Abstract

Background

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains one of the most deadly cancers in Europe and the USA. There is consensus that radical tumor surgery is the only viable option for any long-term survival in patients with PDAC. So far, limited data are available regarding the routine surgical management of patients with advanced PDAC in the light of surgical guidelines.

Methods

A national survey on perioperative management of patients with PDAC and currently applied criteria on their tumor resectability in German university and community hospitals was carried out.

Results

With a response rate of 81.6% (231/283) a total of 95 (41.1%) participating departments practicing pancreatic surgery in Germany are certified as competence and reference centers for surgical diseases of the pancreas in 2016. More than 95% of them indicate to carry out structured and interdisciplinary therapies along with an interdisciplinary pre- and postoperative tumor board. The majority of survey respondents prefer the pylorus-preserving partial pancreatoduodenectomy (93.1%) with standard lymphadenectomy for cancer of the pancreatic head. Intraoperative histological evaluation of the resection margins is used regularly by 99% of the survey respondents. 98.7% of survey respondents carry out partial or complete vein resection, 126 respondents (54.5%) would resect tumor adjacent arteries, and 102 respondents (44.2%) would perform metastasectomy if complete PDAC resection (R0) is possible.

Conclusion

Evidence-based and standardized pancreatic surgery is practiced by a large number of hospitals in Germany. However, a significant number of survey respondents support an extended radical tumor resection in patients with advanced PDAC even when not indicated by current clinical guidelines.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is currently the fourth leading cause of cancer related death in western countries, and it is expected to rise to second place behind lung cancer until 2030.[1] In contrast to stable or declining trends for most cancers in Europe since 2009, PDAC shows an increase of 3.6% and 5.2% for men and women, respectively, with predicted death rates of 8.2 and 5.6/100 000 corresponding to 85 300 total deaths in 2015. In Germany low 5-year overall survival rates of 6% for men and 8% for woman are accompanied by similar incidence and mortality rates of about 16 000 people in 2012, making long-term survival rather exceptional.[2, 3] The poor prognosis of PDAC is mainly attributed to rapid disease progression, late diagnosis at advanced unresectable stages, and poor response to current (neo-) adjuvant or palliative regimens.

Oncological surgery with tumor extirpation as the only curative treatment option of PDAC at early stages, so far, is possible in only 15% of PDAC patients with 5-year survival rates below 20%.[4] To date, national and international guidelines for the treatment of PDAC patients differentiate between resectable, borderline resectable, locally advanced unresectable, and metastatic PDAC.[5–7] However, there is a wide range of definitions available for borderline PDAC resectability.

The aim of this study is to generate data regarding the routine surgical management of patients with PDAC in Germany. On the basis of the revised clinical practice guidelines for PDAC surgery of the American NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) in 2015, the European ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) in 2015, and the German AWMF (Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany) in 2013, we carried out a national survey on perioperative management of patients with PDAC and currently applied criteria on their tumor resectability in German university and community hospitals.[5–7] In this context, the daily practice with borderline tumors was of particular interest.

Methods

Study design

A national anonymized survey on surgical management of patients with PDAC in 283 German university and community hospitals was performed between November 2015 and January 2016. Questionnaires, consisting of 12 questions with 1 multiple-choice question, 10 yes/no-questions, and one open question were sent out to all German hospitals reaching a threshold of twelve pancreatic resections per year as documented in the online database www.weisse-liste.de. The addressed heads of the different surgical departments were asked for the number of PDAC surgeries per year, certification as competence and reference center for surgical diseases of the pancreas, implementation of pathways incorporating structured and interdisciplinary therapies along with pre- and postoperative interdisciplinary tumor boards, structured pathways for postoperative clinical treatment, in-house follow-up care, local criteria for tumor resectability with consecutive procedures in advanced PDAC, and implementation of an intraoperative histological evaluation of the resection margins (Table 1). Specifically, they were asked for their decision in case of a preoperatively unknown, but technically resectable distant metastasis during the surgical exploration and pancreatic resection. According to Meguid et al, an annual institution resection volume of 19 or more pancreatic resections was defined as high-volume center.[8] As this survey does not involve clinical research on patients but focuses on quality data of participating survey respondents, the Ethics Commission notes that neither consent nor ethics committee approval is required (Ethics Commission, University Muenster, Az: 2016-515-f-N).

Table 1. Questionnaire consisting of twelve question blocks with a total of 34 parameters.

| 1 | Name of hospital, chief, location, head of pancreatic surgery | Free text |

| Specialized department for pancreatic surgery | Yes / No | |

| 2 | Pancreatic procedures in general / head resections/ other | <12; <20; <50; <100; >100 |

| 3 | DGAV or DKG (OnkoZert) certification / other certification | Yes / No / Free text |

| 4 | Pylorus-preserving- pancreatoduodenectomy / pancreatojejunostomy / pancreatogastrostomy / distal pancreatectomy | Yes / No / Occasionally |

| 5 | Presentation in pre- / postoperative tumorboard | Yes / No / Occasionally |

| 6 | Intraoperative histological evaluation of the resection margins | Yes / No |

| 7 | Intraoperative decision for preoperatively unknown, but technically resectable liver metastasis with estimated R0 / R1 / R2 resection | Yes / No |

| 8 | Intraoperative decision for preoperatively unknown, but technically resectable peritoneal metastasis with estimated R0 / R1 / R2 resection | Yes / No |

| 9 | Intraoperative decision for venous infiltration with estimated R0 / R1 / R2 resection | Yes / No |

| 10 | Intraoperative decision for arterial infiltration with estimated R0 / R1 / R2 resection | Yes / No |

| 11 | Decision if guidelines do not recommend continuation of resection | Free text |

| 12 | Clinical pathway / in-house follow-up care / guideline audit | Yes / No |

Statistical analysis

All returning questionnaires were collected by our study nurse at the Department of General and Visceral Surgery of the University Hospital Muenster. Statistical data analysis was performed in cooperation with our Institute of Biostatistics and Clinical Research using SPSS® Statistics Version 22 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY) for Windows®. We used the Fisher two-tailed exact test and whenever appropriate the χ2 test for contingency tables. All of the variables were dichotomized. P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Survey respondents

A total of 231 of 283 questionnaires that were sent out were completed and returned. This corresponds to a response rate of 81.6%. 11.3% of the responding surgical departments with their own divisions of pancreatic surgery were located at German university hospitals and 88.7% at German community hospitals. In 2014, pancreatic surgery procedures were performed in more than 100 patients per year by 16 departments, in 50 to 100 patients per year by 23 departments, in 20 to 50 patients per year by 102 departments, in 12 to 20 patients per year by 55 departments, and in less than 12 patients per year by 10 responding surgical departments. Pancreatoduodenectomy in particular was performed in most surgical institutions of survey respondents (97%) using the pylorus-preserving partial pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD) by Traverso—Longmire or the Classic (Kausch-)Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy (CWPD). Pancreatic head resections by PPPD was preferred by 215 (93.1%) survey respondents. 189 survey participants (81.8%) preferred the pancreatojejunostomy technique over pancreatogastrostomy (27.3%). In patients with pancreatic body or tail pathologies, 224 survey respondents (97%) would perform a distal pancreatectomy.

Capacity levels, case load and certification

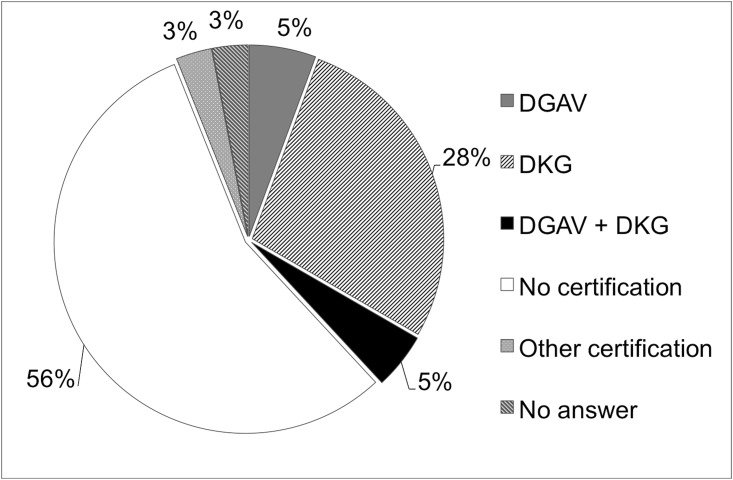

Higher capacity levels corresponded with higher case load (p< 0.0001), that correlated with certification status as competence and reference center for surgical diseases of the pancreas (p< 0.0001), tested and awarded among others by the German Association for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) or the German Cancer Association (DKG). Overall 75 survey respondents (32.5%) were certified by the DKG, 24 (10.4%) were certified by the DGAV, 7 (3%) stated to be certified by other oncological societies, 129 surgical departments (55.8%) were not certified, and 7 survey respondents (3%) did not provide any information to this topic (Fig 1). However, 96.1% of the survey respondents indicate to carry out structured and interdisciplinary therapies along with an interdisciplinary pre- and postoperative tumor board, an internal guideline audit (45%), and a standard postoperative care (86,1%) according to the AWMF guidelines.

Fig 1. Certification status.

Certification of survey respondents as competence and reference center for surgical diseases of the pancreas.

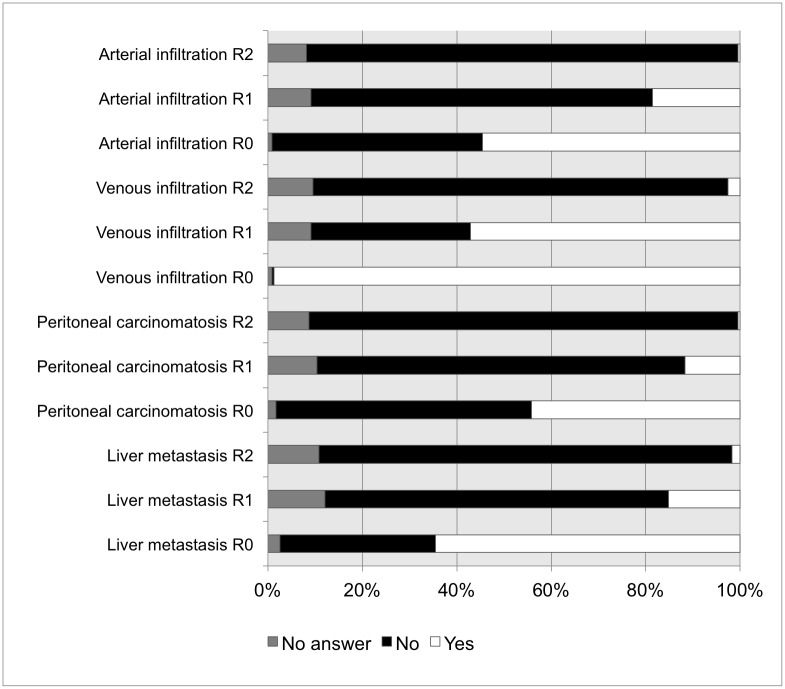

Surgical criteria for resectability

54.5% of the survey respondents consider the presence of peritoneal metastasis as the most important criterion for non-resectability of PDAC. However, 102 departments (44.2%) would perform metastasectomy if complete resection (R0) is possible. Microscopic residual tumor (R1) would be accepted by 26 departments (11.3%), macroscopic residual tumor (R2) by 1 department (0.4%), depending on the individual case (Fig 2). Intraoperative histological evaluation of the resection margins is used regularly by 99% of the responding surgical departments. In case of technically resectable liver metastasis, 64.5% of the survey respondents would remove them if R0 is possible. Some survey respondents would carry out resection of liver metastasis, even if only R1 (15.2%) or R2 (1.7%) results are possible. PDAC infiltration of adjacent arteries is regarded as resectable by 126 respondents (54.5%) if R0 is possible. Depending on the individual case, some departments would perform arterial resection, even if only R1 (18.6%) or R2 (0.4%) results are possible. In case of singular venous PDAC infiltration, a majority of 98.7% of survey respondents carry out partial or complete vein resection in curative intention, whereas 57.1% / 2.6% would even accept a possible R1 / R2 situation, respectively.

Fig 2. Criteria for tumor resectability.

Intraoperative decision and percentages of surgical (non-) resectability in PDAC.

A total of 9 different answers of the survey respondents (81.2%) can be categorized with regard to the open question of the survey about their approach to advanced tumor, in which the guidelines recommend no further resection: Termination of further tumor resection in accordance with the guidelines in 31.2%, case-dependent individual decision of the surgeon in 29.0%, consultation of the surgical head of the department in 7.8%, interdisciplinary consultation of e.g. oncologist or pathologist in 3.9%, and continuation of tumor resection in 1.3%.

Subgroup analyses reveal that a case load at high volume centers with more than 20 pancreatoduodenectomies in 2014 has influence on treatment decisions. The assessment of technically resectable distant metastasis and local vascular tumor infiltration differed significantly between survey respondents of high and low volume hospitals with resection rates of 50% versus 12.9% (p = 0.023) for liver metastasis, and resection rates of 92.3% versus 43.3% (p = 0.007) for venous PDAC infiltration.

Discussion

Radical surgery is still regarded as the best option for potentially curative treatment and long-term survival in patients with PDAC.[9, 10] However, the resection rate with curative intent remains less than 20%.[1] Redefining of locally advanced non-metastatic PDAC into borderline resectable disease and non-resectable disease is an approach to maximize the option of a personalized curative attempt for PDAC patients who were previously considered to have unresectable disease.[11] To improve the rate of complete resection of the primary tumor to microscopically negative margins, an expert consensus group has developed criteria to define tumour resectability that were adopted to current national clinical practice guidelines.[5–7, 10–13] These imaging-based criteria for borderline resectability include no distant mestastasis with safe resection and reconstruction of (1) short segment venous involvement of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein (PV), and (2) arterial segment involvement of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or celiac trunk <180° or gastroduodenal artery encasement up to the hepatic artery with no extension to the celiac axis. Although computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging are able to determine PDAC non-resectability with a high positive predictive value of >90%, their predictive value to affirm resectability in less than 50% is insufficient.[14] Furthermore, the lack of consensus with regard to objective definition and therapeutic algorithm put borderline PDAC at risk of being classified falsely as unresectable disease stage.

In this national survey, we demonstrate and analyse the routine surgical management of patients with PDAC in 231 German university and community hospitals practicing pancreatic surgery. This high response rate of 81.6% reflects the actual surgical treatment of PDAC in Germany and its accordance with the current consensus-based recommendations suggested by the clinical practice guidelines for PDAC surgery. Interestingly, it seems that different opinions on the definition to technically resectable PDAC exist. A significant number of responding departments would perform resection of preoperatively unknown, but technically resectable liver metastasis in 64.5%, resection and reconstruction of tumor-adjacent arterial encasement in 54.5%, and even metastasectomy in 44.2%, if radical tumor resection is possible. These results represent a progressive surgical approach of many survey respondents to resect advanced PDACs including potentially R0-resectable peritoneal or liver metastases in highly selected patients. Indeed, the evidence for this indication is limited. However, very recent data suggest improved survival for patients undergoing synchronous resections of PDAC and single liver or pulmonary metastases.[15–17] Obviously, the resection of the primary tumor and synchronous liver or peritoneal metastases is not recommended by current national and international guidelines for the treatment of PDAC. In such palliative cases, chemotherapeutic regimes with FOLFIRNOX or gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel have been established showing increased overall survival with a median of up to 11 months. With increasing safety of operations and persisting unsatisfying oncologic outcome in PDCA patients even in early stages, extension of localized approaches in pancreatic surgery, partially combined with neo-adjuvant treatment is documented in the literature. There is mounting evidence that high volume pancreas centers support the potential benefit of surgical intervention with macroscopically complete resection in highly selected patients with locally advanced or metastatic PDAC. In recent years, small retrospective studies and case reports including highly selected patients in good general condition suggest that extended resections of PDAC and even of distant diseased lymph nodes and liver metastases can be performed safely with improved survival.[15, 18–26] However, randomized controlled trials on this issue are lacking so far. In contrast, there is wide acceptance that mesenterico-portal resection ranging from partial venous excision to segmental resection is recommended in PDAC with single venous infiltration allowing safe resection and reconstruction.[27–29]

Overall, there is broad international variation of borderline PDAC treatment. The great majority of survey respondents prefer the direct operative exploration for potential resection versus 0.4% suggesting a downstaging by neoadjuvant therapy. Recently, a systematic review by Tang et al. including trials with prospective design could reveal similar R0 resection and survival rates in borderline resectable PDAC patients after neoadjuvant therapy and in resectable PDAC patients, much higher than those in unresectable tumor patients. It is noteworthy that 63% of PDAC patients initially staged as borderline resectable could be resected successfully after neoadjuvant therapy with a median survival amounted to 25.9 months (range 21.1–30.7).[30] Common definition and treatment algorithm for borderline resectable PDAC should be applied in future trials.

As expected, the decision of survey respondents for radical surgical resection even in advanced tumor stages with potentially resectable venous or arterial infiltration and even solitairy R0 resectable hepatic or peritoneal metastasis correlates with the establishment of experienced high-volume centers. Several studies could demonstrate that pancreatectomy performed at high volume PDAC treatment centers by high-volume surgeons improves short- and long-term outcomes.[31, 32] However, therapy strategies currently not recommended by scientific evidence should be offered to PDAC patients with advanced tumor stage only within controlled clinical trials.

Pancreatoduodenectomy, preferentially PPPD, is performed in German hospitals of all capacity levels, ranging from university hospitals to community hospitals with caseloads varying from under twelve to over a hundred of annual pancreatoduodenectomies. However, less than 42% of the responding surgical departments declare to be certified as competence center for surgical diseases of the pancreas, and only 45% have an internal guideline audit. After all, 95% of the survey respondents indicate to carry out structured and interdisciplinary therapies along with an interdisciplinary pre- and postoperative tumor board, and at least 86.1% perform standard postoperative care with implementation of structured pathways for postoperative clinical treatment, in-house follow-up care for PDAC, and guideline audits according to the national guidelines. It is well known that clinical certification by accredited expert panels with implementation of clinical pathways are associated with improved professional practice and patient outcomes as well as reduced length of hospital stay and hospital costs.[33, 34]

Although pancreatic surgery is offered by a large number of hospitals in Germany, a significant number of survey respondents support an extended radical tumor resection in patients with advanced PDAC even when not indicated by the current clinical guidelines. Surgical treatment with curative intend of patients with advanced PDAC should be recommended only in the setting of prospective trials at certified high-volume competence and reference centers for surgical diseases of the pancreas.

Acknowledgments

We thank the responsible surgical heads of the participating surgical clinics contributing to this study survey. The authors thank particularly our study secretary Mrs Ulrike Kein for her support and expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AWMF

Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany

- CHA

Common hepatic artery

- CWPD

Classic (Kausch-)Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy

- DGAV

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie, German Association for General and Visceral Surgery

- DKG

Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, German Cancer Association

- ESMO

European Society for Medical Oncology

- GA

Gastroduodenal artery

- ISGPS

International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PPPD

Pylorus-preserving partial pancreatoduodenectomy by Traverso—Longmire

- PV

portal vein

- SMA

superior mesenteric artery

- SMV

superior mesenteric vein

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. Epub 2016/01/09. 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Rosso T, Rota M, Levi F, La Vecchia C, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2015: does lung cancer have the highest death rate in EU women? Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):779–86. Epub 2015/01/28. 10.1093/annonc/mdv001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International journal of cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86. Epub 2014/09/16. 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):607–20. Epub 2011/05/31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Behrman SW, Benson AB 3rd, Casper ES, Chiorean EG, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2014: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(8):1083–93. Epub 2014/08/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, Burtin P, Goere D, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26 Suppl 5:v56–68. Epub 2015/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seufferlein T, Porzner M, Becker T, Budach V, Ceyhan G, Esposito I, et al. [S3-guideline exocrine pancreatic cancer]. Z Gastroenterol. 2013;51(12):1395–440. Epub 2013/12/18. 10.1055/s-0033-1356220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meguid RA, Ahuja N, Chang DC. What constitutes a "high-volume" hospital for pancreatic resection? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(4):622 e1–9. Epub 2008/04/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi R, Imamura M, Hosotani R, Imaizumi T, Hatori T, Takasaki K, et al. Surgery versus radiochemotherapy for resectable locally invasive pancreatic cancer: final results of a randomized multi-institutional trial. Surg Today. 2008;38(11):1021–8. Epub 2008/10/30. 10.1007/s00595-007-3745-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, Seiler CA, Friess H, Buchler MW. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91(5):586–94. Epub 2004/05/04. 10.1002/bjs.4484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bockhorn M, Uzunoglu FG, Adham M, Imrie C, Milicevic M, Sandberg AA, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2014;155(6):977–88. Epub 2014/05/27. 10.1016/j.surg.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, Talamonti MS, William Traverso L, Linehan DC. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(7):1727–33. Epub 2009/04/28. 10.1245/s10434-009-0408-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans DB, Farnell MB, Lillemoe KD, Vollmer C Jr., Strasberg SM, Schulick RD. Surgical treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreas cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(7):1736–44. Epub 2009/04/24. 10.1245/s10434-009-0416-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong JC, Lu DS. Staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by imaging studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(12):1301–8. Epub 2008/10/25. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tachezy M, Gebauer F, Janot M, Uhl W, Zerbi A, Montorsi M, et al. Synchronous resections of hepatic oligometastatic pancreatic cancer: Disputing a principle in a time of safe pancreatic operations in a retrospective multicenter analysis. Surgery. 2016;160(1):136–44. Epub 2016/04/07. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crippa S, Bittoni A, Sebastiani E, Partelli S, Zanon S, Lanese A, et al. Is there a role for surgical resection in patients with pancreatic cancer with liver metastases responding to chemotherapy? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016. Epub 2016/07/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruger S, Haas M, Burger PJ, Ormanns S, Modest DP, Westphalen CB, et al. Isolated pulmonary metastases define a favorable subgroup in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2016;16(4):593–8. Epub 2016/04/14. 10.1016/j.pan.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hackert T, Niesen W, Hinz U, Tjaden C, Strobel O, Ulrich A, et al. Radical surgery of oligometastatic pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016. Epub 2016/11/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crippa S, Bittoni A, Sebastiani E, Partelli S, Zanon S, Lanese A, et al. Is there a role for surgical resection in patients with pancreatic cancer with liver metastases responding to chemotherapy? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(10):1533–9. Epub 2016/07/18. 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.06.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrikhande SV, Kleeff J, Reiser C, Weitz J, Hinz U, Esposito I, et al. Pancreatic resection for M1 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(1):118–27. Epub 2006/10/27. 10.1245/s10434-006-9131-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellon E, Gebauer F, Tachezy M, Izbicki JR, Bockhorn M. Pancreatic cancer and liver metastases: state of the art. Updates Surg. 2016;68(3):247–51. Epub 2016/11/11. 10.1007/s13304-016-0407-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaib WL, Ip A, Cardona K, Alese OB, Maithel SK, Kooby D, et al. Contemporary Management of Borderline Resectable and Locally Advanced Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21(2):178–87. Epub 2016/02/03. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conroy T, Bachet JB, Ayav A, Huguet F, Lambert A, Caramella C, et al. Current standards and new innovative approaches for treatment of pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:10–22. Epub 2016/02/07. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buc E, Orry D, Antomarchi O, Gagniere J, Da Ines D, Pezet D. Resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with synchronous distant metastasis: is it worthwhile? World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:347 Epub 2014/11/20. 10.1186/1477-7819-12-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michalski CW, Erkan M, Huser N, Muller MW, Hartel M, Friess H, et al. Resection of primary pancreatic cancer and liver metastasis: a systematic review. Dig Surg. 2008;25(6):473–80. Epub 2009/02/13. 10.1159/000184739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zanini N, Lombardi R, Masetti M, Giordano M, Landolfo G, Jovine E. Surgery for isolated liver metastases from pancreatic cancer. Updates Surg. 2015;67(1):19–25. Epub 2015/02/24. 10.1007/s13304-015-0283-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Li B, Xu D. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric vein-portal vein resection for pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2012;36(4):884–91. Epub 2012/02/22. 10.1007/s00268-012-1461-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly KJ, Winslow E, Kooby D, Lad NL, Parikh AA, Scoggins CR, et al. Vein involvement during pancreaticoduodenectomy: is there a need for redefinition of "borderline resectable disease"? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(7):1209–17; discussion 17. Epub 2013/04/27. 10.1007/s11605-013-2178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu XZ, Li J, Fu DL, Di Y, Yang F, Hao SJ, et al. Benefit from synchronous portal-superior mesenteric vein resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):371–8. Epub 2014/02/25. 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang K, Lu W, Qin W, Wu Y. Neoadjuvant therapy for patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of response and resection percentages. Pancreatology. 2016;16(1):28–37. Epub 2015/12/22. 10.1016/j.pan.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshioka R, Yasunaga H, Hasegawa K, Horiguchi H, Fushimi K, Aoki T, et al. Impact of hospital volume on hospital mortality, length of stay and total costs after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2014;101(5):523–9. Epub 2014/03/13. 10.1002/bjs.9420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2117–27. Epub 2003/12/03. 10.1056/NEJMsa035205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, Machotta A, Willis J, Snow P, et al. The effects of clinical pathways on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay, and hospital costs: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof. 2012;35(1):3–27. Epub 2011/05/27. 10.1177/0163278711407313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller MK, Dedes KJ, Dindo D, Steiner S, Hahnloser D, Clavien PA. Impact of clinical pathways in surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(1):31–9. Epub 2008/06/04. 10.1007/s00423-008-0352-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.