Abstract

The ubiquitin ligase Highwire has a conserved role in synapse formation. Here, we show that Highwire coordinates several facets of central synapse formation in the Drosophila melanogaster giant fiber system, including axon termination, axon pruning, and synaptic function. Despite the similarities to the fly neuromuscular junction, the role of Highwire and the underlying signaling pathways are distinct in the fly’s giant fiber system. During development, branching of the giant fiber presynaptic terminal occurs and, normally, the transient branches are pruned away. However, in highwire mutants these ectopic branches persist, indicating that Highwire promotes axon pruning. highwire mutants also exhibit defects in synaptic function. Highwire promotes axon pruning and synaptic function cell-autonomously by attenuating a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway including Wallenda, c-Jun N-terminal kinase/Basket, and the transcription factor Jun. We also show a novel role for Highwire in non-cell autonomous promotion of synaptic function from the midline glia. Highwire also regulates axon termination in the giant fibers, as highwire mutant axons exhibit severe overgrowth beyond the pruning defect. This excessive axon growth is increased by manipulating Fos expression in the cells surrounding the giant fiber terminal, suggesting that Fos regulates a trans-synaptic signal that promotes giant fiber axon growth.

Keywords: synaptogenesis, giant fiber, pruning, highwire, Fos

HIGHWIRE (Hiw) is an extremely large, conserved protein that contains an N-terminal guanosine triphosphate exchange factor-like domain (Wan et al. 2000; Zhen et al. 2000), two PHR repeats, a myc-binding domain (Guo et al. 1998), and a RING (really interesting new gene) finger domain for ubiquitin E3 ligase activity (Wan et al. 2000). The cell-autonomous role for Hiw in synaptic development is also well-conserved. The mouse ortholog PHR-1 is required for neuromuscular junction (NMJ) and sensory neuron development (Burgess et al. 2004). The zebrafish ortholog, Esrom, is critical for visual system organization (D’Souza et al. 2005). Finally, in Caenorhabditis elegans, RPM-1/Hiw is required for organization of presynaptic terminals in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic motor neurons and axon termination in mechanosensory neurons (Zhen et al. 2000; Nakata et al. 2005).

In Drosophila, the ligase activity of Hiw is required for proper synapse development; hiw mutants show overgrown axons and weakened synaptic function (Wan et al. 2000; Wu et al. 2005). Hiw is responsible for ubiquitinating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Wallenda (Wnd), allowing for proper NMJ development (Nakata et al. 2005; Collins et al. 2006), as shown by the fact that hiw mutants are rescued by knocking down Wnd, or its downstream targets/effectors. This interaction between Hiw and Wnd is conserved in worms (Fulga and Van Vactor 2008), where the C. elegans ortholog RPM-1/Hiw is required for proper connection of the SAB cholinergic axons by downregulation of the kinase DLK-1 (Abrams et al. 2008). Hiw, the Wnd MAPK cascade, and the transcription factors Fos and Jun are critical for several axonal processes: growth (Chang et al. 2003; Bloom et al. 2007; Lewcock et al. 2007; Hartwig et al. 2008; Rallis et al. 2010), maintenance (Chang et al. 2003; Miller et al. 2009; Ghosh et al. 2011; Rallis et al. 2013), and axon injury response (Hammarlund et al. 2009; Xiong et al. 2010, 2012; Shin et al. 2012; Xiong and Collins 2012).

Hiw was first analyzed in the Drosophila giant fiber system (GFS) as a potential downstream effector of the E2 conjugase known as Bendless, but was found to work independently of Bendless (Uthaman et al. 2008). However, hiw mutants showed severely disrupted synaptic transmission and overgrown axon terminals, warranting the present study. The normal development of the giant fiber synapse during pupal development (PD) includes the removal of transient extraneous axon branches, described anecdotally in early studies (Phelan et al. 1996; Allen et al. 1998) and in more detail in the present study. Giant synapse development includes formation of an electrochemical synapse with the target motorneuron (Tergorochanteral Motor neuron, TTMn). Here, we investigate the role of Hiw in establishing this connection, both structurally and functionally.

In this study, we show that Hiw is required presynaptically for proper synaptic function. We also reveal a novel non-cell autonomous role for Hiw in the midline glia to promote synaptic function of the giant synapse. As at the NMJ (Collins et al. 2006), Hiw functions in the giant fibers (GFs) by downregulating the MAPK cascade, including Wnd and Bsk. This central synapse differs from the NMJ in several ways: (1) the transcription factor output of the MAPK cascade is Jun, not Fos; (2) the MAPK pathway affects both the structure and function of the GFS; and (3) attenuation of the MAPK pathway by Hiw in the GFS promotes axon pruning. Finally, we show that Hiw also regulates axon termination and reveal that Fos expression in the midline glia and postsynaptic TTMn influences trans-synaptic signaling to the GFs.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks

All stocks were grown at 22°, or 25° where noted, on standard medium (Genesee). The hiwND8 line has been described previously (Wan et al. 2000). The following fly stocks were graciously provided by Cathy Collins (University of Michigan): UAS-Bsk RNAi (RNA interference) (Vienna stock #34138), wnd1, bsk1, UAS-bskDN (Weber et al. 2000; Collins et al. 2006), UAS-FosDN (Eresh et al. 1997), UAS-JunDN (Eresh et al. 1997), UAS-Wnd, UAS-Hiw, and UAS-hiwΔRING (Collins et al. 2006). UAS-FosRNAi (Dirk Bohmann, on II) was kindly provided by Subhabrata Sanyal (Biogen). We obtained the following lines from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: (fos) kayEY12710 (20843), junIA109 (3273), UAS-Bsk (9310), UAS-Fos (7213), and Mkk4e01485 (17956). We initially used the fos mutant kay1, but due to concerns about other mutations in the line, we used the kayEY12710 p-element disruption mutant, hereafter referred to as fosEY12710 (Zeitlinger et al. 1997; Bellen et al. 2004). Because hiw is on the X chromosome, we used males for all of our experiments to avoid any issue with dosage compensation.

Targeted expression was achieved by using the UAS-GAL4 system (Brand and Perrimon 1993). The P[GAL]4 lines that allow GFS-specific expression were: P[GAL4] A307-GAL4 (hereafter referred to as the A307 driver), which expresses strongly in the GFs and postsynaptic TTMns (Allen et al. 1998); P[GAL4] C17-GAL4 (hereafter referred to as the C17 driver), which expresses in midline glia from 0 to 32% of PD and presynaptically in the GF from 32% of PD through adulthood (Orr et al. 2014); and P[GAL4] shakB(lethal)-GAL4 (hereafter referred to as the ShkB driver), which expresses postsynaptically (TTMn) through PD to adult (Jacobs et al. 2000). P[GAL4] C42.2-GAL4 (hereafter referred to as the C42.2 driver) expresses in the GFs starting at 50% PD, after giant synapse formation. P[GAL4] slit-GAL4 (hereafter referred to as the Slit driver) was also used to express in the midline glia. A recently acquired line that expresses in the GFs throughout PD and through adulthood was P[GAL4] R91H05-Gal4 (Jenett et al. 2012); it was recombined with UAS-GFP, courtesy of Tanja Godenschwege (Florida Atlantic University), to image GF development (hereafter referred to as R91H05-GFP). We compared hiwND8 males to hiwND8 males combined with each driver used in rescue experiments (sibling controls: hiwND8/>; A307/+, hiwND8/>; C17/+, hiwND8/>; ShkB/+, hiwND8/>; +/+; Slit/+, hiwND8/>; +/+; C42.2/+, and hiwND8/>; +/+; R91H05-GFP/+). There was no difference between the hiw mutants and any of the controls. Therefore, for ease of reading, we showed comparisons to hiwND8 throughout this manuscript.

Electrophysiological intracellular recordings measuring circuit output

Flies between 4 and 10 days posteclosion were anesthetized with CO2 and placed in dental wax ventral side down. Intracellular excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) recordings were obtained from the tergotrochanteral jump muscle (TTM) or dorsal longitudinal flight muscle (DLM) by inserting a glass microelectrode with a resistance of 40–60 ΜΩ, backfilled with O’Dowd’s saline (Tanouye and Wyman 1980; Allen and Godenschwege 2010; Augustin et al. 2011). Here, we reported only the TTM results. GFs were stimulated extracellularly via tungsten wire electrodes placed in the eyes (Figure 1B) using a Grass S48 stimulator (Grass Technologies). Signals were amplified with a Getting 5A amplifier (Getting Instruments). An Axon Digidata 1440A Data Acquisition System was used to digitalize the data and recordings were collected with Clampex software (Molecular Devices). We measured three parameters to test the fidelity of the circuit: response latency and following frequencies at 100 and 200 Hz. Physiological phenotypes were reported as percent wild-type (% WT). A TTM response latency longer than 1 msec was considered a mutant response. TTM following frequencies were considered mutant if < 80% of stimuli responded with an EPSP at 100 HZ and < 70% at 200 Hz.

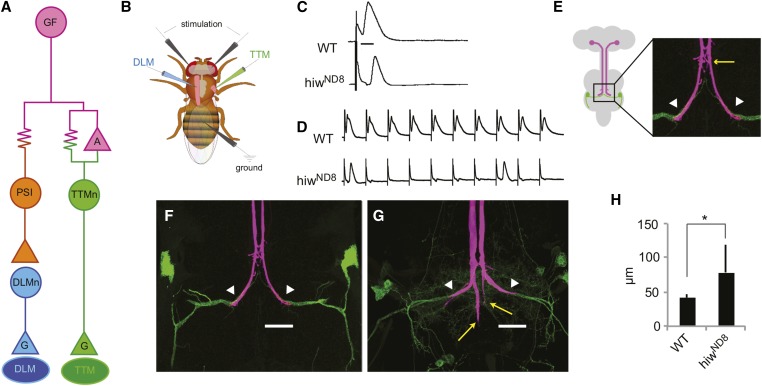

Figure 1.

Highwire in the giant fiber system. (A) Circuit diagram of the GFS. The GF (magenta) commands two motor outputs. The GF forms both gap junctions (resistor symbol) and cholinergic synapses (magenta triangle “A”) with the TTMn (green), which innervates the TTM “jump” muscle (dark green oval) with a glutamatergic synapse (triangle “G”). For the DLM flight pathway, the GF electrically synapses with the PSI (orange), an interneuron that synapses cholinergically with the DLMn (blue), which innervates the DLM “flight” muscle (dark blue oval). (B) Schematic of electrophysiology experiment. Extracellular stimulating electrodes are placed in the brain, recording electrodes in the TTM and DLM muscles, and a ground in the abdomen. The location of the CNS is shown in gray. (C) Recordings from the TTM illustrate the response latencies of TTM to brain stimulation. Calibration bar = 2 msec. Top trace shows a WT response latency of ∼0.8 msec. Bottom trace shows hiwND8 response latency is 1.69 msec, about double that of WT. (D) Single sweeps illustrate response to repetitive stimulation at 100 Hz. Top trace is WT and each stimulus is followed by a response. Bottom trace shows hiwND8, which does not follow high-frequency stimulation 1:1. In this case, the TTM only responded after the first and eighth stimuli. (E) Anatomy of the GF system. Schematic representation of the fly CNS, showing location of GFs (magenta) and TTMn (green). The presynaptic terminal in the second thoracic neuromere (box) is shown as a confocal image. The site of the GF:PSI synapse (yellow arrow) is used as the starting point to measure the length of the axon terminal and the white arrowhead as the end of the terminal. (F) WT GF axon terminals (magenta and white arrowheads) synapsing with TTMn medial dendrites (green). The TTMn somata are shown at the edge of the frame. (G) Mutant hiwND8 GF axons synapse with TTMn, but project ectopic branches caudally past the target (yellow arrows). (H) Average terminal length of WT and hiwND8 mutants. The average length of hiwND8 terminal measured as in E is nearly double the length of the WT terminal, due to the ectopic branching. DLM, dorsal longitudinal flight muscle; DLMn, DLM neuron; GF, giant fiber; GFS, GF system; TTM, tergotrochanteral jump muscle; TTMn, TTM neuron; PSI, Peripherally Synapsing Interneuron; WT, wild-type.

Dye injection and GFS imaging

Nervous systems of 4–10 day posteclosion adult flies were removed and mounted in O’Dowd’s saline on a glass slide coated with Poly-L-Lysine. Using a 40 × water immersion objective and DIC optics, the GF was located in the neck connective, impaled, and injected with Lucifer Yellow (backfilled with 3 M LiCl) using hyperpolarizing current (Uthaman et al. 2008; Boerner and Godenschwege 2011).

A Nikon DS-Qi1 camera and Nikon Elements software (Nikon, Garden City, NY) were used to acquire fluorescent image stacks. ImageJ Background Subtraction was used on fluorescent images. For confocal imaging of the GFS, GFs were filled with a cocktail of neurobiotin and rhodamine dextran (backfilled with 3 M KOAc) using depolarizing current. The dextran labels the GF, while the neurobiotin crosses gap junctions and also labels postsynaptic cells that are dye-coupled to the GFs. Samples were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Neurobiotin signal was visualized by binding streptavidin conjugated to a fluorophore, either Cy2 or Dylight 649 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Samples were examined by confocal microscopy (Boerner and Godenschwege 2011). Confocal images were obtained with a Nikon C1 confocal microscope using Nikon EZ-C1 software; confocal image analysis was performed with Nikon Elements.

Examining GF development during PD

Pupal central nervous systems (CNS) of animals expressing GFP in the GFs (R91H05-GFP) were dissected at time points before, during, and after GF to TTMn synapse development, between ∼25 and 75% of PD. We used both dye injection (as described above) and antibody staining of GFP to image developing GFs. Rabbit anti-GFP (diluted 1:500) (Vector Laboratories) antibodies and anti-Rabbit-Cy2 (diluted 1:500) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used to enhance the GFP signal for confocal imaging. Animals were raised at 25° because PD occurs over 100 hr at 25°. Hours after puparium formation and %PD were interchangeable.

Measuring axon terminal lengths

Measurements of GF axon terminal lengths were obtained from tiff stacks of fluorescence images and analyzed using Simple Neurite Tracer (Fiji) (Longair et al. 2011). The region of the GF to peripherally synapsing interneuron (PSI) synapse, rostrally located to the GF to TTMn synapse, was used as the starting point for measurement. Calibration for each fluorescence image (40 ×) collected with the Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera and Nikon Elements was 0.16 µm/pixel. For each experimental genotype, we compared males to hiwND8 males.

Statistical analysis

We used Fisher’s Exact test to compare two genotypes with values reported as % WT. We considered significance at P ≤ 0.05 for Fisher’s Exact comparisons. A two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance showed significance between average terminal lengths measured with Simple Neurite Tracer; significance was considered at P ≤ 0.05. All comparisons were to hiwND8 mutants, unless otherwise noted. Average response latencies and following frequencies between hiwND8mutants and select genotypes were also analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance.

Data availability

Strains are available upon request. The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.

Results

The hiwND8 allele produces defects in axon pruning and synaptic function

The hiwND8 mutants exhibited defects in synaptic structure and function. Anatomically, the hiwND8 allele resulted in two types of axon termination defects in the GFs. The typical defect, seen in 62.5% of the hiwND8 GF terminals, was an extra branch growing caudally past the synapse (Figure 1G, arrows). The normal bend of the terminal along the TTMn dendrite where the GF forms its synapse was still present (Figure 1, F and G, arrowheads) in all but 6.94% of GFs, which exhibited the “bendless” phenotype (Figure 2, B, E, and G) (Uthaman et al. 2008). We measured the average length of the axon terminal posterior to the PSI synapse (Figure 1E) to compare the hiwND8 to the WT. The average length of a WT (Urbana-S, n = 19) terminal was 41.85 μm, while hiwND8 terminals including a caudal branch were significantly longer measuring 78.55 μm (P = 0.0003) (Figure 1H).

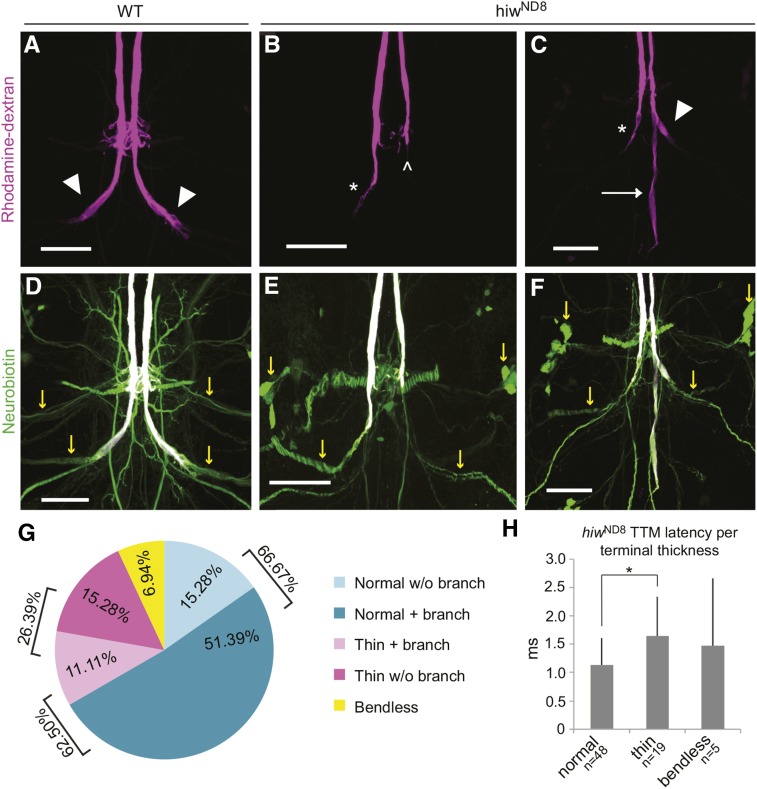

Figure 2.

Anatomical and physiological hiwND8 phenotypes. (A–C) Rhodamine dextran-filled GF terminals. (A) WT Urbana-S shows terminals of normal thickness (arrowheads). (B and C) The characteristic hiwND8 mutant phenotype exhibits caudal branches (C, arrow). Some specimens occasionally exhibit “bendless” terminals (B, carrot) and terminals that are thinner than normal (B and C, asterisks). (D–F) Neurobiotin/Rhodamine dextran colabeling of the same preparations used in A–C. Neurobiotin (green) shows colabeling with Rhodamine dextran (white) in the GFs. In D, Urbana-S shows normal dye coupling, as neurobiotin (green) fills TTMn and PSI neurons (yellow arrows). Despite morphological and physiological defects, hiwND8 mutant GFs dye couple to TTMn and PSI (E and F, yellow arrows), demonstrating that synaptic function defects are not due to missing gap junctions. (G) Distribution of male hiwND8 axon terminal thickness per phenotype (n = 72). WT refers to GFs without the caudal branch. “Branch” refers to caudal branch. “Normal,” “thin,” and “bendless” refer to the thickness of the terminal. 26.39% of hiwND8 terminals are thin. The presence of the caudal branch is not correlated with the thin terminal phenotype; 62.5% (n = 45) of males exhibit the caudal branch and only 17.78% (n = 8) of those males have thin terminals. Terminal thickness is normal in 66.67% of hiwND8 male GFs. Thus, we focus on the caudal branch as the strong anatomical phenotype of hiwND8. (H) Average TTM response latencies of normal, bendless, and thin GFs of hiwND8 males (n = 72). While all have longer than WT latencies, thin GFs (26.39% of terminals) have a significantly longer average TTM response latency compared to the normal sized terminals (66.67% of terminals). This suggests impedance mismatch as a possible cause of severe latency defects. GF, giant fiber; TTM, tergotrochanteral jump muscle; TTMn, TTM neuron; PSI, Peripherally Synapsing Interneuron; WT, wild-type.

Physiologically, the hiwND8 allele severely disrupts synaptic function (Figure 1, C and D), as only 20.83% of GFs were WT (n = 72 and P = < 0.0001). The average TTM response latency increased from the WT latency of 0.87 msec to the mutant latency of 1.29 msec (P = < 0.0001) (Figure 1C). The ability of the TTM to respond to 100 and 200 Hz stimulation dropped to an average of 51.6 and 38.95%, respectively, compared to 99 and 98% in WT animals (P = < 0.0001 and P = < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 1D).

The GF to TTMn synapse is a mixed electrical and cholinergic synapse, with the gap junctions dominating the synapse (Phelan et al. 1996; Allen et al. 1998; Allen and Godenschwege 2010). We injected neurobiotin into the GFs to assess dye coupling, which indicates an electrical connection (Figure 2, D–F, yellow arrows). Mutant hiwND8 GFs always dye-coupled to the TTMn and other local interneurons, suggesting that the physiological defect was not due to a complete failure to form gap junctions.

In addition to the caudal branch, we scored GF terminal widths as normal, thin, or bendless (Figure 2, G and H). Of all hiwND8 terminals, 66.67% had normal diameters, 26.39% were thin, and 6.94% were bendless (Figure 2G). When the response latencies of normal and thin terminals were compared, a significant increase in the average TTM response latency from a mildly mutant 1.13 msec to a more severe 1.64 msec (P = 0.009) was observed. These physiological defects could be the result of an impedance mismatch between the GF and TTMn. The presence of thin terminals was not linked to the presence of the caudal branch; only 11.11% of all terminals had both thin terminals and a caudal branch (Figure 2G), suggesting that structure and function are not directly linked.

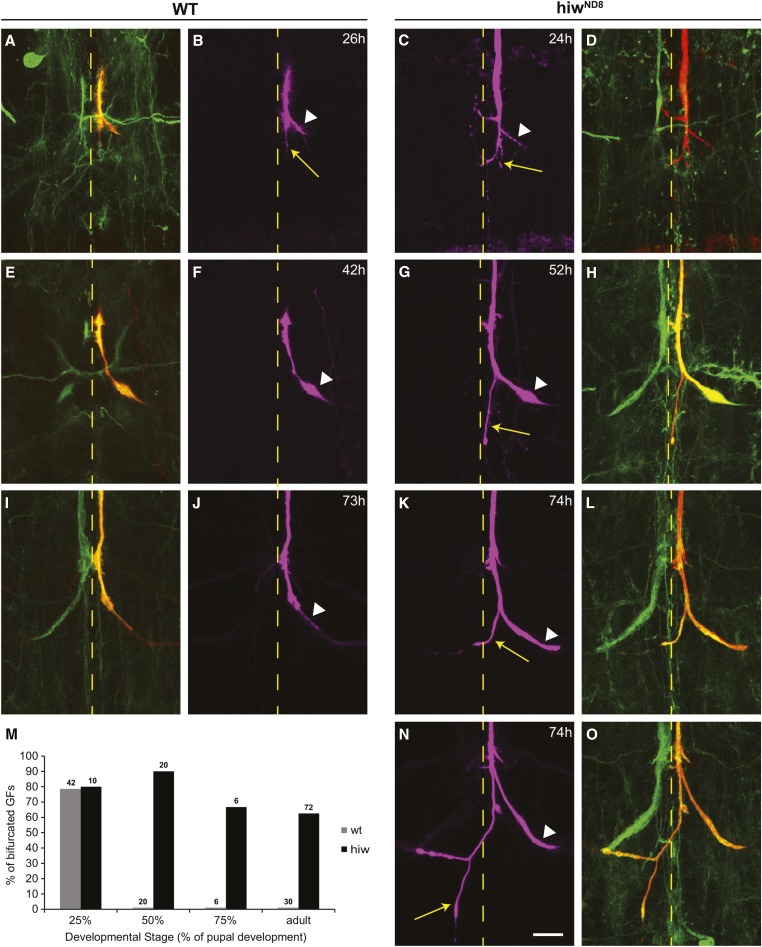

Caudal branches in hiwND8 mutants mirror developmentally transient branches

The ectopic branching of the GF axon terminal in hiwND8 animals is reminiscent of the transient branching occasionally reported in WT GFs during PD (Phelan et al. 1996). We characterized this transient branching in WT and hiwND8 animals with a new GAL4 line with GF-specific expression during PD (R91H05-GFP; Jenett et al. 2012). By ∼25% of PD, the GFs have formed the synaptic terminal and the caudal branch, seen in both WT and hiwND8 mutants (Figure 3, A–D and M). By ∼50% PD, WT GFs have lost the caudal branch and resemble WT adult morphology (Figure 3, E, F, and M). However, hiwND8 mutants retain the caudal branch at 50% PD and maintain it throughout the rest of PD and into adulthood (Figure 3, G, H, and M). In brief, in WT specimens, the overgrowth peaks at ∼25% of PD and is retracted by 50% of PD (Figure 3M). Because of the similarity between the transient branches in WT pupae and the hiwND8 mutant caudal branches, we suggest that Hiw is regulating the developmental pruning of the transient caudal branch.

Figure 3.

Axon growth and refinement during PD. Left two columns illustrate WT terminals at various stages of development. (A and B) At ∼25% of development, the axon has reached the target area, appears to be in contact with the TTMn dendrite (white arrow head), but also exhibits extra branches projecting posteriorly (yellow arrow). (E and F) By 45% of development (I and J), the excess branching has been eliminated and the presynaptic terminal is readily identified (arrowhead). At ∼75% of PD, the terminals appear very similar to the adult terminal (arrowhead). The two right columns illustrate Hiw terminals at various stages of development. (C and D) At 25% of development, the terminals exhibit excess branching and are very similar to the wild-type terminals. (G and H) At ∼45% of PD, the lack of pruning is clear in the hiwND8 and the mutant extension is obvious (yellow arrow). (K and L, and N and O) at ∼75% of PD the excess branching (arrow) is still present. These two examples illustrate the variability because the left GF (labeled by GFP) appears normal, but the dye-injected right GF exhibits excess branching as well as crossing the midline (yellow arrows). (M) Overgrowth and retraction of the GF terminal in control and mutant animals. Note the excess branching is at the peak in WT at ∼25% and most branches are retracted by 50%. The excess branching persists throughout development in the mutant. All animals were raised at 25°; at this temperature, PD occurs in 100 hr, making hours and % of PD interchangeable. GF, giant fiber; PD, pupal development; WT, wild-type.

It is important to note that a small percentage (∼10%) of hiwND8 GFs grow beyond the typical caudal branch. The caudal branch may grow much farther into the third thoracic and abdominal neuromeres. In this small group of animals, it is common to see tertiary branching as well (Figure 3, N and O). This excessive growth signifies that in addition to failed pruning of the transient branch, axon termination fails and the GF axons continue to grow. We predict that the low numbers of hiwND8 mutant GFs with excessive axon growth are due to stochastic expression of guidance cues that promote axon growth. Below, we describe scenarios where we increased the excessive axon growth in hiwND8 mutants by altering expression of two transcription factors in the cells surrounding the GF terminal, likely altering the levels of secreted guidance cues and highlighting Hiw’s role in axon termination.

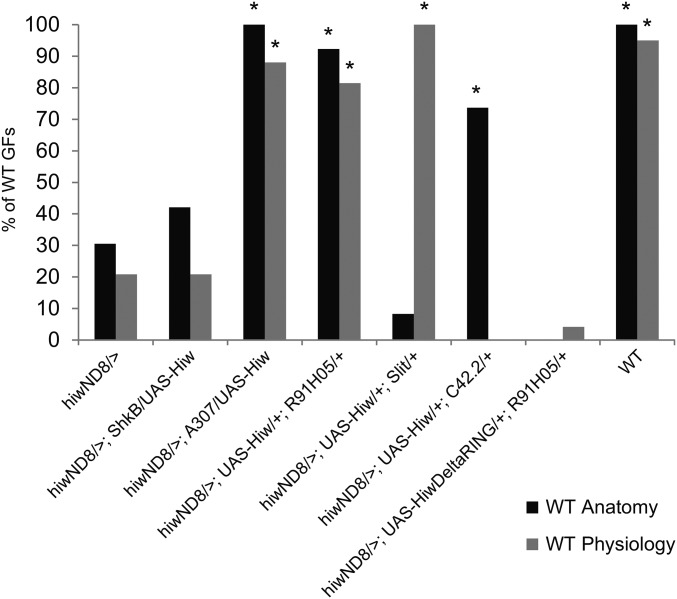

Tissue-specific requirements for Hiw

To determine in which cells Hiw functions, we expressed UAS-Hiw using a variety of Gal4 drivers in a hiw mutant background (Figure 4). Expressing UAS-Hiw presynaptically in hiwND8 males (hiwND8/>; UAS-Hiw/+; R91H05/+) completely rescued GF anatomy (n = 26, 92.31% WT, and P = < 0.0001) and nearly all (81.48%) GFs had normal WT synaptic function (n = 27 and P = < 0.0001). Simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic expression (hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-Hiw, n = 11) also rescued structure (100% WT) and function (88% WT). In contrast, postsynaptic expression of Hiw (hiwND8/>; ShkB/UAS-Hiw) did not rescue either the hiwND8 anatomical phenotype (n = 19, 42% WT, and P = 0.413) or synaptic function (n = 24, 20.83% WT, and P = 1.0). Finally, midline glial expression of Hiw (hiwND8/>; UAS-Hiw/+; Slit/+) did not rescue hiwND8 axon terminal morphology (n = 12, 8.33% WT, and P = 0.1656) (Figure 4). However, synaptic function was completely rescued (n = 12, 100% WT, and P = < 0.0001 vs. hiwND8). Apparently, Hiw plays both a cell-autonomous role in the GF to regulate structure and a non-cell autonomous role in the glia to regulate synaptic function.

Figure 4.

The rescue of hiwND8 phenotypes by tissue-specific expression of UAS-Hiw. The presynaptic expression of UAS-Hiw by the R91H05 driver significantly rescued both structure and function. Postsynaptic expression with the ShkB driver did not rescue either structure or function. Midline glial expression (Slit driver) rescued synaptic function, but not axon structure, revealing a non-cell autonomous role for Hiw in synaptic function. Expression of UAS-Hiw late in PD (C42.2 driver) rescued axon morphology, but not synaptic function. Presynaptic expression of a Hiw missing its RING domain with the R91H05 driver failed to rescue morphology or synaptic function, showing that the ligase activity of Hiw is required. PD, pupal development; RING, really interesting new gene; WT, wild-type.

We also attempted to rescue hiwND8 mutants by expressing a truncated Hiw allele that is missing the RING domain (hiwND8/>; UAS-hiwΔRING/+; R91H05/+). This hiw allele failed to rescue either the anatomical (0% WT) or the physiological (4.17% WT) hiwND8 phenotype (n = 14 and P = 0.0168) (Figure 4). Thus, the ubiquitin ligase activity of Hiw is required presynaptically for proper synapse assembly. Overexpression of Hiw in the GFS (A307-Gal4/UAS-Hiw, 100% WT anatomy, and n = 18; 87.5% WT physiology and n = 14) in a WT background had no effect on the GF:TTMn synapse (data not shown).

The role of Hiw in regulating synaptic structure and function can also be separated temporally. In hiwND8 mutants, expression of Hiw in the GF after 50% of PD, which is after the time the giant synapse has formed (hiwND8/>; UAS-Hiw/+; C42.2/+), significantly rescued anatomical defects (73.68% WT, P = 0.0011) but did not rescue synaptic function (0% WT and P = 0.1162) (Figure 4). Axon anatomy apparently remained plastic late in development, whereas the window for proper synapse function was limited. If Hiw is restored after the time of synapse formation, the anatomical defect can be corrected, presumably by pruning, while the earlier functional damage is permanent.

Hiw negatively regulates the MAPK pathway in the GFs to promote axon pruning

Because the ubiquitin ligase activity of Hiw was required for normal GFS development, we examined a known ubiquitination target of Hiw, Wnd. The hiw anatomical phenotype was suppressed by removing one copy of wnd (hiwND8/>; wnd1/+) (n = 10, P = < 0.0001) (Figure 5I); anatomical phenotypes shift from 30.56% WT in hiwND8 mutants to 100% WT upon genetic suppression. Because overexpression of Wnd results in overgrown synapses at the fly NMJ (Collins et al. 2006), we attempted to overexpress Wnd in the GFS. However, overexpression of Wnd in the GFs (A307/UAS-Wnd) caused lethality in late larval/pupal stages. Using the presynaptic driver R91H05 (UAS-Wnd/+; R91H05/+), we were largely unable to locate GFs, and only observed three out of a potential 40 GFs. The three GFs that were dye-injected did resemble the hiwND8 phenotype (data not shown). Loss-of-function (LOF) wnd mutants are also late larval/pupal lethal, indicating that the development in late larval and pupal stages is very sensitive to Wnd levels.

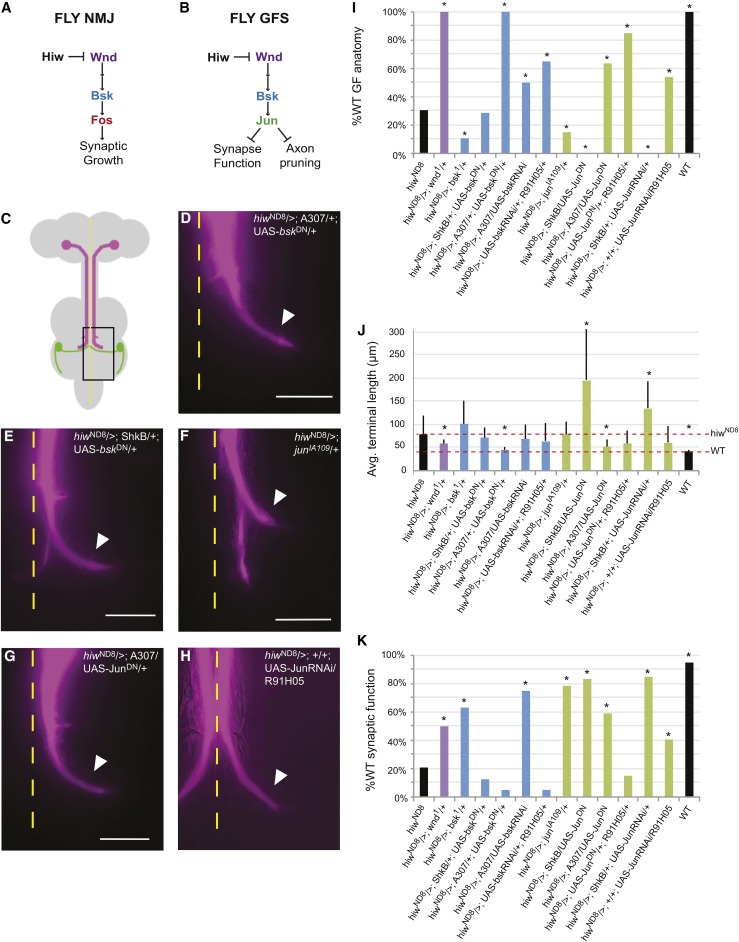

Figure 5.

Knocking down the MAPK pathway rescued the hiwND8 phenotype. (A) The MAPK pathway as proposed for the fly NMJ. (B) The MAPK pathway proposed for the fly GFS. (C) Cartoon representation of the fly CNS. Box denotes area shown in micrographs. (D–H) Fluorescence Extended Depth of Focus images of GF axon terminals filled with Lucifer yellow (recolored magenta). ImageJ Background Subtraction was used. Calibration bar = 20 µm. Arrowhead marks normal terminal bend. The hiw mutant phenotype was rescued by the strong presynaptic knockdown of Bsk in hiwND8/>; A307/+; UAS-bskDN/+ (see D). Postsynaptic expression of the basket dominant negative hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-bskDN/+ mutants exhibits the caudal branch, showing the absence of a postsynaptic role for Bsk (see E). Mutant anatomy was not rescued by a heterozygous version of jun in a hiw background (hiwND8/>; junIA109/+) (see F). hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-JunDN provided a strong knockdown of Jun and rescued anatomy (see G). Expression of JunRNAi in the GFs hiwND8/>; +/+; UAS-JunRNAi/R91H05 also rescued anatomy (see H). (I) % WT GF anatomy, * P = ≤ 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test vs. hiwND8). (J) Average terminal lengths (micrometer), * P ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t-test vs. hiwND8). (K) % WT GF physiology, * P ≤ 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test vs. hiwND8). Avg., average; GF, giant fiber; GFS, GF system; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; RNAi, RNA interference; WT, wild-type.

In the canonical pathway (Figure 5A), Wnd acts upstream of Bsk. Therefore, we expected bsk mutants to suppress hiwND8 and proceeded to knock down Bsk in the hiwND8 males. Heterozygous bsk1 in a hiwND8 background (hiwND8/>; bsk1/+) did not suppress the anatomical phenotype (n = 28, 10.7% WT, and P = 0.0431), and the average terminal length, 101.0 µm, was not significantly different from hiwND8 mutants (P = 0.1533) (Figure 5, I and J). To obtain a stronger knockdown of Bsk, we expressed bsk RNAi in the GFs. Expression of bsk RNAi by the pre-/postsynaptic A307 driver (hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-bsk RNAi) trended toward suppression with an increase to 50% WT GF anatomy, (n = 20 and P = 0.1193) (Figure 5I) and the average terminal length was 68.38 µm (P = 0.3622) (Figure 5J), changes that were not significantly different from hiwND8. The bskDN construct has been found to provide a stronger knockdown than bsk RNAi (Lesch et al. 2010). Therefore, we expressed bskDN (hiwND8/>; A307/+; UAS-bskDN/+) pre- and postsynaptically, which resulted in 100% anatomically WT GFs (n = 13 and P = < 0.0001) and decreased the average terminal length to 44.69 µm (P = 0.0008) (Figure 5, D, I, and J). We also expressed bskDN in the postsynaptic TTMn (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-bskDN/+) but observed no significant suppression, with 28.6% WT (n = 21 and P > 0.9999) and an average terminal length of 71.41 µm (P = 0.4957) (Figure 5, E, I, and J). This suggests that the suppression is due to presynaptic expression, not due to any postsynaptic expression. We confirmed that a stronger knockdown can rescue hiwND8 morphology by driving bsk RNAi with the stronger presynaptic promoter R91H05 (hiwND8/>; UAS-bsk RNAi/+; R91H05/+), which significantly suppressed the anatomical defect to 65% WT (n = 20 and P = 0.0187). The average terminal length was reduced to 63.03 µm, though this was not significant, likely to due to averaging over an incomplete suppression (P = 0.22). These experiments confirmed the cell-autonomous role for Bsk and its regulation by Hiw.

Because output of the MAPK cascade works through Fos at the NMJ (Figure 5A), and Fos can bind Jun to function as the AP-1 transcription factor, we tested these two transcription factors in the GFS. To our surprise, we found that Jun, not Fos, was the functioning factor in GFS development (Figure 5B). In this section, we describe the role of Jun and in the next section describe a new role for Fos.

Heterozygous Jun (hiwND8/>; junIA109/+) had relatively weak effects and did not suppress GF anatomy, with only 15% WT (n = 20 and P = 0.256) and no significant difference in average terminal length when compared to hiwND8 mutants (77.8 µm, P = 0.9441) (Figure 5, F, I, and J). However, strong pre- and postsynaptic expression of JunDN (hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-JunDN) significantly suppressed GF anatomy (n = 22, 63.6% WT, and P = 0.011) (Figure 5, G and I). The average terminal length was 52.02 µm (P = 0.0073), significantly shorter than hiwND8 mutants (Figure 5J). (Figure 5J). Similarly, expressing JunDN under the strong presynaptic promoter R91H05 (hiwND8/>; UAS-JunDN/+; R91H05/+) also significantly suppressed to 85% WT (n = 20 and P = < 0.0001). Thus, a strong knockdown of Jun is required to suppress the hiwND8 anatomical defects. Postsynaptic expression of JunDN (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-JunDN/+) exaggerated the hiwND8 phenotype, with 0% WT (P = 0.0048) and an increased average terminal length of 194.24 µm (P = < 0.0001) (Figure 5, I and J). JunDN and FosDN, both constructs widely used in the fly community, are capable of binding to their native partners, including formation of homo- and heterodimers (AP-1), though they cannot effectively recruit the transcription complex (Eresh et al. 1997). Therefore, the increased terminal length observed when expressing JunDN postsynaptically could be the result of either a postsynaptic role for Jun or an artifact of JunDN binding to, and by proxy, knocking down Fos function or access to transcription sites. To avoid these problems, we tested RNAi knockdown of Jun using separate pre- and postsynaptic drivers.

Presynaptic expression of JunRNAi using the presynaptic driver R91H05 (hiwND8/>; +/+; R91H05/UAS-Jun RNAi) significantly suppressed GF anatomy to 54.05% WT (n = 37 and P = 0.0403) (Figure 5I). The average length of GF terminals was not significantly rescued because the rescue was partial (58.94 µm and P = 0.0659) (Figure 5J). Interestingly, postsynaptic expression of JunRNAi (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-JunRNAi/+) also showed an exaggerated phenotype, with no WT terminals (n = 25 and P = 0.0003) and a significantly increased average terminal length of 133.61 µm (P = 0.0006). This suggests that, in addition to working presynaptically to suppress pruning, Jun also has a postsynaptic role restraining presynaptic axon growth, similar to Fos (see below).

Mutants in the MAPK pathway suppress hiw mutant synaptic function

Because we have shown that structure and function are regulated independently, we present the data for synaptic function in this separate section. The physiological defects of the hiwND8 allele were suppressed by knocking down genes in the MAPK pathway (Figure 5K). Heterozygous wnd1 (hiwND8/>; wnd1/+) significantly suppressed the hiw phenotype (n = 20, 50% WT, and P = 0.0204) (Figure 5K). Though a partial suppression, each electrophysiological parameter we used to determine WT status was significantly improved from hiwND8 mutants. Average TTM latency improves from 1.29 msec in hiwND8 mutants to 1.03 msec (P = 0.0069). The following frequency at 100 Hz improves from 51.6 to 80.75% (P = 0.0016) and at 200 Hz from 38.95 to 67.45% (P = 0.0011). To determine if the glial suppression of hiwND8 is acting through the negative regulation of Wnd, we overexpressed Wnd in the midline glia. Unfortunately, overexpression of Wnd in the midline glia (UAS-Wnd/+; Slit/+) resulted in late larval/pupal lethality. Consequently, we cannot determine if Hiw’s non-cell autonomous role in synaptic function is dependent upon Wnd.

The knockdown by bsk1 heterozygotes and expression of bsk RNAi suppressed synaptic function defects (Figure 5K). Heterozygous bsk1 (hiwND8/>; bsk1/+) significantly suppressed hiwND8 males physiologically, from 20.83 to 65% WT (n = 39 and P < 0.0001). Pre- and postsynaptic expression of bsk RNAi (hiwND8/>; A307/ UAS-bsk RNAi) suppressed physiology defects to 95% WT (n = 20 and P = < 0.0001). However, the stronger knockdown by bskDN expression (hiwND8/>; A307/+; UAS-bskDN/+) proved too strong for proper function, as only 5% of GFs were WT (n = 20 and P = 0.1822) (Figure 5K). Similarly, strong expression of bsk RNAi (hiwND8/>; UAS-bsk RNAi/+; R91H05/+) also failed to suppress synaptic function defects, with only 5% WT (n = 20, P = 0.1822). We interpreted this to mean that there is a lower threshold for Bsk that is necessary for proper synaptic function. Indeed, A307-driven expression of bskDN in a WT background was extremely toxic to function as the circuit was functionally disconnected, even though the axon terminals looked WT (data not shown). Postsynaptic expression of bskDN (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-bskDN/+) had no effect on synaptic function (n = 24, 12.5% WT, and P = 0.5475) just as it had no effect on anatomy, thus reinforcing that Bsk functions cell-autonomously, downstream of Hiw, within the presynaptic GF.

Knocking down Jun also suppressed synaptic function defects. Heterozygous junIA109 (hiwND8/>; junIA109/+) significantly suppressed synaptic function (n = 14; 78.6% WT, and P = < 0.0001) (Figure 5K). Synaptic function is sensitive to levels of Jun, similar to Bsk, where too high or too low levels are detrimental. We still see suppression when we expressed JunRNAi presynaptically (hiwND8/>; +/+; R91H05/UAS-JunRNAi), with 40.63% WT (n = 37 and P = 0.0305), though this is clearly a partial suppression. Expression of JunDN with the strong presynaptic driver (hiwND8/>; UAS-JunDN/+; R91H05/+) failed to suppress synaptic function, with 15% WT (n = 20 and P = 0.7557) because Jun levels are too low to support proper synaptic function. Expressing JunDN with the pre- and postsynaptic driver A307, which expresses less strongly in the GFs than R91H05, suppressed to 59.09% WT (n = 22 and P = 0.001), reflecting how variation in Jun levels affects synaptic function. Postsynaptic expression of JunRNAi (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-JunRNAi/+) significantly suppressed synaptic function (n = 25 and P = < 0.0001), along with JunDN (hiwND8/>; ShkB/UAS-JunDN), which rescued to 83.33% (n = 18 and P = < 0.0001). This suggests that, in addition to Jun’s postsynaptic role in restraining presynaptic axon growth, it also promotes proper synap-tic function.

Fos expression non-cell autonomously promotes axon growth

Because Fos acts at the larval NMJ, we suspected that Fos may be acting downstream of Bsk in the GFS. If this were true, knocking down Fos in hiwND8 males would suppress hiwND8 phenotypes in a manner similar to the Jun LOF. Contrary to this hypothesis, heterozygous fosEY12710 (hiwND8/>; fosEY12710/+) enhanced the hiwND8 phenotype anatomically, with 0% WT (n = 20 and P = <0.0001) (Figure 6, A and F) and a significantly increased average terminal length to 133.65 µm (P = 0.0003) (Figure 6H). This suggested that Fos was not acting downstream of the MAPK pathway in the GFs.

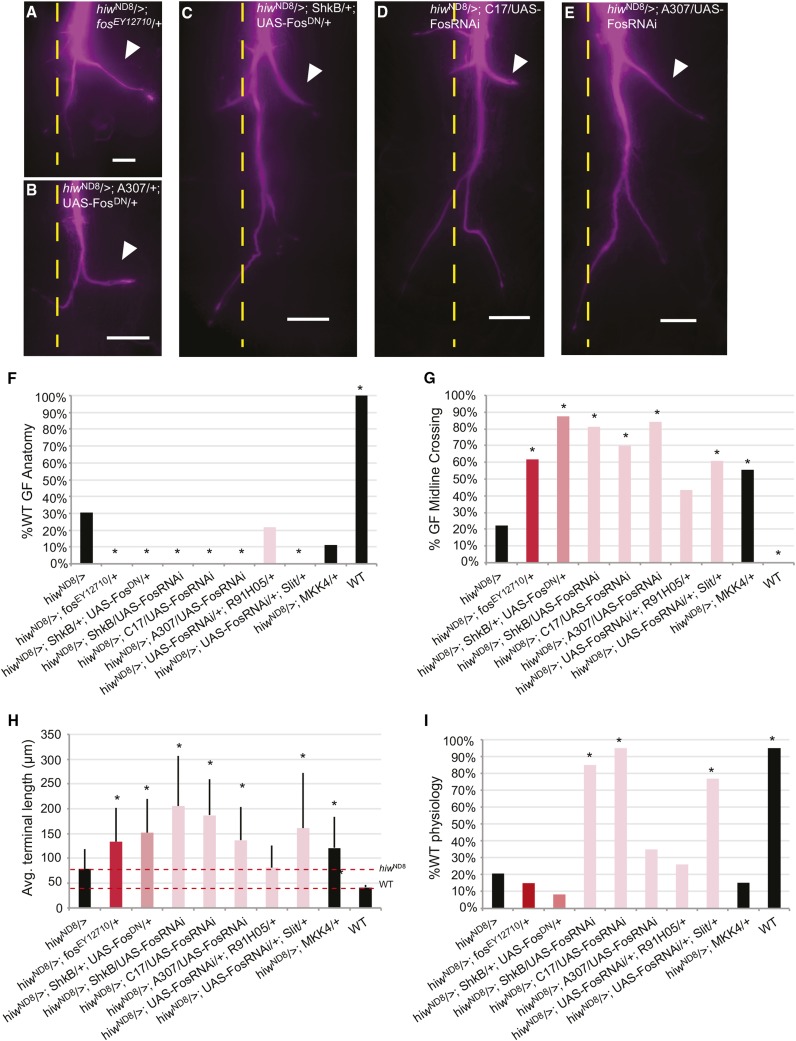

Figure 6.

Knockdown of Fos in a hiwND8 background disrupts pruning. (A–E) Single GF axon terminals were filled with Lucifer yellow (recolored magenta) and images shown as Extended Depth of Focus compressed stacks. (A) hiwND8/>; fosEY12710/+ has increased terminal length compared to hiwND8. (B) hiwND8/>; A307/+; UAS-FosDN/+ axon terminal lengths were not significantly longer than hiwND8. Disruption of Fos in TTMn and midline glia significantly increased axon terminal lengths: (C) hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-FosDN/+, (D) hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-FosRNAi, and (E) hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-FosRNAi. Calibration bar = 20 µm. The GF terminal bend along the TTMn dendrite is marked by an arrowhead. (F) Percent anatomically WT GFs observed in various genotypes. Knocking down Fos non-cell autonomously in glia or TTMn enhanced GF anatomical defects. * P < 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test). (G) Percent GFS crossing the midline observed in various genotypes. Knocking down Fos strongly in the midline glia and TTMn increased midline crossing. * P < 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test). (H) Average terminal lengths (micrometer) observed in various genotypes. * P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). (I) Percent of GFs with WT synaptic function observed in various genotypes. Knocking down Fos strongly in the midline glia and TTMn rescued synaptic function. All mutants were compared to hiwND8. * P < 0.05 (Fisher’s exact test). Avg., average; GF, giant fiber; GFS, GF system; TTMn, tergotrochanteral jump muscle neuron; RNAi, RNA interference; WT, wild-type.

To more carefully examine the effects of Fos in the GFS, the FosDN allele and FosRNAi were expressed separately in the various components of the GFS. Exclusively presynaptic expression of FosRNAi (hiwND8/>; UAS-FosRNAi/+; R91H05/+) failed to alter the hiw phenotype with 21.74% WT (n = 23 and P = 0.436) and an average terminal length of 81.32 µm (P = 0.436). This suggests that Fos is not acting downstream of Hiw to suppress pruning in the GF. In contrast, strong postsynaptic knockdown of Fos phenocopied the fos heterozygotes (hiwND8/>; fosEY12710/+). Postsynaptic FosRNAi expression (hiwND8/>; ShkB/UAS-FosRNAi) enhanced the hiwND8 anatomical phenotype, with 0% WT (n = 16 and P = 0.009) and an average terminal length of 205.59 µm (P = 0.0002) (Figure 6, F and H). These result show that Fos acts in the postsynaptic TTMn to restrain presynaptic axon growth of the GF. The dominant negative (DN) construct (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-FosDN/+) had a similar effect and enhanced the defect (0% WT, n = 16, and P = 0.009), increasing average terminal length to 151.83 µm (P = 0.00036) (Figure 6, C, F, and H) with the caveat that there may be confounding effects of the DN construct mentioned above.

Finally, we knocked down expression in the midline glia. FosRNAi was expressed with Slit-GAL4 (hiwND8/>; UAS-FosRNAi/+; Slit/+). This resulted in axon overgrowth with average terminal length of 161.06 µm (P = 0.0036) and 0% WT GFs (P = 0.0013) (Figure 6, F and H). Again, we confirmed the effect with another driver known to express in midline glia. Expressing FosRNAi under the C17 driver (hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-FosRNAi), which is known to express in midline glia (Orr et al. 2014), we observed even more severe axon overgrowth with an average terminal length significantly increased to 187.47 µm (P = < 0.0001) (Figure 6, D, F, and H) and a dramatic increase in penetrance (0% WT, n = 20, and P = 0.0025).

In addition to the non-cell autonomous effect on axon terminal length, Fos also affects the ability of the GF to cross the midline. In hiwND8 mutants, 22.22% of axons crossed the midline (Figure 6G). When one copy of fos (hiwND8/>; fosEY12710/+) was disrupted, there was a significant increase in midline crossing (61.76% and P = 0.0002). Expressing FosRNAi in midline glia (hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-FosRNAi) significantly increased midline crossing as well (hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-FosRNAi, 70%, and P = 0.0002; hiwND8/>; UAS-FosRNAi/+; Slit/+, 60.87% cross, and P = 0.0014). Exclusive presynaptic expression (hiwND8/>; UAS-FosRNAi/+; R91H05/+) had no significant effect on midline crossing (43.48% and P = 0.0621). Strong pre- and postsynaptic expression (hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-FosRNAi) resulted in 84.21% crossing (P = < 0.0001) and exclusive postsynaptic expression (hiwND8/>; ShkB/UAS-FosRNAi) resulted in 81.25% crossing (P = < 0.0001), confirming that Fos acts in a non-cell autonomous fashion.

Knockdown of the MAPK kinase MKK4, which works in parallel to the MAPK kinase MKK7 that phosphorylates Bsk, in hiwND8 males (hiwND8/>; MKK4/+) phenocopied the heterozygous knockdown of fos in hiwND8 males (Figure 6, F, G, and H) (11.1% WT, n = 18, and P = 0.1373). As with the fos LOF mutant, GFs exhibited enhanced axon overgrowth, with an average terminal length of 121.39 µm (n = 17 and P = 0.0214 vs. hiwND8). This data suggests that Fos and Jun could be activated by the MKK4/p38 pathway in the TTMn and glia, while Jun is activated by Bsk in the GFs. Targeted knockdowns of MKK4 would be useful to confirm this relationship.

Fos knockdown non-cell autonomously suppresses synaptic function in the GFS

All of the suppression effects of Fos on physiology emanated from outside the GF (Figure 6). Postsynaptic expression of FosRNAi (hiwND8/>; ShkB/UAS-FosRNAi) suppressed synaptic function (n = 22, 85% WT, and P = < 0.0001). Although postsynaptic expression of FosDN (hiwND8/>; ShkB/+; UAS-FosDN/+) did not suppress the physiology defect (n = 24, 8.33% WT, and P = 0.2241), the lack of functional rescue when expressing FosDN may be the result of the DN construct or suggest possible dosage effects. Knocking down Fos in midline glia also suppressed synaptic function (hiwND8/>; UAS-FosRNAi/+; Slit/+) to 76.92% WT (n = 26 and P < 0.0001). Expressing FosRNAi with the C17 driver, known to express in glia, also suppressed the physiology with 95% WT (n = 20 and P = < 0.0001) (hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-FosRNAi) (Figure 6I).

In contrast, presynaptic knockdown of Fos with FosRNAi (hiwND8/>; UAS-FosRNAi/+; R91H05/+) failed to suppress the physiology defects with 26.09% WT (P = 0.547). Heterozygous Fos LOF (hiwND8/>; fosEY12710/+) was also unable to suppress function (n = 20, 15% WT, and P = 0.7535) (Figure 6I), reinforcing that Fos is not acting downstream of Hiw in the GFs and that a strong non-cell autonomous knockdown of Fos is required to suppress synaptic function in hiwND8 mutants. We suspect that the dosage requirements of Fos for morphology and function are different.

Knockdown of MKK4 in hiwND8 males (hiwND8/>; MKK4/+) also failed to suppress synaptic function defects (Figure 6I) (15% WT, n = 20, and P = 0.1789) in addition to anatomical defects. These phenotypes are similar to heterozygous loss of Fos, again suggesting that MKK4 may act upstream of Fos and Jun in the midline glia or TTMn.

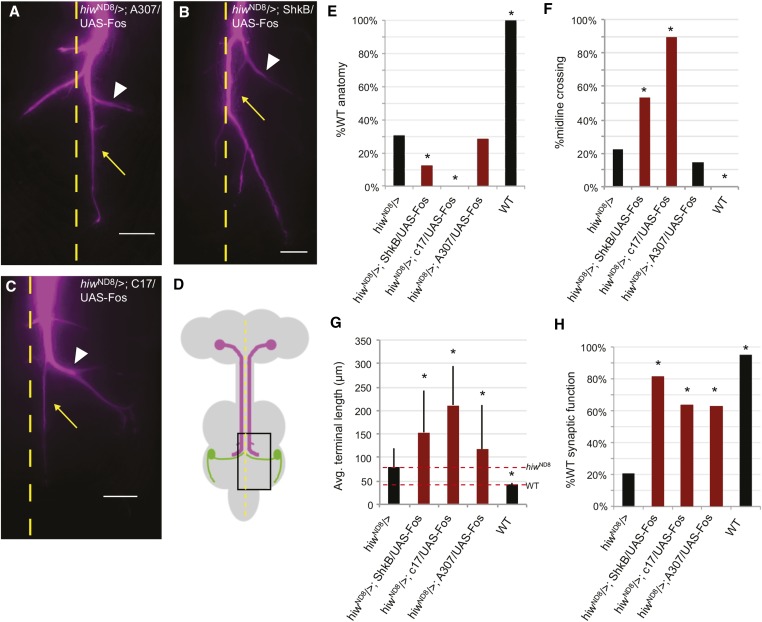

Fos overexpression affects GFs similarly to Fos knockdown

Surprisingly, overexpression of WT Fos in hiwND8 males produced similar phenotypes to Fos knockdown; in both scenarios, axon overgrowth and improvement in synaptic function was observed (Figure 7). Postsynaptic overexpression (hiwND8/>; shkB/UAS-Fos) resulted in 12.5% anatomically WT GFs (P = 0.2161), with an average length of 152.48 µm (n = 16 and P = 0.0079) (Figure 7, B, E, and G). Physiologically, 81.25% of GFs were WT (n = 16 and P = < 0.0001) (Figure 7H). Fos overexpression in midline glia (hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-Fos) resulted in 0% anatomically WT GFs (n = 19 and P = 0.0049), with an average length of 210.19 µm (P = < 0.0001) (Figure 7, C, E, and G). Physiologically, 63.6% of GFs were WT (n = 22 and P = 0.0004) (Figure 7H). Pre- and postsynaptic expression (hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-Fos) resulted in 28.57% anatomically WT GFs (n = 7 and P > 0.9999), with an average length of 117.78 µm (n = 7 and P = 0.3204) (Figure 7, A, E, and G). Physiologically, 62.5% of GFs were WT (n = 8 and P = 0.0208) (Figure 7H). A similar trend continued for midline crossing phenotypes. Postsynaptic overexpression increased midline crossing from 22.22 to 73.33% (P = 0.0003) (Figure 7F). Overexpression in the midline glia increased midline crossing to 89.47% (P = < 0.0001). Pre- and postsynaptic expression of Fos did not result in a significant change in midline crossing in hiwND8 mutants with 14.29% crossing (P = 1.0). We think that the effect of postsynaptic overexpression by the A307 driver was concealed by the strong presynaptic ectopic expression of Fos.

Figure 7.

Fos overexpression in a hiwND8 background. Extended Depth of Focus compressed stacks of Lucifer yellow-filled GF terminals (recolored magenta). Calibration bar = 20 µm. Overexpression of Fos in a hiwND8 background rescued synaptic function and increased axon growth: (A) hiwND8/>; A307/UAS-Fos, (B) hiwND8/>; ShkB/UAS-Fos, (C) hiwND8/>; C17/UAS-Fos, and (D) Schematic of the CNS. Boxed area shows giant synapse region shown in A–C. (E) Percent WT GF anatomy observed in different genotypes. (F) Percent GFs that cross the midline observed in different genotypes. (G) Average terminal lengths (micrometer) observed in different genotypes. (H) Percent WT GF physiology observed in different genotypes. Mutants were compared to hiwND8. * P < 0.05; (E–G) used the Fisher’s exact test. (H) used a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Avg., average; GF, giant fiber; WT, wild-type.

Hiw regulates GF axon termination

It is important to note that manipulating Fos in a WT background did not yield axon overgrowth. Heterozygous fosEY12710 without the hiwND8 male background or expressing either FosRNAi or the FosDN allele resulted in generally anatomically WT axon terminals. We observed similar results when overexpressing WT Fos in a WT background. This suggests that the non-cell autonomous effect of Fos manipulation is reliant on the absence of Hiw. Therefore, we suggest that Hiw promotes axon termination and pruning in the CNS. Similarly, manipulating Fos in a WT background overwhelmingly had no effect on synaptic function. Heterozygous fos showed mild deleterious effects with 72.73% WT (P = 0.046 vs. Urbana-S), namely a decreased ability to follow high-frequency stimulation. Additionally, manipulating Fos in a heterozygous hiwND8 background generally did not affect axon growth or synaptic function; one copy of hiw was sufficient for function (data not shown).

Discussion

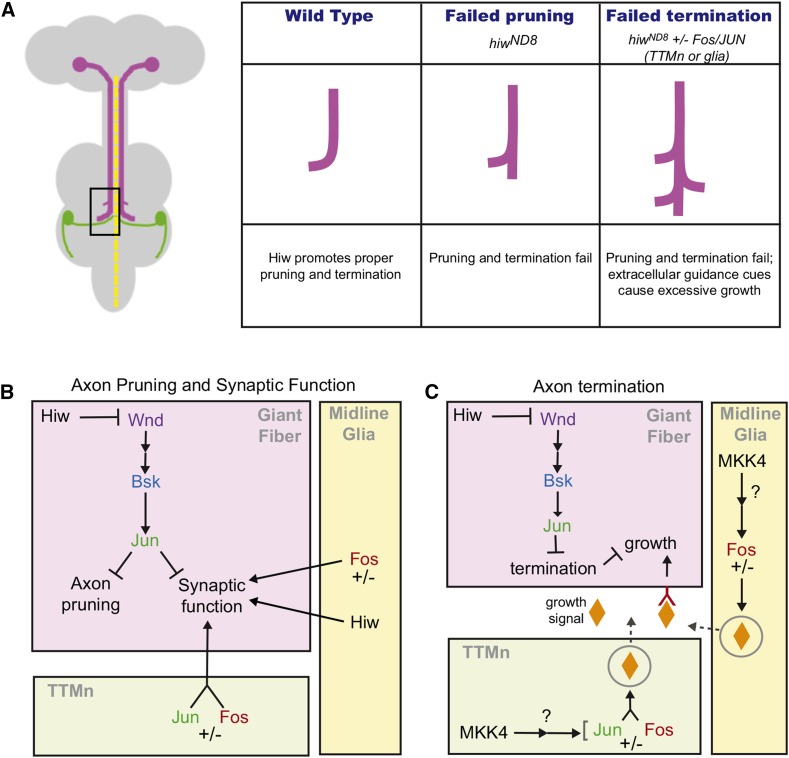

Hiw coordinates many aspects of the assembly of synaptic circuits including axon pruning, axon termination, and synaptic function (Figure 8). We have revealed a number of similarities and differences between Hiw function at the central synapse of the fly GFS and the peripheral synapse of the fly NMJ. At both the central and peripheral synapse, Hiw functions cell-autonomously in the presynaptic cell to regulate structure through negative regulation of a MAPK pathway. However, there are distinctions between the two synapses. At the central synapse, the output of the MAPK pathway is Jun while at the NMJ it is Fos. Further, synaptic function is regulated by Hiw at the two synapses but the regulatory machinery seems to be quite different. While the MAPK pathway regulates both structure and function at the central synapse, there appears to be a separate pathway for function at the NMJ. Finally, there are a number of non-cell autonomous regulatory affects at the central synapse that have not been seen at the peripheral NMJ. In particular, Hiw has a strong regulatory effect on synaptic function mediated by glia.

Figure 8.

Model of Hiw and MAPK activity in the GFS. (A) color coded schematic of the CNS with various giant fiber phenotypes schematized. (B) Hiw acts in the GFs to negatively regulate pruning and function via the Wnd MAPK cascade, which includes Bsk and Jun. The MAPK cascade suppresses both synaptic function and axon pruning. Names of proteins are displayed in the colors that were used in Figure 5 and Figure 6: Wnd (purple), Bsk (blue), Jun (green), and Fos (red). Hiw also acts in the glia to promote synaptic function. (C) Hiw also acts in the GFs to regulate axon termination, likely by regulating a receptor that binds a secreted growth signal(s) (orange diamond), which comes from the TTMn and/or glia; this trans-synaptic signal is controlled by Fos. Because mkk4 LOF phenocopies fos LOF in the hiwND8 background, we suspect Mkk4 may act upstream of Fos as part of a parallel MAPK canonical positive regulation pathway. GF, giant fiber; GFS, GF system; LOF, loss-of-function; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; TTMn, tergotrochanteral jump muscle neuron.

Role of Hiw in synaptic function

In the GFS, Hiw cell-autonomously promotes synaptic function by negatively regulating the Wnd MAPK cascade, and expressing Hiw presynaptically in hiwND8 mutants rescued the physiological defects (Figure 8B). This parallels the role of Hiw at the NMJ, where it is also required presynaptically and, when expressed in the motor neuron, can rescue the functional defects (Wu et al. 2005). Expression of hiw∆RING was unable to rescue defects at the NMJ (Wu et al. 2005) or GFS, reinforcing the primary role of Hiw in negative regulation of Wnd in regulating synaptic structure and function. The nature of the synaptic function defects in the GFS remains uncertain. Gap junctions, the predominant force at the giant synapse, are intact but their exact strength is unclear. hiw mutant terminals were often thinner than normal, and impedance mismatching may explain some of the synaptic defects.

Knocking down Wnd, Bsk, or Jun suppressed the GFS physiological hiw defects, showing that function was regulated through the MAPK cascade (Figure 8B). This is distinct from the NMJ, where attenuating expression of Wnd has no effect on synaptic function in hiw mutants (Collins et al. 2006). Using classical alleles, RNAi, and DN constructs, we showed in the GFS that there were distinct MAPK dosage requirements for proper synaptic function. If the levels of MAPK activity were too high or too low, synaptic function was disrupted. However, for proper axon morphology, it was only important that MAPK levels did not go too high, showing distinct activity thresholds for structure and function. Upper and lower thresholds for MAPK dosage have been described previously in both the fly (Rallis et al. 2010) and worm (Nakata et al. 2005).

We also revealed a non-cell autonomous role for Hiw wherein Hiw functions in the midline glia to promote synaptic function (Figure 8B). Hiw has been shown to act non-cell autonomously in axon guidance in the Drosophila mushroom body (Shin and DiAntonio 2011), but the GFS is the first example of Hiw working non-cell autonomously to influence synaptic function. We also observed a non-cell autonomous effect on synaptic function when manipulating Fos expression. The manipulation of Fos expression in TTMn and glia in hiw mutants caused GF synaptic function to improve. Even though there was no Hiw in these mutant GFs, the trans-synaptic signal was able to counter the deleterious physiological effects of too much MAPK activity.

The role of Hiw in synapse structure

hiw mutants in both the NMJ and GFS show increases in axon terminal lengths, although the mechanisms underlying these phenotypes differ. In the GFS, Hiw promotes axon pruning cell-autonomously by negatively regulating the Wnd MAPK cascade (Figure 8, A and B) and the loss of pruning leads to the increased axon terminal length. Knocking down components of the MAPK pathway, including Wnd, Bsk, and the transcription factor Jun, suppressed the pruning defects in hiw mutants. This is in contrast to the larval NMJ, where Hiw appears to function by restraining excessive growth via negative regulation of Wnd. Development of the larval NMJ is marked by increased synaptic branching and bouton number as the animal and its muscle fibers grow throughout development and loss of Hiw leads to excess growth (Atwood et al. 1993; Schuster et al. 1996; Menon et al. 2013). This suggests that Hiw acts at the NMJ to regulate axon termination, a role that is conserved, for example, in worms (Grill et al. 2016).

Pruning and degeneration are regulated by a number of overlapping molecular pathways. The ubiquitin–proteosome system has been implicated in developmental pruning (Watts et al. 2003; Zhai et al. 2003; Kuo et al. 2006) and pruning in the fly has been described as Wallerian degeneration-like (Hoopfer et al. 2006). Hiw is known to regulate axon injury response through regulations of Wnd and NMNAT (Xiong et al. 2010, 2012). Hiw promotes degeneration in response to injury by ubiquitinating the neuroprotective protein NMNAT in the distal axon (Xiong et al. 2010, 2012) and blocks degeneration in the proximal axon by ubiquitinating Wnd (Xiong et al. 2012; Babetto et al. 2013). Wnd/DLK and Bsk/JNK have been shown to promote neuronal degeneration in response to injury across several studies and models (Miller et al. 2009; Ghosh et al. 2011; Babetto et al. 2013). In the mushroom body, Bsk/JNK is specifically necessary for axon, but not dendrite, pruning in development (Bornstein et al. 2015). Conversely, Bsk/JNK has a protective role against age-related degeneration in the fly mushroom body (Rallis et al. 2013). Interestingly, our results also show a more protective role for the MAPK pathway, including Wnd and Bsk, which acts to block pruning in development. These results show that core machinery (Hiw and the MAPK pathway) is regulated in specific ways to achieve similar but distinct cellular processes.

The role of Hiw/RPM-1 in axon termination has been well-documented (Grill et al. 2016). In hiw mutants, we occasionally observe GFs with extremely long caudal branches or tertiary branching (Figure 3, N and O). This excessive axon growth of GFs suggests that axon termination is disrupted, in addition to defects in pruning. Manipulation of Fos expression highlighted this termination defect. Altering expression of Fos in the postsynaptic TTMn or the midline glia in hiw mutants resulted in excessive axon growth of the GFs, with significantly longer axon terminals compared to hiw alone. Apparently Fos in glia or TTMn regulates an unidentified trans-synaptic cue that causes the GFs to continue growing. When Hiw was present in the GFs, manipulating Fos expression in the TTMn or glia had no effect on GFs. This suggests that Hiw promotes axon termination by suppressing the ability of the GFs to respond to external cues coming from the TTMn and glia, perhaps by regulating guidance receptors (Figure 8C).

Another example of Hiw regulating recognition of external cues was illustrated by the fact that manipulating Fos expression in hiw mutants also caused almost all of the GFs to ignore the midline barrier and cross to the contralateral side. We speculate that Fos may impact Slit-Robo signaling and that Hiw regulates Robo in the GFs. Removal of Robo inhibition by Hiw and adjusting the non-cell autonomous signal (seemingly Slit), the GFs are free to ignore the midline and cross, resulting in roughly 80% of GFs crossing the midline. Bolstering this idea, previous work in the worm has shown that RPM-1 regulates trafficking of Robo (Li et al. 2008).

Both overexpression and knockdown of Fos in hiw mutants had similar effects. While this was initially unexpected, MKK4 has been shown to have similar bipolar effects in C. elegans (Nakata et al. 2005). Indeed, heterozygous MKK4 showed a relationship to Hiw similar to that between Hiw and Fos. This suggests that MKK4 and Fos may function in the same pathway in the TTMn or glia to influence axon growth when termination fails.

In other systems, Fos often functions with Jun as the heterodimeric AP-1 transcription factor, which is activated by Bsk (Bohmann et al. 1994; Eresh et al. 1997; Sanyal et al. 2002, 2003). Here, we show that AP-1 is not acting presynaptically at the central synapse of the GFS, because Jun acts in the GFs to suppress pruning while Fos does not. This is parallel to the NMJ result where Fos acts in the motor neurons but Jun does not. Though we observe a postsynaptic effect for Jun similar to Fos, it appears that the trans-synaptic cues are not dependent on AP-1 function, as overexpression of Fos elicited excessive axon growth without the coexpression of Jun.

Finally, experiments examining Fos and Jun presented here highlight limitations of commonly used genetic tools in the fly community. Because we were able to separate cell-autonomous vs. noncell-autonomous contributions in the GFS, we were able to observe the differential effects of the FosDN and JunDN constructs vs. RNAi. For example, because Fos and Jun have different functions pre- vs. postsynaptically in the GFS, simultaneously expressing FosDN pre- and postsynaptically appears to sequester Jun in the GFs and effectively masks the trans-synaptic effect on axon termination (data not shown), whereas expression of FosRNAi had no effect presynaptically and showed the trans-synaptic effect on termination. The differences between them appear to be an artifact of the DN constructs potentially sequestering binding partners. Therefore, future experiments using the FosDN and JunDN constructs must be interpreted carefully and are well-complemented by using RNAi.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Jupiter Life Science Initiative funds from the FAU Provost's Office as well as the Romer Foundation-Florida Atlantic University Center for Rare and Neurological Diseases (grant no. R71941). This material is also based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant no. DGE: 0638662. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The authors would like to thank Diane Baronas-Lowell for her copyediting help.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: H. J. Bellen

Literature Cited

- Abrams B., Grill B., Huang X., Jin Y., 2008. Cellular and molecular determinants targeting the Caenorhabditis elegans PHR protein RPM-1 to perisynaptic regions. Dev. Dyn. 237: 630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. J., Godenschwege T. A., 2010. Electrophysiological recordings from the Drosophila giant fiber system (GFS). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010: pdb prot5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. J., Drummond J. A., Moffat K. G., 1998. Development of the giant fiber neuron of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Comp. Neurol. 397: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood H. L., Govind C. K., Wu C. F., 1993. Differential ultrastructure of synaptic terminals on ventral longitudinal abdominal muscles in Drosophila larvae. J. Neurobiol. 24: 1008–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin H., Allen M. J., Partridge L., 2011. Electrophysiological recordings from the giant fiber pathway of D. melanogaster. J. Vis. Exp. 47: 2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babetto E., Beirowski B., Russler E. V., Milbrandt J., DiAntonio A., 2013. The Phr1 ubiquitin ligase promotes injury-induced axon self-destruction. Cell Rep. 3: 1422–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen H. J., Levis R. W., Liao G., He Y., Carlson J. W., et al. , 2004. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics 167: 761–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom A. J., Miller B. R., Sanes J. R., DiAntonio A., 2007. The requirement for Phr1 in CNS axon tract formation reveals the corticostriatal boundary as a choice point for cortical axons. Genes Dev. 21: 2593–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner J., Godenschwege T. A., 2011. Whole mount preparation of the adult Drosophila ventral nerve cord for giant fiber dye injection. J. Vis. Exp. 52: 3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohmann D., Ellis M. C., Staszewski L. M., Mlodzik M., 1994. Drosophila Jun mediates Ras-dependent photoreceptor determination. Cell 78: 973–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein B., Zahavi E. E., Gelley S., Zoosman M., Yaniv S. P., et al. , 2015. Developmental axon pruning requires destabilization of cell adhesion by JNK signaling. Neuron 88: 926–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H., Perrimon N., 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R. W., Peterson K. A., Johnson M. J., Roix J. J., Welsh I. C., et al. , 2004. Evidence for a conserved function in synapse formation reveals Phr1 as a candidate gene for respiratory failure in newborn mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 1096–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Jones Y., Ellisman M. H., Goldstein L. S., Karin M., 2003. JNK1 is required for maintenance of neuronal microtubules and controls phosphorylation of microtubule-associated proteins. Dev. Cell 4: 521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. A., Wairkar Y. P., Johnson S. L., DiAntonio A., 2006. Highwire restrains synaptic growth by attenuating a MAP kinase signal. Neuron 51: 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza J., Hendricks M., Le Guyader S., Subburaju S., Grunewald B., et al. , 2005. Formation of the retinotectal projection requires Esrom, an ortholog of PAM (protein associated with Myc). Development 132: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eresh S., Riese J., Jackson D. B., Bohmann D., Bienz M., 1997. A CREB-binding site as a target for decapentaplegic signalling during Drosophila endoderm induction. EMBO J. 16: 2014–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulga T. A., Van Vactor D., 2008. Synapses and growth cones on two sides of a highwire. Neuron 57: 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. S., Wang B., Pozniak C. D., Chen M., Watts R. J., et al. , 2011. DLK induces developmental neuronal degeneration via selective regulation of proapoptotic JNK activity. J. Cell Biol. 194: 751–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill B., Murphey R. K., Borgen M. A., 2016. The PHR proteins: intracellular signaling hubs in neuronal development and axon degeneration. Neural Dev. 11: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Xie J., Dang C. V., Liu E. T., Bishop J. M., 1998. Identification of a large Myc-binding protein that contains RCC1-like repeats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 9172–9177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund M., Nix P., Hauth L., Jorgensen E. M., Bastiani M., 2009. Axon regeneration requires a conserved MAP kinase pathway. Science 323: 802–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig C. L., Worrell J., Levine R. B., Ramaswami M., Sanyal S., 2008. Normal dendrite growth in Drosophila motor neurons requires the AP-1 transcription factor. Dev. Neurobiol. 68: 1225–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopfer E. D., McLaughlin T., Watts R. J., Schuldiner O., O’Leary D. D., et al. , 2006. Wlds protection distinguishes axon degeneration following injury from naturally occurring developmental pruning. Neuron 50: 883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs K., Todman M. G., Allen M. J., Davies J. A., Bacon J. P., 2000. Synaptogenesis in the giant-fibre system of Drosophila: interaction of the giant fibre and its major motorneuronal target. Development 127: 5203–5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A., Rubin G. M., Ngo T.-T. B., Shepherd D., Murphy C., et al. , 2012. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2: 991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. T., Zhu S., Younger S., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N., 2006. Identification of E2/E3 ubiquitinating enzymes and caspase activity regulating Drosophila sensory neuron dendrite pruning. Neuron 51: 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch C., Jo J., Wu Y., Fish G. S., Galko M. J., 2010. A targeted UAS-RNAi screen in Drosophila larvae identifies wound closure genes regulating distinct cellular processes. Genetics 186: 943–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewcock J. W., Genoud N., Lettieri K., Pfaff S. L., 2007. The ubiquitin ligase Phr1 regulates axon outgrowth through modulation of microtubule dynamics. Neuron 56: 604–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Kulkarni G., Wadsworth W. G., 2008. RPM-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans protein that functions in presynaptic differentiation, negatively regulates axon outgrowth by controlling SAX-3/robo and UNC-5/UNC5 activity. J. Neurosci. 28: 3595–3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longair M. H., Baker D. A., Armstrong J. D., 2011. Simple neurite tracer: open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics 27: 2453–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon K. P., Carrillo R. A., Zinn K., 2013. Development and plasticity of the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2: 647–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. R., Press C., Daniels R. W., Sasaki Y., Milbrandt J., et al. , 2009. A dual leucine kinase-dependent axon self-destruction program promotes Wallerian degeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 12: 387–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata K., Abrams B., Grill B., Goncharov A., Huang X., et al. , 2005. Regulation of a DLK-1 and p38 MAP kinase pathway by the ubiquitin ligase RPM-1 is required for presynaptic development. Cell 120: 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr B. O., Borgen M. A., Caruccio P. M., Murphey R. K., 2014. Netrin and Frazzled regulate presynaptic gap junctions at a Drosophila giant synapse. J. Neurosci. 34: 5416–5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan P., Nakagawa M., Wilkin M. B., Moffat K. G., O’Kane C. J., et al. , 1996. Mutations in shaking-B prevent electrical synapse formation in the Drosophila giant fiber system. J. Neurosci. 16: 1101–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rallis A., Moore C., Ng J., 2010. Signal strength and signal duration define two distinct aspects of JNK-regulated axon stability. Dev. Biol. 339: 65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rallis A., Lu B., Ng J., 2013. Molecular chaperones protect against JNK- and Nmnat-regulated axon degeneration in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 126: 838–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S., Sandstrom D. J., Hoeffer C. A., Ramaswami M., 2002. AP-1 functions upstream of CREB to control synaptic plasticity in Drosophila. Nature 416: 870–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S., Narayanan R., Consoulas C., Ramaswami M., 2003. Evidence for cell autonomous AP1 function in regulation of Drosophila motor-neuron plasticity. BMC Neurosci. 4: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster C. M., Davis G. W., Fetter R. D., Goodman C. S., 1996. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. II. Fasciclin II controls presynaptic structural plasticity. Neuron 17: 655–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. E., DiAntonio A., 2011. Highwire regulates guidance of sister axons in the Drosophila mushroom body. J. Neurosci. 31: 17689–17700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. E., Cho Y., Beirowski B., Milbrandt J., Cavalli V., et al. , 2012. Dual leucine zipper kinase is required for retrograde injury signaling and axonal regeneration. Neuron 74: 1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanouye M. A., Wyman R. J., 1980. Motor outputs of giant nerve fiber in Drosophila. J. Neurophysiol. 44: 405–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthaman S. B., Godenschwege T. A., Murphey R. K., 2008. A mechanism distinct from highwire for the Drosophila ubiquitin conjugase bendless in synaptic growth and maturation. J. Neurosci. 28: 8615–8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H. I., DiAntonio A., Fetter R. D., Bergstrom K., Strauss R., et al. , 2000. Highwire regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron 26: 313–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts R. J., Hoopfer E. D., Luo L., 2003. Axon pruning during Drosophila metamorphosis: evidence for local degeneration and requirement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Neuron 38: 871–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber U., Paricio N., Mlodzik M., 2000. mediates Frizzled-induced R3/R4 cell fate distinction and planar polarity determination in the Drosophila eye. Development 127: 3619–3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Wairkar Y. P., Collins C. A., DiAntonio A., 2005. Highwire function at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction: spatial, structural, and temporal requirements. J. Neurosci. 25: 9557–9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Collins C. A., 2012. A conditioning lesion protects axons from degeneration via the Wallenda/DLK MAP kinase signaling cascade. J. Neurosci. 32: 610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Wang X., Ewanek R., Bhat P., Diantonio A., et al. , 2010. Protein turnover of the Wallenda/DLK kinase regulates a retrograde response to axonal injury. J. Cell Biol. 191: 211–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Hao Y., Sun K., Li J., Li X., et al. , 2012. The Highwire ubiquitin ligase promotes axonal degeneration by tuning levels of Nmnat protein. PLoS Biol. 10: e1001440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlinger J., Kockel L., Peverali F. A., Jackson D. B., Mlodzik M., et al. , 1997. Defective dorsal closure and loss of epidermal decapentaplegic expression in Drosophila fos mutants. EMBO J. 16: 7393–7401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Q., Wang J., Kim A., Liu Q., Watts R., et al. , 2003. Involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the early stages of wallerian degeneration. Neuron 39: 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen M., Huang X., Bamber B., Jin Y., 2000. Regulation of presynaptic terminal organization by C. elegans RPM-1, a putative guanine nucleotide exchanger with a RING-H2 finger domain. Neuron 26: 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Strains are available upon request. The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.