Abstract

Controversies regarding the development of the mammalian infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos veins arise from using topography rather than developmental origin as criteria to define venous systems and centre on veins that surround the mesonephros. We compared caudal‐vein development in man with that in rodents and pigs (rudimentary and extensive mesonephric development, respectively), and used amira 3D reconstruction and cinema 4D‐remodelling software for visualisation. The caudal cardinal veins (CCVs) were the only contributors to the inferior caval (IVC) and azygos veins. Development was comparable if temporary vessels that drain the large porcine mesonephros were taken into account. The topography of the CCVs changed concomitant with expansion of adjacent organs (lungs, meso‐ and metanephroi). The iliac veins arose by gradual extension of the CCVs into the caudal body region. Irrespective of the degree of mesonephric development, the infrarenal part of the IVC developed from the right CCV and the renal part from vascular sprouts of the CCVs in the mesonephros that formed ‘subcardinal’ veins. The azygos venous system developed from the cranial remnants of the CCVs. Temporary venous collaterals in and around the thoracic sympathetic trunk were interpreted as ‘footprints’ of the dorsolateral‐to‐ventromedial change in the local course of the intersegmental and caudal cardinal veins relative to the sympathetic trunk. Interspecies differences in timing of the same events in IVC and azygos‐vein development appear to allow for proper joining of conduits for caudal venous return, whereas local changes in topography appear to accommodate efficient venous perfusion. These findings demonstrate that new systems, such as the ‘supracardinal’ veins, are not necessary to account for changes in the course of the main venous conduits of the embryo.

Keywords: azygos vein, caudal cardinal veins, human, inferior caval vein, mesonephros, mouse, pig

Introduction

The contribution of various embryonic venous systems (caudal cardinal, subcardinal, supracardinal, sacrocardinal and/or medial and lateral sympathetic line veins) to the development of the infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos venous systems of mammalian species remains controversial (Cornillie & Simoens, 2005). Our re‐investigation of the development of the infrahepatic part of the inferior caval and azygos venous systems in humans identified the caudal cardinal veins and its branches as the only contributor to the definitive inferior caval and azygos veins (Hikspoors et al. 2015). The iliac veins arise by a gradual expansion of the caudal cardinal veins into the caudal body region, whereas the renal part of the inferior caval vein originates from vascular sprouts of the caudal cardinal veins that develop in and around the mesonephros to form the so‐called ‘subcardinal’ veins. Despite their cardinal origin we retained the term subcardinal veins, coined by Lewis (1902) because these veins, once formed, drain the mesonephric tubules (Vollmerhaus et al. 2004; Hikspoors et al. 2015).

A major difference between our account and the existing literature is that we described the caudal cardinal veins as undergoing gradual changes in topography as the adjacent organs, such as the lungs, mesonephroi, metanephroi and umbilical arteries, increased in size. In contrast, the original concept posited that new venous systems had to develop before parts of the inferior caval or azygos veins could assume a different topography relative to surrounding tructures (Hochstetter, 1893; Lewis, 1902; Huntington & Mc Clure, 1920; Mc Clure & Butler, 1925; Butler EG, 1927; Butler H, 1950; Gladstone, 1929; Grunwald, 1938). As a result, major differences exist in the historic descriptions of caudal‐vein development in species with a rudimentary mesonephros without glomeruli [mice and rats; (Bremer, 1916; Butler, 1950)] via an intermediate degree of development in, for example, rabbits, cats and humans, to a very extensive and prolonged existence in pig and sheep embryos (Bremer, 1916; Butler, 1927; Tiedemann & Egerer, 1984; Tiedemann, 1976). Butler (1927), for instance, hypothesized that, upon the development of the mesonephroi, the caudal cardinal veins could no longer efficiently drain the dorsal body wall in the lumbar region, so that an additional venous system, the supracardinal veins, had to develop to sustain venous drainage. Additional complexity was added to this model by distinguishing a brief and prematurely arrested development of these supracardinal veins in species with an early decline in the mesonephros (e.g. rabbit), whereas the contribution of the supracardinal veins was considered extensive in species in which the mesonephros persisted after the completion of the embryonic period (human, pig, sheep and cat) (Butler, 1927). However, a more recent study in pig embryos (Cornillie et al. 2008a,b) did not support this hypothesis and, instead, concurred with our findings in human embryos. Although the origin of the azygos venous system from the supracardinal veins is widely accepted (Butler EG, 1927; Butler H,1950; Cornillie et al. 2008b), we showed that, due to growth of underlying lungs, the caudal cardinal veins in human embryos changed their position relative to the sympathetic trunk from dorsolateral to ventromedial in the thoracic region to become the azygos venous system.

The controversies described above with respect to inferior caval and azygos vein development should be addressed and solved if we want to maintain an important paradigm of embryology that the general body plan of all mammalian species is similar. We, therefore, reinvestigated the development of the infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos veins in species with a rudimentary (mice and rats) and an extensive (pigs) mesonephric development, and compared the findings with those of our previous study of human embryos with an intermediate degree of mesonephric development (Hikspoors et al. 2015). The main outcome of our study is that inferior caval and azygos vein development in the species studied is comparable if the vessels that develop temporarily to accommodate the very different sizes of the mesonephros are taken into account.

Materials and methods

Embryos

The collection of mouse and rat embryos was made available by the Department of Anatomy, Embryology, and Physiology of the Academic Medical Center of the University of Amsterdam, while the Department of Morphology, Ghent University, Belgium, made their collection of pig embryos available. The human embryos described or cited in this study were described in our previous study (Hikspoors et al. 2015). We examined 69 mouse, 57 rat and 68 pig embryos between Carnegie stages (CS) 11 and 23. At least two embryos of each gestational age were more extensively evaluated and the best‐preserved specimen was chosen for reconstruction.

Image acquisition and processing

Serial sections, each 7 μm thick, of mouse and rat embryos were stained with haematoxylin and azophloxine, followed by digitization with an Olympus BX51 microscope and the dotslide program (Olympus, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands). Serial sections, each 8 μm thick, of pig embryos were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and were already available as digital images (Cornillie et al. 2008a). Processing of the digital images and voxel size calculation for pig, human, mouse and rat embryos was performed as described (Cornillie et al. 2008a; Hikspoors et al. 2015).

3D reconstruction and visualization

Three‐dimensional (3D) reconstructions were generated with amira software (version 4.0.1 for the pig embryos and version 6.0 for mouse and rat embryos; base package; FEI Visualization Sciences Group Europe, Mérignac Cédex, France) after image loading, alignment and segmentation of the processed digital images. Thereafter, delineation of blood vessels/networks and structures of interest was performed manually.

Polygon meshes were created from all reconstructed materials of the embryos and exported via ‘vrml export’ into cinema 4D (MAXON Computer GmbH, Friedrichsdorf, Germany) to remodel the original amira output into a smooth 3D model. The accuracy of the remodelling process was checked by simultaneous visualization in cinema 4D of the original output from amira and the remodelled cinema model (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Subsequently, the cinema 3D model was exported via ‘wrl export’ into Adobe portable device format (PDF) reader version 9 (http://www.adobe.com) for the generation of 3D interactive PDF files.

Landmarks

Somites, vertebrae, spinal ganglia and intersegmental arteries were used as landmarks for topographic description of structures. Up to CS16, topographic positions were corrected by subtracting 0.5 from the somite number to allow for comparison of younger and older stages based on vertebral number (Hikspoors et al. 2015). The length or position of a structure is, when expressed relative to vertebrae, defined by a transverse slice perpendicular to the (curving) body axis.

Results

To compare venous development of the mouse, rat, pig and human embryos, similar stages were selected based on the atlases of Theiler (1989), O'Rahilly & Müller (2010), Butler & Juurlink (1987), and Evans & Sack (1973). Developmental age is expressed in Carnegie Stages for all species studied (Table 1), with a ‘≈’ sign indicating extrapolation to the non‐human species. The terminology is as used in the previous study (Hikspoors et al. 2015). The development of rat embryos lagged 1.5 days behind that of mouse embryos (Schneider & Norton, 1979). The development of the mesonephros and venous system in rats and mice was indistinguishable and is, for that reason, described for the mouse embryo only. The exception is an intermediate stage in azygos vein development that was observed in rat embryos but not in the available mouse embryos.

Table 1.

Comparison of developmental ages in mouse, human and pig embryos. Carnegie stages were established with atlases (Evans & Sack, 1973; Butler & Juurlink, 1987; Theiler, 1989; O'Rahilly & Müller, 2010). Each row indicates mean age (in days) and crown‐rump length (CRL; in mm) of mouse, human and pig embryos belonging to a particular Carnegie stage

| Carnegie | Mouse | Human | Pig | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage (CS) | Days | CRL (mm) | Days | CRL (mm) | Days | CRL (mm) |

| CS11 | 10 | 3.5 | 29 | 3.2 | 16 | 4.5 |

| CS12 | 10.5 | 4.2 | 30 | 3.9 | 17 | 5 |

| CS13 | 11 | 5.5 | 32 | 4.9 | 18 | 4 |

| CS14 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 34 | 6.5 | 19 | 7 |

| CS15 | 12 | 8 | 36 | 7.8 | 21 | 9 |

| CS16 | 12.5 | 9 | 39 | 9.6 | 22 | 11 |

| CS17 | 13 | 10 | 41 | 12.2 | 23 | 13 |

| CS18 | 13.5 | 11 | 44 | 14.9 | 24 | 15 |

| CS19 | 14 | 11.5 | 46 | 18.2 | 26 | 18 |

| CS20 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 49 | 20.7 | 28 | 21 |

| CS21 | 15 | 13 | 51 | 22.9 | 29 | 23 |

| CS22 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 54 | 25.5 | 31 | 27 |

| CS23 | 16 | 15.5 | 56 | 28.8 | 33 | 30 |

Mesonephros development

Mouse

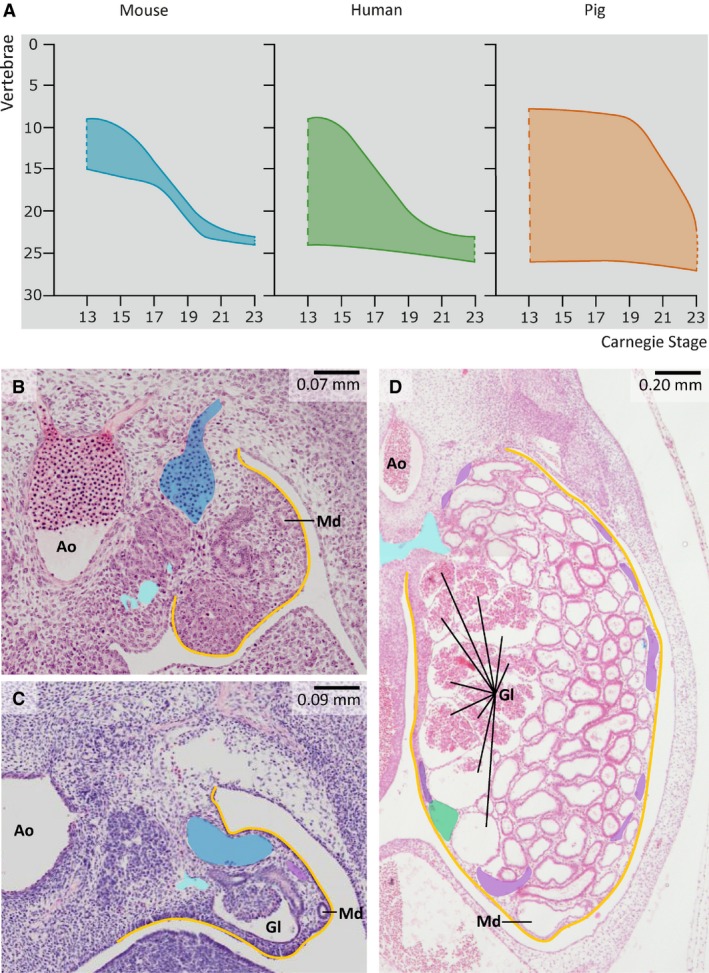

At embryonic day (ED)11 (≈ CS13), the mesonephroi extended from thoracic vertebra (T)2 till T8 and were positioned ventrolateral to the aorta and ventral to the caudal cardinal veins. The mesonephros extended from T3 to T9 in the ED12 (≈ CS15) embryo, from T7 to T10 in the ED13 (≈ CS17) embryo, from T12 to lumbar vertebra (L)2 in the ED14 (≈ CS19) embryo, from L2 to L4 (lateral to the metanephros) in the ED15 (≈ CS21) embryo and from L4 to L5 (just caudal to the metanephros) in the ED16 (≈ CS23) embryo (Fig. 1A; mouse).

Figure 1.

Mesonephric development in mouse, human and pig embryos. (A) Developmental changes in the craniocaudal length of the mesonephros in mouse, human and pig embryos. The cranial mesonephric border is located at the level of T1 in CS13, and at L3/L4 in CS23 in all three species. Note that vertebral levels 1–7 on the y‐axis correspond to C1‐7, levels 8–19 to T1–12, and levels 20–24 to L1–5. (B–D) Difference in mesonephric size and complexity at CS15 in the mouse (B), human (C) and pig embryo (D). The mouse mesonephros (B) only contains mesonephric tubules, whereas glomeruli (Gl) are present on the medial side of the mesonephros and tubules in the remaining part of the mesonephros in human (C) and pig (D) embryos. Yellow – urogenital fold; blue – caudal cardinal vein; cyan – subcardinal vein; purple – venous branches within the urogenital fold and along the mesonephric tubules; dark green – ventral mesonephric vein; Md – mesonephric duct; Ao – aorta.

Human

At CS13 and CS14, the mesonephros spanned from cervical vertebra (C)7 to L5. After CS14, the mesonephroi gradually regressed cranially and extended from T6 to sacral vertebra (S)1 at CS16, from T11 to S2 at CS18, from L2 to S2 at CS20 and from L4 up to S2 at CS23 (Fig. 1A; human).

Pig

The mesonephros in pig embryos extended between T1 and S2 from ED18 (≈ CS13) to ED22 (≈ CS16). Between ED22 and ED26 (≈ CS19), the cranial border of the mesonephros was found at the level of T2 and regressed further to T7 at ED29 (≈ CS21) and to L3 at ED33 (≈ CS23) (Fig. 1A; pig). The caudal mesonephric border extended to S3 between ED26 and ED33.

Comparison of mouse, human and pig mesonephros

In early development (~ CS13) the cranial border of the mesonephros was located at the level of T1/T2 in mouse, human and pig embryos (Fig. 1A). During subsequent development, the cranial border moved to L4/L5 in mouse and human embryos, whereas cranial regression started six stages later (at ≈ CS19) in pig embryos. Strikingly, the caudal border of the mesonephros in human and pig embryos was located at S1–S3 throughout development, whereas the initial length of the mouse mesonephros was shorter and its caudal boundary moved caudally with development. The rodent and human mesonephros, therefore, resembled each other in a similar change in the topography of their cranial boundaries, whereas the human and pig mesonephros had similar, constant caudal boundaries.

At the structural level, the mesonephros of rodents differed from that of humans and pigs by the absence of glomeruli. Furthermore, only relatively simple nephric tubules and an efferent (mesonephric) duct were present (Fig. 1B; Bremer, 1916; Butler, 1927). The human and pig mesonephroi contained well‐developed glomeruli in their medial parts, that is, relatively close to the aorta, whereas their nephric tubules developed into longer, more intricate structures than in rodents (Fig. 1C,D). Four well‐developed lateral branches of the aorta supplied the mesonephric glomeruli up to CS19 and eight arteries thereafter, while the venous network enclosed the tubules. The mesonephric (Wolffian) duct coursed laterally to the mesonephros and medially to the umbilical arteries towards the cloaca in mice. Due to differential growth in the mesonephros, the mesonephric duct gradually changed from dorsolateral to ventrolateral relative to the mesonephros in human (between CS16 and CS18) and even to ventromedial in pig embryos (between ≈ CS16 and ≈ CS19). These changes in position of the mesonephric duct indicate that the mesonephros expanded primarily in its dorsal part.

Infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos vein development in rodents

A pictorial abstract of the development of the infrahepatic caval and azygos veins in rodents is shown in Fig. 2. Furthermore, an interactive PDF of our reconstructed 3D mouse models can be examined in Supporting Information Fig. S2, which allows the reader to follow the changes in shape and topography of the venous systems over time.

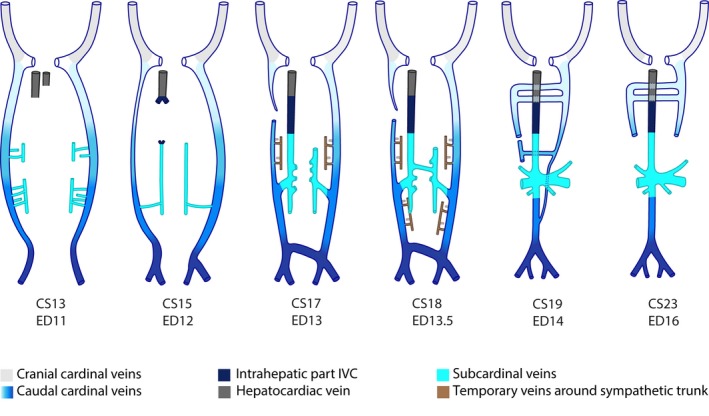

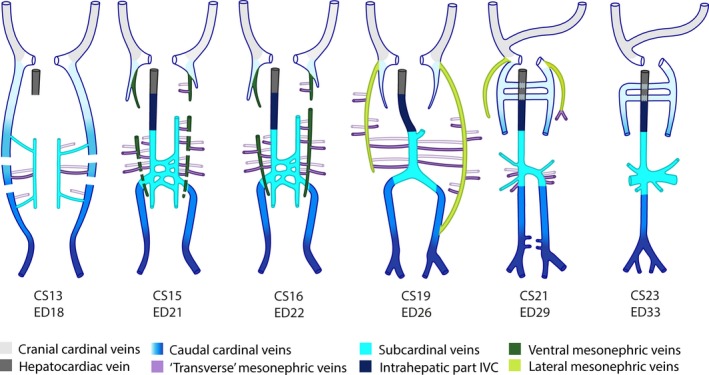

Figure 2.

Pictorial abstract of inferior caval and azygos vein development in rodents. Ventral views. A colour code identifies the respective venous systems. The gradient from light to dark blue depicts the caudal extension of the caudal cardinal veins with time. The smallest vessels (brown) indicate networks that occupy a ventral (filled) or dorsal (without fill) position relative to the sympathetic trunk.

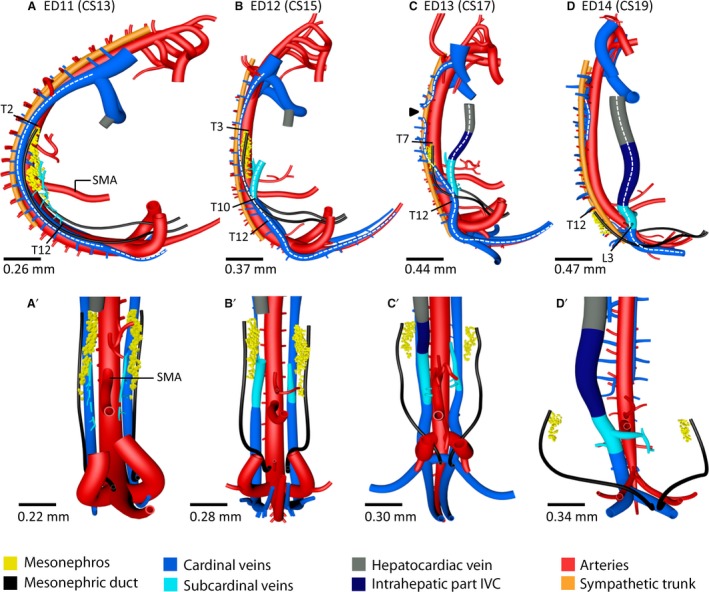

Caudal cardinal vein development

The caudal cardinal veins were first observed in ED9.5–10.5 mouse embryos as small bilateral caudal extensions of the common cardinal vein up to the level of the upper limb. The caudal cardinal veins elongated caudally and passed the umbilical arteries dorsally to reach the most caudal part of the body at ED11 (≈ CS13; Figs 2, 3A,A' and S2A). At this stage the cardinal veins were positioned dorsal to the mesonephroi, dorsolateral to the aorta and median sacral artery, and lateral to the sympathetic trunk (Fig. 3A). As the caudal cardinal veins followed the C‐shaped curvature of the body axis, they acquired a second ‘C’ shape by passing over the umbilical arteries (Fig. 3A; white stippled line). Although no positional changes were observed between ED11 and ED12 (≈ CS15), the right caudal cardinal vein had decreased substantially in diameter between T1 and T10 (≈ CS15; Figs 2, 3B, 4A,A’’, 4B,B’’ and S2B) and had disappeared between T4 and T5 at ED13 [≈ CS17; Figs 2, 3C (arrowhead), 4C,C’’ and S2C]. In this period, the left cardinal vein remained unchanged in size and position. The C‐shaped bend of the left and right caudal cardinal veins across the umbilical arteries became more distinct at ED12 because of the more dorsal position of the umbilical arteries around the developing metanephroi (definitive kidneys). Furthermore, the veins acquired a more ventrolateral position relative to the aorta at the level of T12 (Fig. 3B,C).

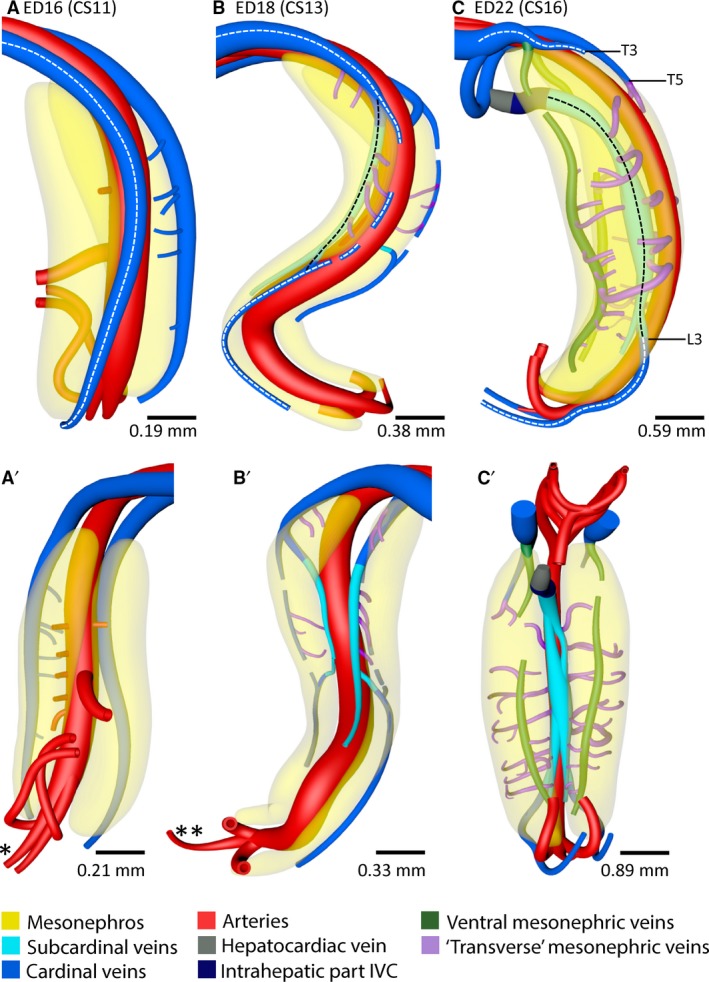

Figure 3.

Inferior caval vein develops from caudal part of caudal cardinal veins in rodents. Right‐sided (A–D) and corresponding ventral views (A’–D’) of vessels and relevant structures in mouse embryos between ED11 and ED14 (≈ CS13–CS19). The stippled white lines in (A–D) indicate the caudal cardinal veins that remodel during inferior caval and azygos vein development. The levels T12 (B,C) and L3 (D) identify relocation of the caudal cardinal veins from a dorsolateral to a ventrolateral position relative to the aorta. Arrowhead (C) – interruption area of the right caudal cardinal vein; SMA – superior mesenteric artery. The vertebral levels T2 (A), T3 (B), T7 (C) and T12 (D) indicate (regression of) the cranial mesonephric border. A colour code identifies the venous systems and structures shown.

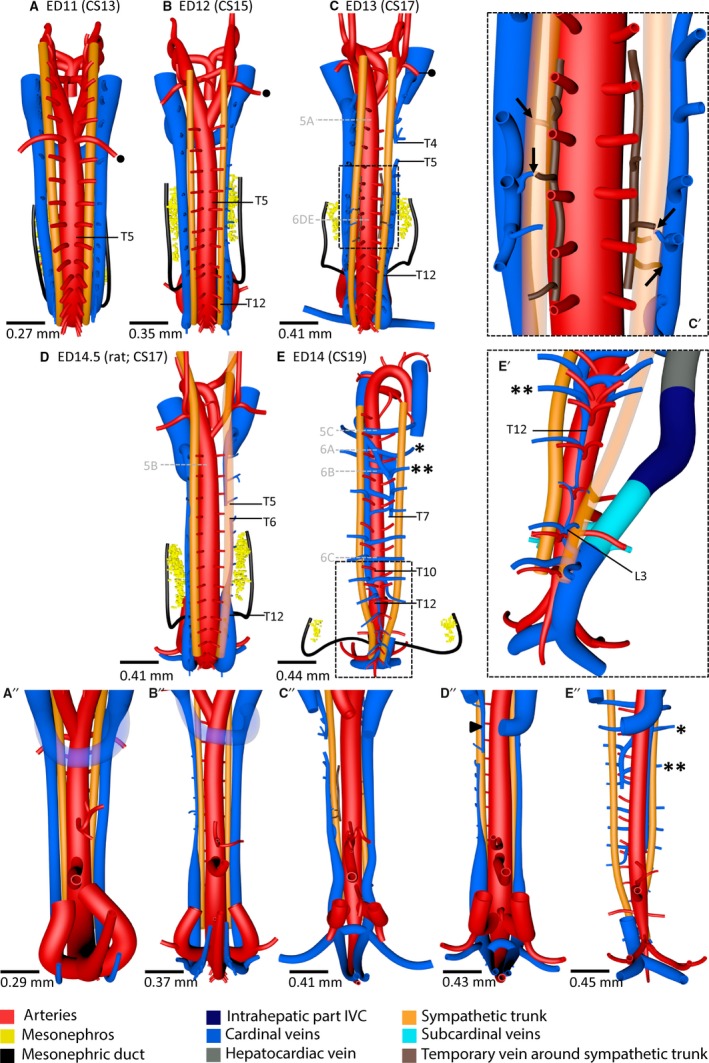

Figure 4.

Azygos vein develops from cranial part of caudal cardinal veins in rodents. (A–E) (dorsal views) and (A”–E”) (corresponding ventral views) show that the position of the caudal cardinal veins changed from dorsolateral with regard to the sympathetic trunk at ED11 to ventromedial at ED14. The ED14.5 rat embryo (D,D”) shows an intermediate stage of this process where the cardinal vein cranial to the right‐sided interruption has already undergone migration (arrowhead in D”). The diameter of the right‐sided caudal cardinal vein had decreased at ED12 (B,B”) and was interrupted between T4 and T5 at ED13 (C,C”). To accommodate sufficient drainage of the dorsal body wall by the intersegmental veins, a temporary network (brown) developed medial to the sympathetic trunk in the lower thoracic region at ED13 and formed anastomoses with the azygos venous system and/or intersegmental veins (C'; indicated by arrows in magnification of square in C). In (E), (E', magnification of square in E) and (E”), one asterisk indicates intersegmental veins positioned cranial to T5 and a double asterisk those positioned at T5 or caudal to it. Note in (E') the confluence of the left cardinal vein (future azygos vein) with the common stem of the intersegmental veins at level L3. Black dot – subclavian artery; grey letters 5A–C and 6A–E in (C–E) – levels of the corresponding histological sections in Figs 5 and 6, respectively. A colour code identifies the venous systems and structures shown.

Subcardinal vein development

At ED11, vascular sprouts branched off ventrally from both caudal cardinal veins between T5 and T12, and formed a venous network between the aorta and urogenital fold (Figs 2 and 3A,A’). At ED12, this network started to form longitudinal channels, the ‘subcardinal’ veins, along the ventromedial border of the urogenital fold and ventrolateral to the aorta (Figs 2 and 3B,B’). Furthermore, a cardinal‐subcardinal anastomosis at the level of T10 developed as the main flow route, whereas more cranial and caudal anastomoses disappeared (Figs 2 and 3B). This cardinal‐subcardinal anastomosis became located at the level of T12 at ED13 and at the level of L3 at ED14 (Fig. 3C,D). The intrahepatic part of the inferior caval vein was still a sinusoidal network at ED12, but had formed a channel and merged with the right subcardinal vein at ED13 (≈ CS17; Figs 2 and 3C,C’). Furthermore, after ED13, anastomoses developed between the left and right subcardinal veins, just caudal to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and merged to establish one main intersubcardinal anastomosis (level L1) at ED14 (≈ CS19; Figs 2, 3D’ and S2D). At this stage, the left subcardinal vein had decreased in diameter and lost its left cardinal‐subcardinal anastomosis at the level of L3, so that it only drained the left kidney, adrenal and gonad.

Inferior caval vein development

The ‘prototype’ of the inferior caval vein developed between ED12 and ED13, when a straight channel through the liver formed from the hepatic sinusoids (Figs 2 and 3C). The uppermost part of the inferior caval vein, the so‐called hepatocardiac vein, had already developed at ED11 from the remnant of the right vitelline vein between the liver and the heart. At the caudal‐most part of the caudal cardinal veins, one large intercardinal anastomosis formed ventral to the median sacral artery and just caudal to the bifurcation of the aorta between ED12 and ED13 (Figs 2 and 3C’). This anastomosis connected the iliac veins with the right‐sided caudal cardinal vein (infrarenal part of inferior caval vein) at the level of L5 at ED14 (Fig. 3D’), whereas the left‐sided caudal cardinal vein became involved in azygos vein development between ED13 and ED14.

Azygos vein development

Cranial to L3, the remnants of the caudal cardinal veins that were still present at ED14, evolved into the azygos venous system. On the right side, the caudal cardinal vein became interrupted between T4 and T5 on ED13. Multiple interruptions down to L3 were observed at ED14 (Fig. 4C,E). Furthermore, the right cardinal vein lost its connection with the right common cardinal vein at ED14 (Figs 2 and 4E). The left‐sided caudal cardinal vein remained intact down to L3, but decreased in diameter and its position changed from lateral to medial of the sympathetic trunk between ED13 and ED14. The portion of the caudal cardinal vein between T12 and L3 had even relocated dorsomedially relative to the aorta (Fig. 4E,E’), as the sympathetic trunk had acquired a more medial position in that region. The common stem of both intersegmental arteries from the aorta (Fig. 4E’) also showed that left‐ and right‐sided dorsal structures had approached each other at this level. The right caudal cardinal vein began to form anastomoses along its entire length with the left cardinal vein (azygos vein) dorsal to the aorta and itself became more fragmented (hemi‐azygos vein).

Our collection of mouse embryos did not contain specimens in which the caudal cardinal veins occupied an intermediate position between their lateral position relative to the sympathetic trunk at ED13 and their medial position at ED14 (Figs 4C,E and 5A,C). However, such an intermediate stage with the caudal cardinal veins ventral to the sympathetic trunk was found in ED14.5 rat embryos (Figs 4D and 5B). The asymmetry in diameter between the left and right caudal cardinal veins and the right‐sided interruption (in the rat at T5–T6) were similar between these ED14.5 rat embryos and the corresponding ED13 mouse embryos (Fig. 4C,D). The right cardinal vein cranial to T5 and the left cardinal vein between T2 and T12 showed a ventral and ventrolateral position, respectively, relative to the sympathetic trunk in these rat embryos (Fig. 4D,D”).

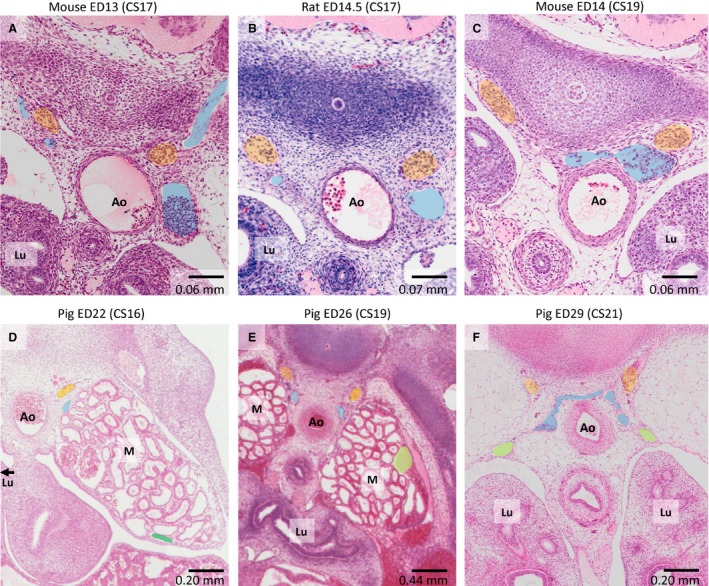

Figure 5.

Histology of gradual change in position of caudal cardinal veins relative to sympathetic trunk. (A–C) Latero‐medial relocation of veins relative to the sympathetic trunk (orange) in rodents between ≈ CS17 and ≈ CS19. (D–F) The same relocation for pig embryos between ≈ CS16 and ≈ CS21. Ao – aorta; Lu – lung; M – mesonephros; blue – caudal cardinal veins; dark green – ventral mesonephric vein; light green – lateral mesonephric vein.

In the mouse all intersegmental veins passed the sympathetic trunk laterally before draining into the caudal cardinal veins up to ED13. On ED14, intersegmental veins still passed the sympathetic trunk laterally cranial to T5 [Figs 4E,E” (asterisk) and 6A], but now passed the trunk medially between T5 and L5 [Figs 4E,E’,E” (double asterisk) and 6B,C]. A small venous network lateral to the intersegmental arteries and medial to the sympathetic trunk had developed over four segments (T7–T11) at ED13 (≈ CS17; Figs 2, 4C,C’ and 6D,E) and had extended in caudal direction up to L5 at ED13.5 (≈ CS18). The network developed small anastomoses with the caudal cardinal veins medial to the sympathetic trunk [Figs 2, 4C’ (arrows) and 6D,E]. The intersegmental veins drained into the caudal cardinal veins both directly and via the newly formed network (Fig. 4C’). No anastomoses between the left and right sides of this venous network were found.

Figure 6.

Histology of intersegmental vein rearrangement. (A–C) Position of the intersegmental veins relative to the sympathetic trunk (orange) at the levels of T4, T5 and T9 in an ED14 (≈ CS19) mouse embryo. (F–H) Comparable configuration in the human embryo at CS19. (D,E) Network (brown) formation around the sympathetic trunk anastomosing with the azygos system (cardinal veins) and/or intersegmental veins. Ao – aorta; Lu – lung; Ad – adrenal gland; blue – azygos system with accompanying intersegmental veins.

We deduced from the re‐arrangement of the position of the intersegmental veins from lateral to medial relative to the sympathetic trunk between ED13 and ED14 (Fig. 4C,E) that the capillary network was a temporary ‘footprint’ of this shift in venous blood drainage. In agreement, the network configuration was no longer found at ED16 and was replaced by medial passage of intersegmental veins en route to the cardinal vein. These findings prompted us to search for a similar rearrangement of the intersegmental veins in human embryos. In agreement with rodent development, a CS19 human embryo (S9325, Carnegie collection) showed lateral passage of the intersegmental veins to the caudal cardinal vein cranial to T5 and medial passage caudal to T5, and the intersegmental veins even passed through the sympathetic trunk at T5 (Fig. 6F–H). The findings in human embryos, therefore, also favour a gradual shift in position of the caudal cardinal veins from lateral via ventral to medial relative to the sympathetic trunk while transforming into the azygos venous system.

Infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos vein development in the pig

A pictorial abstract of the development of the infrahepatic caval and azygos veins in pig embryos is shown in Fig. 7. Our reconstructed 3D models can be interactively examined in Supporting Information Fig. S3.

Figure 7.

Pictorial abstract of infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos vein development in pigs. Ventral views. A colour code identifies the respective venous systems. The gradient from light to dark blue depicts the caudal extension of the caudal cardinal veins with time. Venous branches (‘transverse’ mesonephric veins) within the urogenital fold and along the mesonephric tubules are indicated in purple with vessels dorsal (without fill) and ventral (filled) in the mesonephroi indicated separately.

Inferior caval vein development

In pig embryos of ED16 (≈ CS11) and ED17 (≈ CS12), both caudal cardinal veins continued from the common cardinal vein up to the level of the umbilical arteries, but did not as yet pass these arteries into the most caudal body region (Figs 8A,A’ and S3A). The curvature of the caudal cardinal veins followed that of the body axis. The dorsal aortae of these embryos had not yet merged in the caudal body region, but had done so at ED18 (≈ CS13) [Figs 8A’,B’ (asterisks) and S3B]. At ED18, the C‐shaped body axis seen at ED16 and ED17 transformed temporarily into a helical shape (cf. Figure 50 in Patten, 1948) and the caudal cardinal veins followed this change in shape (Fig. 8B). From ED21 (≈ CS15) onwards, the helical shape of the embryo uncoiled, so that the C‐shape configuration of the body axis was restored (Fig. 8C). At ED22 (≈ CS16), the caudal cardinal veins extended into the caudal‐most body region by crossing the umbilical arteries dorsally. Furthermore, the single cranio‐caudal C‐shape of the veins in the ED16 embryo became transformed into a triple C‐shape in the ED22 embryo. The cranial and middle C‐shapes developed concomitant with the dorsolateral expansion of the underlying lung and mesonephros, respectively, while the caudal C‐shape developed because the umbilical arteries became more prominent and expanded dorsolaterally due to the growth of the metanephroi (definitive kidneys) in between the umbilical arteries (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

Caudal extension and ventral outgrowth of caudal cardinal veins in the pig. Right‐sided (A–C) and ventral views (A’–C’) of vessels and relevant structures in pig embryos between ED16 and ED22 (≈ CS11–CS16). (A–C) Stippled white lines indicate the caudal cardinal veins that remodel during inferior caval and azygos vein development. (B,C) Black stippled lines indicate the route of the blood flow along the medial mesonephric border. (C) Area of complete caudal cardinal vein regression is indicated between T3 and L3 on the left side and between T5 and L3 on the right side. Furthermore, level L3 indicates the cardinal‐subcardinal anastomosis coursing from dorso‐ to ventro‐lateral relative the aorta. Ventrolateral, ventromedial and dorsal branches (purple: ‘transverse’ mesonephric veins) that course within the urogenital fold and along the mesonephric tubules all followed a course in the transverse plane, that is, perpendicular to the ventral mesonephric veins. *No merged aorta; **merged aorta. A colour code identifies the venous systems and structures shown.

The caudal cardinal veins were positioned dorsolateral to the aorta and dorsal to the mesonephroi, which occupied the urogenital fold. At ED16, small branches were seen to extend ventrolaterally from the right caudal cardinal vein into the mesonephros (Fig. 8A). At ED17, such branches also extended from the left caudal cardinal vein. At ED18, these small veins extended along the mesonephric tubules towards the ventromedial border of the mesonephros, where they merged to form a longitudinal channel, the subcardinal vein (Figs 7 and 8B,B’). The cranial ends of the left and right subcardinal veins drained into the corresponding caudal cardinal vein via an anastomosis along the medial mesonephric border at ED18. Meanwhile, major changes were observed in the caudal cardinal veins. At ED18, the caudal cardinal veins became interrupted at several locations in the middle body region (Figs 7 and 8B), so that these veins only persisted cranial to T3 on the left side and T5 on the right side, and caudal to L3 on both sides at ED22 (Figs 7, 8C and 9C). The venous return to the heart, therefore, changed from dorsal to ventromedial to the mesonephroi. Intersubcardinal anastomoses developed at ED21 (≈ CS15; Fig. 7) and had become a single, large anastomosis ventral to the aorta between T9 and L1 at ED26 (≈ CS19; Fig. 9A). Furthermore, the cranial subcardinal‐to‐cardinal connections were lost at ED21, after the right subcardinal vein had become continuous with the intrahepatic portion of the future inferior caval vein (Figs 7 and 8C,C’). Because the intrahepatic part of the inferior caval vein had also connected cranial to the remnant of the right vitelline vein (the hepatocardiac vein), the caudal cardinal‐subcardinal anastomoses at L3 on both sides had become the main conduits of blood to the heart (Figs 8C and 9A,B).

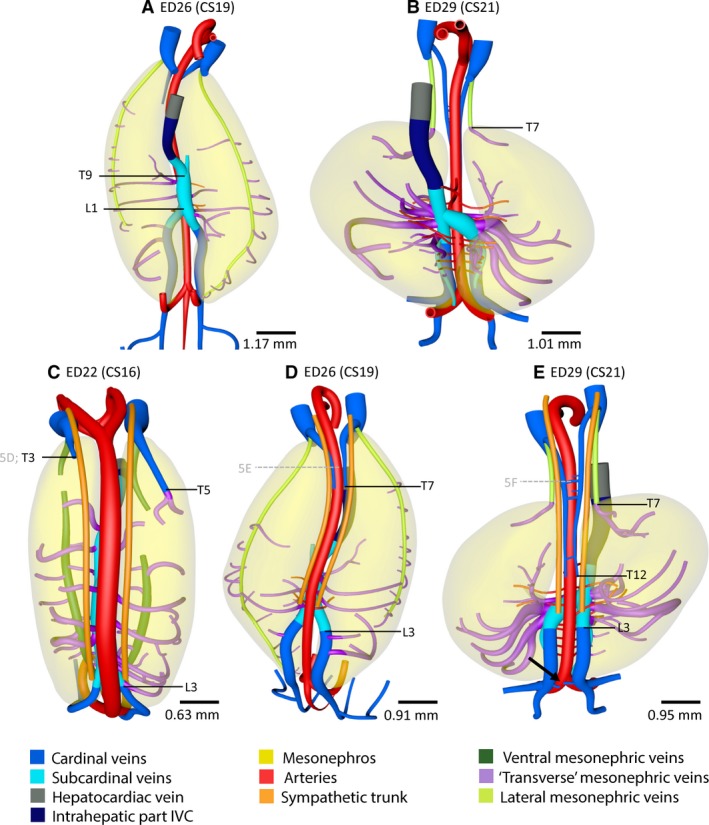

Figure 9.

Inferior caval and azygos vein development in the pig. Ventral (A,B) and dorsal views (C–E) of vessels and relevant structures of pig embryos between ED22 and ED29 (≈ CS16–CS21). Vertebral levels T9 to L1 (A) indicate the position of the subcardinal anastomosis. (B,E) The level of T7 indicates the caudal end of the lateral mesonephric vein which corresponds to the cranial border of the mesonephros. Note that the number of mesonephric arteries doubled at ≈ CS21 (B) compared with ≈CS19 (A). Furthermore, vertebral levels T3–L3 on the left and T5–L3 on the right side in (C), levels T7–L3 in (D) and levels T12–L3 in panel E indicate the interrupted part of the caudal cardinal veins. (C–E) Grey letters 5D–F in vertebral levels of the histological sections in Fig. 5. Ventrolateral, ventromedial and dorsal branches (purple: ‘transverse’ mesonephric veins) that course within the urogenital fold and along the mesonephric tubules all followed a course in the transverse plane, that is, perpendicular to the ventral or lateral mesonephric veins. A colour code identifies the venous systems and structures shown.

At ED26 (≈ CS19), the cranial part of the caudal cardinal veins had extended to T7 (Fig. 9D). The caudal part of the caudal cardinal veins acquired a more medial position relative to the mesonephros and first a more dorsal (ED22; ≈CS16) and then, at ED26, also a more medial position relative to the developing metanephroi. This mutual approximation of structures close to the midline was also visible in the merged stems of both intersegmental arteries at ≈ CS19. Mesonephros regression was rapid between the initiation of the development of a caudal intercardinal anastomosis in the iliac region at ED29 [≈CS21; Figs 1A (pig), 7 and 9E (arrow)] and its completion at ED33 (≈ CS23; Fig. 7). Thereafter, the left caudal part of the caudal cardinal veins started to regress and had disappeared at ~ 36 mm crown‐rump length (CRL; 8 weeks of development). By then, the definitive architecture of the inferior caval vein had been established.

The mesonephric veins

Ventral mesonephric vein

As the mesonephros increased in size, additional veins appeared. The so‐called ventral mesonephric veins (Butler, 1927) appeared on the medial side of the mesonephric duct, that is, ventromedially within the urogenital fold just underneath the subperitoneal fascia (Fig. 10A’). These ventral veins extended almost along the entire length of the mesonephroi and drained into the cranial part of the caudal cardinal veins (Figs 7 and 10A,A’). Caudally, no connection with the caudal cardinal or subcardinal veins was observed. At ED21, these veins were still interrupted at several locations, but only a small left‐sided interruption at the level of T5 and a right‐sided interruption between T6 and T8 were still present at ED22 (≈ CS16). Ventrolateral branches around the mesonephric tubules drained into the ventral mesonephric vein (Fig. 1D), whereas some of the ventromedial branches connected this vein to the subcardinal veins. Additional venous branches developed dorsally and coursed towards the subcardinal veins (Fig. 1D). Of note, the ventrolateral, ventromedial and dorsal branches all followed a course in the transverse plane, that is, perpendicular to the large mesonephric veins.

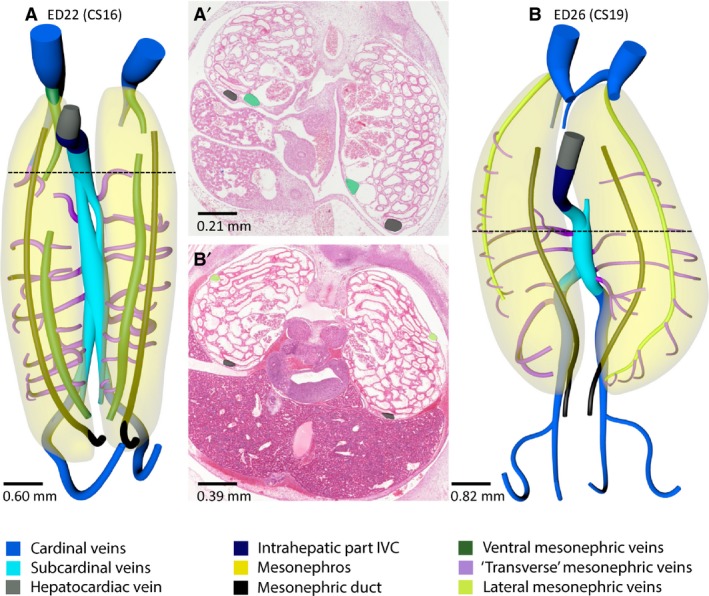

Figure 10.

Ventral and lateral mesonephric veins in the pig. Ventral views (A,B) and histological sections (A' and B' taken at the level indicated by a black stippled line in A and B) of vessels and relevant structures of pig embryos at ED22 (≈ CS16) and ED26 (≈ CS19). The ventral mesonephric veins (dark green in A,A') had appeared at ED22 as an almost continuous longitudinal channel that drained into the cranial part of the caudal cardinal veins. The lateral mesonephric veins (light green in B,B') appeared at ED26. The ventral mesonephric veins were positioned just medial (A') to the mesonephric duct (black), whereas the lateral mesonephric veins were located dorsolaterally (B'). The cranial portion of the ventral and lateral mesonephric veins may be common. A colour code identifies the venous systems and structures shown.

Lateral mesonephric vein

The ventral mesonephric vein had disappeared in ED26 (≈ CS19) embryos. Meanwhile, another vein developed from collaterals dorsolateral to the mesonephric duct, that is, laterally within the urogenital fold just underneath the subperitoneal fascia (Figs 7 and 10B,B’). The so‐called lateral mesonephric veins (Butler, 1927) connected cranially to the caudal cardinal veins as the ventral veins had done earlier. Furthermore, the left lateral mesonephric vein connected caudally to the left caudal cardinal vein. The left and right lateral mesonephric vein both connected to respectively the left and right caudal part of the caudal cardinal vein at ED28 (≈ CS20). From ED26 onwards, ventrolateral branches around mesonephric tubules drained into the lateral mesonephric vein, whereas most dorsal branches drained into the subcardinal vein.

The azygos venous system

At ED26 (≈ CS19), the cranial part of the caudal cardinal veins extended caudally as far as T7 only (Fig. 9D). Its position had changed from lateral to medial relative to the sympathetic trunk between ED22 (≈ CS16) and ED29 (≈ CS21) (Figs 5D–F and 9C–E). No other developing venous system was observed in the thoracic region during this time period. Between ED26 and ED29, the cranial part of the caudal cardinal veins extended to T12 and formed several intercardinal anastomoses dorsal to the aorta (Fig. 9E). Furthermore, the right cardinal vein lost its connection with the right common cardinal vein at ED31 (≈ CS22), thereby establishing a left‐sided azygos venous system. At ED29, the lateral mesonephric veins had disappeared completely within the urogenital fold, but persisted temporarily cranial to T7, that is, cranial to the mesonephros and still drained cranial branches from the mesonephroi (Figs 5F, 7 and 9B,E). By ED31 (≈ CS22), the lateral mesonephric veins had disappeared completely.

Discussion

The body plan of the caudal veins is similar in mammalian species

The infrarenal part of the inferior caval vein developed from the right caudal cardinal vein, the renal part of the inferior caval vein from the subcardinal veins, and the azygos venous system from the cranial remnants of the caudal cardinal veins. As the subcardinal veins developed as a network sprouting from the caudal cardinal veins, the infrahepatic caval and azygos veins developed from the caudal cardinal veins only, irrespective of the degree of mesonephros development. However, there were some differences in the timing of critical events in inferior caval and azygos vein development between the mammalian species we studied. These apparently heterochronous aspects of caudal vein development appeared to be necessary to allow for proper joining of preferential conduits for venous return and suggested that at least part of the observed changes was adaptive to changes elsewhere in the system.

Extensions of the caudal cardinal veins

Ventral outgrowth of the caudal cardinal veins

In human embryos, small branches sprouting from the caudal cardinal veins that traversed the mesonephros appeared at CS15, whereas such branches were already seen in pig embryos at ≈ CS11. This venous plexus was first described by Hochstetter (1893) and was coined the ‘subcardinal’ venous system by Lewis (1902). We retained the term ‘subcardinal’ (Hikspoors et al. 2015) because these veins, once formed, drain the mesonephric tubules, whereas the afferent veins reportedly derive from the caudal cardinal veins proper (Butler, 1927; Vollmerhaus et al. 2004). The subcardinal veins were present along the entire length of the mesonephroi in pig embryos, but only in its caudal half in human embryos (Hikspoors et al. 2015). The absence of this network in the cranial part of the human mesonephros suggests that it is an early marker of upcoming mesonephric regression (Fig. 1A). The subcardinal network around mesonephric tubules does not develop in rodents, presumably because these tubules are not functional or less so than those in species with mesonephric glomeruli. It is tempting to speculate that the absence of this network causes the relatively short lifetime of mesonephric tubuli in rodent embryos.

Caudal outgrowth of the caudal cardinal veins

In accordance with Gladstone (1929), Cornillie et al. (2008a,b) and our earlier study (Hikspoors et al. 2015), we observed extension of the caudal cardinal veins into the most caudal body region at CS13–14 in all species studied. Furthermore, the dorsolateral course of the caudal cardinal veins relative to the umbilical arteries was similar. There is, therefore, no need to invoke the development of a new venous system (the ‘sacrocardinal veins’; Grunwald, 1938) to account for the presence of veins beyond the umbilical arteries.

Developmental changes in the mesonephros and its perfusion

Mesonephric size

The mesonephros develops within the urogenital fold from the axilla to the groin in rodent, human and pig embryos. The rodent mesonephros is never present along the entire urogenital fold, but temporarily extends caudally and regresses cranially (Fig. 1A). The rodent and human mesonephroi are similar in that their cranial regression begins early, whereas cranial regression begins later in the pig embryo (≈ CS19 vs. CS15). The mesonephros of sheep and rabbits has a similar regression pattern as that of pigs, whereas that of cats is considered large but has a similar regression pattern as the human mesonephros (Bremer, 1916; Tiedemann, 1976). The functional implications of these interspecies differences in mesonephric development for placental development have been discussed extensively (Bremer, 1916; Leeson & Baxter, 1957; Stanier, 1960; Moritz & Wintour, 1999; Tiedemann, 1976) but we considered the arguments tenuous and found, instead, that the degree of mesonephric development corresponded inversely with the growth rate of the embryo and the capacity for amino‐acid catabolism and gluconeogenesis (Dingemanse & Lamers, 1994). Irrespective of functional interpretations, a large mesonephros with well‐developed tubules requires an extensive venous network around these tubules. In agreement, both Butler (1927) and we found fair‐sized ventral and lateral mesonephric veins in the mesonephros of sheep and pigs. However, Butler's claim that development of supracardinal veins is necessary to accommodate drainage of the dorsal body wall in species with a mesonephros with glomeruli could not be substantiated.

Mesonephric veins and portal perfusion

Although it is generally believed that the caudal cardinal veins are the supplying vessels and the subcardinal veins are the draining vessels of the mesonephric tubules (Butler, 1927; Vollmerhaus et al. 2004), we found little structural evidence for a portal perfusion of the mesonephros in our embryos. The explanation may be found in the contribution of the mesonephric arteries to mesonephric perfusion. In the (mesonephric) kidneys of amphibians and reptiles, there is, in addition to the venous supply, a substantial contribution of arterial blood that perfuses the glomeruli (http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/V/VertebrateKidneys.html; Morris & Campbell, 1978). In this respect it is of interest that mammalian species without mesonephric glomeruli (rodents) do not develop a venous network around their mesonephric tubules (it bypasses the mesonephros medially). In species with mesonephroi that do contain glomeruli we found bilaterally approximately four well‐developed mesonephric arteries up to CS19 (humans, pigs), and eight arteries thereafter in pig embryos (Fig. 9; see also Tiedemann & Egerer, 1984), and sheep embryos (Davies, 1950). These arteries branched off at the lateral sides of the aorta just below the level of the superior mesenteric artery. Based on these findings, we posit the mesonephric arteries represent an important afferent blood supply in mammalian embryos and that the mesonephric veins we have reconstructed are efferent rather than afferent vessels. In line with this hypothesis, we found that the well‐developed longitudinal veins on the surface of the pig mesonephroi (Cornillie et al. 2008a,b) drained into the caudal cardinal veins at the cranial end of the mesonephros and via multiple small intertubular branches, into the subcardinal veins. While the ventral mesonephric vein regressed caudally, it became connected cranially to the newly formed lateral mesonephric vein (≈ CS19–CS20). Like the changing position of the mesonephric duct relative to the mesonephros, the replacement of the ventral mesonephric vein by the lateral mesonephric vein probably reflects the dorsolateral expansion of the mesonephros. These interpretations contrast with those of Butler (1927), who described that the ventral and lateral mesonephric veins had a direct contact with the caudal cardinal veins at the caudal border of the mesonephroi, that is, functioned as the afferent veins of the mesonephros.

Changes in topography of the caudal cardinal veins

The caudal cardinal veins developed three C‐shaped segments: the cranial and middle segments assumed a C‐shape concomitant with the expansion of the underlying lung and mesonephros, respectively, while the caudal C‐shape appeared to reflect the increase in diameter of the umbilical arteries. The vessel also acquired a more dorsolateral position, which corresponded with growth of the metanephroi in between the umbilical arteries. Butler (1927) and Gladstone (1929) claimed, instead, that the formation of a new system on the medial side of the metanephroi, the ‘supracardinal’, or ‘lateral sympathetic line’ veins, was necessary to compensate for the regression of the corresponding part of the caudal cardinal vein in mammals with a functional mesonephros. In mice, the caudal cardinal veins are positioned medial to the metanephroi throughout development, possibly because of their small mesonephros, and would ‘therefore’ persist (Butler, 1927). However, we found, in agreement with Hochstetter (1893), Cornillie et al. (2008a,b) and Hikspoors et al. (2015), that the caudal part of the caudal cardinal veins does not disappear in pig and human embryos, but changes in position from lateral to medial relative to the metanephroi due to the dorsolateral expansion of these kidneys. The dorsal position of the caudal cardinal veins relative to the mesonephros did not change.

Remodelling of intersegmental veins due to changing position of caudal cardinal veins

There is general agreement that the azygos venous system between T4 and its drainage into the superior caval vein develops from the caudal cardinal veins, with tributary intersegmental veins that pass the sympathetic trunk laterally (Reagan, 1919; Huntington & Mc Clure, 1920; Auer, 1946; Butler, 1950; Halpern, 1953). What happens caudal to T4 is more controversial. Most investigators argue that the presence of intersegmental veins that pass the sympathetic trunk medially requires the development of perisympathetic venous collaterals (the supracardinal or medial sympathetic line veins; Huntington & Mc Clure, 1920; Mc Clure & Butler, 1925; Reagan & Robinson, 1926; Butler, 1927; Gladstone, 1929; Cornillie et al. 2008b). We agree with the description, but not the explanation. We interpret the presence of a small venous network on the medial border of, or even traversing the sympathetic trunk caudal to, T4 as reflecting the formation of collaterals due to disturbance of the venous return through the intersegmental veins during the lateral‐to‐medial change in position of the caudal cardinal veins. We have interpreted this ‘displacement’ of the caudal cardinal veins to occur as a result of underlying organ expansion. In rodent embryos, this lateral‐to‐medial switch in intersegmental drainage occurs during ≈ CS17–CS19. It should be emphasized that the left caudal cardinal vein remains intact in rodent embryos during these stages, which makes regression and re‐building of this vessel all the more unlikely. Furthermore, our finding that small veins pass through the sympathetic trunk in human embryos at CS19 also argues strongly in favour of collaterals rather than the development of a new vessel. The lateral‐to‐medial displacement of the caudal cardinal veins was already described by Hochstetter (1893).

Interruption of the caudal cardinal veins and development of intercardinal anastomoses

Interruption of the caudal cardinal veins

Intersubcardinal anastomoses developed at CS16 in human and pig embryos, and at ≈ CS18 in mouse embryos. The late development of intersubcardinal anastomoses in mouse embryos correlates with the long persistence of the left‐sided caudal cardinal vein to ≈ CS19 and, hence, the persisting capacity to drain that part of the body via the ‘dorsal’ route. The right‐sided subcardinal vein drained into the capillary network of the liver at ≈CS16 in mouse and pig embryos, and only after CS18 in the human embryo (Hikspoors et al. 2015). In mice, the right caudal cardinal vein becomes interrupted earlier (≈ CS17; ED13), while caudal cardinal vein interruptions were seen very early in pig embryos (≈ CS13; ED18). Therefore, early development of the ‘ventral’ route is necessary in pig and mouse embryos to ensure sufficient drainage as long as iliac intercardinal anastomoses have not yet formed.

Inter‐cardinal anastomoses

Iliac region. The iliac intercardinal anastomoses just caudal to the umbilical arteries first appeared in human embryos (CS15) and only later in sheep (≈ CS19; ED28) (Butler, 1927) and pig embryos (≈ CS21, ED29), with rodents taking an intermediate position (≈CS17, ED13). In human and pig embryos, the first appearance of these anastomoses coincided with mesonephric regression. In mouse embryos with rudimentary mesonephroi, the caudal cardinal vein on the left side persisted relatively long and the caudal cardinal vein‐subcardinal vein‐liver conduit on the right side was established earlier than in the human. Only after establishment of the iliac intercardinal anastomosis and the renal intersubcardinal anastomosis, did the caudal part of the left caudal cardinal vein start to regress (mouse; ≈ CS18, human; CS20 and pig; ≈ CS22) and the right‐sided infrarenal inferior caval vein become established.

Thoracic region. Lung growth (Auer, 1946; Hikspoors et al. 2015) moved the cranial part of the caudal cardinal veins from lateral to medial relative to the sympathetic trunk at CS18–19 in the species studied. Inter‐cardinal anastomoses also developed at similar time points (mouse: ≈ CS19, human: CS20, pig: ≈ CS21). The intercardinal anastomosis that develops between the cranial cardinal veins forms the so‐called brachiocephalic vein at CS21–22 in human and pig embryos, whereas this anastomosis does not develop in mice. The eventual fate of the azygos systems is very variable: in mouse and pig embryos the main vessel (azygos vein) forms on the left side, whereas it forms on the right side in human embryos. In pig embryos, the main azygos vein regresses in the fetal period, whereas the smaller hemiazygos vein persists (Reagan, 1919; Patten, 1948). Apparently, there is no relation between the forming of a brachiocephalic vein and the sidedness or persistence of the azygos system.

Conclusion

The changing architecture of the caudal venous system during development of the inferior caval and azygos veins is similar in the species studied except for differences necessary to accommodate the different degree of mesonephros development. Striking features in pig embryos with a very large mesonephros were early interruptions of the cardinal veins, temporary development of ventral and lateral mesonephric veins inside the large mesonephroi, and very late development of the iliac intercardinal anastomosis. In mouse embryos with a rudimentary mesonephros (no glomeruli), the left caudal cardinal vein persisted relatively long and the venous plexus around the sympathetic trunks clearly identified changes in the course of the intersegmental veins rather than the establishment of a new venous system. Despite these examples of heterochronic development that appear to accommodate differences in mesonephric size and function, the overall developmental pattern was remarkably similar. In fact, it does not require many assumptions to extend our model of inferior caval vein development to that of species for which descriptions are available but that we did not study (e.g. cat, rabbit and sheep; Huntington & Mc Clure, 1920; Butler, 1927), because our main criticism of the existing literature is that changes in topography were interpreted as the appearance of new venous systems rather than as adaptations to changing venous blood flow patterns that, in all likelihood, result from growth of the embryo. Even development in marsupials appears to be similar, with the subcardinal veins developing as ventromedial divisions of the caudal cardinal veins and the ‘supracardinal’ veins as collaterals around the caudal cardinal veins, albeit along a much longer distance than in mammals (McClure, 1906; Tribe, 1924). If correct, our model for inferior caval and azygos vein development in mammals should, therefore, replace the complex models present in nearly all textbooks.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Quality check of image transformation from amira 3D to cinema 4D. (A) The amira 3D output in which individual sections used for reconstruction are still visible. (B) Simultaneous visualization of the amira 3D output (light blue) and the remodelled cinema 4D image (colours similar to Figs 8, 9, 10). (C) Smoothened cinema 4D model without noise from individual sections.

Fig. S2. Three‐dimensional PDF of inferior caval and azygos vein development in the mouse between ED11 and ED14. Open the PDF‐file. The 3D PDF becomes activated after ‘clicking’ with the mouse on the embryo. A toolbar appears at the top of the screen that includes the option ‘model tree’. The model tree displays a material list of structures in the upper box and preset viewing options in the lower box. The list of visible structures can be modified by marking or unmarking a structure. Furthermore, a structure can be rendered transparent by selecting that option from the drop‐down menu after selecting the structure with the right mouse button. The cameras indicate preset positions of right‐sided, dorsal or ventral views of the embryo. To manipulate the reconstruction, press the left mouse button to rotate it, the scroll button to zoom in or out, and the left and right mouse buttons simultaneously to move the embryo across the screen. The slicer button in the toolbar allows cross sections to be done. The plane of section can be adjusted with the off‐set and tilt options. The colour code is identical to that in Figs 3 and 4 and all structures are listed by name in the ‘model tree’. Note that the 3D PDF can be opened on any computer as long as it contains an Adobe PDF reader.

Fig. S3. Three‐dimensional PDF of inferior caval and azygos vein development in the pig between ED16 and ED29. Manual of the interactive 3D PDF is identical to that of Fig. S2. The colour code is identical to that in Figs 8 and 9, and all structures are listed by name in the ‘model tree’.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Maurice van den Hoff (AMC) for allowing us to use the AMC series of mouse and rat embryos. Special thank goes to Els Terwindt (MU) for her technical assistance. The financial support of ‘Stichting Rijp’ is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Auer J (1946) Migration processes during ontogeny with reference to the venous development in the dorsal body wall. J Anat 80, 61–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer JL (1916) The interrelations of the mesonephros, kidney and placenta in different classes of animals. Am J Anat 19, 179–209. [Google Scholar]

- Butler EG (1927) The relative role played by embryonic veins in the development of the mammalian vena cava posterior. Am J Anat 39, 267–353. [Google Scholar]

- Butler H (1950) The development of the azygos veins in the albino rat. J Anat 84, 83–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler H, Juurlink BHJ (1987) An atlas for staging mammalian and chick embryos. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornillie P, Simoens P (2005) Prenatal development of the caudal vena cava in mammals: review of the different theories with special reference to the dog. Anat Histol Embryol 34, 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornillie P, Van Den Broeck W, Simoens P (2008a) Three‐dimensional reconstruction of the remodeling of the systemic vasculature in early pig embryos. Microsc Res Tech 71, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornillie P, Van Den Broeck W, Simoens P (2008b) Origin of the infrarenal part of the caudal vena cava in the pig. Anat Histol Embryol 37, 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J (1950) The blood supply of the mesonephros of the sheep. Proc Zool Soc Lond 120, 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse MA, Lamers WH (1994) Expression patterns of ammonia‐metabolizing enzymes in the liver, mesonephros, and gut of human embryos and their possible implications. Anat Rec 238, 480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans HE, Sack WO (1973) Prenatal development of domestic and laboratory mammals: growth curves, external features and selected references. Anat Histol Embryol 2, 11–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone R (1929) Development of the inferior vena cava in the light of recent research, with especial reference to certain abnormatilities, and current descriptions of the ascending lumbar and azygos veins. J Anat 64, 70–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald P (1938) Die Entwicklung der Vena cava caudalis beim Menschen. Mikroskop‐anat Forsch 43, 275–331. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern MH (1953) The azygos vein system in the rat. Anat Rec 116, 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikspoors JP, Soffers JH, Mekonen HK, et al. (2015) Development of the human infrahepatic inferior caval and azygos venous systems. J Anat 226, 113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstetter F (1893) Beitrage zur Entwickelung des Venensystems der Amnioten. Sauger. Gegenbaurs Morphol Jahrb 20, 543–648. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington GS, Mc Clure CFW (1920) The development of the veins in the domestic cat with special reference, 1) to the share taken by the supracardinal veins in the development of the postcava and azygos veins and 2) to the interpretation of the variant conditions of the postcava and its tributaries, as found in the adult. Anat Rec 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leeson TS, Baxter JS (1957) The correlation of structure and function in the mesonephros and metanephros of the rabbit. J Anat 91, 383–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis FT (1902) The development of the vena cava inferior. Am J Anat 1, 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Clure CFW (1906) A contribution to the anatomy and development of the venous system of didelphys marsupialis (L). Part II, development. Am J Anat 5, 163–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Clure CFW, Butler EG (1925) The development of the posterior vena cava inferior in man. Am J Anat 35, 331–383. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz KM, Wintour EM (1999) Functional development of the meso‐ and metanephros. Ped Nephrol 13, 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JL, Campbell G (1978) Renal vascular anatomy of the toad (Bufo marinus). Cell Tissue Res 189, 501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rahilly R, Müller F (2010) Developmental stages in human embryos: revised and new measurements. Cells Tissues Organs 192, 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten BM (1948) Embryology of the Pig. New York: McGraw‐Hill Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Reagan FP (1919) On the later development of the azygos veins of swine. Anat Rec 17, 110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Reagan FP, Robinson A (1926) The later development of the inferior vena cava in man and carnivora. J Anat 61, 482–484. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BF, Norton S (1979) Equivalent ages in rat, mouse and chick embryos. Teratology 19, 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanier MW (1960) The function of the mammalian mesonephros. J Physiol 151, 472–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler K (1989) The House Mouse: Atlas of Embryonic Development. New York: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann K (1976) The mesonephros of cat and sheep; comparative morphological and histochemical studies. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 52, 7–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann K, Egerer G (1984) Vascularization and glomerular ultrastructure in the pig mesonephros. Cell Tissue Res 238, 165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribe M (1924) The development of the hepatic venous system and the postcaval vein in the Marsupialia. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 212, 147–207. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmerhaus B, Reese S, Roos H (2004) The blood vessels of the mesonephros of domestic cattle (Bos taurus), a corrosion cast study. Anat Histol Embryol 33, 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Quality check of image transformation from amira 3D to cinema 4D. (A) The amira 3D output in which individual sections used for reconstruction are still visible. (B) Simultaneous visualization of the amira 3D output (light blue) and the remodelled cinema 4D image (colours similar to Figs 8, 9, 10). (C) Smoothened cinema 4D model without noise from individual sections.

Fig. S2. Three‐dimensional PDF of inferior caval and azygos vein development in the mouse between ED11 and ED14. Open the PDF‐file. The 3D PDF becomes activated after ‘clicking’ with the mouse on the embryo. A toolbar appears at the top of the screen that includes the option ‘model tree’. The model tree displays a material list of structures in the upper box and preset viewing options in the lower box. The list of visible structures can be modified by marking or unmarking a structure. Furthermore, a structure can be rendered transparent by selecting that option from the drop‐down menu after selecting the structure with the right mouse button. The cameras indicate preset positions of right‐sided, dorsal or ventral views of the embryo. To manipulate the reconstruction, press the left mouse button to rotate it, the scroll button to zoom in or out, and the left and right mouse buttons simultaneously to move the embryo across the screen. The slicer button in the toolbar allows cross sections to be done. The plane of section can be adjusted with the off‐set and tilt options. The colour code is identical to that in Figs 3 and 4 and all structures are listed by name in the ‘model tree’. Note that the 3D PDF can be opened on any computer as long as it contains an Adobe PDF reader.

Fig. S3. Three‐dimensional PDF of inferior caval and azygos vein development in the pig between ED16 and ED29. Manual of the interactive 3D PDF is identical to that of Fig. S2. The colour code is identical to that in Figs 8 and 9, and all structures are listed by name in the ‘model tree’.