Abstract

Context:

Supraglottic airway devices can act as an alternative to endotracheal intubation in both normal and difficult airway. LMA Proseal (P-LMA) and LMA Supreme (S-LMA) alongwith acting as effective ventilating device, provide port for gastric drainage.

Aim:

The objective of this study was to compare the two devices for effective ventilation and complications.

Setting and Design:

A prospective, randomized, single-blinded study was conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Methods: 100 patients of ASA grade I–II undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthesia were included after ethical committee clearance and written consent. Patients were randomly allocated size 4 P-LMA (Group P) or S-LMA (Group S) (50 patients in each group). Insertion attempt, insertion time, oropharyngeal leak pressure (OLP) and complications were compared.

Results:

There was no difference demographically. The first insertion attempts were successful in 92% with P-LMA and 96% with S-LMA. Insertion time was faster in S-LMA. The mean OLP was 24.04 cmH2O in Group P and 20.05 cmH2O in Group S. Complications were cough, mild blood staining.

Conclusion:

Both can act as an effective ventilatory devices. But where LMA Proseal provides a more effective glottic seal by having a greater OLP, single use LMA Supreme provides acceptable glottic seal with easier and faster insertion, therefore, it can be accepted as better alternative to LMA Proseal.

Keywords: Laryngeal mask airway, laryngeal mask airway Proseal, laryngeal mask airway Supreme, oropharyngeal leak pressure

INTRODUCTION

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) has been considered the conventional gold standard technique of securing the airway during general anesthesia until date.[1]

Dr. Archie Brain revolutionized the airway management with the introduction of supraglottic devices which are now being incorporated into routine as well as in American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) difficult airways algorithm.[2]

After various modifications, Proseal laryngeal mask airway (P-LMA), a reusable device was invented which has a specially designed cuff to provide a better and more effective seal than classic LMA along with the presence of gastric drainage port which can be considered as a potential protection against aspiration.[3,4] Simultaneously, it also reduces the likelihood of throat irritation and stimulation, and reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting by as much as 40% compared to an ETI.[5]

LMA Supreme (S-LMA), a single use, latex free device which is made of polyvinyl chloride, has an anatomically shaped airway tube which expedites easy insertion, without the need to place fingers in the patient's mouth or using an introducer tool for insertion. It is unique in its own way as it integrates advantages of P-LMA[4] (like high seal cuff for effective ventilation, gastric drainage port for airway protection, and bite block for preventing airway obstruction), the LMA-Fastrach[6] (fixed curve tube which aids in insertion) and the LMA Unique[7] (single use, preventing the risks of disease transmission).

The main aim of this study was to compare the clinical efficacy of P-LMA and S-LMA in patients undergoing elective surgeries under general anesthesia.

Patient selection

After obtaining approval from ethical committee, 100 patients were chosen who were scheduled to undergo elective surgeries under general anesthesia. The duration of this study was 1 year. Written informed consents were taken from the patients. The inclusion criteria were patients with ASA physical status I–II, aged 18–50 years. Patients were excluded if they had a mouth opening <2 cm, anticipated difficult airway, poor general health, body mass index >30 kg/m2, upper respiratory tract infection, increased risk of aspiration (gastroesophageal reflex disorder, hiatus hernia, and pregnancy), cervical spine fracture or instability, and history of allergy to one or more drugs and latex. The patients were randomly divided into two groups (according to a computer generated plan on www.randomisation.com) – 50 patients to the Supreme group (Group S) and 50 patients to the Proseal group (Group P). Sample size was calculated with the assumption of at least of 30% possible difference between the two groups. Hence, 50 patients were allotted into each group to obtain an alpha error of 5% and statistical power of 80% and also to include the dropouts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A thorough preanesthetic check-up was performed 1 day before the day of the surgery. All patients were given tablet alprazolam 0.5 mg orally at bedtime on the previous night of surgery and were kept nil per oral for 12 h before surgery. After the patient was shifted to operation theater, standard monitors such as pulse oximeter, noninvasive blood pressure, and 3 lead electrocardiogram were connected. Intravenous (IV) access was gained with 18-gauge cannula and Ringer's lactate infusion was started. Patient were given injection glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg IV, injection midazolam 0.05 mg/kg IV, injection tramadol 1 mg/kg IV, injection ondansetron 4 mg IV, injection ranitidine 40 mg IV, and then preoxygenated with 100% oxygen for 3 min. Anesthesia was induced with injection propofol 2.5 mg/kg IV and injection vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg IV was used to achieve neuromuscular blockade.

Patients were ventilated and after the adequate depth of anesthesia had been achieved, each device was inserted after lubrication of posterior surface with water-based jelly. S-LMA was inserted using a smooth circular rotating movement until definite resistance was felt when the device was in the hypopharynx. This technique was used as suggested by the manufacturer.[8] P-LMA was inserted using the index finger and advanced into the hypopharynx until resistance was felt.[9]

In Group P, size 4 P-LMA was inserted which was according to the patient's weight and cuff was inflated to 30 ml as recommended by the manufacturer. For patients of Group S, S-LMA size 4 was inserted according to the weight and cuff was inflated to 45 ml.

An effective airway was confirmed by bilateral symmetrical chest movement on manual ventilation, square wave capnography, the absence of audible leak of gas, and lack of gastric insufflations. If it was not possible to insert the device or ventilate through it, two more attempts of insertion were allowed. If placement failed even after three attempts, the airway was secured through other airway device as suitable and the case was excluded from our study. After securing the device in place, a well lubricated 16 F gastric tube was introduced into the stomach through the gastric drainage port.

Patients were maintained with nitrous oxide, oxygen mixture (N2O: O2 70:30) and isoflurane 1% connected to Drager Fabius machine and put on volume mode and intermittent boluses of vecuronium were administered IV. Patient also received paracetamol infusion IV 15 mg/kg intraoperatively. A single blinded assistant collected data on the number of attempts for successful LMA insertion, the time taken and the ease of LMA insertion. The oropharyngeal leak pressures (OLPs) were determined by closing the expiratory valve of the circle system at a fixed gas flow of 3 L/min. The OLP was the pressure in the circuit when an audible noise was heard over the mouth. For safety concerns, the maximal allowable OLP was 40 cm H2O.

At the end of operation, anesthetic agents were discontinued and neuromuscular block was reversed with injection glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg IV, injection neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg IV allowing smooth recovery of consciousness. The device was removed after the patient regained consciousness and breathed spontaneously and responded to the verbal command to open the eye. Blood staining of the device, trauma to the mouth, tooth or pharynx, and sore throat were noted.

RESULTS

The study population consisted of 100 ASA I–II, patients posted for elective surgery under general anesthesia. They were divided into two groups of 50 each randomly.

All patients were included in the statistical analysis and analysis was performed with GraphPad InStat® software (GraphPad Software, Inc., 7825 Fay Avenue, Suite 230, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA) using Student's unpaired t-test for quantitative data and Fisher exact test or Chi-square test for qualitative data. P value was calculated and interpreted. The value of P > 0.05 was considered not significant, P < 0.05 was considered significant, and P < 0.0001 was highly significant.

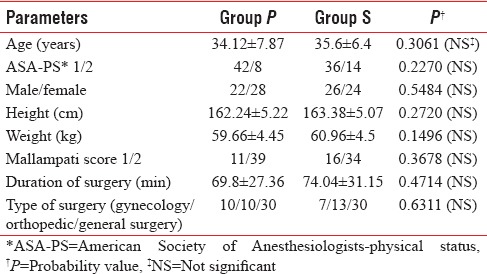

There were no differences between the groups regarding age, gender, weight, height, type, and duration of surgery. All the data were statistically insignificant and thus comparable [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

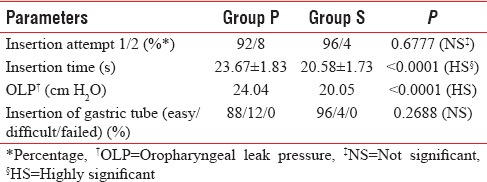

During insertion and establishment of the airway, the first insertion attempts were successful in 46 patients (92%) with P-LMA and in 48 patients (96%) with S-LMA. Insertion time was slightly faster in S-LMA group which was significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Insertion parameters and oropharyngeal leak pressure measurements in two groups

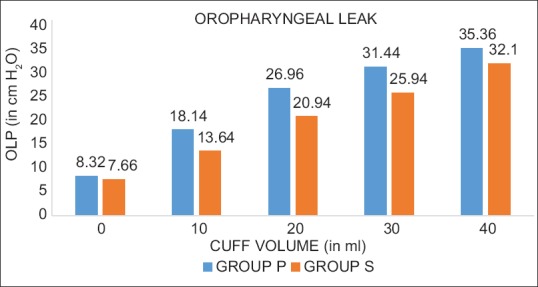

The mean OLP in our study was 24.04 cm H2O in the Group P and 20.05 cm H2O in Group S which was significant [Table 2]. It was found that OLP for Group P was significantly higher at all cuff volumes with respect to Group S [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Bar diagram shows the distribution of mean oropharyngeal leak pressure for both groups with increasing cuff volume.

In this study, the intra-cuff pressures were significantly higher in P-LMA in comparison to S-LMA at all cuff volumes of inflation range.

Gastric tube insertion was easier in Group S 96% as compared to 88% in Group P [Table 2].

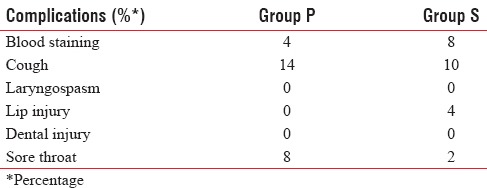

There were no differences between P-LMA and S-LMA with respect to doses of induction agents. Intraoperative complications were similar for both groups. The most frequent complication noted was cough and slight blood staining in both the groups. Minor lip injury occurred in two patients in Group S. Cough and sore throat were mainly seen in Group P as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Complications between the two groups

DISCUSSION

In our study, both the P-LMA and S-LMA were successfully inserted and each patient was provided an effective airway with a low rate of complications.

This study was undertaken to compare the clinical efficacy of P-LMA and S-LMA for ease of insertion and effective airway seal pressures in anesthetized adult patients.

A total of 100 patients belonging to ASA status I or II between 18 and 50 years of age with comparable demographic data presented for elective surgery under general anesthesia were enrolled in this study.

In this study, the first attempt of insertion was similar (P-LMA 92%; S-LMA 96%). Guided insertion was always successful following failed digital insertion. The mean duration of insertion with the P-LMA was longer in comparison to S-LMA (23.67 ± 1.83 vs. 20.58 ± 1.73 s) which makes S-LMA effective in scenarios requiring the urgent need for ventilation hence more effective in its life-saving role in difficult airway.

The specially designed airway tube (LMA evolution curve) which has an anatomical resemblance allows for smoother and easier insertion of S-LMA and thin wedge-shaped leading edge which gives it an edge over other LMAs which conventionally require digital insertion or use of the introducer.

The difficulty in inserting the Proseal may be due to the shape of its larger, deeper, and softer bowl with the gastric drainage port forming the nonlinear leading edge. The higher success rate was also associated with a lesser insertion time with S-LMA than with P-LMA. These findings of our study have been supported by other studies.

Hosten et al.[10] reported the first attempt success rates of 93% with both S-LMA and P-LMA. Mean airway device insertion time was significantly shorter with S-LMA than with P-LMA (12.5 ± 4.1 s vs. 15.6 ± 6.0 s; P = 0.02) in 60 adults undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Seet et al.,[11] also compared the safety and efficacy of S-LMA with P-LMA. The success rate of the first attempt insertion was higher for the S-LMA than for the P-LMA (98% and 88%, respectively) in 99 nonparalyzed adult patients which confirm our data.

OLP measurements are commonly performed with LMA to assess the degree of airway protection, its feasibility for using them for positive pressure ventilation, and for confirmation of successful supraglottic airway placement.[12] Inadequate placement will increase the leak and the purpose of using LMA as an effective ventilatory device will not be fulfilled.

In our study, the mean OLP was significantly higher in the P-LMA in comparison to S-LMA (24.04 vs. 20.05 cm of H2O) suggesting that the P-LMA is a more effective ventilatory device as OLP is considered as a marker of efficacy and safety while using LMA devices.

Our data are consistent with three randomized trials comparing the two devices. A study by Eschertzhuber et al.[13] observed that the OLP was lower in the Group S by 4–8 cm H2O than in the Group P in a crossover trial in 93 female patients undergoing surgery with a size 4 S-LMA. Lee et al.[14] reported a similar difference between the two devices (31.7 vs. 27.9 cm H2O) in a study on 70 female patients undergoing laparoscopic gynecological procedures. Seet et al.[11] found mean OLP with the S-LMA was 21 ± 5 cm H2O (95% confidence interval 20–22). This was significantly lower than that of the P-LMA, 25 ± 6 cm H2O (95% confidence interval 23–27; P < 0.001).

The lower OLP for the S-LMA is probably related to the less elastic and less moldable property of the polyvinyl chloride single cuff. The Proseal has a double-cuff design and is made of silicone rubber with higher elasticity and is more ideal for molding. This may result in a better glottic seal. In addition, the lower OLP with the Supreme may be due to movement of the semirigid curved airway tube.

Raised intracuff pressures in LMA are associated with increased incidence of pharyngolaryngeal morbidity such as sore throat. In this study, the intracuff pressures were significantly higher in P-LMA in comparison to S-LMA at all cuff volumes of inflation range which is supported by other studies.[15] Intracuff pressure should be kept according to the manufacturer's instruction. In P-LMA, other studies indicate that intracuff pressure increases progressively during the surgery in which nitrous oxide is used with oxygen which might increase the pharyngolaryngeal morbidity.[16] S-LMA is devoid of this effect which makes it hassle free to use in such cases and gives it an another edge over P-LMA.

Gastric drain insertion was accomplished in 100% patients in both the groups and was successful in the first attempt in 88% in P-LMA group in comparison to 96% in S-LMA group the results of which are similar to those found by a study by Hosten et al.[10] where the first attempt success rates for the drainage tube insertion were 93% for P-LMA and 100% for S-LMA 100%. If the gastric tube is easily passed, it indirectly confirms correct placement of the supraglottic device.[17] Incorporation of gastric drainage port has led to the use of such devices easily as aspiration of gastric contents will reduce the intragastric volume considerably and ultimately reducing the risk of aspiration.

P-LMA is a reusable version which can be safely used up to 40 times after properly autoclaving it. Improper sterilization may predispose the patient to iatrogenic infections. In such scenarios, S-LMA has the advantage of being a single use device. There is an increased tendency toward using single-use devices due to the awareness that protein and bacteria persist on surgical and anesthetic instruments following the decontamination and sterilization process. The S-LMA can reduce or even eliminate the fear that patients may contract iatrogenic infections such as variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, HIV and hepatitis B or C[11,18] which makes it a perfect option in this regard.

S-LMA can provide acceptable if not as high glottic seal as that provided by P-LMA but features of anatomically shaped airway tube and inclusion of gastric drain makes it an acceptable alternative for ventilation. Being made of polyvinyl chloride, it also eliminates the chances of increasing cuff pressure in the presence of nitrous use. Faster insertion time along with more ease in introduction makes it a favorable device for use. In this era, advances for providing adequate ventilation while minimizing the adverse outcomes of conventional intubation have led us to use this family of supraglottic airway devices frequently.

Both these devices provide greater patient's as well as anesthesiologist's satisfaction thereby leading to their incorporation in our routine practice.

CONCLUSION

Both the devices P-LMA and S-LMA can act as ventilatory devices but where P-LMA provides a more effective glottic seal, S-LMA provides acceptable glottic seal with easier and faster insertion and being a single use device, reduces the chances of transmission of infections, and, therefore, can be considered as a better alternative to P-LMA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Silchar Medical College and the patients enrolled in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rushman GB, Davies NJ, Cashman JN. Intubation and ventilation. In: Rushman GB, Davies NJ, Cashman JN, editors. Lee's Synopsis of Anaesthesia. Great Britain: MPG; 1999. pp. 246–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Young WL. Miller's Anesthesia. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2015. pp. 1661–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mark DA. Protection from aspiration with the LMA-ProSeal after vomiting: A case report. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:78–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03020192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brain AI, Verghese C, Strube PJ. The LMA ‘ProSeal’ – A laryngeal mask with an oesophageal vent. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:650–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/84.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hohlrieder M, Brimacombe J, von Goedecke A, Keller C. Postoperative nausea, vomiting, airway morbidity, and analgesic requirements are lower for the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway than the tracheal tube in females undergoing breast and gynaecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:576–80. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brain AI, Verghese C, Addy EV, Kapila A. The intubating laryngeal mask. I: Development of a new device for intubation of the trachea. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:699–703. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Morris R, Mecklem D. A comparison of the disposable versus the reusable laryngeal mask airway in paralyzed adult patients. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:921–4. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199810000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Laryngeal Mask Company Ltd. LMATM: LMA SupremeTM. Instruction Manual. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Intavent Orthofix Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.LMA ProSeal instruction manual. Maidenhead: Intavent Orthofix; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosten T, Yildiz TS, Kus A, Solak M, Toker K. Comparison of supreme laryngeal mask airway and ProSeal laryngeal mask airway during cholecystectomy. Balkan Med J. 2012;29:314–9. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2012.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seet E, Rajeev S, Firoz T, Yousaf F, Wong J, Wong DT, et al. Safety and efficacy of laryngeal mask airway supreme versus laryngeal mask airway ProSeal: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:602–7. doi: 10.1097/eja.0b013e32833679e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller C, Brimacombe JR, Keller K, Morris R. Comparison of four methods for assessing airway sealing pressure with the laryngeal mask airway in adult patients. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:286–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eschertzhuber S, Brimacombe J, Hohlrieder M, Keller C. The laryngeal mask airway Supreme – A single use laryngeal mask airway with an oesophageal vent. A randomised, cross-over study with the laryngeal mask airway ProSeal in paralysed, anaesthetised patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AK, Tey JB, Lim Y, Sia AT. Comparison of the single-use LMA supreme with the reusable ProSeal LMA for anaesthesia in gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:815–9. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brimacombe JR, Brain AI, Berry AM. The Laryngeal Mask Airway: A Review and Practical Guide. London: WB. Saunders Company Ltd; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma B, Gupta R, Sehgal R, Koul A, Sood J. ProSeal™ laryngeal mask airway cuff pressure changes with and without use of nitrous oxide during laparoscopic surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:47–51. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.105795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Berry A. Assessing ProSeal laryngeal mask positioning: Suprasternal notch test. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1375. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200205000-00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowley E, Dingwall R. The use of single-use devices in anaesthesia: Balancing the risks to patient safety. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:569–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.04995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]