SUMMARY

Synaptojanin 1 (SJ1) is a major presynaptic phosphatase that couples synaptic vesicle endocytosis to the dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2, a reaction needed for the shedding of endocytic factors from their membranes. While the role of SJ1’s 5-phosphatase module in this process is well established, the contribution of its Sac phosphatase domain, whose preferred substrate is PI4P, remains unclear. Recently a homozygous mutation in its Sac domain was identified in early-onset Parkinsonism patients. We show that mice carrying this mutation developed neurological manifestations similar to those of human patients. Synapses of these mice displayed endocytic defects and a striking accumulation of clathrin coated intermediates strongly implicating Sac domain’s activity in endocytic protein dynamics. Mutant brains had elevated auxilin (PARK19) and parkin (PARK2) levels. Moreover, dystrophic axonal terminal changes were selectively observed in dopaminergic axons in the dorsal striatum. These results strengthen evidence for a link between synaptic endocytic dysfunction and Parkinson’s disease.

INTRODUCTION

Several recent studies have revealed a link between proteins that participate in synaptic vesicle endocytic recycling, clathrin mediated endocytosis in particular, and early onset Parkinsonism (EOP) (Edvardson et al., 2012; Koroglu et al., 2013; Krebs et al., 2013; Olgiati et al., 2014; Olgiati et al., 2016; Quadri et al., 2013; Schreij et al., 2016).

One such protein is synaptojanin 1 (SJ1). SJ1 is a polyphosphoinositide phosphatase expressed at high level in neurons and concentrated at synapses (McPherson et al., 1996). It contains a N-terminal Sac1 PI4P phosphatase domain (Sac domain) that can also dephosphorylate PI3P and PI(3,5)P2 (Guo et al., 1999; Nemoto et al., 2001), a central 5-phosphatase domain that can dephosphorylate PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, an RNA recognition motif (RRM) (Pirruccello and De Camilli, 2012) and an extended unstructured C-terminal Proline-Rich Domain (PRD) (McPherson et al., 1996).

A main function of SJ1 is to couple the endocytic reaction to the dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2, a plasma membrane-enriched phosphoinositide, by sequentially removing the 5 and 4 phosphate of PI(4,5)P2 via its two phosphatase domains (Cremona et al., 1999; Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006; McPherson et al., 1996). Such dephosphorylation is critical for the shedding of the clathrin coat and other endocytic factors, and may also have a role in the fission reaction. Recruitment of SJ1 to endocytic sites is mediated by interactions of its PRD with a variety of SH3 domain-containing endocytic proteins, primarily endophilin (de Heuvel et al., 1997; Ringstad et al., 1997), whose assembly at the neck of endocytic pits is facilitated by its curvature sensing/generating properties (Farsad et al., 2001; Peter et al., 2004). Accordingly, genetic deletion of either synaptojanin or endophilin in mouse neurons leads to synaptic transmission defects (Cremona et al., 1999; Luthi et al., 2001; Milosevic et al., 2011). Such defects correlate with a lower abundance of synaptic vesicles in nerve terminals, delayed synaptic vesicle endocytic recycling detectable by a pHluorin assay and the accumulation of clathrin coated vesicles (CCVs)(Cremona et al., 1999; Hayashi et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2002; Mani et al., 2007; Milosevic et al., 2011). Similar defects have been observed in other model organisms (Dickman et al., 2006; Harris et al., 2000; Schuske et al., 2003; Van Epps et al., 2004; Verstreken et al., 2003).

At the organismal level, complete loss of SJ1 results in early postnatal lethality in mice (hours or few days after birth) (Cremona et al., 1999) and humans (death during childhood and severe epilepsy) (Dyment et al., 2015; Hardies et al., 2016). However, a homozygous missense R258Q mutation within the Sac domain of SJ1 has been recently identified in 6 patients with autosomal recessive EOP from 3 independent families, leading to define SJ1 as PARK20 (Krebs et al., 2013; Olgiati et al., 2014; Quadri et al., 2013). In these patients Parkinson-like symptoms developed in early adulthood (20–30’s) and 4 of them additionally suffered from epilepsy (Drouet and Lesage, 2014). This finding is of striking interest, as loss-of-function mutations in the gene DNAJC6 that encode auxilin, another protein that functions in the uncoating of endocytic CCVs (Fotin et al., 2004; Ungewickell et al., 1995), are also responsible for autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson’s disease (PD) and sporadic cases of PD, leading to define auxilin as PARK19 (Edvardson et al., 2012; Koroglu et al., 2013; Olgiati et al., 2016). Based on studies of the purified protein, the EOP mutation of SJ1 (SJ1 R->Q) selectively abolishes the phosphatase activity of the Sac domain without affecting the activity of the 5-phosphatase domain (Krebs et al., 2013).

The role of the Sac domain of SJ1 in the function of the synapse remains elusive. Rescue experiments of SJ1 knockout (KO) neurons with Sac phosphatase-defective or 5-phosphatase defective SJ1 constructs revealed contribution of both phosphatase domains to endocytosis (as assessed by pHluorin-based assays), but with a dominant role of 5-phosphatase domain (Mani et al., 2007). Recent study in C. elegans suggested a non-catalytic function of the Sac domain in synaptic targeting of SJ1 (Dong et al., 2015). Whether the activity of Sac domain is important for the function of SJ1 in clathrin uncoating is still an open question, which acquires more relevance in view of the phenotypic similarities produced in human patients by mutations in auxilin and in the Sac domain of SJ1. To address this question, and more generally to explore mechanisms of disease in EOP patients with the SJ1 Sac domain mutation, we generated knock-in (KI) mice carrying the same mutation at the corresponding position in the mouse protein (a.a. 259). As in the case of patients, mutant mice have motor defects and epilepsy. In all brain regions of these mice examined, as well as in cultured neurons, most synapses, and more so inhibitory synapses, revealed an abnormal accumulation of clathrin coated intermediates, primarily CCVs, thus implicating the function of the Sac domain of SJ1 in clathrin coat dynamics. Importantly, additional post-developmental structural alterations were observed in a subset of dopaminergic (DAergic) nerve terminals in the dorsal (but not the ventral) striatum of KI brains. These dystrophic changes in the nigrostriatal pathway may explain the occurrence of EOP in human patients.

RESULTS

SJ1 Knock-in (SJ1RQ-KI) mice have neurological manifestations reminiscent of EOP

In order to prove causality of the mutation and to understand mechanisms of disease, we generated homozygous Knock-In (KI) mice (referred to henceforth as SJ1RQ-KI mice) carrying this mutation (Figure. S1A-C). SJ1RQ-KI mice were born in slightly less than normal Mendelian ratio (+/+:+/KI:KI/KI = 50:113:36 from 22 litters). Heterozygous (+/KI) mice had normal body size and exhibited no obvious abnormalities. In contrast, homozygous KI mice showed variable neurological defects.

About 10% of SJ1RQ-KI mice had a very obvious smaller body size relative to littermate controls (Figure. 1A). They also had abnormal posture at rest (Figure. S1D), abnormal unsteady gait and severe movement problems (Movie S1), and generally died within 3 weeks. The remaining mice (90%) SJ1RQ-KI mice started to exhibit tonic-clonic seizures at the 3rd-4th postnatal week. Seizures occurred spontaneously but could also be triggered by manipulations or exposure to a novel environment (Movie S2). In some cases, these seizures resulted in sudden death. About 60% of all the SJ1RQ-KI mice survived to adulthood (Figure. 1B), but developed motor defects in addition to epilepsy. At 2–3 months they started to exhibit the hindlimb clasping phenotype (Figure. 1C–E and Movie S3), which is often observed in mice affected by neurodegenerative conditions, such as PD, Huntington’s disease and cerebellar ataxia. Although adult SJ1RQ-KI mice had normal gait, as assessed by the footprint test (Figure. S1F–I), their performance relative to control littermates in several motor function/coordination tests was substantially impaired: i) they fell much earlier from the accelerated rotarod (Figure. 1F and Movie S4), ii) they had a much higher number of footslips in the balance beam test (Figure. 1G, S1E and Movie S5) and iii) had a worse performance in the grip test (Figure. 1H). Taken together, these results indicate that SJ1RQ-KI mice represent a good animal model to study mechanisms underlying the neurological manifestations resulting from the SJ1RQ patient mutation.

Figure 1. Neurological defects in SJ1RQ-KI mice.

(A) 3-week old SJ1-RQ knock-in homozygous (SJ1RQ-KI) mouse and heterozygous littermate controls (+/KI).

(B) Survival curves of SJ1RQ-KI and wild-type (WT) control mice (n=37).

(C) Hindlimb clasping (HLC) phenotype in 16-week old SJ1RQ-KI mouse.

(D) Quantification of the time spent in clasping during 30 s of tail suspension (n=7).

(E) Quantification of the number of clasping during 30 s of tail suspension (n=7).

(F) Performance on accelerated rotarod of SJ1RQ-KI mice (n=7) in 5 consecutive trials.

(G) Number of missteps (footslips) in the balance beam test (20mm width) (n=7).

(H) Time to fall from a suspended grid (n=7).

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Increased levels of several endocytic factors and of parkin in the brains of SJ1RQ-KI mice

To begin assess the potential impact of the SJ1RQ mutation in brain, we examined by western blotting whether levels of other major neuronal proteins, primarily synaptic and endocytic proteins, were affected. Changes in the proteome upon perturbation of a given gene often provide insight into the impact of the mutation.

Levels of mutant SJ1 (SJ1RQ) were the same as those of WT SJ1 in littermate controls, speaking against an effect of the mutation on its stability or expression (Figure. 2). However, the levels of two proteins that participate in the recruitment of SJ1 to endocytic membranes (endophilin A1 and amphiphysin 1 and 2) (Cremona et al., 1999; Di Paolo et al., 2002; Gad et al., 2000; Milosevic et al., 2011) were increased, suggesting compensatory up-regulation. The levels of auxilin (PARK19), the DNAJ domain containing protein that functions as a cofactor for HSC70 (Fotin et al., 2004; Ungewickell et al., 1995) in clathrin uncoating at synapses were also increased (Figure. 2). This was most interesting, as the function of auxilin and HSC70 are synergistic to those of SJ1 in the shedding of the clathrin coat (Cremona et al., 1999; Eisenberg and Greene, 2007; Yim et al., 2010). The levels of a variety of other neuronal and endocytic proteins tested were the same in SJ1RQ-KI mice and control mice (Figure. 2 and S1J–K). The specific impact of the SJ1RQ mutation on endocytic proteins provides evidence for a role of its Sac domain in endocytosis.

Figure 2. Modified levels of several endocytic proteins in brains of SJ1RQ-KI mice.

(A) Western blot analysis of a variety of endocytic proteins, including SJ1 itself and of parkin in WT and SJ1RQ-KI brains.

(B) Quantification of expression levels of the proteins shown in (A) from at least three independent pairs of samples. Note upregulation of several endocytic proteins and of parkin. Protein levels were normalized to the level of actin. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

See also Figure S1 for additional data.

Importantly, a robust elevation of the level of the E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin, another PD gene (PARK2) (Shimura et al., 2000), was observed in the brain of SJ1RQ-KI mice (Figure. 2), suggesting a link between the functions of SJ1 and of parkin. A similar up-regulation of parkin was observed in mice lacking expression of the endophilins (Cao et al., 2014), which are the major SJ1 interactors (de Heuvel et al., 1997; Ringstad et al., 1997) and also directly bind parkin (Cao et al., 2014; Trempe et al., 2009). Levels of LRRK2, α-synuclein and vps35 (Schreij et al., 2016), three other PD-linked genes, were unchanged (Figure. S1J–K).

Massive clustering of endocytic proteins at nerve terminals of SJ1RQ-KI neurons

An impact of the SJ1RQ mutation on endocytic mechanisms at synapses was further assessed by immunofluorescence staining for endocytic proteins on cultured cortical neurons derived from newborn control and SJ1RQ-KI mice. As we have shown previously for synapses of dynamin, synaptojanin and endophilin KO neurons (Ferguson et al., 2007; Hayashi et al., 2008; Milosevic et al., 2011; Raimondi et al., 2011), a stalling/accumulation of clathrin coated endocytic intermediates (coated pits in the case of dynamin KO mice and coated vesicles in the case of endophilin and synaptojanin KO mice) is reflected in a clustering of endocytic factors immunoreactivity. Immunofluorescence staining of SJ1RQ-KI neuronal cultures revealed a striking synaptic clustering of several endocytic proteins examined, including clathrin, the clathrin adaptor AP2, auxilin, endophilin 1 and amphiphysin1 and 2 (Figure. 3B–E and S2A–B). SJ1 itself (SJ1RQ) was highly clustered in mutant cultures (Figure. 3A). This phenotype could be already observed at DIV7 (Figure. S2C) and became more prominent at DIV19. No obvious difference was observed in the localization of synaptophysin, a marker of intrinsic protein of synaptic vesicles, indicating that the change did not reflect an increased concentration of synaptic vesicle membrane at synapses (Figure. S2D). Likewise, no major change was observed in the distribution of major organelle markers, such as EEA1 (endosomes), LAMP1 (lysosomes) and GM130 (Golgi complex) (Figure. S2D).

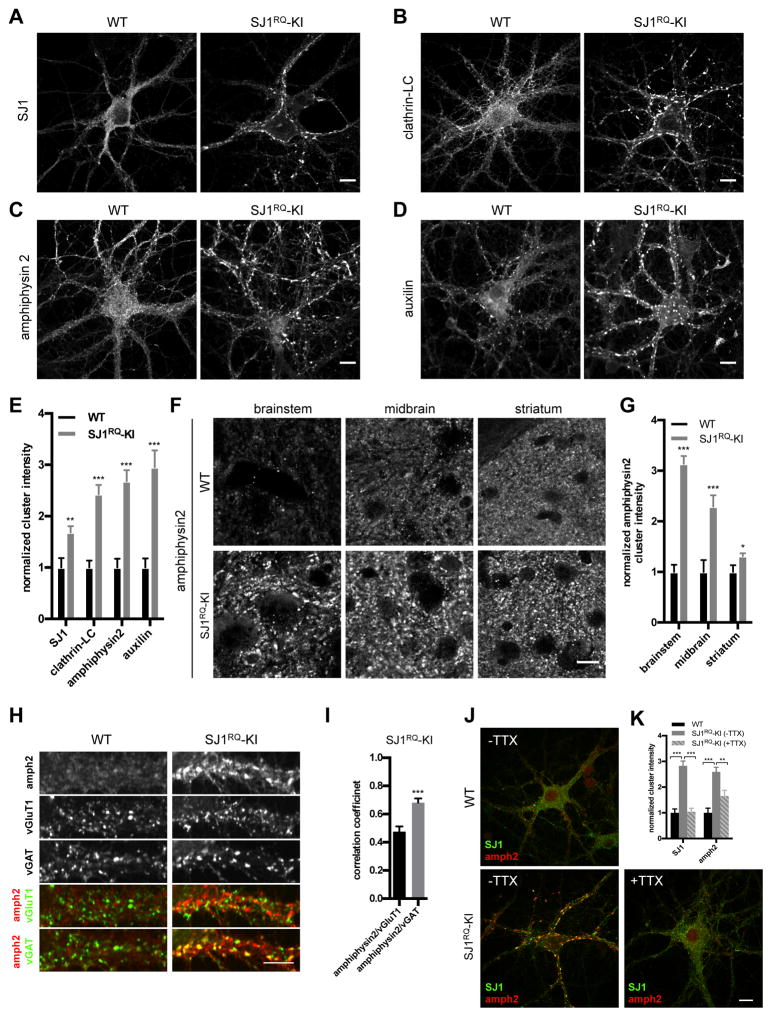

Figure 3. Clustering of SJ1 and other endocytic proteins at SJ1RQ-KI synapses as revealed by immunofluorescence.

(A–D) Representative images of immunoreactivity for SJ1, clathrin light chain (LC), amphiphysin 2 and auxilin in DIV18 cortical neuronal cultures from WT and SJ1RQ-KI newborn mice. Scale bar: 10μm

(E) Quantification of the synaptic clustering of endocytic proteins shown in A–D. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (SJ1: WT n=30, SJ1RQ-KI n=30; clathrin-LC: WT n=21; SJ1RQ-KI n=21; amphiphysin2: WT n=35; SJ1RQ-KI n=32; auxilin: WT n=26; SJ1RQ-KI n=21).

(F) Enhanced clustering of amphiphysin 2 in different regions of frozen brain sections from 8-month old SJ1RQ-KI mice compared to littermate WT controls. Scale bar: 10μm

(G) Quantification of amphiphysin 2 clustering shown in F. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. (brainstem: WT n=20, SJ1RQ-KI n=20; midbrain: WT n=15, SJ1RQ-KI n=15; striatum: WT n=19, SJ1RQ-KI n=25).

9(H) Triple staining of amphiphysin 2, vGluT1 (excitatory presynaptic marker) and vGAT (inhibitory presynaptic marker) in DIV19 WT and SJ1RQ-KI cortical neurons. The merged images of amphiphysin 2 with vGluT1, or with vGAT, are shown separately, revealing greater colocalization of amphiphysin 2 with vGAT than vGluT1 in SJ1RQ-KI neurons. Scale bar: 10μm

(I) Correlation coefficient analysis showing that amphiphysin 2 co-localizes better with vGAT than with vGluT1 in SJ1RQ-KI (n=15). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001.

(J) Double staining of SJ1 and amphiphysin 2 in DIV20 WT control (without TTX) and SJ1RQ-KI cortical neuronal cultures without or with 1μM TTX treatment overnight. Scale bar: 10μm

(K) Quantification of SJ1 and amphiphysin 2 clustering shown in J. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (WT (−TTX) n=20, SJ1RQ-KI (−TTX) n=30, SJ1RQ-KI (+TTX) n=29).

See also Figure S2 for additional data.

Clustered synaptic immunoreactivity for endocytic proteins at SJ1RQ-KI synapses was further observed in the nervous tissue in situ as shown by immunofluorescence for clathrin, amphiphysin 1 and 2 on frozen adult brain sections (Figure. 3F–G and S2E). Such phenotype was observed in different brain regions examined, including brainstem, dorsal midbrain, dorsal and ventral striatum, cortex, hippocampus and deep cerebellar nuclei.

Both in culture and in situ, the clustering phenotype was generally more prominent at inhibitory than at excitatory synapses, as revealed by a greater colocalization of puncta of endocytic proteins with vGAT (a marker of inhibitory nerve terminals) than with vGluT1 (a marker of excitatory synapses) (Figure. 3H–I and S2F). A similar stronger phenotype at inhibitory synapses was previously observed in KO neurons for dynamin1 and SJ1 (Hayashi et al., 2008). Most probably, this is explained by the tonic firing pattern at most inhibitory synapses. This makes them more dependent upon the efficiency of endocytic vesicle recycling and thus more prone to a buildup of endocytic intermediates when mechanisms underlying the progression of these intermediates to the next membrane traffic stage fail. Supporting the possibility, endocytic protein clustering was activity-dependent, as it was partially reversed by overnight treatment with TTX to silencing neuronal activity (Figure. 3J–K). A more severe impact of the SJ1RQ mutation on inhibitory synapses, leading to an altered balance between excitatory and inhibitory transmission, possibly explains the occurrence of epilepsy in mice and patients.

Accumulation of clathrin coated intermediates at presynaptic terminals

To gain direct insight about structural changes that occur in nerve terminals of SJ1RQ-KI neurons, conventional electron microscopy (EM) was performed on brains of 4-month-old mice. In all regions examined, including dorsal/ventral striatum, cerebellar cortex, deep cerebellar nuclei and brainstem, a much greater abundance of clathrin coated vesicular profiles was observed at synapses of SJ1RQ-KI neurons relative to controls (Figure. 4A–D and S3A). The overwhelming majority of these profiles were not adjacent to the plasma membrane in the plane of the section, suggesting that at least most of them were CCVs, although a few clathrin coated pits were also observed (Figure. S3B–C).

Figure 4. Accumulation of CCVs at SJ1RQ-KI synapses.

(A–B) EM ultrastructure of nerve terminals from two different brain regions as indicated of WT and SJ1RQ-KI mice. Note in mutant nerve terminals the abundant presence of CCVs (red arrowheads and insets), which are observed only rarely in WT nerve terminals (no obvious ones in the images shown). Synaptic vesicle number is greatly reduced in mutant synapses where they form only very small clusters (white asterisks). Scale bar: 500nm (inset: 100nm)

(C–D) Quantification of the number of synaptic vesicles (SVs) and CCVs per synaptic area in deep cerebellar nuclei (C) (WT n=45, SJ1RQ-KI n=39) and dorsal striatum (D) (WT n=43, SJ1RQ-KI n=54) of WT and SJ1RQ-KI mouse brains.

Each dot represents one synapse. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001.

See also Figure S3 for additional data.

The number of synaptic vesicles was decreased accordingly (Figure. 4C–D and S3A), suggesting that their reformation was impaired due to stalling of recycling vesicle membranes at the stage of clathrin-coated intermediates. These changes were similar to those previously described upon disruption of SJ1 or of endophilin (Cremona et al., 1999; Hayashi et al., 2008; Milosevic et al., 2011; Schuske et al., 2003; Verstreken et al., 2003). Additionally, as at synapses where SJ1 function had been disrupted by genetic KO or peptide and antibody microinjection (Cremona et al., 1999; Gad et al., 2000), a prominent accumulation of a dense matrix (most likely actin) was observed. At some synapses, this accumulation correlated with clumping of synaptic vesicles in tight aggregates, suggesting pathological changes (Figure. S3D).

Delayed endocytosis in presynaptic nerve terminals

The accumulation of CCVs at mutant synapses suggests a predominant post-endocytic trafficking defect. However, using pHluorin-based assays of endocytosis we previously found evidence that loss of synaptojanin also results in endocytic defects (Mani et al., 2007). Thus, we assessed a potential defect of endocytosis in SJ1RQ-KI synapses using such assays.

In SJ1RQ-KI cortical neurons, the time constant of endocytic recovery following a 10 Hz stimulus for 5 s (50 AP) was approximately 2.5-fold slower (12.6 ± 1.3 s) than in WT (5.2 ± 0.3 s). The recovery in SJ1RQ-KI neurons was even slower after stronger stimulation (300AP, 10 Hz) (WT: 7.2 ± 0.5 s vs. SJ1RQ-KI: 22.3 ± 4.5 s) (Figure. 5A–B). Given sufficient time, however, the signal recovered in both cases, suggesting a kinetic delay, rather than a complete block of endocytosis, in SJ1RQ-KI neurons. No defect in exocytosis was observed, as inferred by analyzing the rising phase of the vGluT1-pHluorin signal during stimulation with 300 action potentials in the presence of bafilomycin (Figure. 5E). This drug, by blocking the acidification of endocytic vesicles, makes the signal of vGluT1-pHluorin blind to endocytosis. The kinetics of exocytosis in this stimulus regime likely reflects many steps, including release probability and the resupply of docked vesicles. We therefore also examined the fraction of the total nerve terminal pool of vGluT1-pHluorin (as measured by alkalinization of the vesicle lumen) that underwent exocytosis in response to a single action potential, which was also normal in SJ1RQ-KI neurons (Figure. 5F–G). By comparing the vGluT1-pHluorin signal with and without 0.5 μM bafilomycin during stimulation, we additionally determined the rate of endocytosis during electrical stimulation (Kim and Ryan, 2009) and found that such rate was the same in WT and SJ1RQ-KI neurons (Figure. 5C–D). This finding is consistent with previous results indicating that Sac domain of SJ1 is not required for endocytosis during stimulation (Mani et al., 2007). We conclude that there was a slower poststimulus endocytic reinternalization of synaptic vesicles proteins in SJ1RQ-KI synapses.

Figure 5. Synaptic vesicle endocytosis after electrical stimulation is slowed in SJ1RQ-KI neurons.

(A) Representative normalized traces of vGluT1-pHluorin in cortical neurons stimulated with 50 or 300 AP (10 Hz) indicate slower endocytosis in SJ1RQ-KI compared to WT.

(B) Endocytosis time constants after stimulation. Mean time constants ± SEM (sec): WT (50 AP) 5.2±0.3, SJ1RQ-KI (50 action potentials, AP) 12.6±1.3, WT (300 AP) 7.2±0.5, SJ1RQ-KI (300 AP) 22.3±4.5. n=18 cells per condition and genotype, one data point for the 300 AP stimulus in the SJ1RQ-KI (τ= 85 s) was excluded from the graphic (for clarity) but included in the mean value and statistical significance calculation.

(C) Endocytosis during electrical activity in SJ1RQ-KI neurons is similar to WT. Average difference in vGluT1-pHluorin signal before and after bafilomycin treatment at each time point during 300 AP-stimulation was plotted to represent ongoing endocytosis. All vGluT1-pHluorin values are normalized to the total pool determined from neutralization with NH4Cl. n=13–14 per genotype.

(D) Endocytic rate during 300 AP (10 Hz) is not significantly different in WT and SJ1RQ-KI neurons. Mean fraction of total vGluT1-pHluorin (%NH4Cl) endocytosed per second: WT 0.07±0.008 and SJ1RQ-KI 0.06±0.009. n=15 cells per genotype.

(E) Exocytic time constants do not differ in SJ1RQ-KI and WT, and were determined from the rising phase of vGluT1-pHluorin signal in bafilomycin-treated neurons stimulated with 300 AP. Mean exocytic time constants (sec): WT 14.1±2.0 and SJ1RQ-KI 16.9±1.8. n=15 cells per genotype.

(F) Representative vGluT1-pHluorin traces of WT and SJ1RQ-KI stimulated with a single AP reveal a similar exocytic response (% of total vGluT1-pHluorin pool).

(G) Average exocytic response to a single AP normalized to the total vGluT1-pHluorin pool. Mean response (% NH4Cl): WT 1.3±0.2 and SJ1RQ-KI 1.0±0.2. n=5–7 cells per genotype.

The box and whisker plot shows the median (line), 25th–75th percentile (box), and min-max (whisker). Error bars are SEM. **** P<0.00001.

Structural changes in a subset of DAergic nerve terminals in the dorsal striatum

H&E staining of the brains of 2-month old SJ1RQ-KI mice did not reveal gross alterations in brain structure (Figure. S4A). Likewise, immunostaining for GFAP and Iba1, markers of astrocytes and microglia cells respectively, did not demonstrate increased gliosis, a sign of neurodegeneration, in the brains of 8-month old SJ1RQ-KI mice (Figure. S4B). Thus, the neurological manifestation of SJ1RQ-KI mice are not the result of generalized neurodegenerative changes.

We next focused on the DAergic nigrostriatal pathway, which is specifically impaired in PD. Brain sections were immunostained for two different markers of DAergic neurons: tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a cytosolic protein, and the plasma membrane dopamine transporter (DAT). No obvious difference relative to controls was observed in the number or shape of cell bodies positive for TH in either the ventral tegmental area (VTA) or the substantial nigra (SN) regions of SJ1RQ-KI midbrain (Figure. S5A–C). In the striatum, i.e. the target territory of these neurons, a reticular pattern of DAT and TH immunoreactivity was observed, reflecting the dense network of DAergic axons. This reticular pattern was the same in WT and SJ1RQ-KI brains. However, additional sparse, large (several μm2), abnormal clusters of both DAT and TH were observed in SJ1RQ-KI striata (Figure. 6A). Importantly, these clusters were only observed in the dorsal part of striatum, which receives the DAergic input from the SN for motor function (nigrostriatal pathway), but not in ventral part of striatum, which receives input from the VTA for reward function (mesolimbic pathway) (Figure. 6A–C and S5D). This histological phenotype was not observed until one month after birth, suggesting this is due to an age-dependent early-onset dystrophic change, but not developmental change (Figure. 6D).

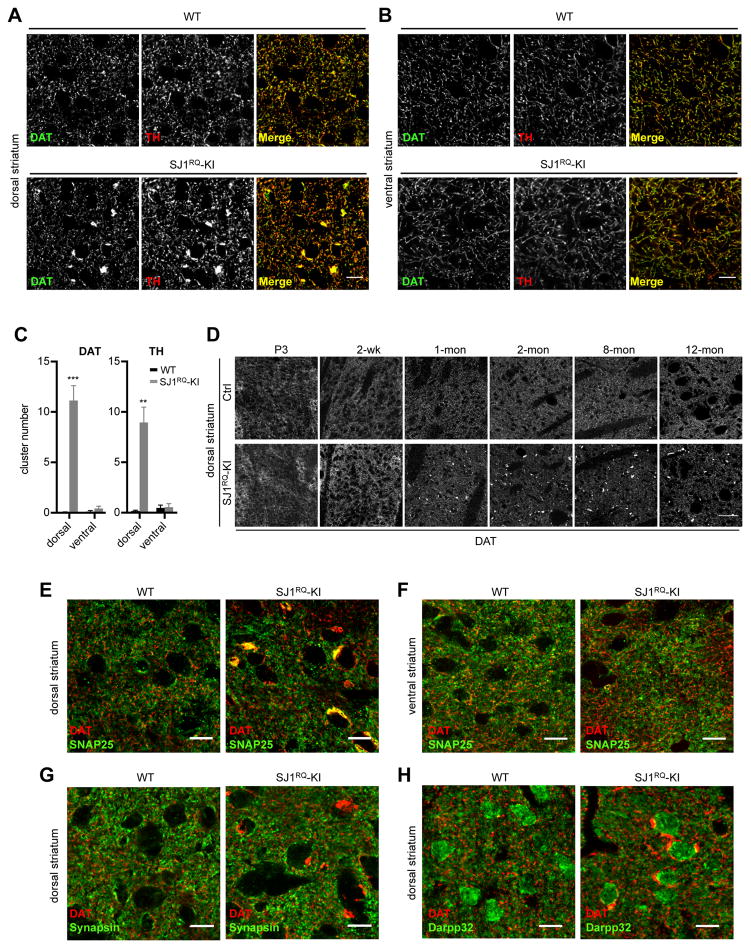

Figure 6. Dystrophic changes of DAergic axons in dorsal striatum of SJ1RQ-KI mice.

(A–B) Double immunofluorescence for the dopamine transporter (DAT, green) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, red), two markers of DAergic axons, in dorsal (A) and ventral (B) striatum derived from 8-month old WT and SJ1RQ-KI mice. Focal accumulations of these two proteins are present selectively in dorsal part of striatum in SJ1RQ-KI brain. Scale bar: 10μm

(C) Quantification of the results shown in A and B. The number of large DAT and TH immunoreactive clusters (>5 μm2) in 200×200 μm regions of interest (ROIs) was quantified. 5 random ROIs in the dorsal and ventral striatum were used for each mouse. (DAT: dorsal n=7, ventral n=6. TH: dorsal n=5, ventral n=4). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

(D) Representative images of DAT immunofluorescence in dorsal striatum of WT and SJ1RQ-KI brains at different ages (P3: postnatal day 3). Note that the clusters are not present until one month after birth. Scale bar: 50μm

(E–F) Double immunofluorescence staining of the dorsal (E) and ventral (F) striatum of WT and SJ1RQ-KI mice for DAT and for the plasma membrane protein, SNAP25. The selective accumulation of this ubiquitous neuronal plasma membrane SNARE protein at sites which are also positive for DAT positive clusters reveals a selective abnormality of DAergic nigrostriatal axons. Scale bar: 10μm

(G) Double immunofluorescence for DAT and for synapsin (synaptic vesicle marker) in the dorsal striatum of control and SJ1RQ-KI brains. Scale bar: 10μm

(H) Double immunofluorescence staining of the dorsal striatum for DAT and for DARPP32, a cytosolic marker of striatal medium spiny neurons, demonstrating that clusters of DAT-positive immunoreactivity are often observed close to the soma of such neurons. Scale bar: 10μm

See also Figure S4–S6 for additional data.

The DAT and TH positive clusters represented abnormal axons, as confirmed by double staining for DAT (the only DAT positive processes in the striatum are axons) and also for SNAP25, a neuronal plasma membrane SNARE protein present in axons (Garcia et al., 1995) (Figure. 6E). SNAP25 clusters not only precisely colocalized with DAT, but like DAT clusters were selectively present in the dorsal striatum and absent in the ventral striatum and other brain regions (e.g. cortex and cerebellum) (Figure. 6F and S6A–B). No obvious changes were observed for synaptic vesicles markers (synapsin, synaptophysin) (Takamori et al., 2006) (Figure. 6G and S6C). Double immunofluorescence for DAT and either DARPP32, a cytosolic marker of medium spiny neurons (MSNs) of the striatum (Hemmings and Greengard, 1986) (Figure. 6H), or MAP2 (a general marker of dendrites) (De Camilli et al., 1984) (Figure. S6D) showed no change of MSNs. However, this analysis revealed that the majority of DAT positive clusters were present near the soma of MSNs (Figure. 6H).

To explore the ultrastructure of clusters of immunoreactivity for markers of DAergic neurons, ultrathin frozen sections of the dorsal striatum of WT and SJ1RQ-KI mice were processed by immunogold electron microscopy using either rabbit anti-TH antibody, or a control rabbit antibody. Immunogold labeling for TH was selectively localized on a subset of thin neuronal processes (DAergic axons) in both WT and SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striatum (Figure. 7A). Importantly, additional large accumulations of anti-TH immunogold labeling, but not of control immunogold labeling, was specifically observed on large multi-layered membrane structures (onion-like) that were only present in SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striatum (Figure. 7B). The very sparse distribution of these structures in individual sections was consistent with the sparse spacing of clusters of DAT and TH immunofluorescence. Similar large onion-like membrane structures in proximity of the cell bodies of striatal neurons were also observed in SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striatum using conventional electron microscopy (Figure. 7C).

Figure 7. Ultrastructural analysis of the accumulations of markers of DAergic axons in SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striata.

(A) Anti-TH immunogold (15nm gold particles) labeling of ultrathin frozen sections of WT and SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striata. Immunogold particles were detected in a subset of neuronal processes in the striata of both genotypes, indicating specific labeling for DAergic axons.

(B) Immunogold labeling of ultrathin frozen sections of SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striata with anti-TH or control (anti-GFP) rabbit antibodies. Gold labeling of an onion-like multilayered membrane structure is observed with the anti-TH antibodies (right), while a multilayered membrane structure indicated by white arrows (left) is not labeled by control antibodies.

(C) Two examples of multilayered membrane structures visualized by conventional EM in the dorsal striatum of SJ1RQ-KI mice. CB = cell bodies of medium spiny neurons.

(D) Multilayered membrane structures (outlined in yellow) present in a 100×100×5μm volume of WT and SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striata as assessed by SBEM analysis. 3D rendering of the outer surface of these structures is shown against a micrograph of the last image of the SBEM series.

(E) Large clusters of DAT immunoreactivity present in a 100×100×5μm volume of WT and SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striata as visualized by 3D reconstruction of confocal Z-stack images. Note the similar overall abundance of large DAT-positive structures (E) and multilayered membrane structures observed in D.

The abundance of these membrane structures at EM analysis was further assessed by serial block-face scanning EM (SBEM), which allowed analysis of a large 3D volume of the dorsal striatum (100×100×22.5 μm). In such a volume we identified 8 such “onion-like” structures, which is consistent with the range of the clusters of TH and DAT immunoreactivity observed in a similar volumes analyzed at lower resolution by immunofluorescence. Equal volumes (100×100×5 μm) of WT and SJ1RQ-KI dorsal striata analyzed by SBEM or immunofluorescence are shown in Figure 7D and E. As seen by immunofluorescence of these clusters, these membrane structures were observed to be close to the cell bodies by the volume EM method of SBEM (Figure. S7, Movie S6).

DISCUSSION

We have generated KI mice homozygous for the SJ1 EOP mutation (SJ1R->Q) and found that they phenocopy neurological manifestations of patients: early onset motor coordination defects (defining features of PD) and epileptic seizures. Thus, SJ1RQ -KI mice represent a good model system to study molecular mechanisms underling neurological dysfunctions in patients with this mutation, also with potential implications for the understanding of other forms of EOP.

A role of the Sac domain in clathrin uncoating

Light and electron microscopic analysis of synapses of SJ1RQ-KI mice revealed the occurrence of a very robust accumulation of CCVs at synapses, with an accompanying reduction in the number of synaptic vesicles. This finding was unexpected, as the similar accumulation observed at synapses of neurons that completely lack SJ1 had been attributed to impaired PI(4,5)P2 loss due to dephosphorylation at the 5 position (Cremona et al., 1999) (synaptojanin does not dephosphorylate PI(4,5)P2 at the 4 position unless PI(4,5)P2 has been first dephosphorylated at the 5 position). PI4P, i.e. the product of the PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase activity of SJ1 and the main substrate for the phosphatase activity of the Sac domain (Guo et al., 1999; Nemoto et al., 2001), is not known to have a major role in the interaction between the endocytic clathrin adaptors and the membrane. Based on our previous demonstration that purified SJ1R->Q has no PI4P phosphatase activity but has normal PI(4,5)P2 phosphatase activity in vitro (Krebs et al., 2013), an indirect effect of the mutation on the 5-phosphatase activity seems unlikely, although one cannot exclude a potential cross-talk between the two domains in living cells. Likewise, it is unlikely that the Sac mutation may impact targeting of SJ1 to nerve terminals (see (Dong et al., 2015) for a potential role of the Sac domain in the synaptic targeting of SJ1), as SJ1R>Q was strikingly accumulated in nerve terminals along with other endocytic factors.

Potential explanations for the unexpected accumulation of CCVs in nerve terminals of SJ1RQ-KI mice will have to be explored in future studies. They may include a previously unappreciated role of PI4P in anchoring endocytic adaptors to the membrane, or a role in such anchoring of PI3P and PI(3,5)P2, two phosphoinositides that can be dephosphorylated (albeit less efficiently) by the Sac domain of SJ1 (Guo et al., 1999; Nemoto et al., 2001). While there is no evidence for PI(3,5)P2 at presynaptic endocytic sites, PI3P generation by Type II PI 3-kinases should be considered, as these kinases, so far poorly characterized in the nervous system, associate with clathrin coated pits (Nakatsu et al., 2010; Posor et al., 2013).

A qualitative survey of synapses of SJ1RQ-KI mice suggested that the accumulation of clathrin coated intermediates was not very different from the accumulation previously observed in neurons where SJ1 is not expressed (KO neurons) (Cremona et al., 1999; Hayashi et al., 2008) or not properly localized (neurons that lack all three endophilins) (Milosevic et al., 2011). Since the SJ1R->Q mutation produces a phenotype at the organismal level (EOP), that is much less severe than the absence of SJ1 (early death), there may be key functions of SJ1 beyond its role in endocytic clathrin coat dynamics.

A link between EOP and clathrin uncoating

The finding that both loss-of-function mutations in auxilin and a partial loss-of-function mutation in SJ1 result in EOP strongly supports a partnership of the two proteins in synaptic physiology and a role of abnormal endocytic clathrin coat dynamics in at least a subset of EOP patients. SJ1 promotes the dissociation of the endocytic clathrin adaptors that link the clathrin lattice to the bilayer (Cremona et al., 1999). Auxilin is a cofactor of HSC70, the triple AAA ATPase required for the disassembly of the clathrin lattice (Eisenberg and Greene, 2007; Fotin et al., 2004). As a consequence of the action of SJ1, disassembled clathrin triskelia on the newly formed vesicles are no longer anchored to the membrane via the clathrin adaptors and disperse in the cytosol. In the absence of SJ1 function, triskelia may linger around the coat still bound to the bilayer (possibly undergoing futile cycle of assembly-disassembly). Conversely, in the absence of auxilin, clathrin coats and ectopically assembled clathrin cages do not disassemble, as confirmed by the electron microscopic analysis of auxilin KO synapses (Yim et al., 2010). A plausible scenario is that the product(s) of the 5-phosphatase activity of SJ1 may help to recruit auxilin, as auxilin contains lipid binding modules: a C2 domain and a catalytically inactive PTEN phosphatase domain (Guan et al., 2010). The Sac domain activity would then promote the release of auxilin for its reuse in other cycles of uncoating. The very strong clustering of auxilin at nerve terminals of SJ1RQ-KI synapses is consistent with this possibility, although other scenarios can be considered.

Global versus specific defects in axon terminals of SJ1RQ-KI mice

Immunofluorescence and EM studies of SJ1RQ-KI neurons in cultures and in situ, as well as functional studies of synapses in neuronal cultures (pHluorin-based assays), revealed generalized defects in synaptic vesicle recycling. These defects may account for the occurrence of seizures in mutant mice and patients, as the abnormal accumulation of endocytic proteins at synapses appeared to be more prominent at inhibitory than at excitatory synapses, likely producing an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. Epilepsy is often observed in mice harboring loss-of-function mutations in endocytic proteins that function at synapses, including, besides SJ1 (Cremona et al., 1999) and the endophilins (Milosevic et al., 2011), amphiphysins (Di Paolo et al., 2002), dynamin 1 (Boumil et al., 2010), syndapin 1 (Koch et al., 2011) and AP180 (Koo et al., 2015). A greater vulnerability to endocytic defects of inhibitory synapses is probably due to their tonic firing pattern, which makes them more dependent upon the efficient reformation of synaptic vesicle pool (Luthi et al., 2001).

A key question is why, in view of this generalized phenotype, the neurological manifestations of patients with the SJ1R->Q mutation lead to Parkinsonism. We did not see an obvious loss of DAergic neurons in the SN of aged SJ1RQ-KI mice. However, we observed specific structural defects in a small subset of striatal DAergic nerve terminals, and selectively in the dorsal striatum. The dorsal striatum is the target of the nigrostriatal DAergic pathway, i.e. the pathway specifically impaired in PD. As DAergic neurons of this system have different structural and functional features relative to DAergic neurons of the VTA (e.g. different axonal arborization size and pacemaking mechanism) (Aransay et al., 2015; Khaliq and Bean, 2010; Matsuda et al., 2009), a different susceptibility of these neurons to the mutation is plausible. At the light microscopic level, these structures were represented by focal and robust clusters of immunoreactivity for DAT, a plasma membrane protein of DAergic nerve terminals, and for the axonal plasma membrane SNARE SNAP25. At the electron microscope level, these abnormal nerve terminals were characterized by onion-like accumulations of plasma membrane. Concerning the implications of these abnormal nerve terminals for Parkinsonism, we note that at the light microscopic level, these structures are strikingly reminiscent of those observed in the dorsal striatum of heterozygous KO mice for the transcription factor engrailed 1, another PD model (Nordstrom et al., 2015). At the electron microscopy level, similar structures were observed at presynaptic terminals of α-synuclein transgenic mouse brains and shown to result from a massive invagination of the plasma membrane (Boassa et al., 2013). Mechanisms underlying the formation of such structures, such as the possibility that they may result from impaired endocytosis, and reasons for their occurrence only in a subset of nerve terminals, remain to be investigated. However, their exclusive occurrence in nerve terminals of nigrostriatal neurons in our mouse model reveals a selective functional lability of such neurons.

A link between several protein implicated in PD and endocytic traffic

In addition to SJ1 and auxilin, several other proteins implicated by genetic studies in PD are linked, directly or indirectly, to the endocytic pathway and to clathrin-dependent budding in particular. The E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin interacts with endophilin and ubiquitinates both endophilin and SJ1 (Cao et al., 2014; Trempe et al., 2009). As we have shown previously, parkin levels are increased in endophilin KO brains (Cao et al., 2014). We have now found that a similar up-regulation of parkin occurs in SJ1RQ-KI brains, strongly linking the function of parkin to that of both endophilin and synaptojanin. Other links between PD proteins and the endocytic pathway include the following: 1) LRRK2 has been implicated in endocytic and endosomal function (Beilina et al., 2014; MacLeod et al., 2013; Schreij et al., 2015; Steger et al., 2016), and most interestingly in the context of the present study, it regulates endophilin and SJ1 by phosphorylation (Arranz et al., 2015; Islam et al., 2016; Matta et al., 2012; Soukup et al., 2016). 2) Loss of α-synuclein leads to increased level of endophilin (Westphal and Chandra, 2013). 3) Autosomal dominant late-onset PD mutations were identified in another cofactor of HSC70, the protein RME8/DNAJC13 (PARK21), which is involved in clathrin-dependent budding from endosomes (Vilarino-Guell et al., 2014). 4) Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) studies have linked several endocytic proteins to Parkinsonism. These include cyclin-G-associated kinase (GAK/DNAJC26), a ubiquitously expressed homolog of auxilin (Nalls et al., 2014), and Hip1R, a protein that couples clathrin to actin (Liu et al., 2011). Most importantly, they also include Sac2/INPP5F (Nalls et al., 2014), a protein that functions in the early endocytic pathway and contains a Sac domain with the same catalytic activities as the Sac domain of SJ1 (Hsu et al., 2015; Nakatsu et al., 2015). Together, these findings suggest a strong link between dynsfunction in early endocytic traffic and PD. An explanation for these findings is still missing. The sequestration of endocytic coats in assembled complexes may impair endocytic flux of membrane cargo from the plasma membrane or affect other clathrin-dependent sorting reactions, such as those that occur on endosomes or at the trans-Golgi network. Alternatively, these assembled complexes may stress protein quality control systems. Competition for chaperones by protein aggregates leading to impaired endocytosis have also been reported (Yu et al., 2014). Some characteristic(s) of nigrostriatal neurons may make them more vulnerable to these changes.

In conclusion, our present study provides new evidence 1) for a link between disruption of endocytic membrane traffic and EOP and 2) for a functional relationship between SJ1 and other PD genes. At the mechanistic level, it reveals an unexpected role of the Sac domain of SJ1 in clathrin uncoating and thus a functional partnership between the Sac domain and the 5-phsophatase domain of SJ1 in this process. Further investigation of the selective impact of the SJ1R->Q mutation on DAergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway using the SJ1RQ-KI mouse model will likely provide new insight into pathogenic mechanisms in EOP.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Lead Contact Pietro De Camilli (pietro.decamilli yale.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

SJ1RQ knock-in (KI) mice with an arginine to glutamine substitution at position 259 of mouse Synj1 (CGG>CAG, corresponding to the human R258Q EOP mutation), were custom generated by the Gene Targeting & Transgenic Facility of HHMI Janelia Research Campus. The knock-in construct was produced using recombineering techniques (Liu et al., 2003). A 7,881bp genomic DNA fragment containing exons 4–6 of the Synj1 gene was retrieved from BAC clone RP23-2A19 and transferred to a vector containing a DTA negative selection marker. The R259Q mutation was generated by PCR that changed the codon CGG to CAG. The PCR fragment was cloned to a frt-PGKNeo-frt cassette which was inserted 258 bp down stream of Exon 5. The mutant-frt-RGCNeo-frt cassette was then recombined to the vector containing the Synj1 genomic DNA fragment so that the mutation was flanked by homologous arms of 4.7 kb and 3.4 kb respectively. The targeting vector was electroporated into G1 ES cells which were derived from a F1 hybrid blastocyst of 129S6 x C57BL/6J. G418 resistant ES colonies were isolated and screened by nested PCR using primers outside the construct paired with primers inside the frt-PGKNwo-frt cassette. The 5′ arm screening primers were Synj1 sc 5F1 (5′-tacaggttgatcatgctagca-3′) and PGK scr R1 (5′-tggatgtggaatgtgtgcga-3′). The nested PCR primers were Synj1 sc 5F2 (5′– gccaaggttcagagctatgt-3′) and PGK scr R2 (5′-taaagcgcatgctccagact -3′). The 3′ arm screening primers were frt scr F1 (5′-ttctgaggcggaaagaacca --3′) and Synj1 scr 3R1, (5′-atgcatggctgacaacacga 3′). The nested primers were frt scr F2 (5′-ggaacttcatcagtcaggta -3′) and Synj1 scr 3R2 (5′-tagtcagcaagactccctgt -3′). The ES clones with both arms positive were identified for the generation of chimeric mice. To this aim, ES cells were aggregated with 8-cell embryos of CD-1 strain. Correct targeting was further confirmed by homozygosity test in the progenies. The neo cassette was removed by mating the chimeras with R26FLP (Jax Stock number: 003946) homozygous females that had been backcrossed to C57bl/6j for 11 generations. F1 pups were genotyped by PCR using primers flanking the frt site, and the mutation was confirmed by sequencing. The primer set for the frt site was Synj1 gt 5F (5′-gatagctacctggagtttgc -3′) and Synj1 gt 3R (5′-gctgggttatagcctgaaac -3′) that generated PCR products of 328 bp for the wild type allele and 396 bp for the mutant allele. The primers for mutation sequencing were Synj1 mut seq F (5′-gtcgttagtgacctaatgcag -3′) and Synj1 mut seq R (5′-gcaaactccaggtagctatc -3′).

Mice were maintained on the C57BL6/129 hybrid genetic background. Mice heterozygous for the mutation were mated to generate homozygous mice (KI/KI) and littermate that were used as controls (either WT or heterozygous). No obvious differences were observed between heterozygous and WT mice. All mice were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. All research and animal care procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Primary cortical neuron cultures

Primary cortical neurons were cultured in Neurobasal/B27 serum-free medium, and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

METHOD DETAILS

Motor coordination tests

2–12 months old SJ1RQ-KI and littermate control mice (n=7) were used for the following motor behavior tests. Experiments were carried out with randomly chosen littermates of the same sex. Both males and females were used. All behavioral studies were carried out during the light period. Mice were habituated to the test room for at least 1 hr before each test. The same sets of animals were used for different tests starting with the less aversive test. In order to recover, mice were given al least one day between tests. All behavior apparatuses were cleaned between each trial with 70% ethanol.

Hindlimb clasping test

Mice were held by their tail for 30 s and the frequency and duration of hindlimb clasping was scored.

Rotarod test

Mice were placed on a rod and the rod was rotated at 4 rpm with an acceleration to 40 rpm within 5 mins. The “time to fall” was measured 4 times at 10 mins intervals and the average “time to fall” was determined for each mouse.

Balance beam test

Mice were placed on one end of a narrow beam (20mm/12mm width) suspended 20 cm above a soft mattress, and their movement towards the other end was recorded by video camera. The number of missteps (paw faults, or slips) during the trip was scored.

Grip test

This test, which is a measure of muscle strength, was conducted by placing mice on top of a 0.5 cm wire mesh, inverting the mesh and keeping it suspended at 1 meter above the cage for 2 mins. Mice which let go, will fall into the cage filled with soft bedding material. The time to fall (in seconds) was determined for each mouse.

Footprint test

The fore and hind paws of mice were dipped in non-toxic water-color paint (red and blue), so that the mice leave a trail of footprints as they walk or run along a corridor to a goal box. Stride length, sway length, and stance length were analyzed.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies used in this study were generated in our lab: rabbit anti-SJ1, mouse anti-amphiphysin1, rabbit anti-auxilin, mouse anti-clathrin heavy chain (TD1), mouse anti-alpha-adaptin (AP6), rabbit anti-intersectin, rabbit anti-Eps15, mouse anti-dynamin3 (5H5), rabbit anti-Epsin1, rabbit anti-SNAP25, rabbit anti-synapsin, rabbit anti-synaptophysin. Antibodies obtained from commercial sources were as follows: mouse anti-pan-dynamin, mouse anti-α-synuclein, mouse anti-EEA1, mouse anti-MAP2, and mouse anti-GM130 (BD biosciences); mouse anti-amphiphysin2, rabbit anti-clathrin light chain, rabbit-anti-VPS35, rabbit anti-HIP1R, mouse anti-PSD95, guinea pig anti-vGluT1, mouse anti-vGluT2, rabbit anti-TH (AB152), rabbit anti-RME8 and rat anti-DAT (MAB369) (Millipore); mouse anti-parkin and rabbit anti-EIF4G1 (Cell Signaling Technology); rabbit anti-vGAT, rabbit anti-endophilin1, mouse anti-rab5, mouse anti-rab3, mouse anti-VAMP2, and mouse anti-synaptotagmin (Synaptic Systems); mouse anti-AP180 (Sigma); mouse anti-HSC70 (Thermo ABR); rabbit anti-LC3 (PM036,MBL); rabbit-anti-LRRK2 (Epitomics); mouse anti-actin (C4, MP Biomedicals); rabbit anti-Cav1.3 (Alomone Labs); rat anti-LAMP1 (ID4, DSHB); rabbit anti-Iba1(Wako); rabbit anti-nWASP (ECM biosciences); rabbit anti-GFAP (DAKO); rabbit anti-Ube3a (Bethyl). The following antibodies were kind gifts: mouse anti-syntaxin1 (HPC1, Colin Barnstable, Penn State university); rabbit anti-Sac2 (Yuxin Mao, Cornell University, NY); mouse anti-GAD65 (GAD6, David Gottlieb, Washington University, Saint Louis, MO); rabbit anti-DARPP32 (Angus Nairn, Yale University, New Haven, CT); rabbit anti-GAK (Lois Greene, NIH).

Immunoblotting

Post-nuclear supernatant of brain tissue was obtained by homogenization of mouse brain in buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM EDTA supplemented with protease inhibitors and subsequent centrifugation at 700g for 10 mins. Protein concentration was determined by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit. SDS-PAGE and western blotting were performed by standard procedures. Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent and quantified by densitometry using Fiji software. At least three independent pairs of samples were used for quantification.

Primary cortical neuron culture and staining

Cultures of cortical neurons were prepared from P0 to P2 neonatal mouse brains by previously described methods (Ferguson et al., 2007) and used at DIV7 to DIV23. Briefly, cortical tissue was dissected out, placed in ice-cold HBSS, and minced with a scalpel until pieces were <1 mm3. Tissue was then digested for 30 min in an activated enzyme solution containing papain (20 U/ml) and DNase (20 μg/ml) at 37°C, followed by gentle trituration. Cell suspensions were plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips to a density of 12,000–20,000 cells/cm2. The day after plating, the medium was exchanged to Neurobasal/B27 serum-free medium, and cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde [freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde (PFA)], 0.1M sodium phosphate pH 7.2 and 4% sucrose, rinsed with 50mM NH4Cl, blocked and permeablized with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), PBS and 0.1% triton X-100. Primary and secondary antibody incubations were subsequently performed in the same buffer. Alexa-488, 594 and 647 conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. After washing, samples were mounted on slides with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). To silence neuronal activity, cultures were treated with tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1μM) for 16 hrs before the fixation. Samples were observed by either a Perkin Elmer Ultraview spinning disk confocal microscope equipped with 60x CFI PlanApo VC objective or a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 63× plano Apo objective.

Brain histology and immunofluorescence

Mice were anesthetized with a Ketamin/xylazine anesthetic cocktail injection, perfused transcardially with ice-cold 4% formaldehyde (see above) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and the brains were kept in the same fixative overnight at 4 °C. Brains were then transferred to increasing concentrations of sucrose (10%, 20% and 30% (w/v)] in PBS, embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek) and frozen in liquid nitrogene-cooled isopentane. Coronal or sagittal (15–30μm thickness) sections were cut with a cryostat and mounted on Superfrost™ Ultra Plus Adhesion slides (Thermo Scientific). Sections were then blocked with a solution containing 3% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, PBS and 0.1% Triton-X100 for 1hr at room temperature, incubated with primary antibodies (diluted in the same buffer) overnight at 4°C, washed, incubated with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1hr at room temperature and finally mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI and sealed with nail polish. Images were acquired with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 63× plano Apo (NA 1.4) oil-immersion objective lens or a 20× (NA 0.8) objective. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed by standard procedures.

For stereological analysis of TH-positive dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, 30μm coronal sections were incubated with 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity and subsequently incubated with blocking buffer for 1hr at room temperature. Next, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-TH primary antibodies (1:100). The sections were then washed with PBS and incubated with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, USA) for 1 hr at room temperature followed by incubation with the Avidin/Biotin complex (ABC) reagent for 30 min at room temperature (Vector Laboratories, USA). Finally, immunoreactivity was revealed by incubation with diaminobenzidine (DAB). Stereological analysis was performed using the optical fractionator probe in the Stereo Investigator software (MBF Bioscience, USA). Every 4th section of a pool of about 40 sections per animal were counted. The VTA and SN regions were outlined based on the Allen mouse brain atlas and counts were performed using a 20x objective. The parameters used include a counting frame size of 60 × 60 μm, a sampling site of 120 × 120 μm, a dissector height of 18 μm, 2 μm guard zones and the Schmitz-Hof’s second estimated coefficient error less than 0.15.

Quantification of immunoreactivity clustering

The endocytic protein clustering quantification was done using Fiji software as follows. The same threshold intensity was applied to all images and then the random region of interest was manually selected. A mask was used to quantify puncta bigger than 0.1 μm2. After this processing, average fluorescence puncta intensity in control and SJ1RQ-KI neurons/brain sections were measured. Co-localization analysis was carried out by measuring the Pearson’s correlation coefficient using the Fiji colocalization plug-in Coloc2. For DAT and TH positive clustering in striatum, automated counting of the clusters was performed using the Fiji plugin “Analyze particles” for a total of 20–35 random sampling sites of 200 μm × 200 μm in size from four to seven animals per genotype. Clusters were thresholded for a minimum size of 5 μm2, so we ensured that abnormal clusters were counted without counting normal DAT and TH positive axonal terminals.

Electron microscopy

All EM reagents were from EMS, Hatfield, PA, unless noted otherwise. 4–8 months old WT and SJ1RQ-KI mice were anesthetized as above for light microscopy and then fixed by perfusion with ice-cold 2% formaldehyde (see above) and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. Approximately 1mm × 1mm pieces of brain tissue were incubated in the same fixative for additional 2 hrs at room temperature, post-fixed (1 hr) in 2% OsO4, 1.5% K4Fe(CN)6 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer, stained (1hr) with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate, dehydrated in gradually increasing concentration of EtoH, and embedded in Embed 812. Ultrathin sections, about 60 nm thick, were cut with Leica ultramicrotome and observed in a Philips CM10 microscope at 80 kV. Images were taken with a Morada 1 k × 1 k CCD camera (Olympus). For immunogold labeling, WT and SJ1RQ-KI mice were perfused with 4% formaldehyde and 0.125% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Dorsal and ventral striata were dissected and embedded in 1% gelatin in 0.1M phosphate buffer. Samples were processed for ultracryomicrotomy as described in (Slot and Geuze, 2007). Ultrathin cryosections were labeled with anti-Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) antibody and protein A coupled to 15nm gold (Aurion). EM sections were observed in a Philips CM10 electron microscope equipped with a Morada 2k × 2k charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Olympus).

For SBEM, mice were perfused with the primary fixative (2.5% glutaradehyde + 2% PFA + 2 mM Ca2+ in 0.15 M NaCacodylate buffer, pH7.4) for 5 min at 35 °C. Brain tissue was cut into 80–100 μm coronal sections in ice-cold phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with a vibrotome, and sections were further fixed for additional 2–3 hrs in the perfusion fixative on ice. Next, tissue sections were processed through the following incubations: 2% OsO4 + 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in 0.15 M Nacacodylate buffer for 1 hr on ice; TCH (thiocarbohydrazide) (Ted Pella) in water for 20 min at room temperature; wash with ddH2O; 2% OsO4 for another 30 min at room temperature; 2% aqueous uranyl acetate overnight at 4 °C. En bloc Walton’s lead aspartate staining was then performed (30 min at 60 °C). Tissue sections were dehydrated in ethanol (graded increases from 20% to 100%) on ice then transferred to ice-cold propylene oxide and raised to room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, they were infiltrated with hard Epon resin that was formulated as follows: Epon 812: 24 g, DDSA: 9 g, NMA: 15 g, DMP-30 2%. Finally, tissue sections were mounted with fresh resin between liquid release agent-coated glass slides and kept for 48 hrs at 60°C.

In order to accurately select the dorsal striatum for SBEM imaging, heavy-metal stained tissue slices (see above) were imaged in a Zeiss Versa 510 X-ray microscope. 2D projection images revealed the anatomical landmarks within each tissue slice. Based on these images, a small piece of dorsal striatum (<1mm × 1mm) was cut out of a slice and mounted with cyanoacrylate glue onto an Aclar sheet. The specimen was sectioned until tissue was exposed and mounted on an SEM rivet using silver epoxy (Ted Pella) with the exposed tissue in contact with the silver epoxy. The specimen was coated with gold-palladium in a sputter coater and SBEM imaging was performed on a Zeiss Merlin SEM equipped with a Gatan 3View system. Sections were 50 nm thick and pixel size was 4.15 nm. Image stacks were aligned using cross correlation in IMOD (Kremer et al., 1996).

pHluorin assays

Cortices were dissected from WT and SJ1RQ KI littermates at postnatal day 1 or 2, dissociated with trypsin, and plated on poly-ornithine-coated coverslips, and transfected with vGluT1-pHluorin as previously described (Ferguson et al., 2007). Imaging of vGluT1-pHluorin and electrical stimulation were performed at 37 °C according to published procedures (Armbruster et al., 2013) blinded to the genotype. Briefly, coverslips were mounted in a laminar flow perfusion chamber and perfused at 37 °C with Tyrode’s buffer containing (in mM) 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 50 HEPES (pH 7.4), 5 glucose, supplemented with 10 μM 6-cyano-7nitroquinoxalibe-2, 3-dione (CNQX), and 50 μM D,L-2-amino-5phosphonovaleric acid (APV) (both from Sigma) to inhibit post-synaptic responses. Alkalization of pHluorin-containing intracellular vesicles was achieved with a solution that had the same composition as Tyrode’s buffer except that it contained (in mM) 50 NH4Cl and 69 NaCl. To measure endocytosis during synaptic activity, neurons were incubated with 0.5 μM bafilomycin A (EMD Millipore, 19-148) diluted in Tyrode’s buffer ~30 seconds prior to the start of electrical stimulation. The rate of endocytosis during and after stimulation was determined as previously described (Mani et al., 2007). Exocytosis of vGluT1-pHluorin in response to single action potential stimulation was measured by averaging 4–6 stimulations in Tyrodes buffer containing 4 mM Ca2+. The responses are expressed as a percentage of the total vesicle pool as determined by the fluorescence obtained during perfusion of NH4Cl. During the course of these experiments two WT cells (not shown) showed single AP exocytosis with responses that were 3 times greater than the mean exocytosis response. As this mean exocytosis response was very similar to our previously reported values for rat hippocampal neurons (Kim and Ryan, 2013), the two outliers were excluded from the analysis. Graphing and statistical analysis were performed with OriginPro v8 and GraphPad Prism v6.0 for PC, respectively. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine the significance of the difference between two conditions.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data is presented as mean+/−SEM. For the data not specified, statistical significance was determined using student t tests and data with P values <0.05, <0.01 and <0.001 are indicated by asterisks *, ** and ***, respectively. For pHluorin assays, statistical significance was determined using Mann–Whitney U test, and data with P values <0.00001 are indicated by asterisks ****. Statistical parameters including the exact value of n, precision measures (mean ± SEM) and statistical significance are reported in the figure legends.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

No applicable

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

No applicable

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| rabbit polyclonal anti-SJ1 | De Camilli lab | Gesualdo |

| mouse monoclonal anti-amphiphysin1 | De Camilli lab | N/A |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-auxilin | De Camilli lab | Babe |

| mouse monoclonal anti-clathrin heavy chain | De Camilli lab | TD1 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-alpha-adaptin | De Camilli lab | AP-6 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-intersectin | De Camilli lab | N/A |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Eps15 | De Camilli lab | EH-1 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-dynamin3 | De Camilli lab | 5H5 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Epsin1 | De Camilli lab | P94 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-SNAP25 | De Camilli lab | MC21 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-synapsin | De Camilli lab | G246 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-synaptophysin | De Camilli lab | G95 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-pan-dynamin (Clone 41) | BD biosciences | Cat#610246; RRID: AB_3976413 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-α-synuclein | BD biosciences | Cat# 610786; RRID: AB_398107 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-EEA1 | BD biosciences | Cat# 610457; RRID:AB_397830 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-MAP2 | BD biosciences | Cat# 610460 RRID:AB_397833 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-GM130 | BD biosciences | Cat# 610822; RRID:AB_398141 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-TH | Millipore | Cat# AB152; RRID: AB_390204 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-clathrin light chain | Millipore | Cat# AB9884; RRID: AB_11211734 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-VPS35 | Millipore | Cat# ABT48; RRID:AB_10806774 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-HIP1R | Millipore | Cat# AB9882; RRID:AB_992784 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-RME8 | Millipore | Cat# ABN1657 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-PSD95 | Millipore | Cat# MAB1596; RRID:AB_2092365 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-vGluT2 | Millipore | Cat# MAB5504; RRID:AB_2187552 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-amphiphysin2 | Millipore | Cat# 05-449; RRID:AB_309738 |

| guinea pig polyclonal anti-vGluT1 | Millipore | Cat# AB5905; RRID:AB_2301751 |

| rat monoclonal anti-DAT | Millipore | Cat# MAB369; RRID:AB_2190413 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-parkin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4211; RRID:AB_2159920 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-EIF4G1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2858S; RRID:AB_2095745 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-vGAT | Synaptic System | Cat# 131 002; RRID:AB_887871 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-endophilin1 | Synaptic System | Cat# 159 002; RRID:AB_887757 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-rab5 | Synaptic Systems | Cat# 108 011 RRID:AB_887773 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-rab3 | Synaptic Systems | Cat# 107 011 RRID:AB_887768 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-VAMP2 | Synaptic Systems | Cat# 104 211 RRID:AB_887811 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-synaptotagmin | Synaptic Systems | Cat# 105 011 RRID:AB_887832 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-AP180 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# A4825; RRID:AB_258203 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-HSC70 | Thermo ABR | Cat# MA3-014; RRID:AB_325462 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3 | MBL | Cat# PM036 RRID:AB_2274121 |

| rabbit monoclonal anti-LRRK2 | Abcam (Epitomics) | Cat# 3514-1; RRID:AB_10643781 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-actin (Clone C4) | MP Biomedicals | Cat# 08691001; RRID:AB_2335127 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Cav1.3 | Alomone Labs | Cat# ACC-005; RRID:AB_2039775 |

| rat monoclonal anti-LAMP1 | DSHB | Cat# 1d4b; RRID:AB_2134500 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Iba1 | Wako | Cat# 019-19741; RRID:AB_839504 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-nWASP | ECM biosciences | Cat# WP2101; RRID:AB_715260 |

| rabbit monoclonal anti-GFAP | DAKO | Cat# Z0334; RRID:AB_10013382 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Ube3a | Bethyl | Cat# A300-351A RRID:AB_185563 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-syntaxin1 | Colin Barnstable, Pennsylvania State University Barnstable et al, 1985 (PMID 3896407) Email: cjb30@psu.edu |

HPC1 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Sac2 | Yuxin Mao, Cornell University Hsu et al, 2015 (PMID 25869669) Email: ym253@cornell.edu |

PMID: 25869669 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-GAD65 | David Gottlieb, Washington University, Saint Louis Chang et al, 1988 (PMID 3385490) Email: gottlied@pcg.wustl.edu |

GAD6 |

| rabbit anti-DARPP32 | Angus Nairn, Yale University Email: angus.nairn@yale.edu |

N/A |

| rabbit anti-GAK | Lois Greene, NIH Yim et al, 2010 (PMID 20160091) Email: greenel@helix.nih.gov |

PMID: 20160091 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Tetrodotoxin (TTX) | TOCRIS | Cat#1078 |

| 6-cyano-7nitroquinoxalibe-2, 3-dione (CNQX) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# C239 |

| D,L-2-amino-5phosphonovaleric acid (APV) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# A5282 |

| Bafilomycin A | EMD Millipore | Cat# 19-148 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Deposited Data | ||

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: SJ1RQ-KI mice (R259Q, CGG>CAG) | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Sequence-Based Reagents | ||

| SJ1RQ-KI genotyping primers: Fwd: 5′-gatagctacctggagtttgc -3′ and Rev: 5′-gctgggttatagcctgaaac -3′ | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| SJ1RQ-KI sequencing primers: Fwd: 5′-gtcgttagtgacctaatgcag -3′ and Rev: 5′-gcaaactccaggtagctatc -3′ | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Fiji | ImageJ | https://fiji.sc/ |

| Graphpad Prism | Graphpad Software | http://www.graphpad.com/ |

| 3DMOD | IMOD | http://bio3d.colorado.edu/imod/ |

| Stereo Investigator | MBF Bioscience | http://www.mbfbioscience.com/stereo-investigator |

| Other | ||

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sreeganga Chandra, Shawn Ferguson, Nii Addy and Yiying Cai for discussion, Frank Wilson, Louise Lucast, Lijuan Liu, Alvaro Duque and Lucy Saidenberg for technical assistance, Sheng Ding, Tian Xu and Sreeganga Chandra for sharing animal behavioral test instruments, Caroline Zeiss for mouse pathology service and discussion, Caiying Guo (Janelia Research Campus mouse facility) for the generation of knock-in mouse. This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (NS36251 and DA18343 to P.D.C., NS036942 to T.A.R.), the Michael J. Fox Foundation (#11353 to P.D.C. and M.C.), NIH GM103412 (M.H.E.) for support of the National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research, from The Branfman Family Foundation (M.H.E and D.B.) and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation to M.C..

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to some aspects of experimental design and data analysis. M.C. and P.D.C. designed the study and analyzed results. Conventional EM and immunogold EM were performed by Y.W and H.W. respectively. G.A. and T.A.R. generated and analyzed the pHluorin data. A.J.M. performed some experiments with neuronal cultures. E.A.B., D.B., and M.H.E. performed SBEM. All other experiments were performed by M.C.. M.C. and P.D.C. prepared the manuscript, which was reviewed by all coauthors.

References

- Aransay A, Rodriguez-Lopez C, Garcia-Amado M, Clasca F, Prensa L. Long-range projection neurons of the mouse ventral tegmental area: a single-cell axon tracing analysis. Frontiers in neuroanatomy. 2015;9:59. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster M, Messa M, Ferguson SM, De Camilli P, Ryan TA. Dynamin phosphorylation controls optimization of endocytosis for brief action potential bursts. eLife. 2013;2:e00845. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arranz AM, Delbroek L, Van Kolen K, Guimaraes MR, Mandemakers W, Daneels G, Matta S, Calafate S, Shaban H, Baatsen P, et al. LRRK2 functions in synaptic vesicle endocytosis through a kinase-dependent mechanism. Journal of cell science. 2015;128:541–552. doi: 10.1242/jcs.158196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilina A, Rudenko IN, Kaganovich A, Civiero L, Chau H, Kalia SK, Kalia LV, Lobbestael E, Chia R, Ndukwe K, et al. Unbiased screen for interactors of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 supports a common pathway for sporadic and familial Parkinson disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:2626–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318306111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boassa D, Berlanga ML, Yang MA, Terada M, Hu J, Bushong EA, Hwang M, Masliah E, George JM, Ellisman MH. Mapping the subcellular distribution of alpha-synuclein in neurons using genetically encoded probes for correlated light and electron microscopy: implications for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:2605–2615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2898-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumil RM, Letts VA, Roberts MC, Lenz C, Mahaffey CL, Zhang ZW, Moser T, Frankel WN. A missense mutation in a highly conserved alternate exon of dynamin-1 causes epilepsy in fitful mice. PLoS genetics. 2010:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Milosevic I, Giovedi S, De Camilli P. Upregulation of Parkin in endophilin mutant mice. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:16544–16549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1710-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona O, Di Paolo G, Wenk MR, Luthi A, Kim WT, Takei K, Daniell L, Nemoto Y, Shears SB, Flavell RA, et al. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 1999;99:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Camilli P, Miller PE, Navone F, Theurkauf WE, Vallee RB. Distribution of microtubule-associated protein 2 in the nervous system of the rat studied by immunofluorescence. Neuroscience. 1984;11:817–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Heuvel E, Bell AW, Ramjaun AR, Wong K, Sossin WS, McPherson PS. Identification of the major synaptojanin-binding proteins in brain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8710–8716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G, Sankaranarayanan S, Wenk MR, Daniell L, Perucco E, Caldarone BJ, Flavell R, Picciotto MR, Ryan TA, Cremona O, et al. Decreased synaptic vesicle recycling efficiency and cognitive deficits in amphiphysin 1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;33:789–804. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman DK, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Altered synaptic development and active zone spacing in endocytosis mutants. Current biology: CB. 2006;16:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Gou Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Bai J. Synaptojanin cooperates in vivo with endophilin through an unexpected mechanism. eLife. 2015:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouet V, Lesage S. Synaptojanin 1 mutation in Parkinson’s disease brings further insight into the neuropathological mechanisms. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:289728. doi: 10.1155/2014/289728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyment DA, Smith AC, Humphreys P, Schwartzentruber J, Beaulieu CL, Bulman DE, Majewski J, Woulfe J, Michaud J, et al. Consortium FC. Homozygous nonsense mutation in SYNJ1 associated with intractable epilepsy and tau pathology. Neurobiology of aging. 2015;36:1222, e1221–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardson S, Cinnamon Y, Ta-Shma A, Shaag A, Yim YI, Zenvirt S, Jalas C, Lesage S, Brice A, Taraboulos A, et al. A deleterious mutation in DNAJC6 encoding the neuronal-specific clathrin-uncoating co-chaperone auxilin, is associated with juvenile parkinsonism. PloS one. 2012;7:e36458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Multiple roles of auxilin and hsc70 in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Traffic. 2007;8:640–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsad K, Ringstad N, Takei K, Floyd SR, Rose K, De Camilli P. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. The Journal of cell biology. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Brasnjo G, Hayashi M, Wolfel M, Collesi C, Giovedi S, Raimondi A, Gong LW, Ariel P, Paradise S, et al. A selective activity-dependent requirement for dynamin 1 in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Science. 2007;316:570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1140621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotin A, Cheng Y, Grigorieff N, Walz T, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T. Structure of an auxilin-bound clathrin coat and its implications for the mechanism of uncoating. Nature. 2004;432:649–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gad H, Ringstad N, Low P, Kjaerulff O, Gustafsson J, Wenk M, Di Paolo G, Nemoto Y, Crun J, Ellisman MH, et al. Fission and uncoating of synaptic clathrin-coated vesicles are perturbed by disruption of interactions with the SH3 domain of endophilin. Neuron. 2000;27:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia EP, McPherson PS, Chilcote TJ, Takei K, De Camilli P. rbSec1A and B colocalize with syntaxin 1 and SNAP-25 throughout the axon, but are not in a stable complex with syntaxin. The Journal of cell biology. 1995;129:105–120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan R, Dai H, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T. Structure of the PTEN-like region of auxilin, a detector of clathrin-coated vesicle budding. Structure. 2010;18:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Stolz LE, Lemrow SM, York JD. SAC1-like domains of yeast SAC1, INP52, and INP53 and of human synaptojanin encode polyphosphoinositide phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12990–12995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardies K, Cai Y, Jardel C, Jansen AC, Cao M, May P, Djemie T, Hachon Le Camus C, Keymolen K, Deconinck T, et al. Loss of SYNJ1 dual phosphatase activity leads to early onset refractory seizures and progressive neurological decline. Brain. 2016;139:2420–2430. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TW, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Jorgensen EM. Mutations in synaptojanin disrupt synaptic vesicle recycling. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;150:589–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Raimondi A, O’Toole E, Paradise S, Collesi C, Cremona O, Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Cell- and stimulus-dependent heterogeneity of synaptic vesicle endocytic recycling mechanisms revealed by studies of dynamin 1-null neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:2175–2180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712171105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC, Jr, Greengard P. DARPP-32, a dopamine-regulated phosphoprotein. Progress in brain research. 1986;69:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu F, Hu F, Mao Y. Spatiotemporal control of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate by Sac2 regulates endocytic recycling. The Journal of cell biology. 2015;209:97–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201408027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]