Abstract

Introduction

Over time there has been substantial improvement in antiretroviral treatment (ART) programmes, including expansion of services and increased patient engagement. We describe time trends in, and factors associated with, loss to follow-up (LTFU) in HIV-positive patients receiving ART in Asia.

Methods

Analysis included HIV-positive adults initiating ART in 2003-2013 at seven ART programmes in Asia. Patients LTFU had not attended the clinic for ≥180 days, had not died or transferred to another clinic. Patients were censored at recent clinic visit, follow-up to January 2014. We used cumulative incidence to compare LTFU and mortality between years of ART initiation. Factors associated with LTFU were evaluated using a competing risks regression model, adjusted for clinical site.

Results

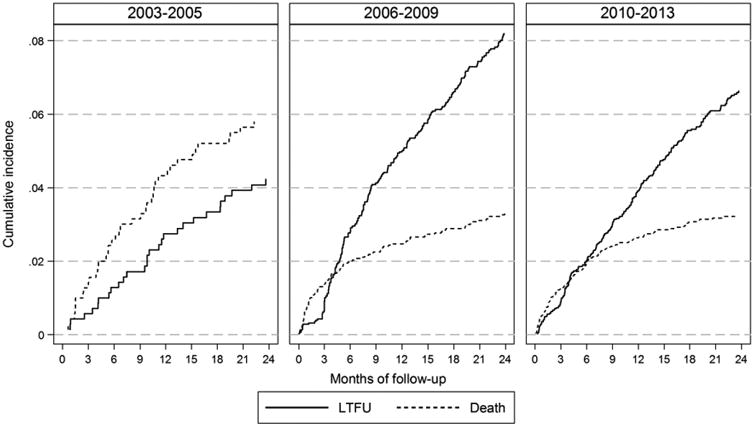

A total of 8,305 patients were included. There were 743 patients LTFU and 352 deaths over 26,217 person-years (pys), a crude LTFU and mortality rate of 2.83 (2.64-3.05) per 100 pys and 1.34 (1.21-1.49) per 100 pys, respectively. At 24 months, the cumulative LTFU incidence increased from 4.3%(2.9-6.1%) in 2003-05 to 8.1%(7.1-9.2%) in 2006-09, then decreased to 6.7%(5.9-7.5%) in 2010-13. Concurrently, the cumulative mortality incidence decreased from 6.2%(4.5-8.2%) in 2003-05 to 3.3%(2.8-3.9%) in 2010-13. The risk of LTFU reduced in 2010-13 compared to 2006-09 (adjusted subhazard ratio=0.73, 0.69-0.99).

Conclusions

LTFU rates in HIV-positive patients receiving ART in our clinical sites have varied by the year of ART initiation, with rates declining in recent years while mortality rates have remained stable. Further increases in site-level resources are likely to contribute to additional reductions in LTFU for patients initiating in subsequent years.

Keywords: Asia, HIV, epidemiology, retention in care, loss to follow-up, ART

Introduction

The expansion of antiretroviral treatment (ART) has had substantial impact on the outcomes of HIV-positive patients. However, HIV care requires lifelong ART which causes a considerable burden on ART programmes to retain patients in-care. Many ART programmes and cohort studies have shown large numbers of patients lost to follow-up (LTFU) following ART initiation. Studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have reported high rates of LTFU within 6 months following ART initiation1. More than half the patients receiving ART in two care and treatment centres in Tanzania were LTFU within 3 months of ART initiation2. While a systematic review of patient retention in sub-Saharan Africa after ART initiation found that LTFU exceeded death as the cause of patient attrition (59% vs 41%)3.

In addition, there are significant clinical implications for patients who are LTFU. Patients who are LTFU often have high mortality rates, particularly from low-income countries4-8. Unreported deaths in LTFU patients can also bias findings from analyses, particularly in time-to-event analyses9,10. There is also a risk that LTFU patients will discontinue or interrupt ART. One study in Malawi reported that of the 2 183 LTFU patients who had initiated ART, 1 250 (57.3%) had either stopped or interrupted ART after being LTFU11. These treatment interruptions are concerning as they may lead to viral rebound and an increased chance of HIV transmission and drug resistance12. CD4 cell count restoration and overall prognosis are also hindered during periods of ART interruption13-15. Hence, there is a strong need to retain patients in care to achieve better patient outcomes and reduce the transmission of HIV through sustained viral suppression.

There have been substantial improvements in ART programmes globally to retain HIV-positive patients in long-term care16,17. Previous studies have highlighted that the use of support services offered by HIV programmes is associated with increased engagement in-case18,19. The HIV cascade of care describes how patients move between stages of care, from HIV diagnosis, to linkage and retention in care, to ART initiation and viral load suppression20. The cascade of care highlights the importance of all stages of HIV care and, ideally, 90% or more of patients will achieve each stage21. However, disparities in the continuum of care do occur and, as ART scale-up continues, there may be an increased proportion of patients LTFU22. As patients receiving ART continue to increase, HIV programmes have a limited capacity to maintain the quality of care provided and retention in long-term care becomes more challenging23. Over the past decade, treatment coverage in Asia has substantially increased from 19% in 2010 to 41% in 2015, with an estimated 2.1 million people receiving ART16. Yet, Asia is a diverse region with the HIV epidemic considered as concentrated in particular high risk populations and countries including India and Cambodia24. Monitoring patient retention rates in Asia is important to ensure the long-term success of HIV treatment services in the region. Our study objective was to analyse and describe time trends in and factors associated with LTFU in HIV-positive patients receiving ART in Asia.

Methods

Data collection and Participants

We used observational patient data collected in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational database Low Intensity TransfEr (TAHOD-LITE), a sub-study of the TREAT Asia HIV Observational database (TAHOD), member cohorts of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDs (IeDEA)25. Currently, TAHOD collects prospective data on a subset of patients attending 20 treatment sites in Asia and TAHOD-LITE collects retrospective data on all patients seen at 8 of the 20 treatment sites, including one each in Cambodia, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Singapore, and South Korea, and two in Vietnam. A more detailed description of TAHOD-LITE has been previously described26. Briefly, routine patient data collected at the treatment site are anonymized and then electronically transferred for data management and analysis at the Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia. Patient data are limited to demographics, hepatitis serology, ART history and HIV-related laboratory results. TAHOD-LITE was granted ethics approvals from Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at each participating site, the University of New South Wales and the coordinating center at TREAT Asia/amfAR.

This analysis was limited to only 7 of the 8 sites that were able to distinguish LTFU from patient transfers to another clinical site for ongoing care. Hence, patient data were used from 7 sites representing 6 countries in Asia. Patients were eligible for inclusion if aged over 18 years, they had initiated an ART regimen consisting of three or more antiretroviral drugs from 01 January 2003 to 31 December 2013, and they had at least one subsequent follow-up visit after ART initiation.

Statistical analyses

Patients were defined as LTFU if they had not attended the clinic for at least 180 days and had not been transferred to another clinic or died. Sites determined whether patients had transferred to another clinic, either through clinic referral or self-referral to another clinic. Sites conducted their own patient tracing methods, according to local standards of practice, to identify patients who missed appointments and attempt to re-engage them into care or identify if they had been transferred to another clinic. No additional post-LTFU patient tracing was conducted as part of this study. The 180 day cut-off was selected as this has previously been validated in our cohort to achieve the highest sensitivity and specificity for determining LTFU patients27,28. Re-engagement into care after the first LTFU event was not considered. Hence, once patients were LTFU, subsequent follow-up was not included in the analysis. Follow-up was from the start of ART initiation to the date of death or most recent clinic visit, whichever occurred first. Patient follow-up was censored at 01 January 2014. We used a quasi intention-to-treat approach where changes to treatment after ART initiation were ignored.

Pre-ART laboratory results were defined as the result closest to and within 6 months prior to ART initiation. Patients were censored at most recent clinic visit and death was considered as a competing event. We used the observed cumulative incidence of LTFU to compare between year periods of ART initiation. Fine and Gray methods 29 for competing risks regression models were used to evaluate factors associated with LTFU, adjusted by clinical site. Covariates selected a priori only included age at ART initiation, sex, mode of HIV exposure, time-updated CD4 cell count (cells/μL), time-updated HIV viral load (copies/mL), first ART regimen, hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C co-infection (HCV).

Data were analysed using Stata version 14 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) and SAS software (Version 9.4 for Windows).

Results

A total of 8 382 patients from the seven eligible sites were aged over 18 years and had initiated ART between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2013. Of these, 77 patients (0.9%) were excluded as they did not have subsequent visits after ART initiation. The remaining 8 305 patients were included in our analysis.

Patient Characteristics

Overall, patients were male (69%), initiated ART in more recent year periods (2003-05: 9%; 2006-09: 33%; 2010-13: 58%) and had heterosexual contact as their reported mode of HIV exposure (66%). The median age was 35 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 30-44). The majority of patients had been tested at least once for HBV and HCV, and 9% and 12%, respectively, had ever tested positive. The median pre-ART CD4 cell count and pre-ART HIV viral load was 117 cells/μL (IQR: 32-239) and 105 000 copies/mL (IQR: 30 589-358 000), respectively. Most patients did not have previous mono/dual therapy (98%) and had initiated an ART regimen consisting of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) (92%). The largest proportion of patients were from Cambodia (30%), followed by Singapore (22%), Vietnam (19%), Indonesia (13%), Hong Kong (10%) and South Korea (6%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the patient characteristics across all countries.

| LTFU | In care | Deaths | All patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Total | 743 | 7210 | 352 | 8305 | (100) | |||

| Year of ART initiation | ||||||||

| 2003-05 | 67 | (9) | 564 | (8) | 75 | (21) | 706 | (9) |

| 2006-09 | 396 | (53) | 2240 | (31) | 124 | (35) | 2760 | (33) |

| 2010-13 | 280 | (38) | 4406 | (61) | 153 | (43) | 4839 | (58) |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤30 | 245 | (33) | 1986 | (28) | 69 | (20) | 2300 | (28) |

| 31-40 | 255 | (34) | 2950 | (41) | 131 | (37) | 3336 | (40) |

| 41-50 | 150 | (20) | 1399 | (19) | 68 | (19) | 1617 | (19) |

| 51+ | 93 | (13) | 875 | (12) | 84 | (24) | 1052 | (13) |

| Median [IQR] | 35 | [29, 44] | 35 | [30, 43] | 39 | [32, 50] | 35 | [30, 44] |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 503 | (68) | 4929 | (68) | 280 | (80) | 5712 | (69) |

| Female | 240 | (32) | 2276 | (32) | 69 | (20) | 2585 | (31) |

| Transgender | 0 | (-) | 5 | (0) | 3 | (1) | 8 | (<0.2) |

| Mode of HIV exposure | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 503 | (68) | 4805 | (67) | 213 | (61) | 5521 | (66) |

| Homosexual contact | 106 | (14) | 1113 | (15) | 34 | (10) | 1253 | (15) |

| Injecting drug user | 65 | (9) | 584 | (8) | 66 | (19) | 715 | (9) |

| Other/Unknown | 69 | (9) | 708 | (10) | 39 | (11) | 816 | (10) |

| HCV (ever) | ||||||||

| Negative | 499 | (67) | 5387 | (75) | 237 | (67) | 6123 | (74) |

| Positive | 73 | (10) | 819 | (11) | 68 | (19) | 960 | (12) |

| Not tested | 171 | (23) | 1004 | (14) | 47 | (13) | 1222 | (15) |

| HBV (ever) | ||||||||

| Negative | 519 | (70) | 5634 | (78) | 271 | (77) | 6424 | (77) |

| Positive | 59 | (8) | 634 | (9) | 40 | (11) | 733 | (9) |

| Not tested | 165 | (22) | 942 | (13) | 41 | (12) | 1148 | (14) |

| Pre-ART CD4 (cells/μL) | ||||||||

| ≤50 | 239 | (32) | 2104 | (29) | 174 | (49) | 2517 | (30) |

| 51-100 | 100 | (13) | 839 | (12) | 74 | (21) | 1013 | (12) |

| 101-200 | 154 | (21) | 1295 | (18) | 48 | (14) | 1497 | (18) |

| >200 | 194 | (26) | 2316 | (32) | 29 | (8) | 2539 | (31) |

| Not tested | 56 | (8) | 656 | (9) | 27 | (8) | 739 | (9) |

| Median [IQR] | 108 | [30, 217] | 126 | [34, 246] | 45 | [16, 97] | 117 | [32, 239] |

| Pre-ART viral load (copies/mL) | ||||||||

| ≤10ˆ5 | 75 | (10) | 1138 | (16) | 42 | (12) | 1255 | (15) |

| >10ˆ5 | 56 | (8) | 1177 | (16) | 67 | (19) | 1300 | (16) |

| Not tested | 612 | (82) | 4895 | (68) | 243 | (69) | 5750 | (69) |

| Median [IQR] | 62000 | [20303,264000] | 105 000 | [30 500,362 400] | 151 900 | [70 500,380 840] | 105000 | [30589,358000] |

| First ART regimen | ||||||||

| NRTI+NNRTI | 700 | (94) | 6618 | (92) | 313 | (89) | 7631 | (92) |

| NRTI+PI | 41 | (6) | 505 | (7) | 37 | (11) | 583 | (7) |

| Other | 2 | (0) | 87 | (1) | 2 | (1) | 91 | (1) |

| Previous mono/dual therapy | ||||||||

| No | 728 | (98) | 7061 | (98) | 329 | (93) | 8118 | (98) |

| Yes | 15 | (2) | 149 | (2) | 23 | (7) | 187 | (2) |

| Clinical Site | ||||||||

| Cambodia | 323 | (44) | 2115 | (29) | 97 | (28) | 2535 | (30) |

| Hong Kong | 14 | (2) | 704 | (10) | 76 | (22) | 794 | (10) |

| Indonesia | 114 | (15) | 954 | (13) | 29 | (8) | 1097 | (13) |

| Singapore | 222 | (30) | 1529 | (21) | 50 | (14) | 1801 | (22) |

| Vietnam | 33 | (4) | 1467 | (21) | 92 | (26) | 1592 | (19) |

| South Korea | 37 | (5) | 441 | (6) | 8 | (2) | 486 | (6) |

Cumulative LTFU and mortality rates

The median duration of follow-up was 34 months (IQR: 15-62 months). Of the 8 305 patients, 743 patients were LTFU over 26 217 person-years (pys), giving a crude LTFU rate of 2.83 (95% CI: 2.64-3.05) per 100 pys (Table 2). In addition, there were 352 deaths with a crude death rate of 1.34 (95% CI: 1.21-1.49) per 100 pys.

Table 2. Factors associated with permanent LTFU, defined as no clinic visit for 180 days, among all patients under follow-up.

| Events | / | pys | Rate per 100 pys (95% CI) | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| SHR | 95% CI | p value | SHR | 95% CI | p value | |||||

| 743 | / | 26217 | 2.83 (2.64, 3.05) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Year of ART Initiation | 0.595 | 0.746 | ||||||||

| 2003-2005 | 67 | / | 4531 | 1.48 (1.16, 1.88) | 0.74 | (0.57, 0.96) | 0.023 | 0.73 | (0.56, 0.95) | 0.021 |

| 2006-2009 | 396 | / | 12734 | 3.11 (2.82, 3.43) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2010-2013 | 280 | / | 8952 | 3.13 (2.78, 3.52) | 0.90 | (0.77, 1.07) | 0.231 | 0.83 | (0.69, 0.99) | 0.034 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Age at ART initiation (years) | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| ≤30 | 245 | / | 6694 | 3.66 (3.23, 4.15) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 31-40 | 255 | / | 10721 | 2.38 (2.10, 2.69) | 0.67 | (0.56, 0.80) | <0.001 | 0.67 | (0.56, 0.80) | <0.001 |

| 41-50 | 150 | / | 5548 | 2.70 (2.30, 3.17) | 0.73 | (0.59, 0.91) | 0.004 | 0.72 | (0.58, 0.89) | 0.002 |

| 51+ | 93 | / | 3254 | 2.86 (2.33, 3.50) | 0.71 | (0.55, 0.92) | 0.008 | 0.69 | (0.53, 0.90) | 0.007 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 503 | / | 18147 | 2.77 (2.54, 3.02) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Female | 240 | / | 8070 | 2.97 (2.62, 3.38) | 1.05 | (0.89, 1.25) | 0.546 | 1.13 | (0.94, 1.36) | 0.186 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mode of HIV Exposure | <0.001 | 0.005 | ||||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 503 | / | 18139 | 2.77 (2.54, 3.03) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Homosexual contact | 106 | / | 3893 | 2.72 (2.25, 3.29) | 1.21 | (0.95, 1.54) | 0.130 | 1.36 | (1.05, 1.76) | 0.021 |

| Injecting drug use | 65 | / | 1786 | 3.64 (2.85, 4.64) | 1.89 | (1.41, 2.55) | <0.001 | 1.65 | (1.19, 2.30) | 0.003 |

| Other/unknown | 69 | / | 2400 | 2.88 (2.27, 3.64) | 1.16 | (0.89, 1.52) | 0.269 | 1.11 | (0.85, 1.44) | 0.440 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Time-updated CD4 (cells/μL) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤50 | 117 | / | 1175 | 9.96 (8.31, 11.93) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 51-100 | 61 | / | 1098 | 5.56 (4.32, 7.14) | 0.60 | (0.43, 0.82) | 0.001 | 0.59 | (0.43, 0.82) | 0.001 |

| 101-200 | 144 | / | 3679 | 3.91 (3.32, 4.61) | 0.50 | (0.39, 0.65) | <0.001 | 0.48 | (0.37, 0.62) | <0.001 |

| 201+ | 369 | / | 16883 | 2.19 (1.97, 2.42) | 0.34 | (0.27, 0.44) | <0.001 | 0.32 | (0.25, 0.41) | <0.001 |

| Not tested | 52 | / | 3382 | 1.54 (1.17, 2.02) | 0.21 | (0.15, 0.30) | <0.001 | 0.19 | (0.14, 0.28) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Time-updated HIV viral load (copies/mL) | ||||||||||

| ≤100000 | 177 | / | 8500 | 2.08 (1.80, 2.41) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| >100000 | 14 | / | 462 | 3.03 (1.80, 5.12) | 0.83 | (0.47, 1.48) | 0.535 | 0.58 | (0.32, 1.05) | 0.072 |

| Not tested | 552 | / | 17256 | 3.20 (2.94, 3.48) | 0.96 | (0.78, 1.18) | 0.699 | 0.84 | (0.67, 1.04) | 0.114 |

|

| ||||||||||

| First ART regimen | 0.333 | 0.390 | ||||||||

| NRTI+NNRTI | 700 | / | 23879 | 2.93 (2.72, 3.16) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| NRTI+PI | 41 | / | 2127 | 1.93 (1.42, 2.62) | 1.01 | (0.70, 1.46) | 0.965 | 1.03 | (0.71, 1.49) | 0.873 |

| Other | 2 | / | 211 | 0.95 (0.24, 3.8) | 0.36 | (0.09, 1.40) | 0.140 | 0.38 | (0.10, 1.55) | 0.178 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hepatitis B co-infection | 0.170 | |||||||||

| Negative | 519 | / | 20693 | 2.51 (2.3, 2.73) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 59 | / | 2362 | 2.50 (1.94, 3.22) | 1.04 | (0.80, 1.37) | 0.755 | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.33) | 0.936 |

| Not tested | 165 | / | 3162 | 5.22 (4.48, 6.08) | 1.89 | (1.53, 2.34) | <0.001 | 1.43 | (0.99, 2.08) | 0.060 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hepatitis C co-infection | 0.002 | |||||||||

| Negative | 499 | / | 20472 | 2.44 (2.23, 2.66) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Positive | 73 | / | 2364 | 3.09 (2.46, 3.88) | 1.79 | (1.39, 2.31) | <0.001 | 1.54 | (1.16, 2.05) | 0.003 |

| Not tested | 171 | / | 3382 | 5.06 (4.35, 5.87) | 2.00 | (1.62, 2.46) | <0.001 | 1.50 | (1.04, 2.18) | 0.030 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Clinical Site | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Cambodia | 323 | / | 9706 | 3.33 (2.98, 3.71) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Hong Kong | 14 | / | 3110 | 0.45 (0.27, 0.76) | 0.14 | (0.08, 0.23) | <0.001 | 0.11 | (0.06, 0.20) | <0.001 |

| Indonesia | 114 | / | 3128 | 3.64 (3.03, 4.38) | 1.02 | (0.82, 1.27) | 0.848 | 0.53 | (0.40, 0.70) | <0.001 |

| Singapore | 222 | / | 5485 | 4.05 (3.55, 4.62) | 1.06 | (0.89, 1.27) | 0.480 | 1.00 | (0.78, 1.27) | 0.975 |

| Vietnam (Site 1) | 4 | / | 1533 | 0.26 (0.10, 0.70) | 0.06 | (0.02, 0.15) | <0.001 | 0.04 | (0.01, 0.11) | <0.001 |

| Vietnam (Site 2) | 29 | / | 1274 | 2.28 (1.58, 3.28) | 0.45 | (0.30, 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.29 | (0.18, 0.45) | <0.001 |

| South Korea | 37 | / | 1980 | 1.87 (1.35, 2.58) | 0.64 | (0.45, 0.90) | 0.009 | 0.56 | (0.35, 0.89) | 0.013 |

Global p-values are test for linear trend while all other global p-values are test for heterogeneity.

Note that global p-value test was not conducted if there were only two categories when using test for heterogeneity or three categories where one was ‘Not tested’ when using test for linear trend.

Multivariate model was adjusted for year of ART initiation, age at ART initiation, sex, mode of HIV exposure, time-updated CD4 count, time-updated HIV viral load, first ART regimen, hepatitis B co-infection, hepatitis C co-infection and clinical site.

NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

NNRTI = nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

PI = protease inhibitor.

Includes all other antiretroviral drug regimen combinations.

The cumulative LTFU incidence at 6, 12 and 24 months of follow-up for patients initiating ART: in 2003-05 was 1.5% (95% CI: 0.8-2.8%), 2.8% (95% CI: 1.7-4.4%) and 4.3% (95% CI: 2.9-6.1%); in 2006-09 was 2.9% (95% CI: 2.3-3.6%), 4.9% (95% CI: 4.2-5.8%) and 8.1% (95% CI: 7.1-9.2%); in 2010-13 was 2.1% (95% CI: 1.7-2.5%), 4.0% (95% CI: 3.4-4.6%) and 6.7% (95% CI: 5.9-7.5%), respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of LTFU and death across all countries, by year of ART initiation.

The cumulative mortality incidence at 6, 12 and 24 months of follow-up for patients initiating ART: in 2003-05 was 2.7% (95% CI: 1.6-4.2%), 4.3% (95% CI: 2.9-6.0%) and 6.2% (95% CI: 4.5-8.2%); in 2006-09 was 2.1% (95% CI: 1.6-2.8%), 2.6% (95% CI: 2.1-3.3) and 3.4% (95% CI: 2.8-4.1%); in 2010-13 was 2.0% (95% CI: 1.6-2.4%), 2.7% (95% CI: 2.3-3.3%) and 3.3% (95% CI: 2.8-3.9%), respectively (Figure 1).

The cumulative LTFU and mortality incidence has also been shown by country (Appendix 1). Three of the six countries displayed similar trends to the overall results, where the cumulative incidence of LTFU was high and mortality was low during 2006-09. However, the cumulative LTFU incidence reduction was less pronounced or even higher in 2010-13. Two of the six countries had consistent mortality and LTFU cumulative incidence during all time periods. One of the six countries only had data available for one time period (2010-13).

Factors associated with LTFU

The multivariate competing risks regression model, adjusted by clinical site, suggested that LTFU was associated with year of ART initiation, when adjusting for other relevant covariates (Table 2). Patients initiating in 2003-05 and 2010-13 had a subhazard ratio (SHR) of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.56-0.95; p value=0.021) and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.69-0.99; p value=0.034), respectively, compared to those initiating in 2006-09, adjusting for clinical site and other covariates.

Age at ART initiation was also significant in the multivariate model (p value=0.003), where those who were aged above 50 years were 31% less likely to be LTFU compared to those aged 30 or below (SHR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.53-0.90, p value=0.007). Patients with homosexual contact or injecting drug use as the mode of HIV exposure were 36% (SHR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.05-1.76, p value=0.021) and 65% (SHR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.19-2.30, p value=0.003) more likely to be LTFU compared to patients with heterosexual contact, respectively.

Patients with a higher current CD4 cell count were also less likely to be LTFU (p value <0.001). Those with a current CD4 count above 200 cells/μL were 67% less like to be LTFU compared to those with a current CD4 cell count ≤50 cells/μL (SHR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.25-0.41, p value<0.001). Patients ever having a positive HCV antibody test were 54% more likely to be LTFU than those that had never contracted HCV (SHR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.16-2.05, p value=0.003). Clinical site was significantly associated with LTFU in the multivariate model (p value <0.001). The two larger sites, Cambodia and Singapore, had a higher risk of LTFU compared to the other sites.

Discussion

Our findings have shown that the rate of LTFU has varied by year of ART initiation in this cohort of 8 305 HIV-positive patients receiving ART in Asia. The LTFU rate was lowest for those initiating in 2003-05, reaching 4.3% at 24 months of follow-up. The mortality rate was highest during this period of ART initiation, with a cumulative incidence of 6.2% at 24 months of follow-up. However, in 2006-09, there was a rapid increase in the LTFU rate to 8.1% at 24 months of follow-up while the mortality rate nearly halved to 3.4% at 24 months of follow-up. During 2010-13, the LTFU rate decreased compared to the previous period to 6.7% at 24 months of follow-up, while the mortality rate remained stable at 3.3% at 24 months of follow-up. The mortality rate surpassed LTFU rates only during the first 4 months of follow-up for those initiating ART in 2006-09 and 2010-13.

Since the UNAIDS initiative to scale-up universal access to ART, there has been a substantial increase in the expansion of services and HIV-positive people receiving ART in Asia as well as other regions 30-32. Significant improvements in the survival of patients receiving ART followed, likely as a result of a combination of factors including greater access to ART, earlier initiation of ART and, more tolerable and convenient ART regimens26. However, the rapid growth within the programs may also be accompanied by poorer patient retention and higher rates of LTFU33. There was some indication in our findings to suggest that sites with more patients tended to have higher LTFU rates than other sites. Recently, there has been greater attention on reducing LTFU rates to ensure patients are retained in care, maintain adherence and achieve better long term outcomes5,34. Treatment programmes in Asia commonly conduct at least one form of outreach and tracking for adults receiving ART who have missed clinic visits19. Most report phone call as the method of contact, but other methods include sending letters, home visits, consulting with pharmacies and checking hospital records. ART adherence support services, such as one-on-one counselling and reminder tools, are also offered at a vast majority of treatment programmes. Hence, increased support services and other resources at the site-level to engage patients in long-term care may have contributed to the decreasing LTFU seen in recent years35.

Similar trends have been reported in a multiregional analysis where the LTFU rate at 12 months after ART initiation increased from 9.3 per 100 pys (95% CI: 8.7-9.9) in 2004 to 14.6 per 100 pys (95% CI: 14.1-15.2) in 2010 36. Concurrently, the mortality rate at 12 months from ART initiation decreased from 11.8 per 100 pys (95% CI: 11.1-12.6) to 5.1 per 100 pys (95% CI: 4.8-5.4) in 2010. Other studies have reported a less prominent increase in LTFU rates after scale-up37. Our cumulative LTFU incidence ranged between 4.3-8.1% at 24 months, depending on year of ART initiation. This was relatively low compared to other HIV cohorts within the region which may be reflective of our ART programmes generally being better resourced tertiary referral sites. The LTFU incidence in India and China was 14% and 16%, at 24 months, for patients initiating ART in 2007-11 and 2005-10, respectively38,39. Outside of the region, in Rwanda, the cumulative LTFU rate for patients initiating ART in 2005-10 was low at 4.4% (95% CI: 4.4-4.5%) at 24 months. However, the cumulative mortality rate was nearly double our mortality rate at 6.3% (95% CI: 6.2-6.4%) 40. While in South Africa, both LTFU and mortality rates are much higher at 24 months, ranging from 13.4% (95% CI: 12.0-14.9%) to 26.5% (95% CI: 23.8-29.2%) and 7.4% (95% CI: 6.4-8.5%) to 15.4% (95% CI: 13.2-17.6%), respectively, for patients initiating in 2005-2010 at three different HIV programmes41.

Our findings also highlight that lower CD4 count is strongly associated with a greater risk of LTFU. Previous studies have also shown a similar association42-44. As LTFU patients have a high mortality rate, the lower CD4 count may reflect the association with mortality arising from unreported deaths rather than LTFU from a lack of engagement in care. It may also relate to suboptimal adherence, where those patients less engaged with care also have lower ART adherence, leading to lower CD4 counts and subsequently LTFU45,46.

The risk of LTFU was highest among those aged ≤30 years at ART initiation. This is consistent with Africa cohorts where retention in care is lowest among the ≤30 age group and highlights the need to engage adolescents and young adults47. In contrast with European and US HIV studies, we did not see greater retention in those aged >50 years at ART initiation48. Patients with HCV co-infection, homosexual contact or injecting drug use as the mode of HIV exposure were associated with a higher risk of LTFU. These populations are often marginalized and faced with stigma and discrimination, subsequently impacting on their engagement with health services49-52.

There were limitations to our study. Some patient data had large proportions of missing data, such as HIV viral load. Subsequently, the association with LTFU should not be over interpreted. In addition, while our study had a relatively large patient sample size, our data was obtained from seven clinical sites across six countries from Asia, where most countries had one contributing site. Hence, our analysis is not necessarily representative of trends occurring within the given country or the region. There is also the potential for site-level differences in the resources available that can dictate the level of patient care provided, the type of ART and other unmeasurable confounders that could influence the results. Disengagement from the clinic may be influenced by cultural or social factors that vary between the countries, such as stigma and discrimination53. Hence, it is difficult to make direct comparisons of LTFU between our clinical sites. However, we have adjusted for clinical site in the multivariate model, as well as providing figures by clinical site, to account for heterogeneity between the sites and produce more reliable estimates.

Another limitation is the bias arising from our chosen LTFU definition27. Previous studies have used definitions ranging from 90 days 7 to 365 days 54 with no clinic visit. We have attempted to minimize error in the determining patients LTFU by using validated definitions that achieve optimal specificity and sensitivity for LTFU, both in our own TAHOD cohort28 and supported by other studies55. Transient gaps between clinical visits can also introduce bias in identifying LTFU patients who have recently initiated ART. As patients who initiate ART recently have less time to return to care, they are more likely to be incorrectly classified as LTFU following a temporary interruption in care. However, this tends to overestimate LTFU rates in patients with recent ART initiation56. Therefore, our observed LTFU rates are likely to be conservative of the true LTFU rate and there is potentially a greater difference between the LTFU rates in 2006-09 and 2010-13.

Patient deaths were ascertained through hospital records and, in some cases, through further tracing to national death registries or verbal autopsy, but this was site dependent and practices may have varied over time. Hence, there is possible bias in the underreporting of deaths, where some patients may have been incorrectly classified as LTFU. In particular, the increasing number of patients presenting for care may have contributed to under-recording of deaths in recent years. However, our mortality rate was consistent between 2006-09 and 2010-13, and our observed LTFU rate could be overestimating the true LTFU and underestimating mortality rates.

In conclusion, we have shown that the LTFU rates in HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in our cohort have varied by the year of ART initiation. With an increasing number of patients initiating ART, the mortality rate in 2003-05 halved in subsequent years while the LTFU rate markedly increased. Those initiating in 2010-13 have reduced LTFU rates compared to 2006-09, while maintaining the same low mortality rate. Further increases in site-level resources to improve adherence counselling and support services would be needed to reduce LTFU and promote retention as HIV care increasingly transitions to a chronic disease management model35,57,58.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

TAHOD-LITE (TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database Low-Intensity TransfEr) is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a program of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Mental Health, and National Institute on Drug Abuse as part of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907). The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Australia (The University of New South Wales). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors do not have any competing interests to declare.

TAHOD-LITE study members: PS Ly and V Khol, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology & STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia;

MP Lee, PCK Li, W Lam and YT Chan, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China;

N Kumarasamy, S Saghayam and C Ezhilarasi, Chennai Antiviral Research and Treatment Clinical Research Site (CART CRS), YRGCARE Medical Centre, VHS, Chennai, India

TP Merati, DN Wirawan and F Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine Udayana University & Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia;

OT Ng, PL Lim, LS Lee and R Martinez-Vega, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore;

JY Choi, Na S and JM Kim, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea;

TT Pham, DD Cuong and HL Ha, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam;

KV Nguyen, HV Bui, DTH Nguyen and DT Nguyen, National Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, Vietnam;

AH Sohn, J Ross and B Petersen, TREAT Asia, amfAR - The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand;

NL De La Mata, A Jiamsakul, DC Boettiger and MG Law, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia, Sydney, Australia.

Authors' contributions: NLD and ML contributed to the concept development. PSL, OTN, KVN, TPM, TTP, MPL and JYC contributed data for the analysis. NLD performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented on the draft manuscript and approved of the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Brennan AT, Maskew M, Sanne I, Fox MP. The importance of clinic attendance in the first six months on antiretroviral treatment: a retrospective analysis at a large public sector HIV clinic in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makunde WH, Francis F, Mmbando BP, et al. Lost to follow up and clinical outcomes of HIV adult patients on antiretroviral therapy in care and treatment centres in Tanga City, north-eastern Tanzania. Tanzania journal of health research. 2012 Oct;14(4):250–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007-2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010 Jun;15(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalal RP, Macphail C, Mqhayi M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult patients lost to follow-up at an antiretroviral treatment clinic in johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Jan 1;47(1):101–107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b833a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Mar;53(3):405–411. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weigel R, Hochgesang M, Brinkhof MW, et al. Outcomes and associated risk factors of patients traced after being lost to follow-up from antiretroviral treatment in Lilongwe, Malawi. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu JK, Chen SC, Wang KY, et al. True outcomes for patients on antiretroviral therapy who are “lost to follow-up” in Malawi. Bull World Health Organ. 2007 Jul;85(7):550–554. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.037739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng EH, Glidden DV, Emenyonu N, et al. Tracking a sample of patients lost to follow-up has a major impact on understanding determinants of survival in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010 Jun;15(1):63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yiannoutsos CT, An MW, Frangakis CE, et al. Sampling-based approaches to improve estimation of mortality among patient dropouts: experience from a large PEPFAR-funded program in Western Kenya. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tweya H, Feldacker C, Estill J, et al. Are They Really Lost? “True” Status and Reasons for Treatment Discontinuation among HIV Infected Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy Considered Lost to Follow Up in Urban Malawi. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 26;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, et al. Highly active antiretroviral treatment as prevention of HIV transmission: review of scientific evidence and update. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010 Jul;5(4):298–304. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a6c32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonhoeffer S, Rembiszewski M, Ortiz GM, Nixon DF. Risks and benefits of structured antiretroviral drug therapy interruptions in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2000 Oct 20;14(15):2313–2322. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang DN, Hicks CB, Goswami ND, et al. Evolution of Drug-Resistant Viral Populations during Interruption of Antiretroviral Therapy. J Virol. 2011 Jul;85(13):6403–6415. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02389-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazdanpanah Y, Wolf LL, Anglaret X, et al. CD4+ T-cell-guided structured treatment interruptions of antiretroviral therapy in HIV disease: projecting beyond clinical trials. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(3):351–361. doi: 10.3851/IMP1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNairy ML, Ei-Sadr WM. The HIV care continuum: no partial credit given. AIDS. 2012 Sep 10;26(14):1735–1738. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328355d67b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conviser R, Pounds MB. The role of ancillary services in client-centred systems of care. AIDS Care. 2002 Aug;14(1):S119–131. doi: 10.1080/09540120220150018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duda SN, Farr AM, Lindegren ML, et al. Characteristics and comprehensiveness of adult HIV care and treatment programmes in Asia-Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas: results of a site assessment conducted by the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) Collaboration. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17:19045. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardner EM, Young B. The HIV care cascade through time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014 Jan;14(1):5–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70272-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. Ambitious Treatment Targets: Writing the final chapter of the AIDS epidemic. United Nations; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raymond A, Hill A, Pozniak A. Large disparities in HIV treatment cascades between eight European and high-income countries - analysis of break points. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014 Nov;17:13–14. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulle A, Ford N. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in developing countries: what are the benefits and challenges? Postgrad Med J. 2008 May;84(991):225–227. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.JointUnited Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) HIV in Asia and the Pacific: UNAIDS report 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, et al. The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database: baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Feb 1;38(2):174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000145351.96815.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De La Mata NL, Kumarasamy N, Khol V, et al. Improved survival in HIV treatment programmes in Asia. Antivir Ther. 2016 Mar 10; doi: 10.3851/IMP3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimsrud AT, Cornell M, Egger M, Boulle A, Myer L. Impact of definitions of loss to follow-up (LTFU) in antiretroviral therapy program evaluation: variation in the definition can have an appreciable impact on estimated proportions of LTFU. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013 Sep;66(9):1006–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J, Tanuma J, Chaiwarith R, et al. Loss to Followup in HIV-Infected Patients from Asia-Pacific Region: Results from TAHOD. AIDS research and treatment. 2012;2012:375217. doi: 10.1155/2012/375217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999 Jun;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srikantiah P, Ghidinelli M, Bachani D, et al. Scale-up of national antiretroviral therapy programs: progress and challenges in the Asia Pacific region. AIDS. 2010 Sep;24(3):S62–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390091.45435.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stringer JSA, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of Antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia - Feasibility and early outcomes. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2006 Aug 16;296(7):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organisation. Scaling up HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care: a report on WHO support to countries in implementing the “3 by 5” initiative 2004-2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assefa Y, Alebachew A, Lera M, Lynen L, Wouters E, Van Damme W. Scaling up antiretroviral treatment and improving patient retention in care: lessons from Ethiopia, 2005-2013. Globalization and health. 2014 May 27;10:43. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harding R, Krakauer EL, Sithole Z, De Lima L, Selman L. The ‘lost’ HIV population: time to refocus our clinical and research efforts. AIDS. 2009 Jan 2;23(1):145–146. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831de90b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamb MR, El-Sadr WM, Geng E, Nash D. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among ART patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimsrud A, Balkan S, Casas EC, et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral therapy over a 10-year period of expansion: a multicohort analysis of African and Asian HIV programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014 Oct 1;67(2):e55–66. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabapathy K, Ford N, Chan KN, et al. Treatment outcomes from the largest antiretroviral treatment program in Myanmar (Burma): a cohort analysis of retention after scale-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Jun 1;60(2):e53–62. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824d5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alvarez-Uria G, Naik PK, Pakam R, Midde M. Factors associated with attrition, mortality, and loss to follow up after antiretroviral therapy initiation: data from an HIV cohort study in India. Global health action. 2013;6:21682. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu H, Napravnik S, Eron J, et al. Attrition among Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Infected Patients Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy in China, 2003-2010. PLoS One. 2012 Jun 27;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mugisha V, Teasdale CA, Wang C, et al. Determinants of mortality and loss to follow-up among adults enrolled in HIV care services in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wandeler G, Keiser O, Pfeiffer K, et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment programs in rural Southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Feb 1;59(2):e9–16. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823edb6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ford N, Kranzer K, Hilderbrand K, et al. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy and associated reduction in mortality, morbidity and defaulting in a nurse-managed, community cohort in Lesotho. AIDS. 2010 Nov 13;24(17):2645–2650. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ec5b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clouse K, Pettifor A, Maskew M, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy when presenting with higher CD4 cell counts results in reduced loss to follow-up in a resource-limited setting. AIDS. 2013 Feb 20;27(4):645–650. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835c12f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabillard D, Lewden C, Ndoye I, et al. Mortality, AIDS-morbidity, and loss to follow-up by current CD4 cell count among HIV-1-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Africa and Asia: data from the ANRS 12222 collaboration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Apr 15;62(5):555–561. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182821821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox MP, Shearer K, Maskew M, et al. Treatment outcomes after 7 years of public-sector HIV treatment. AIDS. 2012 Sep 10;26(14):1823–1828. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357058a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalal RP, MacPhail C, Mqhayi M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult patients lost to follow-up at an antiretroviral treatment clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Jaids-J Acq Imm Def. 2008 Jan 1;47(1):101–107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b833a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vinikoor MJ, Joseph J, Mwale J, et al. Age at Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation Predicts Immune Recovery, Death, and Loss to Follow-Up Among HIV-Infected Adults in Urban Zambia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014 Oct 1;30(10):949–955. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Korthuis PT, Gebo KA, Network HIVR. Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Jul 1;60(3):249–259. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318258c696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang F, Zhu H, Wu Y, et al. HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus co-infection in patients in the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program, 2010-12: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014 Nov;14(11):1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70946-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolfe D. Paradoxes in antiretroviral treatment for injecting drug users: access, adherence and structural barriers in Asia and the former Soviet Union. Int J Drug Policy. 2007 Aug;18(4):246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maher L, Coupland H, Musson R. Scaling up HIV treatment, care and support for injecting drug users in Vietnam. Int J Drug Policy. 2007 Aug;18(4):296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greifinger R, Batchelor M, Fair C. Improving engagement and retention in Adult care settings for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) youth living with HIV: Recommendations for health care providers. 2013;17(1):80–95. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vu VT, Pharris A, Thorson A, Alfven T, Larsson M. It is not that I forget, it's just that I don't want other people to know”: barriers to and strategies for adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV patients in Northern Vietnam. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2011;23(2):139–145. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006 Mar 11;367(9513):817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med. 2011 Oct;8(10):e1001111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson LF, Estill J, Keiser O, et al. Do Increasing Rates of Loss to Follow-up in Antiretroviral Treatment Programs Imply Deteriorating Patient Retention? Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Dec 15;180(12):1208–1212. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chung MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic outcomes. PLoS Med. 2011 Mar;8(3):e1000422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rachlis B, Ahmad F, van Lettow M, Muula AS, Semba M, Cole DC. Using concept mapping to explore why patients become lost to follow up from an antiretroviral therapy program in the Zomba District of Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013 Jun 11;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.