Abstract

Background:

Airway management in large and retrosternal goiters with tracheal compression is often fraught with challenges and is a source of apprehension among anesthesiologists globally.

Aims:

In this study we attempt to delineate the preferred techniques of airway management of such cases in our institution and also to assess whether airway management was unnecessarily complicated.

Setting and Design:

Retrospective analysis.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review was conducted of thyroidectomies performed in our institution over a three year period from January 2013. Clinical, radiological, pathological, anesthetic and surgical data were obtained from hospital case records.

Statistical Analysis:

Qualitative data is represented as frequencies and percentages and quantitative data as mean and standard deviation.

Results:

Of 1861 thyroidectomies tracheal compression were present in 50 patients with minimum tracheal diameter ranging from 4-12mm (mean 7.84); with majority(95%) having a benign pathology. Critical tracheal compression (≤5 mm) was observed in four patients. Conventional intravenous induction and intubation under muscle relaxant was performed in majority (64%) of these patients. The rest of the cases (n=18) were intubated while preserving spontaneous ventilation after induction. Primary technique of airway management was reported successful in all cases with no instances of difficult ventilation or intubation. Postoperative morbidity in few cases resulted from hematoma (n=1), recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (n=1), tracheomalacia (n=1) and pulmonary complications (n=2).

Conclusion:

Airway management in patients with tracheal compression due to benign goiter is quite straightforward and can be managed in the conventional manner with little or no complications.

Keywords: Airway management, anesthesia, goiter, thyroidectomy, tracheomalacia

INTRODUCTION

Thyroidectomies form a major bulk of our surgical case turnover (about 600/year), and massive goiters with tracheal compression by itself are not a rare entity. It is commonly suggested in anesthetic practice and training that complete airway occlusion can occur during the induction of anesthesia, during surgical resection or at the time of extubation in large compressive goiters.[1,2,3] This causes apprehension among anesthesiologists with respect to airway management in such cases leading to detailed evaluation and cautious management, thereby precluding rapid case turnover. A recent prospective study on difficult airway in thyroidectomies from a goiter-endemic region (Ethiopia) reported a difficult intubation incidence of 14.3% and concluded that goiter associated with airway deformity is a major risk factor.[4]

Recommended techniques for securing airway in such patients include awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI), awake direct laryngoscopy-aided intubation, and intubation after induction with inhalational agents.[1,2,3,5] Most of the information concerning anesthetic management is limited to isolated case reports and small case series. Review of recently published literature unearthed several controversies, with conflicts of opinion among experts regarding the best primary airway management to the extent that some advocates techniques that are totally condemned by others.[6] This was well evident in a study by Cook et al. where they solicited opinion from the experts in the field of airway management for a patient with severe tracheal compression due to massive retrosternal goiter (mRSG).[6] All the experts were also able to quote evidence to substantiate their preferences, thus further highlighting the lack of consensus.[6]

On auditing our thyroid surgical database, we found that <5% of the patients undergoing thyroidectomy had tracheal compression. This motivated a retrospective analysis, focusing on the airway management of patients with tracheal compression for thyroidectomy. Our objectives were to identify the preferred techniques of airway management in these cases at our institution and also to assess whether airway management was unnecessarily complicated.

METHODS

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Research Committee and Ethical Committee, a retrospective review was undertaken of all patients who underwent thyroid surgery in our institution – a tertiary referral center for 3 years from January 2013 to December 2015.

Patients with radiological and/or clinical features of tracheal compression were included in our study. Radiological tracheal compression was defined as a reduction in the tracheal lumen to <15 mm on computed tomography (CT).[3] Among these, ≤5 mm was taken as critical tracheal compression.[3] Clinical features included pressure symptoms attributable to tracheal compression by the thyroid swelling (breathlessness, cough, and stridor), with or without a positive Pemberton's sign.[1,7]

The case records of these patients were individually examined, and patient characteristics, radiologic, anesthetic, surgical, and pathological data were entered into a structured data sheet [Annexure 1]. Patient characteristics included age, weight, sex, duration of the swelling, presenting symptoms, anesthetic airway assessment including Mallampati class (MP class), indirect laryngoscopy (IL) findings, other difficult airway features, and in particular, whether a difficult airway was anticipated or not. Additional information including comorbidities and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grading were not included in the collected data as we wanted to concentrate directly on the issues relating to the goiter and those factors considered important in the management of the patients’ airway. Radiological findings which were recorded included the presence of tracheal shift, tracheal narrowing, minimum tracheal diameter (MTD) (if mentioned), and extent of retrosternal extension.

Anesthetic data included the technique of induction, ease of bag-mask ventilation, use of muscle relaxant for intubation, experience of the anesthesiologist, difficulties associated with mask ventilation or intubation, size and type of endotracheal tube (ETT) used, and the requirement of airway adjuncts. Difficult mask ventilation (ASA task force) was defined as when it is not possible for an unassisted anesthesiologist to prevent or reverse the signs of inadequate ventilation during positive pressure mask ventilation.[8] Difficult endotracheal intubation was defined as when proper insertion of the tracheal tube with conventional laryngoscopy required more than three attempts or more than 10 min.[8] Problems associated with extubation including the timing of extubation, reintubation, and requirement of tracheostomy were noted.

The recorded surgical data were the need for sternotomy and intraoperative assessment of tracheal wall strength. The occurrence of postthyroidectomy tracheomalacia (PTTM), a condition secondary to the longstanding extrinsic tracheal compression with subsequent loss of tracheal cartilage rigidity, culminating in dynamic airway collapse more than 50% of the diameter was also noted.[3] Postoperative complications, increased length of stay (ILS ≥5 postoperative days), and mortality, if any, were also duly recorded.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative data are represented as frequencies and percentages and quantitative data as mean and standard deviation (SD). Chi-square test was used to compare the qualitative variables and t-test for quantitative variables. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between January 2013 and December 2015, a total of 1861 patients underwent thyroidectomy in our center. Of these, 50 (2.68%) patients had radiological and/or clinical evidence of tracheal compression and were included in our study. Our study population comprised of 46 females and four males, and the mean age was 53.4 years (SD - 11.51). Duration of swelling ranged from 3 months to 30 years (mean 10.81). Etiology of the goiter was benign in 90% (n = 45) and malignancy in the rest (n = 5). There were clinical features attributable to tracheal compression in 80% of the patients (n = 40), with two patients having clinically evident stridor as a presenting feature [Table 1].

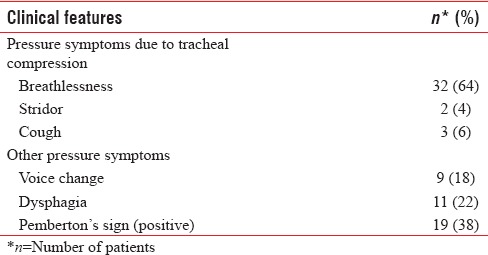

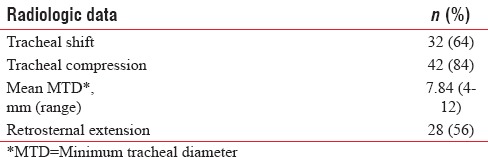

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients with tracheal compression (n=50)

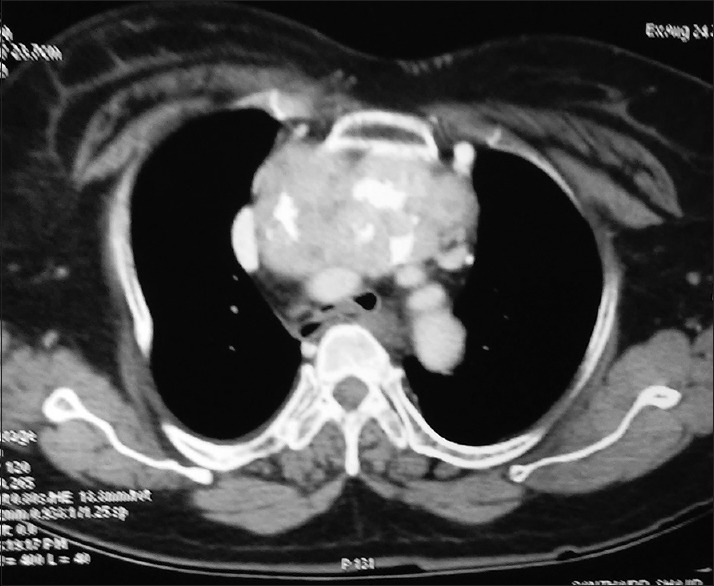

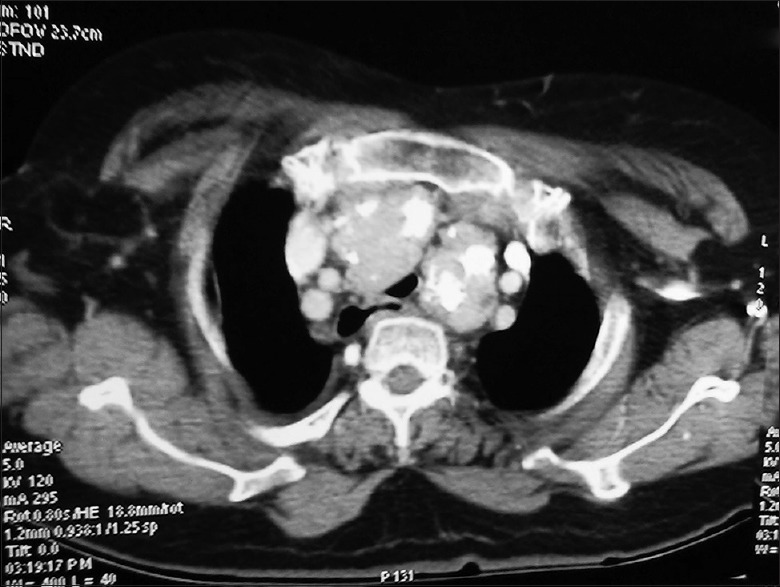

Radiological evidence of tracheal compression was seen in 84% (n = 42) of the study population. Of these, four patients had critical tracheal compression (MTD ≤5 mm) and 22 patients had MTD between 6 and 10 mm [Table 2]. MTD was not quantified in 17 patients though tracheal compression was present radiologically. Both radiological and clinical features of tracheal compression were present in 64% (n = 32) of the patients. Massive retrosternal goiter (mRSG) defined as Grades 2 or 3 (extending to aortic arch and below) by Huins et al. was present in six patients.[9] Among this, one patient had CT findings of gland occupying the whole of anterior mediastinum with compression of trachea and the left main bronchus which necessitated sternotomy [Figures 1 and 2].

Table 2.

Radiologic data from computed tomography, X-ray neck, and ultrasonography neck

Figure 1.

Computerized tomography showing compression of trachea and the left main bronchus by goiter.

Figure 2.

Computerized tomography showing mass occupying entire anterior mediastinum.

Difficult airway was identified and anticipated in all the fifty cases in the preanesthetic evaluation due to the goiter-causing tracheal compression. There were additional features contributing to a potentially difficult airway (short neck, retrognathia, absent, loose or missing teeth, high MP class, dentures, etc.,) other than the goiter in 27 patients. Of these, 21 belonged to MP Class 3 and 4. Preoperative IL was done in 47 patients and vocal cord palsy or restricted cord mobility was detected in eight patients.

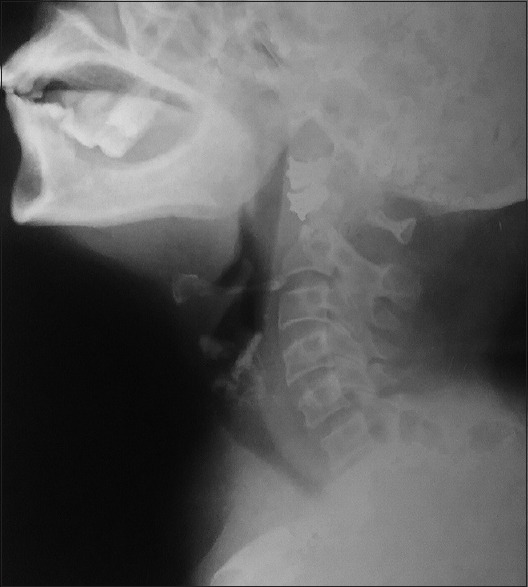

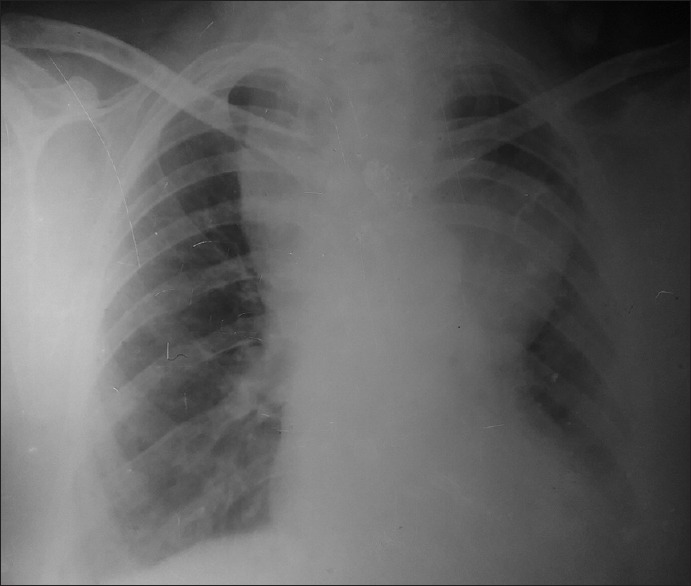

Anesthetic care was provided in all these cases by anesthesiologists of varying degrees of experience ranging from 3 years to 10 years. Majority of anesthesia providers (76%, n = 38) in our survey had more than 5 years of experience. Conventional intravenous (i.v.) induction with bag-mask ventilation followed by intubation under muscle relaxant was performed in 32 patients (64%). Succinylcholine (1–1.5 mg/kg) was the relaxant used in all these cases. Rest of the patients (n = 18, 36%) underwent intubation with the preservation of spontaneous ventilation. They received airway anesthesia prior to intubation. One woman with thyroid swelling of 10 years duration and critical tracheal compression (5 mm MTD) who had breathlessness in the supine position underwent conventional IV induction with propofol and intubation with flexometallic tube (6 mm ID) after succinylcholine in the lateral position [Figures 3 and 4]. Awake intubation was not chosen as the primary technique in any of the cases. The primary intubation technique was successful in all cases with no reported episodes of difficult ventilation or difficult intubation (ASA Task force definition) as per anesthesia records.

Figure 3.

X-ray neck showing critical tracheal compression.

Figure 4.

Chest X-ray showing large retrosternal goiter.

Tracheal tube size varied from 6 to 8.5 mm ID with 12 patients receiving less than ordinary size. Flexometallic tube was used in 18 patients (36%). There were no documented problems with passage of the tracheal tube or subsequent difficulty in ventilation in any of the patients. We had four patients with critical tracheal compression (MTD ≤5 mm), three of whom received normal-sized ETTs. Airway exchange catheter/gum elastic bougie was used in five patients and video laryngoscope in four patients to aid intubation. Of the six patients with mRSG, two required sternotomy. Trachea was reported as “soft” in operative notes of five patients. One of these patients subsequently underwent tracheostomy on the 3rd postoperative day following failed extubation due to probable PTTM. Forty-two patients (84%) were extubated either in the operation theater (74%) or in the immediate postoperative recovery area (10%). One among these had to be re-intubated as she developed stridor due to hematoma, which was subsequently evacuated. Anticipating airway compromise tracheal tube was retained in eight patients, of who six were extubated the next day. Two patients had to undergo tracheostomy following failed extubation, one with suspected PTTM and the other for pulmonary care.

Postoperative hospital stay was uneventful in 45 patients (90%). Five patients developed postoperative complications such as hematoma (n = 1), recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (n = 1), tracheomalacia (n = 1), and pulmonary complications (n = 2). There was ILS in three patients, due to tracheomalacia in one and pulmonary complications in two, who had undergone sternotomy for mRSG. No mortality was reported in the study population.

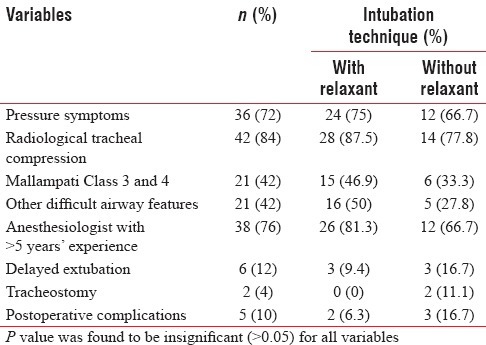

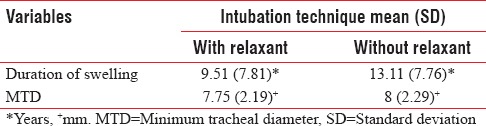

We also compared the group of patients who underwent tracheal intubation with (n = 32) or without (n = 18) muscle relaxant with respect to patient characteristics such as duration of swelling, pressure symptoms, MTD, MP class, and other difficult airway features [Tables 3 and 4]. No significant differences could be detected between the two groups. The two groups were comparable in terms of experience of attending anesthesiologist, extubation characteristics, and postoperative complications [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of qualitative variables against intubation technique

Table 4.

Comparison of quantitative variables against intubation technique

DISCUSSION

Patients with tracheal compression due to goiter pose unique challenges regarding airway management to the practicing anesthesiologist.[1,2,3,5,6,7] Traditional anesthetic concepts warn of difficult airway in thyroid surgeries with airway mishaps possible throughout the perioperative period.[5,6,7] However, review of recent literature revealed that experts differ fundamentally in their opinion of what is ideal practice.[6]

During the past two decades, airway management in cases of difficult airway has undergone a major paradigm shift emphasizing gas exchange over tracheal intubation.[10] Hung and Murphy in their recent paper have put forth a concept of “context-sensitive airway management” emphasizing that it is heavily dependent on the clinical situation and environment.[11] Cook et al. also supports this view and suggests that patient factors, physician expertise, and availability of resources may alter or modify airway management techniques.[6] Dempsey et al. opined that using an unfamiliar technique in a difficult airway unnecessarily overcomplicates matters and potentially adds on to the risks involved.[2]

Majority of our patients were managed with i.v. induction and intubation under muscle relaxant. Succinylcholine with its distinctive short duration provided safe and excellent intubating conditions in these situations. Neither patient characteristics nor radiological findings dictated the choice of muscle relaxation for intubation. Either personal preferences or airway dynamics after induction would have guided the choice of muscle relaxant. In a recently published case series by Dempsey et al. describing the airway management of 19 cases of mRSG, 18 patients underwent conventional i.v. induction and intubation by direct laryngoscopy.[2] Gilfillan et al. resorted to conventional i.v. induction with muscle relaxant following the failure of either AFOI or inhalational techniques for securing the airway.[1] In a prospective study on 91 thyroidectomy cases by Hailekiros et al., though they concluded that goiter accompanied by airway deformity is a risk factor for difficult airway, all patients could be successfully intubated by direct laryngoscopy.

We did not encounter difficult to ventilate or difficult to intubate scenarios (ASA Task force guidelines) in any of the cases. Being a tertiary referral center, we had the backup of expert help, equipment, and surgical assistance including an option for rigid bronchoscopy in case of an adverse situation. Of note, though there was no consensus regarding the primary airway management choices in the study by Cook et al., most of the expert opinion converged on rigid bronchoscopy as backup plan or plan B. Given the fact that 76% (n = 38) of our intubations were done by senior anaesthesiologists with >5 years’ experience, it could contribute to our low incidence of difficulties in airway management.

Cook et al. in their case report describe successful airway management in a case of mRSG causing critical tracheal compression using AFOI as the primary technique.[6] Most anesthesiologists would opt for AFOI as the primary technique in such cases as they would rather prefer to play it safe. Nevertheless, it has many limitations. AFOI in a patient with symptomatic tracheal narrowing can be unpleasant and distressing as it may totally obstruct the airway before the tracheal tube can be secured.[1,7,12] Success depends on patient tolerance, cooperation, and operator skill. Furthermore, it is expensive, time-consuming, and precludes rapid case turnover. As evident from the previous published literature, there is little to support the premise that the presence of a massive goiter alone is likely to cause a difficult direct laryngoscopy.[1,2,3] Gilfillan et al. in their study found that laryngeal inlet was clearly visible on direct laryngoscopy in 87.5% of their cohort of patients diagnosed as having a potentially difficult airway due to retrosternal goiter.[1] We acknowledge that for a less-experienced anesthesiologist in a nonspecialist center, AFOI may be a safer alternative, especially if other causes of a difficult airway coexist.

Varying degrees of tracheal compromise often pose a dilemma in selecting an appropriate-sized ETT. Hailekiros et al. recommended a smaller-sized ETT in the presence of airway deformity associated with goiter.[4] This is in contrast to our findings where 84% of the patients despite the evidence of significant tracheal compression received normal-sized ETTs. This highlights that the selection of tracheal tube size did not necessarily correlate with the degree of tracheal narrowing, but was rather dictated by patient body habitus alone. This may not hold true when tracheal narrowing is due to an infiltrative process as in a malignancy because 90% of our study population had a benign pathology. A benign disease is associated with extrinsic compression rather than a fixed rigid stenosis, which might explain our observation.[2] We did not encounter difficulty with positive pressure ventilation in any patient including 64% who received standard ETTs. We would suggest that the presence of significant tracheal compression does not mandate the use of a flexometallic tube for maintaining airway patency.

In spite of the theoretical possibility of tracheomalacia in longstanding huge thyroids, the majority (84%) of our patients underwent early uncomplicated extubation. Although trachea was reported as soft in five patients, PTTM was suspected in only one patient who developed dynamic airway collapse following extubation, necessitating tracheostomy. Our findings are substantiated in similar studies, reporting a very low incidence of PTTM (<1%), some even suggesting tracheomalacia as a mythical possibility.[1,3,13] A systematic review of retrosternal goiters by Huins et al. described an incidence of tracheomalacia of <1%, but this was reported to be as high as 10% in RSG reaching up to aortic arch.[9]

We were able to identify the requirement of sternotomy as one of the factors leading on to increased postoperative morbidity and ILS, indirectly reflecting on the extent of surgical resection involved for the mRSG as the underlying cause. Sancho et al. reported a high risk of sternotomy, postoperative complications, re-operation, and death in intrathoracic goiter reaching the tracheal carina.[14] Pieracci and Fahey in their extensive database study of 33,600 thyroidectomies comparing outcomes in cervical and substernal thyroidectomies found significantly increased morbidity, postoperative complications, ILS, and an 8-fold increased mortality in substernal thyroidectomies.[15] They also postulated that the increased technical demands imposed on the surgeon for exposure and dissection of a substernal thyroid increase the duration of surgery and anesthesia, which, in turn, escalates the likelihood of postoperative complications and morbidity.

To summarize airway management in goiters with tracheal compression is quite straightforward and can be dealt with in the conventional manner, with minimal airway challenges in the hands of an experienced personnel. We had no instances of difficult ventilation or intubation. Interestingly, we also observed that the degree of tracheal compromise did not influence the selection of size and type of tracheal tube. It is also reassuring to note that contrary to traditional concepts, the risk of tracheomalacia in such cases is quite rare. Substernal thyroidectomy rather than the presence of tracheal compression is associated with adverse outcome and ILS.

The main limitations of our study are its retrospective nature and small study population. Given the rarity of occurrence of thyroid swellings causing tracheal compression in the general population, this is difficult to address. The low incidence may be due to the era of early surgical interventions, lack of hospital picture archiving system, and paucity of protocol-based investigations from surgical units. Being a retrospective study, our database relied on anesthesia case records, which in some instances, may be limited by the extent of documentation and errors in reporting. We acknowledge the inadequacy in the case records including Cormack–Lehane grading and weight of thyroid gland, which were mentioned in only a handful of case records. It is legitimate to assume that these may introduce biases that are difficult to ascertain, but are unlikely to affect the main results and conclusions of the study. However, multicentric prospective trials may be undertaken to further substantiate our results.

CONCLUSION

We may suggest that though thyroid swellings may present with dramatic degrees of tracheal compression, it need not necessarily pose insurmountable airway challenges to the experienced anesthesiologist. Our study illustrates that with experienced professionals in a specialized center, most of these cases can be comfortably managed with conventional i.v. induction and direct laryngoscopy, and hence are mostly uncomplicated. Moreover, employing a familiar technique in a difficult scenario has tangible benefits. In a high-volume center with long waiting list, this allows rapid turnover of cases preventing backlogging. In a developing country with limited resources, this may in due course translate to discernible economic benefits in terms of anesthesia care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Staff, Department of Anesthesiology, Government Medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India, for their support.

Annexure

Annexure 1: Data Sheet

Serial No:

Age: Sex: IP No:

Date of surgery:

History:

Duration of swelling:

-

Pressure symptoms: Yes/No

If yes specify:

Pemberton's sign:

-

Radiological signs: Yes/No

- X-ray tracheal shift/compression

- CT - Minimum tracheal diameter

-

Retrosternal extension: Yes/No

Level:

-

Airway examination

- MP Class:

- Other Relevant:

Indirect laryngoscopic examination:

-

Anesthetic plan

- Primary: Successful: Yes/No

- Plan B:

Anesthesiologist experience in years:

Airway anesthesia given:

Final intubation technique:

Bag and mask ventilation confirmed: Yes/No

Airway adjuncts used:

Cormack–Lehane class:

Size and type of ETT used:

-

Intraoperative findings:

- Retrosternal extension: Yes/No

- Sternotomy:

- Tracheal wall strength:

-

Postoperative period

- Extubation:

-

Postextubation airway incidents

- Re-intubation: Yes/No

-

Tracheostomy: Yes/No

- Reason: Time:

Discharge:

Morbidity: Yes/No

Weight of gland:

Histopathology:

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilfillan N, Ball CM, Myles PS, Serpell J, Johnson WR, Paul E. A cohort and database study of airway management in patients undergoing thyroidectomy for retrosternal goitre. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2014;42:700–8. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1404200604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dempsey GA, Snell JA, Coathup R, Jones TM. Anaesthesia for massive retrosternal thyroidectomy in a tertiary referral centre. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:594–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Findlay JM, Sadler GP, Bridge H, Mihai R. Post-thyroidectomy tracheomalacia: Minimal risk despite significant tracheal compression. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:903–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hailekiros AG, Abiy SW, Getinet HK. Magnitude and predictive factors of difficult airway in patients undergoing thyroid surgery, from a goiter endemic area. J Anesth Clin Res. 2015;6:11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raval CB, Rahman SA. Difficult airway challenges-intubation and extubation matters in a case of large goiter with retrosternal extension. Anesth Essays Res. 2015;9:247–50. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.152421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook TM, Morgan PJ, Hersch PE. Equal and opposite expert opinion. Airway obstruction caused by a retrosternal thyroid mass: Management and prospective international expert opinion. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:828–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong P, Liew GH, Kothandan H. Anaesthesia for goitre surgery: A review. Proc Singapore Healthc. 2015;24:165–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:597–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huins CT, Georgalas C, Mehrzad H, Tolley NS. A new classification system for retrosternal goitre based on a systematic review of its complications and management. Int J Surg. 2008;6:71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung O, Murphy M. Changing practice in airway management: Are we there yet? Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:963–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03018480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung O, Murphy M. Context-sensitive airway management. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:982–3. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d48bbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popat M, Woodall N. Fibreoptic intubation: Uses and omissions. In: Cook T, Woodall N, Frerk C, editors. 4th National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Major Complications of Airway Management in the United Kingdom. London: RCoA; 2011. pp. 114–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tripathi D, Kumari I. Tracheomalacia: A rare complication after thyroidectomy. Indian J Anaesth. 2008;52:328–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sancho JJ, Kraimps JL, Sanchez-Blanco JM, Larrad A, Rodríguez JM, Gil P, et al. Increased mortality and morbidity associated with thyroidectomy for intrathoracic goiters reaching the carina tracheae. Arch Surg. 2006;141:82–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pieracci FM, Fahey TJ 3rd. Substernal thyroidectomy is associated with increased morbidity and mortality as compared with conventional cervical thyroidectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]