Abstract

AIM

To compare features of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Hispanics to those of African Americans and Whites.

METHODS

Patients treated for HCC at an urban tertiary medical center from 2005 to 2011 were identified from a tumor registry. Data were collected retrospectively, including demographics, comorbidities, liver disease characteristics, tumor parameters, treatment, and survival (OS) outcomes. OS analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS

One hundred and ninety-five patients with HCC were identified: 80.5% were male, and 22% were age 65 or older. Mean age at HCC diagnosis was 59.7 ± 9.8 years. Sixty-one point five percent of patients had Medicare or Medicaid; 4.1% were uninsured. Compared to African American (31.2%) and White (46.2%) patients, Hispanic patients (22.6%) were more likely to have diabetes (P = 0.0019), hyperlipidemia (P = 0.0001), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (P = 0.0021), end stage renal disease (P = 0.0057), and less likely to have hepatitis C virus (P < 0.0001) or a smoking history (P < 0.0001). Compared to African Americans, Hispanics were more likely to meet criteria for metabolic syndrome (P = 0.0491), had higher median MELD scores (P = 0.0159), ascites (P = 0.008), and encephalopathy (P = 0.0087). Hispanic patients with HCC had shorter OS than the other racial groups (P = 0.020), despite similarities in HCC parameters and treatment.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Hispanic patients with HCC have higher incidence of modifiable metabolic risk factors including NASH, and shorter OS than African American and White patients.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Epidemiology, Treatment pattern, Survival, Hispanics

Core tip: This is a retrospective study evaluating features of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Hispanics compared to those of African Americans and Whites. This large single institution study found that Hispanic patients with HCC presented with more modifiable risk factors, more advanced liver disease, and shorter survival compared to African American and White patients with HCC. Early identification and intervention upon modifiable risk factors may ameliorate HCC development and HCC morbidity in Hispanic patients.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer related mortality[1,2]. While the highest prevalence rates of HCC are in Asia and Africa accounting for 85% of cases in 2008, the incidence of HCC has increased steadily in the United States among most racial and ethnic groups with a greater rate of growth observed in non-White populations[3,4]. Recent SEER analyses reported higher incidence rates for Hispanics (2.5 times) compared to non-Hispanics, and Asian-Pacific Islanders (4 times) and African Americans (1.7 times) compared to Whites[3].

HCC in Hispanics Americans will continue to increase as Hispanics are the most rapidly growing immigrant population in the United States, and projected to comprise 30% of the total population in 2050[5]. Recent studies report differences in HCC presentation in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics, including younger age at diagnosis and greater prevalence of metabolic risk factors for Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic Whites[6,7], and higher incidence of HCC in Hispanic women compared to Hispanic men[6]. Notably, the incidence of liver cancer in Hispanic men has doubled between 1992 and 2012, and is double that of non-Hispanic men[8]. While national HCC incidence is highest in Asians[3,6], Hispanic patients continue to have poorer 5 year survival in comparison to their White and Asian counterparts (respectively; 15% vs 18% vs 23%), and higher overall mortality rates[9,10]. Age adjusted HCC-related mortality rates were reported as more than double in native Hispanic men vs immigrant Hispanic men, suggesting that synergy between biologic, environmental, and acquired risk factors contributes to HCC development in Hispanics in the United States[6]. Despite disproportionately higher incidence and mortality rates of HCC in Hispanics, there is a paucity of information about HCC presentation and features in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics.

Identifying the role of modifiable risk factors associated with HCC in Hispanics will be critical to begin to address racial disparities in HCC incidence rates and outcomes. The aim of the current study was to evaluate HCC risk factors with specific emphasis on modifiable risk factors, disease characteristics, and treatment outcomes in Hispanic patients seen in an academic tertiary medical center in Chicago, Illinois and to compare HCC presentation and outcomes in Hispanics to African American and White patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient populations

All adult patients ≥ 18 years of age with HCC treated at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) from January 2005 to December 2011 were identified from the UIC tumor registry. HCC diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology or according to the American Association of the Study of Liver Diseases non-invasive diagnostic criteria[11]. Hispanic, African American, and White patients were included in the study population; other racial groups were excluded. Patient charts were reviewed for relevant demographic data including comorbidities, liver disease etiology and characteristics, tumor parameters, treatment patterns, and length of survival from presentation. The protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UIC as an expedited review under expedited category 5 (Protocol 2005-0283), and was granted a waiver of informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Variable selection

The primary category of interest was patient identified race/ethnicity. The primary outcome of interest was patient survival. Demographic factors included race, age at diagnosis, gender, insurance status, body mass index (BMI), and metabolic syndrome criteria per the adult treatment panel III guidelines[12]. Comorbidities included diabetes, hyperlipidemia, end stage renal disease requiring dialysis (ESRD), and history of smoking and alcohol use. Assessment of smoking and alcohol consumption was based on patient self-reporting per chart review. Cirrhosis was confirmed by liver biopsy or via characteristic clinical and radiologic features. Liver disease etiology was characterized as hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and other non-viral, non-NASH etiologies including autoimmune, hemochromatosis, and cryptogenic (other). Liver disease characteristics included MELD score calculated based on baseline laboratory values rather than tumor exception points, baseline AFP level, presence of hepatic encephalopathy, and presence of ascites.

Tumor parameters were categorized by size of the largest tumor, stage at diagnosis, portal vein involvement, tumor grade (when tissue was available), and whether HCC was within Milan criteria. Stage at diagnosis was defined as unifocal, multifocal, or metastatic. Assessment was performed regarding whether patients were diagnosed during active HCC surveillance.

Type of treatment was recorded including loco regional therapy, resection, transplantation, chemotherapy, or observation. Cause of death was categorized as attributable to HCC (evidence of radiographic progression in the last 3 mo of life), decompensated cirrhosis (evidence of liver failure or complications of portal hypertension), other, or unknown based on review of outpatient notes within 1 mo of death, discharge summary, and hospice documentation. Two physicians independently reviewed cause of death categorization to ensure criteria standardization.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were first summarized using mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables, median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables. Analysis of variance was used to examine mean differences by race for continuous variables with regards to demographics, comorbidities, liver disease etiology and characteristics, tumor parameters, and treatment patterns. Two-sided χ2 tests or Fishers’ exact test (≤ 5 patients) were conducted to assess specific pairwise differences by race (between Hispanics, African Americans, and Whites) for variables that showed significant overall differences by race (P < 0.05). Further analysis was not performed for groups including ≤ 5 patients.

A Cox proportional hazard regression model was developed to evaluate survival adjusted by demographic and clinical factors, and a stepwise model was used for variable selection. Variables approaching statistical significance in univariate analysis (P = 0.10) and clinically meaningful variables were included in a forward stepwise selection. Potential confounders examined included gender, race, insurance, stage at diagnosis, MELD at diagnosis, Milan Criteria, receipt of locoregional therapy, HCV, hepatic encephalopathy, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, ascites, NASH, smoking history, and AFP level. Only variables reaching statistical significance at 0.05 α level were retained in the final multivariable model. Multivariable analysis rather than multivariate analysis was conducted to best assess for multiple independent variables and relationships while adjusting for potential confounders[13,14].

The Kaplan-Meier method was utilized to estimate survival distribution for two overall survival analyses, first with inclusion of all patients, and second with exclusion of liver transplant recipients. Overall survival was defined as the interval between date of HCC diagnosis and date of death due to any cause, or date of data censorship (June 6, 2013) for patients still alive.

All tests were two sided. Analysis was performed via SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

One hundred and ninety-five patients with HCC were identified for analysis, including 44 Hispanics, 61 African Americans, and 90 Whites. Patient characteristics and selected pairwise comparisons between races are summarized in Table 1. Patients were predominantly male (80.5%), White (46.1%), and had a median age of 59.7 years (range, 50.0-69.5) with 22% of patients ≥ 65 years old. The majority of patients had Medicare or Medicaid insurance (61.5%) with a small group of uninsured patients (4.1%).

Table 1.

Demographics, comorbid conditions and disease characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma patients, by race

| Patient characteristics | Total (n = 195) | Hispanic (n = 44) | African-American (n = 61) | White (n = 90) | P1 |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 59.7 ± 9.8 | 62.5 ± 12.5 | 58.7 ± 10.2 | 58.9 ± 7.7 | |

| Female (n, %) | 38, 19.5 | 11, 25.0 | 17, 27.9 | 10, 11.1 | aHW, AW |

| Insurance (n, %) | |||||

| Medicare/medicaid | 120, 61.5 | 31, 70.5 | 36, 59.0 | 53, 58.9 | |

| Private | 67, 34.4 | 12, 27.3 | 22, 36.1 | 33, 36.7 | |

| None | 8, 4.1 | 1, 2.3 | 3, 4.9 | 4, 4.4 | |

| BMI > 24.9 (n, %) | 137, 70.3 | 31, 70.5 | 44, 72.1 | 62, 68.9 | |

| Metabolic syndrome3 (n, %) | 27, 14.1 | 8, 18.2 | 3, 4.9 | 16, 18.4 | aHA, AW |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) | 31, 25.4 | 16, 55.2 | 5, 13.2 | 10, 18.2 | bHW, HA |

| On dialysis (n, %) | 7, 3.6 | 5, 11.4 | 0, 0 | 2, 2.3 | bHNH2 |

| Diabetes mellitus 2 (n, %) | 91, 46.7 | 29, 65.9 | 19, 31.1 | 43, 47.8 | bHA, aAW |

| History smoking (n, %) | 126, 65 | 16, 36.3 | 43, 70.5 | 67, 75.2 | bHW, HA; aAW |

| Current smoker (n, %) | 57, 29.4 | 2, 4.5 | 28, 45.9 | 27, 30.3 | bHW, HA; aAW |

| Triglycerides (median ± SD) | 99.5 ± 66.5 | 101.0 ± 70.2 | 111.0 ± 64.7 | 80.5 ± 65.8 | |

| History alcohol use (n, %) | 163, 83.6 | 39, 88.6 | 50, 82 | 74, 82.2 | |

| Cirrhosis characteristics | |||||

| Etiology4 | |||||

| HCV (n, %) | 132, 67.7 | 18, 40.9 | 49, 80.3 | 65, 72.2 | bHW, HA |

| HBV (n, %) | 14, 8.1 | 2, 5.0 | 8, 14.3 | 4, 5.2 | |

| ETOH (n, %) | 55, 28.2 | 11, 25.0 | 15, 24.6 | 29, 32.2 | |

| NASH (n, %) | 35, 18.0 | 15, 34.9 | 5, 8.2 | 15, 16.7 | bHA, aHW |

| Other5 (n, %) | 22, 11.3 | 11, 25 | 2, 3.3 | 9, 11.3 | 0.056 |

| MELD (median ± SD) | 11.0 ± 4.6 | 11.5 ± 4.4 | 9.0 ± 3.1 | 12.0 ± 5.1 | aHA, bAW |

| AFP | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 22.4 (6.1-217.2) | 19 (5.9-434.85) | 82 (11.9-434.8) | 12 (5.0-53.2) | |

| AFP > 200 | 49, 25.1 | 12, 27.3 | 22, 36.1 | 15, 16.7 | aHA, bAW |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (n, %) | 65, 33.3 | 16, 36.4 | 8, 13.1 | 41, 45.6 | aHA, bAW |

| Ascites (n, %) | 80, 44.5 | 23, 54.8 | 14, 26 | 43, 51.2 | aHW, HA, AW |

| HCC surveillance performed (n, %) | 113, 61.1 | 27, 65.9 | 31, 51.7 | 55, 65.5 | |

| Tumor parameters | |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||

| Median (± SD) (IQ range) | 3.0 ± 3.7 (2.0-6.0) | 3.0 ± 3.9 (2.0-5.0) | 3.0 ± 3.6 (2.0-6.0) | 3.0 ± 3.7 (2.0-6.0) | |

| > 5 cm (n, %) | 43, 26.9 | 8, 22.2 | 14, 28.6 | 21, 28 | |

| Median > 5 cm (± SD) (IQ range) | 8.0 ± 4.0 (6.0-12.0) | 13.0 ± 3.4 (7.5-13.0) | 9.5 ± 3.1 (6.0-11.0) | 7.0 ± 4.7 (6.0-8.0) | |

| Stage at diagnosis (n, %) | 99, 52.1 | 20, 45.5 | 30, 50.8 | 49, 56.3 | |

| Unifocal | 77, 40.5 | 21, 47.7 | 25, 42.4 | 31, 35.6 | |

| Multifocal | 14, 7.4 | 3, 6.8 | 4, 6.8 | 7, 8.0 | |

| Metastatic | 29, 24.2 | 9, 33.3 | 9, 23.1 | 11, 20.4 | |

| Portal vein involvement (n, %) | 35, 47.9 | 6, 54.5 | 13, 54.2 | 16, 42.1 | |

| Poorly differentiated within milan criteria (n, %) | 121, 62.1 | 28, 63.6 | 36, 59.0 | 57, 63.3 |

P values from χ2 tests (two-sided) and fischer for overall race effect followed by pairwise comparisons, for P < 0.05. A significance level of 0.05 was used for the overall race comparisons.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001, P values were not calculated for n < 5;

Given n < 5 for AA (n = 0) and W (n = 2), limited statistical tests for Hispanic to non-Hispanic with P = 0.0074;

Metabolic syndrome: Three of the following five traits per adult treatment panel III guidelines. Abdominal obesity, defined as a waist circumference in men ≥ 102 cm (40 in) and in women ≥ 88 cm (35 in): (1) serum triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or drug treatment for elevated triglycerides; (2) serum HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (1 mmol/L) in men and < 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) in women or drug treatment for low HDL-C; (3) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or drug treatment for elevated blood pressure; (4) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or drug treatment for elevated blood glucose;

Some patients with more than one listed etiology of cirrhosis;

Other: Cryptogenic, hemochromatosis, autoimmune, other not specified. H: Hispanics; A: African Americans; W: Non-Hispanic Caucasians; SD: Standard deviation; IQ: Percentile interquartile range (25%, 75%); HW: Hispanics compared to Whites; HA: Hispanics compared to African Americans; AW: African Americans compared to Whites; HNH: Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics; BMI: Body mass index; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

The observed female to male ratio was 1:2.8 in the Hispanic group, 4:5 in the African American group, and 1:2.5 in the White group, showing a higher proportion of women in the Hispanic and African American groups (P = 0.022). Among Hispanic patients, women presented at an older age in comparison to men (respectively: 71.7 ± 6.5 years vs 59.4 ± 12.6 years; P = 0.0037).

Comorbidities and modifiable risk factors

Hispanic patients demonstrated a higher prevalence of modifiable metabolic risk factors and comorbidities than African Americans or Whites. In comparison to African American and Whites, Hispanic patients had more frequent diagnoses of diabetes (P = 0.0007; P = 0.0648; P = 0.0019 on initial χ2 analysis, see appendix A), hyperlipidemia (P = 0.0004; P = 0.001), and end stage renal disease requiring dialysis (P < 0.0001), and were less likely to have a smoking history (P < 0.0001). In comparison to African Americans, Hispanic patients were more likely to meet criteria for metabolic syndrome (P = 0.0491). The three racial groups were similar with regards to age at presentation, insurance status, other comorbidities including BMI > 24.9 and history of alcohol use.

Among Hispanics, women trended towards a higher frequency of metabolic syndrome compared to men (36.4% vs 12.1%, P = 0.09).

Liver disease characteristics

Etiology and liver disease features in Hispanic patients differed from African Americans and Whites. NASH cirrhosis was significantly more common in Hispanics compared to African Americans and Whites (P < 0.0001; P = 0.026) while HCV cirrhosis was less common in Hispanics (P < 0.0001). There was a trend towards more non-viral, non-NASH cirrhosis etiologies in the Hispanic patients compared to other groups (P = 0.056).

Hispanic patients with HCC showed more evidence of advanced liver disease. In comparison to African Americans and White, ascites was more common in Hispanics (P = 0.006; P = 0.042). Hispanic patients presented with higher median MELD scores (P = 0.0159) and more hepatic encephalopathy (P = 0.0087) than African Americans. Median AFP levels were similar among groups, although Hispanic and African Americans demonstrated more variability in AFP based on interquartile range, and Hispanics were more likely to have AFP > 200 IU/mL in comparison to Whites (P = 0.035).

Among Hispanics, women had a lower prevalence of alcoholic cirrhosis compared to men (0% vs 37.93%, P = 0.0186), while the prevalence of HCV cirrhosis was similar by gender.

Tumor parameters

The three groups demonstrated similar frequency of HCC diagnosis made during active surveillance, and similar tumor parameters at presentation including stage at diagnosis, tumor size, tumor differentiation, presence of portal vein invasion, and transplant eligibility via Milan criteria at diagnosis (Table 1).

HCC treatment patterns

While median time from HCC diagnosis to time of last follow-up was similar among groups, median time from HCC diagnosis to time of first treatment was longer for African Americans in comparison to both Hispanics and Whites (median time to first line treatment; Hispanics 25.0 d (IQR 7.0-34.0 d); African Americans 39.0 d (IQR 17.0-70.0 d), Whites 32.5 d (IQR 13.0-64.0 d, P = 0.0373).

As shown in Table 2, the use of loco regional therapy (chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation) for non-metastatic HCC was similar among racial groups (P = 0.1168). The vast majority of patients (87.5%) received loco regional therapy as their initial treatment, while the remaining 12.5% of patients received other initial treatments including chemotherapy, resection, or observation. P values are not reported for the remaining 12.5% due to small numbers of patients per individual group, by race.

Table 2.

Treatment patterns for non-metastatic patients at diagnosis: First line treatment patterns for non-metastatic patients by race

| First line treatment characteristics | Total (n = 176)1 | Hispanic (n = 41) (n, %) | African American (n = 55) (n, %) | White (n = 80)1 (n, %) | P2 |

| Surgery | 2 | 0, 0 | 2, 3.6 | 0, 0 | |

| Liver directed | 154 | 38, 92.7 | 48, 87.2 | 68, 85 | |

| Chemotherapy | 6 | 1, 2.4 | 2, 3.6 | 3, 3.8 | |

| Observation | 6 | 0, 0 | 1, 1.8 | 4, 5 | |

| Lost to follow-up | 7 | 2, 4.9 | 2, 3.6 | 4, 5 |

One patient missing information;

P values from χ2 tests (two-sided) and fischer for overall race effect followed by pairwise comparisons, for P < 0.05. A significance level of 0.05 was used for the overall race comparisons.

There was no difference in HCC presentation within Milan Criteria, listing for transplant, receipt of tumor exception points, or liver transplantation for patients meeting Milan Criteria among the three ethnic/racial groups (Table 3). However, once listed, African Americans were more frequently removed from the transplant list due to HCC progression and death (64.7% vs 25.8%, P = 0.0084) and were less likely to receive liver transplantation (35.3% vs 71%, P = 0.0165) compared to Whites. Hispanics did not differ significantly from Whites or African Americans with regard to being transplanted once listed, or removed from the list (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment patterns for non-metastatic patients at diagnosis: Transplantation patterns by race

| Transplantation patterns | Total listed | Hispanic | African American | White | P2 |

| Met milan criteria | 121 | 28 | 36 | 57 | |

| Transplanted | 341, 1.4% | 10, 35.7% | 6, 16.7% | 181, 31.6% | |

| Listed | 68 | 20 | 17 | 31 | |

| Tumor exception points | 33, 48.5% | 10, 50% | 6, 35.3% | 17, 48.4% | |

| Transplanted | 381, 55.9% | 10, 50% | 6, 35.3% | 221, 71%1 | aAW |

| Removed from list | 28, 41.1% | 9, 45% | 11, 64.7% | 8, 25.8% | bAW |

| Death | 7 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| Progression | 10 | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| Transfer of care | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Other | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

Four patients initially outside of Milan criteria, subsequently listed and transplanted after reassessment and locoregional treatment;

P values from χ2 tests (two-sided) and fischer for overall race effect followed by pairwise comparisons, for P < 0.05. A significance level of 0.05 was used for the overall race comparisons.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001. P values were not calculated for n < 5. AW: African American compared to Whites.

Overall survival

Forty-nine of the 195 patients died from all causes during the study period (Hispanic n = 9; African American n =15; Whites n = 25). The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 563 d and was similar among racial groups. In a multivariable analysis examining possible confounders, three variables were identified as independently related to survival including HCV, metabolic syndrome, and race. However, when all three variables were entered in a stepwise fashion for model building, only race was found to be predictive of survival.

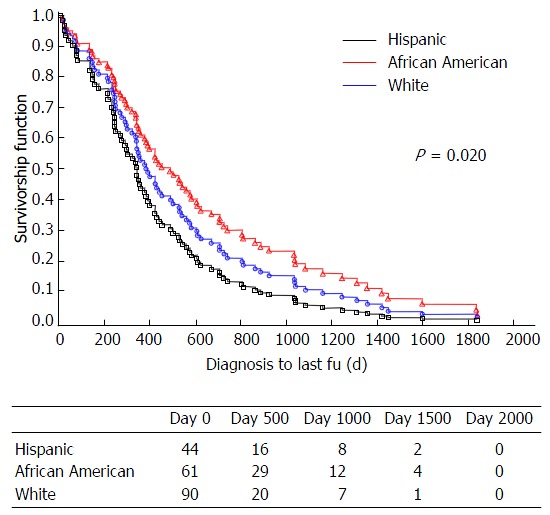

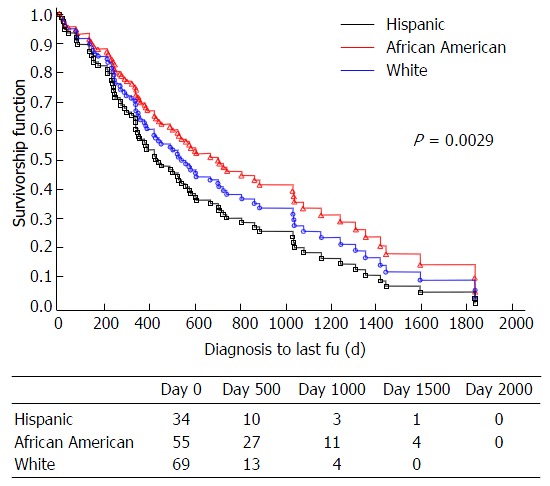

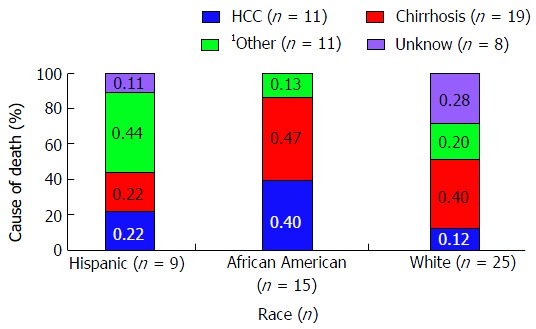

Hispanic patients appeared to have poorer survival compared to both African American and Whites (log-rank test for overall differences by race: P = 0.0220) (Figure 1). The hazard ratio for death was 1.52 (95%CI: 0.354, 1.223), for Hispanics in comparison to African Americans and 1.36 (95%CI: 0.739-2.511), for Hispanic in comparison to Whites. After excluding patients who underwent liver transplantation, a second multivariable model adjusting for the factors mentioned above confirmed that Hispanics with HCC had the highest mortality rate (log-rank test for overall differences by race: P = 0.0029) (Figure 2). Cause of death was similar for all groups for cases in which the cause of death could be discerned (Figure 3), with similar frequency of death due to HCC (n = 11) vs liver cirrhosis (n = 19) vs other (n = 11) in Hispanics, African Americans, and Whites.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted survival curve stratified in patients with hepato-cellular carcinoma by race from time of presentation to time of death or censorship (with numbers of subject at risk). Hispanic (n = 44), African American (n = 61), Whites (n = 90). P-value was obtained by the log-rank test.

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves by race after exclusion of patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation (with numbers of subjects at risk). Hispanic (n = 34), African American (n = 55), Whites (n = 69). P-value was obtained with the use of the log-rank test.

Figure 3.

Distribution of cause of death in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma by race. There was no difference in HCC (P = 0.1051), cirrhosis (P = 0.6162), or other (P = 0.0581) as cause of death between Hispanics, African Americans, and White. 1Cause of death other includes: Immediate complications post liver transplant (n = 3), sepsis (n = 3), complications from second malignancy (n = 2), cardiogenic shock (n = 1), PEA (n = 1), intracerebral hemorrhage (n = 1). Of Hispanic patient (n = 4), immediate complications post liver transplant (n = 2), cardiogenic shock (n = 1), complications from a second malignancy (n = 1). Fischers pairwise comparison not performed due to n < 5 per group. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

Hispanics with HCC had significantly shorter survival in comparison to both African American and Whites, with race as the only independent predictor of survival in multivariable analysis. This observation is consistent with previous studies showing that Hispanic ethnicity was an independent risk factor for HCC-related mortality, with shorter 5 year survival[9,10] in Hispanic patients with HCC compared to White and Asian counterparts, and higher mortality rates in Hispanics aged 50-64[15].

A substantive body of prior research has shown that health disparities, barriers to care, socioeconomic characteristics, and later diagnosis of more advanced malignancy impact on survival in minority groups[16-18]. An important contribution of the current study was that we found no evidence that reduced survival in Hispanics with HCC was related to differences in access to care; groups were similar with regard to insurance status, age at diagnosis, HCC diagnoses made during active surveillance, and tumor parameters at presentation including stage and tumor grade at diagnosis.

Little is known about features of patients with HCC that might contribute to disparate outcomes by race. Data from the current study shows important and intriguing differences in HCC presentation and disease characteristics for Hispanics. Characteristics that distinguished Hispanic patients included significantly higher rates of comorbidities and modifiable risk factors for liver disease such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, as well as a greater prevalence of NASH and ESRD. Hispanics also had evidence of more advanced liver disease with higher rates of ascites than African Americans and Whites and higher MELD scores and more hepatic encephalopathy than African Americans.

The clinical correlates of HCC in Hispanics provide a context to consider potential causes for the shorter overall survival in Hispanics. Patients with HCC are at risk for complications and mortality from cirrhosis, HCC, and other comorbidities. Consistent with prior studies, we found that Hispanic patients had higher rates of comorbidities including metabolic syndrome[19,20] and ESRD[21-23]. Our data builds on existing literature by showing that these differences persist in patients with HCC. Moreover, metabolic disease might contribute to the development of HCC and to poorer outcomes in Hispanics. There is increasing evidence that diabetes and obesity are individually associated with significant risk of HCC development[24-26], and Hispanics appear to demonstrate a stronger association between diabetes and HCC compared to non-Hispanics[27]. A longitudinal study reported that diabetic Hispanics had a 3.3 × higher risk of HCC development compared to non-diabetic Hispanics, and that there was a 2.17 × higher risk of HCC for diabetic non-Hispanics compared to non-diabetic counterparts[28].

In addition to higher rate of comorbidities and modifiable risk factors, Hispanics had more complications of portal hypertension and compared to African Americans had higher MELD scores at presentation, indicating more advanced liver disease. This is consistent with national data reporting a higher prevalence of chronic liver disease, more advanced disease features at presentation, and higher liver disease related mortality in Hispanics[29-31]. Although chronic liver disease is the 6th most common cause of death in Hispanic populations in 2010 per the United States National Center for Health Statistics data, it is not within the top ten causes of death for African American or White populations. Mortality rates from chronic liver disease are almost 50% higher in Hispanics than non-Hispanics[32]. One potential explanation may be that increased comorbidities in Hispanics could contribute to higher chronic liver disease mortality. Recent SEER data found parallel mortality trends for diabetes, chronic liver disease, and HCC by state; states with high HCC mortality also demonstrated elevated mortality rates for diabetes and liver disease, including cirrhosis[15]. Racial/ethnic biologic differences in cirrhosis pathogenesis might also contribute; Hispanics with HCV appear at significantly higher risk for cirrhosis and HCC development compared to non-Hispanic Whites and African Americas, independently of BMI, diabetes, HCV treatment and genotype[33]. Additionally, Hispanics with HCV cirrhosis showed lower median time to cirrhosis at a younger age[34], and higher rates of cirrhosis mortality for Hispanics in both the United States and Mexico[29-31]. The finding of higher rates of ESRD in Hispanics in the current study is consistent with prior literature reporting higher incidence of ESRD in Hispanics than non-Hispanics, and a higher risk of kidney failure despite similar prevalence of stage 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease[22,23,35,36]. Renal failure is associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with cirrhosis[37]. It is intriguing that Hispanics carry a disproportionate burden of ESRD and cirrhosis severity and incidence, although ESRD did not independently predict shorter survival in our study.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the United States[38-40] and is increasingly being recognized as an important cause of cirrhosis and HCC[41] with higher prevalence in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic[42]. Recent data also suggest NAFLD’s role in hepatocarcinogenesis in the absence of cirrhosis[40]. NASH comprises a subgroup of NAFLD with hepatocyte injury and inflammation, and is considered to be the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. In the current series, NASH was the second leading cause of liver disease in Hispanics with HCC, accounting for 34% of cases. Consistent with prior studies, we found Hispanics demonstrated notable differences in cirrhosis etiologies compared to non-Hispanics, including higher rates of NASH[43,44] and autoimmune cirrhosis[45], and lower incidence of HCV cirrhosis[46]. Additionally, we observed that NASH was particularly prevalent in Hispanic women compared to Hispanic men (72.7% vs 21.9%). Although the risk of HCC development in NAFLD is lower than with HCV[47], NASH is poised to become the primary etiology for cirrhosis and HCC in developed countries over the next decade. One new observation from our study is that Hispanics and Whites with HCC had similar rates of diabetes and metabolic syndrome, although Hispanics had more NASH cirrhosis and hypertriglyceridemia. This suggests that Hispanics may have differences in NAFLD progression, NASH pathogenesis and a greater susceptibility towards cirrhosis. A role for biologic differences in cirrhosis pathogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis unique to Hispanics has been suggested by prior studies demonstrating that Hispanic patients with NASH, NAFLD, and hepatitis C[48] demonstrate more fibrosis and higher rate of aminotransferase abnormalities in comparison to other ethnic groups[49,50]. The high prevalence of metabolic disease and NASH in Hispanics with HCC has a critically important implication. Early identification of Hispanics with risk factors for NASH and intervention to modify metabolic risk factors could have a major impact on reducing the development of HCC in Hispanics. Specifically, elimination of diabetes and metabolic syndrome could significantly decrease HCC incidence across all ethnic groups, but with largest reduction in Hispanics. Additionally, targeted HCC screening for Hispanics with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and NASH risk factors for NASH could also improve diagnosis, timely treatment, and survival for Hispanics with HCC.

The retrospective design of the current study made it difficult to assess whether reduced survival in Hispanics with HCC was related to increased mortality from complications of cirrhosis, HCC, or comorbid conditions. It is likely that synergy between biologic, genetic, and environmental factors may contribute to racial differences in cirrhosis pathogenesis, HCC development, and survival. Recent proteomic and tissue microarray studies have demonstrated racial and regional differences in molecular pathogenesis of cirrhosis and HCC, including variations of molecular signatures for HCV induced HCC[51] unique to African Americans compared to Whites, down-regulation of p53 and MDM2 in Americans compared to South Koreans[52], higher prevalence of PNPLA3 polymorphisms associated with high NAFLD susceptibility and worse survival in Hispanics[53] and greater expression of genetic polymorphisms predisposing towards higher NASH severity in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics[8]. Genetic and biologic differences are associated with susceptibility to increased fibrosis and inflammation in NAFLD, NASH and HCV, influencing more aggressive cirrhosis progression and hepatocarcinogenesis[48-50,54-56]. Racial and ethnic differences modulating insulin resistance have also been identified; compared to non-Hispanics, Hispanics express a higher frequency of an insulin receptor gene regulator (high-mobility group AT-hook, or HMGA1) associated with higher BMI, lower HDL, and type 2 diabetes[57]. While our study did not include biologic correlates, given the paucity of Hispanic specific information, studies comparing Hispanic tumor and cirrhosis samples to other multi-ethnic HCC and cirrhotic cohorts are necessary to better understand ongoing racial disparities in HCC and cirrhosis mortality and progression.

Despite being one of the largest single institution studies of HCC in Hispanics, African Americans and Whites, the major limitation of the present study was the retrospective design. The study identified important clinical factors associated with HCC in Hispanics. However, it was unable to discern the cause of reduced overall survival in Hispanics with HCC. Moreover, single center data might not be applicable to all Hispanic populations. Prospective studies with molecular analyses are needed to determine the relative contributions of co-morbidities, cirrhosis, HCC and biologic correlative information to the reduced overall survival in Hispanics.

In conclusion, the current study provides important new insights into clinical factors distinguishing Hispanics with HCC. Hispanics with HCC present with a higher prevalence of modifiable metabolic risk factors, more advanced liver disease, and shorter survival compared to African Americans and Whites. Increased mortality in Hispanics with HCC may be explained by compounding risk from metabolic comorbidities, NASH cirrhosis, and unique biologic gene-environment interactions influencing higher susceptibility towards NAFLD development, and more aggressive cirrhosis progression and hepatocarcinogenesis. Further clinical, epidemiologic, and molecular data are necessary to determine the relative contributions of modifiable comorbidities such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and NASH to HCC pathogenesis in Hispanics. Development of prospective multi-institutional HCC databases with specimen sharing is essential. There is an additional need for prospective case controlled studies, and therapeutic clinical trials with proportional representation of Hispanics to assess the impact of modifying comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, ESRD, diabetes, and NASH through lifestyle and medical management upon cirrhosis and HCC progression in Hispanic and non-Hispanics. Identification of clinical factors associated with HCC in Hispanics provides direction for public health efforts at HCC prevention through intervening on modifiable risk factors, targeted HCC screening for high risk ethnic populations, and more timely HCC treatment and management in this population.

COMMENTS

Background

There is a dearth of information about hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) race specific risk factors and disease characteristics in Hispanic patients, compared to African American and White patients, despite higher incidence and mortality rates. This is one of the largest published single institution retrospective studies of Hispanic, African American, and White patients treated for HCC at an urban tertiary academic medical center.

Research frontiers

The results of this study contribute to new insights and a deeper understanding of racial disparities in HCC incidence, cirrhosis progression and mortality in Hispanic patients, compared to African American and White patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The results of this study demonstrate significant differences in survival and modifiable risk factors for Hispanic patients compared to other racial groups, with Hispanic patients showing lower survival, more advanced liver disease, and higher incidence of modifiable risk factors including metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and end stage renal disease. This is consistent with prior data suggesting compounding risks unique to Hispanic patients, including modifiable risk factors, biologic differences in cirrhosis and NASH pathogenesis, and gene-environmental interactions influencing a higher susceptibility towards hepatocarcinogenesis and more aggressive cirrhosis progression.

Applications

Identification of clinical factors associated with HCC in Hispanics provides direction for public health efforts at HCC prevention through intervening on modifiable risk factors, targeted HCC screening for high risk ethnic populations, and more timely HCC treatment and management in this population.

Terminology

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; OS: Overall survival; UIC: University of Illinois, Chicago; AASLD: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; BMI: Body mass index; ATP: Adult treatment panel; ESRD: End stage renal disease; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Peer-review

An interesting observation study for the clinical outcome between HCC in Hispanics to those of African Americans and Whites. A clearly data presentation and manuscript written.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This was a retrospective study which was approved by the University of Illinois IRB as an expedited review, under expedited category 5 (Protocol 2005-0283). As such, it was granted a waiver of informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Informed consent statement: This study was approved under expedited category 5 (Protocol 2005-0283). As such, it was granted a waiver of informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial relationships to disclose.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: September 28, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Article in press: January 18, 2017

P- Reviewer: Chiu KW, Chuang WL, Ma L, Wong GLH S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GLOBOCAN 2008. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/populations/factsheet.asp?uno=900.

- 3.Ahmed F, Perz JF, Kwong S, Jamison PM, Friedman C, Bell BP. National trends and disparities in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, 1998-2003. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen MH, Whittemore AS, Garcia RT, Tawfeek SA, Ning J, Lam S, Wright TL, Keeffe EB. Role of ethnicity in risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:820–824. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00353-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Census Brief 2010: The Hispanic Population. 2010. Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- 6.El-Serag HB, Lau M, Eschbach K, Davila J, Goodwin J. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hispanics in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1983–1989. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez AG, Weiss NS, Holden AE, Suarez L, Cooper SP, Munoz E, Naylor SL. Incidence and risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Texas Latinos: implications for prevention research. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, Goding-Sauer A, Pinheiro PS, Martinez-Tyson D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:457–480. doi: 10.3322/caac.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Dickie LA, Kleiner DE. Hepatocellular carcinoma confirmation, treatment, and survival in surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registries, 1992-2008. Hepatology. 2012;55:476–482. doi: 10.1002/hep.24710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M. Hepatitis C virus infection, age, and Hispanic ethnicity increase mortality from liver cancer in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidalgo B, Goodman M. Multivariate or multivariable regression? Am J Public Health. 2013;103:39–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a primer for readers of medical research. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:644–650. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altekruse SF, Henley SJ, Cucinelli JE, McGlynn KA. Changing hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and liver cancer mortality rates in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:542–553. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathur AK, Osborne NH, Lynch RJ, Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB, Sonnenday CJ. Racial/ethnic disparities in access to care and survival for patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145:1158–1163. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Artinyan A, Mailey B, Sanchez-Luege N, Khalili J, Sun CL, Bhatia S, Wagman LD, Nissen N, Colquhoun SD, Kim J. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status influence the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:1367–1377. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong LL, Hernandez BY, Albright CL. Socioeconomic factors affect disparities in access to liver transplant for hepatocellular cancer. J Transplant. 2012;2012:870659. doi: 10.1155/2012/870659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boden-Albala B, Cammack S, Chong J, Wang C, Wright C, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Diabetes, fasting glucose levels, and risk of ischemic stroke and vascular events: findings from the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1132–1137. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez F, Naderi S, Wang Y, Johnson CE, Foody JM. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome in young Hispanic women: findings from the national Sister to Sister campaign. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:81–86. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benabe JE, Rios EV. Kidney disease in the Hispanic population: facing the growing challenge. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:789–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Fan D, Ordoñez J, Lash JP, Chertow GM, Go AS. Risks for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular events, and death in Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2892–2899. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1–12. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calle EE, Teras LR, Thun MJ. Obesity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2197–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200511173532020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Javadi F. The association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C, Wang X, Gong G, Ben Q, Qiu W, Chen Y, Li G, Wang L. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1639–1648. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setiawan VW, Hernandez BY, Lu SC, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, Le Marchand L, Henderson BE. Diabetes and racial/ethnic differences in hepatocellular carcinoma risk: the multiethnic cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:pii: dju326. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendy Setiawan PD. Multiethnic Cohort Study Analysis: Diabetes Identified as Risk Factor for Liver Cancer Across Ethnic Groups. AACRSixth AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held December 6-9; Paper presented at. 2013. Available from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/12/131209084147.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores YN, Yee HF, Leng M, Escarce JJ, Bastani R, Salmerón J, Morales LS. Risk factors for chronic liver disease in Blacks, Mexican Americans, and Whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999-2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2231–2238. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart SH. Racial and ethnic differences in alcohol-associated aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase elevation. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2236–2239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dufour MC. The critical dimension of ethnicity in liver cirrhosis mortality statistics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asrani SK, Larson JJ, Yawn B, Therneau TM, Kim WR. Underestimation of liver-related mortality in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:375–382.e1-2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Serag HB, Kramer J, Duan Z, Kanwal F. Racial differences in the progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected veterans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1427–1435. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Torres M, Ríos-Bedoya CF, Rodríguez-Orengo J, Fernández-Carbia A, Marxuach-Cuétara AM, López-Torres A, Salgado-Mercado R, Bräu N. Progression to cirrhosis in Latinos with chronic hepatitis C: differences in Puerto Ricans with and without human immunodeficiency virus coinfection and along gender. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:358–366. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000210105.66994.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lora CM, Daviglus ML, Kusek JW, Porter A, Ricardo AC, Go AS, Lash JP. Chronic kidney disease in United States Hispanics: a growing public health problem. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:466–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer MJ, Go AS, Lora CM, Ackerson L, Cohan J, Kusek JW, Mercado A, Ojo A, Ricardo AC, Rosen LK, et al. CKD in Hispanics: Baseline characteristics from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) and Hispanic-CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:214–227. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belcher JM, Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Bhogal H, Lim JK, Ansari N, Coca SG, Parikh CR. Association of AKI with mortality and complications in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;57:753–762. doi: 10.1002/hep.25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H, Day C, Marchesini G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol. 2010;53:372–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Starley BQ, Calcagno CJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51:1820–1832. doi: 10.1002/hep.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torres DM, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and noncirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma: fertile soil. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:30–38. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White DL, Kanwal F, El-Serag HB. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk for hepatocellular cancer, based on systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1342–1359.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Determinants of the association of overweight with elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:71–79. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Negro F, Hallaji S, Younossi Y, Lam B, Srishord M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals in the United States. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012;91:319–327. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182779d49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browning JD. Statins and hepatic steatosis: perspectives from the Dallas Heart Study. Hepatology. 2006;44:466–471. doi: 10.1002/hep.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong RJ, Gish R, Frederick T, Bzowej N, Frenette C. The impact of race/ethnicity on the clinical epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:155–161. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318228b781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ditah I, Ditah F, Devaki P, Ewelukwa O, Ditah C, Njei B, Luma HN, Charlton M. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 through 2010. J Hepatol. 2014;60:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972–1978. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kallwitz ER, Layden-Almer J, Dhamija M, Berkes J, Guzman G, Lepe R, Cotler SJ, Layden TJ. Ethnicity and body mass index are associated with hepatitis C presentation and progression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bambha K, Belt P, Abraham M, Wilson LA, Pabst M, Ferrell L, Unalp-Arida A, Bass N. Ethnicity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:769–780. doi: 10.1002/hep.24726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kallwitz ER, Kumar M, Aggarwal R, Berger R, Layden-Almer J, Gupta N, Cotler SJ. Ethnicity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an obesity clinic: the impact of triglycerides. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1358–1363. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dillon ST, Bhasin MK, Feng X, Koh DW, Daoud SS. Quantitative proteomic analysis in HCV-induced HCC reveals sets of proteins with potential significance for racial disparity. J Transl Med. 2013;11:239. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song TJ, Fong Y, Cho SJ, Gönen M, Hezel M, Tuorto S, Choi SY, Kim YC, Suh SO, Koo BH, et al. Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in American and Asian patients by tissue array analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:84–88. doi: 10.1002/jso.23036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hassan MM, Kaseb A, Etzel CJ, El-Serag H, Spitz MR, Chang P, Hale KS, Liu M, Rashid A, Shama M, et al. Genetic variation in the PNPLA3 gene and hepatocellular carcinoma in USA: risk and prognosis prediction. Mol Carcinog. 2013;52 Suppl 1:E139–E147. doi: 10.1002/mc.22057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lade A, Noon LA, Friedman SL. Contributions of metabolic dysregulation and inflammation to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatic fibrosis, and cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:100–107. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guzman G, Brunt EM, Petrovic LM, Chejfec G, Layden TJ, Cotler SJ. Does nonalcoholic fatty liver disease predispose patients to hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1761–1766. doi: 10.5858/132.11.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, El-Serag HB, Jiao L, Lee J, Moore D, Franco LM, Tavakoli-Tabasi S, Tsavachidis S, Kuzniarek J, Ramsey DJ, et al. WNT signaling pathway gene polymorphisms and risk of hepatic fibrosis and inflammation in HCV-infected patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pullinger CR, Goldfine ID, Tanyolaç S, Movsesyan I, Faynboym M, Durlach V, Chiefari E, Foti DP, Frost PH, Malloy MJ, et al. Evidence that an HMGA1 gene variant associates with type 2 diabetes, body mass index, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in a Hispanic-American population. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12:25–30. doi: 10.1089/met.2013.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]