Abstract

Following synthesis, RNA can be modified with over 100 chemically distinct modifications, which can potentially regulate RNA expression post-transcriptionally. Pseudouridine (Ψ) was recently established to be widespread and dynamically regulated on yeast mRNA, but less is known about Ψ presence, regulation, and biogenesis in mammalian mRNA. Here, we sought to characterize the Ψ landscape on mammalian mRNA, to identify the main Ψ-synthases (PUSs) catalyzing Ψ formation, and to understand the factors governing their specificity toward selected targets. We first developed a framework allowing analysis, evaluation, and integration of Ψ mappings, which we applied to >2.5 billion reads from 30 human samples. These maps, complemented with genetic perturbations, allowed us to uncover TRUB1 and PUS7 as the two key PUSs acting on mammalian mRNA and to computationally model the sequence and structural elements governing the specificity of TRUB1, achieving near-perfect prediction of its substrates (AUC = 0.974). We then validated and extended these maps and the inferred specificity of TRUB1 using massively parallel reporter assays in which we monitored Ψ levels at thousands of synthetically designed sequence variants comprising either the sequences surrounding pseudouridylation targets or systematically designed mutants perturbing RNA sequence and structure. Our findings provide an extensive and high-quality characterization of the transcriptome-wide distribution of pseudouridine in human and the factors governing it and provide an important resource for the community, paving the path toward functional and mechanistic dissection of this emerging layer of post-transcriptional regulation.

Following synthesis, RNA can be modified with over 100 chemically distinct modifications (Machnicka et al. 2013), each catalyzed by one or more dedicated and often highly conserved (Anantharaman et al. 2002) enzymes. In an analogous manner to modifications occurring post-synthesis on proteins (e.g., phosphorylation, ubiquitination) or on DNA (e.g., 5-methylcytosine), chemical modifications on RNA—and particularly within mRNA—harbor the potential of regulating the complex life cycle of mRNAs.

Pseudouridine (Ψ), the first RNA modification to be uncovered, is also the most ubiquitous modification on RNA. Ψ formation is catalyzed by diverse pseudouridine synthases (PUSs), which break the carbon-nitrogen bond of uridine and create a carbon-carbon bond by attaching the C5 position of the cleaved uridine to the ribose (Charette and Gray 2000). PUSs can either act in a site-specific manner, by directly recognizing their substrates, or can be guided to their targets via H/ACA box snoRNAs (Charette and Gray 2000; Spenkuch et al. 2014; McMahon et al. 2015).

For decades, Ψ was studied only within a very limited set of RNAs (almost exclusively in tRNA, rRNA, and snRNA) whose high expression levels had facilitated the biochemical identification of Ψ. Recently, three groups, including our own, have established methodologies for mapping Ψ in a transcriptome-wide manner, relying on a conceptually similar approach, of generating an RNA-seq library following pretreatment of RNA with a N-cyclohexyl-N′-(β-[N-methylmorpholino]ethyl)carbodiimide p-toluenesulfonate salt (CMC) which selectively binds to Ψ and presents a barrier to reverse-transcription. Following library generation and sequencing, modified sites are characterized by a pileup of reads beginning 1 nt downstream from the Ψ site. These studies have revealed that, rather than being present only on tRNA, rRNA, and snRNA, Ψ is widespread, and dynamically regulated, on yeast mRNA (Carlile et al. 2014; Lovejoy et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014), where it is catalyzed by at least four distinct PUSs.

Two of these groups (Carlile et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014), along with a later study (Li et al. 2015), mapped Ψ in human samples, where they collectively identified thousands of putative Ψ sites. However, because measurements of Ψ rely on the presence of reads at a single nucleotide (and cannot be aggregated over an entire gene, as for example, in RNA-seq), ultradeep coverage is required to obtain robust and accurate measurements for sites within mRNAs (Schwartz et al. 2014). The limitations in achieving such depth for the majority of sites within mRNA can give rise to a substantial number of both false negatives and false positives (see also below).

Obtaining accurate maps of Ψ in the human transcriptome is crucial for addressing fundamental questions pertaining to human mRNA pseudouridylation and its potential roles in post-transcriptional regulation of RNA. Key questions of interest in this context are understanding which of the 13 PUSs in human have which mRNA substrates, and which is of particular interest, as mutations in at least three human PUSs underlie various diseases, including mitochondrial myopathies and intellectual disability (Heiss et al. 1998; Bykhovskaya et al. 2004; Fernandez-Vizarra et al. 2009; Shaheen et al. 2016). An additional critical question is unravelling the sequence and structural elements collectively defining the specificity of enzymes toward their targets. Elucidation of the code governing catalysis of Ψ at their targets is critical to allowing interpretation of how mutations, such as in a disease-related context, impact mRNA pseudouridylation. Understanding substrate specificity can further provide important insight into how the presence and levels of Ψ at individual sites can be differentially tuned between different conditions and cell types.

Here, we sought to obtain high-confidence maps of Ψ on mammalian mRNA, to identify the main PUSs catalyzing Ψ formation, and to understand the factors governing their specificity toward their targets. We established a computational pipeline for integrating >2.5 billion reads from 30 available pseudouridine mapping experiments in human, to identify reproducibly detected putative Ψ sites. These maps, complemented with genetic perturbations, allowed us to uncover TRUB1 and PUS7 as the two key PUSs collectively accounting for pseudouridylation at ∼60% of high-confidence pseudouridylation sites in human and to computationally model the sequence and structural elements governing the specificity of TRUB1. We validate these maps and the inferred specificity of TRUB1 using massively parallel reporter assays (MPRA) in which we monitor Ψ levels at thousands of synthetically designed sequence variants comprising either wild-type (WT) sequences surrounding pseudouridylation targets or carefully designed mutants perturbing the RNA sequence and structure. Our study broadly and extensively characterizes the transcriptome-wide distribution of pseudouridine on mammalian mRNA and the key enzymes catalyzing its formation and provides high-quality maps of Ψ in mammals to the community. We expect that these will facilitate functional and mechanistic dissection of this emerging layer of post-transcriptional regulation.

Results

Identification and integration of putative Ψ sites from multiple data sets

To characterize the Ψ landscape in human mRNA, we began by re-analyzing >2.5 billion reads (or read pairs) from three available data sets harboring transcriptome-wide mappings of Ψ in human cell lines. The first data set, previously produced by us (Schwartz et al. 2014), comprised eight samples from HEK293 cells and fibroblasts. The second data set, by Carlile et al. (2014), comprised nine samples in HeLa cells grown under WT or serum starvation conditions. The third data set, by Li et al. (2015), comprised 13 samples in HEK293 cells under a range of conditions/perturbations.

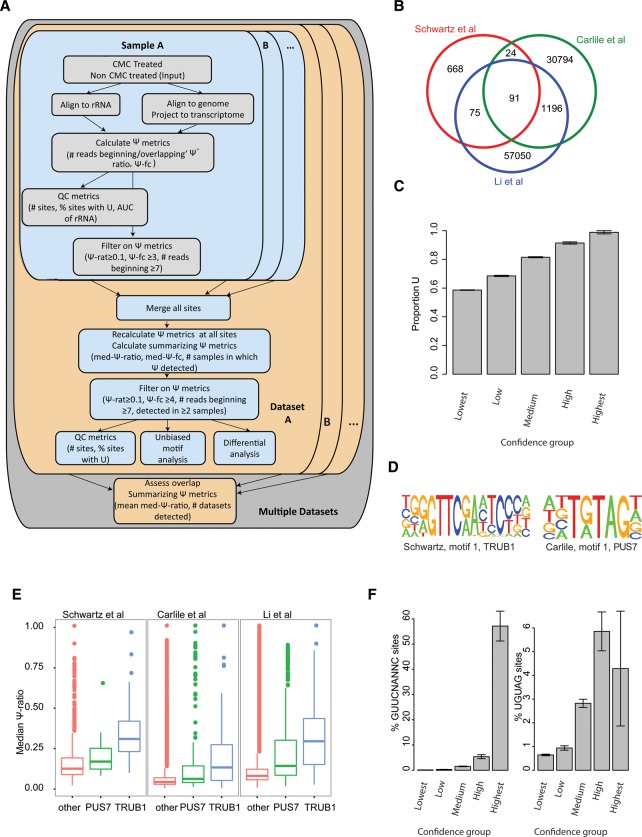

We generated a computational pipeline to allow analysis, evaluation, and integration of Ψ mappings from these diverse samples across multiple data sets (Fig. 1A; Methods). This pipeline implements a three-tiered analysis, beginning with an analysis of CMC-treated and untreated sample pairs (sample level), followed by integration of multiple sample pairs (data set level). As a final step, information from multiple data sets is integrated. Ψ level estimates and QC metrics are derived at the different levels, including: (1) the Ψ-ratio, quantifying the number of reads in which reverse-transcription terminated at the site divided by the overall number of reads overlapping it; in the presence of sufficient sequencing depth, this ratio is in excellent correlation with actual Ψ stoichiometries (Schwartz et al. 2014); (2) quality of Ψ mapping, estimated based on strength of signal at known Ψ sites in rRNA, measured via the area under the curve (AUC) value capturing the tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity; and (3) a lower bound on the false detection rate (mFDR), estimated by assessing the proportion of sites passing the thresholds at each level that do not harbor a uridine and hence are, by definition, false positives.

Figure 1.

Detection and sequence analysis of Ψ sites across experimental data sets. (A) Scheme outlining computational approach for detection and integration of Ψ sites from multiple samples and data sets. For each sample pair, consisting of CMC-treated and untreated (input) samples in a specific data set, genomic mappings of reads are first cast onto transcriptome coordinates, following which a set of Ψ metrics is computed for each site, comprising the total number of reads terminating and overlapping the site in the input and treated samples, the Ψ-ratio (# terminating/# overlapping) for each of the samples, and the Ψ fold-change (Ψ-ratio treated/Ψ-ratio untreated). Sites surpassing thresholds in terms of coverage, Ψ-ratio and Ψ fold-change are flagged as putative Ψ sites. In parallel, QC metrics for the sample pair are derived, the most informative of which we found to be (1) area under the ROC curve (AUC) values capturing the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity when overlapping the ranked set of detected sites (ordered based on Ψ-ratio) in the 18S rRNA with the known set of modified sites, and (2) % of putative pseudouridylated sites harboring a U at detected site. For each data set (harboring multiple sample pairs), all sites detected in any of the positions are first concatenated, following which Ψ metrics are recalculated for all sites across all samples, in addition to summarizing metrics including the median Ψ-ratio and the number of samples in which evidence for pseudouridylation exists. Stringent filters are applied at this level, to identify sites that are reproducibly identified at high Ψ levels. (B) Venn diagram showing extent of overlap between detected sites across the three analyzed data sets. (C) Fraction of putative Ψ sites harboring a U at the detected position (y-axis) plotted as a function of confidence group, capturing both the number of samples and data sets in which the putative position was detected. The fraction of sites not harboring a U is considered a lower bound on the false detection rate. (D) Sequence logos of the top motifs identified in the Schwartz et al. and Carlile et al. data sets are depicted. (E) Median Ψ-ratios for sites harboring a PUS7, TRUB1, or other motif across the three data sets. (F) Fraction of putative pseudouridylated sites comprising a TRUB1 (left) and PUS7 (right) motif, plotted for each confidence group (see panel C).

Application of this pipeline to the three above-defined data sets identified varying numbers of sites across the data sets, with 858, 32,105 and 58,412 sites identified in the data sets of Schwartz et al., Carlile et al., and Li et al., respectively (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S1A; Supplemental Table S1). Across at least two data sets, 1386 sites were shared, 91 of which were common to all three (Fig. 1B). This relatively low overlap likely reflects, in part, technical aspects, including the varying quality of the data sets as assessed using the known rRNA sites (Supplemental Fig. S1A,B) and variability in read distribution stemming from low read-counts that can give rise to a high false discovery rate at all levels of analysis (Supplemental Fig. S1A) and to both false positives and false negatives (Supplemental Fig. S1C,D). In addition, the low overlap may also reflect biological variability between the different samples, which originate from distinct cell lines and/or growth conditions.

Reassuringly, our analyses indicate that the false detection rate is dramatically reduced at sites that are reproducibly detected across multiple samples and data sets. To evaluate this, we divided all sites into one of five confidence bins: “lowest,” if the site was detected in two samples in a single data set; “low,” if it was detected in three samples in a single data set; “medium,” if it was detected in >3 conditions in a single data set; “high,” if it was detected in two data sets; and “highest,” if it was detected across all three data sets. Examining the proportion of sites harboring a U as a lower boundary on false detection rate, we found that, while in the lowest bin >40% of the sites had a nucleotide other than a U, in the “high” confidence bin, 1184/1295 (91.4%) harbored a U, and in the “highest” bin, all but a single site (90/91, 99%) harbored a U (Fig. 1C). Confidence in these consistently identified positions in the “highest” bin was further boosted by using known sites in tRNAs as a positive control: The “highest” bin comprised 14 positions in tRNA, 13 of which were at positions known to undergo pseudouridylation (positions 14, 28, and 55 of various tRNAs), and one (at position 54 of valine tRNA) likely reflects a “stuttering” effect of RT termination at CMC-bound sites (Bakin and Ofengand 1998). Thus, the reproducibly detected sites represent a stringently defined subset of pseudouridylation sites with a very low false positive rate (albeit presumably with a high false negative rate), providing the opportunity to explore and characterize this high-confidence subset of the human pseudouridylation landscape.

Two dominant sequence motifs are present at Ψ sites

PUSs are guided to their targets via specific sequence and/or structural motifs. As a first step toward uncovering which PUSs catalyze Ψ on mammalian mRNA, we focused on deciphering the sequence and structural motifs in the data set of Ψ positions. We developed a clustering procedure that identifies, ranks, and clusters sequence motifs based on their prevalence in a sample and on the pseudouridylation levels of targets harboring those motifs, such that motifs are ranked higher with increasing frequency and pseudouridylation levels (Methods).

Applying this unbiased approach to each of the data sets revealed two motifs to be the highest ranking motifs across all data sets. The first motif consisted of a GUUCNANNC core and strongly resembles the target of pseudouridylation by yeast Pus4, and the second consisted of a UGUAG core, strongly resembling the targets of yeast Pus7 (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Fig. S1E). We refer to these motifs as TRUB1 and PUS7 motifs, respectively, based on the human homologs of these proteins, the functionality of which we confirm below. Across all three data sets, sites harboring a TRUB1 and PUS7 motif were pseudouridylated at significantly higher levels than at sites lacking these motifs, with highest levels achieved at TRUB1 motifs (Fig. 1E). Importantly, both TRUB1 and PUS7 motifs were increasingly enriched in higher confidence bins (Fig. 1F), with 39 of 70 (56%) Ψ sites on mRNA in the “highest” confidence bin harboring a TRUB1 motif, and 3/70 (4%) sites harboring a PUS7 motif, compared to <1% of both targets in the “lowest” confidence bin. Thus, TRUB1 and PUS7 motifs collectively account for 60% of all robustly identified sites in mRNA, establishing them—and in particular TRUB1 motifs—as the dominant pseudouridylated substrates in human mRNA.

Characterization and modeling of TRUB1 substrates

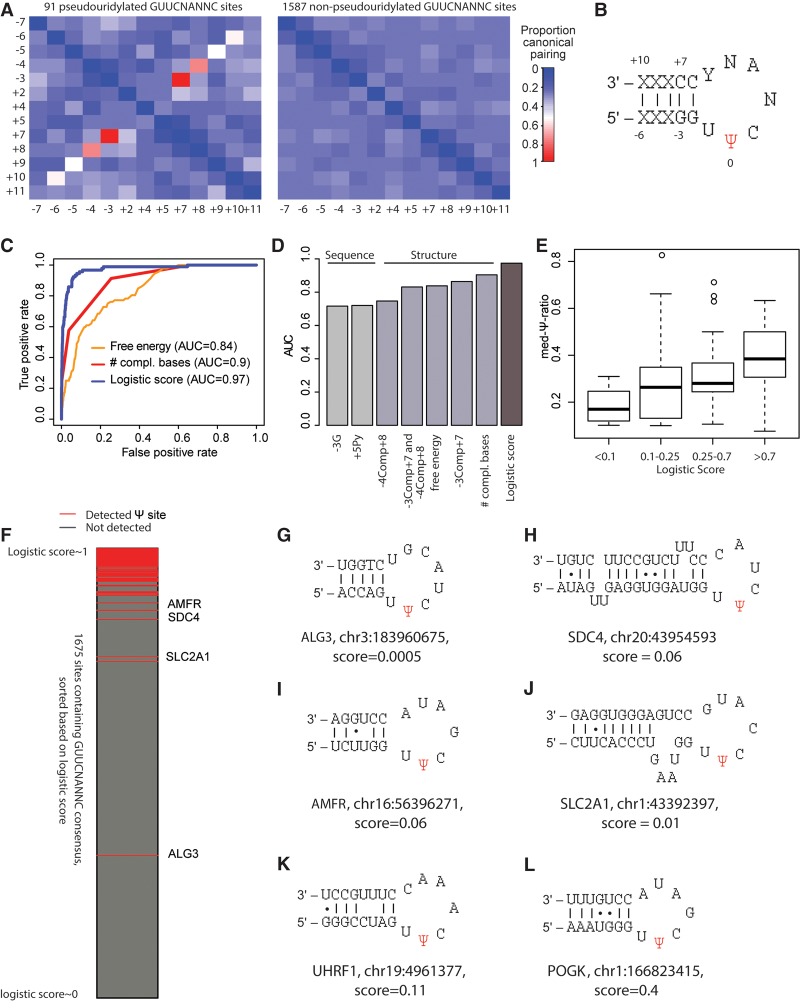

Why is Ψ detected at only a fraction of the 14,381 sites harboring a TRUB1 consensus sequence in the human transcriptome? And what determines Ψ levels at TRUB1 targets? To address these questions, we assembled a data set of 91 test sites harboring the stringently defined TRUB1 consensus sequence with evidence of pseudouridylation in HEK293 cells based on the Schwartz et al. data set. In addition, we defined a data set of 1587 control sites that (1) harbored the TRUB1 consensus sequence, (2) lacked evidence of pseudouridylation in the Schwartz et al. data set, and (3) had at least 30 reads overlapping them, to ensure that lack of detection of Ψ did not reflect a lack of data. We then compared the test and control sites in terms of sequence and secondary structure features. Strikingly, we found that within the test sites, positions −3 to −6 with respect to the Ψ site, are highly likely to be complementary to positions +7 to +10, respectively (Fig. 2A). This effect was absent in the control sites. Along with invariable position −2 (G) which is complementary to invariable position +6 (C), the test sites are thus predicted to give rise to a hairpin, consisting of a 5-bp stem and a 7-bp loop, with the Ψ site being the second base in the loop (Fig. 2B). Of note, this local secondary structure matches the one typically present at position 55 of tRNA, where Ψ is catalyzed by Pus4, the yeast TRUB1 homolog (Becker et al. 1997; Gu et al. 1998; Hoang and Ferré-D'Amaré 2001). Thus, our data strongly suggest that this stem and loop structure can form on mRNA and is sufficient for mRNA pseudouridylation.

Figure 2.

Characterization and modeling of TRUB1 sites. (A) Heat map depicting proportion of sites comprising a TRUB1 consensus sequence in which the indicated pairs of positions (labeled with respect to the Ψ position) are complementary to each other. This analysis was performed separately for 92 sites harboring a GUUCNANNC motif with evidence of pseudouridylation in HEK293 cells (Methods) and for 1587 control sites harboring the same consensus sequence but lacking evidence of pseudouridylation. Only varying positions are depicted, hence excluding positions −2, −1, 0, 1, 3, and 6. (B) Hairpin predicted to form based on complementarity identified in A. (C) Receiver-operator curves (ROCs) for distinct models predicting the likelihood of a site being a TRUB1 substrate based either on predicted free energy of secondary structure calculated for a sequence of 24 bases surrounding the putative Ψ site, the number of complementary bases in the stem (a value from 1 to 4), or a linear combination of all of the features shown in D. (D) Area under the ROC curve (AUC) values shown for prediction of pseudouridylation status based on indicated features. (E) Distribution of Ψ-ratios across four classes of sites, divided according to the logistic regression-based probability of being pseudouridylated. (F) All 1679 TRUB1 consensus-containing sites with sufficient coverage are ranked based on their logistic score and color-coded as indicated based on whether pseudouridylation was detected experimentally. (G–L) Predicted secondary structure of indicated sites that harbor a TRUB1 consensus sequence and are reproducibly detected as pseudouridylated, yet obtain very low logistic regression-based scores of undergoing pseudouridylation. Canonical base pairs are joined by a line; noncanonical G-U pairs are joined by a dot.

On the basis of this observation, we defined several variables capturing the secondary structure, including the predicted free energy of the binding and the number of bases undergoing base-pairing, in addition to individual binary variables capturing the base-pairing propensity between each set of positions in the stem (equaling 1 if the positions form C/G or A/T pairs, 0 otherwise) (Methods). Further comparison between the test and control sites revealed additional sequence characteristics of pseudouridylated sites including a preference for a G at position −3 and for a pyrimidine at position +5.

These features, derived solely based on sequence and predicted secondary structure, are sufficient to provide accurate predictions on whether a site will undergo pseudouridylation. A logistic regression model integrating these features and trained to predict pseudouridylation state attained an AUC value of 0.97 (where 1 reflects perfect separation between targets and nontargets, whereas 0.5 reflects random separation), indicating that the model is both highly sensitive and specific (Fig. 2C). The features capturing the secondary structure were the most informative ones, among which the most informative feature was the number of complementary bases in the stem, which in itself was sufficient for training a classifier with an AUC of 0.9 (Fig. 2D).We further found that, although the model was designed to predict pseudouridylation state, the probabilities assigned by the model correlated with pseudouridylation levels, such that sites with higher likelihoods of being pseudouridylated had stronger Ψ-ratios (Fig. 2E). As levels of pseudouridylation were not used in the training of the model, this result strongly argues for its biological relevance, i.e., that the features captured by the model are also “perceived” by TRUB1.

The near-perfect separation between the positive and negative set of sites achieved by the model (Fig. 2F) argues that pseudouridylation by TRUB1 is determined almost exclusively at the cis level and that the combination of sequence and structural elements identified here are both necessary and sufficient for acquisition of pseudouridylation. Nonetheless, the model assigned low probabilities of pseudouridylation to a number of sites that are pseudouridylated to high levels (Fig. 2F). Examination of these exceptions found them to be in a context predicted to fold into variations of the consensus stem–loop structure. In one case, the 7-bp loop was extended to 8 bp (Fig. 2G) and in another reduced to 6 bp (Fig. 2H) and hence not accurately predicted by the model. We found other cases in which base-pairing at some of the positions in the stem was abolished but compensated by an overall longer stem (Fig. 2I–L). In many of the cases, we further observed a potential for G-U base-pairing in the stem, often also compensated by a longer stem (Fig. 2H–L). Thus, these exceptions reinforce the requirement for both the stem and the loop for achieving pseudouridylation and suggest various layers of flexibility in their formation.

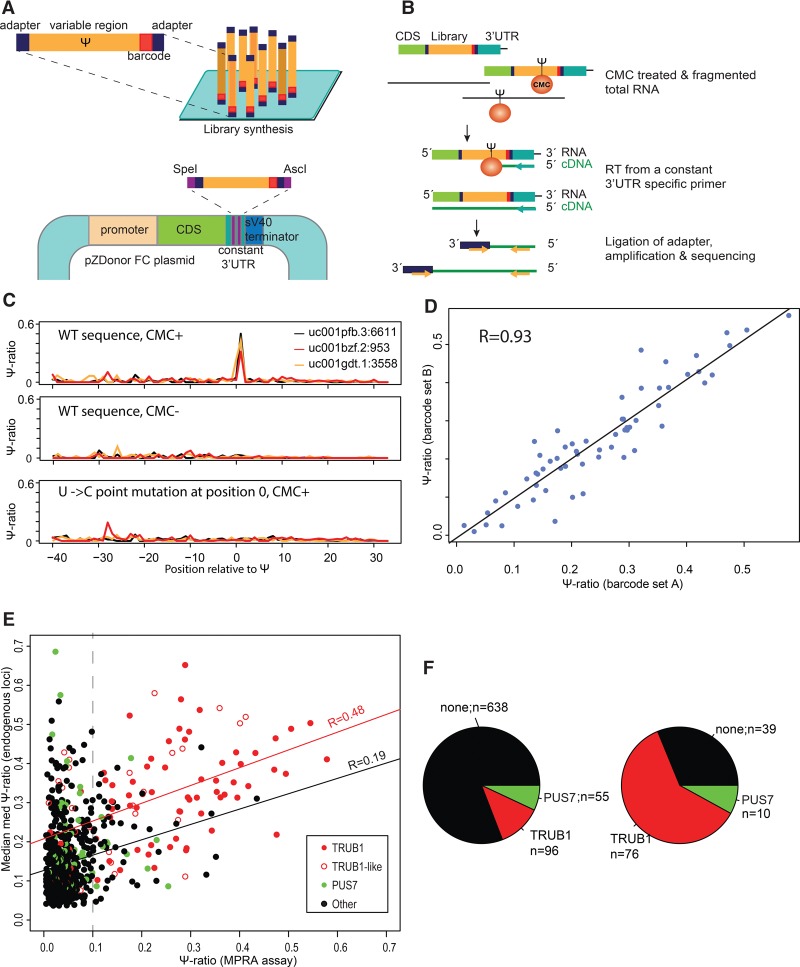

Validation of pseudouridylation maps using massively parallel reporter assays

To comprehensively validate the putative pseudouridylated position and to allow direct assessment of the factors contributing to their specificity, we employed massively parallel reporter assays. Specifically, we designed 6411 sequence variants comprising 65 nt surrounding a putative pseudouridylated site, along with a large set of carefully designed counterparts, designed to systematically impact the sequence and secondary structure surrounding the putative sites. Each of these sequences further comprised a unique 8-nt barcode and common adapters on both ends (Supplemental Table S2). These pooled sequences were cloned as 3′ UTR elements downstream from an arbitrarily selected gene (Fig. 3A). To ensure obtaining adequate sequence coverage for each of the sequence variants, we developed a targeted version of Ψ-seq, relying on construct-specific priming of reverse-transcription (Methods) that provided readouts of Ψ levels exclusively within the constructs (Fig. 3B). Using this strategy, relatively shallow sequencing depth (∼2–20M reads) yielded deep coverage for the vast majority of constructs, with 98.5% of the constructs covered by >200 reads.

Figure 3.

Establishment of massively parallel reporter assay and validation of selected targets. (A) Thousands of sequence variants surrounding pseudouridylated sites or mutated counterparts, each harboring a unique 8-nt barcode and flanked by an adapter set, are cloned downstream from a reporter gene and transfected into cells. (B) Strategy employed for obtaining targeted readouts of pseudouridine within the constructs. Following CMC-treatment, total RNA was reverse-transcribed using a construct-specific primer. A DNA adapter was subsequently ligated to the cDNA, and DNA was amplified using one primer harboring complementarity to the adapter sequence and a second one downstream from the sequence employed for reverse-transcription (Methods). (C) Ψ-ratios across a 70-nt window surrounding three endogenously pseudouridylated sites at TRUB1 targets, within the indicated genes. In all three cases, the pseudouridylation is precisely recapitulated at the correct site in the WT, CMC-treated sample (upper panel) but completely eliminated in the absence of CMC treatment (middle panel), or upon point-mutation of the pseudouridylated site (lower panel). (D) Scatterplot presenting the correlation between Ψ-ratios measured for identical sequences (the set of 74 WT TRUB1 sites), differing only in their 8-nt barcode. (E) Correlation between Ψ-ratios, as captured in the massively parallel reporter assay, and the median med-Ψ- ratios measured across the three large data sets analyzed in this study. TRUB1 sites are defined as harboring a GTTCNANNC consensus, and TRUB1-like sites are defined as GTT[A/G/T]NANNC. The regression curve is plotted in red for all TRUB1 and TRUB1-like sites, in black for all remaining sites. (F) Pie chart depicting the distribution of TRUB1, PUS7, and other consensus sequences throughout the 789 validated sites (left panel) and among all sites with Ψ-ratios > 0.1 (right panel).

Confirming the validity of this approach, we found that pseudouridylation within the constructs occurs precisely at the endogenous position but is completely abolished using sequence variants in which the pseudouridylated position is point-mutated to a “C” (Fig. 3C). Moreover, no evidence for termination of reverse-transcription at the pseudouridylated site is present in the untreated (CMC-) samples, which were otherwise subjected to an identical protocol (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the quantification of Ψ levels in this assay was highly reproducible (R = 0.93, P < 2.2 × 10−16) and not impacted by the sequence-specific barcodes, as measured using identical sets of sequences differing only in their barcode (Fig. 3D).

We then analyzed a set of 789 sites, comprising all “T” harboring sites in the “high” and “highest” confidence groups (i.e., reproducibly detected in at least two of the three studies), excluding sites within noncoding genes (tRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs). In 125 of 789 sites, we were able to recapitulate termination of reverse-transcription in the constructs at relatively high rates (Ψ-ratio >0.1) (Fig. 3E). Strikingly, the set of sites in which we could recapitulate RT termination was strongly enriched for sequences containing TRUB1 and PUS7 consensus sequences—these targets were present at 86 of the validated targets (69%), compared to 19% across the entire data set chosen for validation (Fig. 3F). Moreover, levels of Ψ at TRUB1 targets were relatively well-correlated with the measurements at the endogenous targets (R = 0.48, P = 6.2 × 10−7) (Fig. 3E); This correlation was substantially poorer for non-TRUB1-containing sequences (R = 0.19, P = 5.4 × 10−7). Collectively, this experiment strongly suggests that the RNA sequence is sufficient to direct specific levels of pseudouridylation at TRUB1 targets, and to a lesser extent at targets of PUS7. The fact that Ψ at other putative targets was typically only recapitulated to low levels, or not at all, in the reporter assays may either imply that the regulation on the PUSs catalyzing Ψ at these sites is more complex or the presence of false positives among these sites.

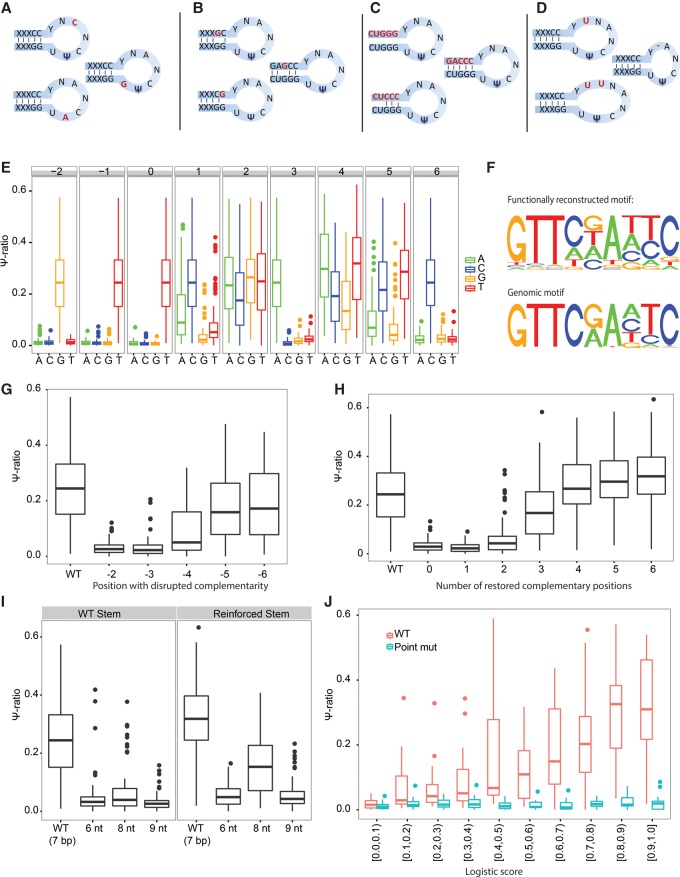

Validating TRUB1 specificity using massively parallel reporter assays

We next sought to systematically test the extent to which the various elements identified in our computational model are required for achieving pseudouridylation. To this end, we first assembled a data set of 74 TRUB1 targets, harboring all sites within mRNAs comprising a GTTCNANNC motif identified in the Schwartz et al. data set. On the basis of these targets we next systematically point-mutated elements in the loop (Fig. 4A), perturbed and restored complementarity in the stem region (Fig. 4B,C), and characterized the constraints on loop length (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Validation of TRUB1 consensus motif using MPRA analysis. (A–D) Scheme of systematic mutations employed in this study, perturbing the sequence of the loop (A), individual positions in the stem structure (B), all positions in the stem structure along with compensatory mutations systematically restoring complementarity (C), and the size of the loop (D). (E) Seventy-four sites containing a TRUB1 consensus motif were systematically point-mutated at each position. Boxplots capturing the distribution of Ψ-ratios across each of the 74 sites are depicted in each of the perturbations. (F) (Top panel) For each of the indicated positions, we first extracted the median Ψ-ratio obtained using each of the 4 nt. The median Ψ-ratio for each of these nucleotides was then divided by the sum of the Ψ-ratios across all 4 nt, to yield relative Ψ-ratios (summing up to 1, at each position). The height of each nucleotide at each position was then plotted in direct proportion to its relative Ψ-ratio. (Bottom panel) The sequence motif of TRUB1, as identified in Figure 1D, is plotted to ease the comparison with the functionally defined motif. (G) Distribution of Ψ-ratios, following disruption of the base-pairing ability of each of the indicated positions in the stem structure. The distribution for WT sequences is presented in comparison. (H) Distribution of Ψ-ratios following elimination and gradual sequential restoration of the stem structure, beginning with zero complementary bases up to six complementary bases. (I) Distribution of Ψ-ratios following extension (to 8 or 9 nt) or shrinking (to 6 nt) of loop length, either based on the WT TRUB1 sites (left), or based on variants with particularly strong stems (right) of six consecutive base pairs. (J) Distribution of Ψ-ratios across 250 sites with varying logistic scores of TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation. Twenty-five sites were selected for each of 10 logistic score bins, ranging from 0 to 1. As controls, distributions of Ψ-ratios are shown also for 250 counterparts in which we designed a T→C point-mutation at the pseudouridylated site.

We began by measuring the extent to which each individual nucleotide in the loop region and at the first stem position is required for pseudouridylation by systematically point-mutating each nucleotide at each of these positions into every other nucleotide (Fig. 4A). Using this analysis, we were able to reconstruct de novo the precise TRUB1 consensus sequence (Fig. 4E). This analysis further highlighted sequence flexibility and constraints not apparent in the consensus sequence, including a flexibility at position +1, in contrast to the originally defined consensus sequence in which it is invariably a “C,” and a strong preference for A and T at position +4 (Fig. 4E). Indeed, pseudouridylation is apparent at sites containing nucleotides other than “C” at position +1, as is apparent among the validated set of sites in the “high” and “highest” confidence bins (TRUB1-like motifs ) (Fig. 3E).

We then systematically assayed the consequences of perturbing the stem structure by abolishing the ability of each of positions −2 to −6 to base-pair with their opposite sequences (+6 to +10, respectively). Our results clearly indicate that the requirement for base-pairing decreases as a function of distance from the loop, with base-pairing of positions −2 and −3 being critical for pseudouridylation and more distant positions being of decreasing importance (Fig. 4G).

As a complementary experiment, we next completely abolished the ability of positions −2 to −6 to base-pair with their opposite sequences. This completely abolished pseudouridylation (Fig. 4H). We then systematically restored base-pairing between an increasing number of consecutive positions, beginning at position −2. Pseudouridylation levels increased as a function of base-pairing positions: While base-pairing only of position −2 was insufficient to achieve pseudouridylation, base-pairing of −2 and −3 was sufficient to achieve low levels of pseudouridylation, and these increased continuously, achieving maximal levels when all of positions −2 to −7 could form base pairs with positions +6 to +11. Of note, levels obtained at maximal complementarity of the stem were even higher than the ones observed in the WT sequences, in which the extent of complementarity is typically reduced.

To assess the impact of loop length, we next either decreased the size of the loop to 6 nt or increased it to 8 or to 9 nt. Pseudouridine levels were severely impacted by these perturbations, albeit remaining higher than upon T→C point-mutation of the pseudouridylated position (Fig. 4I). To assess whether a stronger stem can compensate for an increased/decreased loop, we assessed the impact of altering loop length in the set of constructs described above in which positions −2 to −7 are fully complementary to positions +6 to 11 and which are pseudouridylated to higher levels than WT. Indeed, this analysis revealed that pseudouridylation is achieved within such constructs when the loop is expanded to 8 nt, but that only very low levels are obtained when the loop is expanded to 9 bp or reduced to 6 (Fig. 4I). Thus, these results demonstrate that a more stable stem can compensate for a nonoptimal loop. More broadly, these systematic mutations comprehensively characterize the sequence and structural requirements required for pseudouridylation via TRUB1.

Genome-wide prediction and validation of TRUB1-dependent Ψ sites

While experimental detection of all TRUB1 sites using Ψ-seq is challenging because within any given cell type only a fraction of the genes harboring a TRUB1 consensus site are expressed and ultradeep coverage is required for reliable detection, our computational model provided an opportunity to predict TRUB1 substrates at a genome-wide level. We applied our computational model to all 14,381 sites in human harboring a TRUB1 consensus motif, and assigned each site a logistic score, predicting its susceptibility to TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation (Supplemental Table S3).

To validate the predictions by the model, we selected 250 sites, with predicted logistic scores uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 and that had not been identified as pseudouridylated in the Schwartz et al. data set. We then used MPRA to measure pseudouridylation levels at each of these sites upon introduction into a synthetic sequence environment. We obtained a strong correspondence between the predicted pseudouridylation scores and the tested levels (R = 0.62, P < 2.2 × 10−16) (Fig. 4J), strongly supporting the predictions made by the model.

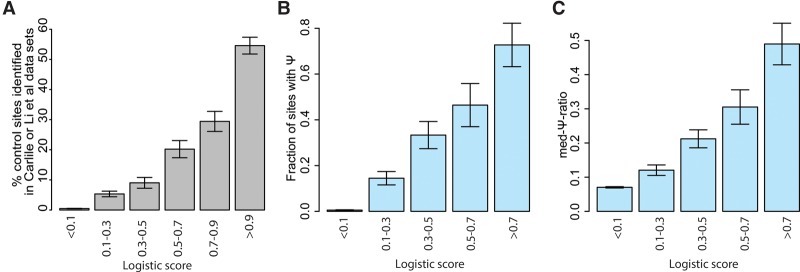

To further validate the predictions by the model in an endogenous context, we next assessed whether we could find evidence for pseudouridylation at sites predicted by the model (which had been trained exclusively on the Schwartz et al. data set) in the Carlile et al. and Li et al. data sets. A site was considered as validated it if had been identified as a putative Ψ site in either of these two data sets. Importantly, the model had been trained exclusively based on Ψ data in HEK293 cells in the Schwartz et al. data set, and for this analysis we eliminated all sites that had formed part of the test group in training the above model. We observed a striking overlap between the model's prediction and pseudouridylation state in these two data sets (Fig. 5A). Fifty-five percent (173/317) of the sites predicted to be TRUB1 substrates (logistic score > 0.9) had been identified as pseudouridylated in at least one of the two data sets. Conversely, of 12,750 predicted nontargets (logistic score < 0.1), only 62 (0.5%) had been identified as potentially pseudouridylated in either of the two data sets.

Figure 5.

Validation of model predicting TRUB1 sites. (A) Percentage of control sites identified as being putatively pseudouridylated in either the Carlile et al. or Li et al. data sets, calculated across six bins of the logistic regression-based score. (B) Correlation of the logistic score with sites identified in mouse. Fraction of sites with experimentally measured pseudouridine are depicted across five bins of increasing logistic scores. (C) Ψ levels (captured by med-Ψ-ratios) in mouse, shown across the five bins in B.

TRUB1-dependent pseudouridylation of mRNA is conserved in mouse tissues

To assess the extent to which features of TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation are conserved between human and mouse, we applied the computational model to the mouse transcriptome and generated predictions for 14,763 nonredundant sites containing the TRUB1 consensus to which we applied the above logistic model. We then obtained measurements for Ψ-mapping in brain and in liver (Li et al. 2015), which were analyzed using the above-described pipeline. As in human, the top motif identified de novo, using the above-described unbiased motif detection scheme, was the TRUB1 motif, followed by a PUS7 -motif, although pseudouridylation at the latter was more abundant (Supplemental Fig. S2A,B; see also the Discussion). Correlating the Ψ predictions against the Ψ measurements for 3688 sites for which sufficient read depth was available, we found that the human-derived computational model predicting Ψ state was able to capture both whether and the extent to which sites harboring a mouse TRUB1 consensus signal were pseudouridylated (Fig. 5B,C). These findings further establish the computational model, confirm that predictable TRUB1-dependent pseudouridylation of mRNA is not restricted to cell lines, and establish TRUB1-dependent mRNA pseudouridylation as evolutionarily conserved between human and mouse.

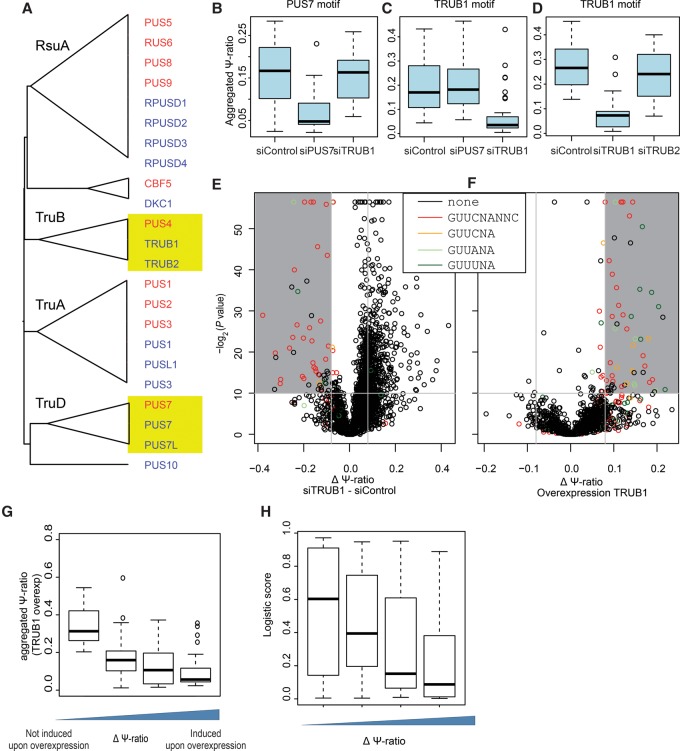

TRUB1 and PUS7 catalyze formation of Ψ on human mRNAs

In human, there are 13 enzymes harboring a PUS domain, which cluster—along with the yeast PUSs—into six families, consistent with previous classifications (Fig. 6A; Gustafsson et al. 1996; Koonin 1996). Yeast Pus4 and Pus7 both have two paralogs in human: TRUB1 and TRUB2 are homologous to yeast Pus4, and PUS7 and PUS7L are homologous to yeast Pus7 (Fig. 6A). To identify which of these enzymes catalyzes Ψ at the sites harboring the Pus4-like and Pus7-like consensus sequences, we knocked down PUS7, TRUB1, and TRUB2 in HEK293 cells using siRNAs and obtained global measurements of Ψ levels using Ψ-seq; PUS7L was expressed at negligible levels in HEK293 cells and hence omitted from this analysis. In all cases, we achieved >80% knockdown (Supplemental Fig. S3A–D). We found that Ψ at sites harboring the PUS7 consensus sequence was significantly reduced with respect to WT following knockdown of human PUS7 (Paired t-test, P = 1 × 10−3) (Fig. 6B). Conversely, performing a similar analysis on sites harboring the TRUB1 consensus sequences, we found that Ψ was dramatically reduced at these sites following knockdown of TRUB1 (P = 4.8 × 10−15) (Fig. 6C) but not of TRUB2 (P = 0.07) (Fig. 6D). Putative sites lacking these motifs did not show any decrease following knockdown of these factors (Supplemental Fig. S3E). These results were further confirmed in an unbiased analysis (not limiting the analysis a priori to sites harboring specific sequence motifs) which revealed that the overwhelming majority of sites with a considerable and statistical drop in Ψ levels following TRUB1 knockdown harbored a TRUB1 consensus sequence (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Genetic perturbations reveal proteins catalyzing Ψ at PUS7 and TRUB1 mRNA targets. (A) Phylogenetic tree of all human and yeast proteins comprising a PUS domain. Multiple alignments and trees were generated using MAFFT. Nodes were collapsed to highlight the classification of PUS domain families in bacteria, which are indicated when available. (B) Distribution of Ψ-ratios for sites containing a PUS7-like motif (n = 13) measured following knockdown of PUS7, TRUB1, or mock knockdown in HEK293 cells. Experiments were performed at least in replicates; putative peaks were identified based on the full data set (Methods), following which an aggregated Ψ-ratio was calculated for each site, defined as the number of reads from all replicates terminating at the site, divided by all reads overlapping it. (C) Analysis as in B but for sites harboring a TRUB1 consensus motif (n = 49). Panels B and C are based on the same experimental data set. (D) Distribution of Ψ-ratios for sites containing a TRUB1 motif (n = 14) following knockdown of either TRUB1 or TRUB2, or mock knockdown. (E) Volcano plot depicting the difference in Ψ-ratio between TRUB1 knockdown and mock knockdown cells (x-axis) and the associated t-test-derived P-value based on triplicates in each condition (y-axis) for each of the putative Ψ positions. Sites harboring a TRUB1 consensus sequence, or derivatives thereof, are colored as indicated. (F) Volcano plot, as in E. Differences in Ψ-ratios following overexpression of TRUB1 and Ψ-ratios following TRUB2 overexpression (used as a proxy for a negative control) are plotted. (G) Distribution of aggregated Ψ-ratios measured in the TRUB1 overexpression samples, plotted as a function of the difference in Ψ-ratios in samples overexpressing TRUB1 versus TRUB2. (H) Distributions of logistic regression-based pseudouridylation scores across sites that are induced following overexpression, divided into four bins as in Figure 2E.

To further test the requirement of TRUB1 for catalyzing Ψ at TRUB1 consensus sequences, we overexpressed TRUB1 and TRUB2 in HEK293 cells (Supplemental Fig. S3F–H). The overwhelming majority of sites with a significant increase in Ψ levels following overexpression of TRUB1, but not of TRUB2, contained the TRUB1 consensus sequences or derivatives thereof (Fig. 6F), strongly confirming the involvement of TRUB1, and not of TRUB2, in their catalysis.

Interestingly, we noted that distinct TRUB1 targets responded in different ways to overexpression of TRUB1. For instance, at ∼30% of TRUB1 consensus sequence (GUUCNANNC), Ψ-ratios increased by >10% following overexpression, whereas in ∼14% there was no change or even a decrease in TRUB1 levels. The inducibility of sites correlated inversely with the Ψ-ratio at these sites, such that the most inducible sites were ones that—in the absence of overexpression—were pseudouridylated to the lowest levels, suggesting that they are poorer substrates of TRUB1 (Fig. 6G). Consistently, the sites that acquired Ψ upon overexpression have a significantly lower Ψ logistic score than their uninducible counterparts (Fig. 6H). Thus, the nonoptimal sequence and structure composition of these sites likely leads to lower affinity of binding of TRUB1, resulting in lower levels (or lack) of pseudouridylation at these sites under WT conditions and can be compensated for by increased expression of TRUB1.

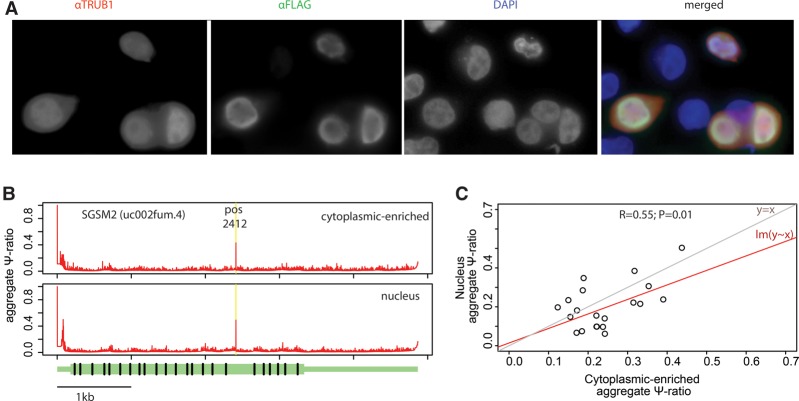

TRUB1-dependent mRNA pseudouridylation occurs in the nucleus

Finally, we sought to assess within which subcellular compartment Ψ at TRUB1 target sites is catalyzed, given that PUSs can shuttle between different cellular compartments (Becker et al. 1997; Lecointe et al. 1998; Schwartz et al. 2014). Immunofluorescent staining against FLAG-tagged TRUB1 revealed it to be present in both the nuclear and cytosolic fractions (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Fig. S4A). These findings were confirmed via Western blotting of cytosolic-enriched and nuclear fractions of TRUB1 (Supplemental Fig. S4B) and are further supported by published mass-spectrometry data sets of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, based on which TRUB1 is present in both (Boisvert et al. 2012). To assess whether TRUB1 is already active in the nucleus, we purified nuclear and cytoplasmic-enriched subcellular fractions and performed Ψ-seq on these fractions in triplicate. Purity of the nuclear fraction was confirmed by Western blot (Supplemental Fig. S4C), as well as by the strong enrichment for intronic RNAs and for nuclear RNAs (Supplemental Fig. S4D,E). Analysis of sites harboring TRUB1 motifs in these fractions revealed that pseudouridylation was already observed, in the majority of cases, in the nucleus (Fig. 7B,C). We observed a strong overall correlation between Ψ levels in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7C). Nonetheless, Ψ levels were generally reduced in the nuclear fraction (P = 0.02) (Fig. 7C), likely reflecting the fact that the nuclear fraction also contains nascent and very partially processed RNAs that have not yet acquired the modification, whereas the cytoplasmic fraction is strongly enriched for fully processed transcripts. Thus, while we cannot exclude that some TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation does occur in the cytoplasm, our results suggest that such pseudouridylation is predominantly nuclear.

Figure 7.

TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation occurs in the nucleus. (A) HEK293T cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged TRUB1 were stained with αTRUB1 (red), αFLAG (green), and DAPI (blue). Representative image (600×) is shown, with overexpressed TRUB1 found in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of transfected cells. (B) Depiction of aggregate Ψ-ratios across the SGSM2 gene in the cytoplasmic-enriched (top) or nuclear (bottom) fractions; values at pseudouridylated position 2412 are highlighted in yellow. (C) Scatterplot depicting aggregate Ψ-ratios across the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions for 20 sites that passed the thresholds of detection in our pipeline, harbored a “GUUC” core motif, and with ≥15 reads overlapping the site in the treated fraction. The regression line (lm[y ∼ x]) and the y = x lines are depicted.

Discussion

Characterization of PUSs acting on human mRNA

Characterization of the landscape of Ψ on human mRNA and the factors underlying their biogenesis is a crucial stepping stone toward dissecting the regulatory role of this previously unrecognized layer of transcriptional complexity. Focusing on a conservatively defined high-confidence set of sites reproducibly detected across three large data sets and aided by genetic perturbations, we found that a single PUS, TRUB1, catalyzes the formation of the majority of detected sites and that its mRNA substrates are also the ones pseudouridylated to the highest levels. TRUB1 homologs are conserved from bacteria to human and have traditionally been studied almost exclusively in the context of their role in modifying a highly conserved site in position 55 of tRNA (Nurse et al. 1995; Gu et al. 1998; Hoang and Ferré-D'Amaré 2001; Zucchini et al. 2003). Recently, we and others have found some yeast mRNA substrates to be modified by Pus4 (Carlile et al. 2014; Lovejoy et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014), and this activity on mammalian mRNA is thus conserved from yeast to human. An open question pertains to the role of TRUB2. Despite its sequence homology to TRUB1 and its higher levels of expression, it does not compensate for depletion of TRUB1 nor does its overexpression lead to Ψ at TRUB1 targets. Thus, the targets of TRUB2 remain to be determined.

An additional PUS which we find to direct pseudouridylation of mammalian mRNA is PUS7. Across all analyzed data sets, levels of Ψ achieved at PUS7 targets were decreased compared to TRUB1 targets, and the size of the PUS7 repertoire among high-confidence target sites was much reduced compared to TRUB1. However, this must be interpreted with caution, as in the unbiased motif search in both the Carlile et al. data set (Supplemental Fig. S1E) and in the mouse data set (Supplemental Fig. S2), PUS7 motifs were the most frequent. The relative paucity in PUS7 targets at the intersection of the three analyzed data sets here may therefore reflect cell-type–specific activity of PUS7, leading to its detection in only some cell types or conditions but not in others. This would be in line with our observations of dynamic PUS7-mediated pseudouridylation of mRNA in yeast, which occurs at only a low number of sites under standard growth conditions but is induced at hundreds of sites in heat shock (Schwartz et al. 2014).

While TRUB1 and PUS7 together account for ∼60% of reproducibly detected sites across all three data sets, the remaining ∼40% remain unaccounted for, in addition to thousands of putative sites identified across only a subset of the data sets, which for the most part are not attributable to either of these enzymes. It is thus likely that at least a subset of these sites reflects accumulation of Ψ via additional PUSs acting either in a site-specific manner and/or guided by H/ACA box snoRNAs.

Specificity of site-recognition by TRUB1

Our characterization of TRUB1 targets demonstrates the requirement for a well-defined stem and loop structure for achieving pseudouridylation, well in line with in vitro experiments characterizing TRUB1 binding to a 17-nt synthetic sequence capturing the Ψ site on position 55 of tRNA (Gu et al. 1998). The near-perfect performance of a computational model in discriminating TRUB1 targets from nontargets, coupled with our analyses based on the massively parallel reporter assays, demonstrate that these features are both necessary and sufficient for achieving mRNA pseudouridylation.

Given these observations, it is likely that TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation of mRNA is, at least to some extent, a “constitutive” feature of mRNA, hard-coded into the RNA sequence, and one which is not controlled locally. Nonetheless, by modulating levels of TRUB1 (or its subcellular localization), cells can retain a potential for dynamic global control over TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation. Increased levels of TRUB1 under specific conditions/tissues/disease states are expected to lead to global increases both in the number of pseudouridylated targets and in Ψ levels at low-affinity sites, whereas decrease in TRUB1 levels is expected to lead to the opposite scenario.

Thus, TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation is the first example for an mRNA modification whose specificity is close to being completely understood and hence predictable. In contrast, far less is understood about the specificity of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) (Dominissini et al. 2012; Meyer et al. 2012; Schwartz et al. 2013), N5-methylcytosine (m5C) (Squires et al. 2012), or N1-methyladenosine (m1A) (Dominissini et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016) on mRNA, which have all been mapped globally and yet whose consensus sequences are far more degenerate. Elucidating the factors governing the specificity of these modifications is of crucial importance to unravel the regulatory constraints to which they are subjected, and the approach utilized by this study of dissecting the modification specificity using massively parallel reporter assays may be generalizable to these modifications as well.

Function of TRUB1-mediated pseuoduridylation of mRNA

A critical question remaining to be addressed is the functional role of TRUB1-mediated pseudouridylation in mRNA. In the context of tRNA and rRNA, studies have mostly focused on the impact of Ψ on RNA structure, where it is thought to contribute to structural stability through the potential formation of an extra hydrogen bond (Durant and Davis 1997, 1999; Kierzek et al. 2014). Such a structural role, if present on mRNA, could modulate the ability of RNA binding proteins to bind to the mRNA, perhaps in an analogous manner to the role recently reported for N6-methyladenosine (Liu et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2015) and, in this manner, impact its localization, stability, or translation. In yeast, we previously observed that steady state levels of mRNAs pseudouridylated via Pus7 were ∼25% decreased following knockout of PUS7, suggestive of a potential role for pseudouridine in stabilizing messages (Schwartz et al. 2014). We do not observe such an effect for sites pseudouridylated via TRUB1 following TRUB1 knockdown (data not shown). Pseudouridine of mRNA may potentially lead to recoding of the encoded amino acid, a hypothesis that is supported by findings of robust read-through observed beyond the stop codon when a stop codon is synthetically pseudouridylated (Karijolich and Yu 2011). Thus, the functions of TRUB1-dependent pseudouridylation of mRNA remain to be determined.

Challenges in transcriptome-wide detection and quantification of Ψ

Even with the advent of the recent methodologies for detecting and quantifying Ψ, substantial challenges remain to be overcome to allow accurate and quantitative Ψ mappings at a truly transcriptome-wide level. While Ψ maps on rRNA are typically highly precise, obtaining rRNA-like depth is unrealistic for much more lowly expressed mRNAs, and hence the thresholds used for detection of Ψ sites are ones that can result not only in a large number of false negatives but also of false positives. Similarly, the ability to quantify the levels of Ψ is dramatically impacted by the relatively low read numbers that are acquired for most sites and lead to substantial variability in the estimates of Ψ levels. Here, we demonstrate that through overlaying a large number of data sets with orthogonal levels of evidence, including sequence motifs, genetic perturbations, and massively parallel reporter assays, high-quality collections of experimentally measured sites can be obtained. This strategy can be extended to additional post-transcriptional modifications of mRNA to both provide accurate maps and allow defining the elements underlying substrate specificity.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the role of Ψ on mRNA is in its infancy. Our findings here substantially advance our understanding regarding the Ψ landscape in human and the key factors catalyzing and regulating its formation. The resource of a validated high-confidence and ranked collection of Ψ sites is anticipated to allow further functional and mechanistic dissection of this post-transcriptional and disease-implicated modification.

Methods

Read mapping and Ψ detection

Detection of Ψ was performed essentially as described in Schwartz et al. (2014), in the form of a single pipeline that was applied to data sets of Li et al. (2015), Carlile et al. (2014), and Schwartz et al. (2014). A detailed explanation of the three tiers of analysis is presented in the Supplemental Methods.

Detection and clustering of prevalent and highly pseudouridylated sequence motifs

We developed a motif-finding approach that simultaneously takes into consideration both the prevalence of a motif in a data set and the extent to which sites harboring the motif are pseudouridylated. The full details of our approach along with a script implementing it are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Prediction of RNA secondary structure

For predicting secondary structure in the region surrounding TRUB1-dependent pseudouridylation sites, we extracted a sequence window of 24 bp, beginning 10 bp upstream of the pseudouridylation site until 13 bp downstream. Free energy calculations for predicted secondary structures were calculated using RNAfold version 2.1.5, applying a constraint that the constant U, U, C, and A at positions −1, 0,1, and 3, respectively, be unpaired, using the parameter ‘--constraint ……..xxx.x………..’.

Characterization and modeling of TRUB1-dependent pseudouridylation sites

Details pertaining to data set generation, feature selection, and the generated model are presented in Supplemental Methods.

Massively parallel reporter assay

Design

All sequences described within the manuscript were synthesized as a single pool using oligo arrays (Twist Bioscience). Each sequence was designed as a 109-nt-long sequence, comprising an 18-nt-long adapter (ATGGGGTTCGGTATGCGC), a 65-nt-long variable region comprising 32 bases upstream of the pseudouridylated sites and 32 downstream, an 8-nt-long barcode, and a 3′ 18-nt-long adapter (AAGGCTCCCCGAGACGAT). Additional details pertaining to design and cloning of the sequences are presented in Supplemental Methods.

Targeted measurement of pseudouridylation within the construct

A 10-cm plate of HEK293T cells was transiently transfected with 20 µg of the library plasmid using jet-PEI (polyplus transfection). RNA was purified using Nucleozol reagent (Macherey Nagel). Ψ-seq was performed on total RNA essentially as described in Schwartz et al. (2014), without adapter ligation to the RNA, as reverse-transcription was carried out from a constant sequence stemming from the plasmid (AGCATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAAAGG). Adapter ligation to the cDNA was carried out as described, followed by PCR enrichment with an inner plasmid-specific primer (GGTCCGATATCGAATGGCGC), carrying indexed Illumina adapters (primers used for the amplification were: Indexed_ oligo_A1_pZDonor_FC_specific CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCCTGGTAGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTGGTCCGATATCGAATGGCGC 2P_universal AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT).

MPRA data analysis

A custom reference transcriptome was generated, comprising each of the variable 6380 sequences (“chromosomes”) embedded within a 328-bp target environment in the plasmid, into which it was cloned. Paired-end reads from both CMC-treated (CMC+) and nontreated (CMC−, Input) were aligned to the custom reference transcriptome, using the STAR aligner (version 2.1.5b), enforcing a global (rather than local) alignment with a maximum of three mismatches, and without allowing introns, using the parameters “--alignEndsType EndToEnd --outFilterMismatchNmax 3 --alignIntronMax1.” A custom script was subsequently used to calculate the number of reads starting and overlapping each site, based on which Ψ-ratios were calculated for each position.

Prediction of TRUB1 targets in mouse

For the analysis in mouse, we generated a data set of 14,763 nonredundant sites containing the TRUB1 consensus, to which we applied the above logistic model. We identified a set of 3688 sites with a median coverage of >30 reads, overlapping them across the four mouse data sets (two in liver and two in brain) in Li et al., which were used as a basis for the analyses in Figure 5.

Cell culture for knockdown and overexpression experiments

Knockdown and overexpression were performed in HEK293 cells based on standard protocols (Supplemental Methods).

Analysis of differential pseudouridylation

The two knockdown sets of experiments and the overexpression experiment presented in this manuscript were performed and analyzed as separate data sets, using the above-detailed procedure. For the volcano plots (Fig. 6E,F), we then defined a test and control condition, whereby test consisted of all replicates harboring the perturbation of choice (e.g., knockdown/overexpression of TRUB1), and control consisted of all remaining samples in the data set (e.g., siControl, siTRUB2). We then aggregated read counts across the replicates and recalculated Ψ-ratios for test/control based on the aggregated reads. The aggregated counts were used to calculate a χ2 P-value for each putative site, based on a contingency matrix comprising an aggregated count of reads beginning or overlapping the putative site in the test condition and the corresponding values in the control condition. These P-values were plotted on the volcano plot y-axis (Fig. 6E,F), and the difference between the aggregated Ψ ratio between the test and control was plotted on the x-axis.

Immunostaining

HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmid encoding FLAG-tagged TRUB1 using PolyJet reagent (SignaGen Laboratories). Two days after transfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked (3% BSA + 4% FBS), and stained overnight with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-TRUB1 (Sigma) and mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma). Cy2 anti-mouse and Cy3 anti-rabbit (Jackson) were used as secondary antibodies. Nuclear staining was performed using DAPI following a standard protocol.

Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was carried out using a LSM 780 system (Zeiss). Fluorescent microscopy was carried out using an Olympus IX73 system.

Nuclear/cytoplasmic fraction

HEK293T cells were fractionated using the PARIS kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were filtered prior to fractionation to avoid clumps.

Data access

Raw and processed sequencing data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE90851.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the Israel Science Foundation (543165), the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 714023), by the Abisch-Frenkel-Stiftung, by research grants from The Abramson Family Center for Young Scientists, the David and Fela Shapell Family Foundation INCPM Fund for Preclinical Studies, the Estate of David Turner, and the Berlin Family Foundation New Scientist Fund.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.207613.116.

References

- Anantharaman V, Koonin EV, Aravind L. 2002. Comparative genomics and evolution of proteins involved in RNA metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 1427–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakin AV, Ofengand J. 1998. Mapping of pseudouridine residues in RNA to nucleotide resolution. Methods Mol Biol 77: 297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HF, Motorin Y, Planta RJ, Grosjean H. 1997. The yeast gene YNL292w encodes a pseudouridine synthase (Pus4) catalyzing the formation of Ψ55 in both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 4493–4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert F-M, Ahmad Y, Gierliński M, Charrière F, Lamont D, Scott M, Barton G, Lamond AI. 2012. A quantitative spatial proteomics analysis of proteome turnover in human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: M111.011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaya Y, Casas K, Mengesha E, Inbal A, Fischel-Ghodsian N. 2004. Missense mutation in pseudouridine synthase 1 (PUS1) causes mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA). Am J Hum Genet 74: 1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Zinshteyn B, Shin H, Bartoli KM, Gilbert WV. 2014. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515: 143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charette M, Gray MW. 2000. Pseudouridine in RNA: what, where, how, and why. IUBMB Life 49: 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, et al. 2012. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485: 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben-Haim MS, Dai Q, Di Segni A, Salmon-Divon M, Clark WC, et al. 2016. The dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature 530: 441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant PC, Davis DR. 1997. The effect of pseudouridine and pH on the structure and dynamics of the anticodon stem-loop of tRNA(Lys,3). Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 36: 56–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant PC, Davis DR. 1999. Stabilization of the anticodon stem-loop of tRNALys,3 by an A+-C base-pair and by pseudouridine. J Mol Biol 285: 115–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Vizarra E, Berardinelli A, Valente L, Tiranti V, Zeviani M. 2009. Nonsense mutation in pseudouridylate synthase 1 (PUS1) in two brothers affected by myopathy, lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anaemia (MLASA). BMJ Case Rep 2009. 10.1136/bcr.05.2009.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Yu M, Ivanetich KM, Santi DV. 1998. Molecular recognition of tRNA by tRNA pseudouridine 55 synthase. Biochemistry 37: 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C, Reid R, Greene PJ, Santi DV. 1996. Identification of new RNA modifying enzymes by iterative genome search using known modifying enzymes as probes. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 3756–3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, Klauck SM, Wiemann S, Mason PJ, Poustka A, Dokal I. 1998. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nat Genet 19: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang C, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. 2001. Cocrystal structure of a tRNA Ψ55 pseudouridine synthase: nucleotide flipping by an RNA-modifying enzyme. Cell 107: 929–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karijolich J, Yu Y-T. 2011. Converting nonsense codons into sense codons by targeted pseudouridylation. Nature 474: 395–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierzek E, Malgowska M, Lisowiec J, Turner DH, Gdaniec Z, Kierzek R. 2014. The contribution of pseudouridine to stabilities and structure of RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 3492–3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV. 1996. Pseudouridine synthases: four families of enzymes containing a putative uridine-binding motif also conserved in dUTPases and dCTP deaminases. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 2411–2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecointe F, Simos G, Sauer A, Hurt EC, Motorin Y, Grosjean H. 1998. Characterization of yeast protein Deg1 as pseudouridine synthase (Pus3) catalyzing the formation of Ψ38 and Ψ39 in tRNA anticodon loop. J Biol Chem 273: 1316–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhu P, Ma S, Song J, Bai J, Sun F, Yi C. 2015. Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat Chem Biol 11: 592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Xiong X, Wang K, Wang L, Shu X, Ma S, Yi C. 2016. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol 12: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. 2015. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA–protein interactions. Nature 518: 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy AF, Riordan DP, Brown PO. 2014. Transcriptome-wide mapping of pseudouridines: Pseudouridine synthases modify specific mRNAs in S. cerevisiae. PLoS One 9: e110799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka MA, Milanowska K, Osman Oglou O, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Olchowik A, Januszewski W, Kalinowski S, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Rother KM, et al. 2013. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways—2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D262–D267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon M, Contreras A, Ruggero D. 2015. Small RNAs with big implications: new insights into H/ACA snoRNA function and their role in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 6: 173–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason C, Jaffrey S. 2012. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149: 1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse K, Wrzesinski J, Bakin A, Lane BG, Ofengand J. 1995. Purification, cloning, and properties of the tRNA Ψ55 synthase from Escherichia coli. RNA 1: 102–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Agarwala SD, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Mertins P, Shishkin A, Tabach Y, Mikkelsen TS, Satija R, Ruvkun G, et al. 2013. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell 155: 1409–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Bernstein DA, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Herbst RH, León-Ricardo BX, Engreitz JM, Guttman M, Satija R, Lander ES, et al. 2014. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159: 148–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen R, Han L, Faqeih E, Ewida N, Alobeid E, Phizicky EM, Alkuraya FS. 2016. A homozygous truncating mutation in PUS3 expands the role of tRNA modification in normal cognition. Hum Genet 135: 707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spenkuch F, Motorin Y, Helm M. 2014. Pseudouridine: still mysterious, but never a fake (uridine)! RNA Biol 11: 1540–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires J, Patel H, Nousch M, Sibbritt T, Humphreys D, Parker B, Suter C, Preiss T. 2012. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 5023–5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Liu N, Diatchenko L, Sachleben JR, Pan T. 2015. N6-methyladenosine modification in a long non-coding RNA hairpin predisposes its conformation to protein binding. J Mol Biol 428: 822–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchini C, Strippoli P, Biolchi A, Solmi R, Lenzi L, D'Addabbo P, Carinci P, Valvassori L. 2003. The human TruB family of pseudouridine synthase genes, including the Dyskeratosis Congenita 1 gene and the novel member TRUB1. Int J Mol Med 11: 697–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.