Abstract

Background and Aim:

Meperidine and paracetamol are frequently used in postoperative pain control. We evaluated the effect of paracetamol versus meperidine on postoperative pain control of elective cesarean section in patients under general anesthesia.

Materials and Methods:

In this randomized double-blind study, seventy mothers’ candidate for cesarean section under general anesthesia were randomized in paracetamol group (n = 35), received 1 g paracetamol in 100 ml normal saline, and meperidine group (n = 35), received 25 mg meperidine in 100 ml normal saline and then compared regarding the pain and vomiting severity based on visual analog scale (VAS).

Results:

Two groups did not show significant difference regarding pain score based on VAS during 30 min after surgery in the recovery room, however, the pain score after 30 min in paracetamol group was significantly more than meperidine group. The difference between two groups regarding pain score in surgery ward at 0, 2, 4, 6 h, were not significant, however, pain score after 6 h in meperidine group was significantly lower than paracetamol group. The score of vomiting based on VAS in the recovery room in meperidine group was marginally more than paracetamol group (P > 0.05). The score of vomiting, based on VAS in meperidine group was significantly more than paracetamol group during the 24 h in the surgery ward. The analgesic consumption in meperidine group during 24 h after surgery was significantly lower than paracetamol group.

Conclusion:

We indicated that the meperidine decreased postoperative pain score and analgesic consumption more than paracetamol, but increased the vomiting score.

Keywords: Cesarean section, general anesthesia, meperidine, paracetamol, postoperative pain

INTRODUCTION

Cesarean delivery is the most frequent surgery worldwide, and its rate is increasing.[1] Therefore, recently, the authors have focused on improvement of postoperative pain control to improve the patients’ satisfaction and ability to function after surgery.[2] Postcesarean section analgesia has improved in recent years; however, some authors indicated that more than 75% of mothers have reported moderate to severe pain after the operation.[3,4,5] The most common analgesics in postcesarean section pain relief are opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[6,7] Use of opioids is limited because opioids are related to several side effects in mothers and neonates such as pruritis, nausea/vomiting, sedation, and respiratory depression.[8,9] Meperidine, morphine, and fentanyl are the most common opioids which primarily affect the µ-receptors, which induce sedation, analgesia, and some side effects such as vomiting and pruritis. Among these, meperidine is the weakest agonist and less potent opioid.[10] Paracetamol is a well-known analgesic drug used for pain control in mothers.[11,12] It affects both central and peripheral pathways through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and the cyclooxygenase 2 pathway inhibition[4] Meperidine is the first synthetic opioid presented in 1932.[13] Some studies indicated that in patients with obstetric analgesia, meperidine is a more effective agent than tramadol without significant side effects.[14] Pain control is the most important key to improving mothers’ satisfaction and baby care after cesarean section; therefore, different investigators have used several agents to decrease pain, however, many patients, continue to experience inadequate pain relief. On the other hand, although meperidine and paracetamol are commonly using in postoperative pain control, but studies comparing these two agents are rare, therefore, to address these concerns, we conducted this study to evaluate the effect of paracetamol versus meperidine on postoperative pain of elective cesarean section in patients under general anesthesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this randomized double-blinded prospective study, seventy primigravid women candidate for elective cesarean section referring to Shariati Hospital in Bandar Abbas were recruited during 2013–2014. The criteria for enrollment were primigravida, American Society of Anaesthesiologists I, II and lack of preeclampsia, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, and other serious diseases. Exclusion criteria were sensitivity to drugs using in this trial, complicated pregnancy, death, and absence of written consent. The study procedure was explained to all patients, and a written informed consent was obtained. The study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. The standard operating room monitoring, including noninvasive blood pressure, electrocardiogram, and pulse oximetry were performed for all patients. Before induction of anesthesia ringer lactate, 500 ml was infused to all patients, and the general anesthesia was induced by sodium thiopental 4 mg/kg and succinylcholine 1.5 mg/kg intravenously (IV). Then the patients were intubated, and the cesarean section was initiated after anesthesiologist permission. The patients were randomized into two groups based on random allocation, after delivery, and umbilical cord clamping, the patients in the 1st group received 1 g paracetamol (Apotel®, Exir Pharmaceutical Co., Fac: Boroujerd City, Tehran, Iran) in 100 ml normal saline solution (paracetamol group, n = 35), and the patients in the 2nd group received 25 mg meperidine (Pethidine 50®, Caspian Tamin Pharmaceutical Co., Rasht, Iran) in 100 ml normal saline solution (meperidine group, n = 35). The solutions of administration were infused in 20 min in both groups, and both groups were monitored for 24 h after operation (0, 2, 4, 6, 12, 18, 24 h). Both participants and study staff (site investigators and trial coordinating center staff) were blinded to treatment allocation. During the 24 h of operation, the level of pain based on visual analog scale (VAS), blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, heart rate (HR), and analgesic consumption were checked immediately after section and at 2, 4, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h after the operation in the ward. If the score of pain was more than 3 then meperidine 25 mg IV was administered until the VAS decreased to under 3. If the vomiting was severe ondansetron 4 mg was injected. The first request for the analgesic agent was recorded; the patients with severe bleeding and hysterectomy were excluded from the study.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data were presented as (n%), and continuous data as mean ± standard deviation. We used the Student's t-test to compare continuous variables in two groups. The value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

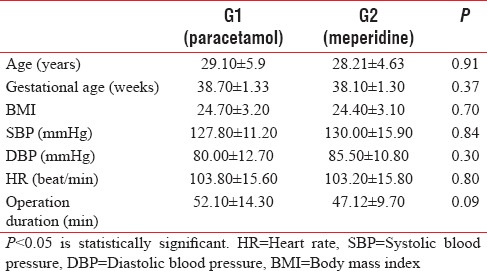

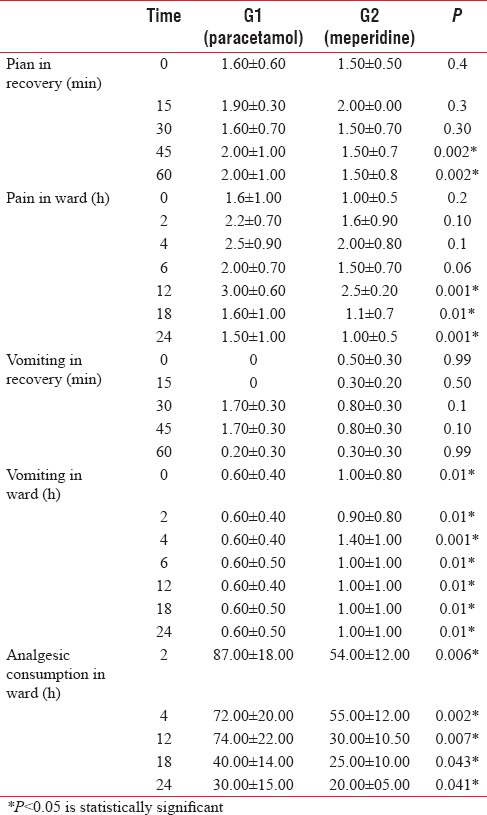

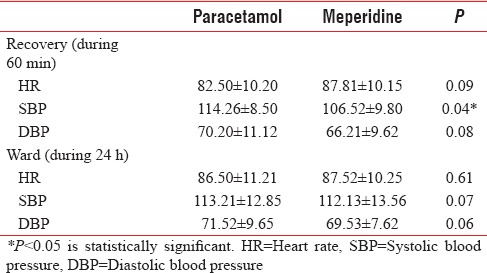

The comparison of patients regarding characteristics at baselines such as age, gestational age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), HR and duration of surgery did not show a significant difference [Table 1]. The pain scores measured at 45 and 60 min after surgery in paracetamol group were significantly more than meperidine group [Table 2]. The difference between the two groups regarding pain scores in the surgery ward at 0, 2, 4, 6 h after surgery, was not significant, however, pain scores after 6 h in meperidine group was significantly lower than paracetamol group [Table 2]. Regarding vomiting in the recovery room, there was no significant difference between the two groups based on the VAS scores but, during 24 h in the surgery ward, the meperidine group had significantly higher vomiting scores than the paracetamol group [Table 2]. The analgesic consumption in the meperidine group during 24 h after surgery was significantly lower than the paracetamol group [Table 2]. The difference between two groups regarding SBP in the recovery room was significant; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding HR and DBP in the recovery room and also HR, SBP, and DBP in the ward [Table 3].

Table 1.

Demographic variables and hemodynamic values in two groups

Table 2.

Comparison of two groups regarding pain and vomiting score based on visual analog scale in recovery room and in ward and analgesic consumption in ward

Table 3.

Comparison of hemodynamic changes in two groups

DISCUSSION

Like other surgeries, postcesarean section pain decreases the ability and function of mothers and affects the maternal care of the neonates. Severe postoperative pain increases the postoperative incidence of nausea and vomiting moreover increases the hospital stay, atelectasis, hypoxemia, pulmonary secretions, etc.[15] To decrease the severity of postcesarean pain and improving patients satisfaction several agents such as acetaminophen, opioids, and NSAIDs are frequently used and some advantages and disadvantages related to these drugs are reported.[6,10] Analgesics that are used perioperatively for cesarean section, in addition to being effective, must not either depress the neonate's respiratory function or decrease the Apgar score. In this study, we compared meperidine with paracetamol in seventy women who underwent cesarean section operation with general anesthesia and showed that the pain VAS score after 6 h in meperidine group was significantly lower than paracetamol group; moreover, the analgesic consumption in meperidine group during 24 h after surgery was significantly lower than paracetamol group. Moreover, the VAS score of vomiting during 24 h of surgery ward stay in the meperidine group was more than paracetamol group. In contrast to our findings in a study by Ayatollahi et al. in 2014 indicated that IV paracetamol is an effective agent to provide better postoperative pain management without considerable neonatal complications in women undergoing cesarean section and general anesthesia.[16] In addition, another study by Varrassi et al. detected that proparacetamol is effective in the management of postoperative gynecologic surgery pain when combined with an opioid agent.[17] In line with these results Moon et al. indicated that preoperative paracetamol in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy decreased the consumption of opioid and related side effects.[18] In contrast to our trial, some other studies revealed the effect of paracetamol in postoperative pain control is comparable with opioids, as in a study by Hassan in 2014 indicated that the administration of paracetamol and meperidine in patients undergoing cesarean section with general anesthesia is an effective agent for hemodynamic stability and reduction of postoperative pain scores.[19] Moreover, Landwehr et al. indicated that paracetamol and metamizole had similar analgesic effects.[20] Another study by Van Aken et al. did not show a significant difference between morphine and paracetamol in post dental surgery pain.[21] Furthermore, in another study by Gin et al. indicated no significant difference between intramuscular ketorolac and meperidine in post cesarean section pain control.[22] The severity of vomiting in our trial in paracetamol group was lower than meperidine group. In agreement with our findings related to drug side effects a study by Shen et al. indicated that paracetamol is an effective and safe agent without clinically significant drug interactions and without the adverse effects related to other analgesics.[23]

Our study was one of few studies comparing the effects of paracetamol and meperidine on pain after elective cesarean section. Probably the different sites of action of paracetamol and meperidine in the nervous system are the cause of different results we reported here.[24]

There are a number of limitations to this study such as small sample size and short duration of study that warrant mention. These limitations restrict the ability to generalize the result of our survey. Further investigations are recommended with longer follow-up and larger series to validate the findings reported here. Further follow-up of current cohorts will answer the question regarding whether these drugs are true pain modifiers.

CONCLUSION

the results of this randomized trial indicated that meperidine is more effective than paracetamol to reduce postoperative pain and analgesic consumption, however, meperidine causes more vomiting.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all patients for participating in our study, the nursing staff, the administrative, and secretarial staff of the anesthesiology and intensive care and pain management research center and Shariati clinic and hospital for their contribution to the maintenance of our patient record without which this project would have been impossible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mayor S. 23% of babies in England are delivered by caesarean section. BMJ. 2005;330:806. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7495.806-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavand’homme P. Chronic pain after vaginal and cesarean delivery: A reality questioning our daily practice of obstetric anesthesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warfield CA, Kahn CH. Acute pain management. Programs in U.S. hospitals and experiences and attitudes among U.S. adults. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:1090–4. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199511000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: Results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:534–40. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang N, Cunningham F, Laurito CE, Chen C. Can we do better with postoperative pain management? Am J Surg. 2001;182:440–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swart M, Sewell J, Thomas D. Intrathecal morphine for caesarean section: An assessment of pain relief, satisfaction and side-effects. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:373–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.az0083c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dualé C, Frey C, Bolandard F, Barrière A, Schoeffler P. Epidural versus intrathecal morphine for postoperative analgesia after caesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:690–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abouleish E, Rawal N, Rashad MN. The addition of 0.2 mg subarachnoid morphine to hyperbaric bupivacaine for cesarean delivery: A prospective study of 856 cases. Reg Anesth. 1991;16:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilder-Smith CH, Hill L, Dyer RA, Torr G, Coetzee E. Postoperative sensitization and pain after cesarean delivery and the effects of single im doses of tramadol and diclofenac alone and in combination. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:526–33. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068823.89628.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N, Aster J. Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, USA: W.B Saunders Co; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bannwarth B, Pehourcq F. Pharmacological rationale for the clinical use of paracetamol: Pharmakinetic and pharmadynamic issues. Drugs. 2003;63:2–5. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day RO, Graham GG, Whelton A. The position of paracetamol in the world of analgesics. Am J Ther. 2000;7:51–4. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200007020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konefal H, Jaskot B, Czeszynska MB. Pethidine for labor analgesia; monitoring of newborn heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation during the first 24 hours after the delivery. Ginekol Pol. 2012;83:357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keskin HL, Keskin EA, Avsar AF, Tabuk M, Caglar GS. Pethidine versus tramadol for pain relief during labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:11–6. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke RS. Wylie and Churchill-Davidson's A Practice of Anaesthesia. 6th ed. London: Hodder Arnold Publications; 1995. Intravenous anesthetic agents: Induction and maintenance; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayatollahi V, Faghihi S, Behdad S, Heiranizadeh N, Baghianimoghadam B. Effect of preoperative administration of intravenous paracetamol during cesarean surgery on hemodynamic variables relative to intubation, postoperative pain and neonatal Apgar. Acta Clin Croat. 2014;53:272–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varrassi G, Marinangeli F, Agrò F, Aloe L, De Cillis P, De Nicola A, et al. A double-blinded evaluation of propacetamol versus ketorolac in combination with patient-controlled analgesia morphine: Analgesic efficacy and tolerability after gynecologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:611–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199903000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon YE, Lee YK, Lee J, Moon DE. The effects of preoperative intravenous acetaminophen in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1455–60. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassan HI. Perioperative analgesic effects of intravenous paracetamol: Preemptive versus preventive analgesia in elective cesarean section. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8:339–44. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.143135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landwehr S, Kiencke P, Giesecke T, Eggert D, Thumann G, Kampe S. A comparison between IV paracetamol and IV metamizol for postoperative analgesia after retinal surgery. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1569–75. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Aken H, Thys L, Veekman L, Buerkle H. Assessing analgesia in single and repeated administrations of propacetamol for postoperative pain: Comparison with morphine after dental surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:159–65. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000093312.72011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gin T, Kan AF, Lam KK, O’Meara ME. Analgesia after caesarean section with intramuscular ketorolac or pethidine. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1993;21:420–3. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9302100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen X, Wang F, Xu S, Ma L, Liu Y, Feng S, et al. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy of preemptive and preventive tramadol after lumpectomy. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60:415–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RD, Cohen NH, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Young WL. Miller's Anesthesia. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]