Abstract

Background:

Various sedative and analgesic techniques have been used for pain relief during oocyte retrieval which is the most painful part of in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures.

Aim:

This study aimed at comparing dexmedetomidine and midazolam for conscious sedation in women undergoing transvaginal oocyte retrieval during an IVF program.

Settings and Design:

Prospective randomized double-blinded comparative study.

Patients and Methods:

Fifty-two patients undergoing oocyte retrieval in their first IVF cycle were randomly allocated into two equal groups. The intervention started with giving fentanyl1 mcg/kg intravenous (IV) followed by paracervical block in both groups. Then, subjects in group (D) received dexmedetomidine at a loading dose of 1 μg/kg IV over 10 min followed by 0.5 μg/kg/h infusion until Ramsay Sedation Scale (RSS) reached 3–4. Patients in group (M) received a loading dose of midazolam 0.06 mg/kg IV over 10 min followed by 0.5 mg incremental doses until RSS reached 3–4.

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS program version 19 and EP 16 program.

Results:

Visual analog scale scores significantly decreased in group D than group M at 5 and 10 min during the procedure (P = 0.03 and 0.01, respectively), and at 20 min during postanesthesia care unit (PACU) time (P = 0.04). Intraoperative rescue sedation by propofol and postoperative rescue analgesia by acetaminophen showed a highly significant decrease (P < 0.01) in group D compared with group M. Furthermore, the time of PACU stay was significantly less (P < 0.01) in group D (49.03 ± 12.8 min) compared to group M (62.5 ± 18.34 min). Although significant bradycardia was noted in group D (23% of patients) during the procedure (P = 0.02), no cases were reported in group M. Patient satisfaction was significantly higher in group D (P < 0.1).

Conclusion:

Dexmedetomidine is an effective analgesic alternative to midazolam during oocyte retrieval for IVF. It offered not only a shorter PACU stay without significant side effects, but also better overall patient satisfaction scores.

Keywords: Conscious sedation, dexmedetomidine, in vitro fertilization, midazolam, oocyte retrieval, pain relief

INTRODUCTION

In vitro fertilization (IVF) is a well-established treatment for some cases of infertility which is increasingly being practiced worldwide.[1] IVF is a four-stage procedure involving:[1] ovarian stimulation protocols to induce the development of multiple follicles,[2] oocyte retrieval,[3] fertilization, and finally[4] embryo transfer.[2] Ultrasound-guided transvaginal follicle aspiration has become the gold standard technique for oocyte retrieval, and it may be the most painful stage among IVF procedures.[3,4] The pain experienced during oocyte aspiration is caused by the passage of the needle through the vaginal wall and by mechanical stimulation of the ovary.[5]

The optimal anesthetic technique during oocyte retrieval should provide safe, effective analgesia, few side effects, a short recovery time, and be nontoxic to the oocytes which are being retrieved.[4,6] Studies suggest higher pregnancy and delivery rates if conscious sedation or epidural anesthetic were used instead of general anesthesia.[7]

Although the best type of analgesia for oocyte retrieval has not yet been established, the use of “conscious sedation” as a means of pain control and anxiolysis, with or without local anesthesia/paracervical block, reduces some of the risks associated with deep sedation, or general anesthesia during transvaginal oocyte retrieval.[7,8] Conscious sedation alone, on the other hand, may be associated with higher postoperative side effects such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and drowsiness.[9,10]

The most commonly used medications for monitored anesthesia care (MAC) are midazolam, propofol, and fentanyl. Unfortunately, all these drugs cause respiratory depression.[11] Midazolam is the shortest-acting benzodiazepine available. Despite its rapid onset, it can cause prolonged sedation following repeated administration due to a relatively long half-life.[12] Combining midazolam with opioids increases the risk of hypoxemia and apnea. Furthermore, adding propofol may cause cardio-respiratory depression.[13]

Dexmedetomidine is a centrally acting α-2 receptor agonist with both sedative and analgesic properties, yet devoid of respiratory depressant effects.[14] Therefore, it is an effective baseline sedative providing better patient satisfaction, less opioid requirements, and less respiratory depression than midazolam and fentanyl.[15] The use of dexmedetomidine, however, may be limited by increased incidence of hypotension and bradycardia and limited ability to achieve deep sedation, when indicated.[16]

The aim of the study was to compare the use of dexmedetomidine and midazolam for conscious sedation in women undergoing transvaginal oocyte retrieval in terms of pain relief and patient satisfaction during an IVF program.

Patients and Methods

After approval of the medical ethical committee, 52 patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status class I and II were enrolled in this prospective randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. The nonpremedicated patients included in this study were between 25 and 38 years of age and were planned for ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval in an IVF program. This study was conducted at Dr. Soliman Fakeeh Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia between September 2014 and April 2015. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participating in the study.

We included patients having their first IVF cycle and showing bilateral ovarian follicular response; since pain scores during oocyte collection may be influenced by repeated IVF experiences. Exclusion criteria were psychological abnormalities, cardio-respiratory, renal, or liver diseases, patients requesting a general anesthesia, and less than three dominant follicles present in either ovaries. Chronic alcohol/drug abusers and those allergic to any of the medications used in the study were also excluded.

Women who fulfilled the eligibility criteria began down-regulation treatment on days 21–22 of the pretrial cycle. On patient's arrival at the IVF unit, preoperative check-up was carried out, and the procedure was explained. Each patient was instructed on the use of a standard 100 mm linear visual analog scale (VAS) with “0” as no pain and “100” as the worst pain imaginable.[17]

Baseline measurements of heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), respiratory rate (RR), and room air oxygen saturation (SpO2) were obtained using an electrocardiogram, a “Dinamap” automated blood pressure monitor and a pulse oximeter, respectively. Those parameters were recorded after the loading dose of the drug under study was given and then every 5 min, till completion of the procedure. Venous access was secured by 20 G cannula, Ringer's Lactate drip (10 ml/kg/h) was started, and oxygen facemask (6 l/min) was applied.

Patients were randomized into group (D) and group (M) with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The allocated intervention was written on a slip of paper, placed in serially numbered, opaque envelopes, and sealed. The envelopes were serially opened, and the allocated intervention was implemented. Patients were equally distributed in both groups. Both investigators and patients were blind to which method was being used. Patients were followed from the point of randomization until complete recovery.

Initially, all patients in both groups received intravenous (IV) fentanyl (1 mcg/kg) followed by a paracervical block 3,3’,4,4’-tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB) in the form of four injections given at 2, 4, 8, and 10 o’clock positions, comprising a total of 100 mg of lidocaine 1% (10 ml of Xylocaine™ 10 mg/ml, AstraZeneca Sverige AB). We used a needle 0.9 mm in diameter and 120 mm in length (Mediplast AB, Malmö, Sweden).[4]

Patients in group (D) received IV dexmedetomidine in a loading dose of 1 mcg/kg over 10 min followed by 0.5 mcg/kg/h infusion until they scored 3–4 on the Ramsay Sedation Scale (RSS) (3: responds to commands only; 4: brisk response to light glabellar tap or a verbal stimulus).[18] Group (M) received IV midazolam in a loading dose of 0.06 mg/kg over 10 min followed by 0.5 mg incremental doses until RSS reached 3–4. VAS scores were recorded at 5-min intervals intraoperatively and 20-min intervals in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

During the procedure, if the patient or surgeon were uncomfortable, rescue IV sedation was given in the form of propofol top-up increments of 0.25 mg/kg until the patient reached RSS 3–4. The total requirements of the rescue sedative drug were recorded.

Intraoperatively, complications were observed, recorded, and treated accordingly as discussed later. Oxygen desaturation was considered when SpO2 dropped below 93% for more than 10 s. Bradycardia was defined as a HR under 50 beats/min or a 20% decrease from the baseline, whereas a HR more than 20% of the baseline was labeled as tachycardia. A drop in MAP by 20% or more of the baseline was regarded as hypotension while an MAP value higher than the baseline by 20% was regarded as hypertension. Other possible complications such as respiratory depression, allergic reactions, coughing, gagging, dizziness, restlessness, headache, nausea, and vomiting were recorded and managed accordingly. For example, IV ondansetron 4 mg was given as a rescue antiemetic.

In the recovery room, all vital signs were recorded every 5 min and pain score (VAS) was measured every 20 min. Patients whose VAS was more than 3 received an IV infusion of acetaminophen 1 g (Perfalgan™, Bristol–Myer's Squibb). The total amount of acetaminophen given as a rescue analgesic was recorded. Any adverse effects such as restlessness, dizziness, headache, nausea, and vomiting were recorded and managed accordingly.

Criteria for discharge from the PACU were full consciousness, hemodynamic stability, and the absence of significant pain, nausea, and/or vomiting. The procedure time (measured from initiation of PCB until the end of oocyte retrieval) and the time of PACU stay (measured from the end of oocyte retrieval until patient's transfer to the ward) were recorded. Before discharge to the ward, patient's satisfaction was assessed using the 7-point Likert scale:[19] 1 = extremely dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = somewhat dissatisfied, 4 = undecided, 5 = somewhat satisfied, 6 = satisfied, and 7 = extremely satisfied.

The number of oocytes obtained, embryos transferred per patient, and percentage of pregnancy per embryo transferred were all registered.

The sample size was calculated according to a confidence interval of 95% and power of the test of 80%; considering the primary outcome of this study as the length of PACU stay. Based on a previous investigation, 20 patients per group was the minimum sample size required to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the duration of PACU stay. In our study, we included 52 patients, 26 in each group.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS program version 19 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and EP16 program. Student's t-test, Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U-test, and Fisher's exact test were used for statistical analysis, as appropriate. Data are presented as a mean ± standard deviation, median, numbers, and frequencies, as appropriate. Statistical significance was determined at a P < 0.05, whereas P < 0.01 was considered as highly significant.

RESULTS

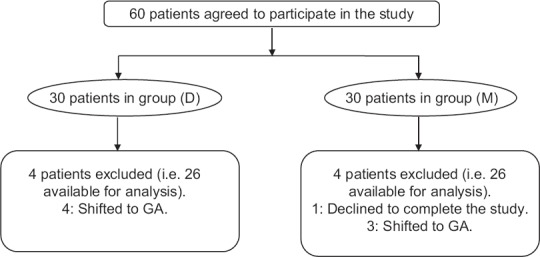

From 60 consecutive patients scheduled for oocyte retrieval during the study period, eight were excluded; four in group D (shifted to general anesthesia due to patient's irritability) and four in group M (one patient declined to complete the study due to personal reasons; the remaining three patients were shifted to general anesthesia due to patient's irritability). Hence, 52 patients were enrolled in the study (26 patients randomly allocated in each group) to be considered for analysis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

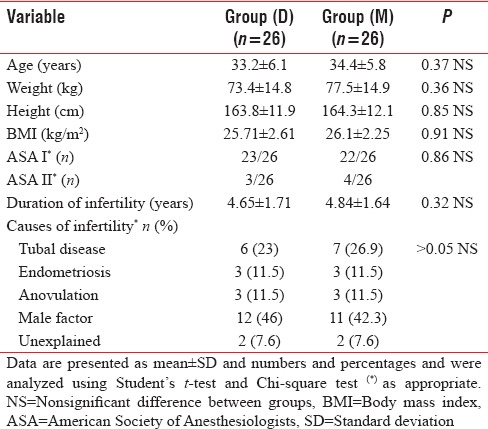

Demographic data (age, weight, height, body mass index, and ASA classification) were comparable, and no statistically significant differences were observed between groups. In addition, there were no significant differences regarding the duration and cause of infertility [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients, duration and causes of infertility

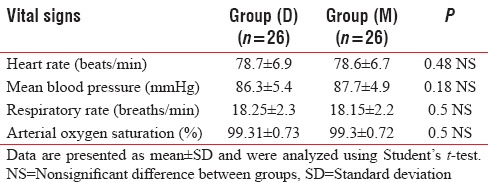

The mean values of baseline HR (beats/min), mean blood pressure (mmHg), RR (breaths/min) and arterial SpO2 (%) were comparable between groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean values of baseline vital signs

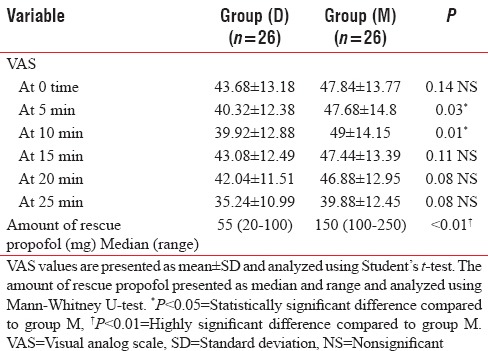

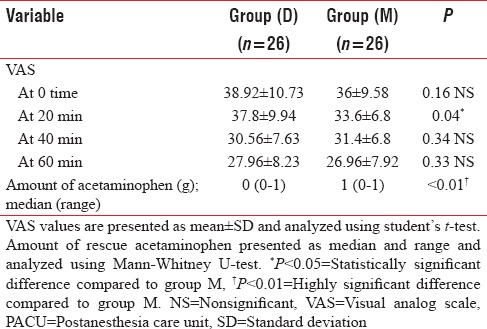

Statistical analysis of the mean values of VAS scores showed a significant decrease in group D intraoperatively at 5 and 10 min (P = 0.03 and 0.01, respectively) [Table 3] and postoperatively at 20 min (P = 0.04) [Table 4].

Table 3.

VAS and amount of rescue propofol during the procedure

Table 4.

VAS and amount of acetaminophen during PACU

Rescue sedation in the form of propofol 0.25 mg/kg was administered in both groups when required. A highly significant decrease (P < 0.01) in the total amount of propofol used during the procedure was evident in group D (median = 55 mg) in comparison with group M (median = 150 mg) [Table 3].

Postoperative requirements of rescue analgesia (IV acetaminophen) during PACU time were significantly less (P < 0.01) in group D (median = 0 g) when compared to group M (median = 1 g) [Table 4].

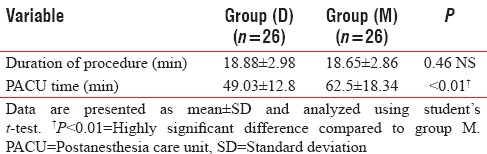

Although the difference in the duration of the procedure was insignificant between groups (P = 0.46), PACU stay was significantly shorter (P < 0.01) in group D (49.03 ± 12.8 min) than in group M (62.5 ± 18.34 min) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Duration of the procedure and PACU time

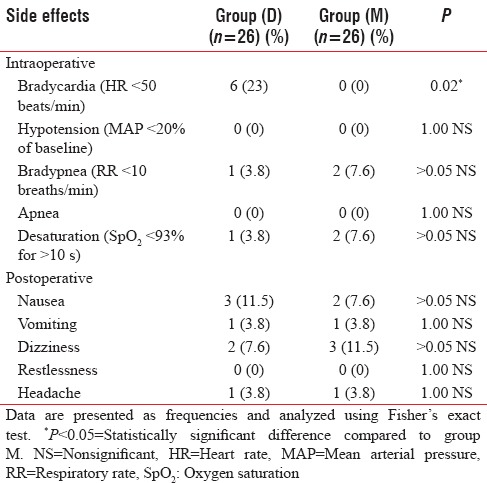

There were neither hypotension (MAP < 20% of baseline) nor apnea during the procedure, as well as 0% restlessness during the PACU time [Table 6].

Table 6.

Intra- and post-operative side effects

We observed six cases in group D (23%) who developed bradycardia (HR < 50 beats/min) during the procedure, which was statistically significant (P = 0.02) when compared to group M [Table 6].

During the procedure, bradypnea (RR < 10 breaths/min) and arterial oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <93%) have been noticed in only one case in group D and two cases in group M. This was statistically insignificant [Table 6].

Regarding postoperative side effects, group D had three cases of nausea (11.5%) and one case of vomiting (3.8%) compared with two nauseated patients (7.6%) and one recorded vomiting (3.8%) in group M. In group D, there were two reported cases of dizziness (7.6%) and one case of headache (3.8%) in comparison to three cases of dizziness (11.5%) and one case of headache (3.8%) in group M. There were no statistically significant differences between groups regarding all the studied postoperative side effects.

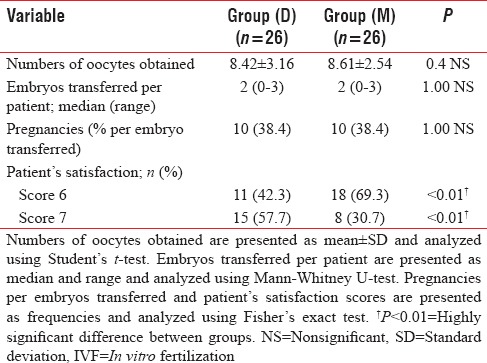

As illustrated in Table 7, there were no significant differences neither in the number of oocytes obtained nor embryos transferred, per patient. The percentage of pregnancies per embryo transferred was comparable between groups.

Table 7.

IVF outcomes and patient satisfaction scores

Finally, after completion of the procedure, patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher in group D than in group M (P < 0.1) [Table 7].

DISCUSSION

The perception of pain during oocyte retrieval is an important issue as patients may not remain stationary during the procedure when in pain, which can lead to an increased risk of injuries or damage to the surrounding blood vessels and bowel.[1,2]

Kwan et al. performed a study to assess the effectiveness and safety of different methods of conscious sedation and analgesia on pain relief and pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing transvaginal oocyte retrieval. They concluded that the evidence from 21 randomized controlled trials did not support one particular method or technique over another in providing effective conscious sedation and analgesia for pain relief during and after oocyte recovery. The simultaneous use of more than one method of sedation and pain relief resulted in better pain relief than one modality alone.[10]

In the present study, we compared the use of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam as a part of conscious sedation, in conjunction with paracervical block during oocyte retrieval, in terms of pain levels, intra- and post-operative side effects, and patient satisfaction. We found that dexmedetomidine provided better analgesia during and after the procedure with significantly less requirements for rescue propofol intraoperatively and acetaminophen postoperatively. In addition, dexmedetomidine offered not only a shorter PACU stay without significant side effects, but also better overall patient satisfaction scores.

Matsota et al. in their review article provided an overview of published data regarding the potential toxic effects of different anesthetic techniques (locoregional, general anesthesia, and MAC), different anesthetic agents, and alternative medicine approaches (principally acupuncture) on the IVF outcome. From their analysis, evidence of serious toxicity in humans is not well-established.[20]

The dose of midazolam 0.06 mg/kg was chosen based on the study by Eren et al.[21] that this dose is comparable to dexmedetomidine 1 mcg/kg in terms of sedation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing dexmedetomidine and midazolam for conscious sedation during oocyte retrieval in an IVF program. Candiotti et al. concluded that dexmedetomidine is a well-tolerated, safe, and effective primary sedative alternative to benzodiazepine/opioid combinations in patients undergoing MAC for a variety of surgical procedures;[15] which goes along with the results obtained in our study.

In this study, pain levels (assessed by VAS scores) in patients who received dexmedetomidine were significantly less than those noted in the midazolam group; at 5 and 10 min during the procedure and at 20 min during PACU time.

Candiotti et al. also concluded that with dexmedetomidine, there was a lower incidence of respiratory depression.[15] In our study, however, there was no statistically significant difference between the dexmedetomidine and the midazolam groups regarding the incidence of respiratory depression (one case of bradypnea [RR <10 breaths/min] and oxygen desaturation [SpO2 <93%] with dexmedetomidine and two cases in the midazolam group). All incidents were managed conservatively by simple oxygen facemask and improved at once.

Patient satisfaction was significantly higher in the dexmedetomidine group which confirms the results obtained by Candiotti et al.[15] The latter also reported significantly lower MAP and HR with dexmedetomidine as opposed to midazolam and fentanyl.[15] Although we reported six cases of bradycardia (HR <50 beats/min; treated with IV atropine 0.5 mg) with dexmedetomidine as opposed to nil in the midazolam group, there were no cases of hypotension in both groups.

Side effects such as dizziness, headache, nausea, and vomiting (managed conservatively by IV ondansetron 4 mg) were comparable statistically between groups.

Despite the small size of the patient groups studied, this preliminary experience points out the benefits of dexmedetomidine in conscious sedation. Future studies need to be carried out on a larger scale. Our study was extended only until the end of PACU time; further studies are required for long-term follow up to recognize potential effects on pregnancy outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Dexmedetomidine compared to midazolam, as a part of conscious sedation for oocyte retrieval during IVF program, offered a favorable analgesic technique during and after the procedure with significantly less requirements for rescue propofol intraoperatively and acetaminophen postoperatively. Furthermore, dexmedetomidine offered not only a shorter PACU stay without significant side effects, but also better overall patient satisfaction scores.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Ahmad Elnady, Consultant of Anesthesia for generous support and valuable viewpoints in language correction and evaluation of the study. The authors also thank all the staff of the fertility centre of Dr. Soliman Fakeeh Hospital, Jeddah, KSA for help with the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewin A, Laufer N, Rabinowitz R, Margalioth EJ, Bar I, Schenker JG. Ultrasonically guided oocyte collection under local anesthesia: The first choice method for in vitro fertilization-A comparative study with laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;46:257–61. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng EH, Tang OS, Chui DK, Ho PC. A prospective, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy of paracervical block in the pain relief during egg collection in IVF. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2783–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.11.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludwig AK, Glawatz M, Griesinger G, Diedrich K, Ludwig M. Perioperative and post-operative complications of transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval: Prospective study of >1000 oocyte retrievals. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3235–40. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng EH, Chui DK, Tang OS, Ho PC. Paracervical block with and without conscious sedation: A comparison of the pain levels during egg collection and the postoperative side effects. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:711–7. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01693-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stener-Victorin E. The pain-relieving effect of electro-acupuncture and conventional medical analgesic methods during oocyte retrieval: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:339–49. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasmin E, Dresner M, Balen A. Sedation and anaesthesia for transvaginal oocyte collection: An evaluation of practice in the UK. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2942–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilhelm W, Hammadeh ME, White PF, Georg T, Fleser R, Biedler A. General anesthesia versus monitored anesthesia care with remifentanil for assisted reproductive technologies: Effect on pregnancy rate. J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(01)00331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwan I, Bhattacharya S, Knox F, McNeil A. Conscious sedation and analgesia for oocyte retrieval during IVF procedures: A Cochrane review. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1672–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong JY, Kang IS, Koong MK, Yoon HJ, Jee YS, Park JW, et al. Preoperative anxiety and propofol requirement in conscious sedation for ovum retrieval. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:863–8. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwan I, Bhattacharya S, Knox F, McNeil A. Pain relief for women undergoing oocyte retrieval for assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD004829. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004829.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004–17. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey PL, Pace NL, Ashburn MA, Moll JW, East KA, Stanley TH. Frequent hypoxemia and apnea after sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:826–30. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao GP, Wong D, Groenewald C, McGalliard JN, Jones A, Ridges PJ. Local anaesthesia for vitreoretinal surgery: A case-control study of 200 cases. Eye (Lond) 1998;12:407–11. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gan TJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of medications used for moderate sedation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45:855–69. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candiotti KA, Bergese SD, Bokesch PM, Feldman MA, Wisemandle W, Bekker AY MAC Study Group. Monitored anesthesia care with dexmedetomidine: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:47–56. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181ae0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Grounds RM, Sarapohja T, Garratt C, Pocock SJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam or propofol for sedation during prolonged mechanical ventilation: Two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2012;307:1151–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gejervall AL, Stener-Victorin E, Möller A, Janson PO, Werner C, Bergh C. Electro-acupuncture versus conventional analgesia: A comparison of pain levels during oocyte aspiration and patients’ experiences of well-being after surgery. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:728–35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consales G, Chelazzi C, Rinaldi S, De Gaudio AR. Bispectral Index compared to Ramsay score for sedation monitoring in intensive care units. Minerva Anestesiol. 2006;72:329–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: A review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17:163–70. doi: 10.1179/jmt.2009.17.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsota P, Kaminioti E, Kostopanagiotou G. Anesthesia Related Toxic Effects on In Vitro Fertilization Outcome: Burden of Proof. Biomed Res Int 2015. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/475362. 475362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eren G, Cukurova Z, Demir G, Hergunsel O, Kozanhan B, Emir NS. Comparison of dexmedetomidine and three different doses of midazolam in preoperative sedation. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:367–72. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.83684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]