Abstract

AIM

To analyze the anatomy of sacral venous plexus flow, the causes of injuries and the methods for controlling presacral hemorrhage during surgery for rectal cancer.

METHODS

A review of the databases MEDLINE® and Embase™ was conducted, and relevant scientific articles published between January 1960 and June 2016 were examined. The anatomy of the sacrum and its venous plexus, as well as the factors that influence bleeding, the causes of this complication, and its surgical management were defined.

RESULTS

This is a review of 58 published articles on presacral venous plexus injury during the mobilization of the rectum and on techniques used to treat presacral venous bleeding. Due to the lack of cases published in the literature, there is no consensus on which is the best technique to use if there is presacral bleeding during mobilization in surgery for rectal cancer. This review may provide a tool to help surgeons make decisions regarding how to resolve this serious complication.

CONCLUSION

A series of alternative treatments are described; however, a conventional systematic review in which optimal treatment is identified could not be performed because few cases were analyzed in most publications.

Keywords: Presacral hemorrhaging, Rectal surgery, Sacral venous plexus, Pelvic surgery, Sacral anatomy

Core tip: This is a review of 58 published articles on presacral venous plexus injury during the mobilization of the rectum and on techniques used to treat presacral venous bleeding. We believe that this work is potentially relevant to helping surgeons understand the physiopathology of this complication and making them aware of possible surgical strategies for its treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Presacral venous plexus injury during the mobilization of the rectum is one of the most frequent intra-operative complications during rectal cancer surgery[1]. With an incidence that ranges from 0.25% to 8.6%[2,3], it can cause rapid hemodynamic instability in the patient and can even be lethal[4]. The presacral venous plexus cannot be visualized by the surgeon, and injury to the presacral fascia or avulsion of the rectosacral fascia from its insertion into the sacral periosteum can injure the presacral and basivertebral veins, causing bleeding that is difficult to manage with conventional hemostatic maneuvers. Accordingly, a series of techniques that offer alternatives to traditional hemostatic methods for the treatment of presacral venous bleeding have been described. This review aimed to analyze the anatomy of the sacral venous plexus (SVP), the factors influencing the incidence of presacral venous plexus injury, and the flow of bleeding in an effort to classify the available treatment techniques and make surgeons aware of possible strategies for the management of this complication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The databases MEDLINE®, PubMed®, and Embase™ were searched for manuscripts published between January 1960 and June 2016 using the following keywords: presacral bleeding, presacral hemorrhage, pelvic surgery, rectal surgery, presacral venous plexus, presacral anatomy, and pelvic packing. The reference lists from the articles were reviewed to identify additional pertinent articles. This review includes 58 articles on the anatomical vascular data of the SVP, the essential factors that influence the flow of bleeding after venous injury, the causes and types of injury, the incidence of presacral bleeding, and treatments applied to control this bleeding in rectal cancer surgery. Due to the limited number of cases reported in most publications and the variety of procedures used to control this complication, conventional systematic review and meta-analysis could not be performed.

RESULTS

Anatomical considerations

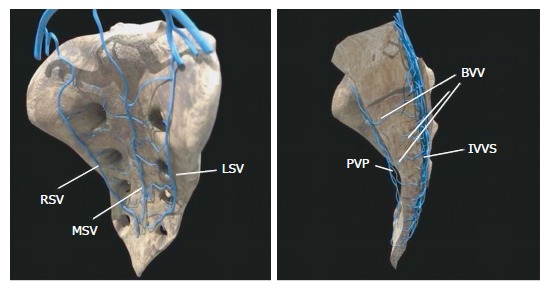

The vascular anatomy of the SVP is complex and includes a wide and intricate network of veins primarily formed by the anastomosis between the medial and lateral sacral veins. The medial sacral vein usually drains into the left common iliac vein, whereas the lateral veins drain into the internal iliac vein. The SVP receives contributions from the lumbar veins of the posterior abdominal wall and the basivertebral veins that pass through the sacral foramen. Morphological studies of human sacral bones show that 100% of the specimens feature foramina that communicate with the anterior sacral face and the cancellous bone of the vertebral bodies. Between 16% and 22% of these foramina are 2 to 5 mm in diameter, are located on the anterior face of S4-S5, and are penetrated by the basivertebral veins originating in the cancellous bone, which measures between 0.7 mm and 1.5 mm in this region[4,5] (Figure 1). The small basivertebral veins, which are very thin, allow the bidirectional passage of blood because they lack valves; these veins flow in long, tortuous channels through the spongy tissue of the vertebral bodies. The lateral sacral veins, the medial sacral vein, and the basivertebral veins constitute a wide network of anastomoses that form the venous plexus on the anterior sacral surface[4,6] (Figure 2). The medial sacral vein can be located to the left or the right of the midline and is duplicated in 80% of cases[7]. The vascular anastomoses between the medial sacral vein and the lateral veins are often less than 3 cm from the sacral promontory; specifically, this distance is 2 cm in 90% of cases, and the anastomosis is located at the level of the 3rd and 4th sacral foramen in 70% of cases[6,7]. The retrosacral fascia, also called Waldeyer's fascia, has been described as a sheet of connective tissue that extends from the periosteum of the sacrum to the posterior wall of the rectum approximately 3-4 cm above the anorectal junction. Anatomical and radiological studies have revealed that although its insertion into the sacrum can occur between the 1st coccygeal vertebra and S2, it is located at the level of S3 and S4 in 84%-94% of cases[8-11], just where the foramen that give rise to the basivertebral veins are thickest.

Figure 1.

Sacrum specimen. Multiple sacral basivertebral vein foramin, between 2-4 mm, are seen on S4-S5.

Figure 2.

Diagram showing the sacral venous system. RSV: Right sacral vein; LSV: Left sacral vein; MSV: Middle sacral vein; PVP: Presacral venous plexus; IVVS: Internal vertebral venous system; BVV: Basivertebral vein.

Hydrodynamic studies

The essential factors that influence the flow of blood from an injured vein are the size of the vein and the intravenous pressure at the broken point of the vein. Hydrostatic pressure in the SVP depends on the following: the pressure of the inferior vena cava, the distance from S4-S5 to the coronal axis of the inferior vena cava traced from the renal veins to the iliac bifurcation, and the elevated pressure on the inferior vena cava due to the lithotomy position. Experimental studies and the application of general hydrodynamic principles suggest that the hydrostatic pressure in the sacral plexus in the lithotomy position is approximately twice the venous pressure of the inferior vena cava in the supine decubitus position, and injury to a vein with diameter between 0.5 mm and 4 mm can cause blood flow of 32 mL/min to 1994 mL/min[4,5].

Causes types of injury

Although the height of the tumor in the rectum, the infiltration of the presacral fascia by the tumor, the use of adjuvant radiotherapy, prior rectal surgery, and poor visualization of the surgical field have been described as risk factors that influence the incidence of presacral bleeding during rectal resection, the most common cause is the anatomical relationship of the anorectal fascia. The fascia and its surrounding tissues, including the presacral veins, can be lacerated by the surgeon due to inadequate dissection of the posterior wall of the rectum in the sacral concavity. This maneuver can be caused instrumentally and, more frequently, by blunt dissection by the fingers of the surgeon. The average distance between the ventral surface of the sacrum and the mesorectum is 12 mm or 13 mm as measured by magnetic resonance (MR) and computed tomography (CT), respectively[12]. Laceration of the presacral fascia due to dissection of the sacrum very close to the surface and lifting of this fascia with or without the periosteum are other common causes of presacral bleeding[3,4,13-15].

Wang et al[4] describe 3 types of venous injury and direct implications for their handling: injury to the presacral veins (type I), injury to the presacral veins and/or basivertebral veins of diameter < 2 mm (type II), and injury to the presacral veins and/or basivertebral veins of diameter > 2 mm (type III).

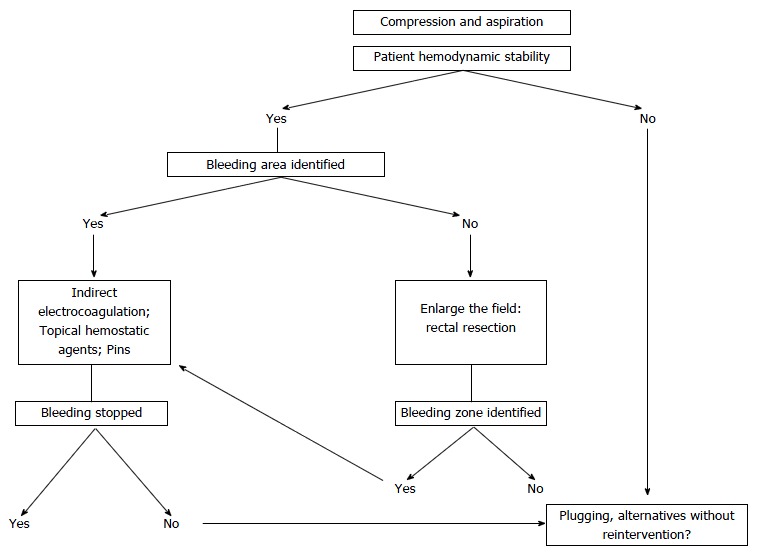

Surgical management

In addition to the application of temporary direct pressure on the bleeding area as the first maneuver, various methods have been employed to treat this complication. Ligature of the internal iliac artery is not effective and can cause gluteal and vesical necrosis[16], and ligation of the internal iliac vein makes venous drainage of its tributaries difficult, increases pressure on the sacral plexus, and exacerbates bleeding[4,16-18]. Similarly, Celentano et al[19] we propose a classification of techniques (Table 1) and an algorithm for the management of sacral venous bleeding (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Classification of techniques for the control of presacral bleeding

| Pelvic plugging | |

| Traditional with compresses | |

| Sengstaken-Blakemore tube | |

| Linton balloon | |

| Compartmental hemostatic balloon | |

| IV Saline Bag | |

| Breast implant | |

| Plugging with rectus abdominis muscle | |

| Plugging with Bonewax® | |

| Plugging with bone cement | |

| Bakri balloon | |

| Metal implants | |

| Simple pins | |

| Helical titanium pins + Surgicel® | |

| Staples + cancellous bone + Surgicel® | |

| Ligaclips® | |

| Topical hemostatic agents | |

| Cyanoacrylate | |

| Cyanoacrylate + Surgicel® | |

| Ankaferd Blood Stopper® | |

| Floseal® + Surgicel® | |

| Direct suture | |

| Infrarenal aorta clamp + PVS suture | |

| Suture-circular ligature | |

| Direct/indirect electrocoagulation | |

| Spray electrocautery | |

| Bipolar coagulation | |

| Argon coagulation | |

| Electrocoagulation on a piece of epiploic appendix/muscle fragment |

Figure 3.

Presacral venous hemorrhaging: treatment algorithm.

Pelvic plugging

Traditional plugging with compresses has been demonstrated to be effective[20], and surgeons should be familiar with this procedure because it may be the only successful mechanism to control potentially fatal bleeding[21]. After abdominoperineal resection, plugging can be performed through the abdomen following closure of the perineum or entirely via the perineum. In this case, explantation will require one or more additional laparotomies, and if the perineal route is used, re-bleeding after the explantation will complicate hemostatic maneuvers. The risk of re-bleeding, the increase in infection, the predisposition to dehiscence if the plug is placed adjacent to an anastomosis, and longer hospital admission are the main disadvantages of this procedure[2,14,20,22-24].

Alternatives to classic plugging that attempt to avoid re-intervention have been described, such as the use of an expandable pelvic prosthesis[25] or the use of the Sengstaken-Blakemore probe[26]. Holman et al[27] developed a model hemostatic balloon using MR images of the pelvis. After testing in cadavers, the balloons were used to treat 9 patients with presacral venous bleeding and produced good results in 89% of patients. Ng et al[28] describe an alternative to classic plugging after abdominoperineal resection using an empty IV bag filled with 850 mL of saline inserted through the perineum. The advantages of this technique include its adaptability to the sacral concavity and the ease of modifying the hemostatic pressure by infusing or withdrawing fluid through the infusion port. Moreover, the bag can be withdrawn through the perineal wound without requiring additional surgery. After failed attempts at hemostasis with classic plugging and metal implants, some authors[29] successfully used plugging, applying traction with a breast implant that was inflated with 520 mL of saline solution placed in the presacral space and maintaining pressure on the SVP using the traction of the implant, which was connected to a 1-L bag of saline suspended at the end of the bed. Remzi et al[30] recommend plugging with a free graft of the rectus abdominis muscle measuring 4 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm sutured to the presacral tissue over the area of bleeding. The absence of necrosis and lack of abscesses with this technique are attributed to the hypervascularization of the presacral area and the revascularization of the graft. Civelek et al[31] applied bone wax (Bonewax®) directly to the presacral fascia and the periosteum and simultaneously used pelvic plugging. After the failure of classic pelvic plugging and metal implants, Becker et al[32] recommend plugging the bleeding area directly with bone cement (polymethyl methacrylate). Moreover, the Bakri balloon, created specifically to be introduced into the uterine cavity to control bleeding[33], has been successfully used in 2 patients for the treatment of presacral bleeding after colorectal surgery[34].

Metal implants

Wang et al[4] first used pins in 1985 to control presacral bleeding. Since then, their implementation has been the subject of multiple communications, most of which reported good results[35-40]. However, pin placement can be technically difficult[22,37], especially in narrow pelvises[41], when the contour of the sacrum is not sufficiently smooth and regular or when osteoporotic disease is present in the bone[29,42]. Failure of the technique[14,32,41,43], development of a presacral hematoma, chronic pelvic pain, release, migration, and perianal extrusion of the implant[42], and the need for equipment that is not always routinely available in surgery[14,24] are complications and inconveniences associated with the implementation of this procedure. Its ineffectiveness for diffuse bleeding[44] has led to the development of other alternatives. Some authors[13,45] use the ProTack™ device to fix hemostatic sponges (Surgicel®) to the sacrum using helical titanium tacks. Wang et al[43] used saw-tooth staples of different sizes that fit into the gap between the staple and the sacrum, along with a spongy bone graft and a plate of Surgicel®. Jivapaisarnpong[46] reported the cessation of bleeding using vascular clips (Ligaclips®) in 3 patients in whom several other techniques, such as electrocauterization, coagulation with argon, indirect coagulation, and pelvic plugging, had failed.

Topical hemostatic agents

Topical hemostatic agents have been widely used, especially in cases of diffuse bleeding or when other methods have failed. For example, cyanoacrylate is a monomer that is purified by removing toxic products during its synthesis. Its contact with anionic substances such as blood causes it to polymerize into long chains that form a solid layer, resulting in hemostasis[47].

Losanoff et al[48] achieved hemostasis in 3 patients by evenly applying cyanoacrylate glue to the surface of a gelatin sponge measuring 3 cm × 2 cm; the sponge was then compressed for several minutes to ensure adequate contact with the presacral fascia and polymerization of the adhesive. Chen et al[49] used a combination of oxidized cellulose and cyanoacrylate. Specifically, they placed 2 to 5 pieces of 2 cm × 2 cm oxidized cellulose in a Kelly clamp and applied pressure to the injury for a few minutes. They then evenly applied 1 mL of cyanoacrylate to the cellulose surface and to the tissue surrounding the pieces of oxidized cellulose. Zhang et al[50] reported the control of bleeding in 5 patients by the application of pressure to the bleeding area with absorbable hemostatic gauze for 20-30 min. This gauze was similar to collagen and was created from cellulose that had been chemically treated and combined with alpha-cyanoacrylate as an adhesive. Karaman et al[51] achieved excellent results with the use of topical Ankaferd Blood Stopper® (ABS). ABS exhibits antihemorrhagic properties and is an extract of 5 medicinal plants that exert antithrombotic, antiplatelet, antioxidant, antiatherosclerotic, and antitumoral activities. Germanos et al[14] suggest that after several techniques have been tried and failed, presacral bleeding should be treated with direct hemostatic agents. Specifically, they used a gel formed by combining gelatin and thrombin (Floseal®) granules and an absorbable hemostatic agent, Surgicel®, prepared by the controlled oxidation of regenerated cellulose.

Direct suture

Some authors[14] report that clotting and direct suture are ineffective and should be avoided because they can exacerbate bleeding and cause significant blood loss[14]. Alternatively, Papalambros et al[52] report the potential benefits of temporarily clamping the infrarenal aorta, which hypothetically decreases blood flow in the vena cava and its tributaries and should reduce the hydrostatic pressure in the sacral plexus and bleeding. This approach would allow the identification of the point of bleeding and its suture. This procedure could be effective for treatment of type I injuries described by Wang et al[4], which are easiest to treat and can be addressed with less bloody methods. However, in the opinion of other authors[23], this approach would be difficult to apply successfully to injuries of the basivertebral veins after retraction in the sacral periosteum. Ligature and circular suturing were described by Jiang et al[53] in 2013 as a method to control presacral venous bleeding. Once the bleeding points have been identified, the venous plexus is ligated and circularly sutured with 4/0 silk. The suture includes the presacral fascia, the presacral veins, and the deep connective tissue. Bleeding that continues after the first suture suggests that the blood originates from the communicating veins or the basivertebral veins, which necessitates a second or even a third suture. However, if bleeding originates from veins retracted in the bone, Jiang et al[53] recommend the implementation of a combination of techniques as more efficient than the use of a single method for the control of bleeding in this situation.

Direct or indirect electrocoagulation

Filippakis et al[54] controlled bleeding in 4 patients using electrocauterization in the spraying position at the bleeding points of the presacral fascia. Furthermore, Li et al[55] proposed direct bipolar coagulation as a simple and effective method for the management of presacral venous bleeding after demonstrating the cessation of this type of bleeding in 7 patients. Kandeel et al[56] and Saurabh et al[57] reported 1 and 2 patients, respectively, in whom bleeding was controlled using argon coagulation.

Indirect monopolar electrocoagulation has been successfully used on a portion of an epiploic appendix by maintaining pressure on the bleeding area with a dissection clip[2,3]. Moreover, indirect electrocoagulation through a fragment of the anterior rectus abdominis muscle was described by Xu et al[58] and applied with success in 11 patients. The technique involves resecting a fragment of the anterior rectus abdominis muscle approximately 2 cm × 2 cm, placing it in a long dissection clip, applying pressure to the area of bleeding, and applying a monopolar current to induce clotting. Muscle is a soft tissue that contains approximately 75% water and is easily moldable to the bone surface. Water is an excellent conductor of energy due to the solutes dissolved in it. Thus, the implementation of electrocoagulation in muscle results in surgical smoke when the muscle is heated, and the cellular fluid is vaporized by the thermal action of the energy source. The temperature of the muscle gradually increases and reaches the boiling point after 90-120 s of application of monopolar current at maximum power. This temperature is the optimal coagulation point and ensures that the muscle adheres to the bone surface[23,58]. This method has been validated and used by other authors[22-24] with satisfactory results, in some cases after the failure of other alternatives. Specifically, it is a rapid, easily executed, and effective method that is usually free of intra- or post-operative complications and that can be used at several bleeding points. Furthermore, if the muscle does not adhere to the bone, the technique does not fail.

CONCLUSION

Sacral foramina that connect the internal venous plexus with the presacral venous plexus via the basivertebral veins are found at the levels of all vertebral bodies, and foramina of greater caliber are located at the level of S4-S5. Therefore, injury at that level presumably causes bleeding with greater flow that is difficult to control. The treatment algorithm we propose is based on the analysis of more than 50 articles presented in this review. This information can help the surgeon understand the physiopathology of and treatment strategies for presacral venous bleeding.

In our opinion and based on our experience with the occurrence of presacral bleeding during rectal surgery, indirect coagulation through the interposition of a fragment of the anterior rectus abdominis muscle is a very effective method when it is possible to identify the site of bleeding[23]. Other methods that have also proven effective are the use of topical hemostatic agents and the use of pins.

COMMENTS

Background

Presacral venous bleeding is a rare but potentially lethal complication of surgery for rectal cancer. Incorrect mobilization of the rectum that injures the presacral fascia or de-insertion of the anorectal fascia can cause bleeding in the sacral venous plexus. This bleeding can be very difficult to control at the level of the last sacral vertebrae due to injury to the large basivertebral veins.

Research frontiers

The present study aims to help surgeons understand the vascular anatomy of the presacral plexus, the pathophysiology of presacral bleeding, the factors influencing the flow of venous injury, the causes and types of damage, the incidence of presacral bleeding and the surgical strategies for treatment.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Due to the lack of cases published in the literature, there is no consensus on which is the best technique to use if there is presacral bleeding during mobilization in surgery for rectal cancer. This review may provide a tool to help surgeons make decisions regarding how to resolve this serious complication.

Applications

This review aims to provide a set of resources to resolve presacral bleeding.

Peer-review

This review will be helping surgeons understand the physiopathology of presacral bleeding and the surgical strategies for its treatment. It is really helpful.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 23, 2016

First decision: January 10, 2017

Article in press: February 17, 2017

P- Reviewer: Lin JM, Lopez V, Luchini C, Wang GY S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

References

- 1.Pollard CW, Nivatvongs S, Rojanasakul A, Ilstrup DM. Carcinoma of the rectum. Profiles of intraoperative and early postoperative complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:866–874. doi: 10.1007/BF02052590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lou Z, Zhang W, Meng RG, Fu CG. Massive presacral bleeding during rectal surgery: from anatomy to clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4039–4044. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i25.4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Ambra L, Berti S, Bonfante P, Bianchi C, Gianquinto D, Falco E. Hemostatic step-by-step procedure to control presacral bleeding during laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. World J Surg. 2009;33:812–815. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9846-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang QY, Shi WJ, Zhao YR, Zhou WQ, He ZR. New concepts in severe presacral hemorrhage during proctectomy. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1013–1020. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390330025005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casal Nuñez JE, García Martinez MT, Ruano Poblador A, Sánchez Conde JA, Pampín Medela JL, Moncada Iribarren E, De Sanildefonso Pereira A. [Presacral haemorrhage during rectal cancer resection: morphological and hydrodynamic considerations] Cir Esp. 2012;90:243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wieslander CK, Rahn DD, McIntire DD, Marinis SI, Wai CY, Schaffer JI, Corton MM. Vascular anatomy of the presacral space in unembalmed female cadavers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1736–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baqué P, Karimdjee B, Iannelli A, Benizri E, Rahili A, Benchimol D, Bernard JL, Sejor E, Bailleux S, de Peretti F, et al. Anatomy of the presacral venous plexus: implications for rectal surgery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26:355–358. doi: 10.1007/s00276-004-0258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato K, Sato T. The vascular and neuronal composition of the lateral ligament of the rectum and the rectosacral fascia. Surg Radiol Anat. 1991;13:17–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01623135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Armengol J, García-Botello S, Martinez-Soriano F, Roig JV, Lledó S. Review of the anatomic concepts in relation to the retrorectal space and endopelvic fascia: Waldeyer's fascia and the rectosacral fascia. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:298–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crapp AR, Cuthbertson AM. William Waldeyer and the rectosacral fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;138:252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown G, Kirkham A, Williams GT, Bourne M, Radcliffe AG, Sayman J, Newell R, Sinnatamby C, Heald RJ. High-resolution MRI of the anatomy important in total mesorectal excision of the rectum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:431–439. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan PS, Day TF, Albert TJ, Morrison WB, Pimenta L, Cragg A, Weinstein M. Anatomy of the percutaneous presacral space for a novel fusion technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:237–241. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000187979.22668.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Vurst TJ, Bodegom ME, Rakic S. Tamponade of presacral hemorrhage with hemostatic sponges fixed to the sacrum with endoscopic helical tackers: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1550–1553. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germanos S, Bolanis I, Saedon M, Baratsis S. Control of presacral venous bleeding during rectal surgery. Am J Surg. 2010;200:e33–e35. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomacruz RS, Bristow RE, Montz FJ. Management of pelvic hemorrhage. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:925–948. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.BINDER SS, MITCHELL GA. The control of intractable pelvic hemorrhage by ligation of the hypogastric artery. South Med J. 1960;53:837–843. doi: 10.1097/00007611-196007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hata M, Kawahara N, Tomita K. Influence of ligation of the internal iliac veins on the venous plexuses around the sacrum. J Orthop Sci. 1998;3:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s007760050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPartland KJ, Hyman NH. Damage control: what is its role in colorectal surgery? Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:981–986. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000075206.70623.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celentano V, Ausobsky JR, Vowden P. Surgical management of presacral bleeding. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:261–265. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13814021679951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zama N, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Lavery IC, Weakley FL, Church JM. Efficacy of pelvic packing in maintaining hemostasis after rectal excision for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:923–928. doi: 10.1007/BF02554887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirese E, Larciprete G. Emergency pelvic packing to control intraoperative bleeding after a Piver type-3 procedure. An unusual way to control gynaecological hemorrhage. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24:99–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayuste E, Roxas MF. Validating the use of rectus muscle fragment welding to control presacral bleeding during rectal mobilization. Asian J Surg. 2004;27:18–21. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casal Núñez JE, Martínez MT, Poblador AR. Electrocoagulation on a fragment of anterior abdominal rectal muscle for the control of presacral bleeding during rectal resection. Cir Esp. 2012;90:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison JL, Hooks VH, Pearl RK, Cheape JD, Lawrence MA, Orsay CP, Abcarian H. Muscle fragment welding for control of massive presacral bleeding during rectal mobilization: a review of eight cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1115–1117. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosman BC, Lackides GA, Fisher DP, Eskenazi LB. Use of tissue expander for tamponade of presacral hemorrhage. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:723–726. doi: 10.1007/BF02054419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCourtney JS, Hussain N, Mackenzie I. Balloon tamponade for control of massive presacral haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1996;83:222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holman FA, van der Pant N, de Hingh IH, Martijnse I, Jakimowicz J, Rutten HJ, Goossens RH. Development and clinical implementation of a hemostatic balloon device for rectal cancer surgery. Surg Innov. 2014;21:297–302. doi: 10.1177/1553350613507145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng X, Chiou W, Chang S. Controlling a presacral hemorrhage by using a saline bag: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:972–974. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braley SC, Schneider PD, Bold RJ, Goodnight JE, Khatri VP. Controlled tamponade of severe presacral venous hemorrhage: use of a breast implant sizer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:140–142. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remzi FH, Oncel M, Fazio VW. Muscle tamponade to control presacral venous bleeding: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1109–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Civelek A, Yeğen C, Aktan AO. The use of bonewax to control massive presacral bleeding. Surg Today. 2002;32:944–945. doi: 10.1007/s005950200189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker A, Koltun L, Shulman C, Sayfan J. Bone cement for control of massive presacral bleeding. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:409–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez-Lopez V, Abrisqueta J, Lujan J, Ferreras D, Parrilla P. Treatment of presacral bleeding after colorectal surgery with Bakri balloon. Cir Esp. 2016;94:303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nivatvongs S, Fang DT. The use of thumbtacks to stop massive presacral hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:589–590. doi: 10.1007/BF02554267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patsner B, Orr JW. Intractable venous sacral hemorrhage: use of stainless steel thumbtacks to obtain hemostasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:452. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90405-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmons MC, Kohler MF, Addison WA. Thumbtack use for control of presacral bleeding, with description of an instrument for thumbtack application. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnaud JP, Tuech JJ, Pessaux P. Management of presacral venous bleeding with the use of thumbtacks. Dig Surg. 2000;17:651–652. doi: 10.1159/000051981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harma M, Harma M. The use of thumbtacks to stop severe presacral bleeding: a simple, effective, readily available and potentially life-saving technique. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:466; author reply 466–447; discussion 467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar S, Malhotra N, Chumber S, Gupta P, Aruna J, Roy KK, Sharma JB. Control of presacral venous bleeding, using thumbtacks. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276:385–386. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suh M, Shaikh JR, Dixon AM, Smialek JE. Failure of thumbtacks used in control of presacral hemorrhage. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1992;13:324–325. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacerda-Filho A, Duraes L, Santos HF. Displacement and per-anal extrusion of a hemostatic sacral thumbtack: report of case. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2004;10:319–322. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang LT, Feng CC, Wu CC, Hsiao CW, Weng PW, Jao SW. The use of table fixation staples to control massive presacral hemorrhage: a successful alternative treatment. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:159–161. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181972242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stolfi VM, Milsom JW, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Church JM, Fazio VW. Newly designed occluder pin for presacral hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:166–169. doi: 10.1007/BF02050673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nasralla D, Lucarotti M. An innovative method for controlling presacral bleeding. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95:375–376. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13629960046877e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jivapaisarnpong P. The use of ligating clips (Liga Clips®) to control massive presacral venous bleeding: case reports. Thai J Surg. 2009;30:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer AJ, Quinn JV, Hollander JE. The cyanoacrylate topical skin adhesives. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Cyanoacrylate adhesive in management of severe presacral bleeding. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1118–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, Chen F, Xie P, Qiu P, Zhou J, Deng Y. Combined oxidized cellulose and cyanoacrylate glue in the management of severe presacral bleeding. Surg Today. 2009;39:1016–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang CH, Song XM, He YL, Han F, Wang L, Xu JB, Chen CQ, Cai SR, Zhan WH. Use of absorbable hemostatic gauze with medical adhesive is effective for achieving hemostasis in presacral hemorrhage. Am J Surg. 2012;203:e5–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karaman K, Bostanci EB, Ercan M, Kurt M, Teke Z, Reyhan E, Akoglu M. Topical Ankaferd application to presacral bleeding due to total mesorectal excision in rectal carcinoma. J Invest Surg. 2010;23:175. doi: 10.3109/08941930903564134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papalambros E, Sigala F, Felekouras E, Prassas E, Giannopoulos A, Aessopos A, Bastounis E, Hepp W. Management of massive presacral bleeding during low pelvic surgery -- an alternative technique. Zentralbl Chir. 2005;130:267–269. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-836528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang J, Li X, Wang Y, Qu H, Jin Z, Dai Y. Circular suture ligation of presacral venous plexus to control presacral venous bleeding during rectal mobilization. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:416–420. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Filippakis GM, Leandros M, Albanopoulos K, Genetzakis M, Lagoudianakis E, Pararas N, Konstandoulakis MM. The use of spray electrocautery to control presacral bleeding: a report of four cases. Am Surg. 2007;73:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li YY, Chen Y, Xu HC, Wang D, Liang ZQ. A new strategy for managing presacral venous hemorrhage: bipolar coagulation hemostasis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:3486–3488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kandeel A, Meguid A, Hawasli A. Controlling difficult pelvic bleeding with argon beam coagulator during laparoscopic ultra low anterior resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:e21–e23. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182054f13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saurabh S, Strobos EH, Patankar S, Zinkin L, Kassir A, Snyder M. The argon beam coagulator: a more effective and expeditious way to address presacral bleeding. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:73–76. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J, Lin J. Control of presacral hemorrhage with electrocautery through a muscle fragment pressed on the bleeding vein. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:351–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]