis and B. subtilis FMN riboswitch aptamers examined, our findings do not rule out the possibility that there is meaningful discrimination generated via different rate constants for ligand association. Several studies10,39–42 suggest that some riboswitches may be kinetically rather than thermodynamically driven. For example, tt has been shown that the B. subtilis ribD riboswitch does not reach thermodynamic equilibrium with FMN in a timeframe that is relevant for gene control.10 Rather, the riboswitch is kinetically driven, and therefore the rate constant for ligand association is more meaningful than the KD value when evaluating the concentration of ligand needed to trigger gene control. Barring kinetics-based discrimination or discrimination against a modified form of roseoflavin, S. davawensis does not appear to carry a specialized FMN riboswitch that specifically discriminates against roseoflavin. If true, S. davawensis would need to avoid deleterious inhibition of its own FMN biosynthetic genes by a mechanism that does not involve the use of a specialized FMN riboswitch that resists the action of roseoflavin.

Discussion

We have used a structural probing assay to confirm that roseoflavin binds to an FMN riboswitch from B. subtilis with high affinity (KD ~100 nM) in vitro (Fig. 1D). This finding is supported by recently generated structural models for an FMN riboswitch from Fusobacterium nucleatum bound to FMN, riboflavin and roseoflavin generated using x-ray crystallography data.22 The riboswitch binding pocket completely envelops FMN and makes numerous interactions with the pteridine ring, the ribityl moiety and the phosphate. Interactions with the ring structure of FMN are similar to the contacts made by the aptamer to riboflavin and roseoflavin. In contrast, the ribityl moiety of the latter compounds are not bound by the RNA in the same manner, but rather the binding pocket adapts its shape when binding riboflavin and roseoflavin. The loss of affinity for these non-phosphorylated compounds likely is due to the lack of the numerous interactions that are normally formed between the aptamer and the phosphate group of FMN.22

Although several nucleotides of the FMN riboswitch aptamer must protrude from the structure to accommodate the extra dimethylamine group of roseoflavin, the overall structure is very similar to that of the aptamer bound to riboflavin.22 Roseoflavin binds with a higher affinity than riboflavin despite the fact that riboswitch aptamer does not appear to form any bonds with the dimethylamine group of the antibacterial compound. The reason for this increased binding affinity is not clear, but it seems possible that more favorable interactions are formed elsewhere due to subtle structural rearrangements made to accommodate the dimethylamine group of roseoflavin. For example, in the crystal structure model, four hydrogen bonds are predicted to form between the aptamer and the ribityl moiety of riboflavin. However, five hydrogen bonds are formed between the aptamer and the ribityl of roseoflavin.22

Our findings also are consistent with the hypothesis that genes controlled by FMN riboswitches are essential for normal B. subtilis growth. When the B. subtilis ribD promoter and riboswitch were replaced with a xylose-inducible promoter, cells did not grow even in rich medium unless supplemented with xylose. Bacteria carrying the Pxyl-RS modification grew well during the first two hours after pelleting and resuspension in medium lacking xylose, but growth subsequently became stagnant (data not shown). This observation indicates that residual xylose, FMN, or riboflavin biosynthesis proteins allowed cells to continue normal growth until FMN reaches a growth-limiting concentration. Furthermore, the Pxyl promoter requires glucose supplementation to attain more complete inactivation of expression, and therefore low-level production of riboflavin synthesis proteins likely occurs. The same trend was seen when the Pxyl-RS strain is treated with glucose (Fig. 2), but growth was hampered further than that observed for the untreated bacteria. This is expected because glucose should further suppress expression from the Pxyl promoter.33

Most genes whose expression is controlled by wild-type FMN riboswitches are expected to be repressed in the presence of ligand. For the B. subtilis ribD riboswitch, this repression was almost completely lost (Fig. 3) in mutants identified in bacteria that have lost their sensitivity to roseoflavin. Furthermore, two (M1 and M2) of three mutant RNA aptamers examined exhibit substantial folding differences and disrupted structural modulation compared to the wild-type aptamer (Fig. 4). In-line probing of the M3 aptamer did not reveal any regions that were obviously misfolded, and two of the sites modulated with the same dissociation constant as the wild-type construct (data not shown). However, there was no significant modulation observed around site 3 (Fig. 4), which is near the G133A mutation that distinguishes this variant. In the atomic-resolution structural model for an FMN riboswitch aptamer, this mutation resides in the linker region between P5 and P6 that base pairs with a nucleotide in loop 3 and appears to support tertiary structure folding.22

Modulation of parts of the M3 riboswitch aptamer reflect the same KD as wild-type aptamers when thermodynamic equilibrium is achieved in an in-line probing assay. However, the loss of a tertiary contact in M3 may preclude the ligand-bound aptamer from controlling expression platform activity. Alternatively, the ligand may not bind to the mutant RNA with the same speed in vivo compared to the wild-type RNA. The ribD FMN riboswitch has been shown to be a kinetically driven riboswitch,10 so mutations that slow ligand binding could derepress gene expression. Such mechanisms of resistance may also explain why mutations to lysine riboswitches identified in lysine antimetabolite-resistant bacteria do not disrupt binding to lysine but still cause reduced gene repression.24

Although many roseoflavin-resistant strains of B. subtilis and some other Gram-positive bacteria have been identified and characterized, the mechanism of resistance to roseoflavin for the bacterium that produces it, S. davawensis, has not yet been elucidated. Previously identified bacterial mutants that resist roseoflavin toxicity usually carry mutations either in the ribD riboswitch or in the protein-coding region of the ribC gene.15–20 The ribC gene codes for a flavokinase/flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase. A recent study has shown that the proteins encoded by ribC in B. subtilis and S. davawensis phosphorylate both roseoflavin and riboflavin and no strong preference for riboflavin is observed in the S. davawensis protein.37 Therefore, selective phosphorylation of riboflavin versus roseoflavin does not appear to be the source of S. davawensis resistance to its own toxic compound.

The phosphate group of FMN forms several interactions with the FMN aptamer in the structural model.22 Consequently, there is reason to believe that phosphorylated roseoflavin could bind more tightly to the aptamer than the unphosphorylated form we tested. Since flavokinases from B. subtilis and S. davawensis can phosphorylate roseoflavin efficiently,37 it seems likely that the phosphorylated form of roseoflavin is the active form of the compound.

The emergence of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria is becoming a significant medical problem, and there is an increasing interest in the development of new antibacterial compounds. Recent findings of compounds that trigger riboswitch function in a diversity of bacterial cells21–24 offers evidence that some riboswitches may serve as useful targets for future antibiotic drug development efforts. We have considered FMN riboswitches a promising target for antibacterial compound development because they control important biosynthesis genes, they are widespread among bacteria and are found in numerous pathogens such as Bacillus anthracis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.21 Our findings in the current study are consistent with a role for FMN riboswitches in the antibacterial action of the riboflavin compound roseoflavin.

The recent atomic-resolution model for an FMN riboswitch aptamer22 also is consistent with our findings, and such models may provide a powerful tool for designing novel FMN analogs that target riboswitches. Already noteworthy is the observation that the binding site of the F. nucleatum FMN aptamer undergoes some rearrangement to accommodate roseoflavin and riboflavin. Such flexibility in the binding pockets of riboswitch aptamers could make the process of predicting novel analog designs inaccurate. However, this flexibility also creates more opportunities for finding analogs that otherwise would not be predicted to be recognized by the binding-site nucleotides if they rigidly remained in their FMN-bound configuration.

Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotides, Chemicals, Plasmids and Bacteria Strains

DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from either Sigma-Genosys or the W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at Yale University. Roseoflavin was purchased from MP Biomedicals. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. pDG1661, pMutin4, pSG1154, pBGSC6 and B. subtilis strain 1A1 were obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (Ohio State University). Competent DH5-alpha E. coli were purchased from New England Biolabs.

pDG1661 plasmid preparation

A 360-nucleotide fragment containing the ribD FMN riboswitch was amplified from the genomic DNA of B. subtilis strain 1A1 using mutagenic primers that added the promoter sequence from the B. subtilis lysC gene (TACGACAAATTGCAAAAATAATGTTGTC-CTTTTAAATAAGATCTGATAAAATGTGAACT) to the 5′ end as well as HindIII and BamHI restriction sites. The fragment was cloned into pDG1661 using the New England Biolabs (NEB) quick ligation kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Plasmid was transformed into competent E. coli DH5α cells and plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plates containing 100 µg/ml carbenicillin. Plasmid DNA was collected using a QIAGEN QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and was verified by DNA sequencing.

Two ~200-nucleotide fragments flanking the ribD FMN riboswitch region were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of B. subtilis strain 1A1. Primers designed for the region upstream of the ribD FMN riboswitch added XhoI and SpeI restriction sites and primers for the downstream region added HindIII and EcoRI sites. Inserts were cloned into pMXL3 sequentially and plasmid DNA was prepared and verified as described above.

pMXL3 plasmid preparation

pMXL3 was constructed using sections of pMutin4, pSG1154, and pBGSC6. pMutin4 was digested with AatII and EcoRV restriction endonucleases and the 1675 base-pair fragment containing the erm gene was isolated using agarose gel electrophoresis. pBGSC6 was digested with AatII and XbaI restriction endonucleases and the 3344 base-pair fragment containing the Cat and Bla genes was isolated using agarose gel electrophoresis. A region of pSG1154 containing a xylose-inducible promoter (Pxyl) was PCR amplified from pSG1154 using primers that incorporated restriction sites for EcoRV and HindIII at the termini (5´-TACGATATCTAGTGACATTTGCATGCTTC and 5´-CATAAGCTTTAGGAATCTCCTTTCTAGATGC; restriction sites are underlined). Following digestion with EcoRV and HindIII, a single fragment approximately 260 base pairs was isolated as described above. The agarose gel slices containing each of these three fragments were melted at 70°C for 5 minutes, combined, and ligated overnight using T4 polynucleotide kinase and buffer (New England Biolabs). The ligated plasmid, termed pMXL1, was transformed into competent E. coli DH5α cells and plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plates containing 100 µg/ml carbenicillin. Plasmid DNA was collected using a QIAGEN QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and was verified by DNA sequencing.

Through two subsequent rounds of cloning, new multiple cloning sites were ligated into pMXL1. Two complimentary oligos (5´-TCGACTCAAGCTTGTCGAATTCCTGAGGCGCCTCAGGATCCATGT and 5´-AAGCTACATGGATCCTGAGGCGCCTCAGGAATTCGACAAGCTTGAG) containing SalI, HindIII, EcoRI, KasI, HaeII, and BamHI sites were annealed and ligated with pMXL1 that had been digested with SalI and HindIII. The resulting plasmid was termed pMXL2. Finally, a section of pMXL1 was amplified with two primers (5´-TAGACGTCTTGGTACCATACTAGTCACTCGAGTAGAGCTCTGAAGAAAGCAGACAAGTAAGC and 5´-AGGGAATAAGGGCGACAC) complimentary to the region between the AatII and ClaI that incorporate new KpnI, SpeI, XhoI, and SacI restriction sites, and the resulting product was digested with AatII and ClaI, gel purified, and ligated with pMXL2 that had been digested with AatII and ClaI and gel purified. The identity of the final plasmid, pMXL3, was confirmed by DNA sequencing and restriction digest analysis.

RNA preparation

165 ribD template DNA was amplified by PCR from wild-type or mutant pDG1661 plasmid DNA. Primers used to amplify template DNA included the T7 promoter sequence at the 5′ end as well as two guanine residues added to increase the yield of transcribed RNA. DNA templates were incubated with T7 RNA polymerase in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0 at 23°C), 20 mM NaCl, 14 mM MgCl2, and 100 µM EDTA to produce RNA transcripts that were purified by employing denaturing (8 M urea) 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). RNAs were eluted from the gel by soaking gel fragments in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5 at 23°C), 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) overnight at 4°C or for 30 minutes at 23°C. RNAs were precipitated by the addition of 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol, the precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation, and the resulting RNA pellet was resuspended in water. RNAs were then dephosphorylated using calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Roche Diagnostics) and radiolabeled at the 5′ end using [γ-32P] ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Labeled RNAs were purified by denaturing 8% PAGE as described above.

S. davawensis ribB template DNA was made synthetically using two overlapping primers that covered the FMN riboswitch region and included the T7 promoter sequence and two additional guanine residues. Primers were purified by denaturing 8% PAGE and eluted from gel as described above. Primers were incubated with SuperScript™ II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s directions to obtain full-length ribB. RNA was transcribed from template DNA as described above.

In-line probing

In-line probing assays were performed essentially as described previously.29,30 Briefly, approximately 1 nM (B. subtilis ribD) or 50 pM (S. davawensis) of each 5′ radiolabeled RNA was incubated at 23°C for 40–48 hours in 20 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3 at 23°C) with flavin mononucleotide, riboflavin or roseoflavin at the concentrations indicated for each experiment. Denaturing 10% PAGE was used to separate RNA cleavage products and radiolabeled cleavage products were visualized using a Phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics). ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics) was used to quantify the product bands and this data was used to estimate the dissociation constant (KD) of ligands. The KD value was estimated by plotting the fraction modulated (F) versus the logarithm of the ligand concentration [L] at modulating sites and data was fit to the equation F = [L]/([L]+ KD) using SigmaPlot 9 (Systat Software). It was assumed that there is no modulation in the absence of ligand and complete modulation in the presence of the highest ligand concentration tested.

B. subtilis Pxyl-RS strain preparation

B. subtilis strain 1A1 was grown in 4 ml of transformation medium (25 g/L K2HPO4•3H2O, 6 g/L KH2PO4, 1 g/L trisodium citrate, 0.2 g/L MgSO4•7H2O, 2 g/L Na2SO4 (pH 7.0), 50 µM FeCl3, 2 µM MnSO4, 0.4% glucose, 0.2% glutamate, 50 µg/ml tryptophan). When cultures reached an A600 of ~0.8, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of transformation medium. Approximately 1 µg of the pMXL3 plasmid DNA described above was added and cultures were incubated with shaking at 37°C for 40 minutes. 2XYT (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) was added and cultures were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with shaking. Cultures were pelleted by centrifugation and spread on tryptose blood agar base (TBAB) plates containing 0.3 µg/ml erythromycin and 0.5% xylose. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and recombinants were identified by colony PCR amplification using primers that produced amplicons only if a double-crossover occurred.

B. subtilis WT and Pxyl-RS growth analysis

2XYT media was inoculated with B. subtilis WT and Pxyl-RS cells and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. 0.5% xylose was added to the medium for the Pxyl-RS strain because bacteria did not grow in 2XYT medium alone. Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of ~0.1 and grown at 37°C with shaking for approximately one hour. Cultures were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 8 ml of 2XYT medium before diluting to a final OD600 of approximately 0.01. Each strain was cultured in triplicate in a 96 well plate in the presence of medium alone, or supplemented with 0.5% xylose or 0.5% glucose. Absorbance at 595 nM was measured before sealing the plate with breathable sealing film and incubating at 37°C with shaking for 3 hours.

B. subtilis reporter strains

B. subtilis strain 1A1 was grown in transformation medium as described above. When cells reached an OD600 density of 0.4–0.8, approximately 0.5 µg of pDG1661 plasmid DNA was added to 1 ml of the culture. Cultures were incubated with shaking at 37°C for 40 minutes. 1 ml of 2XYT medium was added and cultures were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with shaking. 200 µl of the culture was spread on a TBAB plate containing 5 µg/ml chloramphenicol and grown overnight. Transforming pDG1661 in B. subtilis inserted the FMN riboswitch and lacZ reporter gene directly into the B. subtilis genome in the amyE locus by double-crossover recombination. Single colonies were screened for double-crossover events by testing for sensitivity to 100 µg/ml spectinomycin.

β-galactosidase Assays

B. subtilis 1A1 reporter strains were grown overnight in 2XYT medium with 5 µg/ml chloramphenicol at 37°C with shaking. Cultures were diluted to an OD600 of ~0.2 and grown for about two hours at 37°C with shaking. Bacterial cultures were pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant was discarded. Cultures were resuspended in glucose minimal medium and diluted to an OD600 of ~0.7. Bacterial cultures were grown in duplicate or triplicate with no compound, 100 µM riboflavin or 100 µM roseoflavin at 37°C with shaking for 2 to 3 hours. Cultures were washed with Z buffer without β-mercaptoethanol (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, pH 7.0 at 23°C) 4–5 times to remove riboflavin and roseoflavin before performing β-galactosidase assays using the standard protocol.43

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Zheng for assistance on this project and members of the Breaker laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH award U54AI57158 (Northeast Biodefense Center--Lipkin) and by NIH grants (R33 DK07027 and GM 068819) to R.R.B. E.R.L was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32GM007223). Research in the Breaker laboratory is also supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- ribD

ribDEAHT operon

- Rib

riboflavin

- RoF

roseoflavin

- TPP

thiamin pyrophosphate

- UTR

untranslated region

References

- 1.Coppins RL, Hall KB, Groisman EA. The intricate world of riboswitches. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandal M, Breaker RR. Gene regulation by riboswitches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:451–463. doi: 10.1038/nrm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soukup JK, Soukup GA. Riboswitches exert genetic control through metabolite-induced conformational change. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Regulation of bacterial gene expression by riboswitches. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15908–15913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212628899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mironov AS, Gusarov I, Rafikov R, Lopez LE, Shatalin K, Kreneva RA, Perumov DA, Nudler E. Sensing small molecules by nascent RNA: a mechanism to control transcription in bacteria. Cell. 2002;111:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Jomantas J, Kozlov YI, Perumov DA. A conserved RNA structure element involved in the regulation of bacterial riboflavin synthesis genes. Trends Genet. 1999;15:439–442. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack M, van Loon AP, Hohmann HP. Regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis is affected by the activity of the flavokinase/flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase encoded by ribC . J Bacteriol. 1998;180:950–955. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.950-955.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JM, Zhang S, Saha S, Santa Anna S, Jiang C, Perkins J. RNA expression analysis using an antisense Bacillus subtilis genome array. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7371–7380. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7371-7380.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol Cell. 2005;18:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogl C, Grill S, Schilling O, Stülke J, Mack M, Stolz J. Characterization of Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) Transport Proteins from Bacillus subtilis and Corynebacterium glutamicum . J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7367–7375. doi: 10.1128/JB.00590-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreneva RA, Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Yomantas JA, Kozlov YI, Mironov AS, Perumov DA. Study of the phenotypic occurrence of ypaA gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Russ J Genet. 2000;36:972–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otani S, Takatsu M, Nakano M, Kasai S, Miura R. Letter: Roseoflavin, a new antimicrobial pigment from Streptomyces . J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1974;27:86–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otani S, Kasai S, Matsui K. Isolation, chemical synthesis, and properties of roseoflavin. Methods Enzymol. 1980;66:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(80)66464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kil YV, Mironov VN, Gorishin IY, Kreneva RA, Perumov DA. Riboflavin operon of Bacillus subtilis: unusual symmetric arrangement of the regulatory region. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:483–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00265448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreneva RA, Perumov DA. Genetic mapping of regulatory mutations of Bacillus subtilis riboflavin operon. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:467–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00633858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kukanova A, Zhdanov VG, Stepanov AI. Bacillus subtilis mutants resistant to roseoflavin. Genetika. 1982;18:319–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sybesma W, Burgess C, Starrenburg M, van Sinderen D, Hugenholtz J. Multivitamin production in Lactococcus lactis using metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2004;6:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsui K, Wang HC, Hirota T, Matsukawa H, Kasai S, Shinagawa K, Otani S. Riboflavin production by roseoflavin-resistant strains of some bacteria. Agric Biol Chem. 1982;46:2003–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgess CM, O’Connell-Motherway M, Sybesma W, Hugenholtz J, van Sinderen D. Riboflavin production in Lactococcus lactis: potential for in situ production of vitamin-enriched foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:5769–5777. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5769-5777.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blount KF, Breaker RR. Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1558–1564. doi: 10.1038/nbt1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serganov A, Huang L, Patel DJ. Molecular insights into coenzyme recognition and gene regulation by a FMN riboswitch. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature07642. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudarsan N, Cohen-Chalamish S, Nakamura S, Emilsson GM, Breaker RR. Thiamine pyrophosphate riboswitches are targets for the antimicrobial compound pyrithiamine. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1325–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blount KF, Wang JX, Lim J, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. Antibacterial lysine analogs that target lysine riboswitches. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:44–49. doi: 10.1038/nchembio842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serganov A, Huang L, Patel DJ. Structural insights into amino acid binding and gene control by a lysine riboswitch. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07326. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serganov A, Polonskaia A, Phan AT, Breaker RR, Patel DJ. Structural basis for gene regulation by a thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitch. Nature. 2006;441:1167–1171. doi: 10.1038/nature04740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards TE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Crystal structures of the thi-box riboswitch bound to thiamine pyrophosphate analogs reveal adaptive RNA-small molecule recognition. Structure. 2006;14:1459–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thore S, Frick C, Ban N. Structural basis of thiamine pyrophosphate analogues binding to the eukaryotic riboswitch. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8116–8117. doi: 10.1021/ja801708e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA. 1999;5:1308–1325. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regulski EE, Breaker RR. In-line probing analysis of riboswitches. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;419:53–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-033-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandal M, Lee M, Barrick JE, Weinberg Z, Emilsson GM, Ruzzo WL, Breaker RR. A glycine-dependent riboswitch that uses cooperative binding to control gene expression. Science. 2004;306:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1100829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welz R, Breaker RR. Ligand binding and gene control characteristics of tandem riboswitches in Bacillus anthracis . RNA. 2007;13:573–582. doi: 10.1261/rna.407707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus A, Hueck C, Gartner D, Hillen W. Catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis xyl operon involves a cis element functional in the context of an unrelated sequence, and glucose exerts additional xylR-dependent repression. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1738–1745. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1738-1745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerdes SY, Scholle MD, D’Souza M, Bernal A, Baev MV, Farrell M, et al. From genetic footprinting to antimicrobial drug targets: examples in cofactor biosynthetic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 2002:4555–4572. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4555-4572.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudarsan N, Wickiser JK, Nakamura S, Ebert MS, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure in bacteria that controls gene expression by binding lysine. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2688–2697. doi: 10.1101/gad.1140003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudarsan N, Lee ER, Weinberg Z, Moy RH, Kim JN, Link KH, Breaker RR. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2008;321:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1159519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grill S, Busenbender S, Pfeiffer M, Köhler U, Mack M. The bifunctional flavokinase/flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase from Streptomyces davawensis produces inactive flavin cofactors and is not involved in resistance to the antibiotic roseoflavin. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1546–1553. doi: 10.1128/JB.01586-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grill S, Yamaguchi H, Wagner H, Zwahlen L, Kusch U, Mack M. Identification and characterization of two Streptomyces davawensis riboflavin biosynthesis gene clusters. Arch Microbiol. 2007;188:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wickiser JK, Cheah MT, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The kinetics of ligand binding by an adenine-sensing riboswitch. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13404–13414. doi: 10.1021/bi051008u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert SD, Stoddard CD, Wise SJ, Batey RT. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of ligand binding to the purine riboswitch aptamer domain. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:754–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rieder R, Lang K, Graber D, Micura R. Ligand-induced folding of the adenosine deaminase A-riboswitch and implications on riboswitch translational control. Chembiochem. 2007;8:896–902. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lang K, Rieder R, Micura R. Ligand-induced folding of the thiM TPP riboswitch investigated by a structure-based fluorescence spectroscopic approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5370–5378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller JH. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 72–80. [Google Scholar]