Abstract

Background

We used data from 4 years of pediatric severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) sentinel surveillance in Blantyre, Malawi, to identify factors associated with clinical severity and coviral clustering.

Methods

From January 2011 to December 2014, 2363 children aged 3 months to 14 years presenting to the hospital with SARI were enrolled. Nasopharyngeal aspirates were tested for influenza virus and other respiratory viruses. We assessed risk factors for clinical severity and conducted clustering analysis to identify viral clusters in children with viral codetection.

Results

Hospital-attended influenza virus–positive SARI incidence was 2.0 cases per 10 000 children annually; it was highest among children aged <1 year (6.3 cases per 10 000), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected children aged 5–9 years (6.0 cases per 10 000). A total of 605 SARI cases (26.8%) had warning signs, which were positively associated with HIV infection (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–3.9), respiratory syncytial virus infection (aRR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.3–3.0) and rainy season (aRR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6–3.8). We identified 6 coviral clusters; 1 cluster was associated with SARI with warning signs.

Conclusions

Influenza vaccination may benefit young children and HIV-infected children in this setting. Viral clustering may be associated with SARI severity; its assessment should be included in routine SARI surveillance.

Keywords: children, SARI, Africa, viral coinfection, influenza

It is estimated that, worldwide, the case-fatality rate of severe pneumonia in children aged <5 years is 8.9%, which, in 2011, amounted to 1.26 million deaths [1]. Much of this burden falls on sub-Saharan Africa, where severe acute respiratory infection (SARI), including pneumonia, is a leading cause of childhood hospital attendance and death [2]. Although laboratory diagnostic facilities are rarely available in such settings, sentinel surveillance using multiplex molecular diagnostic assays has recently provided considerable insight into the true burden of disease and the complexity of SARI etiology. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza viruses, rhinoviruses, influenza viruses, and adenovirus have been commonly detected in SARI surveillance across the African continent [3–8]. While there are a few viruses for which detection in respiratory disease cases is likely causal (eg, influenza virus and RSV) [9, 10], for other commonly identified viruses causality has been difficult to determine. Use of multiplex assays has led to an increasing realization that children with SARI commonly carry multiple viral pathogens that may potentially contribute to disease.

In the context of a low-income population with multiple drivers of immune compromise (eg, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, malnutrition, and malaria) [11], we conducted active surveillance at a large urban teaching hospital in Malawi to estimate the incidence of childhood SARI and explore the association of SARI clinical severity with HIV infection and clustering of respiratory viral coinfection. While previous studies have focused on children aged <5 years, we included children aged 3 months to 14 years in our analysis, to better capture the total burden and identify age groups particularly at risk.

METHODS

Study Site, Population, and Study Design

QECH is the only government inpatient facility for Blantyre (population, approximately 500 000 children aged <15 years); it offers care free at the point of delivery. Overall, 13% of children aged <5 years in Malawi are moderately to severely underweight, and 4% are experiencing wasting; 80.9% of children aged 12–23 months have received all Expanded Program on Immunization vaccinations [12]. There is no national routine influenza vaccination in Malawi. In 2010, a monovalent vaccine campaign targeting 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus (A[H1N1]pdm09) achieved 74% coverage in pregnant women and 7% of the overall population [13]. An estimated 2.5% of children aged <15 years are HIV infected [14]; the HIV prevalence in children aged <5 years on QECH nonsurgical pediatric wards is estimated at 6%. Blantyre has 2 distinct weather seasons, a rainy season (January–April) and a cool dry season (May–August). Overall, 25.2% of Paediatric Accident and Emergency Unit (PAEU) patients have a malaria parasite–positive blood slide; malaria presentations to the PAEU peak from December to May.

Patients aged 3 months to 14 years presenting during surveillance hours (weekdays, from 8:00 am to 1:00 pm) from January 2011 through December 2014 were screened. Consecutive patients fulfilling the SARI case definition were recruited (maximum, 5 per day). Demographic and clinical data were captured through an electronic data collection system [15]. Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) were obtained and tested for influenza viruses; from 2011 to 2013, NPAs were also tested by multiplex assay for respiratory pathogens. Thick blood films for detection of malaria parasites were performed for all children.

SARI was defined as (1) an acute illness with symptom onset <7 days and (2) a reported or recorded fever of ≥38°C (or hypothermia in children <6 months). Additional criteria for SARI varied by age. In children aged <6 months, additional criteria were (3) cough or apnea or (4) any respiratory symptom requiring hospitalization. In children aged 6–59 months, an additional criterion was (3) clinician-diagnosed lower respiratory infection. In children aged 6–14 years, additional criteria were (3) cough or sore throat and (4) shortness of breath or difficulty breathing. SARI with warning signs was considered clinically more severe and defined as the occurrence of one of the following: admission to the hospital, chest recession, or blood oxygen saturation of ≤90%. In this resource-limited setting, some patients with severe illness requiring admission were sent home. Thus, hospital attendance (not admission) was required for study enrollment.

Laboratory Procedures

NPAs were stored at −80°C in Universal Transport Medium (Copan, Brescia, Italy) [16] and tested in batches for influenza viruses by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Total nucleic acids were extracted from 300-µL aliquots of each specimen with the Qiagen BioRobot Universal System, using the QIAamp One-For-All nucleic acid kit (Qiagen, Manchester, United Kingdom). The quantity of nucleic acid used per reaction was 5 µL for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Human Influenza real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel (CDC Influenza Division), which detects influenza A and B viruses and influenza A subtypes H1, H3, 2009H1, and H5N1, and 10 µL for the FTD respiratory pathogens 33 kit (Fast-track Diagnostics, Luxembourg). Details on sample processing with by FTD real-time RT-PCR are provided in Appendix 1. HIV serostatus was assessed by the rapid test (Alere Determine HIV-1/2 and Trinity Biotech Uni-Gold HIV) according to World Health Organization guidelines [17]. PCR for detection of HIV RNA was performed in children aged 3–11 months who had a positive HIV rapid test. HIV infection was defined on the basis of positive results of an HIV rapid test (in the absence of an HIV-negative PCR); data were not collected on HIV exposure.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee (approval RETH000790), the University of Malawi College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (COMREC; approval 958), and the CDC through reliance on the COMREC. Informed consent was obtained from guardians of all study participants.

Data Analysis

Numerators for minimum SARI incidence estimates were generated by summing the number of cases resident in Blantyre within strata of age category and HIV status. Numerators were adjusted by multiplying by the reciprocal of the daily proportion of recruited cases among all SARI cases attending the PAEU. Denominators for HIV and age strata were derived by applying age-specific HIV prevalence estimates to census figures for Blantyre District's population aged 0–14 years [18]. The former were obtained by apportioning the total HIV prevalence among Malawian children aged <15 years [14] according to the age distribution of pediatric HIV infections in Mozambique, which borders Malawi and has a similarly severe HIV epidemic [19, 20]. Estimates of age-specific HIV prevalence were unavailable for Malawi for the study period. The incidence was obtained by dividing numerators by denominators and multiplying by 10 000; HIV-associated incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated by dividing the incidence in HIV-infected strata by the incidence in HIV-uninfected strata; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of incidence and HIV-associated IRRs were generated with 1000 bootstrap samples.

Data analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Temporal trends in weekly sample counts for SARI cases were assessed by plotting 5-week moving averages of sample counts by recruitment week. We developed 2 logistic regression models with a binary outcome factor for the child's clinical status. The first outcome represented SARI with warning signs (ie, clinical markers of very severe illness) versus SARI without warning signs. The second outcome represented influenza virus–positive SARI versus influenza virus–negative SARI. Autoregressive correlation of residuals was removed by introducing a patient-level kernel weighted moving average of the prior probability of case status. Parsimonious models were developed by stepwise logistic regression, retaining age, sex a priori, and explanatory factors with a 2-sided P value of <.05. Adjusted relative risk ratios for factors associated with the outcomes were derived from these models.

Detection of multiple viruses in SARI is common, with many possible combinations of viral carriage. Conventional statistical techniques (eg, regression models, covariance matrices, and temporal plots) have limited capacity to quantify, characterize or identify factors associated with viral carriage groupings. To assess multiple virus carriage clusters in our setting, we performed nearest-neighbor discrete hierarchical cluster analysis in patients with viral codetection, using the Gower distance [21]. Distance was based on similarity of viral pathogens detected in the nasopharynx of patients with SARI; each patient was a member of only 1 cluster. We defined clusters as those that increased the R2 value by ≥0.05 (using the Ward method); to improve precision, 10% of observations with the lowest densities were discarded. Using univariate logistic regression, we identified factors associated with cluster membership.

RESULTS

SARI Population

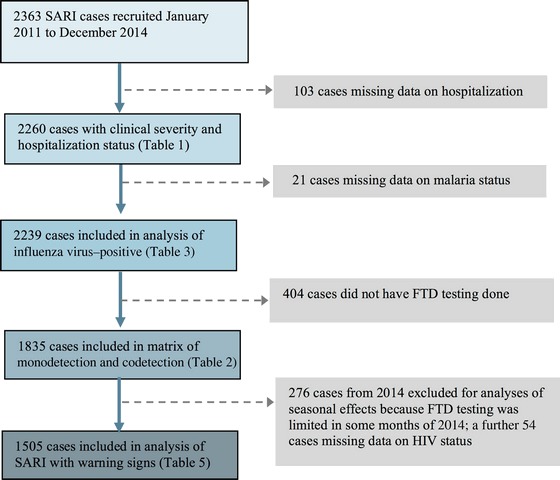

From 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2014, 2363 SARI cases (median age, 15 months; interquartile range [IQR], 8–27 months) were recruited. In total, 605 of 2260 SARI cases (26.8%) had clinical warning signs (Table 1; the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram is available in Appendix 2). Warning signs were determined as follows: 489 of 605 (80.8%) were hospitalized (median duration of stay, 2 days [IQR, 1–3 days]), 37 of 605 (6.1%) had a blood oxygen saturation level of <90%, 75 of 605 (12.4%) had chest recession, and 4 of 605 (<1%) had both of these clinical features. In cases aged 3 to <12 months, 17 of 247 (6.9%) had a positive HIV test result, compared with 29 of 563 (5.2%) aged 12 to <36 months, 45 of 1050 (4.3%) aged 36–59 months, 19 of 241 (7.9%) aged 5–9 years, and 18 of 103 (17.5%) aged 10–14 years. Eight of 17 HIV infections in cases aged 3 to <12 months (47.1%) were confirmed by PCR.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Pediatric Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI), by Clinical Severity and Hospitalization Status, Blantyre, Malawi, 2011–2014

| Characteristic | Overall, No. (%)a | SARI Without Warning Signs,b No. (%) |

SARI With Warning Signs, No. (%) |

P Valuec | Nonhospitalized SARI, No. (%) |

Hospitalized SARI, No. (%) |

P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, no. | 2260 | 1655 | 605 | 1771 | 489 | ||

| Female | 1134 (43.0) | 850 (51.4) | 205 (33.9) | .011 | 855 (48.3) | 205 (41.9) | .017 |

| Age | |||||||

| 3 mo to <6 mo | 265 (11.7) | 207 (12.6) | 58 (9.6) | 240 (12.8) | 43 (8.8) | ||

| 6 mo to <12 mo | 584 (25.8) | 423 (25.6) | 161 (26.6) | 483 (25.8) | 129 (26.4) | ||

| 12 mo to <36 mo | 1077 (47.7) | 777 (46.9) | 300 (49.6) | 862 (46.0) | 244 (49.9) | ||

| 36 mo to <60 mo | 248 (10.9) | 192 (11.6) | 56 (9.3) | 212 (11.3) | 44 (9.0) | ||

| 5 y to 14 y | 86 (3.8) | 56 (3.4) | 30 (4.9) | .057 | 77 (4.1) | 29 (5.9) | .023 |

| Season of recruitment | |||||||

| Sep–Dec | 739 (32.7) | 554 (33.4) | 185 (30.6) | 648 (34.6) | 136 (27.8) | ||

| Jan–Apr (rainy) | 783 (34.6) | 521 (31.4) | 262 (43.3) | 587 (31.3) | 222 (45.4) | ||

| May–Aug | 738 (32.7) | 580 (35.0) | 158 (26.1) | <.001 | 639 (34.1) | 131 (26.8) | <.001 |

| HIV positived | 120 (5.6) | 65 (4.2) | 55 (9.8) | <.001 | 80 (4.6) | 48 (10.6) | <.001 |

| Weight-for-age z score <2 SDd | 449 (20.9) | 325 (20.2) | 124 (22.9) | .169 | 353 (20.5) | 98 (22.4) | .370 |

| Malaria parasite positived | 78 (3.5) | 47 (2.9) | 31 (5.3) | .007 | 52 (2.9) | 27 (5.6) | .006 |

| RSV PCR positived | 220 (11.9) | 130 (9.4) | 90 (19.9) | <.001 | 146 (9.9) | 74 (20.9) | <.001 |

| Influenza virus PCR positive | 258 (11.4) | 199 (12.0) | 59 (9.8) | .133 | 217 (11.6) | 50 (10.2) | .399 |

| Yeara,e | |||||||

| 2011 | 25 (8.8) | 10 (7.3) | 15 (9.3) | .531 | 11 (6.1) | 14 (11.8) | .079 |

| 2012 | 30 (6.2) | 28 (6.7) | 3 (2.8) | .121 | 29 (6.5) | 2 (2.5) | .167 |

| 2013 | 141 (16.2) | 111 (15.6) | 30 (19.5) | .229 | 117 (15.8) | 24 (18.6) | .431 |

| 2014 | 70 (10.5) | 59 (12.0) | 11 (6.0) | .024 | 60 (11.8) | 10 (6.1) | .040 |

| Influenza virus type(s)/subtype | |||||||

| A | |||||||

| H1N1pdm09 | 44 (2.0) | 25 (1.5) | 19 (3.1) | 28 (1.5) | 18 (3.7) | ||

| H3N2 | 106 (4.7) | 90 (5.4) | 16 (2.6) | 101 (5.4) | 11 (2.3) | ||

| Unsubtyped | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (<0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| B | 101 (4.3) | 81 (4.9) | 20 (3.3) | 85 (4.5) | 17 (3.5) | ||

| A and B | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (<0.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Clinical featuref | |||||||

| Recorded fever | 1048 (46.4) | 618 (37.3) | 430 (71.1) | <.001 | 708 (39.9) | 340 (69.5) | <.001 |

| Fast breathing | 1805 (79.8) | 1318 (79.6) | 487 (80.5) | .652 | 1398 (78.9) | 407 (83.2) | .036 |

| Nasal flaring | 569 (25.2) | 167 (10.1) | 402 (66.5) | <.001 | 230 (12.9) | 339 (69.3) | <.001 |

| Vomiting/diarrhea | 392 (17.4) | 264 (15.9) | 128 (21.2) | .004 | 287 (16.2) | 105 (21.5) | .007 |

Abbreviations: H1N1pdm09, 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a Percentages represent factor column totals or the percentage of all SARI cases assessed for the factor; for influenza by year, percentages represent the percentage of the column total within the year.

b SARI with warning signs was determined in 2260 patients with documented clinical severity and hospitalization status.

c For the difference between SARI with warning signs and SARI without warning signs and between hospitalized and nonhospitalized SARI.

d Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was measured in 2143 patients, weight-for-age z score was measured in 2122 patients aged 3–59 months, malaria was measured in 2239 patients, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was measured in 1835 patients recruited during 2011–2013.

e The Fisher exact test used to compare yearly influenza prevalence by clinical severity and hospitalization status.

f Nasal flaring was measured in 2256 participants, vomiting and diarrhea was measured in 2253 participants.

Viruses Detected in Association With SARI

We detected influenza viruses in 266 of 2363 SARI cases (11.3%). When tested for the extended panel of pathogens, influenza A and B viruses (any type) were detected in 201 of 1835 cases (10.9%), rhinoviruses in 358 of 1835 (19.5%), RSV in 220 of 1835 (11.9%), and adenovirus in 162 of 1835 (8.8%). In 542 of 1835 SARI cases (30%), no viral pathogen was detected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Matrix of Monodetection and Codetection of Viral Pathogens by Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction in 1835 Pediatric Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI) Cases in Blantyre, Malawi, 2011–2014a

| Variable | Influenza A(H3N2) | Influenza B | A(H1N1)pdm09 | Influenza C | Bocavirus | Coronavirus 229 | Coronavirus 43 | Coronavirus 63 | Enteroviruses | Adenovirus | Human metapnuemovirus | Parainfluenza virus 1 | Parainfluenza virus 2 | Parainfluenza virus 3 | Parainfluenza virus 4 | Parechoviruses | RSV | Rhinovirus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A(H3N2) | 66 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Influenza B | 0 | 38 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 1 | 1 | 32 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Adenovirus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Bocavirus | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 49 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Coronavirus 229 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Coronavirus 43 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 3 | 38 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Coronavirus 63 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 16 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Enteroviruses | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 13 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Influenza C | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 15 | 77 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Human metapnuemovirus | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 64 | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Parainfluenza virus 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 39 | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Parainfluenza virus 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 14 | … | … | … | … | |

| Parainfluenza virus 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 91 | … | … | … | … |

| Parainfluenza virus 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 24 | … | … | … |

| Parechovirus | 3 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 41 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 6 | … | … |

| RSV | 2 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 155 | … |

| Rhinoviruses | 4 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 31 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 37 | 28 | 16 | 6 | 5 | 20 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 212 |

| Positive test results,a no. (%) |

93 (5.1) |

64 (3.5) |

44 (2.4) |

19 (1.0) |

130 (7.1) |

17 (0.9) |

85 (4.6) |

48 (2.6) |

64 (3.5) |

162 (8.8) |

112 (6.1) |

56 (3.1) |

29 (1.6) |

142 (7.7) |

42 (2.3) |

86 (4.7) |

220 (12.0) |

358 (19.5) |

| Coviral detection, %b | 29.0 | 40.6 | 27.3 | 52.5 | 62.3 | 70.6 | 55.3 | 66.7 | 79.7 | 52.6 | 42.9 | 30.4 | 51.7 | 35.9 | 42.9 | 93.2 | 29.5 | 40.8 |

Abbreviations: H1N1pdm09, 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a Data denote the number of positive test results among all SARI cases tested. Columns do not add up to the total number of positive test results owing to detection of multiple virus in some samples The diagonal of the matrix represents monoinfection.

b Data represent the proportion of viral codetections among SARI cases testing positive for the pathogen (listed at the column heading).

Seasonality of Influenza Virus and RSV

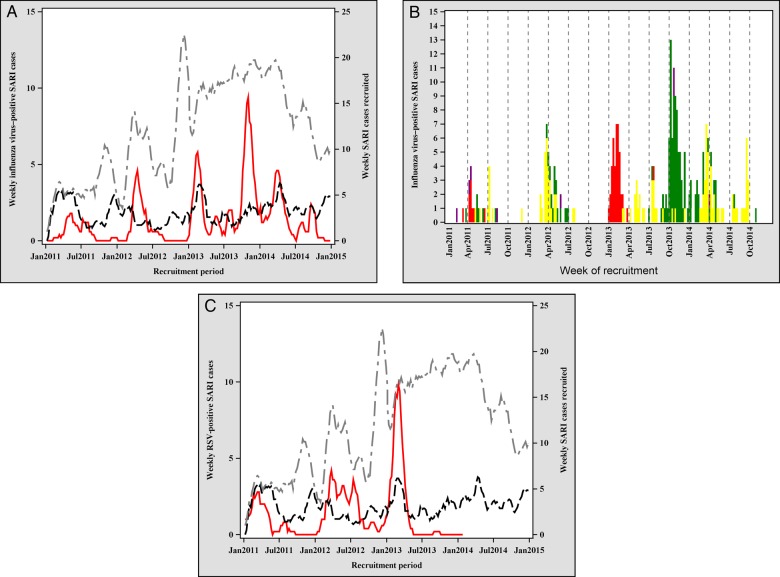

Plots of weekly influenza virus–positive SARI cases suggest both unimodal and bimodal (2 peaks per year) seasonality. Weekly influenza virus–positive SARI cases increased during the rainy season (January–April) in all 4 years of surveillance. A second peak of influenza virus–positive SARI cases, occurring during September–October, was confined to 2013 and 2014 (Figure 1). In multivariable analysis, influenza virus detection during SARI increased in the rainy season (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 3.3; 95% CI, 1.9–5.4) and the cool dry months (May–August; aRR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.6), compared with September–December (Table 3). Influenza virus detection in SARI was significantly higher in the rainy season as compared to the cool dry season (aRR, 1.6, 95% CI, 1.0–2.5). The predominance of influenza virus types varied within and between years. A(H1N1)pdm09 was most prevalent in the first half of 2011 and 2013; influenza A(H3N2) and influenza B viruses were most prevalent in 2012, in the latter half of 2013, and in 2014. In contrast, RSV infection displayed regular seasonality, with peaks in the first half of the rainy season (January–March; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Seasonal plots of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) with warning signs, influenza virus infection, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in pediatric SARI cases, Blantyre, Malawi, 2011–2014. A, The red line denotes influenza virus–positive SARI, the dotted black line denotes SARI with warning signs, and the dotted gray line denotes SARI cases tested. B, The red bars denote 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus, the green bars denotes influenza A(H2N3) virus, the yellow bars denote influenza B virus, and the purple bars denote other influenza virus types. C, The red line denotes RSV-positive SARI, the dotted black line denotes SARI with warning signs, and the dotted gray line denotes SARI cases tested.

Table 3.

Demographic, Seasonal, and Pathogen Factors Associated With Influenza Virus–Positive Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI) in Children, Blantyre, Malawi, 2011–2014

| Factor | Overall | Influenza Virus–Negative No. (%)a |

Influenza Virus–Positive, No. (%) |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRb (95% CI) | P Value | aRRc (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

| Patients, no. | 2239 | 1990 | 249 | … | … | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1187 (53.0) | 1069 (53.7) | 118 (47.4) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 1052 (46.9) | 921 (46.3) | 131 (52.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | .022 | 1.3 (.9–1.8) | .069 |

| Age | |||||||

| 3 mo to <6 mo | 269 (12.0) | 250 (12.6) | 19 (7.6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 6 mo to <12 mo | 576 (25.7) | 536 (26.9) | 40 (16.1) | 0.9 (.5–1.6) | .615 | 0.9 (.4–1.8) | .959 |

| 12 mo to <36 mo | 1071 (47.8) | 943 (47.4) | 128 (51.4) | 1.6 (.9–2.8) | .084 | 1.7 (1.1–2.9) | .046 |

| 36 mo to <60 mo | 241 (10.8) | 198 (9.9) | 43 (17.3) | 3.0 (1.6–5.6) | <.001 | 2.9 (1.6–5.5) | <.001 |

| 5 y to <15 y | 82 (3.7) | 63 (3.2) | 19 (7.6) | 2.9 (1.3–6.3) | <.001 | 2.9 (1.3–6.5) | <.001 |

| Year of recruitment | |||||||

| 2011 | 272 (12.1) | 248 (12.5) | 24 (9.6) | Reference | … | ||

| 2012 (vs 2011) | 489 (21.8) | 459 (23.1) | 30 (12.0) | 0.5 (.1–1.6) | .228 | … | |

| 2013 (vs 2011) | 811 (36.2) | 686 (34.7) | 125 (50.2) | 2.4 (.8–7.5) | .139 | … | |

| 2014 (vs 2011) | 667 (29.8) | 597 (30.0) | 70 (28.1) | 3.2 (1.3–13.3) | .015 | … | |

| Season of recruitment | |||||||

| Sep–Dec | 726 (32.4) | 648 (32.6) | 78 (31.3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Jan–Apr (rainy) | 773 (34.5) | 654 (32.8) | 119 (47.8) | 2.7 (1.6–4.4) | <.001 | 3.3 (1.9–5.4) | <.001 |

| May–Aug (cool dry)d | 740 (33.1) | 688 (34.6) | 52 (20.9) | 1.6 (.9–2.8) | .077 | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | .009 |

| HIV statuse | |||||||

| Negative | 1973 (94.3) | 1747 (94.2) | 226 (95.4) | Reference | … | ||

| Positive | 119 (5.7) | 108 (5.8) | 11 (4.6) | 0.9 (.4–1.7) | .677 | … | |

| Weight-for-age z score <2e | |||||||

| No | 1990 (93.2) | 1766 (93.2) | 224 (92.9) | Reference | … | ||

| Yes | 145 (6.8) | 128 (6.8) | 17 (7.1) | 1.2 (.8–1.6) | .364 | … | |

| Malaria | |||||||

| Negative | 2160 (96.5) | 1913 (96.1) | 247 (99.2) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Positive | 79 (3.5) | 77 (3.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0.2 (.1–.9) | .030 | 0.2 (.0–.8) | .028 |

| Hospitalized | |||||||

| No | 1750 (78.8) | 1549 (77.8) | 201 (80.7) | Reference | … | ||

| Yes | 489 (22.0) | 441 (22.2) | 48 (19.3) | 0.8 (.5–1.1) | .180 | … | |

| Blood oxygen saturation <90% | |||||||

| No | 2291 (93.1) | 2029 (96.8) | 262 (98.1) | Reference | … | ||

| Yes | 72 (6.9) | 67 (3.2) | 5 (1.9) | 0.7 (.3–1.8) | .420 | … | |

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

a Percentages represent column percentages of the column total within each factor.

b Data are from models that included only the variable of interest and patient-level kernel smoothing factors to remove autocorrelation in residuals.

c Data are from a multivariable model developed using backward selection of factors significant at a P value of <.05 and a priori inclusion of age and sex. The model included age, sex, season of recruitment, malaria status, and patient-level kernel smoothing factors to remove autocorrelation in residuals.

d The risk of influenza virus–positive SARI was significantly higher in the rainy season (January–April) as compared to the cool dry season (May–August; aRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.04–2.45).

e Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was measured in 2097 patients, and weight-for-age z score was measured in 2135 patients aged 3–59 months.

Incidence Estimates for SARI and Respiratory Virus–Associated SARI

SARI incidence was 17.5 cases per 10 000 children annually, with the highest incidence in children aged 3–11 months (89.5; 95% CI, 85.8–93.0). Influenza virus–positive SARI incidence was 2.0 cases per 10 000 children annually and was highest in children aged 3–11 months (6.3; 95% CI, 5.3–7.6). The incidence of RSV-positive SARI cases per 10 000 children annually was 4.6 (95% CI, .1–15.8) and was highest in children aged 3–11 months (17.3; 95% CI, 13.7–18.6; Table 4).

Table 4.

Incidence of Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI) in Children Residing in Blantyre City, Malawi, by SARI Type, Age, and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Status

| SARI Group, Age Group | HIV Uninfected | HIV Infected |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence per 10 000 (95% CI) | Incidence per 10 000 (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | |||

| <1 y | 89.5 (85.8–93.0) | 155.3 (127.3–191.1) | 1.7 (1.41–2.14) |

| 12–59 mo | 35.8 (34.9–36.9) | 73.3 (64.7–87.8) | 2.0 (1.82–2.44) |

| 5–9 y | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 16.0 (9.9–24.2) | 12.6 (7.69–19.21) |

| 10–14 y | 0.8 (.7–1.0) | 7.9 (5.5–12.7) | 9.6 (6.52–17.10) |

| SARI with warning signs | |||

| <1 y | 16.5 (15.2–18.0) | 43.1 (29.4–60.7) | 2.6 (1.66–3.61) |

| 12–59 mo | 7.2 (6.7–7.5) | 30.1 (24.4–40.3) | 4.2 (3.34–5.91) |

| 5–9 y | 0.4 (.3–.5) | 9.0 (6.0–15.6) | 24.3 (13.51–51.03) |

| 10–14 y | 0.1 (.1–.2) | 3.3 (1.4–6.7) | 37.7 (11.10–93.21) |

| Hospitalized SARI | |||

| <1 y | 12.3 (11.1–13.8) | 25.9 (14.9–37.2) | 2.1 (1.1–3.0) |

| 12–59 mo | 5.4 (4.9–5.7) | 21.9 (16.7–30.1) | 4.1 (3.0–5.9) |

| 5–9 y | 0.3 (.2–.4) | 6.0 (2.9–11.0) | 21.3 (9.2–48.7) |

| 10–14 y | 0.1 (.0–.2) | 3.3 (.7–5.6) | 37.7 (11.1–109.9) |

| Influenza virus–positive SARI | |||

| <1 y | 6.3 (5.3–7.6) | 6.5 (2.2–15.4) | 1.0 (.40–2.51) |

| 12–59 mo | 4.9 (4.6–5.2) | 3.7 (1.5–8.5) | 0.7 (.30–1.79) |

| 5–9 y | 0.3 (.2–.4) | 6.0 (2.0–11.8) | 21.3 (6.76–42.07) |

| 10–14 y | 0.2 (.2–.4) | 0.9 (.2–2.1) | 8.1 (2.79–19.74) |

| RSV-positive SARI | |||

| <1 y | 17.3 (16.2–19.3) | 17.3 (8.4–29.2) | 0.9 (.5–1.7) |

| 12–59 mo | 3.2 (2.9–3.3) | 4.9 (2.0–9.3) | 1.5 (.6–3.0) |

| 5–9 y | 0.1 (.1–.2) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 0.0 (.0–.0) |

| 10–14 y | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 1.8 (.9–4.6) | …a |

Analyses based on 131 HIV-infected SARI cases, 53 HIV-infected cases of SARI with warning signs, 48 HIV-infected hospitalized SARI cases, 11 HIV-infected influenza virus–positive SARI cases, and 13 HIV-infected RSV-positive SARI cases.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IRR, HIV-associated incidence rate ratio; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a Inestimable.

Risk Factors for SARI With Warning Signs and Virus-Associated SARI

We found that 390 of 1505 patients with SARI (25.9%) had warning signs, among whom 309 of 390 (79.2%) were hospitalized. In multivariable analysis, RSV was the only pathogen associated with SARI with warning signs (aRR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.3–3.0). Nevertheless, 52 of 249 influenza virus–positive SARI cases (20.9%) required hospitalization. A positive HIV test result was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of SARI with warning signs (aRR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.4–3.9; Table 5), as well as an increased incidence of SARI, SARI with warning signs, and influenza virus–positive SARI (Table 4). HIV-associated IRRs rose with increasing age. The HIV-associated IRRs for SARI with warning signs was 2.6 in children aged 3–11 months as compared to 37.7 in children aged 10–14 years. In children aged >5 years, the incidence of hospital-attended influenza virus–positive SARI was at least 8-fold higher in HIV-infected children as compared to HIV-uninfected children. There was no difference in the incidence of RSV-positive SARI between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children.

Table 5.

Demographic, Seasonal, and Pathogen Factors Associated With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARI) With Warning Signs in Children, Blantyre, Malawi, 2011–2013

| Factor | Overall, No. (%)a |

SARI With Warning Signs. No. (%) |

SARI Without Warning Signs, No. (%) |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRb (95% CI) | P Value | aRRc (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

| Patients, no. | 1505 | 1115 | 390 | … | … | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 820 (54.5) | 603 (54.1) | 217 (55.6) | … | … | ||

| Female | 685 (45.5) | 512 (45.9) | 173 (44.4) | 0.83 (.65–1.07) | .157 | 0.80 (.62–1.04) | .091 |

| Age | |||||||

| 3 mo to <6 mo | 171 (11.3) | 137 (12.3) | 34 (8.7) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 6 mo to <12 mo | 390 (25.9) | 294 (26.4) | 96 (24.6) | 1.1 (.7–1.9) | .575 | 1.1 (.7–1.8) | .723 |

| 12 mo to <36 mo | 720 (47.8) | 525 (47.1) | 195 (50.0) | 1.2 (.8–2.0) | .261 | 1.4 (.9–2.2) | .188 |

| 36 mo to <60 mo | 164 (10.9) | 122 (10.9) | 42 (10.8) | 1.2 (.7–2.1) | .553 | 1.2 (.6–2.2) | .524 |

| 5 y to <15 y | 60 (3.9) | 37 (3.3) | 23 (5.9) | 1.5 (.7–3.2) | .300 | 1.5 (.6–3.1) | .322 |

| Year of recruitment | |||||||

| 2011 | 248 (16.5) | 105 (9.4) | 143 (36.7) | … | … | ||

| 2012 (vs 2011) | 464 (30.8) | 361 (32.4) | 103 (26.4) | 0.9 (.4–2.2) | .801 | … | |

| 2013 (vs 2011) | 793 (52.7) | 649 (58.2) | 144 (36.9) | 0.9 (.4–2.3) | .820 | … | |

| Season of recruitment | |||||||

| Sep–Dec | 572 (38.0) | 445 (39.9) | 127 (32.6) | Reference | … | ||

| Jan–April (rain) | 482 (32.0) | 386 (34.6) | 96 (24.6) | 2.9 (1.7–4.8) | <.0001 | 2.4 (1.6–3.8) | <.001 |

| May–August (cool dry) | 451 (29.9) | 284 (25.5) | 167 (42.8) | 0.9 (.6–1.2) | .461 | 0.8 (.59–1.2) | .319 |

| HIV positive | 94 (6.2) | 53 (4.8) | 41 (10.5) | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | .008 | 2.4 (1.4–3.9) | <.001 |

| Mid-upper-arm circumference <11.5, cm | 17 (1.1) | 13 (1.2) | 5 (1.3) | 1.2 (.5–2.8) | .706 | … | |

| Weight for age z score <3 | 73 (4.9) | 52 (4.7) | 21 (5.4) | 1.3 (.8–2.2) | .314 | … | |

| Influenza virus type/subtype | |||||||

| Negative | 1332 (88.5) | 986 (88.4) | 346 (88.7) | Reference | … | ||

| A (not subtyped/mixed) | 6 (0.0) | 4 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 2.1 (.4–12.0) | .413 | … | |

| A(H3N2) | 74 (4.9) | 62 (5.6) | 12 (3.1) | 0.6 (.3–1.3) | .207 | … | |

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 41 (2.7) | 24 (2.2) | 17 (4.4) | 1.9 (.9–4.2) | .642 | … | |

| B | 52 (3.5) | 41 (3.7) | 11 (2.8) | 0.9 (.5–2.1) | .978 | … | |

| Viral codetectiond | 309 | 214 (19.2) | 95 (24.4) | 1.1 (.8–1.3) | .375 | … | |

| PCR positive | |||||||

| Influenza C virus | 17 (1.1) | 14 (1.3) | 3 (0.7) | 0.6 (.2–2.2) | .469 | … | |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 52 (3.5) | 41 (3.7) | 11 (2.8) | 0.8 (.4–1.5) | .427 | … | |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 29 (1.9) | 20 (1.8) | 9 (2.3) | 1.3 (.6–2.9) | .526 | … | |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 127 (8.4) | 95 (8.5) | 32 (8.2) | 0.9 (.6–1.5) | .849 | … | |

| Parainfluenza 4 | 38 (2.5) | 29 (2.6) | 9 (2.3) | 0.9 (.4–1.9) | .751 | … | |

| RSV (A and B) | 164 (10.9) | 94 (8.4) | 70 (17.9) | 2.6 (1.9–3.6) | <.0001 | 1.9 (1.3–3.0) | .002 |

| Adenovirus | 136 (9.0) | 97 (8.7) | 39 (10.0) | 1.2 (.8–1.7) | .659 | … | |

| Enterovirus | 50 (3.3) | 38 (3.4) | 12 (3.1) | 0.9 (.5–1.7) | .754 | … | |

| Rhinovirus | 301 (20.0) | 224 (20.1) | 77 (19.7) | 0.9 (.7–1.4) | .895 | … | |

| Bocavirus | 102 (6.8) | 71 (6.4) | 31 (7.9) | 1.2 (.8–1.9) | .286 | … | |

| Coronavirus 43 | 66 (4.4) | 43 (3.9) | 23 (5.9) | 1.5 (.9–2.6) | .092 | … | |

| Coronavirus 63 | 48 (3.2) | 40 (3.6) | 8 (2.1) | 0.6 (.3–1.2) | .142 | 0.2 (.07–.70) | .010 |

| Coronavirus 229 | 16 (1.1) | 11 (0.9) | 5 (1.3) | 1.3 (.5–3.7) | .625 | … | |

| Human metapneumovirus | 25 (1.7) | 19 (1.7) | 6 (1.5) | 0.9 (.5–1.4) | .529 | … | |

| Parechovirus | 74 (4.9) | 56 (5.0) | 18 (4.6) | 0.9 (.5–1.6) | .634 | … | |

| Malaria positive | 42 (2.8) | 24 (2.2) | 18 (4.6) | 2.2 (1.1–4.6) | .025 | 2.2 (1.1–4.6) | .029 |

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; A(H1N1)pdm09, 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RR, relative risk; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a Percentages represent factor column totals or the percentage of all SARI cases assessed for the factor.

b Data are from models that included only variable of interest and patient-level kernel smoothing factors to remove autocorrelation in residuals.

c Data are from a multivariable model developed using backward selection of factors significant at a P value <.05 and a priori inclusion of age and sex. Model included age, sex, season of recruitment, HIV, RSV, coronavirus 43, malaria status, and patient-level kernel smoothing factors to remove autocorrelation in residuals.

d A total of 362 of 1835 (19.7%) of all SARI cases with multiplex PCR data had viral codetection.

In multivariable analysis controlling for etiology, patients with SARI recruited during the rainy season (January–April) were more than twice as likely to have warning signs, compared with patients enrolled during September–December (aRR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6–3.8; Table 5). Peaks in RSV and influenza virus activity corresponded to peaks in the occurrence of SARI with warning signs (Figure 1). Detection of RSV in cases of SARI warning signs was much higher during the rainy season (39.8%) as compared to other times of year (5.9%).

The aRR for a positive results of an influenza virus test in patients with SARI increased with older age and rainy season of recruitment (Table 3). After adjustment for age, sex, and HIV status, rainy season recruitment was significantly associated with SARI with warning signs in influenza virus–positive patients with SARI (aRR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.37–8.53; analysis not shown). In adjusted analysis, A(H1N1)pdm09 was associated with double the risk of SARI with warning signs, compared with other influenza virus subtypes (aRR, 2.10; 95% CI, .98–4.53; analysis not shown).

Coviral Infection, Viral Clustering, and Clinical Severity in SARI

Detection of ≥2 viral pathogens by multiplex PCR occurred in 362 of 1835 SARI cases (19.7%). Viral codetection was highest in SARI cases positive for coronavirus 229 (70.6%) and enterovirus (79.7%). Viral codetection was least common in SARI cases testing positive for A(H1N1)pdm09 (27.3%), influenza A(H3N2) virus (29.0%), and RSV (29.5%) (Table 2).

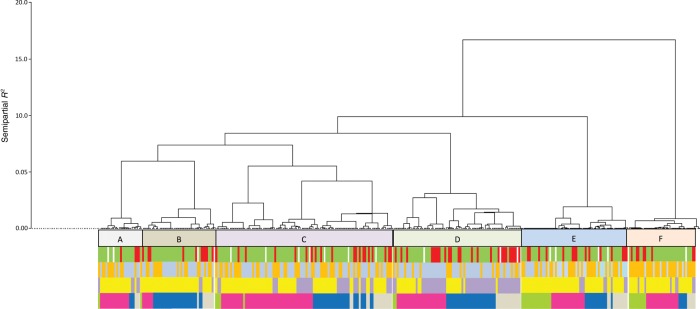

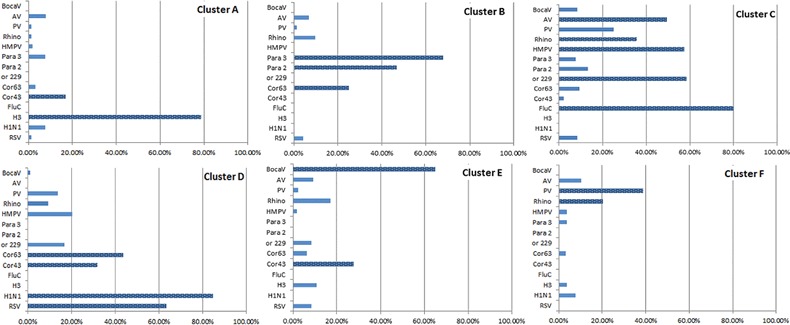

Viral codetection per se was not associated with warning signs in SARI (Table 5). We used discrete hierarchical cluster analysis based on similarity of viral pathogens detected by multiplex PCR assay in SARI cases to explore whether particular groupings of viruses were associated with warning signs, host factors, or seasonal factors. We identified 6 clusters, which accounted for 48.3% of the total variation in viral pathogen test results in children with viral codetection. Cluster size ranged from 23 to 96 members; smaller clusters had fewer viral pathogens and lower within-cluster heterogeneity. Clusters were distinguishable by the type of viral pathogens detected. For example, 80% of influenza A(H3N2) viruses detected were found in cluster A; >65% of bocaviruses detected were found in cluster E (Appendix 3).

Cluster membership was significantly associated with clinical and temporal factors (Figure 2). Among children with viral codetection, membership in cluster D (characterized by A(H1N1)pdm09, RSV, and coronaviruses 43 and 63) was associated with nearly double the risk of SARI with warning signs (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.2–3.5; analysis not shown), compared with other clusters. In cluster D, 47 of 70 members (67%) had RSV or A(H1N1)pdm09 infection (Appendix 3); 11.4% of members had RSV and A(H1N1)pdm09 coinfection, accounting for all such coinfections in patients with SARI. Rainy season recruitment was significantly associated with cluster D, while dry season recruitment was significantly associated with cluster B (characterized by parainfluenza viruses 2 and 3). Clusters were also significantly associated with temporal peaks in viral pathogen activity. For example, 65% of cluster A members were recruited during a peak in influenza A(H3N2) virus activity that occurred from September to December in 2013 (Figures 1 and 2), compared with 13.3% of other children with viral codetection. Cluster membership was not associated with host factors (age, sex, HIV status, and underweight).

Figure 2.

Dendrogram of coviral clusters. Six coviral clusters (A–F) were identified in 362 pediatric SARI cases, in whom >2 viral pathogens were detected in the nasopharynx. Each severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) case is a member of only one cluster; clusters membership is based on similarity of viral pathogens detected. As shown here, characteristics such as SARI severity, number of viruses detected per child, and particular season and year of recruitment are more common in some clusters than others. Green bars denote SARI without warning signs, red bars denote SARI with warning signs, bluish-gray bars denote detection of <3 viruses detected, orange bars denote detection of ≥3 viruses, lavender bars denote recruitment in the rainy season, yellow bars denote recruited outside of the rainy season, gray bars denote recruitment in 2011, blue bars denote recruitment in 2012, pink bars denote recruitment in 2013, and light green bars denote recruitment in 2014.

DISCUSSION

Hospital-attended SARI was common in this urban sub-Saharan African setting, particularly in infants aged 3–11 months, in whom the incidence was 91.7 cases per 10 000 children annually. Similar to studies from other settings, influenza viruses and RSV were important SARI-associated pathogens [5–8, 22, 23], with prevalence rates of 11% and 12%, respectively. As elsewhere, HIV infection increased the risk of SARI and the presence of warning signs in SARI cases [24–26]. Among older children, HIV infection greatly increased the risk of influenza virus–positive SARI, consistent with data from South Africa [25].

Viral coinfection occurred in almost 20% of SARI cases, highlighting its potential impact in the development or clinical worsening of SARI [27]. Although viral codetection per se was not associated with clinical severity or season, we found 1 viral cluster, characterized by a high proportion of RSV and A(H1N1)pdm09 infection, which was significantly associated with clinical warning signs and rainy season recruitment. Cluster members coinfected with RSV and A(H1N1)pdm09 had a higher rate of warning signs, but the number of coinfected individuals (within the cluster and the entire sample) was too small to formally test for interaction. It is unclear therefore whether clinical severity in this cluster resulted from biological interaction of pathogens, additive risks from each pathogen, or other underlying factors. Clusters clearly mapped to peaks and troughs in individual pathogen activity. We suggest that this viral clustering, which was associated temporal dynamics of pathogen activity, may have arisen from complex virus-virus and host-virus pathogen interactions.

Clinical severity in SARI demonstrated seasonal peaks, coinciding with rainy season peaks in RSV activity. RSV was detected in 40% of SARI cases with warning signs recruited during the rainy season, compared with 6% recruited at other times of the year. Thus, RSV may drive rainy season increases in clinical severity in pediatric SARI in our setting, consistent with studies elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa [28, 29]. Nevertheless, the rainy season remained independently associated with an increased risk of warning signs in SARI in multivariable analysis controlling for RSV, HIV, and other viral pathogens. Therefore, the observed rainy season excess of clinical severity in SARI is in part attributable to unmeasured factors. We speculate that these factors include other intervening illnesses and seasonal malnutrition (in Malawi, the rainy season coincides with the so-called lean season after harvest [30]). However, we cannot exclude seasonal differences in healthcare utilization.

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. We did not recruit children aged <3 months, in whom the frequency of SARI-related deaths is known to be elevated [31]. We were unable to determine the role of bacterial pathogens in SARI, as we lacked laboratory data and systematic radiological data to identify probable infection in the context of a very high prevalence of bacterial carriage. Our estimates of SARI incidence by HIV strata were based on Mozambican pediatric HIV prevalence rates because we lacked data from Malawi. Nevertheless, Malawi and Mozambique have similar rates of antenatal HIV prevalence [12, 32, 33] and similarly high rates of HIV-infected pregnant women accessing antiretroviral treatment [34]. We did not assess the impact of HIV exposure on SARI risk in HIV-uninfected children. HIV exposure was associated with higher SARI incidence and greater SARI severity in HIV-uninfected South African children [35].

In conclusion, SARI is common in this setting of high HIV prevalence, where influenza viruses, rhinoviruses, and RSV were the most prevalent viruses detected. HIV greatly increased the risk of influenza virus–associated SARI in children, and therefore yearly influenza vaccination should be considered in routine pediatric HIV clinical care. Influenza vaccination in HIV-infected children is safe, but it has low efficacy (<20%) and may only be immunogenic in older children and adolescents with virological suppression [36–38]. Viral coinfection was common, with 1 coviral cluster associated with clinical severity in SARI cases. In this context, there is considerable potential for the use of multiplex respiratory virus assays in tandem with cluster analysis to reveal multiple-pathogen–associated outbreaks and disease burden. This approach may expose the potential for synergistic effects of vaccine strategies that disrupt viral clusters. Vaccine probe studies to assess the impact of viral coinfection on clinical severity could clarify complex pathogen and host interrelationships and reveal the true burden of disease.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. This work was supported by with the CDC through a cooperative agreement (grant 5U01CK000146-04).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

APPENDIX 1

Description of implementation of FTF multiplex assay FTD rRT-PCR assay was used in combination with the AgPath one-step qRT-PCR reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Carlsad, California, USA). Viral pathogens included in the FTD kit were: influenza A, B and C viruses, coronaviruses OC43, NL63, HKU1 and 229E, parainfluenza viruses 1-4; RSV A and B; enteroviruses; human metapneumovirus; rhinoviruses; adenovirus; bocavirus; and parechoviruses. Samples with a Ct-value <40 were recorded as positive.

APPENDIX 2

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of data analyses. Abbreviations: FTD, FTD respiratory pathogens 33 kit; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SARI, severe acute respiratory infection.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of data analyses. Abbreviations: FTD, FTD respiratory pathogens 33 kit; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SARI, severe acute respiratory infection.

APPENDIX 3

Viral pathogens detected in 6 clusters identified by discrete hierarchical cluster analysis of pediatric severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) cases with viral codetection. Abbreviations: AV, adenovirus; BocaV, bocavirus; Cor43, coronavirus 43; Cor63, coronavirus 63; Cor229, coronavirus 229; FluC, influenza C virus; H1N1, 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus; H3, influenza A(H2N3) virus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; Para 3, parainfluenza virus 1; Para 2, parainfluenza virus 2; PV, parechovirus; Rhino, Rhinovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

References

- 1. Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L et al. . Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013; 381:1405–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nair H, Simoes EA, Rudan I et al. . Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2013; 381:1380–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simusika P, Bateman AC, Theo A et al. . Identification of viral and bacterial pathogens from hospitalized children with severe acute respiratory illness in Lusaka, Zambia, 2011–2012: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Homaira N, Luby SP, Petri WA et al. . Incidence of respiratory virus-associated pneumonia in urban poor young children of Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009–2011. PLoS One 2012; 7:e32056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feikin DR, Njenga MK, Bigogo G et al. . Viral and bacterial causes of severe acute respiratory illness among children aged less than 5 years in a high malaria prevalence area of western Kenya, 2007–2010. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:e14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lagare A, Mainassara HB, Issaka B, Sidiki A, Tempia S. Viral and bacterial etiology of severe acute respiratory illness among children < 5 years of age without influenza in Niger. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mainassara HB, Lagare A, Tempia S et al. . Influenza sentinel surveillance among patients with influenza-like-illness and severe acute respiratory illness within the framework of the national reference laboratory, Niger, 2009–2013. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0133178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breiman RF, Cosmas L, Njenga M et al. . Severe acute respiratory infection in children in a densely populated urban slum in Kenya, 2007–2011. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Self WH, Williams DJ, Zhu Y et al. . Respiratory viral detection in children and adults: comparing asymptomatic controls and patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:584–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berkley JA, Munywoki P, Ngama M et al. . Viral etiology of severe pneumonia among Kenyan infants and children. JAMA 2010; 303:2051–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glennie SJ, Nyirenda M, Williams NA, Heyderman RS. Do multiple concurrent infections in African children cause irreversible immunological damage? Immunology 2012; 135:125–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NSO and ICF Macro. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NSO and ICF Macro, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mihigo R, Torrealba CV, Coninx K et al. . 2009 Pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1 vaccination in Africa--successes and challenges. J Infect Dis 2012; 206(suppl 1):S22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Health GoMMo. HIV and Syphilis Sero–Survey and National HIV Prevalence and AIDS Estimates Report for 2010. Lilongwe: National Aids Commission, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. SanJoaquin MA, Allain TJ, Molyneux ME et al. . Surveillance Programme of IN-patients and Epidemiology (SPINE): implementation of an electronic data collection tool within a large hospital in Malawi. PLoS Med 2013; 10:e1001400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Copan. Copan Universal Transport Medium [package insert]. Brescia, Italy: Copan Italia, 2006.

- 17. World Health Organization (WHO). Rapid HIV tests: guidelines for use in HIV testing and counselling services in resource-constrained settings. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2004:48. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malawi National Statistics Office. 2008 Malawi Population and Housing Census. Zomba, Malawi: Malawi National Statistics Office, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Instituto Nacional de Saúde (INS), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), e ICF Macro. 2010. Inquérito Nacional de Prevalência, Riscos Comportamentais e Informação sobre o HIV e SIDA em Moçambique 2009. Calverton, Maryland, EUA: INS, INE e ICF Macro. [Google Scholar]

- 20. ICF International. HIV prevalence estimates from the demographic and health surveys. Calverton, MD: ICF International, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gower JC, Legendre P. Metric and euclidean properties of dissimilarity coefficients. J Classif 1986; 3:5–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bigogo GM, Breiman RF, Feikin DR et al. . Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus infection in rural and urban Kenya. J Infect Dis 2013; 208(suppl 3):S207–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katz MA, Muthoka P, Emukule GO et al. . Results from the first six years of national sentinel surveillance for influenza in Kenya, July 2007-June 2013. PLoS One 2014; 9:e98615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madhi SA, Schoub B, Simmank K, Blackburn N, Klugman KP. Increased burden of respiratory viral associated severe lower respiratory tract infections in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus type-1. J Pediatr 2000; 137:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen C, Moyes J, Tempia S et al. . Severe influenza-associated respiratory infection in high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2009–2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:1766–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen C, Walaza S, Moyes J et al. . Epidemiology of severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) among adults and children aged >/=5 years in a high HIV-prevalence setting, 2009–2012. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0117716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paranhos-Baccala G, Komurian-Pradel F, Richard N, Vernet G, Lina B, Floret D. Mixed respiratory virus infections. J Clin Virol 2008; 43:407–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tempia S, Walaza S, Viboud C et al. . Mortality associated with seasonal and pandemic influenza and respiratory syncytial virus among children <5 years of age in a high HIV prevalence setting--South Africa, 1998–2009. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:1241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD et al. . Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:1545–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Food Program. Malawi: current issues and what the World Food Programme is doing. https://www.wfp.org/countries/malawi Accessed 8 January 2016.

- 31. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015; 385:430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manda S, Masenyetse L, Cai B, Meyer R. Mapping HIV prevalence using population and antenatal sentinel-based HIV surveys: a multi-stage approach. Popul Health Metr 2015; 13:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Young PW, Mahomed M, Horth RZ, Shiraishi RW, Jani IV. Routine data from prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) HIV testing not yet ready for HIV surveillance in Mozambique: a retrospective analysis of matched test results. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kieffer MP, Mattingly M, Giphart A et al. . Lessons learned from early implementation of option B+: the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation experience in 11 African countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67(suppl 4):S188–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen C, Moyes J, Tempia S et al. . Epidemiology of acute lower respiratory tract infection in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatrics 2016; 137:pii:e20153272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Madhi SA, Dittmer S, Kuwanda L et al. . Efficacy and immunogenicity of influenza vaccine in HIV-infected children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. AIDS 2013; 27:369–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levin MJ, Song LY, Fenton T et al. . Shedding of live vaccine virus, comparative safety, and influenza-specific antibody responses after administration of live attenuated and inactivated trivalent influenza vaccines to HIV-infected children. Vaccine 2008; 26:4210–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leahy TR, Goode M, Lynam P, Gavin PJ, Butler KM. HIV virological suppression influences response to the AS03-adjuvanted monovalent pandemic influenza A H1N1 vaccine in HIV-infected children. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2014; 8:360–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.