Abstract

Introduction

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive imaging method that enables the evaluation of pigmented and non-pigmented skin lesions. More recently, dermoscopy has been recognized as an effective tool in the diagnosis of nail diseases.

Aim

To evaluate the dermoscopic features of nail psoriasis and to assess the relationship between these features and disease severity.

Material and methods

A total of 67 patients with clinically evident nail psoriasis (14 women, 53 men) were prospectively enrolled. Following a thorough clinical examination, patients were graded according to the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index and physician’s global assessment score. A dermoscopic examination of all fingernails and toenails was performed using a videodermatoscope. Mann-Whitney U and χ2 tests were used for statistical analysis, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

Results

The most frequently observed dermoscopic features were splinter haemorrhage (73.1%), pitting (58.2%), distal onycholysis (55.2%), dilated hyponychial capillaries (35.8%) and the pseudo-fiber sign (34.3%). The pseudo-fiber sign, dilated hyponychial capillaries, nail plate thickening and crumbling, subungual hyperkeratosis, transverse grooves, trachyonychia, pitting and salmon patches were positively associated with disease severity.

Conclusions

The pseudo-fiber sign described in this study appears to be a novel dermoscopic feature of nail psoriasis. We have demonstrated positive associations between a number of dermoscopic manifestations and disease severity. Further studies are required to support the present findings.

Keywords: psoriasis, nail, dermoscopy, pseudo-fiber sign, severity

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic immune-mediated dermatosis seen worldwide. This condition affects both genders equally and tends to have a bimodal distribution in the age of onset, with peaks in the second and sixth decades of life [1]. A typical clinical presentation of psoriasis consists of sharply demarcated, silvery scaled erythematous papules and plaques with a predilection for appearing on the scalp, lumbosacral region and extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees [1, 2]. Nail involvement, which is reported in up to 50% of cases, is a potential cause of significant morbidity with regard to functional impairment, pain and cosmetic concerns [3–5]. Moreover, nail psoriasis is closely related to psoriatic arthritis; the prevalence of nail involvement has been estimated to be as high as 87% in patients with psoriatic arthritis, which represents another comorbidity associated with a considerable clinical burden on patients [3]. Dermoscopy is a highly practical diagnostic technique that allows for an in vivo evaluation of the morphological features of pigmented and non-pigmented skin lesions [6]. In recent years, dermoscopy has become increasingly appreciated as an effective tool to facilitate the clinical assessment of nail diseases [7].

Aim

The aim of the present study was to describe both classical and novel dermoscopic features of nail psoriasis and to determine the association between these features and disease severity.

Material and methods

A total of 67 consecutive patients (53 men and 14 women; mean age, 43.4 ±14.4 years (range: 18–80 years)) with psoriasis vulgaris and clinically detectable nail involvement were prospectively enrolled in the present study over a period of 6 months. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the medical ethical committee of the Ankara Numune Research and Education Hospital, Turkey. Each patient provided written informed consent prior to study inclusion. For all patients, the diagnosis of psoriasis was based upon their medical history as well as clinical and histopathological examinations. The only study inclusion criterion was the presence of any macroscopic changes in the nail unit typical of psoriasis. A detailed history regarding the onset age, psoriasis duration, accompanying arthritis, current and past medications and family history was elicited and recorded. For each patient, all fingernails and toenails were evaluated in clinical and dermoscopic examinations. All patients were graded according to the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), which was originally described by Rich et al. [8]. In addition, the physician’s global assessment (PGA) score, a global assessment of psoriasis activity, was used to classify each patient’s nail disease severity as mild, moderate, severe or very severe. A single investigator (A.Y.) performed a dermoscopic evaluation of the nail plate surfaces, periungual folds, distal free edges and hyponychium and took digital dermoscopic photographs using a MoleMax I Plus® (Derma Medical Systems GmbH, Vienna, Austria). In general, the preferred magnification power was 10-fold; however, further magnification was used when required. Firm, direct pressure was avoided to prevent blanching of the vascular structures. Ultrasound gel was used for the examination of all nail unit components other than the distal free edge, for which alcohol was used.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 16; SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). Frequencies were calculated for variables related to demographic, clinical and dermoscopic patient characteristics. Continuous variables such as age, psoriasis duration, NAPSI score and affected finger and toenail numbers are described as means ± standard deviations and ranges. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests revealed that the NAPSI scores were not normally distributed. Hence, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the NAPSI scores as well as the PGA scores (an ordinal variable) between patients with and without specific dermoscopic features. Associations between qualitative variables, such as the presence or absence of specific dermoscopic features, were tested for statistical significance using χ2 test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The duration of psoriasis ranged from 1 to 50 years (mean ± SD: 14.2 ±12.4). Arthritis was observed in 14 of 67 patients (20.9%), and a positive family history was reported by 19 of 67 patients (28.4%). All patients had at least 2 affected fingernails and the number of affected fingernails ranged from 2 to 10 (mean ± SD: 5.9 ±3.0). Toenails were affected in 12 of 67 patients (17.9%), and the number of affected toenails ranged from 1 to 10 (mean ± SD: 1.3 ±3.1). The NAPSI scores ranged from 3 to 86 (mean ± SD: 22.7 ±21.8). Additionally, 64.2% of the patients (n = 43) had mild nail psoriasis, 22.4% (n = 15) had moderate nail psoriasis, 10.4% (n = 7) had severe nail psoriasis and 3% (n = 2) had very severe nail psoriasis.

A thorough dermatological examination of the patients’ nails revealed the following: splinter haemorrhages in 73.1% (n = 49), pitting in 58.2% (n = 39), distal onycholysis in 55.2% (n = 37), salmon patches in 22.4% (n = 15), nail plate thickening and crumbling in 17.9% (n = 12), trachyonychia in 16.4% (n = 11), subungual hyperkeratosis in 9% (n = 6), transverse grooves in 9% (n = 6), leukonychia in 6% (n = 4) and lunular red spots in 1.5% (n = 1) of the patients. All clinical manifestations were also dermoscopically examined. Dermoscopic examinations revealed dilated hyponychial capillaries in 35.8% (n = 24) of the patients as well as a new dermoscopic finding, the pseudo-fiber sign, which was observed in 34.3% (n = 23) of the patients.

Patients with dilated hyponychial capillaries had significantly higher NAPSI scores than patients without dilated hyponychial capillaries (p = 0.028). Likewise, patients exhibiting the pseudo-fiber sign had significantly higher NAPSI scores than patients without this sign (p < 0.001). With regard to NAPSI scores, similar statistically significant results were observed for patients with pitting (p = 0.023), nail plate thickening and crumbling (p < 0.001), transverse grooves (p = 0.008), trachyonychia (p = 0.018), salmon patches (p = 0.022) and subungual hyperkeratosis (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of the dermoscopic features with regard to NAPSI scores

| Variable | Median (min–max) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dilated hyponychial capillaries | A (n = 43) P (n = 24) |

10.0 (3–81) 26.0 (4–86) |

0.028 |

| Pseudo-fiber sign | A (n = 44) P (n = 23) |

9.5 (3–62) 28.0 (3–86) |

< 0.001 |

| Pitting | A (n = 28) P (n = 39) |

8.5 (3–76) 18.0 (3–86) |

0.023 |

| Nail plate thickening and crumbling | A (n = 55) P (n = 12) |

10.0 (3–81) 55.5 (7–86) |

< 0.001 |

| Transverse grooves | A (n = 61) P (n = 6) |

11.0 (3–76) 54.5 (10–86) |

0.008 |

| Trachyonychia | A (n = 56) P (n = 11) |

10.0 (3–81) 32.0 (3–86) |

0.018 |

| Salmon patches | A (n = 52) P (n = 15) |

11.5 (3–81) 15.0 (8–86) |

0.022 |

| Subungual hyperkeratosis | A (n = 61) P (n = 6) |

10.0 (3–65) 75.0 (28–86) |

< 0.001 |

| Splinter haemorrhages | A (n = 18) P (n = 49) |

11.5 (3–51) 14.0 (3–86) |

0.440 |

| Onycholysis | A (n = 30) P (n = 37) |

11.5 (3–86) 14.0 (3–81) |

0.289 |

| Leukonychia | A (n = 63) P (n = 4) |

14.0 (3–86) 7.0 (5–11) |

0.112 |

| Lunular red spots | A (n = 66) P (n = 1) |

13.0 (3–86) 30.0 (30–30) |

0.437 |

Median (minimum-maximum values), A – absent, P – present.

Statistically significant relationships were observed between the severity of psoriasis, as determined using PGA, and the presence of dilated hyponychial capillaries (p < 0.001) as well as the presence of the pseudo-fiber sign (p < 0.001). In addition, significant positive associations were observed between nail plate thickening and crumbling (p < 0.001), transverse grooves (p = 0.002), trachyonychia (p = 0.012), subungual hyperkeratosis (p < 0.001) and increased nail psoriasis severity, also determined using PGA (Table 2). A significant relationship was observed between the presence of dilated hyponychial capillaries and pseudo-fiber sign (χ2 = –11.29, p < 0.001). Patients with dilated hyponychial capillaries were significantly more likely to exhibit the pseudo-fiber sign (65.2% vs. 20.5%, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of the dermoscopic features with regard to PGA scores

| Variable | Median (min–max)§ | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-fiber sign | A (n = 44) P (n = 23) |

1 (1–3) 2 (1–4) |

< 0.001 |

| Dilated hyponychial capillaries | A (n = 43) P (n = 24) |

1 (1–3) 2 (1–4) |

< 0.001 |

| Nail plate thickening and crumbling | A (n = 55) P (n = 12) |

1 (1–3) 3 (1–4) |

< 0.001 |

| Transverse grooves | A (n = 61) P (n = 6) |

1 (1–4) 3 (1–4) |

0.002 |

| Trachyonychia | A (n = 56) P (n = 11) |

1 (1–4) 2 (1–4) |

0.012 |

| Subungual hyperkeratosis | A (n = 61) P (n = 6) |

1 (1–3) 3 (2–4) |

< 0.001 |

| Splinter haemorrhages | A (n = 18) P (n = 49) |

1 (1–2) 1 (1–4) |

0.096 |

| Pitting | A (n = 28) P (n = 39) |

1 (1–4) 1 (1–4) |

0.320 |

| Distal onycholysis | A (n = 30) P (n = 37) |

1 (1–4) 1 (1–3) |

0.202 |

| Salmon patches | A (n = 52) P (n = 15) |

1 (1–3) 1 (1–4) |

0.124 |

| Leukonychia | A (n = 63) P (n = 4) |

1 (1–4) 1 (1–1) |

0.135 |

| Lunular red spots | A (n = 66) P (n = 1) |

1 (1–4) 2 (2–2) |

0.301 |

Median (minimum-maximum values), A – absent, P – present

1 – mild according to PGA score, 2 – moderate according to PGA score, 3 – severe according to PGA score, 4 – very severe according to PGA score.

Discussion

According to the results of our study, splinter haemorrhage was the most common clinical finding. Splinter haemorrhages are reddish-brown or purplish-black striae arranged in a longitudinal fashion, usually on distal parts of the nails. As the vascular structures of the nail bed run longitudinally on the epidermal–dermal ridges, a capillary rupture causes the tracking of extravasated blood down the grooves beneath the nail plate and incorporation of the blood into the ventral nail plate, thus creating ‘splinter’ shaped markings. Dermoscopy improves the visualization of splinter haemorrhages, which are more vivid when newer and darker when older [3, 4, 9–14]. Remarkably, the dermoscopic evaluation of our cases revealed not only typical longitudinal fusiform streaks (Figure 1) but also minute pinpoint or elongated serpentine-like haemorrhages (Figure 2), which in our opinion result from nail matrix involvement because the delicate grooves underneath the nail plate deteriorate as the nail plate thickens.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal fusiform splinter haemorrhages, distal onycholysis, salmon patches (20×)

Figure 2.

Serpentine-like splinter haemorrhages (green arrows), pitting and distal onycholysis (20×)

Pitting (Figure 3), distal onycholysis (Figure 1) and salmon patches (Figure 4) were the other most commonly observed manifestations in our study. Parakeratosis is among the main histopathological features responsible for these manifestations. Within the matrix, parakeratotic cells interfere with the process of normal keratinization; as the nail grows, these cells slough off, leaving coarse psoriatic pits that usually manifest as large, deep and irregularly distributed cupuliform depressions. Whereas parakeratotic lesions within the nail bed lead to salmon patches, parakeratotic cell shedding at the level of the hyponychium leads to onycholysis. These pits, which are filled with gel and surrounded by a peripheral whitish halo, are generally easily recognized via dermoscopy [3–5, 9–12]. On the other hand, some of the pits tend to have a more leukonychic appearance (Figure 5), wherein only the intermediate and ventral matrices are affected [9]. Salmon patches, also known as the oil drop sign, refer to the yellowish-red discolorations that appear as irregular translucent areas visible on the nail plate. As per our observations, psoriatic onycholysis has a distinctive dermoscopic appearance comprising a typical erythematous border encircling a white onycholytic area (Figure 1) [3–5, 10–12].

Figure 3.

Pitting (20×)

Figure 4.

Salmon patch (20×)

Figure 5.

Pitting with a leukonychic appearance (blue arrows), note the artificial staining (20×)

To the best of our knowledge, very few studies have evaluated the dermoscopic features of nail psoriasis [12, 15, 16]. Recently, Tulika et al. conducted a study similar to the one described herein. In addition, Iorizzo et al. conducted a videodermoscopic evaluation of the hyponychium in patients with psoriasis to introduce a method for visualizing the capillary network of the nails [12]. These authors aimed to assess the diagnostic value of videodermoscopy for nail psoriasis. In another descriptive dermoscopic study, Nakamura and Costa investigated the most common onychopathies, including onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, nail lichen planus and nail fragility syndrome, in 500 patients [16]. However, these findings were reported as a correspondence, without the details of the demographic and clinical data; therefore, this lack of details prevented us from comparing the results of that study with our findings.

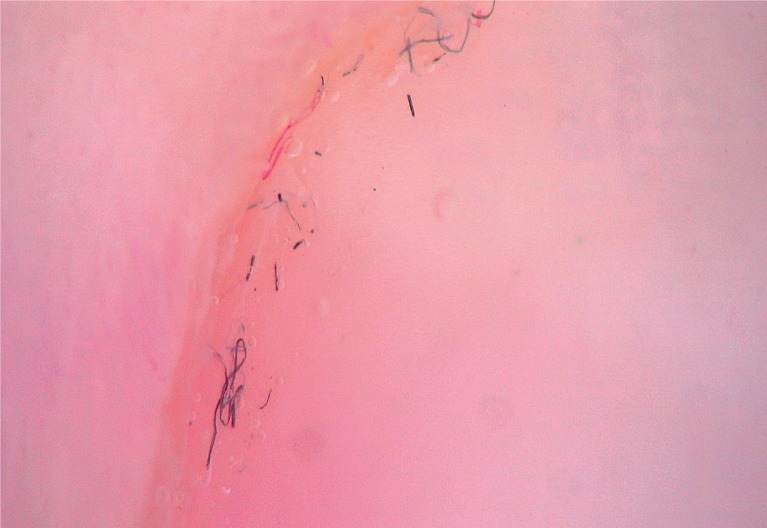

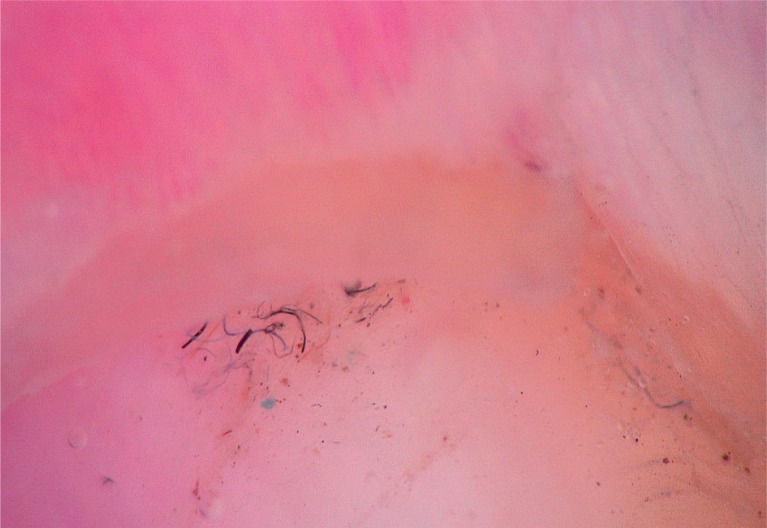

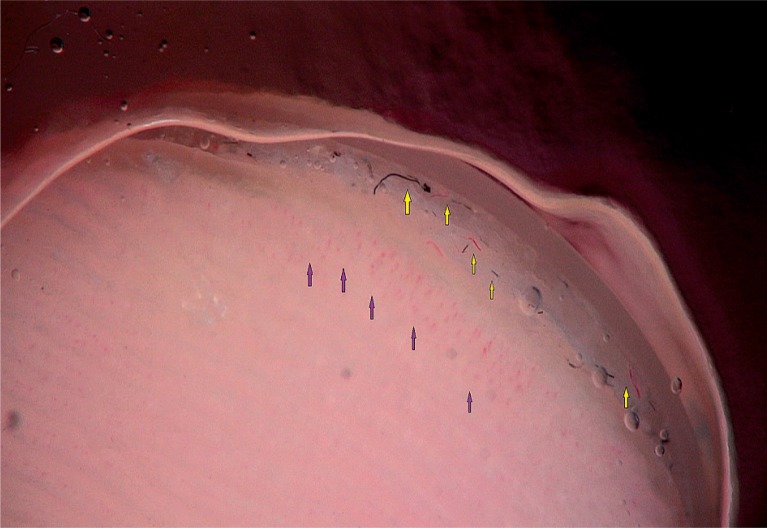

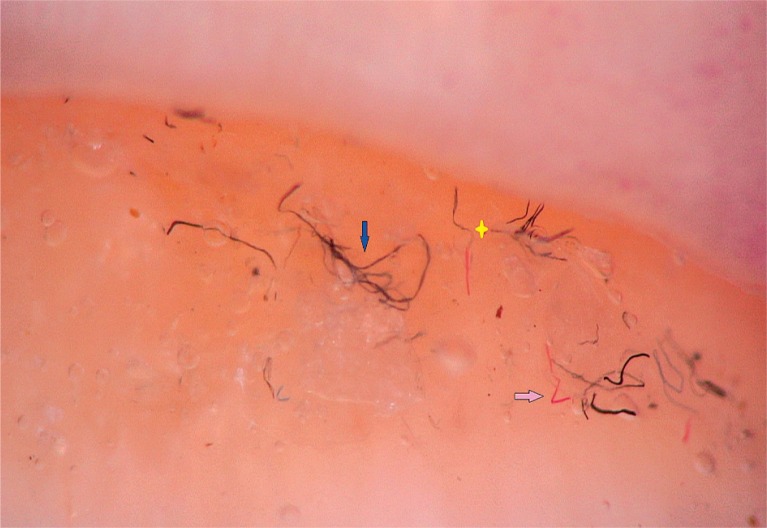

To detect signs of subclinical nail involvement in chronic plaque psoriasis, Tulika et al. investigated the dermoscopic features of nails in 68 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. These authors found dermoscopic findings in 46 patients, among whom pitting was the most common manifestation, followed by streaky nail bed capillaries and onycholysis [12]. The most important difference between that study and the present study is that we included any chronic plaque psoriasis patients with clinically evident nail involvement, as opposed to the study by Tulika et al. that enrolled only patients with subtle nail findings (i.e. not differentiated with the naked eye). On the other hand, our present study introduces the first literature report of a novel dermoscopic sign of nail psoriasis, the pseudo-fiber sign. In 34.3% of the patients, we observed red and black filamentous structures located along the cuticle (Figures 6, 7) or underneath the distal free edge on the hyponychium (Figures 8–11) or exposed areas where the nail plate had detached (Figures 12–17). We suggest that this finding is related to nail bed psoriasis and that these structures are merely bare capillaries. This sign was designated the ‘pseudo-fiber sign’ because these structures closely resemble the dermoscopically visible adherent fibers that result from lesion excoriation or ulceration [17]. These lesions are red and black in colour corresponding to the arterial and venous ends of capillaries, respectively; when taken together with the morphology, which appears nearly equal to capillaries in terms of diameter, these findings strongly indicate that the capillary network of the nail bed is the origin of these structures. Moreover, these structures are located where the nail bed meets the surface, which includes the areas of shedding and the hyponychium. In cuticular areas, these structures would correspond to ruptured nail fold capillaries, as the cuticle is a protective seal that extends from the nail folds onto the nail plate. In addition to the filamentous structures, in some patients we distinctly observed black and red pinpoint dots on bare areas where the nail plate had been shed (Figure 16) and on the hyponychium underneath the distal free edge (Figure 8). In our opinion, these dots represent the tops of the capillary loops, which are perpendicular to the surface.

Figure 6.

Pseudo-fiber sign along the cuticle (40×)

Figure 7.

Closer view of Figure 6 (100×)

Figure 8.

Pseudo-fiber sign underneath the distal free edge on the hyponychium (40×)

Figure 11.

Pseudo-fiber sign, evident distal nail bed capillaries (60×)

Figure 12.

Pseudo-fiber sign in areas of shedding (30×)

Figure 17.

Filamentous structures emerging beneath the cuticle (100×)

Figure 16.

Filamentous structures (green arrow) and pinpoint dots (purple arrows) (80×)

Figure 9.

Red and black filamentous structures under the distal free edge (yellow arrows), note the visible hyponychial capillaries (purple arrows) (40×)

Figure 10.

Red and black filamentous structures visible over the nail plate, evident distal nail bed capillaries (40×)

Figure 13.

Filamentous structures on denuded nail bed area (40×)

Figure 14.

Pseudo-fiber sign, interwoven capillaries (red arrow) (30×)

Figure 15.

Filamentous (blue arrow) and zigzag shaped (pink arrow) structures, note the two colours in one structure (yellow star) corresponding to the arterial and venous ends of a capillary remnant (100×)

Iorizzo et al. studied the capillary network of the hyponychium in patients with nail bed psoriasis and observed dilated and tortuous capillaries in all patients as well as a positive correlation between the capillary density and psoriasis severity [15]. We observed dilated, tortuous hyponychial capillaries in 35.8% of our patients. We also investigated the relationship between the dermoscopic manifestations of nail psoriasis and disease severity, which was assessed using NAPSI and PGA scores. We found that both the pseudo-fiber sign and dilated hyponychial capillaries were positively associated with severe nail psoriasis. In addition, we observed the pseudo-fiber sign more frequently in patients with dilated hyponychial capillaries. We suggest that these findings reflect the role of dermal microvascular expansion in psoriasis pathogenesis. In fact, psoriasis pathogenesis has been closely associated with increased angiogenesis. Several studies have focused on the pathogenic roles of angiogenic factors and microvascular changes in psoriasis. Increased dermal vascularity has been considered among histopathological hallmarks of psoriasis. Enhanced cutaneous blood flow, elongation and increased tortuosity and dilation of the dermal papillae capillary loops and high endothelial venule formation have been observed in psoriatic lesions [18–23].

To the best of our knowledge, the study by Iorizzo et al. was the first and only investigation of the relationship between a specific dermoscopic finding of nail psoriasis and disease severity [15]. Although the rarity of similar studies prevented us from making meaningful comparisons, it is notable that the studies by our group and Iorizzo et al. both revealed a significant relationship between dilated hyponychial capillaries and severe psoriasis. In addition, we also detected statistically significant relationships between severe nail psoriasis and other manifestations. For example, both the NAPSI and PGA scores were higher in patients with nail plate thickening and crumbling, transverse grooves, trachyonychia and subungual hyperkeratosis. On the other hand, pitting and salmon patches were only associated with higher NAPSI scores. As far as we know, our study is the first in the literature to investigate the relationships between nail psoriasis severity and other dermoscopic findings. Nevertheless, our study had several limitations, including a relatively small number of participants, lack of a control group and lack of comparative dermoscopic evaluations before and after effective psoriasis treatment. In conclusion, future studies should include larger sample sizes and control groups to better describe the novel dermoscopic manifestations of nail psoriasis and elucidate the distinct relationship between each dermoscopic finding and psoriasis severity.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl. 2):ii18–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan ES, Chong WS, Tey HL. Nail psoriasis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:375–88. doi: 10.2165/11597000-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards F, de Berker D. Nail psoriasis: clinical presentation and best practice recommendations. Drugs. 2009;69:2351–61. doi: 10.2165/11318180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schons KR, Knob CF, Murussi N, et al. Nail psoriasis: a review of the literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:312–7. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zalaudek I, Argenziano G, Di Stefani A, et al. Dermoscopy in general dermatology. Dermatology. 2006;212:7–18. doi: 10.1159/000089015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piraccini BM, Bruni F, Starace M. Dermoscopy of non-skin cancer nail disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:594–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2012.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich P, Scher RK. Nail Psoriasis Severity Index: a useful tool for evaluation of nail psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:206–12. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiaravuthisan MM, Sasseville D, Vender RB, Murphy F, Muhn CY. Psoriasis of the nail: anatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, and a review of the literature ontherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dogra A, Arora AK. Nail psoriasis: the journey so far. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:319–33. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel S, Tosti A. Nail psoriasis. 1st ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav TA, Khopkar US. Dermoscopy to detect signs of subclinical nail involvement in chronic plaque psoriasis: a study of 68 patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:272–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.156377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farias DC, Tosti A, Chiacchio ND, Hirata SH. Dermoscopy in nail psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:101–3. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piraccini BM. Nail disorders: a practical guide to diagnosis and management. 1st ed. Italia: Springer; 2014. pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iorizzo M, Dahdah M, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy of the hyponychium in nail bed psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:714–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura RC, Costa MC. Dermatoscopic findings in the most frequent onychopathies: descriptive analysis of 500 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:483–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosendahl C, Cameron A, Tschandl P, et al. Prediction without pigment: a decision algorithm for non-pigmented skin malignancy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:59–66. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0401a09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidenreich R, Röcken M, Ghoreschi K. Angiogenesis drives psoriasis pathogenesis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:232–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liew SC, Das-Gupta E, Chakravarthi S, et al. Differential expression of the angiogenesis growth factors in psoriasis vulgaris. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:201. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Kaur M, Gupta R, et al. Dermal vasculature in psoriasis and psoriasiform dermatitis: a morphometric study. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:647–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Creamer D, Allen MH, Sousa A, et al. Localization of endothelial proliferation and microvascular expansion in active plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:859–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodfield M, Hull SM, Holland D, et al. Investigations of the ‘active’ edge of plaque psoriasis: vascular proliferation precedes changes in epidermal keratin. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:808–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowe PM, Lee ML, Jackson CJ, et al. The endothelium in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:497–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb08702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]