Abstract

Background:

Periodontal deterioration has been reported to be associated with systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus, respiratory disease, liver cirrhosis, bacterial pneumonia, nutritional deficiencies, and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Aim:

The present study assessed the periodontal disease among patients with systemic conditions such as diabetes, CVD, and respiratory disease.

Materials and Methods:

The study population consisted of 220 patients each of CVD, respiratory disease, and diabetes mellitus, making a total of 660 patients in the systemic disease group. A control group of 340 subjects were also included in the study for comparison purpose. The periodontal status of the patients with these confirmed medical conditions was assessed using the community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITNs) index.

Results:

The prevalence of CPITN code 4 was found to be greater among the patients with respiratory disease whereas the mean number of sextants with score 4 was found to be greater among the patients with diabetes mellitus and CVD. The treatment need 0 was found to be more among the controls (1.18%) whereas the treatment need 1, 2, and 3 were more among the patients with respiratory disease (100%, 97.73%, and 54.8%), diabetes mellitus (100%, 100% and 46.4%), and CVD (100%, 97.73%, and 38.1%), in comparison to the controls (6.18%).

Conclusion:

From the findings of the present study, it can be concluded that diabetes mellitus, CVD, and respiratory disease are associated with a higher severity of periodontal disease.

Key words: Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, oral health, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis, a chronic infectious and inflammatory disease of the periodontal tissue and supporting structures, has recently attracted interest as a potential risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and type 2 diabetes, and also for its association with other medical conditions such as adverse pregnancy outcomes, respiratory disease, kidney disease, and certain cancers.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] There has been a shift from viewing periodontal disease as a localized oral health problem to discovering connections between periodontal disease and other systemic diseases. This arena of oral systemic connections is known as periodontal medicine.[8]

Several studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of periodontitis and the extent of attachment loss increase considerably with age, but some of the studies have shown that most (47%) of the patients with periodontal disease were suffering from a systemic disorder.[9,10]

Periodontal disease is one of the major oral health problems encountered among patients with diabetes mellitus.[11] It has been observed that patients with uncontrolled diabetes have an increased risk for periodontal diseases. One of the studies has also shown a two-way relationship between periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus.[12]

Periodontal infection may adversely influence the glycemic control among patients with diabetes and decrease insulin-mediated glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, resulting in a poor glycemic control. Moreover, induced production of pro-inflammatory mediators in periodontal disease also mediates insulin resistance and reduces insulin action.[13] It is conceivable that unresolved periodontal disease could also increase blood sugar, contribute to increased period of time when the body functions with high blood sugar, and make it harder for patients to control their blood sugar, putting poorly controlled patients with diabetes at a higher risk of the complications of the condition.[13]

Clinical studies have found that people with periodontal diseases are almost twice as likely to suffer from coronary artery disease as those without periodontal diseases.[14,15,16] People diagnosed with acute cerebrovascular ischemia, particularly nonhemorrhagic stroke, were found to be more likely to have a periodontal infection.[17] A recent study has shown that periodontal disease might be a significant independent risk factor for the development of peripheral vascular disease.[18]

It has come to the focus that one of the most common route of infections for bacterial pneumonia is aspiration of oropharyngeal contents.[19] Oral bacteria have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this disease, and in this regard, dental plaque (DP) might be an important reservoir for these potential pathogens.[20] Alveolar bone loss (ABL) due to periodontal disease has been found to be an independent predictor of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[21]

As such, not much studies have attempted to compare the periodontal diseases' occurrence among patients with diabetes mellitus, CVD, and respiratory disease. Hence, the present study was undertaken to determine the possible associations of diabetes mellitus, CVD, and respiratory disease with periodontal disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted to assess the periodontal status among patients with CVD, respiratory disease, and diabetes mellitus, and compare with the healthy individuals. The data were obtained from the tertiary care government hospitals of the Bengaluru city.

Ethical clearance

Before conducting the study, the required permission for conducting the study was obtained from the concerned hospital authorities. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Government Dental College and Research Institute, Bengaluru. A written informed consent to carry out the study was obtained from the participants/attendees before carrying out the examination which was in accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki.

Reliability and validity of the data

Training and calibration of the examiner

The clinical examination of the subjects was carried out by a single-trained examiner. The examiner was trained under the guidance of the staff members at the Department of Public Health Dentistry, Government Dental College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, having previous experience in conducting such surveys to limit the intra-examiner variability. The training was continued till the examiner obtained consistent observations. The training was done on the patients reporting as outpatients to the Department of Public Health Dentistry, Government Dental College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, such that they represented a wide range of oral findings.

The intra-examiner variability was checked by performing repeat examination on 10% of the randomly selected patients during the survey, and the intraexaminer kappa co-efficient values were calculated to be more than 0.82.

Selection of the study population

The study population consisted of adults between 30 and 79 years of age with at least twenty teeth in the oral cavity and/or eligible for the recording of community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITNs) index. The patients with the confirmed diagnosis of CVD, respiratory disease, and diabetes mellitus as confirmed by the medical records of the patients were included in the systemic disease/conditions group.

The participants selected as controls were relatives/family members of these patients who were free from any systemic disease/conditions matched for age, gender, and other confounding factors.

Inclusion criteria

The patients who were included in the study were as follows:

Two hundred and twenty patients each with a confirmed diagnosis of CVD (coronary artery disease), respiratory disease (tuberculosis of lungs, chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma, and pneumonia), and noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes mellitus) as per the hospital records

The control group included the healthy subjects without any systemic disease/conditions

Almost equal number of male and female participants were included to avoid gender bias

Matching of the subjects in the systemic disease/conditions and control group was done on the baseline characteristics such as age, gender, and oral hygiene habits.

Exclusion criteria

The patients who were excluded from the study were as follows:

Patients with a history of tobacco and alcohol use were excluded from the study

Patients who were severely ill and not suitable for oral examination

Patients in whom proper medical history could not be recorded and/or medical records to ascertain the medical condition of the patient could not be obtained.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated on the basis of the results of the pilot study which was done on fifty cases each of CVD, respiratory disease, and noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

By the results of the pilot study, the study population consisted of 220 patients each with a confirmed diagnosis of CVD, respiratory disease, and diabetes mellitus. A control group of 340 patients were also included in the study for comparison purpose. A total of 1000 patients formed the final sample size to be recorded for the study. The participants who were part of the pilot study were not included again in the main study to avoid bias.

Method of data collection

The data were collected by a single investigator using a standardized pro forma which consisted of two parts. The information was recorded through an interview designed in English and Kannada, the local language, and clinical examination was done to record the periodontal index using the CPITN index.

The first part included the general information regarding the patient's demographic profile, oral hygiene practices, and personal habits (such as tobacco, alcohol, or any other abusive habits). All relevant information regarding the age, oral hygiene aids used (finger, stick, toothbrush, tooth paste, tooth powder, tongue cleaner, mouth washes, and interdental brushes), and frequency of tooth brushing (once and twice daily) was recorded.

The second part included clinical examination, which was carried out using the CPITN index[22] for assessing the periodontal status and recording the periodontal treatment needs as well. The CPITN index was recorded using the WHO CPI probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA).

Data collection

Screening of the patients was carried out at the tertiary care government hospitals of the Bengaluru city. The study population was selected who satisfied the inclusion and the exclusion criteria. The medical condition of the patients under the study was confirmed from the medical records of the hospital which included the clinical history and biochemical confirmation. There was a strict selection of the study patients, and patients with only one of the medical conditions (as mentioned in the inclusion criteria) were included in each study group. The controls were chosen either from the attendants who accompanied these patients or attendants of the other patients.

For selection of the study population, a total of 1245 patients with systemic diseases and 503 healthy controls were screened and matched with respect to baseline characteristics. The study sample consisted of 220 patients each of the chronic medical conditions under study and 340 healthy control subjects.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16, IBM Inc., Chicago, USA and Epi Info version 6.0, CDC, USA. The Chi-square test was used to compare the categorical variables among the groups and the analysis of variance test was used to compare between the mean CPITN scores when comparison was made between more than two groups. P < 0.05 was taken as significant (confidence interval: 95%).

RESULTS

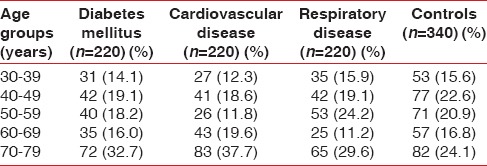

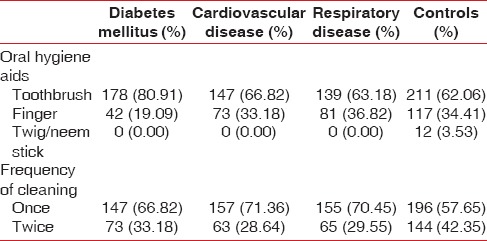

The comparison of the prevalence and mean sextants affected per person with CPITN codes was made among patients with different systemic disease/conditions under study and controls. The age range of the study population was 30–79 years and mean age of the patients with diabetes mellitus was 50.06 ± 16.63 years, CVD was 51.69 ± 17.11 years, respiratory disease was 52.91 ± 15.81 years, and controls was 50.29 ± 16.91 years. The age and gender profile of the study population is shown in Table 1. There was no difference in the oral hygiene habits among the study population [Table 2].

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the study population

Table 2.

Oral hygiene habits among the study population

The mean number of missing teeth among patients with diabetes mellitus was 3.87 ± 3.67, CVD was 4.27 ± 4.47, respiratory disease was 6.08 ± 5.27, and controls was 1.36 ± 2.64. The predominant reason for missing teeth among patients with diabetes mellitus, CVD, and respiratory disease was periodontal disease (85.0%, 80.6%, and 80.3%, respectively) whereas among controls, it was dental caries (77.5%).

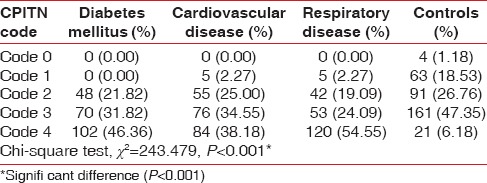

The prevalence of CPITN code 1 was found to be significantly (P < 0.05) more among controls (18.53%) in comparison to patients with diabetes mellitus (0%), respiratory disease (2.27%), and CVD (2.27%), code 2 was found to be more among patients with CVD (25.00%) and controls (26.76%) in comparison to diabetes mellitus patients (21.82%), code 3 was found to be more among controls (47.35%) whereas the CPITN code 4 was found to be more among the patients with CVD (38.18%), respiratory disease (54.4%), and diabetes mellitus (46.4%), in comparison to controls (6.18%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Prevalence of community periodontal index of treatment needs codes (highest community periodontal index of treatment needs score per subject) among the study population

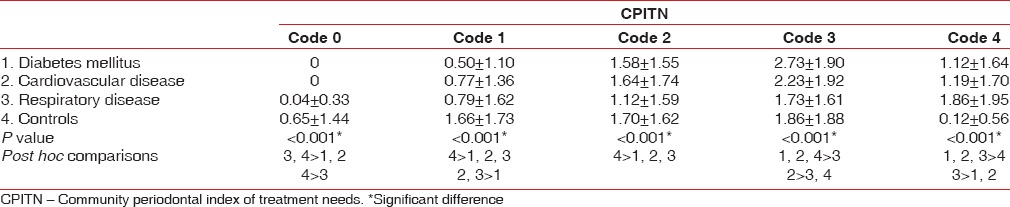

The mean number of sextants affected with CPITN code 0 and 1 was significantly (P < 0.05) greater among controls (0.65 ± 1.44 and 1.66 ± 1.73, respectively). The CPITN code 2 was significantly (P < 0.05) greater among the patients with respiratory disease (1.12 ± 1.59), diabetes mellitus (1.58 ± 1.55), and CVD (1.64 ± 1.74). The CPITN code 3 was significantly (P < 0.05) greater among the patients with diabetes mellitus (2.73 ± 1.90) and CVD (2.23 ± 1.92). The CPITN code 4 was significantly (P < 0.05) greater among the patients with respiratory disease (1.86 ± 1.95), diabetes mellitus (1.12 ± 1.64), and CVD (1.19 ± 1.70), in comparison to the controls (0.12 ± 0.56) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Mean number of sextants affected per person according to community periodontal index of treatment needs score among the study population

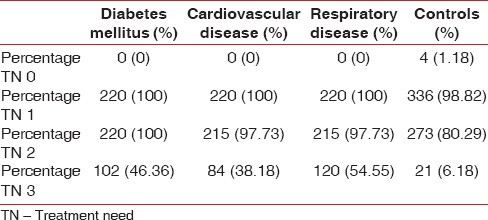

The treatment needs were calculated as per the calculation suggested by the WHO for the CPITN index.[22] The treatment need 3 was calculated as the number of subjects with treatment need 1 plus treatment need 2 and similarly for treatment need 2. The treatment need 0 was found to be more among the controls (1.18%) whereas the treatment need 1, 2, and 3 were more among the patients with respiratory disease (100%, 97.73%, and 54.8%), diabetes mellitus (100%, 100%, and 46.4%), and CVD (100%, 97.73%, and 38.1%), in comparison to the controls (6.18%) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Distribution of treatment need codes among study population

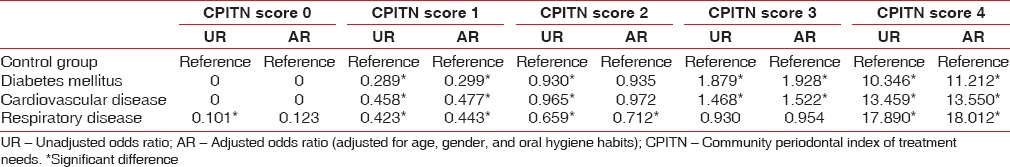

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for age, gender, and oral hygiene habits) was calculated using the binary logistic regression analysis. Regression analysis had shown that odds of having the CPITN score 3 and 4 was found to be significantly greater among the patients with respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, and CVD, in comparison to the control group [Table 6].

Table 6.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis for comparing the CPITN scores among control group, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and respiratory disease patients

DISCUSSION

The mean number of missing teeth among patients with diabetes mellitus was 3.87 ± 3.67, CVD was 4.27 ± 4.47, and respiratory disease was 6.08 ± 5.27, as compared to the controls (1.36 ± 2.64). Bacic et al.[23] also reported similar findings with a mean number of extracted teeth significantly higher among the diabetic group (12.3) than control group (9.7). In a study by Emingil et al.,[24] the mean number of missing teeth among the patients with acute myocardial infarction was 8.88 ± 7.09 and chronic coronary heart disease (CHD) was 10.3 ± 7.3. Similar findings were also reported in a study by Castillo et al.,[25] in which, dental loss was reported to be more severe among patients with hypertension (P < 0.001), diabetes (P = 0.05), coronary artery disease (P = 0.04), and calcium channel blocker use (P = 0.04). All these studies report a higher number of missing teeth among patients with systemic disease.

In the present study, the prevalence of CPITN codes 0, 1, 2, and 3 was significantly (P < 0.05) more among the controls as compared to the patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 whereas CPITN code 4 was more among diabetes mellitus type 2 patients (46.36%). This was found to be almost similar to a study conducted by Sandholm et al.[26] (codes 1, 2, 3, and 4 were higher in diabetes mellitus type 2 group) and Ogunbodede et al.[27] (CPITN code 4 in diabetics [20%] was found to be higher than among the controls [14.8%]).

The mean CPITN codes 3 and 4 (2.73 ± 1.9 and 1.12 ± 1.64, respectively) were significantly (P < 0.05) more among the patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. This was similar to the study by Bacic et al.[23] (the CPITN code 4 was found in an average of 1.3 sextants in the diabetic and 0.3 sextants in the control group subjects).

The prevalence of CPITN codes and mean CPITN codes was found to be more among patients with diabetes, indicating that the periodontal disease was found to be more severe among diabetic patients as compared with nondiabetic healthy patients. This was in accordance with various studies by Emrich et al.,[12] Tervenon and Oliver,[28] Cerda et al.,[29] Morton et al.,[30] Novaes et al.,[31] Soskolne,[32] Grossi and Genco,[13] Almas et al.,[33] Campus et al.,[34] Mealey and Oates,[35] and Apoorva et al.[36]

In the present study, the prevalence of CPITN codes 0, 1, 2, and 3 was more among controls whereas CPITN code 4 was found to be significantly (P < 0.05) higher among patients with CVD (38.18%). This was quite similar to a study by Katz et al.,[37] in which, CPITN code 4 was higher among CHD patients (22.5%) in comparison to the controls (17.2%).

The association between the periodontal disease and CVD has been studied by different authors in different ways such as in terms of clinical parameters such as probing depth, clinical attachment loss (CAL), bleeding on probing, and radiograph parameters such as ABL and bone loss. All these studies have shown a positive association between periodontal disease and CVD. This was also established in the studies by Ruquet et al.,[38] Geismar et al.,[39] Geerts et al.,[40] Malthaner et al.,[41] Geerts et al.,[40] Sim et al.,[42] Alman et al.,[43] Amoian et al.,[44] and Hashemipour et al.[45]

Sharma and Shamsuddin[46] compared 100 hospitalized patients with respiratory disease and 100 age-, sex-, and race-matched outpatient controls (systemically healthy patients) and found that patients with respiratory disease had significantly greater poor periodontal health (OHI and PI), gingival inflammation, deeper pockets, and CAL as compared to controls. These findings were similar to the present study, in which, CPITN score 4 was found to be more among patients with respiratory disease.

The study by El-Solh et al.[47] also showed that aerobic respiratory pathogens colonizing DP may be an important reservoir for hospital-acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. The findings similar to the present study of association between respiratory and periodontal disease have also been documented by Azarpazhooh and Leake,[48] Pace and McCullough,[49] and Scannapieco et al.[50]

In the present study, the treatment needs 1, 2, and 3 were found to be more among the patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 (100%, 100%, and 46.4%) as compared to the controls (98.8%, 80.2%, and 6.2%), which was almost similar to the study of Bacic et al.[26] (treatment need 1 and 2 was 100% among both diabetes mellitus type 2 and control group and treatment need 3 was needed by 50.9% of the diabetics in comparison to 17.9% of the control subjects).

However, in a retrospective study by Marjanovic and Buhlin,[51] it was found that patients with periodontitis presented with more systemic diseases, such as CVD and diabetes mellitus than control patients. However, no association was found between periodontitis and respiratory diseases. Periodontitis is reversible in patients with well-controlled diabetes and the outcome of its treatment in patients with diabetes is similar to that in nondiabetics.[52] As such, no such literature could be found showing the comparison of periodontal status among the different disease conditions to make relevant comparisons.

The present study has certain limitations such as the use of CPITN index for recording the periodontal index, as this index was used for being easier to record in the field conditions. One of the major limitations of the study is the cross-sectional study design of the study making it difficult to infer-causal relationship. Thus warranting the need for an analytical study design to establish a causal relationship between the systemic disease and periodontal disease. The biochemical level of severity of disease was not recorded as that required for laboratory investigations.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, all these findings in the present study suggest the relationship between systemic health and periodontal disease, which is in line with most of the studies that have revealed periodontal diseases to be more pronounced among the patients with systemic disease/conditions. Periodontal disease is a very prevalent oral condition and is responsible for a considerable portion of tooth loss, especially among the elderly population. The CPITN codes were found to be more among the patients with systemic disease/conditions than the controls.

The relationship between the periodontal and systemic disease is a two-way relationship and can have common risk factors. Hence, by following a common risk factor approach,[53] these diseases as well as the periodontal disease among these patients can be managed. The key concept underlying the integrated common risk approach is that promoting general health by controlling a small number of risk factors might have a major impact on a large number of diseases at a lower cost, greater efficiency, and effectiveness than disease-specific approach.

Hence, it is desirable that health-care professionals and dentists promote self-care for systemic health conditions as well as oral health education for the management of both systemic health conditions and periodontal health, especially among patients with a long duration of systemic health conditions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the help of the statisticians Mr. Tejasvi and Mr. Jagannatha for their valuable support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahekar AA, Singh S, Saha S, Molnar J, Arora R. The prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis: A meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2007;154:830–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grau AJ, Becher H, Ziegler CM, Lichy C, Buggle F, Kaiser C, et al. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:496–501. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110789.20526.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khader YS, Dauod AS, El-Qaderi SS, Alkafajei A, Batayha WQ. Periodontal status of diabetics compared with nondiabetics: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications. 2006;20:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saremi A, Nelson RG, Tulloch-Reid M, Hanson RL, Sievers ML, Taylor GW, et al. Periodontal disease and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:27–32. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shultis WA, Weil EJ, Looker HC, Curtis JM, Shlossman M, Genco RJ, et al. Effect of periodontitis on overt nephropathy and end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:306–11. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett ML. The oral-systemic disease connection. An update for the practicing dentist. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:5S–6S. doi: 10.1080/01944360608976719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobetsis YA, Barros SP, Offenbacher S. Exploring the relationship between periodontal disease and pregnancy complications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:7S–13S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendrick EJ. Poor dental and periodontal health are known to complicate infection control and compromise outcomes in kidney transplants. Rev Endocrinol. 2007:26–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandler HC, Stahl SS. Prevalence of periodontal disease in a hospitalized population. J Dent Res. 1960;39:439–49. doi: 10.1177/00220345600390030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgiou TO, Marshall RI, Bartold PM. Prevalence of systemic diseases in Brisbane general and periodontal practice patients. Aust Dent J. 2004;49:177–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakhshandeh S, Murtomaa H, Mofid R, Vehkalahti MM, Suomalainen K. Periodontal treatment needs of diabetic adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:53–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emrich LJ, Shlossman M, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1991;62:123–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: A two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:51–61. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornman KS, Crane A, Wang HY, di Giovine FS, Newman MG, Pirk FW, et al. The interleukin-1 genotype as a severity factor in adult periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scannapieco FA. Position paper of The American Academy of Periodontology: Periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for systemic diseases. J Periodontol. 1998;69:841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeStefano F, Anda RF, Kahn HS, Williamson DF, Russell CM. Dental disease and risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. BMJ. 1993;306:688–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6879.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, Dorn JP, Falkner KL, Sempos CT. Periodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: The first national health and nutrition examination survey and its follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2749–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendez MV, Scott T, LaMorte W, Vokonas P, Menzoian JO, Garcia R. An association between periodontal disease and peripheral vascular disease. Am J Surg. 1998;176:153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonten MJ, Gaillard CA, van Tiel FH, Smeets HG, van der Geest S, Stobberingh EE. The stomach is not a source for colonization of the upper respiratory tract and pneumonia in ICU patients. Chest. 1994;105:878–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.3.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limeback H. Implications of oral infections on systemic diseases in the institutionalized elderly with a special focus on pneumonia. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:262–75. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes C, Sparrow D, Cohen M, Vokonas PS, Garcia RI. The association between alveolar bone loss and pulmonary function: The VA Dental Longitudinal Study. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:257–61. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN) Int Dent J. 1982;32:281–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacic M, Plancak D, Granic M. CPITN assessment of periodontal disease in diabetic patients. J Periodontol. 1988;59:816–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.12.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emingil G, Buduneli E, Aliyev A, Akilli A, Atilla G. Association between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1882–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.12.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castillo R, Fields A, Qureshi G, Salciccioli L, Kassotis J, Lazar JM. Relationship between aortic atherosclerosis and dental loss in an inner-city population. Angiology. 2009;60:346–50. doi: 10.1177/0003319708319783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandholm L, Swanljung O, Rytömaa I, Kaprio EA, Mäenpää J. Periodontal status of Finnish adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:617–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogunbodede EO, Fatusi OA, Akintomide A, Kolawole K, Ajayi A. Oral health status in a population of Nigerian diabetics. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:75–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tervonen T, Oliver RC. Long-term control of diabetes mellitus and periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:431–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerda J, Vázquez de la Torre C, Malacara JM, Nava LE. Periodontal disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM).The effect of age and time since diagnosis. J Periodontol. 1994;65:991–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morton AA, Williams RW, Watts TL. Initial study of periodontal status in non-insulin-dependent diabetics in Mauritius. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;121:532–6. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)00001-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novaes AB, Jr, Gutierrez FG, Novaes AB. Periodontal disease progression in type II non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients (NIDDM). Part I – Probing pocket depth and clinical attachment. Braz Dent J. 1996;7:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soskolne WA. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of periodontal diseases in diabetics. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:3–12. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almas K, Al-Qahtani M, Al-Yami M, Khan N. The relationship between periodontal disease and blood glucose level among type II diabetic patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2001;2:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campus G, Salem A, Uzzau S, Baldoni E, Tonolo G. Diabetes and periodontal disease: A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:418–25. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mealey BL, Oates TW. AAP-commissioned review-diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1289–303. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Apoorva SM, Sridhar N, Suchetha A. Prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus (non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) patients in Bangalore city: An epidemiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:25–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz J, Chaushu G, Sharabi Y. On the association between hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular disease and severe periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:865–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028009865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruquet M, Maille G, Tavitian P, Tardivo D, Hüe O, Bonfil JJ. Alveolar bone loss and ageing: Possible association with coronary heart diseases and/or severe vascular diseases. Gerodontology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/ger.12168. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geismar K, Stoltze K, Sigurd B, Gyntelberg F, Holmstrup P. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1547–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geerts SO, Legrand V, Charpentier J, Albert A, Rompen EH. Further evidence of the association between periodontal conditions and coronary artery disease. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1274–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.9.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malthaner SC, Moore S, Mills M, Saad R, Sabatini R, Takacs V, et al. Investigation of the association between angiographically defined coronary artery disease and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1169–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.10.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sim SJ, Kim HD, Moon JY, Zavras AI, Zdanowicz J, Jang SJ, et al. Periodontitis and the risk for non-fatal stroke in Korean adults. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1652–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alman AC, Johnson LR, Calverley DC, Grunwald GK, Lezotte DC, Harwood JE, et al. Loss of alveolar bone due to periodontal disease exhibits a threshold on the association with coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1304–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amoian B, Maboudi A, Abbasi V. A periodontal health assessment of hospitalized patients with myocardial infarction. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2:234–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashemipour MA, Afshar AJ, Borna R, Seddighi B, Motamedi A. Gingivitis and periodontitis as a risk factor for stroke: A case-control study in the Iranian population. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2013;10:613–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma N, Shamsuddin H. Association between respiratory disease in hospitalized patients and periodontal disease: A cross-sectional study. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1155–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, Okada M, Zambon J, Aquilina A, et al. Colonization of dental plaques: A reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital-acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. Chest. 2004;126:1575–82. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1465–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pace CC, McCullough GH. The association between oral microorgansims and aspiration pneumonia in the institutionalized elderly: Review and recommendations. Dysphagia. 2010;25:307–22. doi: 10.1007/s00455-010-9298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:54–69. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marjanovic M, Buhlin K. Periodontal and systemic diseases among Swedish dental school patients – A retrospective register study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11:49–55. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christgau M, Palitzsch KD, Schmalz G, Kreiner U, Frenzel S. Healing response to non-surgical periodontal therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus: Clinical, microbiological, and immunologic results. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:112–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: A rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:399–406. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]