Abstract

Background

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is the leading cause of death in systemic sclerosis (SSc). Annual screening with echocardiogram (ECHO) is recommended. We present the methodological aspects of a PAH screening programme in a large Australian SSc cohort, the epidemiology of SSc-PAH in this cohort, and an evaluation of factors influencing physician adherence to PAH screening guidelines.

Methods

Patient characteristics and results of PAH screening were determined in all patients enrolled in a SSc longitudinal cohort study. Adherence to PAH screening guidelines was assessed by a survey of Australian rheumatologists. Summary statistics, chi-square tests, univariate and multivariable logistic regression were used to determine the associations of risk factors with PAH.

Results

Among 1636 patients with SSc, 194 (11.9%) had PAH proven by right-heart catheter. Of these, 160 were detected by screening. The annual incidence of PAH was 1.4%. Patients with PAH diagnosed on subsequent screens, compared with patients in whom PAH was diagnosed on first screen, were more likely to have diffuse SSc (p = 0.03), be in a better World Health Organisation (WHO) Functional Class at PAH diagnosis (p = 0.01) and have less advanced PAH evidenced by higher mean six-minute walk distance (p = 0.03), lower mean pulmonary arterial pressure (p = 0.009), lower mean pulmonary vascular resistance (p = 0.006) and fewer non-trivial pericardial effusions (p = 0.03). Adherence to annual PAH screening using an ECHO-based algorithm was poor among Australian rheumatologists, with less than half screening their patients with SSc of more than ten years disease duration.

Conclusion

PAH is a common complication of SSc. Physician adherence to PAH screening recommendations remains poor. Identifying modifiable barriers to screening may improve adherence and ultimately patient outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13075-017-1250-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Systemic sclerosis, Scleroderma, Pulmonary arterial hypertension, Screening algorithm

Background

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystem connective tissue disease (CTD) characterised by vasculopathy and fibrosis [1]. There is no cure for SSc, leading to significant morbidity, mortality and poor health-related quality of life [2, 3].

Cardiopulmonary manifestations, namely interstitial lung disease (ILD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), have replaced SSc renal crisis (SRC) as the leading cause of mortality in SSc [4, 5].

SSc-PAH occurs with a prevalence of 8–12% [6] and is the second most common cause of PAH after idiopathic PAH [7]. PAH is characterised by abnormal proliferation, vasoconstriction and thrombosis of the pulmonary vasculature, leading to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), resulting in right-heart failure and death [8]. Despite new pulmonary vasodilator therapies that improve symptoms and survival [9–16], one-year and three-year survival remains poor (78% and 47%, respectively) [17, 18], less than that of idiopathic and other connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated PAH [18]. Risk factors for the development of SSc PAH include anti-centromere antibody, telangiectasia, calcinosis, oesphageal stricture, sicca symptoms, mild ILD and digital ulcers [19, 20], although none of these perform sufficiently well as indicators in the individual patient and are often inconsistent between studies.

Early recognition of SSc-PAH is difficult as early disease is clinically silent and the heterogeneous nature of SSc makes interpretation of fatigue and dyspnoea challenging [21]. Survival is improved even after adjustment for lead-time bias in SSc-PAH when diagnosed by screening compared with diagnosis during routine care [9–14]. Consequently, annual screening with transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) is recommended [22], regardless of the presence or absence of the aforementioned risk factors, to identify patients who should undergo right-heart catheterisation (RHC) to confirm the diagnosis.

Despite the documented benefit of PAH screening, physician adherence is suboptimal, with one study showing that only 34.7% of patients with SSc had a TTE and 53.1% had PFT in the twelve months prior to PAH diagnosis [23]. Adherence among Australian physicians is no better, with over 40% not adhering to annual screening and even fewer using RHC for PAH diagnosis [24]. Consequently, the Australian Scleroderma Cohort Study (ASCS), a longitudinal multi-centre study, was established in 2007 as a web-based screening platform for the cardiorespiratory manifestations of SSc.

In this paper, we present the methodological aspects of establishing the ASCS and the screening algorithm, the characteristics of patients with SSc with PAH in this cohort and an evaluation of the factors influencing Australian rheumatologists’ adherence to screening guidelines.

Methods

Study centres

The ASCS is a nationwide project wherein patients with SSc are recruited from 13 participating centres across Australia. SSc experts were invited by a core group of rheumatologists to form the Australian Scleroderma Interest Group (ASIG) and to take part in the ASCS through recruitment of patients and collection of data at their centres. Physicians who are not at an ASIG centre and care for patients with SSc are invited to refer patients for the screening service, while ongoing care between screening visits remains their responsibility.

Patients

All patients with SSc, defined according to American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria [25] or Leroy/Medsger criteria [26], and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), as originally described by Sharp et al. [27], are eligible for enrolment. Patients provide written informed consent for collection of de-identified data, chart review, and storage of serum and DNA for future studies. All human research ethics committees of the participating sites have approved ASCS.

Data collection and database

Comprehensive demographic and disease-related data are collected annually and entered into a custom-made database hosted by St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne using a remote secure access token. A log is kept of all users and the database is backed up daily. Logic checks are used to detect errors in data entry and incomplete entries.

Screening algorithm for early detection of PAH

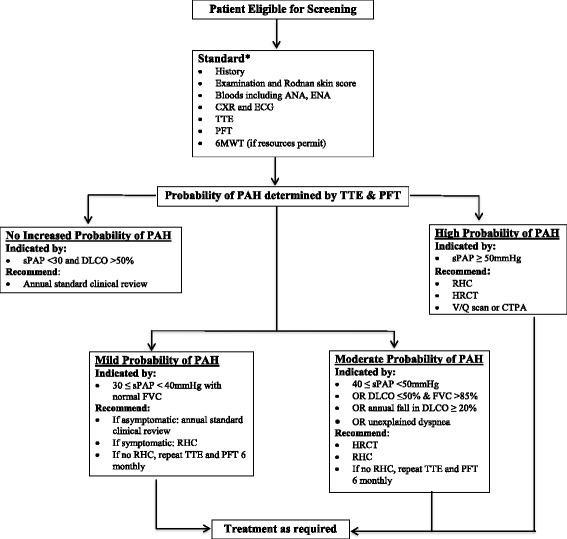

Participation in the ASCS mandates annual application of a PAH screening algorithm created by a panel of Australian rheumatologists, cardiologists and respiratory physicians (Fig. 1) based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines [28, 29]. According to Fig. 1, investigations are recommended for symptomatic patients with low probability of PAH, and irrespective of symptoms for patients with moderate or high probability of PAH [30].

Fig. 1.

Australian Scleroderma Cohort Study algorithm for screening for pulmonary hypertension. ANA antinuclear antibody, ENA extractable nuclear antibody, CXR chest radiograph, ECG electrocardiogram, TTE transthoracic echocardiogram, PFT pulmonary function test, 6MWT six-minute walk test, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, sPAP systolic pulmonary arterial pressure, DLCO diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide corrected for haemoglobin, RHC right-heart catheterization, HRCT high-resolution chest computed tomography, V/Q ventilation perfusion, CTPA computed tomography pulmonary angiography

Clinical decision support tool

If any value falls outside a predetermined range for systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (sPAP) on TTE, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) corrected for haemoglobin, and/or forced vital capacity (FVC) according to the screening algorithm, an email to the treating physician is automatically generated, indicating why the alert has been triggered and recommending a course of action. If the physician chooses not to follow the algorithm he/she must justify this decision.

Adherence to published recommendations for annual PAH screening

Non-ASIG physicians’ screening practices and adherence to published recommendations for PAH screening [24, 28, 29] were assessed by means of a cross-sectional survey (Additional file 1: Table S1 using survey monkey circulated through the Australian Rheumatology Association following the establishment of ASCS in 2007. The survey addressed existing screening practices based on SSc disease subtype and disease duration (early or late defined as <10 or ≥10 years from the first non-Raynaud’s disease manifestation, respectively), barriers to screening encountered by physicians and suggestions for streamlining screening.

Statistics

For the purpose of statistical analysis, de-identified aggregated data are exported in.txt and.xml format. Characteristics of patients in the study are presented as mean (standard deviation (SD)) or number (percentage). We compared dichotomous variables using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test for non-parametric data. All-cause mortality was used for survival analyses. Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves were used to estimate survival in patients with SSc-PAH diagnosed at first screen versus subsequent screen. The date of PAH diagnosis on RHC was considered the baseline from which survival was calculated. Log-rank and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare survival curves.

Results

Recruitment

A total of 1636 patients were recruited into ASCS from July 2007 to July 2016 (census date). Recruitment comprised new referrals from general practitioners for comprehensive specialist management, and from rheumatologists requesting the PAH screening service only. The number of patients recruited, relative to the predicted prevalence of SSc in Australia [31, 32] and population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics [33] were estimated.

Patient characteristics and follow up

Of the 1636 patients, 1243 (75.9%) had been seen within the 18 months before the census date and were considered “current” (Table 1). The period of 18 months was selected to allow for delays in data entry. Patient characteristics and follow-up status are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients recruited up to July 2016 (n = 1636)

| Characteristic | Number (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Patient number | 1636 |

| Gender (female:male) | 6.4:1 (86.1% vs 13.9%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 1390 (91.9%) |

| Asian | 75 (4.9%) |

| Aboriginal-Islander | 18 (1.2%) |

| Hispanic | 11 (0.7%) |

| Other | 19 (1.3%) |

| Age at recruitment, mean ± SD, years | 57.2 ± 12.8 |

| Disease duration at recruitmenta, years | 10.9 ± 10.2 |

| Recruited within 4 years of first non-Raynaud’s feature | 435 |

| Age at diagnosis of PAH if present, years | 62.9 ± 11.1 |

| Number of study visits | |

| One | 364 (22.3%) |

| Two | 325 (19.9%) |

| Three | 216 (13.2%) |

| Four | 199 (12.2%) |

| Five | 165 (10.1%) |

| Six | 119 (7.3%) |

| Seven | 71 (4.3%) |

| Eight | 79 (4.8%) |

| Nine | 84(5.2%) |

| Ten | 14 (0.9%) |

| Duration of follow up, mean ± SD, years | 3.7 ± 2.7 |

| Patient status | |

| Current | 1243 (76.5%) |

| Withdrawn | 101 (6.2%) |

| Dead | 220 (13.5%) |

| Lost to follow up | 61 (3.8%) |

| Disease subtype | |

| Limited | 1122 (68.6%) |

| Diffuse | 377 (23.0%) |

| MCTD | 83 (5.3%) |

| Autoantibody profile | |

| ANA positive (n = 1508) | 1418 (94.0%) |

| Anti-centromere (n = 1497) | 673 (44.9%) |

| Anti-Scl70 (n = 1483) | 205 (13.8%) |

| Anti-RNAP (n = 794) | 125 (13.1%) |

aDisease duration from first non-Raynaud manifestation. Numbers of variables analysed (n =) are included in each section of the table to acknowledge any missing data. Patient status: current patients were defined as being seen in the last 2 years, withdrawn patients have withdrawn their consent from participating in the database and lost to follow up is defined as patients who, despite multiple attempts, we have been unable to contact for >18 months. PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, MCTD mixed connective tissue disease, ANA antinuclear antibody, Anti-RNAP anti-RNA polymerase

Patients with limited disease (lcSSc) were older at recruitment than patients with diffuse disease (dcSSc) (58.8 ± 12.2 vs 53.1 ± 13.1 years, p < 0.001) with longer disease duration from first non-Raynaud’s clinical manifestation (12.2 ± 10.8 vs 8.1 ± 8.7 years, p < 0.001). ILD was more prevalent in the patients with dcSSc (40.9% vs 21.1%) but there was no significant difference in the prevalence of PAH (10.1% vs 12.7%, p = 0.40) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with SSc by disease subset

| Limited | Diffuse | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1122 | n = 377 | ||

| mean ± SD or % | mean ± SD or % | ||

| Age at recruitment, years | 58.8 ± 12.2 | 53.1 ± 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Female | 89.5% | 74.9% | <0.001 |

| Disease durationa (non-Raynaud) at recruitment, years | 12.2 ± 10.8 | 8.1 ± 8.7 | <0.001 |

| Anti-centromere pattern ANA | 59.2% | 9.6% | <0.001 |

| Scl 70 positive | 8.9% | 31.1% | <0.001 |

| RNA polymerase III positive | 5.4% | 39.6% | <0.001 |

| ILD (HRCT scan) | 236 (21.11%) | 154 (40.9%) | <0.001 |

| PAH (RHC) | 142 (12.7%) | 38 (10.1%) | 0.40 |

| Rodnan skin score (highest ever) | 7.7 ± 5.4 | 22.7 ± 9.9 | <0.001 |

| Digital ulcers ever | 39.6% | 60.8% | <0.001 |

| Joint contractures ever | 28.5% | 71.2% | <0.001 |

| Renal crisis ever | 0.9% | 7.7% | <0.001 |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux | 80.3% | 82.7% | 0.29 |

| Anal incontinence | 27.9% | 25.6% | 0.39 |

ANA antinuclear antibodies, ILD interstitial lung disease, HRCT high-resolution chest computed tomography, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, RHC right-heart catheterisation

aDisease duration defined as from first non-Raynaud’s disease manifestation. Disease manifestations are defined as present if ever present from time of diagnosis of systemic sclerosis (SSc)

In total, 232 patients (14.2%) were diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension (PH). Of these, 194 patients (83.6%) had World Health Organisation (WHO) Group I PAH according to the criteria developed in Nice [34], 15 patients (6.5%) had exercise-induced PH, 18 patients (7.8%) had PH secondary to left ventricular dysfunction (WHO Group 2 PH) and 5 patients (2.2%) had PH secondary to ILD (WHO Group 3 PH). Only patients with WHO Group I PAH were analysed in this study.

At enrollment, 34 (2.1%) patients had previously been diagnosed with PAH and 122 (7.5%) were diagnosed at their first contact with ASCS. Among the latter, 89 (72.9%) had SSc disease duration of ≥4 years and the date of their last TTE was 1.6 ± 4.6 years before enrollment to ASCS, highlighting a lack of adherence to annual PAH screening in the community.

Outcomes of screening in the ASCS

A total of 4326 screening visits were analysed, to determine the success of, and adherence to the PAH screening algorithm (Table 3). Only patients not previously diagnosed with PAH were included. At the first screening visit, sufficient data to apply the screening algorithm were available for 1363 patients. Of these, 101 patients (7.4%) were at high risk of PAH, 121 patients (8.9%) at moderate risk, 358 patients (26.3%) at low risk and 470 patients (34.5%) at no increased risk based on TTE and PFT results. The number of patients with no tricuspid regurgitation (TR) on TTE, and hence inestimable sPAP, was high at 313 (22.9%).

Table 3.

Diagnosis of WHO Group I PAH by risk stratification using the screening algorithm

| No increased probabilitya |

Low probability of PAHa | Moderate probability of PAHa | High probability of PAHa | Missing sPAP | Total with PAH, n | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review number | Screened, n | Normal TTE, n | RHC, n |

PAH, n |

Moderate TTE, n | RHC, n |

PAH, n |

High suspicion TTE, n | RHC, n |

No. with PAH | High probability TTE, n | RHC, n |

PAH, n |

Positive screenc, n |

RHC, n | PAH, n |

|

| 1st screen | 1363 | 470 | 19 | 4 | 358 | 38 | 11 | 121 | 36 | 25 | 101 | 83 | 72 | 313 | 24 | 10 | 122 (8.9%) |

| 2nd screen | 896 | 355 | 6 | 2 | 229 | 5 | 3 | 78 | 10 | 4 | 32 | 11 | 5 | 202 | 8 | 3 | 17 (1.9%) |

| 3rd screen | 679 | 272 | 0 | 0 | 167 | 4 | 1 | 65 | 5 | 3 | 20 | 7 | 6 | 155 | 3 | 1 | 11 (1.6%) |

| 4th screen | 482 | 199 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 3 | 0 | 42 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 103 | 1 | 0 | 5 (1.0%) |

| 5th screen | 361 | 149 | 0 | 0 | 104 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 74 | 1 | 0 | 2 (0.6%) |

| 6th screen | 235 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 72 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.9%) |

| 7th screen | 162 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 1 | 0 | 0 (0.0%) |

| 8th screen | 104 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0.0%) |

| 9th screen | 43 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3%) |

| 10th screen | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Total | 4326 | 1670 | 25b (1.5%) | 6a (24%) | 1142 | 53b (4.6%) | 17a (32.7%) | 386 | 60b (15.5%) | 36a (60%) | 186 | 110b (59%) | 87a (79.1%) | 942 | 38b (4%) | 14a (36.8%) | 160 (11.7%) |

aProbability of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH): no increased probability of PAH was indicated by systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (sPAP) <30 and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide corrected for haemoglobin (DLCO) >50%, low probability of PAH was indicated by 30 ≤ sPAP <40 mmHg with normal forced vital capacity (FVC) and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), moderate probability of PAH was 40 ≤ sPAP <50 mmHg OR DLCO ≤50% and FVC <85% or annual fall in DLCO ≥20% or unexplained dyspnea and high probability of PAH was indicated by sPAP ≥50 mmHg.

bPercentage of patients who were detected by transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) to be in a risk category and underwent right-heart catheterisation (RHC)

cPercentage of patients who underwent RHC and were diagnosed with World Health Organisation (WHO) Group I PAH

At the first screening visit, 157 of the 580 (27.1%) patients at low (38/358), moderate (36/121), or high (83/101) risk of PAH underwent RHC. WHO Group 1 PAH was diagnosed in 122 patients (8.9% of the cohort), including 4 of 19 (21.0%) patients with a normal TTE and 10 of 24 patients (41.7%) with a missing sPAP on TTE due to lack of a TR jet. The patients in the latter two groups were referred for RHC due to reduced exercise capacity and/reduced DLCO. Only 4% of the patients with no TR were referred for RHC but 36.8% of these were diagnosed with WHO Group 1 PAH. At the physician’s discretion and based on other indicators such as patient symptoms and TTE parameters, patients whose initial RHC was negative for PAH were considered for future RHC.

The screening algorithm correctly identified patients at increased risk of PAH and stratified them by level of risk. The higher the probability of PAH, the more likely PAH was to be identified on RHC (Table 3). A new diagnosis of WHO Group I PAH was made in 160 patients from 4326 (3.7%) screening visits (115/1122 with lcSSc, 32/377 with dcSSc and 10/83 with MCTD), giving a prevalence of PAH of 11.8% (10.3% in lcSSc, 8.5% in dcSSc and 12.0% in MCTD). The annual prevalence of PAH was 1.4% (1.2% in lcSSc, 0.9% in dcSSc, 0.4% in MCTD). All patients were treated with specific PAH therapy.

Characteristics of patients with PAH

Patients with PAH were significantly older than patients without PAH (63.1 vs 56.3 years, p < 0.001), had longer disease duration (13.6 vs 10.4 years, p < 0.001) and were in WHO Functional Class III/IV (85.0% vs 21.7%, p < 0.001) (Table 4). Clinical manifestations and autoantibody status are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients with SSc by PAH status

| PAH | No PAH | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD or % | mean ± SD or % | ||

| Number of patients | 209 | 1283 | |

| Age at recruitment, years | 63.1 ± 10.4 | 56.3 ± 12.7 | <0.001 |

| Disease duration at recruitment, yearsa | 13.6 ± 11.5 | 10.4 ± 9.9 | <0.001 |

| Female | 87.1% | 86.2% | 0.88 |

| Limited disease subtype | 73.9% | 70.3% | 0.43 |

| Anti-centromere pattern ANA | 52.6% | 44.1% | 0.02 |

| Scl 70 positive | 6.9% | 15.2% | 0.003 |

| RNA polymerase III positive | 14.4% | 12.9% | 0.65 |

| Digital ulcers ever | 53.0% | 41.9% | 0.003 |

| Telangiectasia ever | 91.4% | 82.4% | <0.001 |

| Calcinosis ever | 53.3% | 34.7% | <0.001 |

| Joint contractures ever | 45.8% | 35.7% | 0.007 |

| GORD | 45.9% | 45.3% | 0.48 |

| Bowel dysmotility | 27.3% | 22.7% | 0.15 |

| Anal incontinence | 32.1% | 25.7% | 0.05 |

| WHO Functional Class | |||

| Class I | 4 (2.1%) | 467(39.1%) | <0.001 |

| Class II | 25 (12.9%) | 469 (39.2%) | |

| Class III | 106 (54.9%) | 238 (19.9%) | |

| Class IV | 58(30.1%) | 22(1.8%) | |

| NT-pro-BNP | 218.9 ± 285.7 | 75.1 ± 159.8 | 0.005 |

PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, ANA antinuclear antibodies, 6MWD six minute walk distance, mPAP mean pulmonary arterial pressure, mRAP mean right atrial pressure, PVR pulmonary vascular resistance, GORD gastro-oesphageal reflux disease, WHO World Health Organisation, NT-pro-BNP N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide

aDisease duration defined as from first non-Raynaud’s disease manifestation

Disease manifestations defined as present if ever present from systemic sclerosis (SSc) diagnosis

Characteristics of patients with PAH diagnosed on first screen compared with patients whose PAH was diagnosed on subsequent screens

To assess whether the ASCS screening programme succeeded in detecting PAH at an earlier stage, we divided our PAH cohort into those patients whose PAH was detected on first screening and those whose PAH was detected on the second or subsequent screen (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of demographic, clinical and haemodynamic characteristics of patients with PAH diagnosed at first screen and PAH diagnosed at subsequent screens

| Characteristic | PAH detected on first screening | PAH detected on subsequent screening | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD or % | mean ± SD or % | ||

| Number of patients | 122 | 38 | |

| Age at PAH diagnosis | 63.9 ± 11.0 | 62.7 ± 9.5 | 0.56 |

| Disease duration at PAH diagnosis | 13.4 ± 12.8 | 14.6 ± 8.7 | 0.62 |

| Female | 96 (85.7%) | 32 (84.2%) | 0.82 |

| Disease subtype | |||

| Limited | 81 (75.7%) | 23 (62.2%) | 0.03 |

| Diffuse | 17 (15.9%) | 13 (35.1%) | |

| MCTD | 9 (8.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | |

| Status | |||

| Alive | 54 (48.2%) | 26 (68.4%) | 0.03 |

| Dead | 55 (49.1%) | 10 (26.3%) | |

| Withdrawn | 3 (2.7%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Unable to contact | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Follow up, years | 3.3 ± 2.4 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| WHO class at PAH diagnosis | |||

| Class I | 4 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.01 |

| Class II | 16 (16.2%) | 15 (40.5%) | |

| Class III | 63 (75.9%) | 20 (54.1%) | |

| Class IV | 16 (16.2%) | 2 (5.4%) | |

| 6MWD at PAH diagnosis | 295.9 ± 118.3 | 340.6 ± 115.6 | 0.05 |

| mPAP on RHC | 38.2 ± 11.4 | 32.5 ± 8.3 | 0.005 |

| mRAP on RHC | 9.7 ± 8.5 | 8.4 ± 3.9 | 0.40 |

| PVR on RHC | 5.5 ± 3.1 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 0.005 |

| CI on RHC | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 0.87 |

| Pericardial effusion | 16 (16.0%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.03 |

Probability of PAH

PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, MCTD mixed connective tissue disease, WHO World Health Organisation, 6MWD six-minute walk distance, mPAP mean pulmonary arterial pressure, RHC right-heart catheterization, mRAP mean right atrial pressure, PVR pulmonary vascular resistance, CI cardiac index, NT-pro-BNP N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide

We believe that PAH detected on first screen were likely to be a “delayed diagnosis” in patients who were referred to ASCS due to symptoms or clinical suspicion of PAH, whereas PAH detected on subsequent screens was more likely to be an “incident” PAH identified on earlier screening.

Patients diagnosed with PAH on subsequent screens compared with first screen were more likely to have dcSSc (35.1% vs 15.9%, p = 0.03), be in a better WHO functional class (54.1% vs 75.9% in Class III, 5.4% vs 16.2% in Class IV, p = 0.01) and have less advanced PAH at diagnosis evidenced by lower mPVR (3.8 vs 5.5, p = 0.005), higher mean 6MWD (340.6 vs 295.9, p = 0.05), lower mPAP (32.5 vs 38.2, p = 0.005), and fewer non-trivial pericardial effusions (2.7% vs 16.0%, p = 0.03).

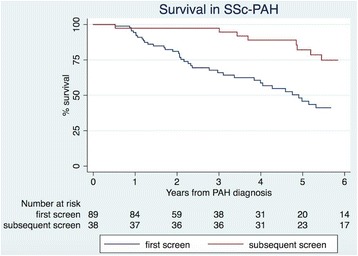

PAH treatment with combination therapy and anticoagulation therapy was prescribed at a similar rate in those diagnosed at subsequent screens (36.8% and 28.9%, respectively) and those diagnosed at first screen (32.1% and 26.8%, respectively). Three-year survival from the time of PAH diagnosis was better in those diagnosed on subsequent screen compared with those diagnosed at first screen as outlined in Fig. 2 (94.7% vs 42.7%, p < 0.001) and mean time to death was longer in those diagnosed with PAH on subsequent screens compared with those diagnosed at first screen (4.7 ± 2.3 vs 2.3 ± 2.3, p < 0.001). PAH was the direct cause of death in 100% of patients diagnosed on subsequent screen and in 92.7% of those diagnosed on first screen (p = 0.40).

Fig. 2.

Survival in systemic sclerosis (SSc) with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) according to the screening visit when the diagnosis was made (first vs subsequent)

Adherence to the ASCS screening algorithm

ASIG physicians’ adherence to PAH screening guidelines was high with 84.4% of patients undergoing annual screening over a ten-year period. Despite the screening algorithm (Fig. 1) mandating that patients at moderate or high risk of PAH should undergo RHC, only 29.7% (170/572) had RHC. Even among those in the high probability group, only 59.1% of patients underwent RHC. Physician justification for not performing RHC predominantly related to their WHO functional class. In 50.5% of cases, RHC was not performed as the patient was in WHO Functional Class I (31.6%), or Class II (14.7%) or was not dyspnoeic (4.2%). In 18.9% of cases, the physician referred the patient to another specialist for their opinion, most commonly a cardiologist or respiratory physician. In 16.8% of cases, the physician was deterred from arranging RHC due to the presence of mild ILD that they felt accounted for the TTE or PFT result. The remaining justifications included a plan to repeat the TTE and/or PFT at a later date (4.2%), patient refusal to have RHC (2.1%), terminal malignancy (2.1%) and no access to RHC (1.1%).

Adherence to PAH screening guidelines by Australian rheumatologists after the establishment of the ASCS screening programme in 2007

Of 334 non-ASIG Australian rheumatologists, 52 responded to the survey on screening practices and barriers to screening (Additional file 1: Table S1). The majority (88.9%) reported screening asymptomatic patients for PAH regularly. Just over half of the respondents ordered annual screening for their asymptomatic patients with early SSc (lcSSc 58.9%, dcSSc 52.6%), with even fewer screening annually in late disease (lcSSc 38.5%, dcSSc 43.6%). All respondents (100%) would investigate their patients with symptoms consistent with PAH. In early symptomatic SSc (with breathlessness or reduced exercise tolerance), the majority of respondents would screen on a six-monthly (51.2%) or annual basis (33.6%). In late symptomatic SSc, 38.9% of respondents would screen their patients six-monthly and 41.2% of respondents would screen annually. Alarmingly, 17.5% of respondents would only screen symptomatic patients every two years.

Explanations for not following guidelines for PAH screening included cost of screening (60%) and concerns about how to interpret the results (80%). In order to improve screening, 50% of respondents felt that they required better guidelines for the selection and frequency of screening tests, 44.7% wanted a reminder system, 42.1% wanted guideline simplification but only 31.6% felt that access to an experienced screening centre would be helpful. If reimbursed by Medicare Australia, 76.3% of respondents would consider the use of a blood test such as N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) a major advance.

Discussion

We present the ASCS as a model of multi-centre web-based data collection and decision support for applying a PAH screening algorithm in patients with SSc. Between 2007 and 2016, 1636 patients with SSc were recruited, an estimated 30.9% of all Australian patients with SSc based on a prevalence of 20 per 100,000 people. As Australia has such sparse population density and SSc is a low-frequency disease, such multicentre collaborations are required in order to recruit and retain sufficient patients for a longitudinal observational study.

The patient characteristics of our cohort are comparable to those of other large multi-centre cohorts indicating that a representative sample is being recruited [35]. As a result of screening, 160 patients were diagnosed with PAH over a ten-year period, providing an annual PAH of 1.4%, consistent with that of the French ItinerAIR-Sclerodermie Study of 0.6% [36] and a prevalence of 11.8% consistent with worldwide data [13, 36–39].

As in other cohorts [40, 41], patients with PAH were older, had longer disease duration from the first non-Raynaud’s clinical manifestation, were more likely to be anti-centromere (ACA)-positive and to have digital ulcers, telangiectasia, calcinosis and joint contractures compared to those without PAH. Patients with PAH detected on the second or subsequent screen were more likely to have dcSSc, be in a better WHO Functional Class at PAH diagnosis and have less advanced PAH, which is consistent with the French data [36] but different from the classical teaching that PAH more commonly develops in patients with lcSSc [42].

Additionally, patients with PAH diagnosed on subsequent screen compared with first screen had significantly improved survival (p < 0.001) and a longer mean time to death (4.7 ± 2.3 vs 2.3 ± 2.3, p < 0.001), which may in part be due to lead-time bias. Our one-year and three- year survival in patients diagnosed with PAH on subsequent visits are similar to the survival rates in the PHAROS registry [14], one of the few other studies evaluating survival in incident SSc-PAH diagnosed on RHC. These survival rates are higher than those reported in other registries containing a mixture of patients with both incident and prevalent SSc-PAH or PAH diagnosed on TTE rather than RHC [38, 43, 44]. Diagnosis of early PAH is particularly important as patients with early PAH can progress rapidly, supporting the need for early treatment in this patient population [12].

Despite the majority of patients in the ASCS being screened annually, only 29.7% (170/572) of patients deemed at moderate or high risk of PAH were referred for RHC, predominantly due to preservation of functional class limiting patient eligibility for PBS-funded PAH therapy. Concern about the small but documented risk involved in RHC may also have deterred physicians from referring for RHC but this information was not specifically sought. These results highlight external factors that limit adherence to international screening recommendations.

The number of patients with no TR on TTE, and hence inestimable sPAP, was high at 21.8%, but consistent with the 20–30% reported in the literature [45]. Only 4% of these patients were referred for RHC, with 36.8% diagnosed with WHO Group 1 PAH. This highlights the need for a non-TTE dependent method of PAH screening and supports the emerging role of NT-pro-BNP, which is increased in PAH and in those at increased risk [46]. This test is not currently reimbursed for this indication in Australia and thus is not often performed.

Since the establishment of ASCS in 2007, Australian rheumatologists’ adherence to screening guidelines has improved, with 88.9% of physicians regularly screening asymptomatic patients with SSc for PAH compared with 55.8% previously [29]. Of those who did not perform TTE for PAH screening, 50% reported this was due to difficulty assessing the right heart pressures with TTE. Referral of these patients to a tertiary screening centre may overcome this obstacle. To our knowledge, there have been no other studies addressing physicians’ perceived barriers to SSc-PAH screening.

Limitations to our study include the potential for lead-time and length-time bias to impact on the survival benefit seen in PAH detected with screening. However, patients detected by screening were functionally impaired at the time of diagnosis and were all commenced on PAH therapy, indicating that their physician felt that their PAH required treatment. Our data analyses were conducted in patients who underwent all procedures listed in our screening algorithm; therefore, the incidence of PAH in our study may be an underestimate, although consistent with the literature. Additionally, only 15.6% of non-ASIG Australian rheumatologists responded to our survey on PAH screening adherence. Therefore these particular results may not be a true reflection of rheumatologists nationwide.

Conclusion

SSc-PAH is a tragic consequence of SSc, which despite advances in therapy, is the leading cause of SSc-related death. Screening with a web-based algorithm can identify patients with earlier PAH and improve outcomes. Identifying modifiable barriers to screening may improve adherence and ultimately patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all investigators of the Australian Scleroderma Interest Group (ASIG) including Catherine Hill, Adelaide, South Australia; Sue Lester, Adelaide, South Australia; Peter Nash, Sunshine Coast, Queensland; Gian Ngian, Melbourne Victoria; Mandana Nikpour, Melbourne, Victoria; Susanna Proudman, Adelaide, South Australia; Maureen Rischmueller, Adelaide, South Australia; Janet Roddy, Perth, Western Australia; Joanne Sahhar, Melbourne, Victoria; Wendy Stevens, Melbourne, Victoria; Gemma Strickland, Geelong, Victoria; Vivek Thakkar, New South Wales; Jenny Walker, Adelaide, South Australia; Jane Zochling, Hobart, Tasmania.

Funding

This work was supported by Scleroderma Australia, Arthritis Australia, Actelion Australia, Bayer, CSL Biotherapies, GlaxoSmithKline Australia and Pfizer. Dr Morrisroe holds an NHMRC Scholarship (APP1113954). Dr Nikpour holds an NHMRC Fellowship (APP1071735).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Authors’ contributions

KM: study design, data analysis, interpretation of results and preparation of the manuscript. WS: study design, data collection, interpretation of results and preparation of the manuscript. JS: data collection and preparation of the manuscript. CR: data analysis and preparation of the manuscript. SP: study design, data collection, interpretation of results and preparation of manuscript. MN: study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results and preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All of the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided written informed consent for collection of de-identified data, chart review, and storage of serum and DNA for use in research studies including publications. All human research ethics committees of the participating sites have approved the ASCS (Royal Perth Hospital in Western Australia, Royal Adelaide and The Queen Elizabeth Hospitals in South Australia, Sunshine Coast Rheumatology and Prince Charles Hospital in Queensland, John Hunter, Royal Prince Alfred, Royal North Shore and St George Hospitals in New South Wales, Canberra Rheumatology in the Australian Capital territory, St Vincent’s Hospital and Monash Medical Centre in Victoria and The Menzies Institute in Tasmania).

Abbreviations

- ASCS

Australian Scleroderma Cohort Study

- ASIG

Australian Scleroderma Interest Group

- DLCO

Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide corrected for haemoglobin

- dcSSc

Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis

- HRCT

High-resolution computed tomography

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- lcSSc

Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis

- MCTD

Mixed connective tissue disease

- NT-pro-BNP

N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide

- PAH

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PH

Pulmonary hypertension

- RFTs

Respiratory function tests

- RHC

Right-heart catheterisation

- SSc

Systemic sclerosis (also known as systemic scleroderma)

- sPAP

Systolic pulmonary arterial pressure

- TR

Tricuspid regurgitation

- TTE

Transthoracic echocardiogram

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Additional file

Cross-sectional survey of physician adherence to PAH screening recommendations. (DOC 97 kb)

Contributor Information

Kathleen Morrisroe, Email: kbmorrisroe@gmail.com.

Wendy Stevens, Email: Wendy.Stevens@svha.org.au.

Joanne Sahhar, Email: josahhar@bigpond.com.

Candice Rabusa, Email: Candice.Rabusa@svha.org.au.

Mandana Nikpour, Email: m.nikpour@unimelb.edu.au.

Susanna Proudman, Email: susanna.proudman@sa.gov.au.

the Australian Scleroderma Interest Group (ASIG):

Catherine Hill, Sue Lester, Peter Nash, Gian Ngian, Mandana Nikpour, Susanna Proudman, Maureen Rischmueller, Janet Roddy, Joanne Sahhar, Wendy Stevens, Gemma Strickland, Vivek Thakkar, Jenny Walker, and Jane Zochling

References

- 1.Marie I, Jouen F, Hellot MF, Levesque H. Anticardiolipin and anti-beta2 glycoprotein I antibodies and lupus-like anticoagulant: prevalence and significance in systemic sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(1):141–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thombs BD, Taillefer SS, Hudson M, Baron M. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):1089–97. doi: 10.1002/art.22910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poole JL, Steen VD. The use of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) to determine physical disability in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4(1):27–31. doi: 10.1002/art.1790040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, Airo P, Cozzi F, Carreira PE, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1809–15. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.114264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao Y, Thakkar V, Stevens W, Morrisroe K, Prior D, Rabusa C, et al. A comparison of the predictive accuracy of three screening models for pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:7–18. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0517-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(9):1023–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1668OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):343–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau EM, Humbert M, Celermajer DS. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(3):143–55. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phung S, Strange G, Chung LP, Leong J, Dalton B, Roddy J, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in an Australian scleroderma population: screening allows for earlier diagnosis. Intern Med J. 2009;39:682–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komocsi A, Vorobcsuk A, Faludi R, Pinter T, Lenkey Z, Kolto G, et al. The impact of cardiopulmonary manifestations on the mortality of SSc: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(6):1027–36. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galie N, Rubin L, Hoeper M, Jansa P, Al-Hiti H, Meyer G, et al. Treatment of patients with mildly symptomatic pulmonary arterial hypertension with bosentan (EARLY study): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9630):2093–100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humbert M, Yaici A, de Groote P, Montani D, Sitbon O, Launay D, et al. Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis: clinical characteristics at diagnosis and long-term survival. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3522–30. doi: 10.1002/art.30541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung L, Domsic RT, Lingala B, Alkassab F, Bolster M, Csuka ME, et al. Survival and predictors of mortality in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: outcomes from the pulmonary hypertension assessment and recognition of outcomes in scleroderma registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(3):489–95. doi: 10.1002/acr.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barst RJ, Gibbs JS, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, Rubin LJ, et al. Updated evidence-based treatment algorithm in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1 Suppl):S78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galie N, Barbera JA, Frost AE, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, et al. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):834–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Peacock AJ, Corris PA, Gibbs JS, Vrapi F, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(2):151–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-953OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Launay D, Sitbon O, Hachulla E, Mouthon L, Gressin V, Rottat L, et al. Survival in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1940–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrisroe K HM, Stevens W, Rabusa C, Proudman S, Nikpour M, the Australian Scleroderma Interest Group (ASIG). Risk factors for development of pulmonary arterial hypertension in Australian systemic sclerosis patients: results from a large multicenter cohort study. BMC. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Shah AA, Wigley FM, Hummers LK. Telangiectases in scleroderma: a potential clinical marker of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(1):98–104. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proudman S, Stevens W, Sahhar J, Celermajer D. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: the need for early detection and treatment. Intern Med J. 2007;37(7):485–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(17):1573–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauling JD, McHugh NJ. Evaluating factors influencing screening for pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis: does disparity between available guidelines influence clinical practice? Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(2):357–61. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangat P, Conron M, Gabbay E, Proudman SM. Scleroderma lung disease, variation in screening, diagnosis and treatment practices between rheumatologists and respiratory physicians. Intern Med J. 2010;40(7):494–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.01990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2737–47. doi: 10.1002/art.38098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeRoy EC, Medsger TA., Jr Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(7):1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp GC, Irwin WS, Tan EM, et al. Mixed connective tissue disease: an apparently distinct rheumatic disease syndrome, associated with a specific antibody to extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) Am J Med. 1972;52(2):148–59. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery J-L, Barbera JA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(6):1219–63. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00139009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaisson NF, Hassoun PM, Chaisson NF, Hassoun PM. Systemic sclerosis- associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2013;144(4):1346–1356. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Englert H, Small-McMahon J, Davis K, O'Connor H, Chambers P, Brooks P. Systemic sclerosis prevalence and mortality in Sydney 1974-88. Aust NZ J Med. 1999;29(1):42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1999.tb01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandran G, Smith M, Ahern MJ, Roberts-Thomson PJ. A study of scleroderma in South Australia: prevalence, subset characteristics and nailfold capillaroscopy. Aust NZ J Med. 1995;25(6):688–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1995.tb02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Statistics ABo. 2012.

- 34.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2014;42(Suppl 1):45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan X, Pope J, Baron M. What is the relationship between disease activity, severity and damage in a large Canadian systemic sclerosis cohort? Results from the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group (CSRG) Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(9):1205–10. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hachulla E, de Groote P, Gressin V, Sibilia J, Diot E, Carpentier P, et al. The three-year incidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis in a multicenter nationwide longitudinal study in France. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(6):1831–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, Mardekian J, Sanders KN, Mychaskiw MA, Thomas J., III Prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with connective tissue diseases: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(10):1519–31. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukerjee D, St George D, Coleiro B, Knight C, Denton CP, Davar J, et al. Prevalence and outcome in systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: application of a registry approach. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(11):1088–93. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.11.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hachulla E, Gressin V, Guillevin L, Carpentier P, Diot E, Sibilia J, et al. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: a French nationwide prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(12):3792–800. doi: 10.1002/art.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yaqub A, Chung L. Epidemiology and risk factors for pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(1):302. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Highland KB. Recent advances in scleroderma-associated pulmonary hypertension. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(6):637–45. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denton CP, Avouac J, Behrens F, Furst DE, Foeldvari I, Humbert M, et al. Systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: Why disease-specific composite endpoints are needed. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(3):114. doi: 10.1186/ar3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung L, Liu J, Parsons L, Hassoun PM, McGoon M, Badesch DB, et al. Characterization of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension from REVEAL: identifying systemic sclerosis as a unique phenotype. Chest. 2010;138(6):1383–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hachulla E, Clerson P, Airò P, Cuomo G, Allanore Y, Caramaschi P, et al. Value of systolic pulmonary arterial pressure as a prognostic factor of death in the systemic sclerosis EUSTAR population. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54(7):1262–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwaiger JP, Khanna D, Gerry CJ. Screening patients with scleroderma for pulmonary arterial hypertension and implications for other at-risk populations. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(130):515–25. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00006013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thakkar V, Stevens W, Prior D, Byron J, Patterson K, Hissaria P, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels predict incident pulmonary arterial hypertension in SSc. Rheumatology. 2012;51:ii8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.