Abstract

Acute bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) are essentially lung inflammatory disorders. Various plant extracts and their constituents showed therapeutic effects on several animal models of lung inflammation. These include coumarins, flavonoids, phenolics, iridoids, monoterpenes, diterpenes and triterpenoids. Some of them exerted inhibitory action mainly by inhibiting the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and nuclear transcription factor-κB activation. Especially, many flavonoid derivatives distinctly showed effectiveness on lung inflammation. In this review, the experimental data for plant extracts and their constituents showing therapeutic effectiveness on animal models of lung inflammation are summarized.

Keywords: Medicinal plant, Lung inflammation, COPD, Constituent, Flavonoid

INTRODUCTION

Lung inflammatory disorders comprise airway diseases including acute bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) such as chronic bronchitis, chronic asthma and emphysema. Particularly, COPD is the 5th leading cause of death worldwide. They are essentially inflammatory diseases. Several classes of drugs such as antitussives, mucolytics and bronchodilators are clinically used to treat the symptom, resulting in a relatively well-controlled condition. However, chronic diseases (COPD) are hard to control with the currently available drugs, which only relieve the symptoms of bronchitis. They do not affect or reverse the pathological progress of COPD. Thus, many pharmaceutical firms are trying to develop new drugs that target the pathological courses of COPD, eventually leading to a complete cure.

Among the drug candidates, leukotriene antagonists and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors show some promising results (Reid and Pham, 2012). However, success of low molecular weight drugs remains low since COPD is a very complex disease in etiology and in disease processes as described below. Up to the present, critical target molecules that mainly affect the disease process of COPD have not been found. In this context, plant extracts having complex and diverse chemicals may be favorable. Several plant-based anti-inflammatory drugs are used frequently, especially for acute as well as chronic bronchitis. Examples are the extracts of Hedera helix (Guo et al., 2006), Echinacea purpurea (Sharma et al., 2006) and Pelargonium sidoides (Agbabiaka et al., 2008; Matthys and Funk, 2008). These contain various classes of constituents that demonstrate complex action mechanisms on the above diseases. From many plants, a variety of constituents have been isolated and tested for their potential in treating these disorders. Despite various findings concerning the inhibitory actions of lung inflammation by herbal products, few available systematic reviews are focused on the therapeutic effects on animal models of lung inflammatory disorders. Therefore, in this review, plants that have therapeutic effectiveness on the animal models of lung inflammation are summarized. Plant constituents possessing therapeutic effects on lung inflammation are also discussed. However, this review is not comprehensive. Only findings of English literature are summarized. Anti-asthmatic effects by the plant products are not included.

COPD: ETIOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS

The pathological factors affecting COPD are diverse and intricately linked. In the deteriorating progress of COPD, various inflammatory mediators are released from epithelial cells and infiltrated inflammatory cells in the lungs, including neutrophils, macrophages and T lymphocytes. It is important that proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6 and chemokines including IL-8 activate and attract the circulating cells in the pathological process. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) has been reported to cause airway fibrosis, leading to airway destruction. Several approaches for blocking these cytokines or their receptors have been developed for clinical trial against COPD. Among them, IL-1β and IL-18, key molecules of inflammasome, are suggested as potential targets along with other inflammasome components (Rovina et al., 2009; Zhang, 2011).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are also critical for provoking COPD. Tobacco smoke contains high concentrations of oxidants and induces a variety of free radicals including ROS. Oxidative stress by excess generation of ROS amplifies the inflammatory responses and develops the pathological stage of COPD. Therefore, several molecules linked to oxidative stress, such as nuclear erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), NADPH oxidase, myeloperoxidase and superoxide dismutase may be considered targets for COPD therapy. Also, an imbalance between proteases and anti-proteases leads to alveolar wall destruction. Especially, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and neutrophil elastase are intricately regulated in COPD pathology. Several reports indicate that the activation and/or elevated expression of matrix metalloproteinases such as MMP-2, -9 and -12 are closely related to the development of COPD (Churg et al., 2012). Recently sirtuins were demonstrated to be deeply involved in COPD. The level of sirtuin 1 expression is reduced in the lungs of COPD patients. The activation of sirtuin 1 and 6 has been shown to have protective effects against COPD (Chun, 2015) and sirtuin activators may be proposed as candidates for COPD treatment.

Additionally, eicosanoids and nitric oxide (NO) have been shown to be involved. Leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels in the exhaled breath condensate of patients with COPD are higher than in healthy subjects (Muntuschi et al., 2003). LTB4 is a potent neutrophil chemoattractant and its concentration in sputum is also increased in COPD patients (Corhay et al., 2009). To reduce LTB4 levels, antagonists of LTB4 receptors and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors have been developed for the treatment of COPD. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is widely up-regulated in the airways and peripheral lungs of COPD patients (Hesslinger et al., 2009). NO synthesized by iNOS and its oxidant peroxynitrite cause oxidative stress in the lungs. In the animal model, iNOS inhibition by a selective inhibitor was shown to partially improve pulmonary vessel remodeling and functional destruction by smoke-induced emphysema (Seimetz et al., 2011).

Recent investigations suggested that interrupting signal transduction pathways may alleviate COPD progress. Various kinases participate in regulating the expression of inflammatory genes and transcription factors related to COPD. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) are proposed as promising representative targets for the development of selective inhibitors. The activation of p38 MAPK induces inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-8 and MMP in various inflammatory cells, leading to the exacerbation of COPD symptoms. The inhibition of p38 MAPK showed efficacy in a six month clinical trial in COPD patients with ≤2% blood eosinophils (Marks-Konczalik et al., 2015). PI3K-mediated signaling in macrophages and neutrophils is involved in inflammation and immune responses and the activity is up-regulated in the lungs of COPD. It was found that blocking certain isoforms of PI3K reduced pulmonary neutrophilia in a murine smoke model (Doukas et al., 2009). Several PI3K inhibitors have been developed as candidates for COPD therapy so far. In addition, inhibitors targeting transcription factor, nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB), which is involved in the encoding of many inflammatory genes and relevant kinases such as IκB kinase have been also investigated (Schuliga, 2015). However, because some approaches targeting these signaling pathways may have significant problems induced by selectivity, specificity and side effects linked to other pathways, more detailed studies will be needed to determine the best target in treating COPD.

CURRENTLY DEVELOPING DRUG CANDIDATES FOR COPD

Since COPD is characterized by chronic progression and the complexity of parameters priming the disease, previous therapies for COPD have been limited to the use of drugs such as inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids, which only improve the symptoms. This means that further detailed clinical trials for many other targets related to COPD are required for the development of new therapy. Recently, COPD management has been focused on anti-inflammatory therapy because COPD is basically an inflammatory disease.

Roflumilast, a PDE4 inhibitor, showed anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting neutrophil functions and the activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in COPD patients with chronic bronchitis (Pinner et al., 2012). Clinical trials with new PDE4 inhibitors such as RPL554 and CHF6001, which have lower side effects and better efficacy, are ongoing for the development of more potent agents in COPD therapy (Franciosi et al., 2013; Moretto et al., 2015).

Among inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, TNF-α and IL-8 are primarily under development as targets for COPD treatment. TNF-α plays a role in attracting neutrophils and exists in highly variable concentrations in the blood or lungs of patients with COPD. Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab, antibodies targeting TNF-α or TNF receptor (TNFR), have been developed to alleviate the symptoms of COPD pathogenesis. However, some studies reported adverse effects of infliximab in patients with COPD (Dentener et al., 2008). Etanercept showed no beneficial effects (Aaron et al., 2013). One of the reasons is assumed to be related to the TNF-α concentration of COPD patients and the stage of COPD pathogenesis. Blocking chemokines such as IL-8/C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) with neutralizing antibody reduced neutrophil chemotactic activity in stable COPD patients (Mahler et al., 2004). However, the redundancy in the chemokine network caused the therapeutic effect to be partial. Clinical application with several antagonists of C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2, CXCL8 receptor) such as navarixin (SCH 527123, MK-7123) and AZD-5069 was carried out in CODP patients but showed no effective results (Norman, 2013; Rennard et al., 2015). Danirixin (GSK1325756), an oral CXCR2 antagonist is in phase II development for COPD.

Besides antibodies against TNF-α and IL-8, variable antibodies targeting other cytokines have been developed so far. IL-1β and IL-5 are potential targets for COPD therapy. Anti-bodies against IL-1 (Canakinumab and MEDI8986) and IL-5 (Benralizumab and Mepolizumab) were developed, but their efficacy and side effects have to be determined through additional clinical trials, which are currently ongoing. Treatment with antibody blocking IL-5 receptors such as benralizumab, which have been previously developed for asthma treatment, was also attempted in certain patients with COPD and eosinophilia (Brightling et al., 2014) and a clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety is currently underway in patients with COPD. In particular, active IL-1β is produced by nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, so the inflammasome implicated in COPD is emerging as a new COPD target (Hosseinian et al., 2015). But it is unclear whether the inflammasome directly participates in COPD pathogenesis. Further detailed investigation to confirm the contribution of inflammasome to COPD pathology will be needed.

A current potential target for COPD treatment is p38 MAPK, which is shown to be related to the control of the expression of multiple inflammatory mediators. Recently, some p38 MAPK inhibitors developed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis were challenged in clinical trials for COPD (Watz et al., 2014; Norman, 2015). The development of oral p38 MAPK inhibitors such as acumapimod is ongoing for clinical treatment of COPD. Inhaled p38 MAPK inhibitors, PF-03715455 and RV-568, are in Phase I and Phase II clinical trials, respectively (Norman, 2015). However, the development of PH-797804 and losmapimod was terminated for COPD treatment because they showed no improved effects compared to roflumilast, a PDE4 inhibitor. Another kinase, PI3K, which is upregulated in the lungs of COPD patients, can also be a potential target for CODP therapy (To et al., 2010). Although TG100-115, PI3Kγ and -δ inhibitor, was proven to be effective in the mouse smoke-induced lung inflammation model (Doukas et al., 2009), the clinical development has been discontinued at present. Recent study suggested that targeting PI3Kδ was beneficial for the treatment of respiratory diseases (Sriskantharajah et al., 2013). GSK2269557, an inhaled PI3Kδ inhibitor, is currently undergoing clinical trial for COPD.

MMP-9, MMP-12 and neutrophil elastase play important roles in the breakdown of collagen and elastin fibers in emphysema patients. Several protease inhibitors targeting these proteases have been developed but discontinued for various reasons such as efficacy problems and side effects in clinical trials. To date, various drug candidates that block the signaling pathway related to the induction mechanisms of COPD pathogenesis have been developed. They showed effectiveness in several animal models. But most human trials have been stopped due to their low efficacy and major side effects. Thus, continual efforts to define new target molecules and to find agents that interrupt various signaling processes are needed. As an alternative to these efforts, plants and plant products have been studied with the hope of finding new and effective agents to treat these inflammatory lung disorders.

ANIMAL MODELS OF LUNG INFLAMMATION

There are several animal models of lung inflammation used for establishing the therapeutic effects of target compounds. For acute lung inflammation, the most widely used model is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury (inflammation) model (Rojas et al., 2005; Matute-Bello et al., 2008). Mice used are ICR, BALB/c, C57BL/6, etc. LPS is either administered via the intratracheal or intranasal route. Sometimes, rats are used and LPS is intratracheally administered in this case. Rarely, sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas and chlorine gas are used as inflammagens instead of LPS. From the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), the cells are counted. Infiltrated neutrophils and macrophages are major cells. The lung tissues show typical inflammatory conditions such as alveolar wall hyperplasia and many infiltrated inflammatory cells can be observed in histological samples. In LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI) model, proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines as well as oxidative stress contribute to provoking inflammatory responses. Thus, anti-oxidative treatments such as Nrf2 pathway activation attenuate lung inflammatory responses (Kim et al., 2010). Proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines are frequently detected in the BALF. Generally, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 are elevated. In our study, IL-6 and IL-8 levels are increased in the BALF 16 h after LPS treatment by the nasal route in ICR mice (Lim et al., 2013). In these animal models, the NF-κB activation pathway plays an essential role in provoking lung inflammation. The MAPK pathway is also involved.

In animal models of chronic lung inflammation, cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation may be used. Cigarette smoke exposure to mice and rats for several days or weeks produces COPD-similar changes in the affected lung tissues (Wright et al., 2008). Inflammatory cells are recruited to lung tissues. Elevated numbers of goblet cells producing mucins are also observed in some cases using Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Similar changes are also obtained in an animal model of LPS/elastase-treated mice (Ganesan et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012). Elastase administered to the lung for weeks sometimes destroys the alveolar layer to produce large emphysema-like lesions. However, this change may be confined to several strains of mice. In our experiment with ICR mice, this change was hardly observed, although elevated levels of infiltrated inflammatory cells in the BALF could be detected (data not shown). The similar finding was also demonstrated that cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammatory responses were varied on mice strains (Morris et al., 2008). To date, animal models mimicking human COPD have not been adequately established. The relevance of animal models and human COPD is not satisfactory. Generally, agents showing activity in animal models of chronic lung inflammation do not show high effectiveness in clinical trials. Thus, new animal models need to be established for successful development of new drugs against COPD.

THE INHIBITION OF PLANT EXTRACTS AGAINST IN VIVO ANIMAL MODELS OF LUNG INFLAMMATION

In this review, findings using the septic shock model are not mentioned since intraperitoneal or intravenous injection of endotoxin (LPS) provokes systemic inflammation leading to the cytokine storm instead of local airway inflammation in the lung. LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI) produces local lung inflammation. Some potential effects of herbal products on ALI were summarized previously (Favarin et al., 2013). Recently, effects of dozens of plant-derived compounds on lung inflammatory diseases including asthma and COPD models are also described (Santana et al., 2016).

Many medicinal plants have shown regulatory effects on lung inflammation at doses of approximately 100–300 mg/kg as summarized in Table 1. On the other hand, Gleditsia sinensis, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Lonicera japonica, Taraxacum officinale extracts and the petroleum ether fraction of Viola yedoensis showed potent inhibitory activity by oral administration against LPS-induced lung inflammation at low doses (Xie et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012b; Kao et al., 2015). They showed significant inhibition at doses as low as 3 mg/kg. Gleditsia sinensis is known to possess anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory activity (Dai et al., 2002; Ha et al., 2008). It contains various triterpenoids as major components (Lim et al., 2005). Many triterpenoids were previously found to possess anti-inflammatory activity (Kim et al., 1999). All this information suggests that G. sinensis has potential for treating lung inflammatory diseases.

Table 1.

Inhibition of the animal models of lung inflammation by various plant extracts

| Plants | Extracts | Doses (mg/kg)a) | Inflammagen usedb) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthopanax senticosus | c) | 20 (i.v.) | LPS (i.t.) | Fei et al. (2014) |

| Aconitum tanguticum | Alkaloid fraction | 30–60 | LPS (rat) | Wu et al. (2014a) |

| Alisma orientale Juzepzuk | 80% ethanol | 300–1,200 | LPS | Han et al. (2013) |

| Angelica decursiva | 70% ethanol | 400 | LPS | Lim et al. (2014) |

| Antrodia camphorata | Methanol | 25–100 | LPS | Huang et al. (2014a) |

| Alstonia scholaris | Alkaloid fraction | 7–30 | LPS (i.t.) (rat) | Zhao et al. (2016) |

| Azadirachta indica | Water | 100/day | Cigarette smoke | Koul et al. (2012) |

| Callicarpa japonica Thunb. | Methanol | 15–30/day | Cigarette smoke | Lee et al. (2015d) |

| Canarium lyi C.D. Dai & Yakovlev | Methanol | 30/day | LPS | Hong et al. (2015b) |

| Chrysanthemum indicum | Supercritical CO2 extract | 40–120/day | LPS (i.t.) | Wu et al. (2014b) |

| Cnidium monnieri | Water | 50–200/day | Cigarette smoke extract/LPS (i.t.) | Kwak and Lim (2014) |

| Eleusine indica | 400 (i.p.) | LPS | De Melo et al. (2005) | |

| Euterpe oleracea Mart. | 50% ethanol | 300/day | Cigarette smoke | Moura et al. (2012) |

| Galla chinensis | 100/day | Cigarette smoke | Lee et al. (2015a) | |

| Ginkgo biloba | Egb761 | 0.01–1 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Huang et al. (2013) |

| Gleditsia sinensis | Water | 3.3–10/day | LPS | Choi et al. (2012) |

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | Flavonoid fraction | 3–30 | LPS (i.t.) | Xie et al. (2009) |

| Houttuynia cordata | 70% ethanol | 400 | LPS | Lee et al. (2015b) |

| Juglans regia L. kernel | Methanol | 50–100/day | Cigarette smoke (rat) | Qamar and Sultana (2011) |

| Lonicera japonica flos | 50% ethanol | 0.4–40 | LPS (i.t.) | Kao et al. (2015) |

| Lysimachia clethroides Duby | Methanol | 20–100 (i.p.) | LPS | Shim et al. (2013) |

| Mikania glomerata Spreng and Mikania laevigata Schultz Bip. Ex Baker | 70% ethanol | 100 (s.c.) | Mineral coal dust (i.t.) (rat) | Freitas et al. (2008) |

| Morus alba | 70% ethanol | 200–400 | LPS | Lim et al. (2013) |

| Nigella sativa | Hydroethanolic extract | 80/day | Sulfur mustard (guinea-pigs) | Hossein et al. (2008) |

| Paeonia suffruticosa | Granule | 2,000 | LPS (i.t) (rat) | Fu et al. (2012) |

| Phellodendri cortex | Methanol | 100–400 | LPS (i.t.) | Mao et al. (2010) |

| Punica granatum | 0.9% NaCl | 200 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Bachoual et al. (2011) |

| Rabdosia japonica var. glaucocalyx | Flavonoid fraction | 6.4–25.6/day | LPS (i.t.) | Chu et al. (2014) |

| Schisandra chinensis Baillon | Water | 10–100 | LPS | Bae et al. (2012) |

| Schisandra chinensis Baillon | Aqueous ethanol | 1,000/day | Cigarette smoke-induced cough hypersensitivity (guinea pig) | Zhong et al. (2015) |

| Stemona tuberosa | Water | 50–200/day | Cigarette smoke | Lee et al. (2014) |

| Taraxacum officinale | Water | 2.5–10/day | LPS | Liu et al. (2010) |

| Taraxacum mongolicum hand.-Mazz | Water | 5,000–10,000 | LPS | Ma et al. (2015a) |

| Uncaria tomentosa | Water | Ozone | Cisneros et al. (2005) | |

| Viola yedoensis | Petroleum ether | 2–8 | LPS | Li et al. (2012b) |

| Formula: Dangkwisoo-san | Mixture | 100–1,000/day | LPS | Lyu et al. (2012) |

| Formula: Gingyo-san | Mixture | 1–2 | LPS (i.t.) | Yeh et al. (2007b) |

| Formula: Hochu-ekki-to (TJ-41) | Mixture | 1,000/day | LPS | Tajima et al. (2006) |

| Formula: Xia-Bai-San | Mixture | 1 | LPS (i.t.) | Yeh et al. (2006) |

| Formula: BP+LJ | Mixture | 100–400 | LPS (i.t.) (rat) | Ko et al. (2011) |

All extracts were orally administered unless otherwise stated.

Mice were used as experimental animals unless otherwise indicated. Administration route of inflammagens was intranasal. Intratracheal route (i.t.) was indicated. Cigarette smoke was administered by inhalation route.

Due to the insufficient information provided, space remained blank.

Lonicera japonica is a well-known anti-inflammatory agent (Lee et al., 1998). The entire plant including the leaves and flowers is widely used in traditional medicine as an anti-inflammatory agent especially for treating upper airway inflammatory diseases. L. japonica is an ingredient of many complex prescriptions for lung inflammatory disease in ancient literatures. It contains iridoids and flavonoids as major components, which show significant anti-inflammatory activity (Lee et al., 1995).

In addition, the alkaloid fractions of Aconitum tanguticum and Alstonia scholaris inhibited LPS-induced ALI in rats at low doses (Wu et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2016).

Ginkgo biloba leaves extract showed considerable inhibition of lung inflammation in LPS-induced ALI at low doses when they were administered intraperitoneally (Huang et al., 2013). G. biloba leaves extract has been used to enhance blood circulation, prevent neurodegeneration and enhance cognitive function. The anti-inflammatory action of G. biloba leaves is well known (Ilieva et al., 2004). G. biloba leaves also exert an anti-asthmatic effect (Babayigit et al., 2009). Thus, this medicinal plant material has the potential to treat lung-related inflammatory/allergic diseases. The major constituents are ginkgolides and flavonoids. Many flavonoid derivatives show inhibitory action on lung inflammation as described below.

Against the COPD model induced by cigarette smoke, several plant extracts such as Azadirachta indica, Callicarpa japonica, Cnidium monnieri, Euterpe oleracea, Galla chinensis, Juglans regia, Schisandra chinensis and Stemona tuberosa were found to inhibit inflammatory responses in the lung (Qamar and Sultana, 2011; Koul et al., 2012; Moura et al., 2012; Kwak and Lim, 2014; Lee et al., 2014, 2015a, 2015d; Zhong et al., 2015), suggesting their therapeutic potential in chronic lung inflammatory diseases. Particularly, S. chinensis has been widely used for lung disorders in traditional medicine in the East Asia region, and the findings above provide the scientific basis for this traditional use. This extract was found to inhibit acute as well as chronic inflammatory condition of lung inflammation. But no report is available establishing the activity of its constituents. The therapeutic potential of the major constituents such as schizandrin and gomisins remains to be discovered in the near future.

Hedera helix (ivy leaf, Guo et al., 2006), Echinacea purpurea (Sharma et al., 2006; Agbabiaka et al., 2008) and Pelargonium sidoides (Matthys and Funk, 2008) are frequently used for treating bronchitis in Asian and European countries. The extracts alleviate the symptoms of acute and chronic bronchitis such as sputum production and coughing. Ivy leaves extract has been prescribed for treating bronchitis under the name Prospan® (Ahngook Pharm., Seoul, Korea). Pelagonium sidoides ethanol extract under the name Umckamin syrup® (Han Wha Pharma Co., Seoul, Korea) is used for acute bronchitis. It is significant to note that ivy extract also showed some effectiveness against influenza A virus infection in mice when simultaneously administered with the antiviral drug, Tamiflu (Hong et al., 2015a). The therapeutic effectiveness of some herbal remedies in COPD patients has been summarized (Guo et al., 2006). In human clinical study, some ginseng products showed promising results in COPD patients (Gross et al., 2002). Recently, we have found that some ginseng products and ginsenosides clearly inhibited lung inflammatory responses in a mouse model of ALI (data not shown).

Sometimes, a combination of herbal plants gives more promising results. Several herbal mixtures were also demonstrated to possess inhibitory action on lung inflammation. Particularly, Xia-Bai-San demonstrated efficacy at the dose of 1 mg/kg against LPS-induced ALI (Yeh et al., 2006). Recently, a new formula, Synatura® (Ahngook Pharm., Seoul, Korea) containing ivy leaf and Coptis chinensis was developed for treating chronic bronchitis.

THE INHIBITION OF PLANT CONSTITUENTS AGAINST IN VIVO ANIMAL MODELS OF LUNG INFLAMMATION AND ACTION MECHANISMS

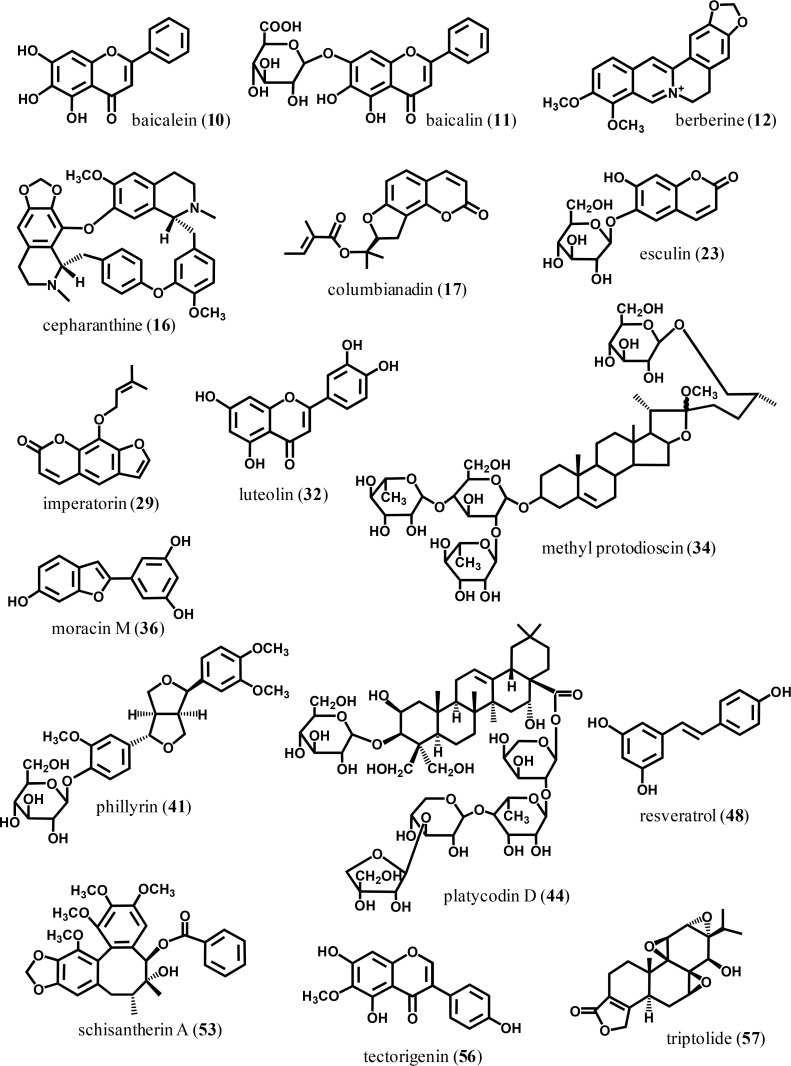

Resveratrol (stilbenoid, 48) (Fig. 1) was found to show strong inhibitory action against acute lung inflammation and the COPD model (Donnelly et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2014a). Resveratrol showed effectiveness through the reduction of proinflammatory cytokine and prostanoid generation. In one study, resveratrol was revealed to reduce the inflammatory responses in cigarette smoke-induced COPD mice by inhibiting NF-κB activation and the elevation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression (Liu et al., 2014a). The detailed anti-inflammatory action mechanisms of resveratrol, curcumin and glycyrrhetic acid are well summarized in the previous review paper (Sharafkhaneh et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of some selected plant constituents mentioned in this study.

Some phenolics also showed effectiveness against lung inflammation by oral administration. These include apocynin (8), caffeic acid derivative (13), ellagic acid (19), paeonol (39) and zingerone (59) (Table 2). Particularly, paeonol, a major ingredient from Paeonia suffruticosa, inhibited a mice model of COPD, cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation at 10 mg/kg/day (Liu et al., 2014b). This finding is well correlated with the inhibitory potential of P. suffruticosa extract against LPS-induced ALI in rats (Fu et al., 2012). Ellagic acid protected against lung damage induced by acid treatment (Cornélio Favarin et al., 2013). This compound was demonstrated to reduce IL-6 production along with the increase of anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, in BALF, but, no inhibition of NF-κB and activator protein-1 (AP-1) activation was observed. Similar pharmacological mechanisms were also found in zingerone (phenol) treatment for LPS-induced ALI (Xie et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Inhibition of the animal models of lung inflammation by plant constituents

| Constituent | Class | Plant origin | Doses (mg/kg)a) | Inflammagen usedb) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acteoside (1) | Phenylethanoid | Rehmannia glutinosa | 30–60 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Jing et al. (2015) |

| Afzelin (2), hyperoside (3), quercitrin (4) | Flavonoid | Houttuynia cordata | 100, 100, 100 | LPS | Lee et al. (2015b) |

| Alpinetin (5) | Flavonoid | Alpinia katsumadai | 50 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Huo et al. (2012) |

| Andrographolide (6) | Diterpene | Andrographis paniculata | 1/day (i.p.) | Cigarette smoke | Yang et al. (2013) |

| Apigenin-7-glucoside (7) | Flavonoid | c) | 2.5–10 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Li et al. (2015) |

| Apocynin (8) | Phenol | Picrorhiza kurroa | 0.002–0.2/ml | LPS (hamster) | Stolk et al. (1994) |

| Asperuloside (9) | Iridoid | 20–80 (i.p.) | LPS | Qiu et al. (2016) | |

| Baicalein (10) | Flavonoid | Scutellaria baicalensis | 20 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) (rat) | Tsai et al. (2014) |

| Baicalin (11) | Flavonoid | Scutellaria baicalensis | 25–100/day | Cigarette smoke | Li et al. (2012a) |

| Baicalin (11) | Flavonoid | Scutellaria baicalensis | 20 | LPS (i.t.) (rat) | Huang et al. (2008) |

| Berberine (12) | Alkaloid | 5–10/day (i.p.) | Cigarette smoke | Xu et al. (2015) | |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (13) | Phenol | Honey-bee propolis | 10 μmol/kg/day | Cigarette smoke (rabbit) | Sezer et al. (2007) |

| Cannabidiol (14) | Cannabinoid | Cannabis sativa | 20 | LPS | Ribeiro et al. (2012) |

| Carvacrol (15) | Monoterpene | Plectranthus amboinicus | 20–80 (i.p.) | LPS | Feng and Jia (2014) |

| Cepharanthine (16) | Alkaloid | Stephania cepharantha Hayata | 5 (i.p.) | LPS | Huang et al. (2014b) |

| Columbianadin (17) | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | 20–60 | LPS | Lim et al. (2014) |

| p-cymene (18) | Monoterpene | 25–100 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Xie et al. (2012) | |

| Ellagic Acid (19) | Phenol | 10 | Acid | Cornélio Favarin et al. (2013) | |

| Ergosterol (20) | Sterol | Scleroderma polyrhizum Pers. | 25–50 | LPS | Zhang et al. (2015) |

| Eriodictyol (21) | Flavonoid | Dracocephalum rupestre | 30/day | LPS | Zhu et al. (2015) |

| Esculentoside A (22) | Saponin | Phytolacca esculenta | 15–60 | LPS | Zhong et al. (2013a) |

| Esculin (23) | Coumarin | 20–40 | LPS (i.t.) | Tianzhu and Shumin (2015) | |

| Flavone (24), fisetin (25), tricetin (26) | Flavonoid | 22.2, 28.6, 30.2 | LPS (i.t.) | Geraets et al. (2009) | |

| Gossypol (27) | Sesquiterpene | 15 (i.p.) | LPS | Huo et al. (2013b) | |

| Hesperidin (28) | Flavonoid | 200 | LPS (i.t.) | Yeh et al. (2007a) | |

| Imperatorin (29) | Coumarin | 15–30 | LPS | Sun et al. (2012) | |

| Limonene (30) | Monoterpene | 25–75 (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Chi et al. (2013) | |

| Linalool (31) | Monoterpene | Aromatic plant | 25 (i.p.) | LPS | Huo et al. (2013a) |

| Linalool (31) | Monoterpene | Aromatic plant | 10–40 (i.p). | Cigarette smoke | Ma et al. (2015b) |

| Luteolin (32) | Flavonoid | Lonicera japonica | 70 μmol/kg (i.p.) | LPS (i.t.) | Lee et al. (2010) |

| Mangiferin (33) | Xanthone | Mangifera indica L. | 450–4,050/day | LPS | Wang et al. (2015) |

| Methyl protodioscin (34) | Steroidal saponin | Asparagus cochinchinensis | 30–60 | LPS | Lee et al. (2015c) |

| Mogroside V (35) | Triterpene saponin | Momordica grosvenori | 2.5–10 | LPS | Shi et al. (2014) |

| Moracin M (36) | 2-arylbenzofuran | Morus alba | 20–60 | LPS | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Morin (37) | Flavonoid | 20–40 | LPS | Tianzhu et al. (2014) | |

| Naringin (38) | Flavonoid | 20–80/day | Cigarette smoke (rat) | Nie et al. (2012) | |

| Paeonol (39) | Phenol | Paeonia suffruticosa | 10/day | Cigarette smoke | Liu et al. (2014b) |

| Patchouli alcohol (40) | Sesquiterpene | Pogostemon cablin | 10–40 (i.p.) | LPS | Yu et al. (2015) |

| Phillyrin (41) | Lignan | Forsythia suspensa | 10–20 | LPS | Zhong et al. (2013b) |

| Picroside Ii (42) | Iridoid | Picrorhiza scrophulariiflora | 0.5–1 (i.t.) | LPS (i.t.) | Noh et al. (2015) |

| Pinocembrin (43) | Flavonoid | Alpinia katsumadai | 20–50 (i.p.) | LPS | Soromou et al. (2012) |

| Platycodin D (44) | Triterpenoid saponin | Platycodon grandiflorum | 50–100 | LPS (i.t.) | Tao et al. (2015) |

| Prime-O-glucosylcimifugin (45) | Chromone | Saposhnikovia divaricata | 2.5–10 (i.p.) | LPS | Chen et al. (2013) |

| Protocatechuic acid (46) | Benzoic acid | 30 (i.p.) | LPS | Wei et al. (2012) | |

| Quercetin (47) | Flavonoid | 10/day | LPS/elastase | Ganesan et al. (2010) | |

| Quercetin (47) | Flavonoid | 25–30/day (i.p.) | Cigarette smoke (rat) | Yang et al. (2012) | |

| Resveratrol (48) | Stilbene | LPS | Donnelly et al. (2004) | ||

| Resveratrol (48) | Stilbene | 1–3/day | Cigarette smoke (3 days) | Liu et al. (2014a) | |

| Sakuranetin (49) | Flavonoid | Baccharis retusa | 20 (i.n.) | Elastase-induced emphysema | Taguchi et al. (2015) |

| Schaftoside (50), vitexin (51) | Flavonoid | Eleusine indica | 0.4, 0.4 (i.p.) | LPS | De Melo et al. (2005) |

| Shikonin (52) | Naphthoquinone | Lithospermum erythrorhizon | 12.5–50 | LPS (i.t.) | Bai et al. (2013) |

| Schisantherin A (53) | Lignan | Schisandra sphenanthera | 10–40 | LPS | Zhou et al. (2014) |

| Stevioside (54) | Diterpene | Stevia rebaudiana | 12.5–50 | LPS | Yingkun et al. (2013) |

| Taraxasterol (55) | Triterpene | Taraxacum officinale | 2.5–10 (i.p.) | LPS | San et al. (2014) |

| Tectorigenin (56) | Flavonoid | Belamcanda chinensis | 5–10 (i.v.) | LPS (i.t.) | Ma et al. (2014) |

| Triptolide (57) | Diterpene | Tripterygium wilfordii | 0.005–0.015 | LPS | Wei and Huang (2014) |

| Usnic acid (58) | Dibenzofuran | Lichen species | 25–100/day | LPS | Su et al. (2014) |

| Zingerone (59) | Phenol | 10–40 | LPS | Xie et al. (2014) |

All compounds were orally administered unless otherwise stated.

Mice were used as experimental animals unless otherwise indicated. Administration route of inflammagens was intranasal. Intratracheal route (i.t.) was indicated. Cigarette smoke was administered by inhalation route.

Constituents from commercial sources were purchased or could be isolated from various plant sources.

The benzoic acid derivative, protocatechuic acid (46), significantly inhibited LPS-induced ALI by inhibiting NF-κB activation via inhibiting IκBα degradation and the translocation of p65 to the nucleus (Wei et al., 2012). Limonene (monoterpene, 30) also inhibited LPS-induced ALI by the downregulation of MAPK and NF-κB activation (Chi et al., 2013). Linalool (31) demonstrated inhibitory activity in the cigarette smoke-induced COPD model by the same action mechanism of blocking NF-κB activation (Ma et al., 2015b). Phillyrin (lignan, 41) reduced proinflammatory cytokine production mainly by inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB activation in LPS-induced ALI (Zhong et al., 2013b). The same action mechanisms were also demonstrated by schisantherin A (53) treatment inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB activation (Zhou et al., 2014). It is important to mention that berberine (12) intraperitoneally injected reduced the inflammatory response of cigarette smoke-induced COPD model in mice. The compound inhibited the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 MAPK activation in lung tissue (Xu et al., 2015). Shikonin (52) and stevioside (54) reduced the inflammatory response of LPS-induced ALI by inhibiting NF-κB activation (Bai et al., 2013; Yingkun et al., 2013). Asperuloside (iridoid, 9) inhibited LPS-induced ALI mainly via the inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB activation (Qiu et al., 2016). Prime-O-glucosylcimifugin (chromone, 45) also inhibited lung inflammation by a similar mechanism of MAPK and NF-κB inhibition (Chen et al., 2013). Although many compounds have been found to attenuate lung inflammation by interrupting the MAPK and NF-κB pathways, it is interesting that cannabidiol (14) inhibited LPS-induced ALI at least partly by stimulating the adenosine A(2A) receptor (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Part of the attenuating effect of eriodictyol (21) against LPS-induced ALI was due to the activation of the Nrf2 pathway (Zhu et al., 2015).

Most of all, various flavonoids have been shown to inhibit lung inflammation. Flavonoids are well-known anti-inflammatory plant constituents. Certain flavonoids have shown inhibitory action in various animal models of inflammation. For example, some flavonoids were revealed to inhibit the animal models of acute inflammation: paw edema, ear edema and pleurisy. They also inhibited animal models of chronic inflammation: adjuvant-induced arthritis and collagen-induced arthritis. Certain derivatives inhibited lung inflammation. Flavone derivatives including flavone (24), tricetin (26), luteolin (32), apigenin-7-glucoside (7), baicalein (10) and baicalin (11), flavonol derivatives such as afzelin (2), hyperoside (3), quercitrin (4), morin (37), quercetin (47) and fisetin (25), isoflavones such as tectorigenin (56), flavanones such as eriodictyol (21), naringin (38), hesperidin (28) and sakuranetin (49) were demonstrated to possess inhibitory activity in lung inflammation models. Quercetin, baicalin and naringin orally administered were effective in the COPD model (Ganesan et al., 2010; Li et al., 2012a; Nie et al., 2012). Particularly, quercetin inhibited lung inflammation and mucus production in the cigarette smoke-induced COPD model (Yang et al., 2012). This inhibitory action might be mediated by inhibiting oxidative stress, inhibiting NF-κB activation and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation. The structurally related flavonoid, baicalein, inhibited LPS-induced ALI in rats by augmenting Nrf2/HO-1 pathways and inhibiting NF-κB activation (Tsai et al., 2014). Luteolin reduced lung inflammation possibly by inhibiting NF-κB activation via the inhibition of MAPK and AKT/Protein kinase B (Lee et al., 2010). Fisetin treatment by oral administration reduced proinflammatory molecule production such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-2 and IκBα (Geraets et al., 2009). Similar inhibitory mechanisms were revealed in tectorigenin which reduced lung inflammation via inhibiting the p65 NF-κB component (Ma et al., 2014). Hesperidin reduced the production of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-6, whereas it increased the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10. These actions of hesperidin might be mediated by the interruption of NF-κB and AP-1 pathways (Yeh et al., 2007a). Thus it is concluded that certain flavonoids act as inhibitory agents against lung inflammatory diseases. Their action mechanisms include anti-oxidative action and NF-κB inhibition. Indeed, herbal extracts that have flavonoids as major constituents have been used against lung inflammation. For example, Morus alba, which contains prenylated flavonoids as major constituents, has been used in traditional medicine to treat lung inflammatory disorders (Nomura, 2001). Scutellaria baicalensis has also been used in lung inflammatory conditions. This plant material contains various types of flavone derivatives such as baicalein and baicalin. Baicalein and especially baicalin exert strong inhibitory action against acute as well as chronic lung inflammation by oral administration (Huang et al., 2008; Li et al., 2012a).

In the elastase-induced emphysema model, NF-κB was also activated in the lung tissue. Under this condition, sakuranetin reduced the NF-κB response (Taguchi et al., 2015). It also regulated the expression of MMPs. In the elastase/LPS-induced COPD model, quercetin reduced inflammatory responses with concomitant inhibition of MMP-9 and −12 (Ganesan et al., 2010).

Other groups of plant constituents also demonstrated inhibitory action on lung inflammation. Some diterpenoids and triterpenoids have demonstrated inhibitory activity against lung inflammation. For instance, the triterpenoid saponins are major constituents of Hedera helix, which is used for lung inflammation (Gepdiremen et al., 2005; Hocaoglu et al., 2012). Platycodin D (44), a triterpenoid saponin from Platycodon grandiflorum, also showed inhibitory action against ALI (Tao et al., 2015). This compound was found to inhibit the expression of NF-κB, caspase-3 and Bax. P. grandiflorum has been used as an expectorant (State Pharmacopoeia Commission of PR China, 2000). Methyl protodioscin (34), a steroidal saponin, showed inhibitory action agaisnt LPS-induced ALI at 30–60 mg/kg (Lee et al., 2015c). Taraxasterol (55) from Taraxacum officinale, in this case through intraperitoneal injection, showed inhibitory action against lung inflammation (San et al., 2014). This inhibitory action was mediated by the inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Another triterpene derivative, mogroside V (35), reduced lung inflammation by the downregulation of COX-2 and iNOS via inhibiting NF-κB activation (Shi et al., 2014). The famous diterpenoid, triptolide (57) from Trypterygium wilfordii, was also shown to inhibit LPS-induced lung inflammation at concentrations as low as 1 mg/kg via intraperitoneal injection (Wei and Huang, 2014). Especially, triptolide inhibited the activation of MAPK and NF-κB pathways, and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression in LPS-induced ALI in mice. Esculentoside A (saponin, 22) also reduced TNF-α and IL-6 production possibly via inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB pathways (Zhong et al., 2013a).

Some coumarin derivatives also possess inhibitory action against lung inflammation. Examples are columbianadin (17), esculin (23) and imperatorin (29) (Sun et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2014; Tianzhu and Shumin, 2015). Esculin inhibited LPS-induced ALI by inhibiting the activation of myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) (an upstream molecule of NF-κB) and NF-κB p65 activation (Tianzhu and Shumin, 2015).

Recently, moracin M (arylbenzofuran, 36) was found to inhibit LPS-induced ALI at 20–60 mg/kg (Lee et al., 2016). Moracin M was found to suppress NF-κB activation in the inflamed lung. This compound is a minor constituent in Morus alba, which showed significant inhibition against the same animal model (Lim et al., 2013). These results may support the scientific basis of M. alba for treating lung diseases.

As described above, reports on many plant constituents demonstrating inhibitory action on lung inflammation are increasing continuously, and some have demonstrated promising results. In the near future, the clinical effectiveness of some molecules may be proven in human trials.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

Various plant extracts possess potential therapeutic effectiveness against lung inflammatory disorders including COPD. Additionally, many different classes of plant constituents were found to inhibit inflammatory responses in the lung. Especially, flavonoids are promising therapeutics since they affect signaling pathways essential to lung inflammation.

Up to the present, the regulatory effects of many natural products on NF-κB activation have been widely demonstrated. Despite the importance of NF-κB in lung inflammatory disorders, there are some contradicting results showing that NF-κB does not exert a role in cigarette smoke-induced COPD models of mice and in human lungs (Rastrick et al., 2013). Other cellular pathways need to be evaluated to examine the effectiveness of natural products. For instance, sirtuins were recently described as target molecules in COPD disorders. MMPs are also important for controlling lung elasticity. With continuous study, some plant extracts and constituents will hopefully be developed as new disease modifying drugs acting on lung inflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2016R1A2B4007756), 2016 Research Grant from Kangwon National University (No. 520160100) and BK21 PLUS program from the Ministry of Education, Republic of Korea.

REFERENCES

- Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Maltais F, Field SK, Sin DD, Bourbeau J, Marciniuk DD, FitzGerald JM, Nair P, Mallick R. TNFα antagonists for acute exacerbations of COPD: a randomised double-blind controlled trial. Thorax. 2013;68:142–148. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbabiaka TB, Guo R, Ernst E. Pelargonium sidoides for acute bronchitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babayigit A, Olmez D, Karaman O, Ozogul C, Yilmaz O, Kivcak B, Erbil G, Uzuner N. Effects of Ginkgo biloba on airway histology in a mouse model of chronic asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:186–191. doi: 10.2500/aap.2009.30.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachoual R, Talmoudi W, Boussetta T, Braut F, El-Benna J. An aqueous pomegranate peel extract inhibits neutrophil myeloperoxidase in vitro and attenuates lung inflammation in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:1224–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Kim R, Kim Y, Lee E, Kim HJ, Jang YP, Jung S-K, Kim J. Effects of Schisandra chinensis Baillon (Schizandraceae) on lipopolysaccharide induced lung inflammation in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;142:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai GZ, Yu HT, Ni YF, Li XF, Zhang ZP, Su K, Lei J, Liu BY, Ke CK, Zhong DX, Wang YJ, Zhao JB. Shikonin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Surg Res. 2013;182:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brightling CE, Bleecker ER, Panettieri RA, Jr, Bafadhel M, She D, Ward CK, Xu X, Birrell C, van der Merwe R. Benralizumab for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sputum eosinophilia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:891–901. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70187-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Wu Q, Chi G, Soromou LW, Hou J, Deng Y, Feng H. Prime-O-glucosylcimifugin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;16:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi G, Wei M, Xie X, Soromou LW, Liu F, Zhao S. Suppression of MAPK and NF-κB pathways by limonene contributes to attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in acute lung injury. Inflammation. 2013;36:501–511. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Kwun MJ, Kim KH, Lyu JH, Han CW, Jeong HS, Ha KT, Jung HJ, Lee BJ, Sadikot RT, Christman JW, Jung SK, Joo M. Protective effect of the fruit hull of Gleditsia sinensis on LPS-induced acute lung injury is associated with Nrf2 activation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:974713. doi: 10.1155/2012/974713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CJ, Xu NY, Li XL, Xia L, Zhang J, Liang ZT, Zhao ZZ, Chen DF. Rabdosia japonica var. glaucocalyx flavonoids fraction attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:894515. doi: 10.1155/2014/894515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun P. Role of sirtuins in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Pharm Res. 2015;38:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12272-014-0494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A, Zhou S, Wright JL. Series “matrix metalloproteinases in lung health and disease”: Matrix metalloproteinases in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:197–209. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros FJ, Jayo M, Niedziela L. An Uncaria tomentosa (cat’s claw) extract protects mice against ozone-induced lung inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corhay JL, Henket M, Nguyen D, Duysinx B, Sele J, Louis R. Leukotriene B4 contributes to exhaled breath condensate and sputum neutrophil chemotaxis in COPD. Chest. 2009;136:1047–1054. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornélio Favarin D, Martins Teixeira M, Lemos de Andrade E, de Freitas Alves C, Lazo Chica JE, Arterio Sorgi C, Faccioli LH, Paula Rogerio A. Anti-inflammatory effects of ellagic acid on acute lung injury induced by acid in mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:164202. doi: 10.1155/2013/164202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Chan YP, Chu LM, Bu PP. Antiallergic and anti-inflammatory properties of the ethanolic extract from Gleditsia sinensis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:1179–1182. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Melo GO, Muzitano MF, Legora-Machado A, Almeida TA, De Oliveira DB, Kaiser CR, Koatz VL, Costa SS. C-glycosylflavones from the aerial parts of Eleusine indica inhibit LPS-induced mouse lung inflammation. Planta Med. 2005;71:362–363. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentener MA, Creutzberg EC, Pennings HJ, Rijkers GT, Mercken E, Wouters EF. Effect of infliximab on local and systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. Respiration. 2008;76:275–282. doi: 10.1159/000117386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly LE, Newton R, Kennedy GE, Fenwick PS, Leung RH, Ito K, Russell RE, Barnes PJ. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol in lung epithelial cells: molecular mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L774–L783. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00110.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doukas J, Eide L, Stebbins K, Racanelli-Layton A, Dellamary L, Martin M, Dneprovskaia E, Noronha G, Soll R, Wrasidlo W, Acevedo LM, Cheresh DA. Aerosolized phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma/delta inhibitor TG100-115 [3-[2,4-diamino-6-(3-hydroxyphenyl)pteridin-7-yl]phenol] as a therapeutic candidate for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:758–765. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.144311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favarin DC, de Oliveira JR, de Oliveira CJ, de Paula Rogerio A. Potential effects of medicinal plants and secondary metabolites on acute lung injury. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:576479. doi: 10.1155/2013/576479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei XJ, Zhu LL, Xia LM, Peng WB, Wang Q. Acanthopanax senticosus attenuates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:10537–10544. doi: 10.4238/2014.December.12.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Jia A. Protective effect of carvacrol on acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Inflammation. 2014;37:1091–1101. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9833-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciosi LG, Diamant Z, Banner KH, Zuiker R, Morelli N, Kamerling IM, de Kam ML, Burggraaf J, Cohen AF, Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Singh D, Spina D, Walker MJ, Page CP. Efficacy and safety of RPL554, a dual PDE3 and PDE4 inhibitor, in healthy volunteers and in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: findings from four clinical trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:714–727. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas TP, Silveira PC, Rocha LG, Rezin GT, Rocha J, Citadini-Zanette V, Romao PT, Dal-Pizzol F, Pinho RA, Andrade VM, Streck EL. Effects of Mikania glomerata Spreng. and Mikania laevigata Schultz Bip. ex Baker (Asteraceae) extracts on pulmonary inflammation and oxidative stress caused by acute coal dust exposure. J. Med. Food. 2008;11:761–766. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu PK, Yang CY, Tsai TH, Hsieh CL. Moutan cortex radicis improves lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats through anti-inflammation. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:1206–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S, Faris AN, Comstock AT, Chattoraj S, Chattoraj A, Burgess JR, Curtis JL, Martinez FJ, Zick S, Hershenson MB, Sajjan U. Quercetin prevents progression of disease in elastase/LPS-exposed mice by negatively regulating MMP expression. Respir Res. 2010;11:131. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepdiremen A, Mshvildadze V, Süleyman H, Elias R. Acute anti-inflammatory activity of four saponins isolated from ivy: alpha-hederin, hederasaponin-C, hederacolchiside-E and hederacolchiside-F in carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraets L, Haegens A, Brauers K, Haydock JA, Vernoony JHJ, Wouters EFM, Bast A, Hageman GJ. Inhibition of LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation by specific flavonoids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Shenkman Z, Bleiberg B, Dayan M, Gillelson M, Efrat R. Ginseng improves pulmonary functions and exercise capacity in patients with COPD. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2002;57:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R, Pittier MH, Ernst E. Herbal medicines for the treatment of COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:330–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00119905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HH, Park SY, Ko WS, Kim YH. Gleditsia sinensis thorns inhibit the production of NO through NF-κB suppression in LPS-stimulated macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;118:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CW, Kwun MJ, Kim KH, Choi JY, Oh SR, Ahn KS, Lee JH, Joo M. Ethanol extract of Alismatis rhizoma reduces acute lung inflammation by suppressing NF-κB and activating Nrf2. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesslinger C, Strub A, Boer R, Ulrich WR, Lehner MD, Braun C. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase in respiratory diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:886–891. doi: 10.1042/BST0370886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocaoglu AB, Karaman O, Erge DO, Erbil G, Yilmaz O, Kivcak B, Bagriyanik HA, Uzuner N. Effect of Hedera helix on lung histopathology in chronic asthma. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;11:316–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E-H, Song J-H, Shim A, Lee B-R, Kwon B-E, Song H-H, Kim Y-J, Chang S-Y, Jeong HG, Kim JG, Seo S-U, Kim HP, Kwon YS, Ko H-J. Coadministration of Hedera helix L. extract enabled mice to overcome insufficient protection against influenza A/PR/8 virus infection under suboptimal treatment with oseltamivir. PLoS ONE. 2015a;10:e0131089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JM, Kwon OK, Shin IS, Jeon CM, Shin NR, Lee J, Park SH, Bach TT, Hai do V, Oh SR, Han SB, Ahn KS. Anti-inflammatory effects of methanol extract of Canarium lyi C.D. Dai & Yakovlev in RAW 264.7 macrophages and a murine model of lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Int J Mol Med. 2015b;35:1403–1410. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossein BM, Nasim V, Sediga A. The protective effect of Nigella sativa on lung injury of sulfur mustard-exposed guinea pigs. Exp Lung Res. 2008;34:183–194. doi: 10.1080/01902140801935082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinian N, Cho Y, Lockey RF, Kolliputi N. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in pulmonary diseases. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2015;9:188–197. doi: 10.1177/1753465815586335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Yang ML, Tsai CH, Li YC, Lin YJ, Kuan YH. Ginkgo biloba leaves extract (EGb761) attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibition of oxidative stress and NF-κB-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 pathway. Phytomedicine. 2013;20:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GJ, Deng JS, Chen CC, Huang CJ, Sung PJ, Huang SS, Kuo YH. Methanol extract of Antrodia camphorata protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by suppressing NF-κB and MAPK pathways in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2014a;62:5321–5329. doi: 10.1021/jf405113g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Hu G, Wang C, Xu H, Chen X, Qian A. Cepharanthine, an alkaloid from Stephania cepharantha Hayata, inhibits the inflammatory response in the RAW264.7 cell and mouse models. Inflammation. 2014b;37:235–246. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang KL, Chen CS, Hsu CW, Li MH, Chang H, Tsai SH, Chu SJ. Therapeutic effects of baicalin on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36:301–311. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X08005783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M, Chen N, Chi G, Yuan X, Guan S, Li H, Zhong W, Guo W, Soromou LW, Gao R, Ouyang H, Deng X, Feng H. Traditional medicine alpinetin inhibits the inflammatory response in Raw 264.7 cells and mouse models. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;12:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M, Cui X, Xue J, Chi G, Gao R, Deng X, Guan S, Wei J, Soromou LW, Feng H, Wang D. Anti-inflammatory effects of linalool in RAW 264.7 macrophages and lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury model. J Surg Res. 2013a;180:e47–e54. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M, Gao R, Jiang L, Cui X, Duan L, Deng X, Guan S, Wei J, Soromou LW, Feng H, Chi G. Suppression of LPS-induced inflammatory responses by gossypol in RAW 264.7 cells and mouse models. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013b;15:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilieva I, Ohgami K, Shiratori K, Koyama Y, Yoshida K, Kase S, Kitamei H, Takemoto Y, Yazawa K, Ohno S. The effects of Ginkgo biloba extract on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing W, Chunhua M, Shumin W. Effects of acteoside on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in acute lung injury via regulation of NF-κB pathway in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;285:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao ST, Liu CJ, Yeh CC. Protective and immunomodulatory effect of flos Lonicerae japonicae by augmenting IL-10 expression in a murine model of acute lung inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;168:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cha YN, Surh YJ. A protective role of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) in inflammatory disorders. Mutat Res. 2010;690:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS, Kim HP. Inhibition of mouse ear edema by steroidal and triterpenoid saponins. Arch Pharm Res. 1999;22:313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF02976370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HJ, Jin JH, Kwon OS, Kim JT, Son KH, Kim HP. Inhibition of experimental lung inflammation and bronchitis by phytoformula containing Broussonetia papyrifera and Lonicera japonica. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2011;19:324–330. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2011.19.3.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul A, Kapoor N, Bharati S. Histopathological, enzymatic, and molecular alterations induced by cigarette smoke inhalation in the pulmonary tissue of mice and its amelioration by aqueous Azadirachta indica leaf extract. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2012;31:7–15. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.v31.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak HG, Lim HB. Inhibitory effects of Cnidium monnieri fruit extract on pulmonary inflammation in mice induced by cigarette smoke condensate and lipopolysaccharide. Chin J Nat Med. 2014;12:641–647. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(14)60098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Jung KH, Park S, Kil YS, Chung EY, Jang YP, Seo EK, Bae H. Inhibitory effects of Stemona tuberosa on lung inflammation in a subacute cigarette smoke-induced mouse model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:513. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kim Y, Kim HJ, Park S, Jang YP, Jung S, Jung H, Bae H. Herbal Formula, PM014, attenuates lung inflammation in a murine model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:769830. doi: 10.1155/2012/769830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Yu SR, Lim D, Lee H, Jin EY, Jang YP, Kim J. Galla chinensis attenuates cigarette smoke-associated lung injury by inhibiting recruitment of inflammatory cells into the lung. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015a;116:222–228. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Ahn J, Kim JW, Lee SG, Kim HP. Flavonoids from the aerial parts of Houttuynia cordata attenuate lung inflammation in mice. Arch Pharm Res. 2015b;38:1304–1311. doi: 10.1007/s12272-015-0585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Ko HJ, Woo ER, Lee SK, Moon BS, Lee CW, Mandava S, Samala M, Lee J, Kim HP. Moracin M inhibits airway inflammation by interrupting the JNK/c-Jun and NF-κB pathways in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;783:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Lim HJ, Lee CW, Son KH, Son JK, Lee SK, Kim HP. Methyl protodioscin from the roots of Asparagus cochinchinensis attenuates airway inflammation by inhibiting cytokine production. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015c;2015:640846. doi: 10.1155/2015/640846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JP, Li YC, Chen HY, Lin RH, Huang SS, Chen HL, Kuan PC, Liao MF, Chen CJ, Kuan YH. Protective effects of luteolin against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury involves inhibition of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways in neutrophils. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:831–838. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Shin NR, Park JW, Park SY, Kwon OK, Lee HS, Kim JH, Lee HJ, Lee J, Zhang ZY, Oh SR, Ahn KS. Callicarpa japonica Thunb. attenuates cigarette smoke-induced neutrophil inflammation and mucus secretion. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015d;175:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Shin EJ, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS, Kim HP. Anti-inflammatory activity of the major constituents of Lonicera japonica. Arch Pharm Res. 1995;18:133–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02979147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS, Kim HP. Antiinflammatory activity of Lonicera japonica. Phytother Res. 1998;12:445–447. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199809)12:6<445::AID-PTR317>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li KC, Ho YL, Hsieh WT, Huang SS, Chang YS, Huang GJ. Apigenin-7-glycoside prevents LPS-induced acute lung injury via downregulation of oxidative enzyme expression and protein activation through inhibition of MAPK phosphorylation. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:1736–1754. doi: 10.3390/ijms16011736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bao H, Wu J, Duan X, Liu B, Sun J, Gong W, Lv Y, Zhang H, Luo Q, Wu X, Dong J. Baicalin is anti-inflammatory in cigarette smoke-induced inflammatory models in vivo and in vitro: A possible role for HDAC2 activity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012a;13:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Xie JY, Li H, Zhang YY, Cao J, Cheng ZH, Chen DF. Viola yedoensis liposoluble fraction ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Am J Chin Med. 2012b;40:1007–1018. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HJ, Jin HG, Woo ER, Lee SK, Kim HP. The root barks of Morus alba and the flavonoid constituents inhibit airway inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HJ, Lee JH, Choi JS, Lee SK, Kim YS, Kim HP. Inhibition of airway inflammation by the roots of Angelica decursiva and its constituent, columbianadin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:1353–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J-C, Park JH, Budensinsky M, Kasal A, Han Y-H, Koo B-S, Lee S-I, Lee D-U. Antimutagenic constituents from the thorns of Gleditsia sinensis. Chem Pharm Bull. 2005;53:561–564. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Ren J, Chen H, Huang Y, Li H, Zhang Z, Wang J. Resveratrol protects against cigarette smoke-induced oxidative damage and pulmonary inflammation. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2014a;28:465–471. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Xiong H, Ping J, Ju Y, Zhang X. Taraxacum officinale protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MH, Lin AH, Lee HF, Ko HK, Lee TS, Kou YR. Paeonol attenuates cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation by inhibiting ROS-sensitive inflammatory signaling. Mediators Inflamm. 2014b;2014:651890. doi: 10.1155/2014/651890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu JH, Kim KH, Kim HW, Cho SI, Ha KT, Choi JY, Han CW, Jeong HS, Lee HK, Ahn KS, Oh SR, Sadikot RT, Christman JW, Joo M. Dangkwisoo-san, an herbal medicinal formula, ameliorates acute lung inflammation via activation of Nrf2 and suppression of NF-κB. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Zhu L, Wang J, He H, Chang X, Gao J, Shumin W, Yan T. Anti-inflammatory effects of water extract of Taraxacum mongolicum hand.-Mazz on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in acute lung injury by suppressing PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015a;168:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma CH, Liu JP, Qu R, Ma SP. Tectorigenin inhibits the inflammation of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice. Chin J Nat Med. 2014;12:841–846. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(14)60126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Xu H, Wu J, Qu C, Sun F, Xu S. Linalool inhibits cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015b;29:708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler DA, Huang S, Tabrizi M, Bell GM. Efficacy and safety of a monoclonal antibody recognizing interleukin-8 in COPD: a pilot study. Chest. 2004;126:926–934. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao YF, Li YQ, Zong L, You XM, Lin FQ, Jiang L. Methanol extract of Phellodendri cortex alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute airway inflammation in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2010;32:110–115. doi: 10.3109/08923970903193325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks-Konczalik J, Costa M, Robertson J, McKie E, Yang S, Pascoe S. A post-hoc subgroup analysis of data from a six month clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of losmapimod in moderate-severe COPD patients with ≤2% and >2% blood eosinophils. Respir Med. 2015;109:860–869. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys H, Funk P. EPs 7630 improves acute bronchitic symptoms and shortens time to remission. Results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Planta Med. 2008;74:686–692. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L379–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto N, Caruso P, Bosco R, Marchini G, Pastore F, Armani E, Amari G, Rizzi A, Ghidini E, De Fanti R, Capaldi C, Carzaniga L, Hirsch E, Buccellati C, Sala A, Carnini C, Patacchini R, Delcanale M, Civelli M, Villetti G, Facchinetti F. CHF6001 I: a novel highly potent and selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor with robust anti-inflammatory activity and suitable for topical pulmonary administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;352:559–567. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.220541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A, Kinnear G, Wan WY, Wyss D, Bahra P, Stevenson CS. Comparison of cigarette smoke-induced acute inflammation in multiple strains of mice and the effect of a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor on these responses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:851–862. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.140848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura RS, Ferreira TS, Lopes AA, Pires KM, Nesi RT, Resende AC, Souza PJ, Silva AJ, Borges RM, Porto LC, Valenca SS. Effects of Euterpe oleracea Mart. (AçAÍ) extract in acute lung inflammation induced by cigarette smoke in the mouse. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntuschi P, Kharitonov SA, Ciabattoni G, Barnes PJ. Exhaled leukotrienes and prostaglandins in COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:585–588. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie YC, Wu H, Li PB, Luo YL, Long K, Xie LM, Shen JG, Su WW. Anti-inflammatory effects of naringin in chronic pulmonary neutrophilic inflammation in cigarette smoke-exposed rats. J. Med. Food. 2012;15:894–900. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Ahn KS, Oh SR, Kim KH, Joo M. Neutrophilic lung inflammation suppressed by picroside II is associated with TGF-β signaling. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:897272. doi: 10.1155/2015/897272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T. Chemistry and biosynthesis of prenylflavonoids. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2001;121:535–556. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.121.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P. Evidence on the identity of the CXCR2 antagonist AZD-5069. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23:113–117. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.725724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P. Investigational p38 inhibitors for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2015;24:383–392. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1006358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinner NA, Hamilton LA, Hughes A. Roflumilast: a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor for the treatment of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Ther. 2012;34:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qamar W, Sultana S. Polyphenols from Juglans regia L. (walnut) kernel modulate cigarette smoke extract induced acute inflammation, oxidative stress and lung injury in Wistar rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2011;30:499–506. doi: 10.1177/0960327110374204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Chi G, Wu Q, Ren Y, Chen C, Feng H. Pretreatment with the compound asperuloside decreases acute lung injury via inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB signaling in a murine model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;31:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastrick JM, Stevenson CS, Eltom S, Grace M, Davies M, Kilty I, Evans SM, Pasparakis M, Catley MC, Lawrence T, Adcock IM, Belvisi MG, Birrell MA. Cigarette smoke induced airway inflammation is independent of NF-κB signalling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid DJ, Pham NT. Roflumilast: a novel treatment for chronic pulmonary disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:521–529. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennard SI, Dale DC, Donohue JF, Kanniess F, Magnussen H, Sutherland ER, Watz H, Lu S, Stryszak P, Rosenberg E, Staudinger H. CXCR2 Antagonist MK-7123. A phase 2 proof-of-concept trial for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1001–1011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0992OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A, Ferraz-Paula V, Pinheiro ML, Vitoretti LB, Mariano-Souza DP, Quinteiro-Filho WM, Akamine AT, Almeida VI, Quevedo J, Dal-Pizzol F, Hallak JE, Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Palermo-Neto J. Cannabidiol, a non-psychotropic plant-derived cannabinoid, decreases inflammation in a murine model of acute lung injury: role for the adenosine A(2A) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;678:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M, Woods CR, Mora AL, Xu J, Brigham KL. Endotoxin-induced lung injury in mice: structural, functional, and biochemical responses. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L333–L341. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00334.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovina N, Dima E, Gerassimou C, Kollintza A, Gratziou C, Roussos C. Interleukin-18 in induced sputum: association with lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2009;103:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Z, Fu Y, Li W, Zhou E, Li Y, Song X, Wang T, Tian Y, Wei Z, Yao M, Cao Y, Zhang N. Protective effect of taraxasterol on acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana FP, Pinheiro NM, Mernak MI, Righetti RF, Martins MA, Lago JH, Lopes FD, Tiberio IF, Prado CM. Evidence of herbal medicine-derived natural products effects in inflammatory lung diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:2348968. doi: 10.1155/2016/2348968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuliga M. NF-kappaB signaling in chronic inflammatory airway disease. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1266–1283. doi: 10.3390/biom5031266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimetz M, Parajuli N, Pichl A, Veit F, Kwapiszewska G, Weisel FC, Milger K, Egemnazarov B, Turowska A, Fuchs B, Nikam S, Roth M, Sydykov A, Medebach T, Klepetko W, Jaksch P, Dumitrascu R, Garn H, Voswinckel R, Kostin S, Seeger W, Schermuly RT, Grimminger F, Ghofrani HA, Weissmann N. Inducible NOS inhibition reverses tobacco-smoke-induced emphysema and pulmonary hypertension in mice. Cell. 2011;147:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sezer M, Sahin O, Solak O, Fidan F, Kara Z, Unlu M. Effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on the histopathological changes in the lungs of cigarette smoke-exposed rabbits. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;101:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafkhaneh A, Velamuri S, Badmaev V, Lan C, Hanania N. The potential role of natural agents in treatment of airway inflammation. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2007;1:105–120. doi: 10.1177/1753465807086096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Arnason JT, Burt A, Hudson JB. Echinacea extracts modulate the pattern of chemokine and cytokine secretion in rhinovirus-infected and uninfected epithelial cells. Phytother Res. 2006;20:147–152. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D, Zheng M, Wang Y, Liu C, Chen S. Protective effects and mechanisms of mogroside V on LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice. Pharm Biol. 2014;52:729–734. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.867451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim DW, Han JW, Sun X, Jang CH, Koppula S, Kim TJ, Kang TB, Lee KH. Lysimachia clethroides Duby extract attenuates inflammatory response in Raw 264.7 macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and in acute lung injury mouse model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soromou LW, Chu X, Jiang L, Wei M, Huo M, Chen N, Guan N, Yang X, Chen C, Feng H, Deng X. In vitro and in vivo protection provided by pinocembrin against lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriskantharajah S, Hamblin N, Worsley S, Calver AR, Hessel EM, Amour A. Targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ for the treatment of respiratory diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1280:35–39. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State Pharmacopoeia Commission of PR China . Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Vol. 1. Chemical Industry Press; Beijing: 2000. pp. 225–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stolk J, Rossie W, Dijkman JH. Apocynin improves the efficacy of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor in experimental emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1628–1631. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.6.7952625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZQ, Mo ZZ, Liao JB, Feng XX, Liang YZ, Zhang X, Liu YH, Chen XY, Chen ZW, Su ZR, Lai XP. Usnic acid protects LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice through attenuating inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;22:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Chi G, Soromou LW, Chen N, Guan M, Wu Q, Wang D, Li H. Preventive effect of imperatorin on acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi L, Pinheiro NM, Olivo CR, Choqueta-Toledo A, Grecco SS, Lopes FD, Caperuto LC, Martins MA, Tiberio IF, Camara NO, Lago JH, Prado CM. A flavanone from Baccharis retusa (Asteraceae) prevents elastase-induced emphysema in mice by regulating NF-κB, oxidative stress and metalloproteinases. Respir Res. 2015;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0233-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima S, Bando M, Yamasawa H, Ohno S, Moriyama H, Takada T, Suzuki E, Geiyo F, Sigiyama Y. Preventive effect of Hochu-ekki-to on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in BALB/c mice. Lung. 2006;184:318–323. doi: 10.1007/s00408-006-0018-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W, Su Q, Wang H, Guo S, Chen Y, Duan J, Wang S. Platycodin D attenuates acute lung injury by suppressing apoptosis and inflammation in vivo and in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;27:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tianzhu Z, Shihai Y, Juan D. The effects of morin on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by suppressing the lung NLRP3 inflammasome. Inflammation. 2014;37:1976–1983. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tianzhu Z, Shumin W. Esculin inhibits the inflammation of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice via regulation of TLR/NF-κB pathways. Inflammation. 2015;38:1529–1536. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0127-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]