Abstract

Context:

Ropivacaine and Levo-Bupivacaine have been safely used for caudal anaesthesia in children, but there are limited studies comparing the efficacy of 0.25% Ropivacaine and 0.25% Levo-Bupivacaine for caudal anaesthesia in infraumbilical surgeries.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to compare the incidence of motor blockade and postoperative analgesia with 0.25% ropivacaine and 0.25% levobupivacaine for the caudal block in children receiving infraumbilical surgery.

Settings and Design:

This was a randomized double-blinded study.

Subjects and Methods:

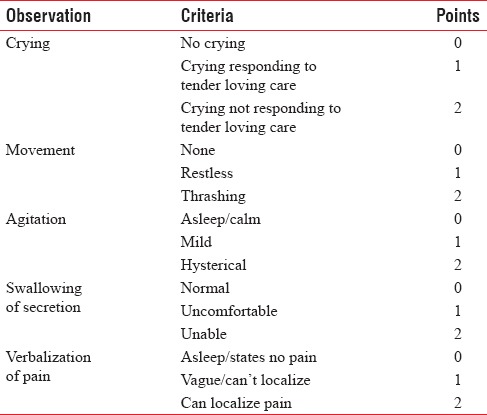

Sixty patients of either sex, between 1 and 10 years posted for elective infraumbilical surgeries, to receive caudal block with either (Group R) ropivacaine 0.25% or (Group L) levobupivacaine 0.25% of volume 1 ml/kg were included in the study. Motor blockade was assessed using motor power scale, and pain was assessed every 1 h for first 6 h, then 2nd hourly for following 18 h using modified Hannallah objective pain scale. If pain score is ≥4, the patients were given paracetamol suppositories 20 mg/kg as rescue analgesia.

Statistical Analysis Used:

All analyses were performed using Chi-square test, Student's independent t-test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results:

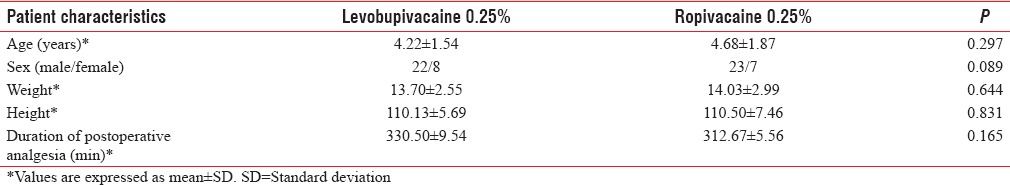

The time for full motor recovery was similar in both groups; in Group R, ropivacaine: 180.50 ± 14.68 min, and in Group L, levobupivacaine: 184.50 ± 18.02 min, with P = 0.163. The duration of postoperative pain relief between the groups was 330.50 ± 9.54 min in Group L (levobupivacaine) and 312.67 ± 5.56 min in Group R (ropivacaine) with P = 0.165 not statistically significant.

Conclusions:

Both ropivacaine 0.25% and levobupivacaine 0.25% have similar recovery from motor blockade and postoperative analgesia.

Keywords: Caudal anesthesia, levobupivacaine, postoperative analgesia and motor blockade, ropivacaine

INTRODUCTION

The most preferred pediatric regional anesthesia techniques are caudal and lumbar epidural blocks and ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and penile nerve blocks.[1,2,3] When compared with adults, lower concentrations of local anesthetics are sufficient in children; rapid onset but the duration is usually less.[4] The search for the ideal adjuvant and a local anesthetic with a wide margin of safety, limited motor blockade, and prolonged period of analgesia continues till date.[5]

Earlier racemic bupivacaine was routinely used for caudal block, to minimize the risk of unwanted motor blockade; anesthesiologist is favoring one of the two new long-acting single enantiomeric local anesthesia drugs, ropivacaine or levobupivacaine.[6]

Ropivacaine is less lipophilic; hence, it is less likely to penetrate large myelinated motor fibers, resulting in a relatively reduced motor blockade and longer postoperative analgesia and has a greater degree of motor sensory differentiation, which could be useful when motor blockade is not desired.[7]

Levobupivacaine provides good epidural anesthesia and analgesia for surgical procedures with relatively longer postoperative analgesia and reduced motor blockade. To date, only few studies have been published comparing levobupivacaine and ropivacaine for the caudal block in children. Therefore, there is a need to study and compare the effectiveness of levobupivacaine and ropivacaine in the caudal block.

The primary aim was to compare the incidence of motor blockade and postoperative analgesia and following use of similar concentrations (0.25%) of ropivacaine and levobupivacaine for the caudal block in children undergoing infraumbilical surgery.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted as a randomized double-blinded study in a teaching hospital in South India. After obtaining the Ethical Committee approval and parental informed written consent, sixty American Society of Anaesthesiologist Physical Status I and II patients of either sex in the age range of 1–10 years posted for elective infraumbilical surgical procedures were selected for this study. Exclusion criteria included children with spinal deformities, any infection at the injection site and the presence of a blood-clotting disorder.

After standard fasting times and premedication (oral midazolam 0.4 mg/kg given 40 min before the procedure), patient was shifted to operation theater. Standard monitors were connected. After recording baseline parameters, intravenous access secured with the 22-gauge cannula, the children were given injection atropine 20 µg/kg intravenous, preoxygenated with 100% O2, and induced with injection ketamine 2 mg/kg intravenous.

Immediately following induction of anesthesia, the patients were randomized using the sealed envelope technique (based on computer-generated random numbers), to receive caudal block with either (Group R) ropivacaine 0.25% or (Group L) levobupivacaine 0.25% of volume 1 ml/kg. The study drug was prepared by a doctor who did not take any further part in the study. Thus, the anesthesiologist performing the block and taking care of the anesthetic was blinded to the drug administered as was the research assistant performing the postoperative assessments.

The patient was positioned in the left lateral and under full aseptic precautions; a sterile 22-gauge needle was introduced in the caudal epidural space. After confirming the position of the needle with whoosh test, the allocated drug was given slowly over 60 s. Then, the patient was turned to supine position; anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (2–3%) in oxygen 6 L/min connected via Jackson-Rees circuit.

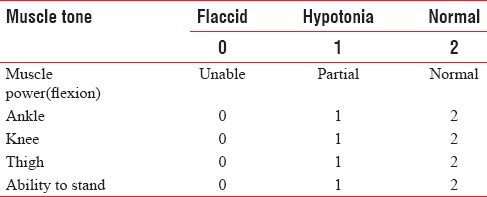

The block was considered successful if there were no hemodynamic changes to the skin incision. After the completion of the surgical procedure, the children were shifted to the postoperative ward for observation for 24 h. Postoperatively, motor blockade was assessed using motor power scale [Table 1], and severity of pain was assessed every 1 h for the first 6 h, then 2nd hourly for following 18 h using modified Hannallah objective pain scale [Table 2]. The patients with a pain score of ≥4 were given paracetamol suppositories 20 mg/kg as rescue analgesia. The time of administration of the first rescue analgesic drug was noted.

Table 1.

Modified Hannallah pain scale

Table 2.

Motor power scale

Sample size

Based on a pilot study, data power calculation (G*power, Germany) was done before the study. The expected mean duration of analgesia for ropivacaine and levobupivacaine was 318 ± 15 min and 325 ± 22 min, respectively. “G*power” calculation indicated that a total sample of 28 patients in each group would be required to have a large effect (d = 0.80) with 90% power using t-test with α = 0.05 and β = 0.2.[8] We, therefore, recruited thirty subjects in each group.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was reported using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM®, USA) software version 19.0. All variables were examined for outliers and nonnormal distributions. The categorical variables were projected as frequency and percentage. The quantity variables were expressed as a mean and standard deviation. Descriptive statistics were used to assess baseline characteristics. The group comparison for the categorical variables was analyzed using Chi-square test and for quantity variables was analyzed using Student's independent t-test. Postoperative analgesia was compared using Kruskal–Wallis test. Motor blockade between the groups was compared by Mann–Whitney U-test. Friedman test was used to see the difference in the motor power scale over different time intervals in a particular group. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

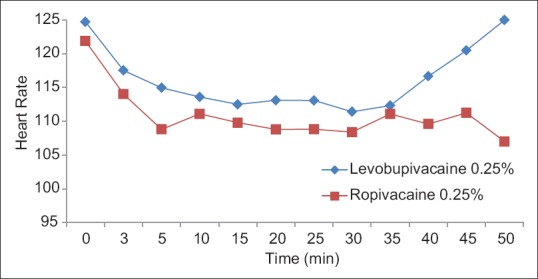

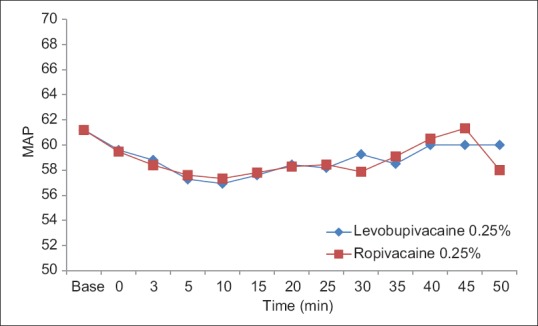

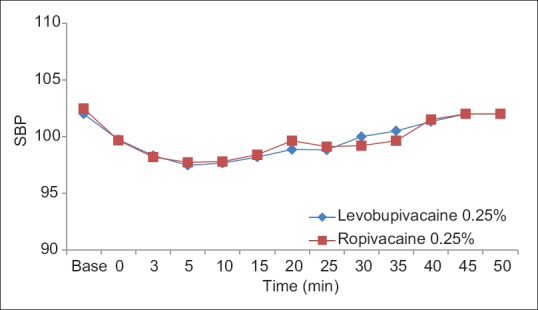

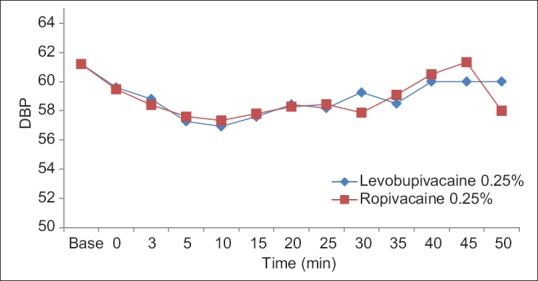

The groups were comparable groups in age, weight, gender, duration of anesthesia, baseline blood pressure, and heart rate [Table 3]. The patients remained hemodynamically stable during the operation in both groups [Figures 1–4].

Table 3.

Demographic data and duration of postoperative analgesia

Figure 1.

Heart rate variation at different time intervals between levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative mean arterial pressure in groups levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

Figure 2.

Intraoperation - systolic blood pressure in groups levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

Figure 3.

Diastolic blood pressure among levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

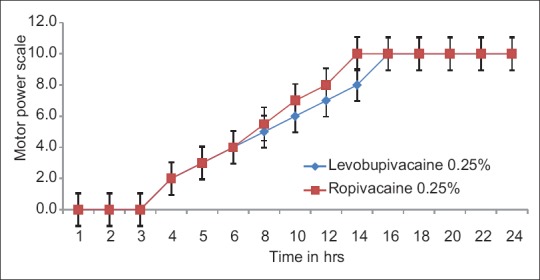

Motor power scale was comparable between the groups with a median. In the beginning of the observational period, the median motor power scale was identical in two groups (P > 0.05). With the progression of time, the median motor power scale observed in both groups were similar but it had statistically significant change (levobupivacaine 0.25% Chi-square = 140, P = 0.000: Ropivacaine 0.25%; Chi-square = 274, P = 0.000). The mean time for full motor recovery was similar in both ropivacaine and levobupivacaine groups; in Group R, ropivacaine: 180.50 ± 14.68 min, and in Group L, levobupivacaine: 184.50 ± 18.02 min, with P = 0.163 (P > 0.05), but this difference is not statistically significant (P > 0.05) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Motor power scale in groups levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

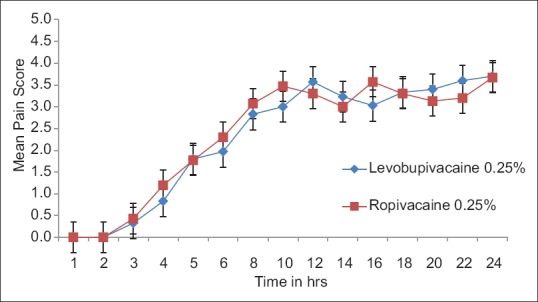

The quality and duration of postoperative pain relief did not differ significantly between the two groups. The lack of analgesia was not found in any patient during surgery, and there is no hemodynamic response to initial incision. Postoperative pain score was fairly similar in two groups in initial 5 h, but it is significantly less in ropivacaine group after 5 h. The average duration of analgesia was 330.50 ± 9.54 and 312.67 ± 5.56 min in Groups L and R, respectively [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Mean pain score in groups levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

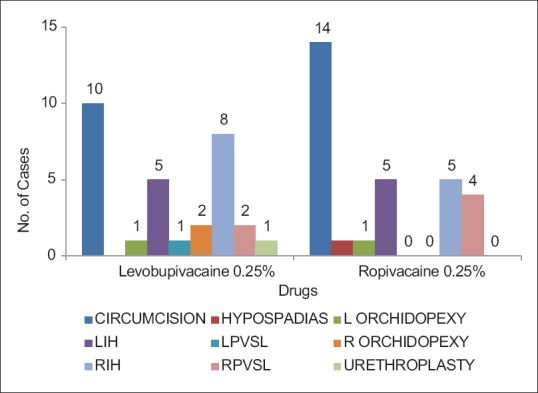

A break up of the different types of surgeries performed in the two groups is given below. Mostly, circumcision surgery was performed in two groups, 33% in levobupivacaine 0.25% group and 47% in ropivacaine 0.25% group. The other important surgical procedures carried out were herniotomy, anatomical mesh repair for umbilical hernia, hypospadias repair, orchidopexy, and urethroplasty [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Type of surgery in group levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25%.

DISCUSSION

In our study, we compared an equal concentration (0.25%) of ropivacaine and levobupivacaine for a single injection caudal anesthesia in children receiving infraumbilical surgeries; the incidence and degree of the early postoperative motor blockade and postoperative analgesia were comparable between the two local anesthetic agents. Thus, clinically, these two new local anesthetics appear almost similar when used at equal concentrations for the caudal blockade in children undergoing minor infraumbilical surgery.

Locatelli et al.[9] suggested that studies with small sample size may reach the erroneous conclusion, and to establish a statistically significant difference, if such exists with a 3% variations, we should study more than 1200 patients/group. So far, very few studies have been published comparing ropivacaine and levobupivacaine for regional anesthesia in children.[10,11,12]

Ivani et al. compared commercially available concentrations of ropivacaine (0.2%), levobupivacaine (0.25%), and racemic bupivacaine (0.25%). They found that the quality of postoperative analgesia was similar, but the use of ropivacaine was associated with significant reduction in early postoperative motor blockade compared with racemic bupivacaine. Although not significant, a similar tendency for less motor blockade was observed when ropivacaine was compared with levobupivacaine.[11] These results were similar to the results of our study. That observation could be due to a lower concentration of ropivacaine used compared with the two different bupivacaine preparations. Astuto et al. did not observe motor blockade following surgery using ropivacaine 0.25% or levobupivacaine 0.25%.[10] However, in a study by Locatelli et al., they found more than half of their patients receiving levobupivacaine 0.25% and ropivacaine 0.25% presented with some amount of motor block at wake-up.[9] Ivani et al.[13] reported that 2 mg/kg of 0.2% ropivacaine is enough to obtain sensory block for lower abdominal or genital surgery in children. Since pharmacokinetic studies of ropivacaine show that 1 ml/kg 0.25% ropivacaine by the caudal block brings about a maximal plasma concentration of 0.72 ± 0.24 mg, which is much lower than the maximal tolerated plasma concentration of ropivacaine in adult volunteers (2.2 ± 0.8 mg/L).[14,15] Habre et al.[14] reported that the maximum plasma concentration of ropivacaine was achieved at 2 h, following caudal block which is much later than for bupivacaine (29 ± 3.1 min) in children. Another reason of using 0.25% ropivacaine is to avoid motor blockade in the postoperative period, which may occur with higher concentration. However, Da Conceicao and Coelho[16] reported a significantly less duration of motor block with 0.375% ropivacaine as compared to bupivacaine. Ray et al.[17] reported that all patients had some amount of motor weakness in both groups, immediately after surgery. Later, after 2 h, nearly normal motor power was recorded in ropivacaine group. Khalil et al.[18] also reported significant motor block initially, which nearly recovered to normal power with 3 h in ropivacaine group. Motor recovery was significantly delayed in bupivacaine group in their series. Quality and duration of analgesia did not vary significantly between the two groups. The average duration of analgesia was 398 ± 23 min in bupivacaine group and 405 ± 18 min in ropivacaine group in this series.

In our study, the duration of postoperative analgesia was nearly similar with 0.25% levobupivacaine and 0.25% ropivacaine. Locatelli et al.[9] and Astuto et al.[10] reported similar findings in their studies. Ivani et al.[13] observed a prolonged duration of analgesia with ropivacaine 0.2% compared to 0.25% bupivacaine.

We recommend further prospective multicenter studies with larger sample size to find out the difference in postoperative analgesia and motor blockade following the use of similar concentrations (0.25%) of ropivacaine and levobupivacaine for caudal anesthesia in children undergoing infraumbilical surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Caudal ropivacaine 0.25% and levobupivacaine 0.25% have similar recovery from motor blockade and postoperative analgesia and can be safely used for pediatric anesthesia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Markakis DA. Regional anesthesia in pediatrics. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2000;18:355–81. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(05)70168-1. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansermino M, Basu R, Vandebeek C, Montgomery C. Nonopioid additives to local anaesthetics for caudal blockade in children: A systematic review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:561–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobias JD. Caudal epidural block: A review of test dosing and recognition of systemic injection in children. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1156–61. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jöhr M. Regional anaesthesia in neonates, infants and children: An educational review. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:289–97. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lönnqvist PA. Adjuncts to caudal block in children – Quo vadis? Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:431–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivani G, De Negri P, Lonnqvist PA, L’Erario M, Mossetti V, Difilippo A, et al. Caudal anesthesia for minor pediatric surgery: A prospective randomized comparison of ropivacaine 0.2% vs. levobupivacaine 0.2% Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:491–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajwa SJ, Kaur J. Clinical profile of levobupivacaine in regional anesthesia: A systematic review. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:530–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locatelli B, Ingelmo P, Sonzogni V, Zanella A, Gatti V, Spotti A, et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase III, controlled trial comparing levobupivacaine 0.25%, ropivacaine 0.25% and bupivacaine 0.25% by the caudal route in children. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:366–71. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astuto M, Disma N, Arena C. Levobupivacaine 0.25% compared with ropivacaine 0.25% by the caudal route in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20:826–30. doi: 10.1017/s0265021503001339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivani G, DeNegri P, Conio A, Grossetti R, Vitale P, Vercellino C, et al. Comparison of racemic bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and levo-bupivacaine for pediatric caudal anesthesia: Effects on postoperative analgesia and motor block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:157–61. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2002.30706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Negri P, Ivani G, Tirri T, Modano P, Reato C, Eksborg S, et al. A comparison of epidural bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine on postoperative analgesia and motor blockade. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:45–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000120162.42025.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivani G, Mereto N, Lampugnani E, Negri PD, Torre M, Mattioli G, et al. Ropivacaine in paediatric surgery: Preliminary results. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:127–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1998.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habre W, Bergesio R, Johnson C, Hackett P, Joyce D, Sims C. Plasma ropivacaine concentrations following caudal analgesia in children. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1245. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2000.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudsen K, Beckman Suurküla M, Blomberg S, Sjövall J, Edvardsson N. Central nervous and cardiovascular effects of i.v. infusions of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and placebo in volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:507–14. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Da Conceicao MJ, Coelho L. Caudal anaesthesia with 0.375% ropivacaine or 0.375% bupivacaine in paediatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:507–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ray M, Mondal SK, Biswas A. Caudal analgesia in paediatric patients: Comparison between bupivacaine and ropivacaine. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:275–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalil S, Campos C, Farag AM, Vije H, Ritchey M, Chuang A. Caudal block in children: Ropivacaine compared with bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1279–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]