Resting-state functional MRI is used as a complementary method to invasive techniques to inform current debates on the organization of the macaque lateral frontal cortex. Given that the macaque cortex serves as a model for the human cortex, our results help generate more fine-tuned hypothesis for the organization of the human lateral frontal cortex.

Keywords: cortical areas, in vivo parcellation, functional connectivity, premotor, prefrontal

Abstract

Investigations of the cellular and connectional organization of the lateral frontal cortex (LFC) of the macaque monkey provide indispensable knowledge for generating hypotheses about the human LFC. However, despite numerous investigations, there are still debates on the organization of this brain region. In vivo neuroimaging techniques such as resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can be used to define the functional circuitry of brain areas, producing results largely consistent with gold-standard invasive tract-tracing techniques and offering the opportunity for cross-species comparisons within the same modality. Our results using resting-state fMRI from macaque monkeys to uncover the intrinsic functional architecture of the LFC corroborate previous findings and inform current debates. Specifically, within the dorsal LFC, we show that 1) the region along the midline and anterior to the superior arcuate sulcus is divided in two areas separated by the posterior supraprincipal dimple, 2) the cytoarchitectonically defined area 6DC/F2 contains two connectional divisions, and 3) a distinct area occupies the cortex around the spur of the arcuate sulcus, updating what was previously proposed to be the border between dorsal and ventral motor/premotor areas. Within the ventral LFC, the derived parcellation clearly suggests the presence of distinct areas: 1) an area with a somatomotor/orofacial connectional signature (putative area 44), 2) an area with an oculomotor connectional signature (putative frontal eye fields), and 3) premotor areas possibly hosting laryngeal and arm representations. Our results illustrate in detail the intrinsic functional architecture of the macaque LFC, thus providing valuable evidence for debates on its organization.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Resting-state functional MRI is used as a complementary method to invasive techniques to inform current debates on the organization of the macaque lateral frontal cortex. Given that the macaque cortex serves as a model for the human cortex, our results help generate more fine-tuned hypothesis for the organization of the human lateral frontal cortex.

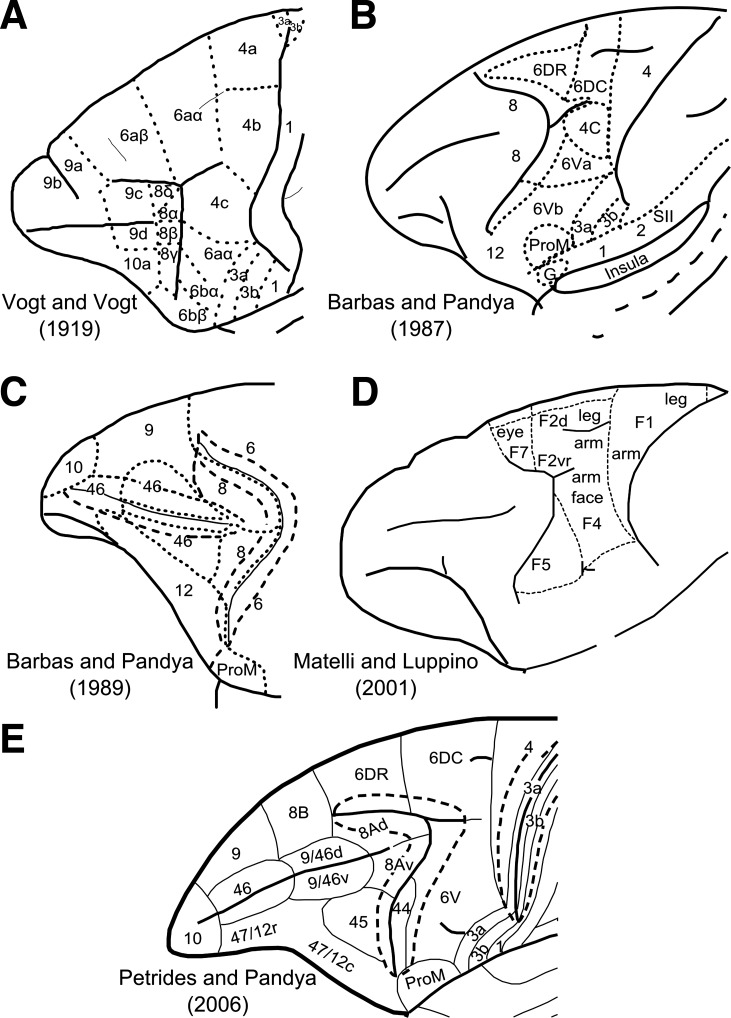

cytoarchitectonic and myeloarchitectonic investigations of the macaque monkey lateral frontal cortex (LFC) have provided critical information on its organization (e.g., Barbas and Pandya 1987, 1989; Petrides and Pandya 1994; Vogt and Vogt 1919; Walker 1940). Furthermore, investigations of the cortico-cortical connections of these areas with invasive tract-tracing methods have provided evidence of distinct connectivity profiles that characterize these cytoarchitectonically distinct areas (e.g., Cavada and Goldman-Rakic 1989; Petrides and Pandya 2006; Yeterian et al. 2012). Thus cytoarchitectonic and connectional investigations have unveiled a mosaic of cortical areas within the LFC (Fig. 1) that participate in specific large-scale networks. In addition, electrophysiological recordings in these areas and selective lesion studies have provided evidence of relative functional specializations of the neuronal populations in these cortical areas (e.g., Kaping et al. 2011; Petrides 2005). Despite considerable progress in understanding the cellular and connectional organization of the LFC, there are discrepancies in the reported maps. Some of the discrepancies stem from differences in the criteria employed to outline areas and/or the nonoptimal sectioning of the gyrated primate cortex. Thus differences between various maps (Barbas and Pandya 1987, 1989; Matteli and Luppino 2001; Petrides and Pandya 1994; Petrides et al. 2005; Vogt and Vogt 1919; Walker 1940) give rise to controversies that need to be resolved. Such an endeavor is crucial because findings in the macaque LFC are indispensable because of the level of detail that they offer in generating hypotheses about the organization of the human LFC (e.g., Amiez and Petrides 2009; Margulies and Petrides 2013; Passingham and Wise 2012). Specifically, with respect to the dorsal LFC, inconsistencies pertain to the presence of distinct cortical areas along the superior frontal region anterior to the end of the superior arcuate sulcus (Fig. 1, A, C, and E), the caudal premotor cortex (Fig. 1, A, B, D, and E), and the border of the dorsal and ventral motor/premotor areas (Fig. 1, A, B, and D). With respect to the ventral precentral region that extends from the central sulcus to the inferior ramus of the arcuate sulcus, several areas have been identified (e.g., Barbas and Pandya 1987; Belmalih et al. 2009; Gerbella et al. 2007; Matelli et al. 1985; Petrides and Pandya 1994; Petrides et al. 2005). There is, however, still debate concerning the extent and even the presence of certain cortical areas in this region in macaque monkeys. Such a debate and controversy obscures aspects concerning the evolution of areas and circuitry related to aspects of language. Specifically, the presence of a macaque homologue of part of the so-called Broca's region (area 44) in humans has been debated (Matelli et al. 2004). The presence of a cytoarchitectonic homologue of area 44 in the macaque inferior arcuate sulcus and its involvement with orofacial function has been established and clearly distinguished from ventral premotor areas (Petrides and Pandya 1994; Petrides et al. 2005). This observation was recently confirmed in further cytoarchitectonic analysis of the ventrolateral frontal region in the macaque (Belmalih et al. 2009). Moreover, it has been shown that area 44, involved with orofacial/somatomotor functions, lies at the fundus of the most ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus, whereas the cortex lying more dorsally is implicated in visuomotor attentional functions (area 8Av) (Petrides et al. 2005). It is therefore desirable to obtain further evidence to corroborate and further elucidate the existence and borders of the distinct areas in the ventral precentral region.

Fig. 1.

A–E: cytoarchitectonic maps of the lateral surface of the frontal cortex. Certain maps parcellate only parts of the lateral frontal surface. A: modified from Vogt and Vogt (1919). B: modified with permission from Barbas and Pandya (1987). C: modified with permission from Barbas and Pandya (1989). D: adapted from NeuroImage, Vol. 14, Matelli M and Luppino G, Parietal circuits for action and space perception in the macaque monkey, Pages S27–S32, copyright 2001, with permission from Elsevier. E: modified with permission from Petrides and Pandya (2006).

In vivo neuroimaging techniques, such as resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI), can unveil distinct connectional divisions of the primate brain that are consistent, though not corresponding in a one-to-one fashion, with gold-standard tract-tracing findings (Margulies et al. 2009; Miranda-Dominguez et al. 2014). Because of their noninvasive nature, such techniques are used for delineating areas in the human brain and demonstrate good colocalization with cytoarchitectonically defined areas (e.g., Goulas et al. 2012; Kelly et al. 2010; Margulies and Petrides 2013).

In this study, we perform a data-driven connectivity-based parcellation of the LFC in the macaque monkey based on rsfMRI to inform debate on existing organization schemes derived from invasive methods. Specifically, we aim to find evidence for connectional divisions and relate them to proposed parcellation schemes derived from histological analysis for which consensus is still lacking. RsfMRI, despite its disadvantage with respect to resolution and specificity, allows the connectivity-based parcellation of the whole extent of the LFC in a quantitative manner, whereas invasive tract-tracing techniques are restricted to a limited number of areas that can be injected. Clearly, rsfMRI is not a substitute of histological analysis but rather a complementary modality that can inform previous histologically derived parcellation schemes. Lastly, a data-driven rsfMRI connectivity-based parcellation of the macaque LFC establishes the foundation for future macaque-human comparisons with the same modality (e.g., Hutchison et al. 2012; Mantini et al. 2013; Margulies et al. 2009; Sallet et al. 2013) by overcoming the limitation of manual seed placement and adoption of specific a priori defined maps (Margulies et al. 2009; Sallet et al. 2013).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

High-resolution rsfMRI data were acquired from 6 macaque monkeys at 7 T. All experimental methods were carried out in accordance with the Canadian Council of Animal Care policy on the use of laboratory animals and a protocol approved by the Animal Use Subcommittee of the University of Western Ontario Council on Animal Care. On the day of scanning, the monkeys were anesthetized by intramuscular injections of atropine (0.4 mg/kg), ipratropium (0.025 mg/kg), and ketamine hydrochloride (7.5 mg/kg). Afterwards, 3 ml of propofol (10 mg/ml) were administered intravenously and oral intubation was carried out. Maintenance of anaesthesia was conducted by using 1.5% isoflurane mixed with oxygen. Animals had spontaneous respiration throughout the duration of the experiment. The animals were placed in a custom-built chair and head-fixed while they were in the magnet bore. Isoflurane level was reduced to 1% during functional image acquisition. The animals' vital signs were monitored throughout the duration of the image acquisition [rectal temperature via a fiber-optic temperature probe (FISO, Quebec City, QC, Canada), respiration via bellows (Siemens, Union, NJ), and end-tidal CO2 via capnometer (Covidien-Nellcor, Boulder, CO)]. Physiological parameters were in the normal range throughout the image acquisition procedure (temperature: 36.8°C; respiration: 24–32 breaths/min; end-tidal CO2: 31–40 mmHg). A heating disk (SnuggleSafe; Littlehampton, West Sussex, UK) and thermal insulation were used to maintain body temperature. The data were acquired on an actively shielded 7-T 68-cm horizontal bore scanner with a DirectDrive console (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and a Siemens AC84 gradient subsystem (Erlangen, Germany) operating at a slew rate of 350 mT·m−1·s−1. An in-house-designed and manufactured conformal five-channel transceive primate head radiofrequency coil was used for acquiring magnetic resonance images. The coil consisted of an array of elements wrapped 270° circumferentially around the head. For each monkey, 10 runs of 150 echo planar imaging functional volumes (TR = 2,000 ms; TE = 16 ms; flip angle = 70°, matrix = 96 × 96; field of view = 96 × 96 mm; voxel size = 1 mm isotropic) were acquired, each run lasting 5 min. One T1-weighted anatomical image (TE = 2.5 ms; TR = 2,300 ms; TI = 800 ms; field of view = 96 × 96mm; 750-μm isotropic resolution) was also acquired (see Babapoor-Farrokhran et al. 2013 for details). Data were preprocessed with the REST toolbox (http://restfmri.net/forum/REST_V1.8) and SPM5 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging) and included realignment, slice-time correction, coregistration of functional and anatomical scans, regressing out of white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signal, linear trends, and six movement parameters. For the segmentation of the structural volumes, the macaque tissue priors provided in McLaren et al. (2009) were used. White matter and cerebrospinal fluid signal was extracted by using the corresponding probability tissue type images from each animal. A 0.8 threshold was applied to these images, and subsequently, the mean signal of the remaining voxels resulted in the white matter and cerebrospinal fluid regressors. In addition, bandpass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz) and spatial smoothing (2-mm FWHM) was applied. Such preprocessing steps are similar with those applied in previous rsfMRI macaque data (e.g., Hutchison et al. 2011; Mantini et al. 2013; Sallet et al. 2013).

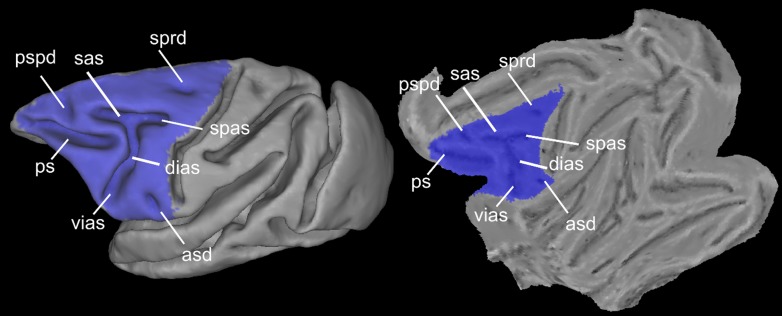

The LFC was delineated on the F99 template (Van Essen 2004) available in CARET (http://brainvis.wustl.edu/wiki/index.php/Caret:About) to create an LFC mask (Fig. 2). We did not extend the posterior part of the mask until the fundus of the central sulcus, encompassing the presumed posterior limit of the primary motor cortex, to avoid examination of this region prone to partial volume effects and contamination of the fMRI signal between the posterior (somatosensory areas areas) and anterior (primary motor area) banks of the central sulcus. The analysis was restricted to the left hemisphere for setting the foundation for subsequent comparative analysis with presumed left-lateralized, language-related areas/networks involving the human LFC. Moreover, we restricted the analysis to the left LFC for comparisons with histologically derived maps, which mostly depict the left LFC. The LFC mask was transformed to the native space of each animal, and the rsfMRI time courses of each gray matter voxel within the LFC patch were extracted. For each run, a within-patch voxel-to-voxel correlation matrix was computed, and these matrices were then averaged. The N × N average matrix from each animal, where N is the number of gray matter voxels within the LFC mask, was thresholded to result in a density of 0.01, thus creating a fully connected, undirected, and weighted graph. Density is the ratio of connections/edges in the graph to the maximum possible edges in the graph given its number of nodes N (in our case, number of voxels). A high sparsity, i.e., low density, for the graphs, which at the same time ensures full connectedness, was chosen to decrease computational time and detect modules/areas that otherwise might not be detectable due to the “resolution limit” (Fortunato and Barthélemy 2007) of the employed module detection algorithm. The Louvain module detection algorithm (Blondel et al. 2008) was applied as in Goulas et al. (2012), incorporating the consensus strategy described in Lancichinetti and Fortunato (2012).

Fig. 2.

Spatial extension of the lateral frontal cortex (LFC) mask used and major macroscopic landmarks within the LFC depicted on the F99 fiducial and flat surface. asd, anterior subcentral dimple; dias, dorsal compartment of the inferior branch of the arcuate sulcus; ps, principal sulcus; pspd, posterior supraprincipal dimple; sas, superior branch of the arcuate sulcus; spas, spur of the arcuate sulcus; sprd, superior precentral dimple; vias, ventral part of the inferior branch of the arcuate sulcus.

Briefly, the algorithm applies a greedy strategy for assigning each voxel to a module to maximize the modularity value Q (Blondel et al. 2008):

| (1) |

with ei representing the number of edges within module i, di representing the total degree (i.e., number of functional connections/edges) of the nodes belonging to module i, and m representing the total number of edges in the graph. This value expresses how “surprising” the connectivity between voxels belonging to the same module is in relation to the connectivity expected by chance (see Blondel et al. 2008 for details). Note that the number of modules are not determined a priori but are derived from the algorithm and the data set at hand. In other words, the number of modules is such so that the Q value is maximized. Moreover, the algorithm will always result in a solution and a corresponding Q value. Hence, the Q values are compared with what would be expected by chance by adopting two null models (see below). The aforementioned approach is stochastic; i.e., applying the algorithm many times does not guarantee the exact same solution/module decomposition. Moreover, these solutions might be substantially different and exhibit a high modularity value Q, a phenomenon termed “degeneracy of modularity” (Good et al. 2010). Because of the presence of equally good solutions, instead of picking up the solution with the highest value Q, the solutions can be combined with a consensus strategy (Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2012). A N × N consensus matrix is formed from the solutions of the module detection algorithm, but now an entry i, j in the matrix does not denote the correlation of the rsfMRI time courses of voxel i and j, but rather the frequency with which these voxels have been assigned to the same module. We adopted this consensus strategy because it has been shown to lead to improved accuracy and stability of parcellation results (Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2012). The above strategy has two free parameters, i.e., the number of solutions to form the consensus matrix and the threshold to be applied. We chose 100 as the number of solutions as input to the consensus clustering, since extensive previous analysis showed that above ∼50 solutions there is a plateau in accuracies (see Supplementary Material in Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2012). Moreover, the threshold parameter does not seem to influence the accuracy, and consequently, we chose a value of 0.5 to speed up the procedure (see Supplementary Material in Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2012). The consensus matrix is then fed to the module detection algorithm after the application of the threshold (0.5), i.e., two voxels are assigned to the same module in half or more of the solutions, to produce 100 solutions. Subsequently, the consensus matrix is formed anew, and the procedure is iteratively applied until the consensus matrix becomes a block diagonal matrix with ones (zeros) denoting voxels always assigned to the same (different) module.

The “resolution limit” of the module detection algorithm (Fortunato and Barthélemy 2007) can lead to the merging of distinct modules (in our case, distinct LFC areas). The resolution limit is grounded in the fact that the modularity maximization relies on a global null model for determining how many connections are expected by chance and thus depends on the total number of connections in the network. In other words, given the number of connections in the network to be split in modules, well-defined modules might be merged in one (Fortunato and Barthélemy 2007), thus defining a lower bound as a possible criterion for iteratively subsplitting modules. Several approaches have been suggested for overcoming the resolution limit (e.g., Ruan and Zuang 2008) but with considerable drawbacks (e.g., evidence of overpartitioning leading to falsely identified modules) and other limitations (for a discussion see Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2011). We currently follow a pragmatic approach dictated by our current aims. Thus, informed by previous cytoarchitectonic parcellation schemes, potentially merged modules will be taken into account separately and fed into a second parcellation. This approach is suggested for investigating further subdivisions that may be concealed in the results of the first parcellation (Fortunato and Barthélemy 2007) and has been previously applied in neuroimaging analysis (Nelson et al. 2010).

To assess the statistical significance of the parcellation resulting from the module decomposition, two null models were adopted, i.e., the degree-preserving rewiring null model (Rao and Bandyopadhyay 1996; Maslov and Sneppen 2002), with degree in our case denoting the number of functional connections of a voxel, and the null correlation matrix model (Zalesky et al. 2012). Whereas the former model preserves certain topological properties of the original network, i.e., the degree distribution, the latter aims at creating null correlation matrices that preserve the distribution of the correlation values of the original network and the increased clustering of the network introduced by the correlation metric itself (Zalesky et al. 2012). Briefly, the degree-preserving rewiring null model is derived as follows: Two pairs of interconnected nodes (a–b, c–d) are randomly selected and rewired be swapping partners, i.e., a–d, b–c. The process is repeated many times, in this case 100 times, so that any topological pattern of the original network, apart from the degree distribution, number of nodes and edges, is destroyed. The null correlation matrices were generated with the Hirschberger-Qi-Steuer algorithm that creates correlation matrices with matched mean and variance to the original matrices (see for details see Appendix in Zalesky et al. 2012).

For assessing the stability of the parcellation results, the aforementioned analysis was conducted in the odd and even runs separately. Hence, for each animal, two partitions derived from the odd and even runs were obtained. The more similar these partitions are to the partition obtained with all the runs and in between them, the more stable the solutions can be considered. The similarity of the partitions was quantified with the normalized variation of information (Meila 2007). This metric has theoretical values in the range [0,1], with 0 indicating identical partitions and 1 completely different ones.

The above approach resulted in a module map for each animal that can be considered to correspond to distinct areas. The module maps from each animal were grouped together in a data-driven manner after normalization to F99 space by using the center of mass as a similarity criterion (Goulas et al. 2012). This resulted in a probability map for each module denoting in each voxel the frequency of colocalization of each module across the animals. For estimating the functional connectivity (FC) map of each module at the group level, a spherical seed (1.5-mm radius) was placed at the weighted center of mass of each probability map. To ensure the placement of the seed in the most “representative” coordinate, before the calculation of the weighted center of mass, the probability maps were thresholded to contain voxels denoting colocalization in at least two animals. Time series from the seeds were extracted and entered as regressors in a multiple regression model combining all runs from all animals in a fixed-effects analysis. This procedure resulted in FC maps for each module at the group level. The maps were thresholded at a cluster level q < 0.05 (family-wise error; cluster-defining threshold: P < 0.001, uncorrected). To quantify the similarity of the FC maps, all pairwise spatial similarities were computed by calculating 1 − r between the coefficients (“con*.nii” maps in SPM) for each module derived from the aforementioned fixed-effects analysis, where r is Pearson's correlation coefficient. For computing pairwise similarities, we restricted the analysis in gray matter voxels after segmenting the F99 template. The pairwise similarities were used to construct a dendrogram with the average linkage method. The faithfulness of preservance of the original distances in the dendrogram was assessed with the cophenetic coefficient. The analysis was performed with custom MATLAB (The MathWorks) functions and functions from the Brain Connectivity Toolbox (Rubinov and Sporns 2010).

RESULTS

The module detection algorithm resulted in high modularity values (Q: mean 0.83, SD 0.01, P < 0.01) compared with those obtained from both null models (Qrewired: mean 0.26, SD 0.04; Qnull correlation: mean 0.27, SD 0.04). Good correspondence between the partitions estimated separately from the odd and even runs was observed, resulting in very low variation of information and thus highly similar partitions (mean 0.13, SD 0.02). The observed similarity of the partitions from the odd and even runs was much higher compared with the randomized affiliation vectors derived from the module detection algorithm (mean 0.65, SD 0.03). In addition, the variation of information in the partitions obtained from the odd and even runs was very similar to the partition obtained from all runs (variation of information: mean 0.09, SD 0.02). These results highlight that our parcellation is characterized by stability, in the sense that the similarity of partitions obtained from odd and even runs gave rise to values very near the theoretical maximum similarity and substantially differed from values expected by chance. Moreover, the parcellation is statistically significant, since the Q values differed from the ones obtained from the two null models.

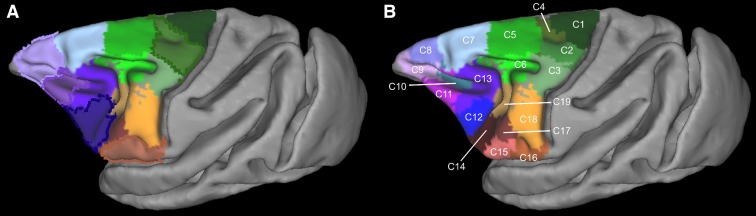

The modules obtained in each animal resulted in 14 clusters of modules, hereafter referred to as “clusters,” at the group level (Fig. 3A). All these clusters were formed from modules that were present in at least 5/6 animals. The spatial layout of the clusters indicates a neuroanatomically realistic parcellation (see below and Fig. 1). Certain clusters seem to encompass more than two distinct cortical areas (Fig. 3A, outlined borders). Specifically, the green outlined cluster (Fig. 3A) seems to encompass areas 6aα and 4b of Vogt and Vogt (1919) (Fig. 1A). The brown outlined cluster (Fig. 3A) seems to encompass areas ProM, 3a, 3b, and 1 (Fig. 1E). The blue outlined cluster (Fig. 3A) seems to encompass areas 45 and 44 (Fig. 1E). The purple outlined cluster (Fig. 3A) seems to encompass areas 47 and parts of 9/46v (Fig. 1E). Finally, the light purple outlined cluster (Fig. 3A) seems to encompass areas 46, 9, and 10 (Fig. 1E). To find out if these clusters could be further subdivided, they were submitted to a separate second-pass parcellation. This resulted in parcellations with Q values higher than chance (mean 0.80, SD 0.01, P < 0.01; Qrewired: mean 0.29, SD 0.05, Qnull correlation: mean 0.48, SD 0.08, P < 0.01). Again, the modules were grouped across the animals, resulting in 10 clusters. These clusters, along with the ones from the first-pass analysis, resulted in 19 clusters (C1–C19; Fig. 3B). This parcellation is the focus of our subsequent analysis. Specifically, only the clusters located at the dorsal LFC, i.e., C1–C8, and ventral LFC, i.e., C14–C19 (Fig. 3B), are the focus of the present report. The results from the clustering in the principal sulcus were not interpretable in terms of prior parcellation schemes and therefore not satisfactory. This is presumably due to the partial volume effects and signal contamination of the fundus and the dorsal and ventral banks of the principal sulcus, rendering the uncovering of the connectional heterogeneity of this LFC region problematic. Higher resolution data seem to be necessary for examining this region with rsfMRI (see also Limitations and Perspectives).

Fig. 3.

Summary of the parcellation results of the first (A) and second (B) “pass” of the algorithm. The depicted results constitute winner-takes-all maps. The modules constituting each cluster are forming a probabilistic map (see Fig. 4). These probabilistic maps are combined to produce the depicted winner-takes-all maps by assigning each voxel a unique integer corresponding to the cluster exhibiting the highest probability in this voxel. Subsequently, each cluster is coded with a unique color and named arbitrarily C1, C2, …, C19. This cluster-wise color scheme is also followed in Figs. 4 and 5. Spatial location of the clusters dictates their color “family”: dorsal motor/premotor clusters are color coded with shades of green, ventral premotor clusters with brown/orange, and prearcuate clusters with blue/violet. Borders around clusters in A indicate those that were further subdivided on the basis of the second-pass results depicted in B (see results).

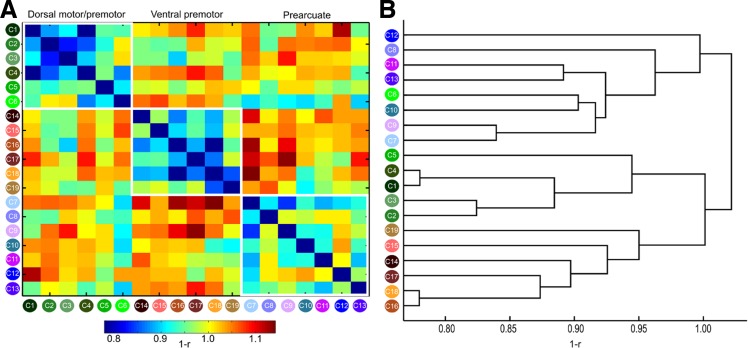

The FC maps of each cluster that were fed into a hierarchical clustering resulted in the grouping of the clusters into three broad connectivity families: dorsal motor/premotor, ventral premotor, and prearcuate/prefrontal (Fig. 4). The dendrogram was constructed with the average linkage method because this method resulted in the most faithful representation of the original distances, as assessed with the cophenetic coefficient (0.74), compared with single (0.51), complete (0.67), and weighted (0.72) linkage methods. A notable exception in the connectional segregation, which largely coincides with the spatial segregation of the clusters, was postarcuate C6, which was not grouped with the dorsal motor/premotor clusters but with the prearcuate ones (Figs. 3B and 4).

Fig. 4.

A: connectivity similarity matrix for all the clusters. Note that the clusters are arranged on the basis of their spatial location to 3 broad groups, dorsal motor/premotor, ventral motor/premotor, and prearcuate, indicated by the white outlines. Connectivity similarity was measured as 1 − r, where r is Pearson's correlation coefficient; hence lower (higher) values indicate higher (lower) connectivity similarity (see materials and methods). B: dendrogram constructed on the basis of connectivity similarity of the clusters (see materials and methods and results). Three broad groups are discernible, broadly coinciding with the groups defined by spatial location (Fig. 3B). Thus groups discernible on the basis of spatial or connectional information largely coincide (compare the groupings of the clusters in A and B). A notable exception is C6, which seems more affiliated, on a connectional basis, with the prearcuate group, despite its postarcuate location (see results and discussion).

Below we document the results and interpret the dorsal and ventral LFC clusters on the basis of histologically defined cortical areas as well as topographic and FC information. A qualitative comparison is necessitated by the lack of quantitative probabilistic maps in a stereotaxic space for the macaque monkey LFC. We first describe the dorsal LFC results proceeding along the dorsal part of the frontal lobe, following a caudal-to-rostral direction from the central sulcus to the frontal pole, followed by the results on the ventral LFC.

Dorsal LFC

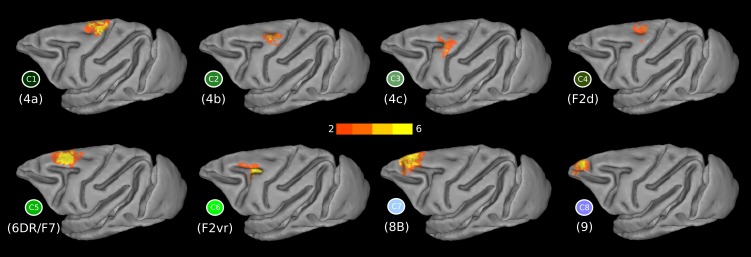

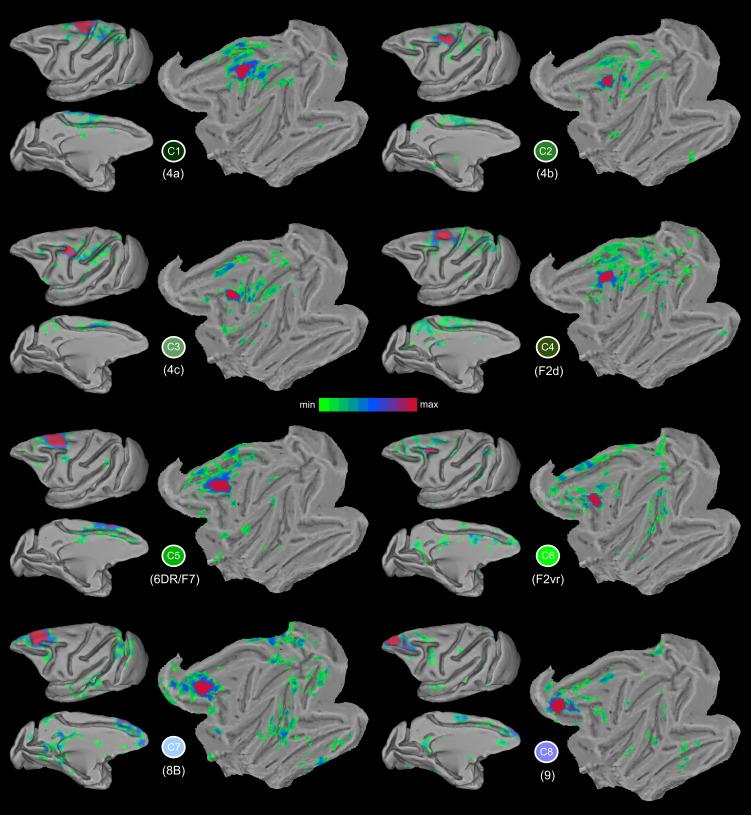

Cluster C1.

In the most dorsocaudal part of the frontal lobe, immediately in front of the central sulcus, there is cluster C1, which most probably corresponds, from a topographic perspective, to a subdivision of the primary motor cortex, defined as area 4a by Vogt and Vogt (1919) (Fig. 1A). Its weighted center of mass (WCOM) in F99 space is (x = −7.4, y = −10.0, z = 24.3) (all subsequent coordinates are in F99 space; Fig. 5). On the basis of electrical stimulation data, this region of the motor cortex corresponds to the trunk and lower limbs of the body (Vogt and Vogt 1919; Woolsey 1952). C1 is characterized by connectivity with the medial wall of the primary motor cortex, the adjacent supplementary motor cortex, and the caudal cingulate motor areas (Picard and Strick 2001). There is also strong connectivity with the superior parietal lobule (areas PE and PEc) and the anterior part of the intraparietal sulcus (Petrides and Pandya 1984; case 1 in Bakola et al. 2013). This region has connectivity with the adjacent part of the primary motor cortex (area 4b) and the rostrally adjacent dorsal premotor cortex (F2/6DC). These connectional characteristics are reflected in the FC map of C1 (Fig. 6). Connectivity was restricted to the dorsal motor and premotor areas (Fig. 6), consistent with the presumed evolutionary origins of these areas from the archicortical trend (Barbas and Pandya 1987). This affiliation with the dorsal constellation of LFC areas was also evident when quantifying the similarity of the whole brain connectivity with the rest of the clusters, since C1 belongs to the dorsal motor/premotor group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Probabilistic maps of the dorsal LFC clusters and their respective functional connectivity (FC) maps. Colors from orange to yellow in the probabilistic maps denote low to high overlap across animals. The faded colored borders correspond to the dorsal clusters as depicted in the winner-takes-all map in Fig. 3B.

Fig. 6.

Functional connectivity maps of the dorsal clusters in the F99 template. Higher t values are denoted with red/purple colors. Each cluster is denoted by its unique color (see Fig. 3B).

Cluster C2.

C2 (WCOM x = −13.4, y = −6.1, z = 21.7) is located dorsocaudally to the most posterior part of the spur of the arcuate sulcus and ventral to C1 (Fig. 5). Its location corresponds well with the 4b subdivision of primary motor area 4 by Vogt and Vogt (1919) (Fig. 1A). Its connectivity pattern in the medial wall involves supplementary motor area (SMA; cases 3 and 7 in Morecraft and Van Hoesen 1993) and area PGm (case 9 in Petrides and Pandya 1984). On the lateral surface, it involves areas PE (case 1 in Bakola et al. 2013) and its extension to the intraparietal sulcus, i.e., area PEa (case 1 in Petrides and Pandya 1984). These connectional characteristics are reflected in the FC map of C2 (Fig. 6). From a functional standpoint, microstimulation in this area elicits shoulder, wrist, and elbow movements (Tokuno and Nambu 2000). In addition, this part of the primary motor cortex is implicated in hand kinematics (Archambault et al. 2011).

Cluster C3.

C3 (WCOM x = −16.6, y = −1.9, z = 18.6) is located posterior to the spur of the arcuate sulcus, with a focus on the posterior-most part of the spur (Fig. 5), possibly involving the part of the primary motor cortex that Vogt and Vogt (1919) referred to as 4c (Fig. 1A). This region is the focus of connectivity from the anterior part of the superior parietal lobule and the anterior part of the adjacent medial bank of the intraparietal cortex (case 1 in Petrides and Pandya 1984). The connectivity of C3 is prominent with the pre-SMA on the medial wall, as well as parietal area PGm. Extensive connectivity was also observed with the rostral part of the intraparietal sulcus and the rostral superior parietal lobule (area PE) (case 2 in Bakola et al. 2013). These connectional characteristics are reflected in the FC map of C3 (Fig. 6). The connectivity of C3 is clearly affiliated with the dorsal motor/premotor group (Fig. 4). From a functional standpoint, microstimulation in this area elicits shoulder, wrist, and elbow movements (Tokuno and Nambu 2000).

Cluster C4.

C4 (WCOM x = −8.2, y = −4.9, z = 23.4), which lies anteroventral to C1, is focused around the superior precentral dimple (Fig. 5), where area 6DC (also known as F2) is located. More specifically, C4 is colocalizing with dorsal subdivision F2 (Luppino et al. 2003) (Fig. 1D). The connectivity of C4, consistent with tract-tracing studies, is with supplementary motor cortex and to a lesser extent with the cingulate motor areas (Luppino et al. 2003). In addition, it exhibits strong connectivity with the superior parietal lobule (areas PE and PEc), the adjacent intraparietal sulcus (Marconi et al. 2001; Petrides and Pandya 1984), the inferior parietal lobule (case 1 in Petrides and Pandya 1999), and the medial parietal region, especially area 31, and the more dorsal anterior area PEci (case 13 in Morecraft et al. 2012). These connectional characteristics are reflected in the FC map of C4 (Fig. 6). C4 connectivity assigns this cluster to the dorsal motor/premotor group (Fig. 4). Microstimulation in this area elicits trunk-related and proximal forearm movements (Raos et al. 2003).

Cluster C5.

Another distinct cluster, C5 (WCOM x = −8.4, y = 4.1, z = 21.8), is located above the superior branch of the arcuate sulcus, which corresponds to the location of area 6DR (also known as F7) (Fig. 1, D and E, and Fig. 3). The peak of the probabilistic map lies in the anterior part of this cluster (Fig. 5). Similarly to C4, C5 shows strong connectivity with the adjacent dorsal premotor cortex and the adjacent medial wall of the frontal lobe, where the pre-SMA region lies. The connectivity also extends into the cingulate sulcus involving the cingulate motor areas (Fig. 6). This pattern is consistent with tract-tracing results (case 13 FB in Luppino et al. 2003). C5 is distinguishable from C4 in its more anterior connectivity along the medial wall to the pre-SMA, as opposed to C4 connectivity with the more posteriorly located SMA (Luppino et al. 2003) (Fig. 6). C5 connectivity assigns this cluster to the dorsal motor/premotor group (Fig. 4). From a functional standpoint, this area is implicated in oculomotor activity (Schlag and Schlag-Rey 1987), but presumably with a different behavioral context than oculomotor activity of the frontal eye field (FEF) (Fujii et al. 2000).

Cluster C6.

C6 (WCOM x = −12.6, y = 2.8, z = 16.4) is focused around the spur of the arcuate sulcus with the peak of the probability map in the posterior part of the spur (Fig. 5). The topography resembles the subdivision of F2 described as F2vr by Luppino et al. (2003) (Fig. 1D; see also discussion). Consistent with tract-tracing studies involving area F2vr, the C6 connectivity pattern involves the cingulate motor areas, i.e., CMAd, CMAv, CMAr, and parts of dorsal prefrontal cortex (Luppino et al. 2003). In addition, there was connectivity with the dorsal prelunate region, the parieto-occipital sulcus (case 2 in Yeterian and Pandya 2010; Stepniewska et al. 2005), the vicinity around the accessory parieto-occipital sulcus possibly hosting areas V6/V6A (Luppino et al. 2005), the medial intraparietal area (Marconi et al. 2001), and the caudal superior parietal lobule (case 6 in Petrides and Pandya 1984). All the above connectional characteristics are reflected in the FC map of C6 (Fig. 6). Interestingly, despite the fact that C6 lies partly within the caudal bank of the arcuate sulcus (Fig. 5), its connectivity pattern is clearly more similar to prearcuate clusters compared with the dorsal motor/premotor ones (Fig. 4). Neurons in the vicinity of this cluster seem relevant for integrating target and body parts information for action planning (Hoshi and Tanji 2000) and involve complex proximal and distal forearm movements (Raos et al. 2003). Moreover, vision-related responses have been observed in this cortical area (Fogassi et al. 1999).

Clusters C7 and C8.

Along the superior frontal region, anterior to C5, two distinct clusters, C7 (WCOM x = −7.8, y = 14.3, z = 18.7) and C8 (WCOM x = −6.5, y = 22.4, z = 14.8), were uncovered (Fig. 5). In the past, this region had been treated as either two distinct areas, namely, areas 8B and 9, by Walker (1940) and Petrides and Pandya (1994), or as one, i.e., area 9 (Barbas and Pandya 1989) (Fig. 1, C and E). Our results demonstrate that, on a connectional basis, two distinct clusters can be distinguished.

C7 extends from the anterior end of the superior branch of the arcuate sulcus and continues as far as the posterior supraprincipal dimple, which is the region were area 8B lies (Fig. 1E). This area marks the transition from premotor areas to the prefrontal region, as evident in the shift of the connectivity profile from C5 to C7 (Figs. 4 and 6). Anterior to the posterior supraprincipal dimple lies C8, which corresponds to the location of area 9 as defined by Walker (1940) and Petrides and Pandya (1994) (Fig. 1E). Both clusters are strongly connected with the retrosplenial cortex, a characteristic of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Morris et al. 1999) (Fig. 6). A subtle difference in retrosplenial connectivity is noted in C7, putative area 8B, as being slightly more anteriorly focused, whereas C8, putative area 9, is more ventral in retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 6) (see Figs. 7 and 10 in Morris et al. 1999; cases 3 and 4 in Pandya and Yeterian 1996; case 5 in Petrides and Pandya 1999). In addition, C7 demonstrates connectivity to area Opt (case 2 in Petrides and Pandya 1999), a pattern that is not pronounced for the more anterior C8. The connectivity of C8 with the ventral premotor cortex does not seem at odds with results from invasive tract-tracing studies and most likely arises due to polysynaptic/network effects (Fig. 6) (see discussion).

From a functional standpoint, area 8B is implicated in conjugate eye movements (Mitz and Godschalk 1989), and ear and eye responses can be invoked (Bon and Lucchetti 1994). Area 9 is implicated in goal-directed orienting behavior (Lanzilotto et al. 2015).

Ventral LFC

All of the clusters documented below were assigned to the ventral premotor group (Fig. 4).

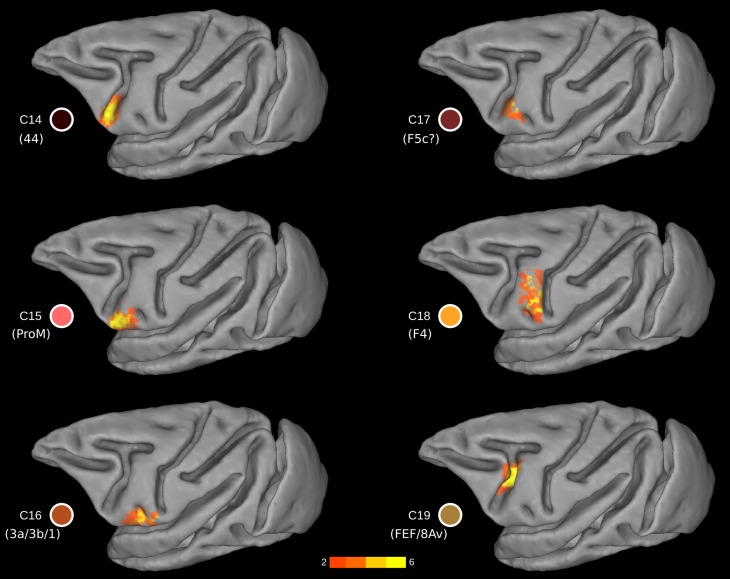

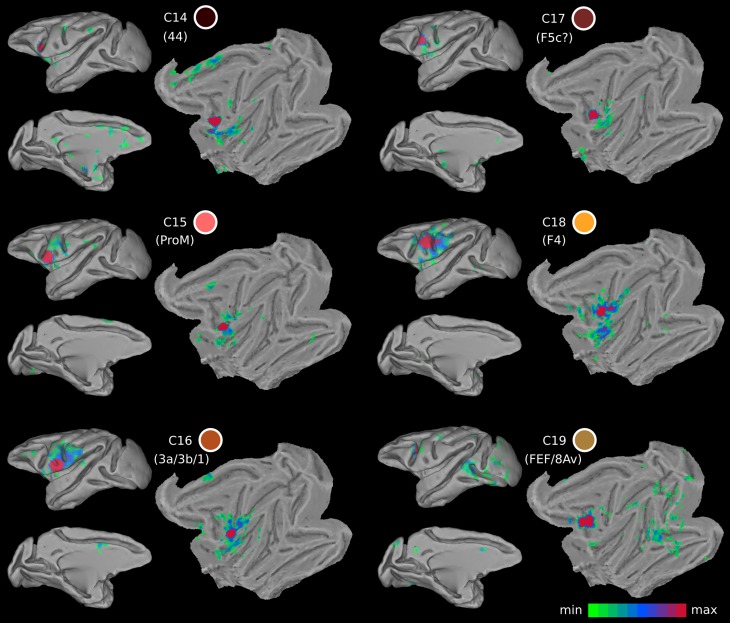

Cluster C14.

This cluster was located at the fundus of the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus (vias; Figs. 1E, 2, and 7) (WCOM x = −20.9, y = 9.0, z = 5.3), where area 44 has been identified (Petrides and Pandya 1994; Petrides et al. 2005), an area distinct from the posteriorly adjacent ventral premotor clusters C15 and C17 and the anteriorly adjacent prearcuate cluster C12. More recent histological analysis has confirmed the presence of area 44 in the fundus of the inferior arcuate sulcus (Belmalih et al. 2009). We conclude that C14 colocalizes very well with what has been identified as area 44 in independent histological analyses of the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus.

Fig. 7.

Probability maps for each ventral LFC cluster. The probability maps are thresholded to include part of the cluster present in at least 2 animals. The color of the clusters corresponds to the color-coding scheme of Fig. 3B. Yellow (orange) colors denote high (low) probability, i.e., presence across animals.

The FC of this region was characterized by strong links to area PFG in the anterior part of the inferior parietal lobule and the adjacent intraparietal cortex, often referred to as area AIP, which is consistent with prior findings from invasive tract-tracing studies (cases 1 and 3 in Frey et al. 2014; case 2 in Petrides and Pandya 2009) (Fig. 8). On the medial part of the hemisphere, FC was observed with the cingulate motor areas and more anterior portions of the cingulate cortex extending around the genu of the corpus callosum. In addition, FC was observed with the insular cortex and the secondary somatosensory region (cases 1 and 2 in Frey et al. 2014) (Fig. 8). A noteworthy discrepancy with knowledge from invasive tract-tracing studies is the lack of FC with the ventral lip of the principal sulcus hosting area 9/46v.

Fig. 8.

Functional connectivity maps of the ventral LFC clusters. The color of the cluster corresponds to the color-coding scheme of Fig. 3B. Shades of red in the functional connectivity maps denote higher t values.

Cluster C15.

Posterior to C14 and immediately anterior to the anterior subcentral dimple (asd), a distinct cluster was uncovered, i.e., C15 (WCOM x = −25.2, y = 6.4, z = 3.9) (Fig. 7). The extent of the cluster was bounded by the imaginary line at the dorsal part of the asd and largely avoided the posterior bank of the vias (Fig. 7). From a topographic point of view, the cluster appears to correspond to area ProM, namely, the proisocortical motor cortex (Barbas and Pandya 1987; Sanides 1968). This area is considered as the proisocortical architectonic step from which subsequent differentiation led to the ventral premotor areas (Barbas and Pandya 1987; Sanides 1970).

The FC of C15 was mostly local (Fig. 8). There was FC with 6VR, 6VC, and the nearby opercular zone including the most anterior part of the insula and also the secondary somatosensory region. The FC seemed to extend into the most ventral part of the central sulcus, possibly involving the orofacial part of the somatosensory region (see ARG case 1 in Cipolloni and Pandya 1999). On the medial wall, FC possibly corresponding with area SMA was observed (see FRT case 1 in Cipolloni and Pandya 1999) (Fig. 8).

Cluster C16.

In the most ventral part of the precentral region, in front of the ventral tip of the central sulcus and posterior to the asd (WCOM x = −26.4, y = 1.2, z = 4.6), a cluster is located that appears to correspond with the precentral extension of the primary somatosensory region (areas 3a, 3b, and 1), as first described by Vogt and Vogt (1919) (Figs. 1 and 7). Somatosensory cortical areas 3, 1, and 2 are primarily found on the postcentral gyrus of the macaque monkey cortex but continue around the most ventral part of the central sulcus and occupy a part of the precentral gyrus as far as the asd. Cluster C16 is consistent with available architectonic maps of the macaque monkey frontal cortex that place this somatosensory region posterior to the asd, whereas proM extends anterior to the asd (Fig. 1).

The local FC of C16 was with nearby precentral ventral somatomotor areas, including the anterior insula, the ventral part of the postcentral gyrus involving areas 3, 1, and 2 (see cases 1, 2, and 3 in Cipolloni and Pandya 1999) (Fig. 8). Moreover, the FC pattern included the orofacial part of area 4, possibly 6VC, and anterior insula and nearby opercular areas, and possibly including the ventral portion of 6VR. Overall, the FC pattern is restricted to ventral precentral and postcentral regions (Fig. 8).

Cluster C17.

This cluster is located on the postarcuate convexity and in the posterior bank of the ventral ramus of the inferior arcuate sulcus (Figs. 1B and 7) (WCOM x = −23.1, y = 5.8, z = 8.4). From a topological point of view, it is reminiscent of area F5 (Matelli et al. 1985) and colocalizes with F5c (Belmalih et al. 2009). The FC pattern of the cluster was predominantly local, including the anterior insular cortex and the ventral orofacial parts of the primary and secondary somatosensory cortex (Fig. 8). These connections are consistent with those reported for the larynx area of the ventral premotor region (Simonyan and Jürgens 2005). In addition, sparse FC was observed with putative SMA in the medial wall and putative area PF in the parietal cortex (Fig. 8), in line with invasive tract-tracing data (see cases 36l and 42l in Gerbella et al. 2011). There are, however, certain noteworthy discrepancies. There was a lack of FC with areas of the granular frontal cortex, contrary to evidence from invasive studies (see cases 36l and 42l in Gerbella et al. 2011). From a functional point of view, this area is implicated in action observation (Nelissen et al. 2005).

Cluster 18.

A separate cluster, C18 (WCOM x = −24.1, y = 0.7, z = 11.5), was observed dorsal to the ads, occupying the ventral part of the precentral region (Figs. 1B and 7). Its topography matches well with the ventral premotor area F4 (Matteli et al. 1985), with the exception that it does not extend dorsally until the spur of the arcuate sulcus and may also include a small part of the dorsal part of premotor area F5. The region around the spur of the arcuate sulcus appears as a distinct cluster (C3), possibly corresponding to the region identified as area 4C by Vogt and Vogt (1919) and Barbas and Pandya (1987). The dorsal border of C18 appears to be the imaginary posterior extension of the principal sulcus (see discussion; Fig. 7).

The FC pattern of cluster C18 involves the rostral inferior parietal lobule, possibly area PF, and the rostral intraparietal sulcus, possibly area VIP, consistent with invasive tract-tracing results (Luppino et al. 1999; Rozzi et al. 2006) (Fig. 8). Area PF is mostly somatosensory related, whereas area VIP seems to include visual and tactile neurons (Geyer et al. 2012). The parietofrontal circuitry formed by F4/F5 and VIP has been suggested to be functionally involved in the execution of movements for reaching and grasping objects in the environment (Geyer et al. 2012). Microstimulation in this part of the cortex elicits mouth and hand movements (Gentilucci et al. 1988; Graziano et al. 1997). Moreover, this area possibly includes neurons responsible for visual space encoding on an arm-centered basis (Graziano et al. 1994).

Cluster C19.

Dorsal to C14 and still within the fundus of the arcuate sulcus, there was a distinct cluster that occupied the dorsal compartment of the inferior arcuate sulcus (dias) (WCOM x = −17.4, y = 4.8, z = 11.1) (Fig. 7). At this level of the inferior arcuate (i.e., posterior to the end of the principal sulcus) lies cortex implicated in oculomotor control (the FEF region) (Bruce and Goldberg 1984; Huerta et al. 1987; Koyama et al. 2004; Moschovakis and Highstein 1994; Petrides et al. 2005; Wardak et al. 2010) (Figs. 1B and 7). However, C19 might also encompass parts of the ventral premotor areas, since it also encompasses parts of the posterior bank of the arcuate sulcus (Fig. 7).

The FC of this cluster is consistent with reports from invasive tract-tracing methods. Strong FC was observed with the intraparietal sulcus and the nearby dorsal prelunate gyrus (area V4) (Huerta et al. 1987; case 3 from Petrides and Pandya 1999; Ungerleider et al. 2008). In addition, the occipitotemporal transition zone, close to the superior temporal sulcus where area MT lies, was also part of the FC signature of this cluster (Huerta et al. 1987) (Fig. 8). Moreover, connectivity with area V1 is demonstrated in an invasive tract-tracing study (Markov et al. 2014), which potentially accounts for the observed V1 FC in our results (Fig. 8). Also note that similar functional properties with the FEF seem to characterize the cortex near the genu of the arcuate sulcus (C13 in Fig. 3B), possibly hosting head movement and large-amplitude saccade-related neurons (Zinke et al. 2015).

DISCUSSION

We have parcellated the LFC of the macaque monkey on the basis of rsfMRI. The resulting clusters, in terms of both their topography and connectivity, are consistent with several aspects of previous parcellation schemes based on cytoarchitectonic analysis (Figs. 1, 3, and 5–9). The current organization scheme based on the intrinsic functional architecture of the macaque monkey LFC provides information relevant to certain debates on LFC organization. We elaborate on these aspects in detail below.

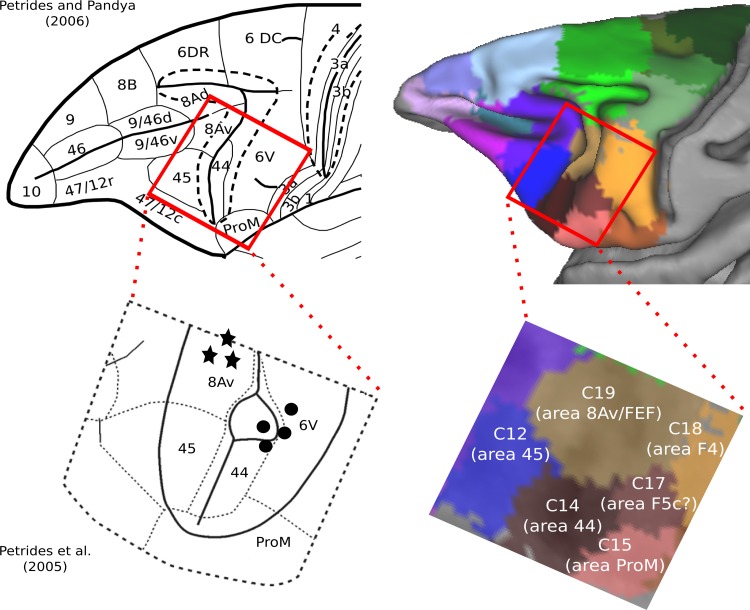

Fig. 9.

Cytoarchitectonic maps of motor and premotor cortical areas. The red box represents the zoomed images of the inferior arcuate sulcus region at bottom. The circles and stars represent approximate locations of orofacial and oculomotor neurons, respectively, as identified by intracortical stimulation (Petrides et al. 2005). Note that the oculomotor and orofacial neurons correspond to distinct connectivity-based clusters identified as putative areas 8Av/FEF and area 44, respectively. Map at top left was modified with permission from Petrides and Pandya (2006). Map at bottom left was adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature, Vol. 435, Petrides M, Cadoret G, and Mackey S, Orofacial somatomotor responses in the macaque monkey homologue of Broca's area, Pages 1235–1238, copyright 2005.

Dorsocaudal Premotor Cortex (Area 6DC/F2): Cortex in the Superior Precentral Dimple and Cortex Within the Spur of the Arcuate Sulcus Constitute Distinct Connectional Divisions

The caudal part of the dorsal premotor cortex is an agranular cytoarchitectonic region that has been referred to as area 6aα by Vogt and Vogt (1919), as area 6DC by Barbas and Pandya (1987), and as area F2 by Matelli et al. (1985). Connectional and functional data suggest an orderly arrangement of somatomotor inputs near the superior precentral dimple related to the leg and arm (e.g., Raos et al. 2003). The ventral limit of this region, however, has been problematic. Findings suggest distinct connectional and functional features of the cortical region within and near the spur of the arcuate sulcus. For instance, the cortex within the spur of the arcuate sulcus is strongly connected with area 45 (case 2 in Petrides and Pandya 2002) and area 8Ad (case 5 in Petrides and Pandya 1999), but neither area 45 nor area 8Ad connects with any part of the cortex dorsal to the spur in area 6DC. In other words, the multisensory prefrontal area 45 and the visuo-auditory prefrontal area 8Ad connect with the cortex of the spur but not with the cortex dorsal to the spur, which receives massive input from somatomotor areas, such as PE (see Petrides and Pandya 1984). Some of these connectional features are reflected in the FC of C4 and C6 (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the cortex within the spur of the arcuate sulcus participates in oculomotor (Koyama et al. 2004) and visuomotor functions (Fogassi et al. 1999; Marconi et al. 2001), suggesting that this part of the cortex is a distinct area. Luppino et al. (2003) have referred to an area just above the spur as F2vr, and this may partly overlap with cluster C6, although C6 lies primarily within the spur and extends slightly above and below it (Fig. 3B). There is also some immunohistochemical evidence consistent with the aforementioned subdivisions (Geyer et al. 2000).

The present analysis provides clear evidence that the cortical region within the spur of the arcuate sulcus is a distinct area, likely corresponding to F2vr (C6 in Fig. 3B). This area is clearly differentiated from other dorsal premotor areas, i.e., cluster C5, corresponding to area 6DR, and cluster C4, corresponding to the dorsal part of area 6DC/F2 (Fig. 3B). These three dorsal premotor divisions exhibit very distinct connectivity profiles (Fig. 6). Notably, despite the fact that, from a topographic point of view, C6/F2vr is a postarcuate cluster, on a connectional basis, it more closely resembles clusters of the prearcuate group (Figs. 4 and 6). In summary, there are at least two distinct areas discernible on a connectional basis within what has been previously defined as F2/6DC.

Intrinsic Resting State Connectivity Distinguishes Two Areas in the Superior Prefrontal Region, Consistent with Areas 9 and 8B, and Places Their Border Along the Posterior Supraprincipal Dimple

The superior frontal region of the monkey, along the midline and anterior to the superior arcuate sulcus, has been considered as a single cytoarchitectonic area, labeled as area 9 in some architectonic maps (Barbas and Pandya 1989; Brodmann 1905; Vogt and Vogt 1919), wheras other maps have considered the caudal part of this region to be a separate area, labeled as area 8B (Petrides and Pandya 1994; Walker 1940) (Fig. 1, A, C, and E). Thus ambiguity still characterizes the organization of the superior frontal region. The present results contribute to this debate by demonstrating the presence of two distinct clusters in the superior frontal region, i.e., C7 (putative area 8B) and C8 (putative area 9), separated by the posterior supraprincipal dimple, consistent with cytoarchitectonic maps (Figs. 1E and 3B). Thus the intrinsic FC supports the distinction of this region into an area 9 and a distinct area 8B, in line with the Walker (1940) and Petrides and Pandya (1994) parcellation schemes.

The two clusters exhibit very similar connectivity profiles that assign both of them to the broad prearcuate group of clusters (Figs. 4 and 6). However, certain notable differences are apparent. C7 (area 8B) exhibits pronounced connectivity with high-level visual related areas in the dorsal prelunate gyrus and area Opt at the junction of the parietal with the occipital region, and the cortex in the caudalmost part of the superior parietal lobule close to the parieto-occipital sulcus. In the temporal lobe, the connectivity is primarily involving the temporal region related to vision (Fig. 6). These findings are consistent with some of the available information about the connectivity of area 8B (Markov et al. 2014; case 2 in Petrides and Pandya 1999). A mild involvement of auditory-related areas in the pattern of connectivity was also observed, which, despite possible contamination due to spatial adjacency with the dorsal part of the inferior temporal cortex, is consistent with invasive tract-tracing findings (Romanski et al. 1999). The aforementioned connectivity pattern was absent from cluster C8 (area 9) (Fig. 6). Thus the connectivity profile of C7 (area 8B) suggests a role in visuo-auditory and motor functions, in line with recent electrophysiological findings (Lucchetti et al. 2008), whereas area 9 might be implicated in goal-directed orientation and monitoring of working memory, as suggested by lesion and microstimulation studies (Lanzilotto et al. 2015; Petrides et al. 1993).

Border Between Dorsal and Ventral Motor/Premotor Areas

A widely accepted two-way division of the premotor areas is the dorsal/ventral division (e.g., Barbas and Pandya 1987; Hoshi and Tanji 2007; Matelli et al. 1985; Matelli and Luppino 2001). Such a division is also supported by a theory postulating a dual origin of the neocortex (Pandya and Yeterian 1990; Sanides 1970). The imaginary caudal extension of the spur of the arcuate sulcus is considered to be the border between the dorsal and ventral premotor areas (Matelli et al. 1985; Sanides 1970) (Fig. 1D). However, on a cyto- and myeloarchitectonic basis, a distinct cortical area is discernible at the cortex caudal to the spur of the arcuate sulcus. This region is characterized by very large neurons in layer V and has been referred to as area 4C by Barbas and Pandya (1987) (Fig. 1B) in accordance with the parcellation of Vogt and Vogt (1919) (Fig. 1A). This is in contrast to the assignment of this region of the cortex to the ventrocaudal premotor cortex, also known as area F4 (Matelli et al. 1985). The present results indicate that, on a connectional basis, a distinct cluster, i.e., C3 (putative area 4C), indeed occupies the cortical region below and posterior to the spur of the arcuate sulcus toward the central sulcus (Figs. 3B and 5). Importantly, its whole brain FC classifies it with the dorsal motor/premotor group (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that the border between the face and arm representation in this lateral region is postulated to mark the border between the ventral and dorsal premotor cortex (Sanides 1970). The border between the face and arm representation in the schema from Matelli and Luppino (2001) is ventral to the spur of the arcuate and nicely corresponds to the border defined by the imaginary caudal part of the principal sulcus (Fig. 1D; see also the microstimulation maps in Gentilucci et al. 1988). In summary, C3 (putative area 4C) appears to be distinct from the ventral motor/premotor region (Figs. 4–7). Consequently, our results place the border between the dorsal and ventral motor/premotor areas in the imaginary caudal extension of the principal sulcus. Further evidence from invasive gold standard tract-tracing methods are needed to establish with more certainty the border between the dorsal and ventral premotor cortex, for instance, by performing the hierarchical clustering currently employed but with connectional data from invasive tract-tracing cases involving the whole dorsoventral extension of the premotor cortex.

A Connectivity-Defined Cluster in the Fundus of the Ventral Compartment of the Inferior Arcuate Sulcus as Putative Area 44

The traditional macroscopic division of the arcuate sulcus is into a superior arcuate sulcus and an inferior arcuate sulcus (Paxinos et al. 2008). Recent examination of the inferior arcuate sulcus in many macaque monkey brains has demonstrated a consistent sigmoid-like shape, which often divides into a clear dorsal and ventral compartment (cases in Frey et al. 2014; cases depicted in Fig. 2 in Petrides and Pandya 2009). A macroscopic division of the inferior arcuate sulcus into a dorsal and a ventral part is also discernible in the F99 template that we have used in the present study (dias and vias in Fig. 2A). Our connectivity-based parcellation demonstrates the presence of two distinct clusters occupying the cortex within the ventral (vias) and dorsal (dias) parts of the inferior arcuate sulcus, respectively. These are clusters C14 (putative area 44) and C19 (putative FEF region) (Figs. 3B, 7, and 9; see also below) and are shown to be clearly distinct from the prearcuate clusters C12 and C13 and the postarcuate clusters C15, C17, and C18 (Fig. 3B).

In the human brain, immediately anterior to the ventral part of the premotor cortex (area 6), which is involved with the control of the orofacial musculature, lies a distinct area known as 44 that has been shown to be a critical component of the region involved in language production (Broca's region). Earlier attempts to identify a homologue of area 44 had considered that the macaque monkey area F5, which is found on the postarcuate cortical region just caudal to the inferior arcuate sulcus, and its anterior extension (F5a) into the posterior bank of the inferior arcuate sulcus, may be a homologue of area 44 in the human brain (Geyer et al. 2012). These suggestions were largely driven by an attempt to relate the classical mirror neuron findings in premotor area F5 to the development of language. On the basis of a cytoarchitectonic comparison of human and macaque monkey cortex, Petrides and Pandya (1994) considered a region immediately anterior to premotor area F5 (also referred to as 6VR) in the depth of the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus as a homologue of area 44 of the human brain. Later, this region was shown to be involved with the orofacial musculature on the basis of microstimulation and single-neuron recording (Petrides et al. 2005). The connectivity of this region in the macaque monkey was recently clarified by invasive anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing studies (Frey et al. 2014; Petrides and Pandya 2009).

The results of the present study clearly demonstrate the presence of a distinct cluster in the fundus of the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus, namely, C14 (Figs. 3B and 7), which is clearly differentiated from the adjacent anterior prearcuate cluster (C12, possibly corresponding to area 45) and two distinct clusters on the posteriorly adjacent ventral premotor cortex, namely, clusters C15 and C17, which appear to correspond to two distinct postarcuate areas previously referred to as putative area ProM, 6bβ in the terminology of Vogt and Vogt (1919), and a distinct part of the ventral part of premotor area F5/6VR that appears to correspond with area 6bα of Vogt and Vogt (1919), respectively. Hence, our results corroborate previous histological findings by demonstrating, on a connectional basis, the presence of a distinct cluster within the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus colocalizing well with what has been previously described as area 44.

The FC of C18 in the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus corresponds largely with that examined with anterograde and retrograde methods in the macaque monkey (Frey et al. 2014; Petrides and Pandya 2009). The discovery of area 44 in the depth of the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus of the macaque monkey has generated a debate as to the prelinguistic role of this area and its recruitment for the control of certain aspects of language production with the evolution of language in the human brain (Petrides, 2006). Recently, Coude et al. (2011) demonstrated neurons in the ventral part of the premotor cortex that are involved in the voluntary control of phonation, an important component in the neural machinery necessary for the emergence of language. It has been argued that area 44 is a specialized area that lies between the ventral premotor region that controls orofacial and manual action and prefrontal areas involved in the controlled retrieval of information from memory and may thus have been in a privileged position to mediate between information retrieval and communicative action. Retrieval of information necessary to respond to a specific need would be necessary before action could be organized to convey the subject's communicative response. Thus a prelinguistic neural circuit centered around area 44 might have been ideally suited to the needs of language expression as language evolved.

Immediately posterior to C14 within the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus, we identified two separate distinct clusters, namely, C15 and C17 (Figs. 3B and 7). C15 appears to correspond well with area ProM. C17 appears to correspond with area F5c (Belmalih et al. 2009), and electrophysiological data in the macaque monkey has suggested that this ventral oblique strip of cortex may represent the laryngeal/vocal musculature part of the cortex (Hast et al. 1974; Simonyan and Jürgens 2005).

In summary, our present findings, in conjuction with earlier anatomical and physiological research in the macaque monkey, suggest the existence of an orofacial dominated region in the ventral part of the inferior arcuate sulcus (C14/area 44) that is surrounded posteriorly by a strip of cortex that represents the orofacial/vocal musculature (C17/area F5c) and posteroventrally by another strip, that is, C15 (area ProM).

A Connectivity-Defined Cluster in the Fundus of the Dorsal Compartment of the Inferior Arcuate Sulcus as Putative Area 8Av/FEF

In the dorsal part of the inferior arcuate sulcus, another cluster was identified on the basis of resting-state FC, namely, C19 (putative FEF) (Figs. 3B, 7, and 9). This area appears connected with vision-related areas, in sharp contrast to the connectivity of C14 (putative area 44), which exhibits a somatomotor profile (Fig. 8). It is noteworthy that this sharp connectivity distinction is reflected in the effects of intracortical microstimulation: neurons in the fundus of the ventral ramus of the inferior arcuate sulcus elicit orofacial responses, whereas neurons in the cortex in the dorsal ramus of inferior arcuate sulcus, mostly located in its rostral bank, elicit oculomotor responses (Petrides et al. 2005) (Fig. 9). Although traditional accounts often link the FEF region with granular prefrontal area 8Av, there is strong evidence that, on a microstimulation basis, this region lies in the fundus and anterior bank of the arcuate region, a region where a transition between agranular area 6 and the fully granular cortex of the prearcuate cortex takes place. Furthermore, functional neuroimaging evidence in the monkey (Koyama et al. 2004; Savaki et al. 2015) indicates that the premotor agranular cortex in the caudal bank of the arcuate sulcus is also involved in oculomotor function. Such topological characteristics of the FEF are consistent with the location of C19.

In summary, the parcellation results of the present study contribute to a resolution of ambiguities concerning the ventral extent of the oculomotor-related cortex within the inferior arcuate sulcus, indicating the presence of two areas with distinct connectional profiles that occupy distinct macroscopic subdivisions of the inferior arcuate sulcus. Thus the macroscopic distinction, vias and dias, might be used for an approximation of the borders of these two areas. Moreover, the current connectivity-based map, within the limitations of rsfRMI, offers putative borders of these two areas with the adjacent post- and prearcuate regions, as well as their whole brain connectivity (Figs. 7–9).

Variability of Cortical Areas

The current approach offers a tentative estimation of the variability of the putative cortical areas underlying the currently identified clusters. Because rsfMRI is limited in terms of resolution and specificity, the indicated variability can be seen as an upper bound of the true neurobiological variability. Hence, the variability based on invasive histological measurements is expected to be lower than the variability based on our FC parcellation, which is already low for certain cortical areas.

Limitations and Perspectives

Connectivity, estimated from rsfMRI data, does not provide the level of detail of gold standard invasive tract-tracing techniques. In addition, connectivity maps estimated from rsfMRI might include areas between which no direct anatomical connectivity exists, reflecting polysynaptic connectivity (Adachi et al. 2012; Goñi et al. 2014). A much needed next step is to assess quantitatively the degree of correspondence of FC and connectivity estimated with invasive tract-tracing methods (see Miranda-Dominguez et al. 2014 for a first attempt of such quantification). Despite the limitations in specificity and resolution of the method, the present results inform current debates about the organization of the LFC by providing evidence of connectional divisions of the LFC. The precise boundaries, on a cytoarchitectonic basis, of these divisions and their precise connectivity pattern can be uncovered by quantitative cytoarchitectonic analysis (e.g., Mackey and Petrides 2010). Moreover, diffusion imaging and tractography can also be employed to perform an in vivo connectivity-based parcellation. Employing diffusion imaging in the human cortex has been demonstrated to lead to largely converging results with rsfMRI (Johansen-Berg et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2010). We thus expect that given similar parcellation methods, the two modalities will result in converging parcellations.

The clusters currently uncovered could consist of further subdivisions. For instance, C5/area F7/6DR is usually treated as nonhomogenous, consisting of a supplementary eye field and a nonsupplementary eye field zone (Luppino et al. 2005). The organization of the cortex could be represented as a hierarchy, spanning several spatial scales (Meunier et al. 2010). Indeed, broader divisions of the LFC have been found using the rsfMRI data (Hutchison and Everling 2013). Higher spatial resolution alongside with advancements in clustering approaches, despite substantial challenges (see Lancichinetti and Fortunato 2011), could potentially offer a more fine grained parcellation, moving toward lower spatial levels of the LFC organization.

Signal contamination between adjacent banks of sulci, such as the dorsal and ventral bank of the principal sulcus, render problematic the accurate parcellation of cortical areas within sulci. Such limitations might be circumvented with higher spatial resolution during the rsfMRI acquisition. The dorsal and ventral LFC clusters that are the focus of the current study are largely not influenced by such signal contamination, with C19 being an exception since it might also encompass parts of the ventral premotor areas in the posterior bank of the arcuate sulcus.

Conclusions

We investigated the intrinsic functional architecture of the LFC of the macaque to elucidate current debates on its architecture. Within the dorsal LFC, we demonstrate that 1) the posterior supraprincipal dimple constitutes the border between two areas; 2) area 6DC/F2 contains two distinct connectivity-defined areas; and 3) a distinct area exists around the spur of the arcuate at the border of the dorsal/ventral division of the LFC. Our results within the ventral LFC clearly demonstrate the presence of a putative area 44, with a somatomotor/orofacial connectional signature. This area is located in the fundus of the vias and is differentiated from premotor and prearcuate clusters, bounded dorsally by a distinct cluster with an oculomotor connectional signature, identified as putative FEF and located in the dias. Both of these areas were discernible from adjacent premotor clusters. The current map can be used for future cross-species examination of putative homologues in the human LFC with the aid of the same modality, namely, rsfMRI.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.G., D.S.M., P.S., and M.P. conceived and designed research; A.G. analyzed data; A.G., P.S., and M.P. interpreted results of experiments; A.G. prepared figures; A.G., M.P., and D.S.M. drafted manuscript; A.G., P.S., R.M.H., S.E., M.P., and D.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; A.G., P.S., R.M.H., S.E., M.P., and D.S.M. approved final version of manuscript; R.M.H. and S.E. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laura Wallor for assistance in preparing Fig. 1.

Preprint available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/058776.

REFERENCES

- Adachi Y, Osada T, Sporns O, Watanabe T, Matsui T, Miyamoto K, Miyashita Y. Functional connectivity between anatomically unconnected areas is shaped by collective network-level effects in the macaque cortex. Cereb Cortex 22: 1586–1592, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiez C, Petrides M. Anatomical organization of the eye fields in the human and non-human primate frontal cortex. Prog Neurobiol 89: 220–230, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambault PS, Ferrari-Toniolo S, Battaglia-Mayer A. Online control of hand trajectory and intention in the parietofrontal system. J Neurosci 31: 742–752, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Hutchison RM, Gati JS, Menon RS, Everling S. Functional connectivity patterns of medial and lateral macaque frontal eye fields reveal distinct visuomotor networks. J Neurophysiol 109: 2560–2570, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakola S, Passarelli L, Gamberini M, Fattori P, Galletti C. Cortical connectivity suggests a role in limb coordination for macaque area PE of the superior parietal cortex. J Neurosci 33: 6648–6658, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, Pandya DN. Architecture and frontal cortical connections of the premotor cortex (area 6) in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 256: 211–228, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, Pandya DN. Architecture and intrinsic connections of the prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 286: 353–375, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmalih A, Borra E, Contini M, Gerbella M, Rozzi S, Luppino G. Multimodal architectonic subdivision of the rostral part (area F5) of the macaque ventral premotor cortex. J Comp Neurol 512: 183–217, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel VD, Guillaume JL, Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J Stat Mech 8: P10008, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bon L, Lucchetti C. Ear and eye representation in the frontal cortex, area 8b, of the macaque monkey: an electrophysiological study. Exp Brain Res 102: 259–271, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. Beiträge zur histologischen Lokalisation der Grosshirnrinde. Dritte Mitteilung: Die Rindenfelder der niederen Affen. J Psychol Neurol 4: 177–226, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce CJ, Goldberg ME. Physiology of the frontal eye fields. Trends Neurosci 7: 436–446, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Posterior parietal cortex in rhesus monkey: II. Evidence for segregated corticocortical networks linking sensory and limbic areas with the frontal lobe. J Comp Neurol 287: 422–445, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolloni PB, Pandya DN. Cortical connections of the frontoparietal opercular areas in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 403: 431–458, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coude G, Ferrari PF, Roda F, Maranesi M, Borelli E, Veroni V, Monti F, Rozzi S, Fogassi L. Neurons controlling voluntary vocalization in the macaque ventral premotor cortex. PLoS One 6: e26822, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogassi L, Raos V, Franchi G, Gallese V, Luppino G, Matelli M. Visual responses in the dorsal premotor area F2 of the macaque monkey. Exp Brain Res 128: 194–199, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato S, Barthélemy M. Resolution limit in community detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 36–41, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S, Mackey S, Petrides M. Cortico-cortical connections of areas 44 and 45B in the macaque monkey. Brain Lang 131: 36–55, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Mushiake H, Tanji J. Rostrocaudal distinction of the dorsal premotor area based on oculomotor involvement. J Neurophysiol 83: 1764–1769, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilucci M, Fogassi L, Luppino G, Matelli M, Camarda R, Rizzolatti G. Functional organization of inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey. I. Somatotopy and the control of proximal movements. Exp Brain Res 71: 475–490, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbella M, Belmalih A, Borra E, Rozzi S, Luppino G. Multimodal architectonic subdivision of the caudal ventrolateral prefrontal cortex of the macaque money. Brain Struct Funct 212: 269–301, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbella M, Belmalih A, Borra E, Rozzi S, Luppino G. Cortical connections of the anterior (F5a) subdivision of the macaque ventral premotor area F5. Brain Struct Funct 216: 43–65, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Zilles K, Luppino G, Matelli M. Neurofilament protein distribution in the macaque monkey dorsolateral premotor cortex. Eur J Neurosci 12: 1554–1566, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Luppino G, Rozzi S. Motor cortex. In: The Human Nervous System (3rd ed), edited by Mai JK, Paxinos G. Amsterdam:0 Academic, 2012, p.1012–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Good BH, De Montjoye YA, Clauset A. The performance of modularity maximization in practical contexts. Phys Rev E 81: 046106, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goñi J, Van den Heuvel MP, Avena-Koenigsberger A, Velez de Mendizabal N, Betzel RF, Griffa A, Hagmann P, Corominas-Murtra B, Thiran JP, Sporns O. Resting-brain functional connectivity predicted by analytic measures of network communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 833–838, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulas A, Uylings HB, Stiers P. Unravelling the intrinsic functional organization of the human lateral frontal cortex: a parcellation scheme based on resting state fMRI. J Neurosci 32: 10238–10252, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano M, Yap G, Gross C. Coding of visual space by premotor neurons. Science 266: 1054–1057, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano M, Hu X, Gross C. Visuospatial properties of ventral premotor cortex. J Neurophysiol 77: 2268–2292, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hast MH, Fischer JM, Wetzel AB, Thompson VE. Cortical motor representation of the laryngeal muscles in Macaca mulatta. Brain Res 73: 229–240, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E, Tanji J. Integration of target and body-part information in the premotor cortex when planning action. Nature 408: 466–470, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E, Tanji J. Distinctions between dorsal and ventral premotor areas: anatomical connectivity and functional properties. Curr Opin Neurobiol 17: 234–242, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Krubitzer LA, Kaas JH. Frontal eye field as defined by intracortical microstimulation in squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, and macaque monkeys. II. Cortical connections. J Comp Neurol 265: 332–361, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Leung LS, Mirsattari SM, Gati JS, Menon RS, Everling S. Resting-state networks in the macaque at 7T. Neuroimage 56: 1546–1555, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Gallivan JP, Culham JC, Gati JS, Menon RS, Everling S. Functional connectivity of the frontal eye fields in humans and macaque monkeys investigated with resting-state fMRI. J Neurophysiol 107: 2463–2474, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison RM, Everling S. Broad intrinsic functional connectivity boundaries of the macaque prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage 88: 202–211, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]