Abstract

Introduction:

The sense of coherence (SOC) has been suggested to be highly applicable concept in the public health area because a strong SOC is stated to decrease the likelihood of perceiving the social environment as stressful. This reduces the susceptibility to the health-damaging effect of chronic stress by lowering the likelihood of repeated negative emotions to stress perception.

Materials and Methods:

The demographic data and general information of subjects' oral health behaviors such as frequency of cleaning teeth, aids used to clean teeth, and dental attendance were recorded in the self-administered questionnaire. The SOC-related data were obtained using the short version of Antonovsky's SOC scale. The periodontal status was recorded based on the modified World Health Organization 1997 pro forma.

Results:

The total of 780 respondents comprising 269 (34.5%) males and 511 (65.5%) females participated in the study. A significant difference was noted among the subjects for socioeconomic status based on gender (P = 0.000). The healthy periodontal status (community periodontal index [CPI] code 0) was observed for 67 (24.9%) males and 118 (23.1%) females. The overall SOC showed statistically negative correlation with socioeconomic status scale (r = −0.287). The CPI and loss of attachment (periodontal status) were significantly and negatively correlated with SOC.

Conclusion:

The present study concluded that a high level of SOC was associated with good oral health behaviors, periodontal status, and socioeconomic status.

Key words: Oral health, oral health behaviors, periodontal status, sense of coherence

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, health has been regarded as the “absence of disease.” However, over the decades, it has been recognized that the social, psychosocial, economic, and cultural factors influence health. This holistic concept implies that all sectors of the society influence health and emphasizes on promotion and protection of health.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined “health” as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Hence, measuring health should not be confined to the use of exclusively clinical normative indicators.[2]

Health being multidimensional is under the control of individual as well as is dependent on the environmental components (physical, biological, psychosocial), and further interaction of these factors may be health promoting or deleterious. In the recent years, the behavioral and psychosocial determinants of health have been recognized to play a pivotal role in causing health disorders. Hence, public health research has increased its focus on social determinants of health and this has led to the emergence of theoretical approaches stressing the social context and its interaction with biological and psychological factors.[3]

One key factor which governs the health in today's life is stress. Stress has been defined as a “physiological response to situations or issues that may not affect the person's attitude or body positively.”[4] When stress occurs, most of the people are affected by poor or negative habits that may impact their health.

Many theoretical models have been proposed to promote oral health and to explain oral diseases. Most of these models are based either on biomedical factors or on psychosocial factors.[5] One such conceptual model focusing on both dimensions is the salutogenic theory and its core construct namely sense of coherence (SOC).[6] The SOC concept was proposed by Aaron Antonovsky and was first published in the year 1983,[7] which explains the relationship between health and stress. SOC has been defined as “a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that:

The stimuli deriving from one's internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable, and explicable

The resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by these stimuli

These demands are challenges, worthy of investment, and engagement.”

The above three are referred to as the three components of SOC; they are comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness.[8] “Comprehensibility” is the ability of people to understand what is happening around them; “manageability” is the extent to which they feel capable of managing the situation; and “meaningfulness” is the ability to find meaning in the situation.[3]

SOC has been suggested to be highly applicable concept in the public health area because a strong SOC is stated to decrease the likelihood of perceiving the social environment as stressful.[9] This reduces the susceptibility to the health-damaging effect of chronic stress by lowering the likelihood of repeated negative emotions to stress perception.[6]

A strong evidence of SOC is being related to health diseases and health-related behaviors.[10,11,12] Furthermore, association of SOC to oral health was first reported by Freire et al. in the year 2001 among 15-year-old children in Middle West Brazil; their study concluded that the SOC is a psychosocial determinant of adolescent's oral health-related behavior affecting their pattern of dental attendance.[7]

However, correlation of SOC with oral health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and periodontal status among Indians has not been reported yet. With this background, our research goal was to evaluate the effect of SOC; hence, an attempt has been made in the present study to correlate the SOC with oral health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and periodontal status among 35–44 years adults visiting Panineeya Mahavidyalaya Institute of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Hyderabad.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Before the commencement, the study protocol was submitted for approval, and the ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Panineeya Mahavidyalaya Institute of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Hyderabad (PMVIDS/PHD/0013/2011). Written informed consent was obtained from all the study patients before clinical examination.

Adults aged 35–44 years visiting the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology of Panineeya Mahavidyalaya Institute of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Hyderabad, for the first time were included in the study. The study was conducted for 3 months from January 2013 to March 2013.

A pilot study was conducted for 1 week, and the SOC questionnaire was pretested and validated. The pilot study assessments were utilized for sample size estimation, planning of the main study, and also to finalize the survey pro forma. Based on the prevalence of clinical loss of attachment (LOA) scores, the sample size (n) was determined.

Subjects were included in the study based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

All adults aged 35–44 years visiting Panineeya Mahavidyalaya Institute of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Hyderabad

Those visiting the dental hospital for the first time

Patients willing to participate and who gave the written consent.

Exclusion criteria

Physically and mentally challenged individuals

Individuals using antibiotics for more than 3 months

Individuals unable to tolerate oral examination.

The following information was gathered from the study subjects:

Demographic information (age, sex, and marital status)

Socioeconomic status using Kuppuswamy scale[13]

Oral health behaviors (type of cleaning, toothbrush, method of cleaning, materials used, and visit to dentist)

Perceived oral health status (good/poor).

The SOC was measured using short version of the SOC questionnaire by Aaron Antonovsky comprising 13-item measuring the following components:[3]

Comprehensibility (Q2, Q5, Q6, Q8, Q9, Q10, and Q11)

Manageability (Q3 and Q13)

Meaningfulness (Q1, Q4, Q7, and Q12).

Each item was scored on a seven-point Likert scale with two opposite anchoring phrases (1 = very often, 7 = very seldom) and the questions Q1, Q2, Q3, Q7, and Q10 were reversed scored. The SOC score is an aggregation of all the scores with a range from 13 to 91, with higher scores reflecting high levels of SOC. The questionnaire was used in both English and Telugu (vernacular) languages.

The clinical examination of all the patients was done by a single pretrained, precalibrated examiner to limit intraexaminer variability. The periodontal status was assessed using community periodontal index (CPI) and Loss Of Attachment (LOA) based on the codes and criteria according to the WHO proforma 1997.[14]

Statistical analysis

Statistical package for social sciences software (Version 18.0, Statistical Data2009 SPSS, Inc., an IBM company, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used to analyze the statistical data.

Statistical test

Mann–Whitney U-test and unpaired t-test were utilized to determine the association between mean scores of SOC with oral health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and periodontal status. Karl Pearson's correlation coefficient test was employed to find the correlation of SOC with oral health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and periodontal status. Multiple group comparison was done using analysis of variance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 780 respondents comprising 269 (34.5%) males and 511 (65.5%) females participated in the study. A majority of the patients belonged to the age group of 35–39 years, with a mean age of 38.5 ± 2.8 years. Most of the study subjects were married (763, 97.8%).

According to Kuppuswamy socioeconomic status, more number of patients belonged to upper lower class (IV) (263, 33.7%), followed by upper middle class (II) (223, 28.6%) and lower middle class (III) (177, 22.7%). On the other hand, very few patients belonged to upper class (I) (90, 11.5%) and lower class (V) (27, 3.5%). A significant difference was noted among the patients for socioeconomic status based on gender (P = 0.000).

All the study patients used toothbrush (780, 100%) for teeth cleaning, with majority (387, 49.6%) using medium type of toothbrush. When the materials used for brushing was taken into account, around 747 (95.8%) of the patients preferred using toothpaste and only 33 (4.2%) patients used tooth powder.

Horizontal method of tooth cleaning was most common (461, 59.1%), followed by vertical method (168, 21.5%) and circular method (151, 19.3%). A good number of the patients 619 (79.4%) brushed once a day and 161 (20.6%) patients had the habit of brushing their teeth twice daily. A majority of patients, i.e., 623 (79.8%), preferred brushing before meals, 146 (18.7%) patients brushed before and after meals, and just 11 (1.4%) patients brushed after meals.

The total of 688 (88.2%) patients used other oral hygiene aids such as dental floss and mouth rinses. There were 566 (72.6%) patients who previously visited the dentist, of which 415 (53.2%) were females and 151 (19.3%) were males. Around 447 (57.3%) of the study patients perceived their oral health as poor and 333 (42.3%) study patients perceived as good oral health.

When comparison of study patients for oral health behaviors was done based on gender, statistically significant difference was obtained for materials used for cleaning (P = 0.000), type of toothbrush used (P = 0.010), and visit to the dentist (P = 0.000).

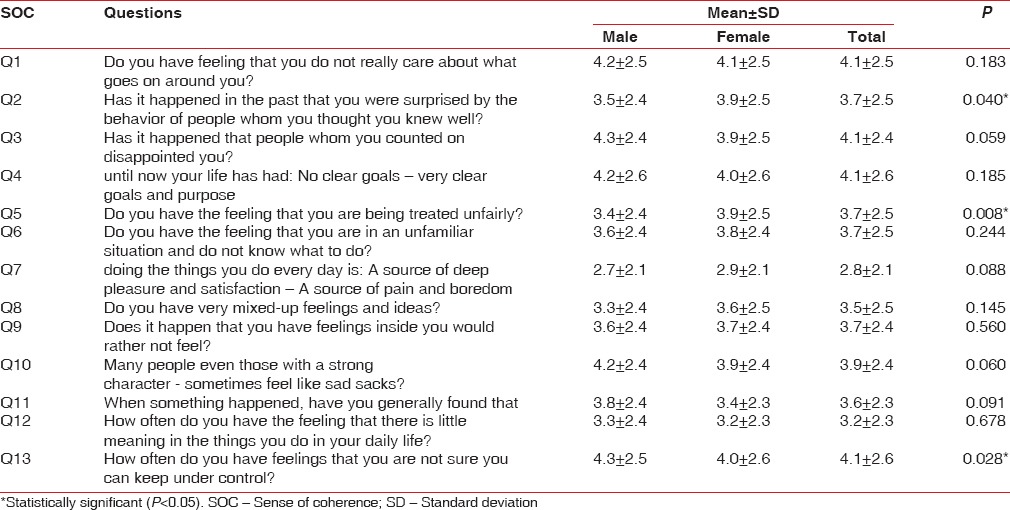

The SOC scores for this group of study population ranged from 20 to 78, with an overall mean score of 48.2 ± 10.4. When the mean SOC scores were compared, females showed statistically significant difference for Q2 – “Has it happened in the past that you were surprised by the behavior of people whom you thought you knew well?” (3.9 ± 2.5, P = 0.040) and Q5 – “Do you have the feeling that you are being treated unfairly?” (3.9 ± 2.5, P = 0.008). On the contrary, the mean score for the question Q13 – “How often do you have feelings that you are not sure you can keep under control?” was significantly high in males (4.3 ± 2.5, P = 0.028) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of mean sense of coherence score for each question based on gender

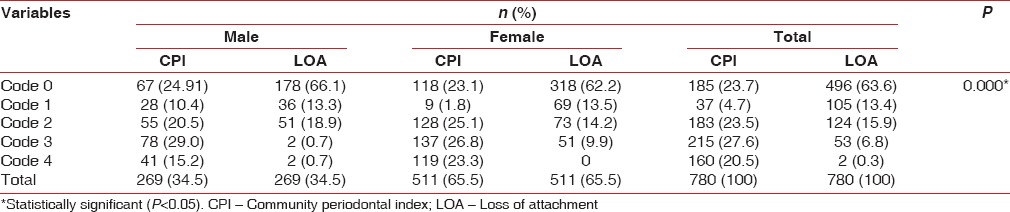

Healthy periodontal status (CPI code 0) was observed for 67 (24.9%) males and 118 (23.1%) females. The code 1 of CPI, i.e., bleeding on probing, was more common among male patients (28, 10.4%), whereas calculus (code 2, 25.1%), shallow pocket (code 3, 26.8%), and deep pocket (code 4, 23.3%) were mostly seen in females. A statistically significant gender difference was noted among the patients for the scores of CPI (P = 0.000). While considering the distribution for LOA, the results showed that 318 (62.2%) females and 178 (66.1%) males had code 0, i.e. normal 0–3 mm LOA. The LOA of 4–5 mm (code 1) was seen in 69 (13.5%) females and 36 (13.3%) males. Furthermore, majority of female patients (73, 14.2%) had cementoenamel junction (CEJ) between the upper limit of the black band at 8.5 mm ring (code 2) and 51 (9.9%) male patients had CEJ between 8.5 and 11.5 mm ring (code 3). Only 2 (0.7%) male patients had code 4, i.e. CEJ beyond 11.5 mm ring, but none of the female subjects have CEJ beyond 11.5 mm ring. LOA scores were statistically significant based on gender (P = 0.000) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of community periodontal index and loss of attachment scores based on gender

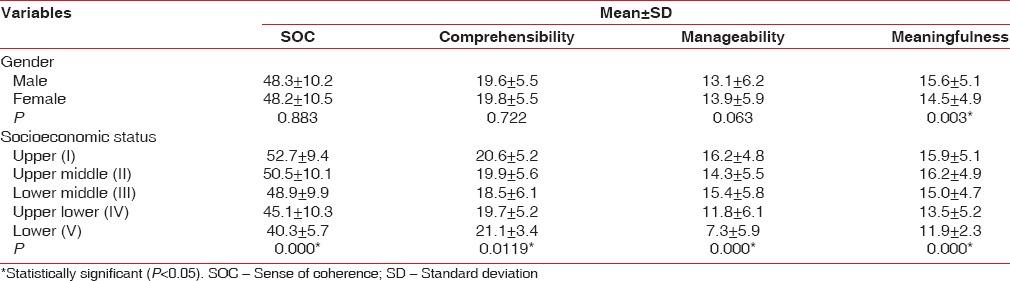

The overall mean SOC was higher for males (48.3 ± 10.2) as compared to females (48.2 ± 10.5), but this was not significant statistically (P = 0.883).

On the other hand, females had higher mean scores for comprehensibility (19.8 ± 5.5) (P = 0.722) and manageability (13.9 ± 5.9) (P = 0.063) when compared to males. Nonetheless, meaningfulness component was statistically significant with higher mean score in males (48.3 ± 10.2) and lower score in females (48.2 ± 10.5) (P = 0.003).

A statistically significant difference was noted for overall mean SOC scores and its components for the different socioeconomic classes based on Kuppuswamy scale. For the overall mean SOC scores and manageability component, upper class (I) had the highest score (52.7 ± 9.4, 16.2 ± 4.8) and lower class (V) had the least score (40.3 ± 5.7, 7.3 ± 5.9) (P = 0.000). Furthermore, comprehensibility component had higher mean score for lower class (V) (21.1 ± 3.4) and lower score for lower middle class (III) (18.5 ± 6.1) (P = 0.011). On the other hand, the meaningfulness component had high mean score in upper middle class (II) (16.2 ± 4.9) and low mean score in lower class (V) (11.9 ± 2.3) (P = 0.000) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of the overall mean sense of coherence and its components scores based on Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale

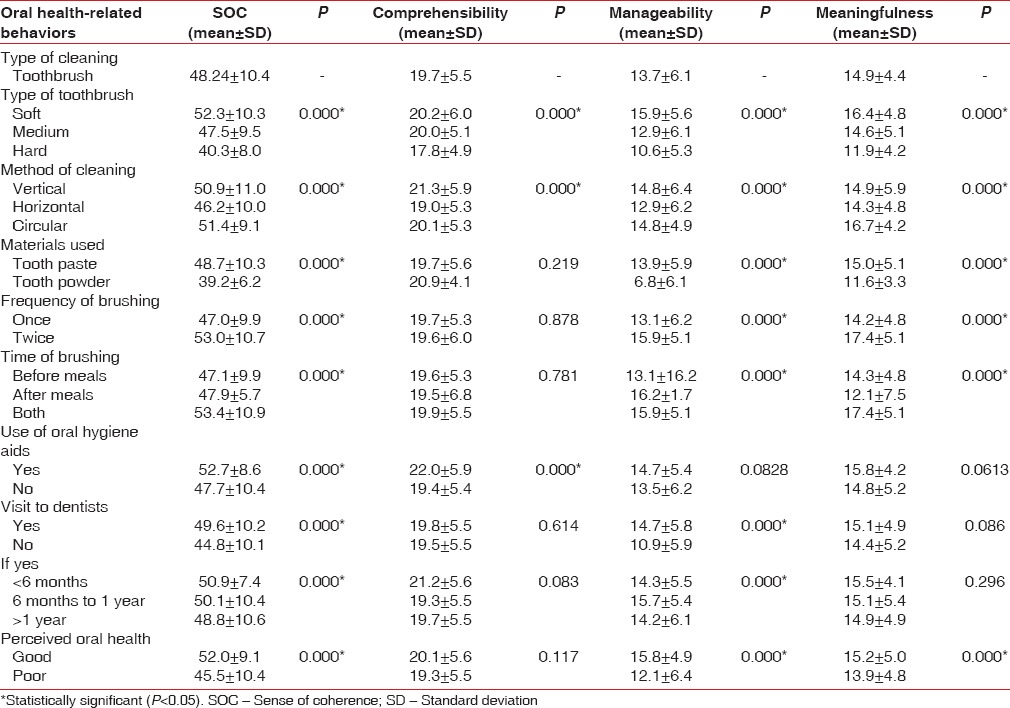

A statistically significant difference was seen for overall SOC based on oral health-related behaviors. For manageability and meaningfulness component, use of oral hygiene aids was not statistically significant. Likewise, for meaningfulness component, visit to dentist did not influence significantly. On the other hand, for the comprehensibility component, materials used for cleaning teeth, frequency of brushing, time of brushing, and visit to dentist were not statistically significant. The perceived oral health was statistically significant with SOC and its components manageability and meaningfulness [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of the overall mean sense of coherence and its components scores based on oral health behaviors

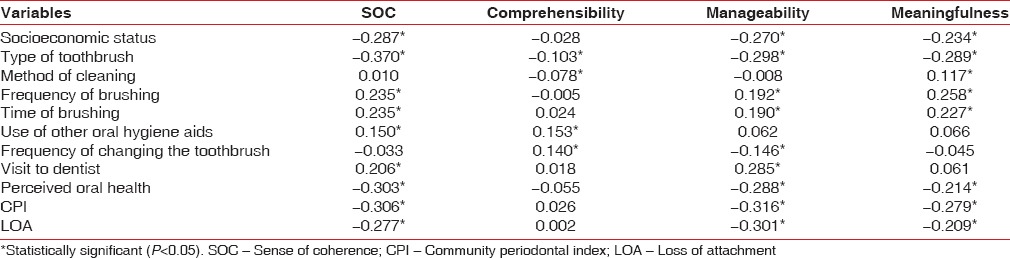

The overall SOC showed significantly negative correlation for socioeconomic status, type of toothbrush, perceived oral health, CPI, and LOA whereas a significantly positive correlation was observed for frequency of brushing, time of brushing, use of other oral hygiene aids, and visit to dentist.

The comprehensibility component had statistically negative correlation for type of toothbrush (r = −0.103) and method of cleaning (r = −0.078). On the contrary, a significant positive correlation was found for the use of other oral hygiene aids (r = 0.153) and frequency of changing toothbrush (r = 0.140).

A statistically negative correlation for manageability component was seen with socioeconomic status (r = −0.270), type of toothbrush (r = −0.298), frequency of changing toothbrush (r = −0.146), perceived oral health (r = −0.288), CPI (−0.316), and LOA (r = −0.301). Positive correlation was noted for frequency of brushing (r = 0.192), time of brushing (r = 0.190), and visit to dentist (r = 0.285). All these variables showed statistically significant difference.

The meaningfulness component had statistically negative correlation with socioeconomic status (r = −0.234), type of toothbrush (r = −0.289), perceived oral health (r = −0.214), CPI (r = 0.279), and LOA (−0.209). A positive significant correlation was observed with method of cleaning (r = 0.117), frequency of brushing (r = 0.258), and time of brushing (r = 0.227) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation of socioeconomic status, oral health behaviors, and periodontal status with sense of coherence by Karl Pearson’s correlation coefficient

DISCUSSION

The theory of salutogenesis was proposed by Aaron Antonovsky is based on two concepts: General resistance resources (GRRs) and SOC. The GRRs comprise a broad range of resources such as social support, material resources, coping strategies, and family socialization that neutralizes the effects of stressful life events and promotes successful tension management. The SOC is the central construct of the salutogenic theory which states that in order to create well-being, it is important for people to focus on their resources and capacity rather than on their diseases.[15]

The SOC is a psychosocial factor that enables people to manage tension, identify, and mobilize resources to promote effective coping by finding solutions in a health promotion manner. SOC is the resource for achievement and maintenance of good health. The relationship between SOC and health outcomes has been investigated in many studies,[10,12] but its relationship with oral health has been found only in a few studies.[16,17,18] Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the correlation of the SOC with oral health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and periodontal status among 35–44 years adults visiting Panineeya Mahavidyalaya Institute of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Hyderabad.

The theory purports that the level of SOC that an individual achieves is determined at the age of 30, after which remains relatively stable.[12] Keeping this in mind, 35–44-year-old adults were included in the study. In addition, the WHO suggested this age group as the standard monitoring group for health conditions of adults to determine the level of periodontitis.[14]

In the current study, we have used SOC-13 item questionnaire, which is a short version of the SOC-29 item. This scale was tested and validated in a study conducted by Bonanato et al. and has an advantage over the full version, i.e., it takes less time to complete.[3] Therefore, the short version of SOC (SOC-13) questionnaire was employed in this study.

CPI and LOA indices are established measures for the assessment of periodontal problems in population by the WHO.[14] The major advantages are simplicity, reproducibility, and international uniformity. Therefore, in the present study, these indices were used to determine the periodontal status.

The studies done by Freire et al.[7] and Bernabé et al.[19] revealed that a stronger SOC was significantly associated with better oral health behaviors. Henceforth, in the present study, oral health behaviors were taken into account to know whether SOC influences oral health behaviors among Indian population.

In our study, all the study patients used toothbrush (780, 100) and around 747 (95.8%) preferred using toothpaste and 688 (88.2%) used oral hygiene aids. There were 566 (72.6%) patients who previously visited the dentist. Likewise, in a study done by Lindmark et al.[20] and Boman et al.,[21] majority of study subjects visited dentists for regular checkups.

Furthermore, majority of the study patients used medium type of toothbrush (387, 49.6%) and 59.1% of subjects used horizontal method of tooth cleaning. Therefore, this result enlightens us that study patients had limited knowledge of oral health behaviors, and further, horizontal brushing method and usage of medium type of toothbrush were found to be more injurious to marginal gingiva leading to gingival recession. Hence, these brushing methods should not be encouraged.

The results of the present study showed that 619 brushed once a day and 161 had a habit of brushing twice daily. Literature provided by Ayo-Yusuf et al. on South African adolescents found that 225 had a habit of brushing at least twice a day.[22] On contrary, another study done by Ayo-Yusuf et al. in 2009 among South African adolescents reported that a few subjects (136) do not brush daily.[23] On the other hand, in a study done by Lindmark et al.,[20] Bernabé et al.,[19] and Savolainen et al.,[24] majority of subjects had habit of brushing twice or more number of times.

In the current study, around 57.3% had perceived their oral health as poor and 42.3% perceived as good. On the contrary, a study conducted among Swedish population by Boman et al. reported that only 24% of study subjects perceived their oral health as poor and 76% as good.[21] Nonetheless, in a study by Bernabé et al. in Finnish population, 34% of the study subjects reported poor perceived oral health.[16]

In the present study, 185 (23.7%) patients had healthy periodontal status and only 37 (4.7%) patients had bleeding on probing. In contrary, a study done by Ayo-Yusuf et al. found that 37.4% reported frequent gingival bleeding[22] and one more study by Lindmark et al. reported that 85 study subjects had healthy gingival.[25]

In this study, majority (496, 63.6%) of study subjects had LOA <0–3 mm (code 1). This may be attributed to the fact that the most of the study participants had graduate or postgraduate degree, which shows that they were educated and could maintain better oral health and furthermore most of the subjects visited dentist formerly.

In the current study, though males had higher mean SOC score, it was not significant as compared to females (P = 0.883); however, Dorri et al. among Iranian adolescents revealed that boys had stronger SOC than girls and were statistically significant (P = 0.04).[26]

In the present study, SOC and its components were statistically significant with socioeconomic status. The mean SOC and its component manageability were high among upper class (I) whereas comprehensibility component was high among lower class scores (II) and meaningfulness component among upper middle class (II).

In our study, a significant difference was noted for SOC with oral health-related behaviors (type of brush used, method of cleaning, materials used, frequency of brushing, use of oral hygiene aids, and visit to dentist); this indicates that a stronger SOC was associated with better oral health behaviors. The study done by Lindmark et al. revealed that only tooth-brushing frequency was significantly related with SOC.[18] However, previous studies have shown that strong SOC is associated with tooth-brushing.[22,23]

The SOC and two of its components were significantly and negatively related to CPI and LOA scores. In addition, previous literature[9,16,19,23] found that the subjects with higher SOC have good oral health than subjects with weak SOC. This might be due to the fact that higher SOC among study subjects made them maintain good periodontal status.

In the present study, it was found that good oral health behaviors and good periodontal status were associated with stronger SOC. However, our study has certain limitations such as age-group comparison could not be done. The study was done among people visiting dental hospital and may present with bias; hence, the results cannot be generalized. Furthermore, further investigations should be done among large group of populations to know how SOC is related to oral health and even among all the applicable age-groups. The cross-sectional nature of the study does not permit us to check for causality.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, SOC was positively correlated to all oral health behaviors, except for type of toothbrush used frequency of changing the toothbrush and perceived oral health. The overall SOC was negatively correlated with socioeconomic status. When periodontal status was considered, SOC was negatively correlated with CPI and LOA scores, thus indicating good periodontal status.

The present study concluded that a high level of SOC was associated with good oral health behaviors such as frequency of brushing, time of brushing, use of oral hygiene aids, and visit to dentist, with periodontal status and socioeconomic status.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank her professors and colleagues for guiding her in this endeavor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park K, editor. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 21st ed. Jabalpur: Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2011. Concept of health and disease; pp. 12–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonanato K, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA, Ramos-Jorge ML, Barbabela D, Allison PJ. Relationship between mothers' sense of coherence and oral health status of preschool children. Caries Res. 2009;43:103–9. doi: 10.1159/000209342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghaderi AR, Kumar V, Kumar S. Depression, anxiety and stress among Indian and Iranian students. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2009;35:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisine S, Litt M. Social and psychological theories and their use for dental practice. Int Dent J. 1993;43(3 Suppl 1):279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:725–33. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freire MC, Sheiham A, Hardy R. Adolescents' sense of coherence, oral health status, and oral health-related behaviours. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:204–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sipilä K, Ylöstalo P, Könönen M, Uutela A, Knuuttila M. Association of sense of coherence and clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva Da AN, Mendonca De MH, Vettore MV. A salutogenic approach to oral health promotion. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:521–30. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008001600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson AK, van den Donk M, Hilding A, Östenson CG. Work stress, sense of coherence, and risk of type 2 diabetes in a prospective study of middle-aged Swedish men and women. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2683–9. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawley DJ, Wolfe F, Cathey MA. The sense of coherence questionnaire in patients with rheumatic disorders. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1912–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silarova B, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Studencan M, Ondusova D, Reijneveld SA, et al. Sense of coherence as a predictor of health-related behaviours among patients with coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13:345–56. doi: 10.1177/1474515113497136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:103–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys, Basic Methods. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 1997. Oral Health Assessment Form; pp. 26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freire M, Hardy R, Sheiham A. Mothers' sense of coherence and their adolescent children's oral health status and behaviours. Community Dent Health. 2002;19:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernabé E, Kivimäki M, Tsakos G, Suominen-Taipale AL, Nordblad A, Savolainen J, et al. The relationship among sense of coherence, socio-economic status, and oral health-related behaviours among Finnish dentate adults. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:413–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernabé E, Watt RG, Sheiham A, Suominen-Taipale AL, Uutela A, Vehkalahti MM, et al. Sense of coherence and oral health in dentate adults: Findings from the Finnish health 2000 survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:981–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindmark U, Hakeberg M, Hugoson A. Sense of coherence and its relationship with oral health-related behaviour and knowledge of and attitudes towards oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:542–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernabé E, Watt RG, Sheiham A, Suominen-Taipale AL, Nordblad A, Savolainen J, et al. The influence of sense of coherence on the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status and adult oral health-related behaviours. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:357–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindmark U, Stenström U, Gerdin EW, Hugoson A. The distribution of sense of coherence among Swedish adults: A quantitative cross-sectional population study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:1–8. doi: 10.1177/1403494809351654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boman UW, Wennström A, Stenman U, Hakeberg M. Oral health-related quality of life, sense of coherence and dental anxiety: An epidemiological cross-sectional study of middle-aged women. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayo-Yusuf OA, Reddy PS, van den Borne BW. Adolescents' sense of coherence and smoking as longitudinal predictors of self-reported gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:931–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayo-Yusuf OA, Reddy PS, van den Borne BW. Longitudinal association of adolescents' sense of coherence with tooth-brushing using an integrated behaviour change model. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:68–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savolainen J, Suominen-Taipale AL, Hausen H, Harju P, Uutela A, Martelin T, et al. Sense of coherence as a determinant of the oral health-related quality of life: A national study in Finnish adults. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:121–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindmark U, Hakeberg M, Hugoson A. Sense of coherence and oral health status in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:12–20. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.517553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorri M, Sheiham A, Hardy R, Watt R. The relationship between sense of coherence and toothbrushing behaviours in Iranian adolescents in Mashhad. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]