Case Report

A 40-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a 3-month history of asthenia, wasting, polyarthralgia, and bleeding gums. In the previous 24 hours he had multiple episodes of hematochezia without hemodynamic instability. His past medical history included alcoholism (120 g of ethanol per day for approximately one decade) and an unbalanced diet without any fresh vegetables or fruits.

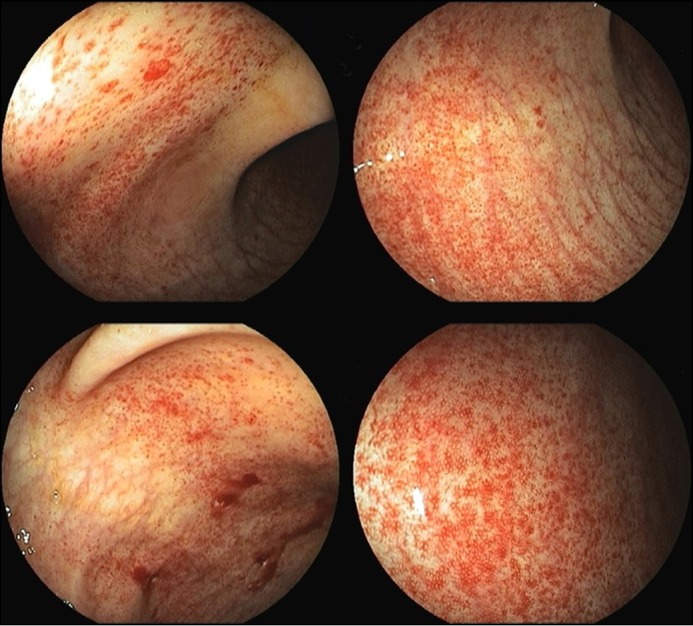

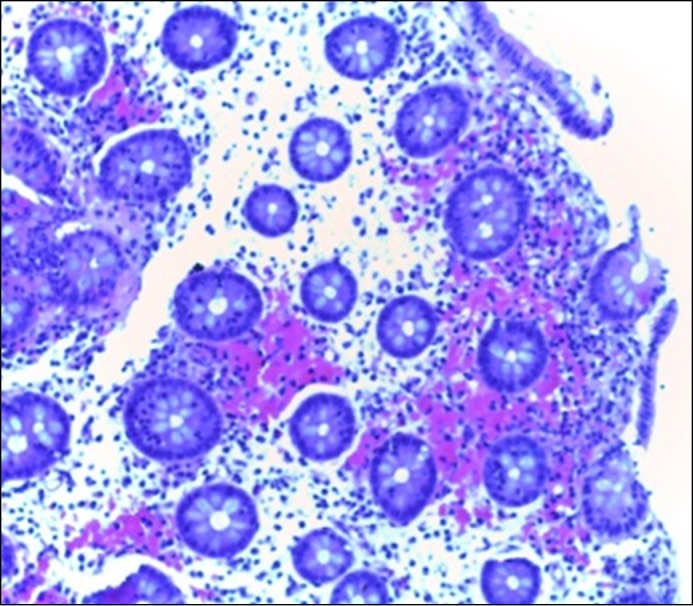

On physical examination, his conjunctivae were pale, and he had severe periodontitis with gingival hypertrophy and purplish areas consistent with necrosis (Figure 1). His skin revealed follicular hyperkeratosis, and his legs were hairless (Figure 2). Laboratory blood tests showed hemoglobin 7.1 g/L, mean corpuscular volume 104.7 f/L, white blood cell count 11.4 x 109/L, platelets 89 x 109/L, international normalized ratio 1.83, total bilirubin 3.5 mg/dL, albumin 2.9 g/dL, creatinine 0.89 mg/dL, magnesium 1.1 mg/dL, calcium 7.7 mg/dL, phosphorus 2.0 mg/dL, ferritin 10 ng/mL, transferrin 56 mg/dL, vitamin B9 2.1 ng/mL, vitamin B12 582 pg/mL, and vitamin C 0.14 mg/dL. Colonoscopy showed multiple intramucosal hemorrhages in the cecum and ascending colon (Figure 3). Histological examination revealed mild infiltration by inflammatory cells and hemorrhagic areas in the lamina propria (Figure 4). Upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies showed no abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasound indicated cirrhosis and revealed mild ascites. Subsequent investigations were negative, and we assumed an alcohol-related liver disease (Child-Pugh 10 points, model end-stage liver disease score 18 points). Portal hypertensive colopathy as the cause for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding was excluded, given the absence of its classical signs (fibromuscular proliferation in lamina propria, congested capillaries, and irregular thickening of their wall).

Figure 1.

Periodontitis with gingival hypertrophy.

Figure 2.

Follicular hyperkeratosis and hairless legs.

Figure 3.

Intramucosal hemorrhages in the cecum and ascending colon.

Figure 4.

Cecum biopsies revealing mild infiltration of inflammatory cells and focal hemorrhage in the lamina propia.

We assumed the diagnosis of scurvy and initiated oral vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 100 mg 3 times per day for 2 weeks, followed by 100 mg per day for one month) and adequate nutrition. Systemic symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding disappeared in the first week, followed by resolution of hyperkeratosis and gingival abnormalities in the first month. Two months after admission, the patient presented complete clinical recovery without anemia (hemoglobin 13.1 g/L) and with normal serum vitamin C values (1.6 mg/dL).

Scurvy is caused by ascorbic acid deficiency. In the Western world, almost all cases occur in elderly people, alcoholics, psychiatric and institutionalized patients, and people participating in fad diets or those with malabsorption disorders.1,2 Ascorbic acid is essential to the stabilization of the collagen triple-helix structure. Its deficiency results in the loss of blood vessel integrity and leads to bleeding risk.3 The spectrum of clinical presentation and the fact that our patient had a severe vitamin C deficiency were the hallmarks for the diagnosis of scurvy. The histology was similar to cases described in previous reports of scurvy presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding, resolving promptly after replacement therapy with vitamin C.1,4,5

Disclosures

Author contributions: AS Gião Antunes wrote the manuscript and is the article guarantor. B. Peixe designed the study and acquired the data. H. Guerreiro drafted the manuscript.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

References

- 1.Schuman RW, Rahmin M, Dannenberg AJ. Scurvy and the gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997; 45:195–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosdol A, Erens B, Brunner EJ. Estimated prevalence and predictors of vitamin C deficiency within UK's low-income population. J Public Health (Oxf). 2008; 30:456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyera N, Galey I, Bernard BA. Effect of vitamin C and its derivatives on collagen synthesis and cross-linking by normal human fibroblasts. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1998; 20(3):151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohta A, Yoshida S, Imaeda H, et al. Scurvy with gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2013; 45(Suppl 2 UCTN):E147–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer WC, Vazquez-Roche M. Scurvy presenting as hematochezia. Endoscopy. 2014; 46(Suppl 1):E292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]