Abstract

Context:

Sparing of obturator nerve is a common problem encountered during transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) under spinal anesthesia.

Aims:

To evaluate and compare obturator nerve block (ONB) by two different techniques during TURBT.

Settings and Design:

This is prospective observational study.

Subjects and Methods:

Forty adult male patients from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Class I–IV planned to undergo TURBT under spinal anesthesia were divided into two groups of twenty each. In one group, ONB was performed with nerve locator. In other group, transvesical nerve block was performed with a cystoscope. The primary endpoints of this study were the occurrence of adductor reflex, ability to resect the tumor, and number of surgical interruptions. A number of transfusions required and bladder perforation were the secondary endpoints.

Results:

There was statistically significant difference between the groups for resection without adductor jerk, resection with a minimal jerk, and unresectable with high-intensity adductor jerk. Bleeding was observed in both groups and one bladder perforation was encountered.

Conclusions:

We conclude that ONB, when administered along with spinal anesthesia for TURBT, is extremely safe and effective method of anesthesia to overcome adductor contraction. ONB with nerve locator appears to be more effective method compared to the transvesical nerve block.

Keywords: Obturator nerve block, transurethral resection of bladder tumor, transvesical nerve block

INTRODUCTION

Urinary bladder masses are commonly performed under subarachnoid block which offers many advantages such as technical ease of performing the procedure, reduced risk of bleeding, and early recognition of bladder perforation. The only shortcoming with subarachnoid block is sparing of the obturator nerve with a potential complication of bladder rupture or injury secondary to adductor muscle contraction from obturator nerve stimulation (obturator reflex) during transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT).[1] The obturator nerve is derived from the 3rd to 4th lumbar nerves with a minor contribution from L2. The nerve descends on psoas muscle and lies deep in obturator canal (which is bordered by the obturator membrane, obturator muscles, and superior pubic ramus) from which it exists and divides into anterior and posterior branches. Anterior branch gives rise to articular branch to hip and innervates adductor muscles, whereas the posterior branch innervates deep adductor muscles and knee joint. The obturator nerve along with vessels pass from pelvic cavity where it runs close to prostatic urethra, bladder neck, and inferolateral bladder wall and exit to thigh through canal where it can be easily blocked.[2]

The key objective of this study was to compare the occurrence of adductor jerk with the ability to resect bladder tumor by anatomic landmark-guided obturator nerve block (ONB) with a nerve locator and transvesical nerve block with a cystoscope.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Selection criteria and randomization

After the Institution Ethical Committee approval and informed patient consent, forty patients with age range 50–70 years of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Class I–IV scheduled for elective urinary bladder tumor resection under subarachnoid block were randomly enrolled in this study. Patients with coagulopathy, infection, scar, or surgery at lumber spine and pubic region known hypersensitivity to the local anesthetic agent were excluded from the study.

The randomization was based on computer-generated code for forty patients and was assigned to one of two groups as follows.

Both the groups received 10 ml 2% preservative free lignocaine along with 5 ml 0.5% preservative free bupivacaine. The drugs were given as per the groups:

Group O: The drugs were injected after locating obturator nerve with nerve locator

Group I: The drugs were injected transurethrally into the urinary bladder.

Preoperative assessment included ultrasonography and a computerized scan of the urinary bladder to decide the side to which obturator nerve was to be blocked.

Study procedure and anesthetic technique

An intravenous catheter was secured and patients were monitored for heart rate, noninvasive blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. All patients after aseptic preparation received subarachnoid block in lumber 3–4 or 4–5 space in sitting position. About 2.5 ml of heavy 0.5% bupivacaine was injected into subarachnoid space. After the completion of the block, patients were laid in the supine position and subsequently waited for 5 min for fixation of drug and assessed for sensorimotor block. Further procedure was performed as per the group allocation. In Group O, patients pubic and upper thigh was aseptically prepared and a 8 cm long block needle attached to nerve locator (Innervator 272 Fisher and Paykel) set at 2.0 mA current was inserted 1.5 cm lateral and perpendicular inferior to pubic tubercle to hit ramus and redirect needle caudally and medially to enter obturator foramen where obturator canal houses the nerve. Muscle contractions when visible on the medial aspect of the thigh, the requisite drug were then injected to block the obturator nerve once contractions could be seen at 0.5 mA current level.

In the other group, after passing cystoscope into bladder transurethrally, the requisite drug was instilled into the urinary bladder with 30° Trendelenberg's position along with lateral tilt so that the instilled drug does not wash out and effectively blocks the obturator nerve of the same side.

For both the groups, a waiting period was 20 min was allowed for the full effect of the block and then resection was allowed to perform. Monopolar cautery was used to resect the tumor with the loop and the setting was adjusted between 75–90 W for cutting and 55–75 W for coagulation.

During the operative procedure, the primary endpoint of the study was resectability of the tumor whether hampered or unhampered, adductor reflex defined as jerky adduction, and eternal rotation of the thigh at hip joint and number of interruptions. Bleeding and bladder perforation were the secondary endpoints. All patients who had unresectability due to adductor jerk were managed under general anesthesia with muscle relaxation.

The sample size was calculated based on 80% power and 95% significance for adductor jerk and 25% incidence for monopolar cautery system. Assuming a dropout of 5%, a final size was estimated to be 42 patients. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 (Neon laboratories). The data were tabulated as a mean ± standard deviation and significance was analyzed by using independent sample t-test for continuous variables and categorical variables were compared with Chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

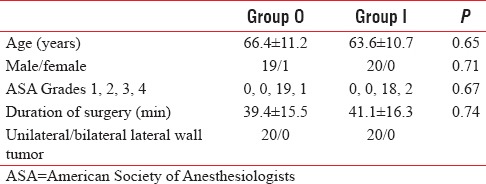

Of the forty patients included in this study, majority were males with only one female patient who was in Group O. The demographic profile for the two groups was statistically insignificant for different parameters [Table 1]. The duration of surgery was comparable with P = 0.74.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

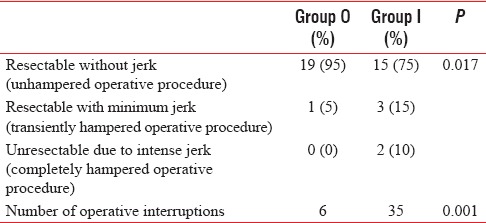

There was a significant difference for the ability to resect the tumor without any adductor reflex for the two groups (P = 0.017) [Table 2]. More patients were able to undergo resection without any jerk in Group O. This difference could be attributed to more number of patients who demonstrated jerk in the Group I. Unresectability due to jerk was higher in the Group I.

Table 2.

Resectability of tumor and interruptions

DISCUSSION

TURBT is widely used surgical technique for both diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer. Usually performed under subarachnoid block, TURBT cannot be carried out effectively due to sparing of obturator nerve which courses on the lateral wall of bladder where it can be easily get stimulated by the electrical current passed through the loop during resection with an intense involuntary response from adductors (adductor longus, brevis, magnus, gracilis) and external rotation (obturator externus) of hip. Adductor jerk or obturator reflex is associated with a serious injury such as vessel wall laceration with profuse bleeding, bladder wall tear or perforation, and even incomplete resection due to frequent distractions and interruptions to the operating surgeon.[3]

Several methods have been used to abolish the reflex such as reducing the diathermy power and using bipolar instead of monopolar cautery but none been completely successful.

Venkatramani et al.[4] compared monopolar with bipolar cauterization for TURBT and concluded that bipolar TURBT was not superior to unipolar TURBT with respect to obturator jerk, bladder perforation, and hemostasis are concerned although Gupta et al.[5] eliminated nerve stimulation with the use of current of power as low as 50 W and 40 W for cutting and coagulation, but these settings have been reported to be too low for satisfactory resection.

Various other strategies, such as partial filling of the bladder during resection, modification in the surgical procedure such as resecting the tumor on thinner slices, laser resection, reverse in polarity of electric current, change in site of inactive electrode and using general anesthesia with muscle relaxants, have been adapted to avoid complications during surgery but with wide-ranging achievement.[6,7] Laser systems are luxurious and not easily available at many centers. General anesthesia is not a suitable option as it is associated with pulmonary complication which is so prevalent in this age group.

ONB combined subarachnoid anesthesia can only be an effective modality in the TURBT which can easily be accomplished. Various methods have been described in literature to block obturator nerve. Prentiss et al.[8] and later Parks and Kennedy[9] described nerve stimulation technique with a success rate between 83.8% and 85.7%. The success rate with nerve stimulation was very high in our study (95%). More recent studies have reported that the use of sonography is associated with higher success rates of 97.2% in ultrasound-guided ONB procedures.[10,11] This is slightly higher than nerve stimulation technique. According to Augspurger and Donohue,[12] effectiveness of abolishing obturator jerk with blind anatomic approach was 83.8% which is lower to nerve stimulation and ultrasound-guided techniques described above. As per Gasparich et al.[13] and Kobayashi et al.[14] with nerve stimulation, the effectiveness reaches between 89.4% and 100%.

Gasparich et al.[13] used the nerve stimulation approach with 0.5 mA, and 3–4 ml of 1% lignocaine with a success rate of 100%, while Kobayashi et al.[14] also used nerve stimulation with 0.5 mA and injected 7–40 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine with a success rate of 89.4%. Hence, concentration and not volume determine the success rate of the block which may hold true even for sonographic technique.

Kuo[15] and Khorrami et al.[16] described the transvesical blockade of obturator nerve with 10 ml 1% lignocaine injected through cystoscope along with spinal anesthesia (thirty patients) and compared it with spinal anesthesia only group (thirty patients). In the intervention group, 34 ONB were performed. They observed a significant jerk in the control group (16.5%) compared to the intervention group (3%). In contrast, more jerks have been reported in our study which could be due to impeded penetration of local anesthetic through the thicker bladder wall.

Malik et al.[17] reported transfusion in 25% of patients (11/42) after TURBT. In our study, both the groups required transfusions with fewer in the Group O compared to Group I [Table 3].

Table 3.

Resectability of tumor and interruptions

Dick et al.[18] have reported 13% incidence of hemorrhage while Collado et al.[1] have reported 3.4% incidence of blood transfusion. Lower preoperative hemoglobin levels may be responsible for more transfusions in our study. Only one bladder perforation was observed in our study. Literature search reveal incidence varies from 0.9% to 5%.[19]

CONCLUSIONS

ONB is a safe and effective method to abolish adductor jerk which may otherwise certainly occur with subarachnoid block for TURBT. Thus, it has become an essential component of spinal anesthesia for TURBT.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collado A, Chéchile GE, Salvador J, Vicente J. Early complications of endoscopic treatment for superficial bladder tumors. J Urol. 2000;164:1529–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berberoglu M, Uz A, Ozmen MM, Bozkurt MC, Erkuran C, Taner S, et al. Corona mortis: An anatomic study in seven cadavers and an endoscopic study in 28 patients. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:72–5. doi: 10.1007/s004640000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thallaj A, Rabah D. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided obturator nerve block in transurethral surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:42–4. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkatramani V, Panda A, Manojkumar R, Kekre NS. Monopolar versus bipolar transurethral resection of bladder tumors: A single center, parallel arm, randomized, controlled trial. J Urol. 2014;191:1703–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta NP, Saini AK, Dogra PN, Seth A, Kumar R. Bipolar energy for transurethral resection of bladder tumours at low-power settings: Initial experience. BJU Int. 2011;108:553–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moningi S, Durga P, Ramachandran G, Murthy PV, Chilumala RR. Comparison of inguinal versus classic approach for obturator nerve block in patients undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumors under spinal anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30:41–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.125702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer MW, Bach T, Wolters M, Imkamp F, Gross AJ, Kuczyk MA, et al. Current evidence for transurethral laser therapy of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol. 2011;29:433–42. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prentiss RJ, Harvey GW, Bethard WF, Boatwright DE, Pennington RD. Massive adductor muscle contraction in transurethral surgery: Cause and prevention; development of electrical circuitry. J Urol. 1965;93:263–71. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks CR, Kennedy WF., Jr Obturator nerve block: A simplified approach. Anesthesiology. 1967;28:775–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196707000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Jeong CW, Lee HJ, Yoon MH, Kim WM. Ultrasound guided obturator nerve block: A single interfascial injection technique. J Anesth. 2011;25:923–6. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1228-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akkaya T, Ozturk E, Comert A, Ates Y, Gumus H, Ozturk H, et al. Ultrasound-guided obturator nerve block: A sonoanatomic study of a new methodologic approach. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1037–41. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181966f03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Augspurger RR, Donohue RE. Prevention of obturator nerve stimulation during transurethral surgery. J Urol. 1980;123:170–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55837-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasparich JP, Mason JT, Berger RE. Use of nerve stimulator for simple and accurate obturator nerve block before transurethral resection. J Urol. 1984;132:291–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi M, Takeyoshi S, Takiyama R, Seki E, Tsuno S, Hidaka S, et al. A report of 107 cases of obturator nerve block. Jpn J Anesth. 1991;40:1138–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo JY. Prevention of obturator jerk during transurethral resection of bladder tumor. JTUA. 2008;19:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khorrami MH, Javid A, Saryazdi H, Javid M. Transvesical blockade of the obturator nerve to prevent adductor contraction in transurethral bladder surgery. J Endourol. 2010;24:1651–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik MA, Nawaz S, Khalid M, Ahmad A, Ahmad M, Shahzad S, et al. Obturator nerve block (ONB) in transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) JUMDC. 2013;4:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dick A, Barnes R, Hadley H, Bergman RT, Ninan CA. Complications of transurethral resection of bladder tumors: Prevention, recognition and treatment. J Urol. 1980;124:810–1. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traxer O, Pasqui F, Gattegno B, Pearle MS. Technique and complications of transurethral surgery for bladder tumours. BJU Int. 2004;94:492–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]