Abstract

BACKGROUND

Maternal labor force participation has increased dramatically over the last 40 years, yet surprisingly little is known about longitudinal patterns of maternal labor force participation in the years after a birth, or how these patterns vary by education.

OBJECTIVE

We document variation by maternal education in mothers’ labor force participation (timing, intensity, non-standard work, multiple job-holding) over the first nine years after the birth of a child.

METHODS

We use the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (N~3000) to predict longitudinal labor force participation in a recent longitudinal sample of mothers who gave birth in large US cities between 1998 and 2000. Families were followed until children were age 9, through 2010.

RESULTS

Labor force participation gradually increases in the years after birth for mothers with high school or less education, whereas for mothers with some college or more, participation increases between ages 1 and 3 and then remains mostly stable thereafter. Mothers with less than high school education have the highest rates of unemployment (actively seeking work), which remain high compared with all other education groups, whose unemployment declines over time. Compared with all other education groups, mothers with some college have the highest rates of labor force participation, but also high rates of part-time employment, non-standard work, and multiple job-holding.

CONTRIBUTION

Simple conceptualizations of labor force participation do not fully capture the dynamics of labor force attachment for mothers in terms of intensity, timing of entry, and type of work hours, as well as differences by maternal education.

1. Introduction

Maternal employment in the U.S. has increased dramatically over the last 40 years. Among mothers with children under 18, 47% were in the labor force in 1975 and this figure increased to more than 70% in the late 1990s, where it has remained over the last 15 years (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2009, 2014). Maternal labor force participation, employment intensity, and type of participation (non-standard work, multiple job-holding) are not only linked with economic wellbeing, but also with parenting, child care, and the home environment, all of which impact the wellbeing of families. Despite these changes in maternal labor force participation in recent decades, surprisingly few studies have investigated participation using longitudinal data. This is an important oversight as studying the continuity, intensity, and type of participation mothers engage in over time is key to understanding how and whether maternal labor force participation is linked with family wellbeing. In this descriptive report we describe maternal labor force participation (employment, unemployment, out of labor force), intensity (part- vs. full-time) and type (nonstandard, multiple job-holding), in the first nine years after giving birth.

A second aim of this paper is to describe variation in maternal labor force participation in the years after a birth by maternal education. We do this for a few reasons. Changes in U.S. social policies in the late 1990s led to a greater increase in maternal employment among the least advantaged groups (Coley et al. 2007). Research has also documented the phenomenon of “diverging destinies”, whereby the families in which children are being raised are increasingly diverging in terms of key inputs such as time, quality, and money for child health and development by maternal education (McLanahan 2004) and, more generally, there are huge disparities in economic resources that children receive by parents’ education levels (Putnam 2015). To shed light on these potential disparities, we study whether the levels, timing, and intensity of maternal labor force participation over time vary by maternal education.

A handful of studies have examined women’s labor force participation longitudinally and have found that women make numerous entries into and exits from the labor force (or employment) over the life course (Hynes and Clarkberg 2005; Moen 1985; Vandenheuvel 1997). These entries and exits have important implications for thinking about long-term earnings potential, overall economic wellbeing, and ultimately the wellbeing of families. The current study builds on these earlier studies by examining maternal labor force participation in a contemporary cohort of mothers – those who had children between 1998 and 2000, shortly after major welfare reforms in the U.S. and just after maternal labor force participation rates leveled out.

2. Data and methods

2.1 Data

We use longitudinal data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS; N~3000), a representative study of births to mothers in large US cities (with populations over 200,000) between 1998 and 2000. These data are ideal for studying recent maternal labor force participation patterns as the data were collected at the time of the birth and again when the child was aged 1 (1999–2001), 3 (2001–2003), 5 (2003–2006), and 9 years (2007–2010). Moreover, from the vantage point of the child, they represent the mother’s employment patterns during the first decade of that child’s life The FFCWS included approximately 5,000 births, drawing a random sample from 75 hospitals in 20 large US cities. The study oversampled non-marital births (at a ratio of 3 non-marital to 1 marital birth), resulting in a racially diverse, somewhat economically disadvantaged sample; however, the sample was designed so that when the data are weighted they are representative of mothers who gave birth in the late 1990s in large U.S. cities. The weights also adjust for non-response and attrition. Because we are looking at patterns over time we restrict our sample to include mothers who are in all survey waves, N=2,986 (the substantive findings are very similar when the analyses are not restricted to mothers who are in all survey waves; analyses available upon request).

The 9-year follow-up of the FFCWS occurred from 2007–2010. This is significant because the Great Recession began in the U.S. in December 2007 and ended in June 2009 (as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research). As a result, many of the mothers of the 9-year-olds surveyed were interviewed during the Great Recession, which may have affected their labor force participation. Thus, although the results reflect a contemporary birth cohort, they may not reflect typical circumstances faced by urban mothers with 9-year-old children.

2.2 Measures

Our key variable of interest is maternal labor force participation and we construct measures at each survey wave. We examine two variables, labor force participation and employment. Following the Bureau of Labor Statistics, mothers are considered to be in the labor force if they report that they are currently employed or if they are looking for work (unemployed), otherwise mothers are considered out of the labor force. Mothers are asked “Last week, did you do any regular work for pay?” and if they report working or being on vacation they are considered employed. Mothers who are not working are asked if they are looking for work, and, if they are, they are considered unemployed. To investigate the intensity of labor force participation, we separate mothers who are employed full-time (defined as working 30 hours or more per week) from those employed part-time (less than 30 hours a week).

We also study maternal non-standard work hours and multiple job-holding. We construct a measure of any non-standard work if mothers report working evenings, nights, weekends, or shifting schedules (following Dunifon et al. 2013). Multiple job-holding is coded as 1 if mothers report working more than one job at the same time.

In all our analyses we investigate differences in maternal labor force participation by mother’s education, which is coded as less than high school, high school, some college, and college or higher. Twenty-four percent of mothers in our sample have less than a high school education, 32% have a high school degree, 21% some college, and 24% a college degree or greater.

We include a number of demographic characteristics that have been linked in prior research with maternal labor force participation as control measures in our analyses. Specifically, we include race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other race/ethnicity), maternal age at the birth, whether she was foreign-born, and time-varying measures of relationship status (married, cohabiting, single) and the number of children in the household (to account for birth order and subsequent births). Table 1 documents the demographic make-up of the sample by maternal education.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by maternal education (%)

| Education | All | < High School | High School | Some College/ Assoc. | College + |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 32 | 21 | 24 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 24 | 28 | 32 | 28 | 6 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 41 | 19 | 36 | 45 | 68 |

| Hispanic | 27 | 47 | 28 | 23 | 9 |

| Other | 8 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 18 |

| Relationship status at birth | |||||

| Married | 63 | 37 | 51 | 68 | 96 |

| Cohabiting | 19 | 28 | 27 | 18 | 1 |

| Single | 18 | 35 | 22 | 14 | 2 |

| Mother’s age at birth | |||||

| <20 | 12 | 31 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| 20–24 | 24 | 35 | 30 | 30 | 2 |

| 25–29 | 27 | 20 | 33 | 28 | 24 |

| 30+ | 38 | 15 | 25 | 39 | 74 |

| Number of children at age 1 (Mean/SD) | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.53 (1.5) | 2.33 (1.2) | 2.02 (1.0) | 1.87 (1.1) |

| Foreign-born | 20 | 31 | 19 | 10 | 17 |

| N | 2986 | 926 | 944 | 767 | 349 |

Note: Statistics are weighted by national weights. The sample is restricted to mothers who were interviewed in all survey waves.

2.3 Method

Multivariate models, controlling for the demographic characteristics specified above, are run and used to predict labor force participation rates by education level at each survey wave. All analyses are weighted using national weights, which adjust for attrition and sample design (to account for the oversample of non-marital births) and to provide estimates that are representative of mothers in large US cities. Our goal is to describe variation in the patterns of mothers’ labor force participation post-birth as a function of several key characteristics associated with maternal employment. By controlling for a number of demographic factors that might be confounded with maternal education we can observe how labor force participation patterns vary by education, net of a number of key demographic characteristics, to better ensure that the variation we observe is largely driven by education as opposed to, say, the birth of a new child or race/ethnic differences in education and employment.

3. Results

3.1 Patterns of labor force participation

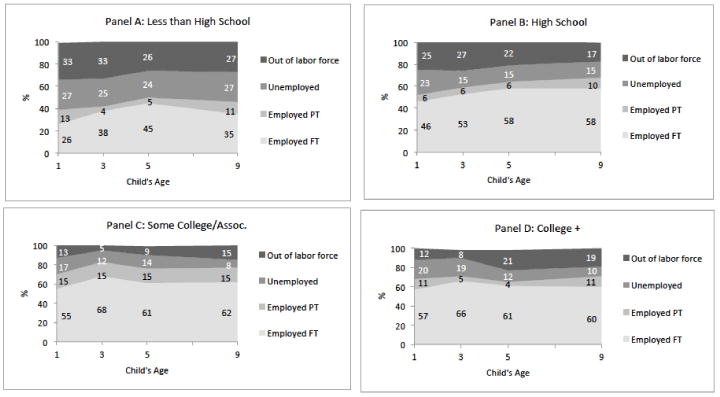

Figure 1 plots predicted labor force participation among urban mothers after the birth of a child by the child’s age and by maternal education level, controlling for maternal characteristics (race/ethnicity, age, nativity, relationship status, and number of children in the household). Looking across the four panels, we see that labor force participation rates vary greatly by maternal education. Participation rates are highest for mothers with some college education, followed by college-educated mothers, then high-school-educated mothers, and finally mothers with less than a high school degree, who have the lowest participation rates. Although on average labor force participation increases over time, the timing of the increase and even the overall trend varies by maternal education.

Figure 1. Labor force participation by child’s age and by maternal education.

Note: PT= Part-time, FT= Full-time. All figures are predicted percentages, adjusted by the number of children in the household, maternal relationship status, maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, and immigrant status. All analyses are weighted using national weights. The sample is restricted to mothers who were interviewed in all survey waves, N=2986.

Starting with mothers with less than high school (Panel A), a sharp increase in full-time employment occurs from age 1 to 3, accompanied by a sharp decline in part-time employment (and level rates of labor force participation and unemployment). Full-time employment continues to increase through age 5. At age 9, possibly as a result of the Great Recession, mothers with less than high school are more likely to be employed part-time, and less likely to be working full-time, whereas unemployment remains high and relatively level over the whole time period for this group (about 25%).

For mothers with a high school education (Panel B), the pattern is quite different. Mothers’ overall participation in the labor force increases over time, but unlike mothers with less than high school, full-time employment in this group increases from ages 1 to 3 to 5, and remains steady through age 9, but part-time employment, which remains steady from ages 1 to 5, also increases at age 9 (possibly due to the Great Recession, if more mothers would have otherwise chosen full-time employment). Unemployment declines sharply from ages 1 to 3 and then remains steady at 15% for high-school-educated mothers (11 percentage points lower than that of mothers with less than high school). Thus, over time, mothers with a high school degree are more likely to enter the labor force, and, among those in the labor force, more are employed.

Panel C documents the trends in labor force participation for mothers with some college education and Panel D shows the trends for college-educated mothers. At first glance, the patterns for mothers with some college and college education are relatively similar. Both sets of mothers experience a bump up in full-time employment from ages 1 to 3 and then a decline from ages 3 to 5 that remains level through age 9. Rates of unemployment are generally declining for both groups over time. College-educated mothers experience a large decrease in unemployment from 3 to 5; however, much of this decline occurs because college-educated mothers are moving out of the labor force (an increase of 13 percentage points), whereas far fewer mothers with some college exit the labor force (an increase of 4 percentage points). Patterns in part-time employment also vary across the two groups. Fifteen percent of mothers with some college work part-time at each year, whereas for college-educated mothers, levels of part-time work are lower and there is a decline in part-time work from ages 1 to 3 and an increase at age 9 (possibly due to the Great Recession).

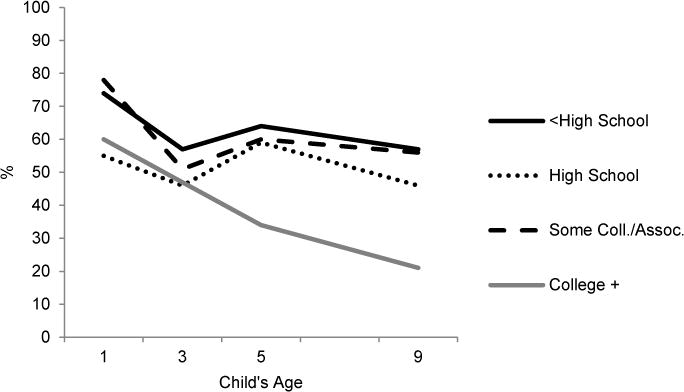

3.2 Non-standard employment and multiple-job holding

In Figure 2 we document the predicted percentage of mothers working any non-standard hours by child’s age and mother’s education among mothers who are employed. We see that over time there is a general decline in the percentage of mothers who are working non-standard work hours, but that the decline is steepest for college-educated mothers: whereas 60% of employed college-educated mothers work some non-standard hours at age 1, by age 9 only 21% do likewise. In comparison, for all other groups there is a decline from ages 1 to 3 but then a relative leveling off, and for employed mothers with some college, 56% are working non-standard work schedules at age 9, more than twice the percentage of college-educated mothers.

Figure 2. Non-standard work by child’s age and maternal education, among employed mothers.

Note: All figures are predicted percentages, adjusted by the number of children in the household, maternal relationship status, maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, and immigrant status. All analyses are weighted using national weights. The sample is restricted to mothers who were interviewed in all survey waves, N=2986.

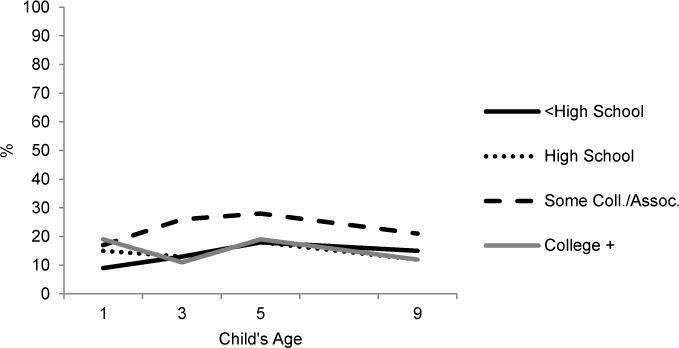

In Figure 3 we document predicted multiple-job holding among mothers who are employed. Here we see a general pattern that shows an increase in multiple-job holding over time from about age 1 to 5 and then a decline at age 9. These patterns are relatively similar across education groups, but the levels are quite different. Mothers with some college education have the highest rates of multiple-job holding, whereas college-educated mothers generally have the lowest rates.

Figure 3. Multiple-job holding by child’s age and maternal education, among employed mothers.

Note: All figures are predicted percentages, adjusted by the number of children in the household, maternal relationship status, maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, and immigrant status. All analyses are weighted using national weights. The sample is restricted to mothers who were interviewed in all survey waves, N=2986.

4. Conclusion

Using recent longitudinal data, this paper examines mothers’ labor force participation from when their child was age 1 through age 9 and is the first to study variation in the patterns of participation among mothers over time to examine whether the specific timing of their labor force entry and intensity of employment varied by maternal education. Our study builds on previous studies of maternal labor force participation to show that the timing and intensity of labor force participation varies considerably by maternal education level. Mothers with high school or less education increase their labor force participation gradually over time, moving toward full-time work as their children age. By comparison, mothers with some college education or more have a bump up in participation (and intensity) at age 3, but overall have flatter labor force participation over time.

Mothers with less than a high school degree have the weakest labor force attachment; these mothers have the lowest rates of full-time work, the highest rates of being out of the labor force, and the highest rates of unemployment, which remain high over time; whereas for all other education groups, unemployment declines as children age. We also see that at age 9, when the Great Recession hit, mothers with less than high school have a 10-percentage point decline in full-time work and a small increase in part-time work, which does not occur for mothers in the other groups (although there is an increase in part-time work for both high school and college-educated mothers, possibly due to the Great Recession). This finding is consistent with work that has shown that the recession hit less-educated populations hardest (Hoynes, Miller, and Schaller 2012), especially those individuals at the very bottom of the income distribution (Sum and Khatiwada 2010), and suggests that disparities in employment by education level persist over time.

Surprisingly, we found that mothers with some college education had the highest predicted rates of labor force participation, even higher than college-educated mothers. Additional analyses, however, indicated that mothers with some college education were more likely to work part-time, work non-standard hours, and hold multiple jobs than college-educated mothers. Thus, although overall labor force participation and employment rates may be higher than that of college-educated mothers, the quality of employment (nonstandard work, multiple job-holding) is likely lower for mothers with some college.

This study has a few limitations. First, as noted earlier, it is likely that the Great Recession affects our findings for age 9. Although our descriptive findings do not suggest higher unemployment rates in the age 9 analyses than in earlier waves, it is likely that had there been no recession the unemployment rates would have been lower and more mothers would have entered the labor force. Nonetheless, we are describing labor force participation patterns in a recent cohort of mothers – those that faced the Great Recession. Second, the findings here are limited to mothers in large US cities with young children, and are specific to a cohort of women who gave birth between 1998 and 2000. Labor force participation rates in the FFCWS study are higher than national estimates when the children are young, but converge with national estimates as the children age. Third, the periodicity of the panel means we are missing periods of employment. Finally, attrition may affect our findings. Although the weights adjust for non-response and attrition, we know that mothers who attrite are more economically disadvantaged and slightly more likely to be unemployed than those who do not leave the sample. Thus, to the extent that the weights do not fully account for attrition, our estimates may misstate employment and labor force participation levels over time.

In spite of these limitations, our study offers some important lessons. Our findings suggest that simple conceptualizations of labor force participation do not fully capture the dynamics of labor force attachment for mothers in terms of intensity, timing of entry, and type of work hours. They also suggest that disparities by maternal education in employment and labor force participation persist over time, supporting the concept of “diverging destinies”. Future research should consider whether longitudinal patterns of maternal labor force participation affect the wellbeing of families and children, and examine differences by maternal education.

References

- Bureau of Labor Statistics U.S. Department of Labor. Labor force participation rate of mothers by age of own child. Washington, DC: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2014. Mar, 1976–2012 [electronic resource] http://www.dol.gov/wb/stats/LForce_rate_mothers_child_76_12_txt.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics U.S. Department of Labor. Labor force participation rate of women by age of youngest child. Washington, DC: The Editors Desk, US Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2009. Mar, 1975–2007 [electronic resource] http://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2009/jan/wk1/art04.txt. [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Lohman BJ, Votruba-Drzal E, Pittman LD, Chase-Lansdale PL. Maternal functioning, time, and money: The world of work and welfare. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29(6):721–741. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon R, Kalil A, Crosby DA, Su JH, DeLeire T. Measuring maternal nonstandard work in survey data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(3):523–532. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoynes HW, Miller DL, Schaller J. Who suffers during recessions? National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes K, Clarkberg M. Women’s employment patterns during early parenthood: A group based trajectory analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(1):222–239. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00017.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41(4):607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. Continuities and discontinuities in women’s labor force participation. In: Elder GH Jr, editor. Life course dynamics: trajectories and transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 1985. pp. 113–155. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sum A, Khatiwada I. Labor underutilization problems of U.S. workers across household income groups at the end of the Great Recession: A truly great depression among the nation’s low income workers amidst full employment among the most affluent. Boston: Center for Labor Market Studies, Northeastern University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenheuvel A. Women’s roles after first birth. Variable or stable? Gender & Society. 1997;11(3):357–368. doi: 10.1177/089124397011003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]