Abstract

The changes for oropharyngeal lesions in the 2017 edition of the WHO/IARC Classification of Head and Neck Tumours reference book are dramatic and significant, largely due to the growing impact of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV). The upcoming edition divides tumours of the oral cavity and oropharynx into separate chapters, classifies squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) of the oropharynx on the basis of HPV status, abandons the practice of histologic grading for oropharyngeal SCCs that are HPV positive, recognizes small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, and combines polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma and cribriform adenocarcinoma of tongue and minor salivary glands under the single term “polymorphous adenocarcinoma.” This review not only calls attention to these changes, but describes the rationale driving these changes and highlights their implications for routine clinical practice.

Keywords: World Health Organization, Oropharynx, Squamous cell carcinoma, Human papillomavirus, Small cell carcinoma, Polymorphous adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Periodic updates of the WHO/IARC Classification of Tumours reference books (i.e. Blue Books) permit intermittent refinements of tumor taxonomy based on an ever advancing state of science. By and large, changes tend to be minor and reflect some trifling parlance among organ-specific pathology experts, or the description of some newly recognized boutique tumor entities. In effect, modifications from one edition to the next may have little practical relevance for the general surgical pathologist or the oncology community at large. Truly meaningful changes usually occur over extended periods of time and across multiple editions of the Blue Books. If that is the rule, then the upcoming edition to the WHO’s classification of oropharyngeal cancer is a notable exception. The chapter on oropharyngeal carcinoma highlights a profound transformation that has shaken the head and neck oncology landscape in ways that are having a widespread impact on the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognostication of head and neck cancer. Prior to the new edition, a chapter dedicated exclusively to the oropharynx as anatomic site separate from the oral cavity proper did not exist, and a distinctive form of oropharyngeal SCC related to the human papillomavirus (HPV) was not yet recognized. This review will highlight the guidelines proposed by the WHO to aid the diagnostic pathologist in the recognition, designation, and reporting of the HPV-positive form of oropharyngeal SCC and will draw attention to other important, if less momentous, changes made in the new edition.

Separation of Oropharyngeal and Oral Cavity Tumours

Anatomically, the oral cavity proper is comprised of the lips, gingiva, retromolar trigone, hard palate, buccal mucosa, mobile tongue, and floor of the mouth, whereas the oropharynx is comprised of the palatine tonsils, soft palate, tongue base (posterior to the circumvallate papillae), and posterior pharyngeal wall. Although the oral cavity and oropharynx form one continuous chamber lined by an uninterrupted stratified squamous epithelium, and by historical convention have been lumped together under the blanket term “oral” or “oral cancer”, they are dissimilar in many important respects. Most notable is the presence of tonsillar tissue (i.e. lingual and palatine tonsils) in the oropharynx, and its absence in the oral cavity. The highly specialized lymphoepithelium (i.e. reticulated epithelium) lining the tonsillar crypts provides a more permissive environment for HPV infection and HPV-driven tumorigenesis [1], resulting in much higher rates of HPV in SCCs of the oropharynx (OPSCC) than in SCCs of the oral cavity.

More precise tumor classification as a function of anatomic subsite is helpful in identifying and explaining epidemiologic trends and interpreting clinical trials. Reflecting the rising burden of HPV-positive cancer, recent analyses of cancer registry data show dramatic increases in incidence of oropharyngeal carcinomas during the past 15–20 years in several parts of the world, even as the incidence of oral cavity carcinomas has remained constant or declined during the same period [2]. As for clinical research, careful attention to tumor site and HPV status when designing studies and interpreting data facilitates meaningful comparison of treatment responses for patients enrolled in these trials. In effect, persistent disregard for the anatomical, histological, ultrastructural, and immunological differences between the oral cavity and oropharynx may have masked important differences in incidence trends and clinical outcomes. This distinction had been appropriately recognized in the 7th edition of the American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC) staging manual which separately staged oral cavity and oropharyngeal carcinomas. The just released new 8th edition will also now separately stage HPV-driven (p16 positive) and HPV-negative (p16 negative) OPSCCs. To further remedy this longstanding shortcoming, the 2017 edition of the Blue Book appropriately partitions carcinomas of the oral “vault” into tumours of the oral cavity and oropharynx.

New Terminology for Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Oropharynx

SCC of the head and neck has long been regarded as a monotonous tumor entity. Important distinctions including anatomic site have largely been ignored given the uniformity of histopathology and response to treatment. However, since the release of the 2005 edition of the Blue Book over a decade ago, a body of work has underscored important differences in a subgroup of SCC of the head and neck (HNSCCs) that go well beyond variations related to tumor site and stage. In particular, a subset characterized by origin in the oropharynx and the presence of transcriptionally-active HPV stands apart as a pathologically and clinically unique form of HNSCC. These HPV-positive OPSCCs have unique demographic profiles, unique genetic features distinct from typical HNSCCs [3], clinical [4], feature distinct morphologic features [5, 6], and have improved clinical outcomes [7]. In effect, recognition of this HPV association amounts to nothing less than the identification of a distinct tumor entity.

Acknowledging that not all HNSCCs are the same, the new Blue Book has adopted a classification scheme that separates OPSCCs as a function of HPV status. For OPSCCs that are found to be HPV positive, the term “squamous cell carcinoma, HPV-positive” is recommended for its simplicity, clarity, and directness. Conversely, the term “squamous cell carcinoma, HPV negative” is recommended for those tumours that are HPV negative. These diagnostic categories should only be used for SCCs of oropharyngeal origin as the significance of finding HPV in non-oropharyngeal sites is much less clear. While the WHO underscores the importance of direct HPV testing (e.g. in situ hybridization and/or PCR based assays), it also allows for indirect testing using p16 immunohistochemical staining as a reliable surrogate marker of HPV status. OPSCCs that are HPV positive have diffuse p16 expression (nuclear and cytoplasmic), something those that are HPV negative typically lack.

The Morphology of HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinomas

In those situations where p16 or direct HPV testing is not available, the 2017 edition of the Blue Book recommends “squamous cell carcinoma, HPV not tested, morphology highly suggestive of HPV association” for those OPSCCs showing the typical microscopic features associated with HPV infection. Use of this designation by practicing pathologists obviously requires some familiarity with this distinctive morphologic profile.

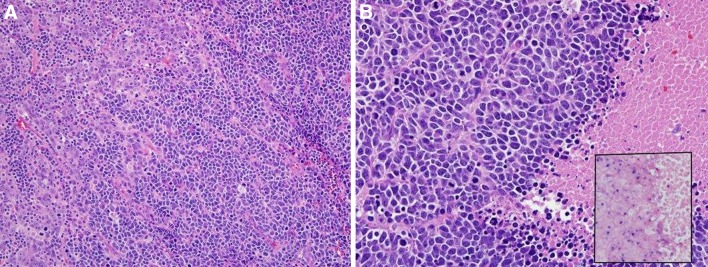

HPV-positive OPSCCs consistently arise from the tonsillar crypts. In contrast to HPV-negative OPSCCs, they are not associated with keratinizing dysplasia of the surface epithelium. Most HPV-positive OPSCCs have a distinct, nonkeratinizing morphology (Figs. 1, 2) [5, 8, 9]. Nonkeratinizing SCCs typically consist of large, pushing-bordered nests of tumor cells with little or no discernible stromal reaction. They are embedded in the dense lymphoid stroma of the tonsillar tissue and have cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and round to oval nuclei which are usually hyperchromatic with inconspicuous nucleoli, brisk mitotic activity with frequent apoptosis, and necrosis. In areas, the tumor cells will become spindled with fusiform nuclei. Maturing squamous differentiation is usually absent or is limited in extent (Fig. 3) [10]. The emerging definition for nonkeratinizing SCC is that, if it has maturing squamous differentiation, that it is present in less than 10% of the overall tumor surface area [5]. Using this definition, ~50–55% of all OPSCCs and ~70% of all HPV-positive OPSCCs are nonkeratinizing [5].

Fig. 1.

The right side of this tonsillar crypt is colonized by an HPV-positive squamous cell carcinoma. The carcinoma retains many of the features of the crypt epithelium, making it very difficult to distinguish neoplastic from non-neoplastic epithelium by routine H&E staining (a). A p16 immunohistochemical stain is helpful in confirming the presence and distribution of the HPV-positive squamous cell carcinoma (b)

Fig. 2.

Most HPV-related squamous cell carcinomas have a nonkeratinizing morphology with tumor in large nests with smooth edges and little stromal reaction (a). Tumor cells have little cytoplasm and have round to oval to spindled nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and brisk mitotic activity (b). In this tumor, there is no maturing squamous differentiation. HPV human papillomavirus

Fig. 3.

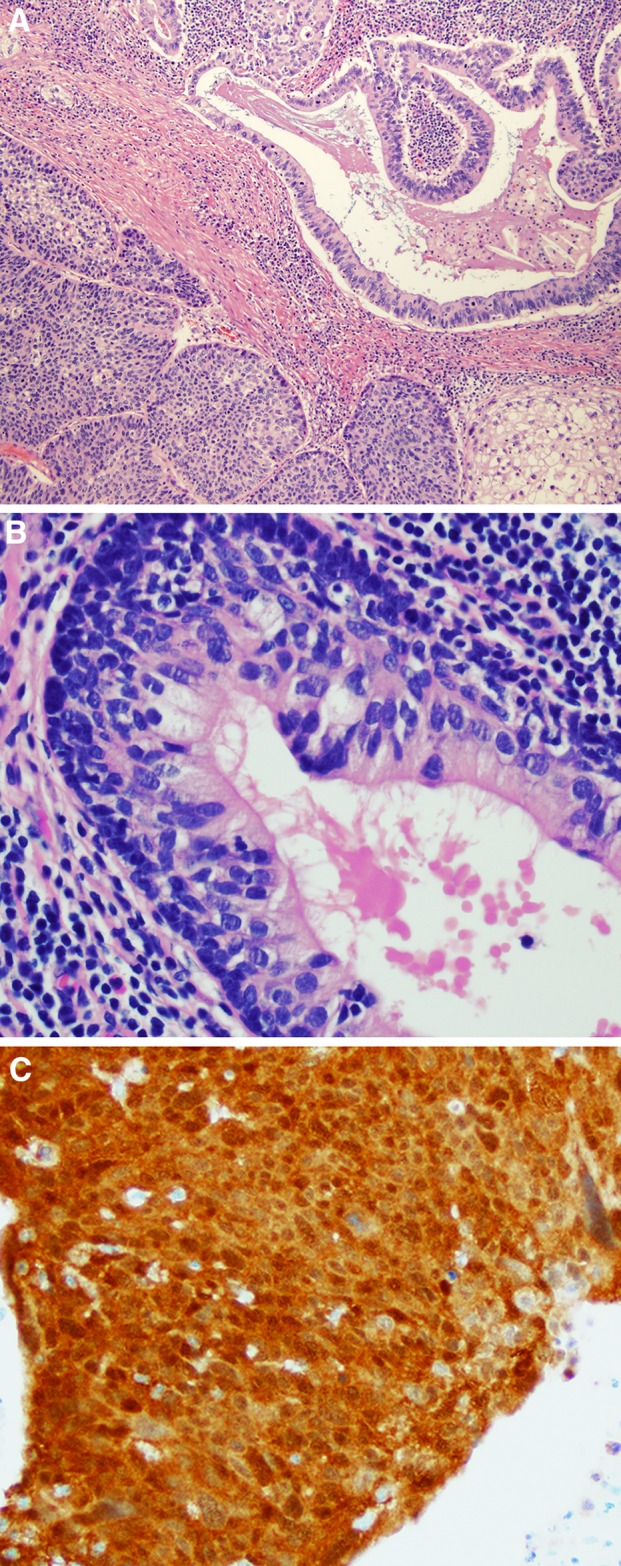

Adenosquamous carcinoma showing well-formed glands with rounded, “punched out” luminal spaces, focal globular basophilic and eosinophilic mucin, and a surrounding component of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (a). Rare cases of adenosquamous carcinoma are ciliated, with tumor cells with terminal bars and apical cilia (b). The tumor cells of both of these were strongly diffusely positive for p16, a surrogate marker of high risk HPV (c)

The morphologic spectrum of HPV-positive OPSCC includes basaloid and papillary SCC, adenosquamous (Fig. 3), lymphoepithelial (undifferentiated), and sarcomatoid (or spindle cell) carcinomas. It also includes, as recently described in small patient series, the presence of ciliated tumor cells “ciliated adenosquamous carcinoma”. Although the number of reported cases of these variant forms is limited, the best available data suggests that patients with transcriptionally-active HPV have clinical outcomes that are similar to HPV-positive OPSCC with typical morphology [11–21].

Histologic Grading of HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Largely based on the immature, non-keratinized and basaloid appearance of its tumor cells, HPV-positive OPSCCs are widely perceived as poorly or undifferentiated. Indeed, numerous studies have uniformly reported a strong and direct correlation between HPV positivity and a “high” histologic grade [22]. The grading of HPV-positive OPSCCs, however, may be flawed since grading schemes reflexively adopt the stratified squamous epithelium lining the external surface of the tonsil as its point of reference for gauging morphologic divergence. In reality, HPV-positive OPSCCs usually arise from the reticulated epithelium lining the tonsillar crypts, and they consistently retain the basaloid and non-keratinizing appearance of this specialized epithelium (Fig. 1) [6]. In effect, HPV-positive OPSCC may well be better regarded as highly differentiated carcinomas despite their immature appearance and lack of keratin production. Dispelling the notion that HPV-positive OPSCCs are poorly or undifferentiated carcinomas helps establish these tumours as crypt (not surface)-derived, and disentangles the perplexing epidemiologic trend of improving patient survival in the face of “worsening” tumor grade for patients with OPSCC [23].

Studies have yet to identify and verify histopathologic parameters that are useful in recognizing the smaller subgroup of HPV-positive OPSCC associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes. Until appropriate histologic correlates are established, the 2017 edition breaks with time honored practices by discouraging histologic grading of HPV-positive OPSCCs.

Small Cell Carcinoma

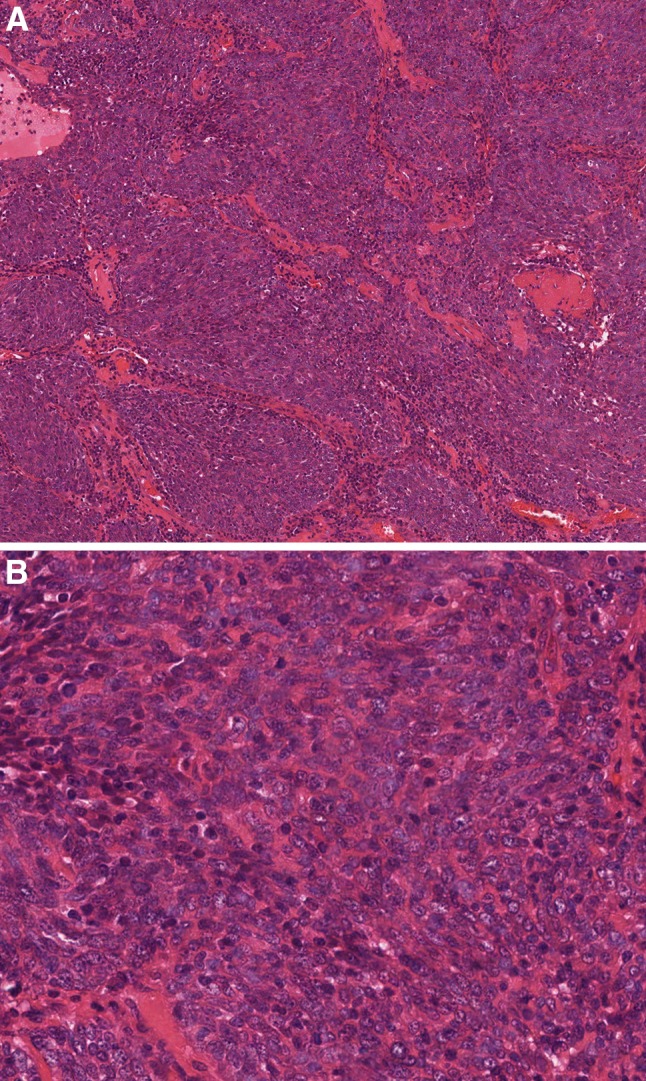

Small cell carcinoma is a very rare form of head and neck cancer. Most small cell carcinomas of the head and neck occur in the larynx, and its description in the oropharynx is limited to a case reports and small case series. Its inclusion in the 2017 edition to the WHO’s classification of oropharyngeal carcinomas reflects a concern that small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx may be on the rise. It is well documented that HPV-positive OPSCCs can undergo small cell transformation (Fig. 4) [24, 25]. In one series, 80% of the cases arose in association with a synchronous or metachronous HPV-positive OPSCC [24]. Accordingly, the rising overall incidence of HPV-positive carcinomas may be driving a parallel upsurge in the appearance of its various subtypes including small cell carcinoma. Retrospective studies have noted the striking absence of HPV in small cell carcinomas of the head and neck prior to 2000 [24]. Thus, an HPV-positive form of small cell carcinoma would not have been readily appreciated at the writing of the 2005 edition of the Blue Book.

Fig. 4.

Some small cell carcinomas of the oropharynx represent HPV-positive squamous cell carcinomas (a, upper left) that have undergone small cell transformation (a, right). Like small cell carcinoma of the lung and other sites, oropharyngeal small cell carcinomas are comprised of small anaplastic cells with a high mitotic rate and necrosis (b). HPV is retained in the small cell component (inset, high risk HPV DNA in situ hybridization) but the finding of HPV may be of little if any prognostic significance

Like small cell carcinomas of the lung, these HPV-positive small cell carcinomas of the oropharynx are associated with cigarette smoking, high grade cellular features, expression of neuroendocrine markers, and an aggressive clinical behavior including widespread dissemination and poor survival [24–26]. This aggressive clinical behavior is in sharp contrast to non-small cell carcinomas of the oropharynx where the presence of HPV is associated with highly favorable survival rates. Given this considerable divergence in clinical behavior, the 2017 edition of the Blue Book both acknowledges small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, and sets it apart as a distinct entity rather than just another variant form of HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma.

Salivary Gland Tumours

There are no minor salivary gland tumours that are unique to the oropharynx, but some do occur with enough regularity at this site to warrant consideration in this section. Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) has a strong predilection for the minor salivary glands of the hard and soft palates. PLGA is characterized by cellular uniformity, architectural diversity, and an infiltrative growth pattern including perineural invasion [27, 28] (Fig. 5). As highlighted by the “low grade” designation adopted in past editions of the Blue Book, PLGA tends to behave in a non-aggressive fashion. Even though 10–33% of patients develop local recurrences and as many as 9–15% develop nodal metastases [24], PLGA does not metastasize to distant sites or cause patient death. In rare instances, however, PLGA may transform into a highly malignant tumor characterized by high grade morphologic features and more aggressive clinical behavior [29–31]. To accommodate this definite albeit rare phenomenon known as high grade transformation [32], the 2017 edition of the Blue Book has abandoned the qualifier “low grade”, and now designates these tumours simply as polymorphous adenocarcinomas. This modification helps avoid potential confounding terminology (e.g. “high grade polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma”) and facilitates grade-appropriate therapy for those exceptional cases showing high grade transformation.

Fig. 5.

Polymorphous adenocarcinoma incorporates both the classic, low grade tumor (a) characterized by a nodular, but unencapsulated low power appearance, with tumor cells in cords, tubules, and cribriform nests with a blue-gray stroma. On high power (b), the tumor consists of cells with oval nuclei that are bland and isomorphic. The cribriform variant shows more extensive cribriform growth (c) and nests with spaces around them giving a “glomeruloid” appearance. The individual tumor cells (d) are round to oval with irregular contours and fine chromatin, mimicking papillary thyroid carcinoma

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands (CAMSG) is a salivary gland carcinoma that often arises in the tongue and especially the tongue base [33, 34]. CAMSG is similar and yet subtly different form PLGA. First, both tumours exhibit cellular uniformity and infiltrative growth, but CAMSGs are more likely to exhibit a cribriform or “glomeruloid” pattern of growth (Fig. 5). Second, both PLGA and CAMSG activate the PRKD gene family, but by different mechanisms (i.e. point mutations in the PRKD1 gene and genomic rearrangements of the PRKD family, respectively). Third, both tumours are relatively indolent, but CAMSG is more likely to metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Currently it is not known whether this behavioral variance reflects innate biologic differences or simply the increased likelihood of CAMSG to involve the posterior (base of) tongue—a site rich in lymphatics and more permissive to regional spread. The continued reluctance on the part of the WHO to include CAMSG in the section on oropharyngeal tumours reflects, in part, the broader decision to incorporate CAMSG within the polymorphous adenocarcinoma family until their discriminating features are sufficiently sharp to warrant separation as distinct tumor entities.

Conclusion

The new edition of the WHO Blue Book has arrived with great anticipation. Much has changed in head and neck pathology in the past 10–12 years, including a great deal in oropharyngeal tumours. With the alarming upsurge of HPV-positive OPSCC, the WHO has responded by creating a separate oropharynx chapter and separating OPSCCs on the basis of HPV status. Oropharyngeal small cell carcinomas can be HPV-positive and must be distinguished from SCC since they appear to be aggressive tumours, regardless of HPV status. Finally, the WHO has specified that polymorphous adenocarcinoma be the blanket term for tumours formerly designated as PLGA or CAMSG.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Neither author has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Special Issue: World Health Organization Classification Update

References

- 1.Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, Taube JM, Westra WH, Akpeng B, et al. Evidence for a role of the PD-1:PD-L1 pathway in immune resistance of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(6):1733–1741. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK. Epidemiology and clinical aspects of HPV in head and neck cancers. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S16–S24. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes DN, Van Waes C, Seiwert TY. Genetic landscape of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer and comparison to tobacco-related tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3227–3234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3235–3242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gondim DD, Haynes W, Wang X, Chernock RD, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS Jr. Histologic typing in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A 4-year prospective practice study with p16 and high-risk HPV mRNA testing correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Westra WH. The changing face of head and neck cancer in the 21st century: the impact of HPV on the epidemiology and pathology of oral cancer. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(1):78–81. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0100-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Mofty SK, Patil S. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma: characterization of a distinct phenotype. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westra WH. The morphologic profile of HPV-related head and neck squamous carcinoma: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S48–S54. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernock RD. Morphologic features of conventional squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: ‘keratinizing’ and ‘nonkeratinizing’ histologic types as the basis for a consistent classification system. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S41–S47. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0373-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begum S, Westra WH. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is a mixed variant that can be further resolved by HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(7):1044–1050. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816380ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chernock RD, Lewis JS, Jr, Zhang Q, El-Mofty SK. Human papillomavirus-positive basaloid squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular subtype of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2010;41(7):1016–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jo VY, Mills SE, Stoler MH, Stelow EB. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: frequent association with human papillomavirus infection and invasive carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(11):1720–1724. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b6d8e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singhi AD, Stelow EB, Mills SE, Westra WH. Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma of the oropharynx: a morphologic variant of HPV-related head and neck carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(6):800–805. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9ba21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop JA, Montgomery EA, Westra WH. Use of p40 and p63 immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus testing as ancillary tools for the recognition of head and neck sarcomatoid carcinoma and its distinction from benign and malignant mesenchymal processes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):257–264. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter DH, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS., Jr Undifferentiated carcinoma of the oropharynx: a human papillomavirus-associated tumor with a favorable prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(10):1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masand RP, El-Mofty SK, Ma XJ, Luo Y, Flanagan JJ, Lewis JS., Jr Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: relationship to human papillomavirus and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5(2):108–116. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehrad M, Carpenter DH, Chernock RD, Wang H, Ma XJ, Luo Y, et al. Papillary Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: Clinicopathologic and Molecular Features With Special Reference to Human Papillomavirus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Watson RF, Chernock RD, Wang X, Liu W, Ma XJ, Luo Y, et al. Spindle cell carcinomas of the head and neck rarely harbor transcriptionally-active human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(3):250–257. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop JA, Westra WH. Ciliated HPV-related Carcinoma: A Well-differentiated Form of Head and Neck Carcinoma That Can Be Mistaken for a Benign Cyst. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(11):1591–1595. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radkay-Gonzalez L, Faquin W, McHugh JB, Lewis JS, Jr, Tuluc M, Seethala RR. Ciliated adenosquamous carcinoma: expanding the phenotypic diversity of human papillomavirus-associated tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(2):167–175. doi: 10.1007/s12105-015-0653-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendelsohn AH, Lai CK, Shintaku IP, Elashoff DA, Dubinett SM, Abemayor E, et al. Histopathologic findings of HPV and p16 positive HNSCC. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(9):1788–1794. doi: 10.1002/lary.21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta V, Yu GP, Schantz SP. Population-based analysis of oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: changing trends of histopathologic differentiation, survival and patient demographics. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(11):2203–2212. doi: 10.1002/lary.21129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop JA, Westra WH. Human papillomavirus-related small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1679–1684. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182299cde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraft S, Faquin WC, Krane JF. HPV-associated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the oropharynx: a rare new entity with potentially aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(3):321–330. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823f2f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bates T, McQueen A, Iqbal MS, Kelly C, Robinson M. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the oropharynx harbouring oncogenic HPV-infection. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8(1):127–131. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castle JT, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, Wenig BM, Kessler HP. Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 164 cases. Cancer. 1999;86(2):207–219. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990715)86:2<207::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elhakim MT, Breinholt H, Godballe C, Andersen LJ, Primdahl H, Kristensen CA, et al. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: a danish national study. Oral Oncol. 2016;55:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloreta J, Serrano S, Corominas JM, Ferres-Padro E. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma arising in the nasal cavities with an associated undifferentiated carcinoma. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19(5):365–370. doi: 10.3109/01913129509021908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simpson RH, Pereira EM, Ribeiro AC, Abdulkadir A, Reis-Filho JS. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands with transformation to high-grade carcinoma. Histopathology. 2002;41(3):250–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelkey TJ, Mills SE. Histologic transformation of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of salivary gland. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111(6):785–791. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/111.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagao T. “Dedifferentiation” and high-grade transformation in salivary gland carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(Suppl 1):S37–S47. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michal M, Skalova A, Simpson RH, Raslan WF, Curik R, Leivo I, et al. Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue: a hitherto unrecognized type of adenocarcinoma characteristically occurring in the tongue. Histopathology. 1999;35(6):495–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skalova A, Sima R, Kaspirkova-Nemcova J, Simpson RH, Elmberger G, Leivo I, et al. Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland origin principally affecting the tongue: characterization of new entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(8):1168–1176. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821e1f54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]