Abstract

Apocrine carcinoma of the breast is a rare, primary breast cancer characterized by the apocrine morphology, estrogen receptor-negative and androgen receptor-positive profile with a frequent overexpression of Her-2/neu protein (~30%). Apart from the Her-2/neu target, advanced and/or metastatic apocrine carcinomas have limited treatment options. In this review, we briefly describe and discuss the molecular features and new theranostic biomarkers for this rare mammary malignancy. The importance of comprehensive profiling is highlighted due to synergistic and potentially antagonistic molecular events in the individual patients.

KEY WORDS: Breast cancer, special types, apocrine carcinoma, androgen receptor, biomarkers, targeted therapy

INTRODUCTION

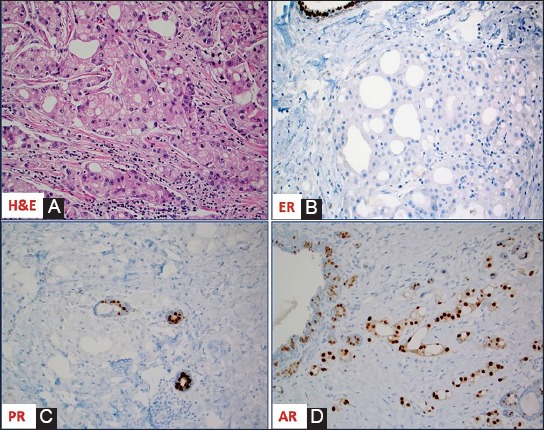

Invasive apocrine carcinoma of the breast is a rare primary breast cancer characterized by the apocrine cells with abundant eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm, centrally to eccentrically located nuclei with prominent nucleoli and distinctive cell borders [1] (Figure 1A). Mammary apocrine epithelium has a characteristic steroid receptor profile that is negative for full length estrogen receptor-alpha (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and is androgen receptor (AR) positive [2,3]. The presence of apocrine cells in more than 90% of the tumor population defines invasive apocrine carcinoma, but it is necessary to have the characteristic immunohistochemical (IHC) profile of steroid receptors (ER-/PR-/AR+) to qualify as “pure” apocrine carcinoma (PAC) [3-5] (Figures 1B-D). Such strictly defined PAC constitutes < 1% of all breast cancers [6].

FIGURE 1.

(A) Hematoxylin and Eosin slide of a case of invasive mammary carcinoma with apocrine morphology; The apocrine cells are negative for estrogen receptor [ER] (B) and progesterone receptor [PR] (C) but positive for androgen receptor [AR] (D); note the presence of ER and PR expression in adjacent normal ducts.

At the molecular level, PAC is characterized by detectable mRNA transcript of estrogen receptor, but only the alternatively spliced variant ER-36alpha (ER-36α) can be detected at the protein level (IHC) [7,8]. Progression of neoplastic disease from apocrine hyperplasia, apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) to invasive apocrine carcinoma had been proposed and investigated for genetic changes using a microdissection approach [9]. Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) revealed accumulation of chromosomal losses and gains (particularly along the chromosome 17q) as well as tumor suppressor/oncogene mutations during the phases of progression [5,9].

Activation of the AR signaling pathway is a prominent feature present in apocrine lesions of the breast including apocrine DCIS and invasive apocrine carcinoma [2]. AR upregulation is mediated through forkhead box A1 (FoxA1) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) activities [10]. Prolactin-induced protein (or GCDFP-15) is also actively regulated by the AR/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) feedback loop in apocrine cells [11,12]. Based on these data, targeting of the androgen receptor with androgen-targeting therapies, and potential combination strategies based on additional genomic alterations have been under investigation in clinical trials for triple-negative breast carcinomas, including PAC.

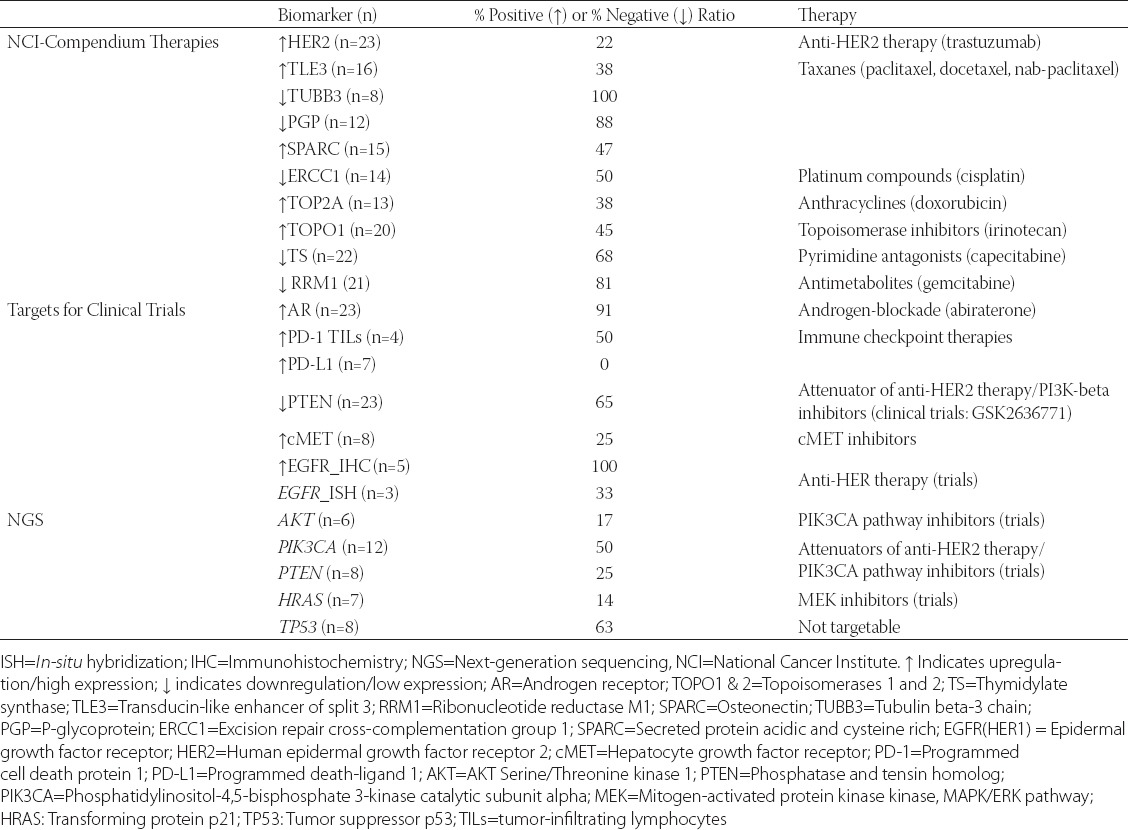

“Molecular apocrine” carcinomas exhibit prognostically poor gene signature (using validated qRT-PCR signature) with a high-risk recurrence score and a poor prognosis [13]. Comprehensive cancer profiling of PAC reveals numerous, yet individualized therapeutic options. PIK3CA/PTEN/AKT and TP53 alterations are most common in apocrine carcinoma [5,9,13,14]. Deregulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway components (KRAS, NRAS, BRAF) is less frequent [5,9] (Table 1). AR expression presents an opportunity for the treatment with androgen targeting therapies seemingly in all cases [6,15-17]. The presence of PIK3CA mutations and androgen overexpression may confer sensitivity to the combination of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AR inhibitors [18]. HER2 amplification and over-expression are seen in ~30% of tumors, while EGFR gene is amplified in a small (6%) percentage of cases despite the common epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) protein expression [3,5,6,13]. These two receptors may be targeted with monoclonal antibodies; however the high frequency of PIK3CA mutation may contribute to attenuated responses [19], and a comprehensive sample profiling (e.g. IHC for receptors and sequencing for mutations) is needed to provide optimal personalized therapy.

TABLE 1.

A summary of the biomarker profiling using a multiplatform approach (immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization and next-generation sequencing) [data from the Caris Life Science commercial laboratory, September 2016]

Biomarkers of classic chemotherapy that are variably expressed in individual cases of PAC (and the agents used to target them) include topoisomerase 2 alpha (TOPO2A) [anthracyclines], excision repair cross-complementation group 1 protein (ERCC1) [platinum drugs], ribonucleotide reductase catalytic subunit M1 (RRM1) [gemcitabine], transducin like enhancer of split 3 (TLE3) [taxanes], and thymidylate synthase (TS) [antifolates] (Table 1). Recently described immune therapies based on immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been described specifically for apocrine carcinomas, which in our limited experience do not express programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (0/8; using antibody clone SP142), in contrast to classic triple-negative breast cancers, which are more frequently PD-L1 positive (9-59%) [20,21] (Table 1).

In summary, apocrine carcinoma is a rare, distinct subtype of breast cancer with consistent AR overexpression/full length ER-α loss, frequent deregulation of the PIK3CA/phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) pathway and HER2 activation, which along with the biomarkers of conventional chemotherapy may tailor optimal treatment modalities for the patients with advanced and/or metastatic apocrine carcinoma. Targeted therapy based on immune check point inhibitors needs additional investigations as preliminary results show lack of PD-L1 expression in this cancer type.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Zoran Gatalica is an employee of Caris Life Sciences; Semir Vranic and Rebecca Feldman declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The results provided here were in part presented at the XXXI International Congress of the International Academy of Pathology and the 28th Congress of the European Society of Pathology that was held in Cologne, Germany, September 25-29, 2016 (The Breast Cancer Working Group Long Course entitled “Breast Pathology: Histology-based prognostic markers besides grade and stage (Session I) & Special types of breast cancers with clinical impact (Session II)”.

REFERENCES

- [1].Eusebi V, Millis R, Cattani M, Bussolati G, Azzopardi J. Apocrine carcinoma of the breast. A morphologic and immunocytochemical study. Am J Pathol. 1986;123(3):532–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gatalica Z. Immunohistochemical analysis of apocrine breast lesions. Pathol Res Pract. 1997;193(11-12):753–8. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(97)80053-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0344-0338(97)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vranic S, Tawfik O, Palazzo J, Bilalovic N, Eyzaguirre E, Lee LM, et al. EGFR and HER-2/neu expression in invasive apocrine carcinoma of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(5):644–53. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.50. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vranic S, Schmitt F, Sapino A, Costa JL, Reddy S, Castro M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the breast: A comprehensive review. Histol Histopathol. 2013;28(11):1393–1409. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vranic S, Marchiò C, Castellano I, Botta C, Scalzo MS, Bender RP, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular profiling of histologically defined apocrine carcinomas of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(9):1350–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mills AM, E Gottlieb C, M Wendroth S, M Brenin C, Atkins KA. Pure apocrine carcinomas represent a clinicopathologically distinct androgen receptor-positive subset of triple-negative breast cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(8):1109–16. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000671. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bratthauer GL, Lininger RA, Man YG, Tavassoli FA. Androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA status in apocrine carcinomas. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2002;11(2):113–8. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200206000-00008. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019606-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vranic S, Gatalica Z, Deng H, Frkovic-Grazio S, Lee LM, Gurjeva O, et al. ER-α36 a novel isoform of ER-α66 is commonly over-expressed in apocrine and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(1):54–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.082776. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2010.082776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Costa LJ, Justino A, Gomes M, Alvarenga CA, Gerhard R, Vranic S, et al. Comprehensive genetic characterization of apocrine lesions of the breast. Cancer Res. 2013;73(8):2013. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.AM2013-2013. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Naderi A, Meyer M, Dowhan DH. Cross-regulation between FOXA1 and ErbB2 signaling in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2012;14(4):283–96. doi: 10.1593/neo.12294. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Naderi A, Hughes-Davies L. A functionally significant cross-talk between androgen receptor and ErbB2 pathways in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10(6):542–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.08274. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.08274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Naderi A, Meyer M. Prolactin-induced protein mediates cell invasion and regulates integrin signaling in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(4):R111. doi: 10.1186/bcr3232. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lehmann-Che J, Hamy AS, Porcher R, Barritault M, Bouhidel F, Habuellelah H, et al. Molecular apocrine breast cancers are aggressive estrogen receptor negative tumors overexpressing either HER2 or GCDFP15. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(3):R37. doi: 10.1186/bcr3421. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Weisman PS, Ng CK, Brogi E, Eisenberg RE, Won HH, Piscuoglio S, et al. Genetic alterations of triple negative breast cancer by targeted next-generation sequencing and correlation with tumor morphology. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(5):476–88. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.39. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Arce-Salinas C, Riesco-Martinez MC, Hanna W, Bedard P, Warner E. Complete response of metastatic androgen receptor-positive breast cancer to bicalutamide: Case report and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(4):e21–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8899. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bonnefoi H, Grellety T, Tredan O, Saghatchian M, Dalenc F, Mailliez A, et al. A phase II trial of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with triple-negative androgen receptor positive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (UCBG 12-1) Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):812–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw067. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gucalp A, Tolaney S, Isakoff SJ, Ingle JN, Liu MC, Carey LA, et al. Phase II trial of bicalutamide in patients with androgen receptor-positive, estrogen receptor-negative metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5505–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3327. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Schafer JM, Pendleton CS, Tang L, Johnson KC, et al. PIK3CA mutations in androgen receptor-positive triple negative breast cancer confer sensitivity to the combination of PI3K and androgen receptor inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(4):406. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0406-x. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-014-0406-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shi W, Jiang T, Nuciforo P, Hatzis C, Holmes E, Harbeck N, et al. Pathway level alterations rather than mutations in single genes predict response to HER2-targeted therapies in the neo-ALTTO trial. Ann Oncol. 2016 Sep;:29. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx805. pii: mdw434. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gatalica Z, Snyder C, Maney T, Ghazalpour A, Holterman DA, Xiao N, et al. Programmed cell death (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) expression in common cancers and their correlation with molecular cancer type. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(12):2965–70. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0654. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Joneja U, Vranic S, Swensen J, Feldman R, Chen W, Kimbrough J, et al. Comprehensive profiling of metaplastic breast carcinomas reveals frequent overexpression of PD-L1. J Clin Pathol. 2016 Aug 16; doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-203874. pii: jclinpath-2016-203874. DOI: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-203874. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]