Abstract

Background:

Radial artery cannulation is a skillful procedure. An experienced anesthesiologist might also face difficulty in cannulating a feeble radial pulse.

Aim:

The purpose of the study was to determine whether periradial subcutaneous administration of papaverine results in effective vasodilation and improvement in the palpability score of radial artery.

Settings and Design:

Prospective, double-blinded trial.

Methodology:

Thirty patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery were enrolled in the study. 30 mg of papaverine with 1 ml of 2% lignocaine and 3 ml of normal saline were injected subcutaneously 1–2 cm proximal to styloid process of the radius. Radial artery diameter before and after 20 min of injection papaverine was measured using ultrasonography. The palpability of the radial pulse was also determined before the injection of papaverine and 20 min later. Patients were monitored for hemodynamics and any complications were noted.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Student's t-test for paired data.

Results:

Radial artery diameter increased significantly (P < 0.0001), and the pulse palpability score also showed statistically significant improvement (P < 0.0001) after periradial subcutaneous administration of papaverine. There was no statistically significant difference in heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure before and after papaverine injection. No complications were noted in 24 h of follow-up.

Conclusion:

Periradial subcutaneous administration of papaverine significantly increased the radial artery diameter and pulse palpability score, which had an impact on ease of radial artery cannulation essential for hemodynamic monitoring in cardiac surgical patients.

Keywords: Papaverine, pulse palpability score, radial artery

INTRODUCTION

Invasive arterial cannulation is routinely used for continuous, real-time blood pressure monitoring during perioperative cardiac surgical patients. The intra-arterial catheters are usually inserted percutaneously into radial, femoral, and other superficial arteries. Radial artery is choosen since it is easily accessible for cannulation and is associated with lesser complications compared to femoral artery cannulation.[1]

However, radial artery is more prone for arterial spasm during and after cannulation, which adversely affects the progress of the procedure. This is due to smaller caliber and a large muscular media with a higher receptor-mediated vasomotion compared with other similar arteries.[2] Spasm before cannulation of radial artery can be due to repeated attempts to canulate or after an initial failed puncture, which leads to reduction in pulse volume and/or even complete loss of radial pulse. This results in abandoning the procedure and switching over to other alternative arterial access.[3] Various vasodilators such as nitrates,[4] calcium channel blockers[5] are known to cause vasodilatation and reduce spasm of radial artery.

Papaverine is an alkaloid obtained from opium or prepared synthetically, having vasodilator property. By the virtue of its vasodilator property, intra-arterial papaverine has been used to treat severe radial artery spasm during coronary angiography.[6] Papaverine, when administered by different routes, resulted in increased internal mammary artery blood flow during coronary artery bypass surgeries.[7] Parenteral administration of papaverine is known to cause undesirable hypotension and also there has been limited literature on subcutaneous route of administration of papaverine.

Hence, the study was done to determine the effects of periradial administration of papaverine on the diameter and palpability of radial artery.

Methodology

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure. The study was conducted over a period of 6 months, which was a prospective, nonrandomized double-blinded trial. Total of Thirty patients, age >40 years, scheduled for elective cardiac surgery were included in the study. Patients with pure stenotic valve lesions, negative modified Allen test, atrioventricular block, glaucoma, altered liver function, unstable hemodynamics, emergency surgeries, and peripheral vascular disease were excluded from the study.

All patients were examined in the supine position with use of a commercially available ultrasound system (Philips HD7-XE, Bothell, Washington, USA 98021). Images were acquired with use of a 12-MHz linear transducer. All patients radial artery of nondominant hand were assessed for course and quality of the artery using USG before injection of the test drug. The diameter of radial artery was measured at the wrist, 1–2 cm proximal to styloid process of radius bone in the longitudinal plane during the systolic period. The segments with clear anterior and posterior intimal borders were selected for continuous two-dimensional grayscale imaging. All the baseline ultrasound measurements were performed by a single operator, who was blinded to the ingredients of the injection. Later anesthesiologist injected periradial subcutaneous injection of total 5 ml solution which contained 30 mg (1 ml) of papaverine (30 mg/ml, Retort Laboratories, India) +1 ml of 2% lignocaine (Xylocard) +3 ml of normal saline under ultrasonographic guidance using 24-gauge hypodermic needle (Dispo Van, Faridabad, India). The injections were performed as single, slow injection at sites 1 cm proximal to the styloid process of the radial bone. Luminal diameters were measured 20 min after the injection by the same ultrasound operator, still blinded to the study. Heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) were recorded before papaverine injection and 20 min later. The palpability of pulse (i.e., pulse palpability score) in the radial artery before injection was scored on a scale of 1–3 as follows: 1 - weak; 2 - easily palpable; and 3 - strongly palpable. Pulse palpability score was again noted after 20 min of periradial subcutaneous injection. Pulse palpability score was done by another person who was also blinded for the study. This was followed by radial artery cannulation by the same anesthesiologist. All patients HR, SBP, DBP, and MAP were monitored for the next 2 h and any side effects were noted till the next 24 h.

Statistical analysis

Performed using MedCalc software version 12.2.1.0. (Ostend, Belgium). The sample size was calculated based on the previous study – effect of subcutaneous nitroglycerin (NTG) on radial artery diameter and considering alpha error of 0.05 and beta error of 0.05 a minimum sample size of 21 was required. As there are no studies on the effect of subcutaneous papaverine effect on radial artery diameter, a sample size of 30 was chosen.

Changes in radial artery diameter were compared by means of Student's t-test for paired data before and 20 min after periradial subcutaneous injection of papaverine. A two-tailed probability level of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

A total of thirty patients were enrolled in the study. There were 9 females and 21 male patients. Total of 16 patients were scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft, 5 for mitral valve replacement, 4 for aortic valve replacement, 2 for atrial septal defect closure, and 3 for double valve replacement.

The hemodynamic parameters - HR, SBP, DBP, and MAP measured before periradial injection of papaverine showed no statistical significance when compared to 20 min after periradial injection of papaverine [Table 1].

Table 1.

Heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and mean arterial pressure measured before and 20 min after periradial administration of papaverine injection

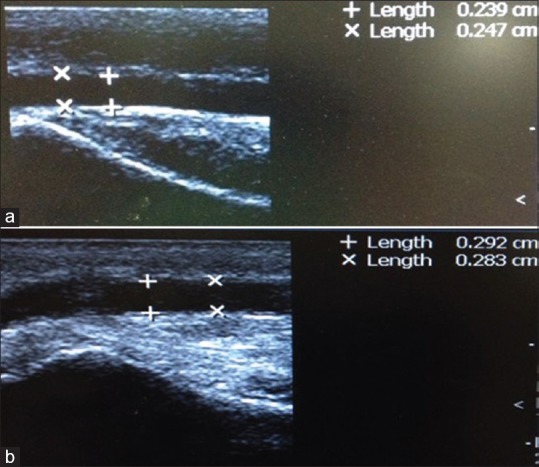

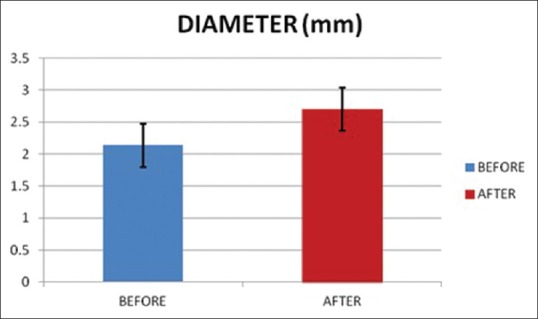

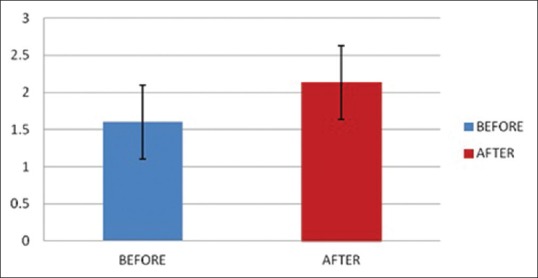

Periradial subcutaneous injection of papaverine had a significant effect on diameter [Figures 1 and 2] and pulse palpability score [Figure 3] with a statistically significant increase in the radial artery diameter (P < 0.0001) and pulse palpability score (P < 0.0001) 20 min after the injection of periradial papaverine [Table 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Intraluminal radial artery diameter before papaverine injection. (b) Intraluminal radial artery diameter after papaverine injection.

Figure 2.

Radial artery diameter before and after papaverine injection.

Figure 3.

Pulse palpability score before and after papaverine injection.

Table 2.

Radial artery diameter and pulse palpability score before and 20 min after periradial administration of papaverine injection

Radial artery was successfully cannulated in all patients. None of the patients had any complication during or after the procedure.

DISCUSSION

During induction arterial access for hemodynamic monitoring is essential for every cardiac surgical patient. Radial artery being easily accessible for cannulation under local anesthesia even without any sedation, it is preferred over femoral artery. Normal radial artery diameter ranges from 2.3 to 3.4 mm. Anatomically, radial artery has concentric smooth muscle with rich alpha 1 adrenergic innervation.[8]

Radial artery cannulation is a skilful procedure which requires expertise. However, the cannulation of radial artery still becomes difficult even by an experienced anesthesiologist in cases of feeble pulse or when he is left with only one-sided radial artery for cannulation. The most common cause of radial artery spasm being instrumentation.[9] This can lead to prolongation and/or failure to obtain access. Various studies have shown the incidence of temporary occlusion or spasm of radial artery ranging from 1.5% to 35% (mean 19%),[10] which is the most common complication.

Papaverine is a benzylisoquinoline with vasodilator property. It relaxes smooth muscle of blood vessels through multiple mechanisms. Firstly by inhibiting phosphodiesterase enzyme causing an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Secondly by causing decrease in calcium influx. Thirdly by inhibiting the release of calcium from intracellular stores.[11]

The present study demonstrated that periradial subcutaneous papaverine increased the diameter and palpability score of radial artery resulting in successful cannulation without any complications.

Osman et al. showed intra-arterial papaverine 30 mg relieved severe spasm of radial artery, unlike verapamil and nitrates which had failed to relieve spasm of radial artery during coronary angiography.[6] Review of literature[12,13] have shown 10 mg of papaverine injected intra coronary induces maximal hyperemic response in coronary vascular bed and also intra coronary papaverine 12 mg in the left coronary artery and 8 mg in the right coronary artery produced maximum vasodilatation in coronary vascular bed but with 9% drop in mean aortic blood pressure. Systemic administration of papaverine can cause hemodynamic instability. Our study showed no statistical significant difference in MAP before and after subcutaneous papaverine [Table 1] and also there was no hemodynamic instability reported in the first 2 h after injection. This can be accounted for periradial subcutaneous route of administration of papaverine.

Yavuz et al.[7] showed left internal mammary artery blood flow was increased after periarterial and intraluminal injection of papaverine as compared to topical application of papaverine. However, intraluminal injection of papaverine can lead to mechanical wall injury[14] which was not seen with periarterial route. In the present study, papaverine was administered periradial subcutaneous route.

Mussa et al.[15] observed the vasodilation properties of topically applied phenoxybenzamine, verapamil/NTG, and papaverine after incubating radial artery segments with these solutions for 15 min. They concluded that papaverine prevented vasoconstriction in response to potassium chloride and phenylephrine for 1 h. Other solution had longer duration of action. A similar study done by Harrison et al.[16] also showed papaverine had a brief period of inhibition to vasoconstrictors as compared to phenoxybenzamine after incubation of radial artery segments for 20 min in these solutions. In the present study, duration of action of papaverine was not measured. However, from the above study papaverine is shown to have a shorter duration of action which is desirable in the present study.

There has been limited literature on subcutaneous administration of vasodilators for arterial vasodilation. Candemir et al.[17] showed subcutaneous NTG increased radial artery diameter (P = 0.05) and also improvement in radial artery access time. NTG is an organic nitrate that acts principally on venous capacitance vessels and large coronary arteries.[18] In our study, periradial subcutaneous administration of papaverine which is an arterial and arteriolar vasodilator[19] showed significant vasodilation (P ≤ 0.0001) and improvement in the pulse palpability score.

Application of the study could be in cases where only single radial artery is available for cannulation such as patent ductus arteriosus, coarctation of the aorta, aortic arch aneurysm, surgeon's requirement of the radial artery as a conduit in coronary artery bypass graft.

Limitation of the study was, the duration of cannulation of radial artery was not assessed. Operator bias based on experience with the radial artery cannulation still could not be excluded.

CONCLUSION

Periradial subcutaneous administration of papaverine significantly increases radial artery diameter and pulse palpability score which facilitates the ease of cannulation of the radial artery which is required for invasive hemodynamic monitoring during perioperative management of cardiac surgical patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agostoni P, Biondi-Zoccai GG, de Benedictis ML, Rigattieri S, Turri M, Anselmi M, et al. Radial versus femoral approach for percutaneous coronary diagnostic and interventional procedures; Systematic overview and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He GW, Yang CQ. Radial artery has higher receptor-mediated contractility but similar endothelial function compared with mammary artery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1346–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouadhour A, Sideris G, Smida W, Logeart D, Stratiev V, Henry P. Usefulness of subcutaneous nitrate for radial access. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:343–6. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pancholy SB, Coppola J, Patel T. Subcutaneous administration of nitroglycerin to facilitate radial artery cannulation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:389–91. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He GW, Yang CQ. Comparative study on calcium channel antagonists in the human radial artery: Clinical implications. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(00)70222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osman F, Buller N, Steeds R. Use of intra-arterial papaverine for severe arterial spasm during radial cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20:551–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yavuz S, Celkan A, Göncü T, Türk T, Ozdemir IA. Effect of papaverine applications on blood flow of the internal mammary artery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;7:84–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Salmerón RJ, Mora R, Vélez-Gimón M, Ortiz J, Fernández C, Vidal B, et al. Radial artery spasm in transradial cardiac catheterization. Assessment of factors related to its occurrence, and of its consequences during follow-up. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58:504–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda N, Iwahara S, Harada A, Yokoyama S, Akutsu K, Takano M, et al. Vasospasms of the radial artery after the transradial approach for coronary angiography and angioplasty. Jpn Heart J. 2004;45:723–31. doi: 10.1536/jhj.45.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheer B, Perel A, Pfeiffer UJ. Clinical review: Complications and risk factors of peripheral arterial catheters used for haemodynamic monitoring in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine. Crit Care. 2002;6:199–204. doi: 10.1186/cc1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeldt FL, He GW, Buxton BF, Angus JA. Pharmacology of coronary artery bypass grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:878–88. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilsar R, Chawantanpipat C, Chan KH, Dobbins TA, Waugh R, Hennessy A, et al. Measurement of pulmonary flow reserve and pulmonary index of microcirculatory resistance for detection of pulmonary microvascular obstruction. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billinger M, Seiler C, Fleisch M, Eberli FR, Meier B, Hess OM. Do beta-adrenergic blocking agents increase coronary flow reserve? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1866–71. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dregelid E, Heldal K, Resch F, Stangeland L, Breivik K, Svendsen E. Dilation of the internal mammary artery by external and intraluminal papaverine application. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:697–703. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mussa S, Guzik TJ, Black E, Dipp MA, Channon KM, Taggart DP. Comparative efficacies and durations of action of phenoxybenzamine, verapamil/nitroglycerin solution, and papaverine as topical antispasmodics for radial artery coronary bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:1798–805. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison WE, Mellor AJ, Clark J, Singer DR. Vasodilator pre-treatment of human radial arteries; comparison of effects of phenoxybenzamine vs. papaverine on norepinephrine-induced contraction in vitro. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:2209–16. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Candemir B, Kumbasar D, Turhan S, Kilickap M, Ozdol C, Akyurek O, et al. Facilitation of radial artery cannulation by periradial subcutaneous administration of nitroglycerin. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoelting RK, Hillier SC, editors. Handbook of Pharmacology and Physiology in Anesthetic Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. Peripheral vasodilators – Nitric oxide and nitrovasodilators; pp. 359–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewin JJ, Horn ET, Winters BD. Vasoactive agents. In: Mauro M, Murphy K, Thomson K, Venbrux A, Morgan R, editors. Image – Guided Interventions. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014. pp. 97–103. [Google Scholar]