Abstract

Background:

Stress classically describes a destructive notion that can have a bearing on one's physical and mental health. It may also add to an increased propensity to periodontal disease.

Aim:

To investigate the association between psychological stress and serum cortisol levels in patients with chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

Forty subjects were recruited from the outpatient department at the Department of Periodontics, from a college in Mangalore, divided into two groups, i.e., twenty as healthy controls and twenty were stressed subjects with chronic periodontitis. The clinical examination included the assessment of probing pocket depth, clinical attachment level and oral hygiene index-simplified. Serum cortisol levels were estimated biochemically using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method and the estimation of psychological stress was done by a questionnaire.

Results:

Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation was used to review the collected data. Independent sample t-test was used for comparison and correlation was evaluation using Pearson's correlation test. As per our observation, high serum cortisol levels and psychological stress are positively linked with chronic periodontitis establishing a risk profile showing a significant correlation (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Routine serum cortisol assessment may be a reasonable and a valuable investigative indicator to rule out stress in periodontitis patients as it should be considered as an imperative risk factor for periodontal disease.

Key words: Chronic periodontitis, periodontal disease, psychological stress, serum cortisol

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis is an infectious disease caused by Gram-negative bacteria which leads to the inflammation of the tissues supporting the teeth, continous attachment loss, and bone loss.[1] It is usually considered to be a gradually progressing disease. Although with the existence of systemic or environmental factors that may alter the host response to plaque build-ups, such as diabetes, smoking or stress, disease development may become more violent.

Periodontal disease is multifactorial with multifarious relations between bacteria and host responses which is often customized by behavioral factors. Stress is also a contributing feature in periodontal disease. Moreover, the word stress has an accurate physiological definition, i.e., it is a state of physiological and psychological strain caused by an adverse stimuli, physical, mental or emotional, internal or external that tends to perturb the functioning of an organism and which an organism naturally tries to circumvent. Thus, “stress” can be described as a process with both physiological and psychological components.[2]

The role of stress in periodontitis has a conceivable pathological concept. This is because stress can cause behavior variation and increase at-risk behaviors such as smoking, alcohol abuse, and improper oral hygiene due to reduced compliance with dental care as well as some immunosuppressive effects.[3]

Cellular immune response is downregulated by psychological stress in three different ways:

The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis[4]

The peripheral release of neuropeptides

The sympathetic nervous system via the release of adrenaline and noradrenaline.[3]

Cortisol is a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal gland. It is the key hormone in stress and fight or flight response. It is a well-established stress biomarker and is controlled by adrenocorticotropic hormone from the pituitary gland. Its levels can be affected by physical stress, emotional stress, and illness.[1] In case of high level of stress, serum cortisol value is bound to increase, thus it is a reliable indicator in patients undergoing stressful events in life.

With this background, the goal of this study was to assess and compare the association between psychological stress and serum cortisol levels of healthy individuals and patients with chronic periodontitis.

Objectives of the study

The objectives of this study were:

To estimate serum cortisol levels of healthy individuals

To estimate serum cortisol levels and oral hygiene status of stressed subjects with chronic periodontitis

To compare and correlate the association between psychological stress and serum cortisol levels of healthy individuals and patients with chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty subjects were recruited from the routine outpatient department at the Department of Periodontics, Mangalore. The nature and rationale of the study was explained to all the participants, and consent was obtained for the same. The study group was divided into two groups:

Group I – Twenty subjects with healthy periodontium

Group II – Twenty stressed subjects with chronic periodontitis.

Method of collection of data

The sample size was calculated with expected parameter (cortisol levels) estimate based on minimum 20% ratio of differences between control and test group. The minimum sample size thus required was required to be approximately forty within a 95% confidence and power of 80% with level of significance as P > 0.05.

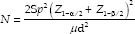

Sample size was calculated using the following formula:

α – Level of significance; Sp2 – Pooled variance; 1 – β – Power; μd – Clinical significant difference.

Criteria for selection

Inclusion criteria

Both male and female subjects within the age group of 25–50 years

Subjects with a minimum complement of twenty teeth

Systemically healthy subjects

Subjects with healthy periodontium (Group I), i.e., no attachment loss and probing depth (PD) of (<3 mm)

Subjects diagnosed with chronic periodontitis (Group II) as per International Workshop for Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions,[5] i.e., the involvement of (>30% sites) with moderate to severe clinical attachment loss (CAL) (>3 mm) was measured with William's periodontal probe

Subjects who have scored twenty points or higher (Group II) on the Perceived Stress Scale by Cohen et al.,[6] as this score indicates high stress in a subject.

Exclusion criteria

Patients on corticosteroid therapy

Patients on immunosuppressive drugs

Patients who are under antibiotic treatment and have undergone periodontal treatment 6 months before examination

Trauma or bleeding in the oral cavity not related to periodontitis

Pregnancy or lactation

Patients on tranquilizers, sedatives, and antidepressants

Patients who smoke and consume alcohol.

Screening examination

Patients were asked about the basic demographic details including age, family history of periodontal disease, smoking, and frequency of brushing and flossing were recorded. Participants also indicated if they ignore oral hygiene during the periods of stress or depression

Evaluation of stress by the subject on five-point scale was recorded, and stress level was evaluated for each patient using Perceived Stress Scale by Cohen et al. 1983.[6]

Clinical procedure: Periodontal parameters

Mean probing pocket depth: The pocket depth was measured using Williams's graduated periodontal probe at six sites, i.e., distobuccal, midbuccal, mesiobuccal, distolingual, midlingual, and mesiolingual of each tooth. All six measurements were added and divided by the number of sites examined, i.e., six to obtain the mean PD for an individual tooth

Mean clinical attachment level: Clinical attachment level was measured on six surfaces per tooth, i.e., distobuccal, midbuccal, mesiobuccal, distolingual, midlingual, and mesiolingual

Oral hygiene index-simplified (OHI-S)[7] was recorded for each subject.

Method of collection of sample

Collection of blood sample: About 3–5 ml of blood was collected by venipuncture, from the median cubital vein between 9 and 11 am from the subjects after 20 min of rest to the subject

Estimation of cortisol in serum: Blood was centrifuged and then, serum cortisol level was evaluated using Cortisol ELISA Kit.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation was utilized to condense the collected data.

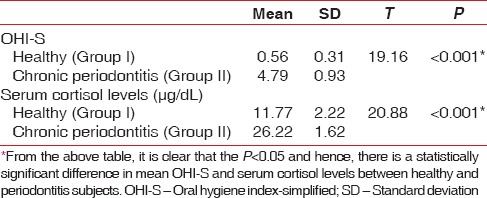

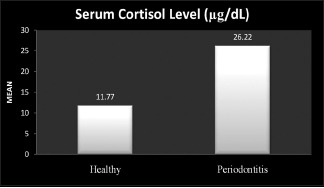

Independent sample t-test was used to compare the difference in mean of OHI-S and serum cortisol levels between Group I and II [Table 1].

Table 1.

Results of independent sample t-test

To study the correlation between serum cortisol levels and PD, CAL, Pearson's correlation coefficient was obtained (R value) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Correlation between serum cortisol level and periodontal parameters

If P < 0.05, then it was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study included forty subjects divided into two groups, Group I constituted healthy individuals, whereas Group II included stressed subjects with chronic periodontitis.

OHI-S and serum cortisol levels of all these subjects were calculated which were compared using independent sample t-test. Results are described in [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

Investigations promoting the recognition of risk factors are acquiring essence for management and prevention for periodontitis as it is a multifactorial disease. It is recommended that stress, depression, and unsuccessful coping may add to the progression of periodontitis.[8]

The periodontal breakdown is promoted, as persistent stress may tend to have a total destructive effect on the immunological response of body leading to an disparity between host response and pathogens.[9]

Numerous clinical studies have investigated the probable relationship between psychological stress and periodontitis and have recommended that stress may play a role in the advancement of periodontal disease.[10,11,12,13]

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the association between psychological stress and serum cortisol levels in patients with chronic periodontitis.

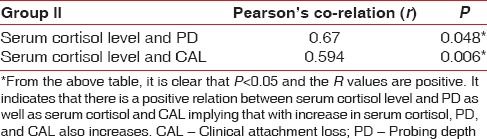

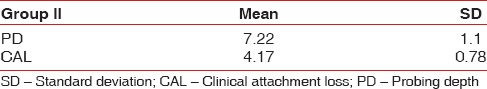

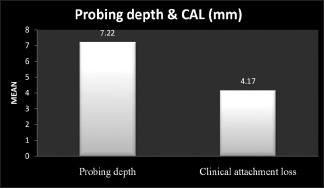

The results of this study specify increased mean serum cortisol levels in Group II as compared to Group I [Graph 1 and Table 1]. This indicates that serum cortisol is increased in stressed individuals with chronic periodontitis. These results are in agreement with other similar studies where a noteworthy correlation was found between psychological stress, serum cortisol levels, and periodontal clinical parameters.[14,15,16] This can be explained as stress-induced response transfers to the HPA axis and promotes the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone from the pituitary gland and glucocorticoid hormones from the adrenal cortex.[17] When cortisol is released into the circulation, it leads to unsolicited effects throughout the body such as modification of certain growth factor levels, elevation of blood glucose levels, and containment of the inflammatory response.[18] Table 3 depicts mean probing depth and clinical attachment loss in Group II subjects.

Graph 1.

Comparison of mean serum cortisol level in health and periodontitis group

Table 3.

Mean probing depth and clinical attachment loss (mm) (Group II)

In the inter-group comparison, assessing the correlation between serum cortisol level and periodontal parameters, i.e. CAL and PD [Table 2], there was a statistically significant (P < 0.05) and positive correlation between psychological stress and patients suffering from chronic periodontitis. This can be explained by the biologic model suggesting that increased level of steroids results in decreased resistance to infection by suppressing IgA, causing immunosuppression due to which initial colonization of periodontal pathogens is favored thereby leading to an increase in the severity of disease.[19]

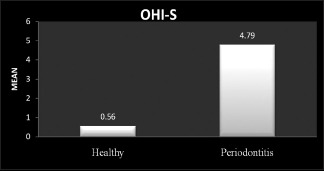

Furthermore, on comparing the mean oral hygiene score of Group I with II [Graph 2 and Table 1], there was a noteworthy difference between the two, indicating that Group II patients had poor oral hygiene status (depicted in Graph 3). This is in accordance with the behavioral model signifying that psychosocial stress may impact behavioral changes affecting health behaviors (i.e. smoking, poor compliance, and poor oral hygiene). Moreover, stress leads to overeating, especially high fat diets which increase cortisol release.[19] These results are in accordance with other similar studies where it was affirmed that psychosocial stress may induce neglect from oral hygiene and also severe attachment loss and increased PD.[8,20,21,22,23] Contrasting views have been reported in other studies by Monteiro da Silva et al., Castro et al., Solis et al., where no correlation was found between stress and established periodontitis.[24,25,26]

Graph 2.

Comparison of oral hygiene index-simplified score

Graph 3.

Mean probing depth and clinical attachment loss in Group II

Within the scope of this study, it can be concluded that high serum cortisol levels and psychological stress are positively associated with chronic periodontitis establishing a risk profile.

Limitations

Stress among the women population was not satisfactorily determined as this study had few female participants.

Other manifestations such as recurrent aphthous ulcers, bruxism, lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis, and deleterious habits such as smoking and tobacco chewing can also be linked with stress along with periodontal disease, but such patients were barred from the study.

Lastly, this study included subjects only from low socio-economic background, hence there could be a reasonable likelihood of bias.

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that there is an affirmative relation between stress, serum cortisol, and chronic periodontitis within the precincts of this study. Hence, for evaluating the risk of chronic periodontitis, assessing patients for stress is an essential factor. However, further research is needed including larger sample size and taking other factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and financial strain into consideration to verify the impact of stress on periodontal disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Financial assistance for this study was provided by NITTE University, Mangalore.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rai B, Kaur J, Anand SC, Jacobs R. Salivary stress markers, stress, and periodontitis: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2011;82:287–92. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyapati L, Wang HL. The role of stress in periodontal disease and wound healing. Periodontol 2000. 2007;44:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haririan H, Bertl K, Laky M, Rausch WD, Böttcher M, Matejka M, et al. Salivary and serum chromogranin A and α-amylase in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1314–21. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahendra L, Austin RD, Kumar SS, Mahendra J, Felix AJ. Relationship between psychological stress, serum cortisol, expression of MMP-1 and chronic periodontitis in male police personnel. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2012;3:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.1999 International International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. Papers. Oak Brook, Illinois, October 30-November 2, 1999. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4(i):1–112. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S, Kessler RC, Underwood Gordon L. A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosania AE, Low KG, McCormick CM, Rosania DA. Stress, depression, cortisol, and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80:260–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green LW, Tryon WW, Marks B, Huryn J. Periodontal disease as a function of life events stress. J Human Stress. 1986;12:32–6. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1986.9936764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page RC. The pathobiology of periodontal diseases may affect systemic diseases: Inversion of a paradigm. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:108–20. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elter JR, Beck JD, Slade GD, Offenbacher S. Etiologic models for incident periodontal attachment loss in older adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:113–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vered Y, Soskolne V, Zini A, Livny A, Sgan-Cohen HD. Psychological distress and social support are determinants of changing oral health status among an immigrant population from Ethiopia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jalaleddin H, Kakaei S, Hamissi H. Psychological stress and periodontal disease. Pak Oral Dent J. 2010;30:464–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishisaka A, Ansai T, Soh I, Inenaga K, Awano S, Yoshida A, et al. Association of cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate levels in serum with periodontal status in older Japanese adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:853–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, Bandeira DR, Bozzetti MC. Stress, cortisol, and periodontitis in a population aged 50 years and over. J Dent Res. 2006;85:324–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolic M, Bailer J, Staehle HJ, Eickholz P. Psychosocial factors as risk indicators of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1134–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai KK, Nayak SU. Stressing the stress in periodontal disease. J Pharm Biomed Sci. 2013;26:345–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller DB, O'Callaghan JP. Neuroendocrine aspects of the response to stress. Metabolism. 2002;51(6 Suppl 1):5–10. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genco RJ, Ho AW, Kopman J, Grossi SG, Dunford RG, Tedesco LA. Models to evaluate the role of stress in periodontal disease. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:288–302. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deinzer R, Hilpert D, Bach K, Schawacht M, Herforth A. Effects of academic stress on oral hygiene – A potential link between stress and plaque-associated disease? J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:459–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028005459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman R, Goss S. Stress measures as predictors of periodontal disease – A preliminary communication. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:176–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng SK, Keung Leung W. A community study on the relationship between stress, coping, affective dispositions and periodontal attachment loss. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:252–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peruzzo DC, Benatti BB, Ambrosano GM, Nogueira-Filho GR, Sallum EA, Casati MZ, et al. A systematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1491–504. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monteiro da Silva AM, Newman HN, Oakley DA, O'Leary R. Psychosocial factors, dental plaque levels and smoking in periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:517–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro GD, Oppermann RV, Haas AN, Winter R, Alchieri JC. Association between psychosocial factors and periodontitis: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:109–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solis AC, Lotufo RF, Pannuti CM, Brunheiro EC, Marques AH, Lotufo-Neto F. Association of periodontal disease to anxiety and depression symptoms, and psychosocial stress factors. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:633–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]