Abstract

To cope with proteotoxic stress, cells attenuate protein synthesis. However, the precise mechanisms underlying this fundamental adaptation remain poorly defined. Here we report that mTORC1 acts as an immediate cellular sensor of proteotoxic stress. Surprisingly, the multifaceted stress-responsive kinase JNK constitutively associates with mTORC1 under normal growth conditions. Upon activation by proteotoxic stress, JNK phosphorylates both RAPTOR at Ser863 and mTOR at Ser567, causing partial disintegration of mTORC1 and subsequent translation inhibition. Importantly, HSF1, the central player in the proteotoxic stress response (PSR), preserves mTORC1 integrity and function by inactivating JNK, independently of its canonical transcriptional action. Thereby, HSF1 translationally augments the PSR. Beyond promoting stress resistance, this intricate HSF1-JNK-mTORC1 interplay, strikingly, regulates cell, organ and body sizes. Thus, these results illuminate a unifying mechanism that controls stress adaptation and growth.

Introduction

Proteostasis is constantly challenged by environmental stressors1. These insults cause protein misfolding and aggregation, perturbing proteostasis and inflicting proteotoxic stress2. Accordingly, cells have evolved a defensive mechanism—the heat-shock, or proteotoxic stress, response (PSR)3.

Proteotoxic stressors induce expression of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) in cells, the hallmark of the PSR. HSPs are molecular chaperones that facilitate folding, transportation, and degradation of other proteins4, thereby guarding the proteome against misfolding and aggregation. Through preservation of proteostasis, the PSR is essential for cells and organisms to survive deleterious environments. In mammals, heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) is the master regulator of the PSR3. By mounting a protective transcriptional program, HSF1 enhances cardiomyocyte survival of ischemia/reperfusion injury, antagonizes neurodegeneration, and prolongs lifespan5. Surprisingly, emerging studies reveal that HSF1 promotes oncogenesis6,7,8,9,10,11,12.

Beyond HSP induction, proteotoxic stressors provoke a systemic cellular response. Particularly, proteotoxic stress attenuates protein translation13. A prominent regulator of translation is mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), which forms two protein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 senses environmental cues and governs translation via phosphorylating EIF4EBP1 (4EBP1) and p70S6K (S6K)14. Metabolic, hypoxic, and nutritional stress inhibit mTORC1 through diverse mechanisms15,16,17,18. By contrast, little is known of how proteotoxic stress regulates mTORC1.

Herein we report that c-JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) associates with mTORC1, poised to sense proteotoxic stress. While JNK activation by proteotoxic stress disintegrate mTORC1 to suppress translation, HSF1 preserves mTORC1 activity and translation through inactivation and sequestration of JNK, thereby promoting stress resistance and growth

Results

Proteotoxic stress activates JNK and suppresses mTORC1

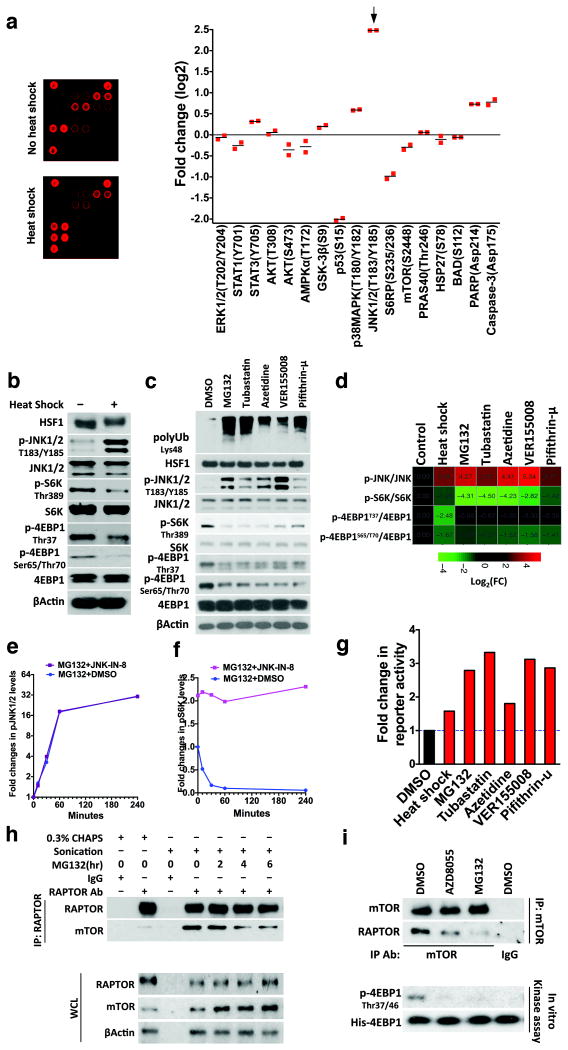

To pinpoint the signals triggered by proteotoxic stress to inhibit translation, we profiled signaling alterations following heat shock (HS), a classic proteotoxic stressor. The most responsive pathway is JNK signaling (Fig. 1a), indicated by elevated Thr183/Tyr185 phosphorylation, modifications critical to JNK activation19. By contrast, HS diminished S6K and 4EBP1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Proteotoxic stress activates JNK signaling but suppresses mTORC1 activity.

(a) Profiling HS-induced alterations in major signal transduction pathways. Following HS at 45°C for 30 min, lysates of HEK293T cells were incubated with phospho-antibody arrays (left). Results are presented as fold changes (mean of 2 technical replicates from one experiment). (b)-(d) HEK293T cells were heat shocked at 45°C for 30 min (b) or treated with other stressors (500 nM MG132, 10 μM tubastatin, 5 mM azetidine, 40 μM VER155008, or 20 μM Pifithrin-μ) for 6 hr (c). DMSO was a solvent control. Fold changes in protein phosphorylation were presented as a heat map (d). (e) and (f) HEK293T cells were treated with 500 nM MG132 for indicated times, with or without pre-treatment with 3 μM JNK-IN-8 for 60 min (mean of 3 wells of cells per time point per experiment, and this experiment was repeated twice). p-JNK and p-S6K proteins were quantitated by sandwich ELISA (Cell Signaling Technology). (g) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with AP1-secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) and CMV-Gaussia luciferase (GLuc) reporter plasmids. After 24 hr cells were treated with stressors as described in (b) and (c). Reporter activities were measured 24 hr later and SEAP activities were normalized against GLuc activities (mean of 5 wells of cells per group per experiment, and this experiment was repeated twice). (h) HEK293T cells were treated with 500 nM MG132 for indicated time and endogenous RAPTOR-mTOR interactions were examined by coIP. WCL: whole cell lysate. (i) After treatment with 500 nM MG132 or 1 μM AZD8055 for 4 hr, mTOR complexes were precipitated from HEK293T cells. mTORC1 kinase activities were measured in vitro using recombinant human His-EIF4EBP1 proteins as the substrate. Phosphorylation of 4EBP1 was detected by immunoblotting. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Source data for Fig. 1a, e, f, g can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

We further examined various proteotoxic stressors, including proteasome inhibitor MG132, histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) inhibitor tubastatin, amino acid analog azetidine, and HSC70/HSP70 inhibitors (VER155008 and Pifithrin-μ)3,20,21,22. Despite their diverse mechanisms of action (Supplementary Fig. 1a), these stressors all induced protein Lys48 ubiquitination (Fig. 1c), a modification marking proteins for proteasomal degradation23. This increased ubiquitination signified perturbation of proteostasis. These stressors all triggered JNK phosphorylation and diminished phosphorylation of mTORC1 effectors (Fig. 1b-d), which were not due to impaired cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Furthermore, these two opposing events occurred simultaneously following MG132 treatment even for 10 minutes; importantly, JNK-IN-8, the first irreversible JNK inhibitor 24, both elevated the basal S6K phosphorylation and completely rescued the MG132-induced suppression (Fig. 1e, f). Elevated JNK phosphorylation indicated activation, evidenced by mobilization of activator protein 1 (AP1) (Fig. 1g), a JNK-regulated transcription factor complex25. These results suggest a causal role of JNK activation in suppressing mTORC1 signaling. Proteotoxic stressors also induced p38 MAPK Thr180/Tyr182 phosphorylation (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Both p38 and JNK belong to the MAPK family and respond to stress stimuli26. In contrast to JNK-IN-8, SB202190, a specific p38 MAPK inhibitor27, did not affect MG132-induced mTORC1 suppression (Supplementary Fig. 1d), indicating a non-causal role of p38. Blockade of MG132-induced p38 phosphorylation by SB202190 indicates p38 inactivation27 (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

To assess mTORC1 integrity, we examined RAPTOR-mTOR associations28, by co-immunoprecipitation (coIP). We compared two cell lysis conditions, 0.3% CHAPS buffer versus sonication without detergents28,29. Since sonication enabled more efficient coIP (Fig. 1h), we employed this condition. In HEK293T cells, 4-hour MG132 treatment disrupted RAPTOR-mTOR associations (Fig. 1h), further supported by in vitro mTORC1 kinase assays. The ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitor AZD8055 and 4-hour MG132 treatment both markedly impaired in vitro phosphorylation of recombinant 4EBP1 by immunoprecipitated mTORC1 (Fig. 1i). These results indicate that proteotoxic stressors commonly provoke two concurrent events: JNK activation and mTORC1 inhibition.

JNK negatively regulates mTORC1, protein translation, and cell size

To confirm JNK-mediated mTORC1 inhibition, we genetically blocked JNK signaling. Mammals express two ubiquitous JNK isoforms, JNK1 and 225. JNK1/2 knockdown prevented MG132-induced RAPTOR-mTOR dissociations and mTORC1 suppression (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Transient JNK-IN-8 treatment exerted similar effects (Supplementary Fig. 2b), demonstrating a causative role of JNK in mTORC1 inhibition genetically and pharmacologically.

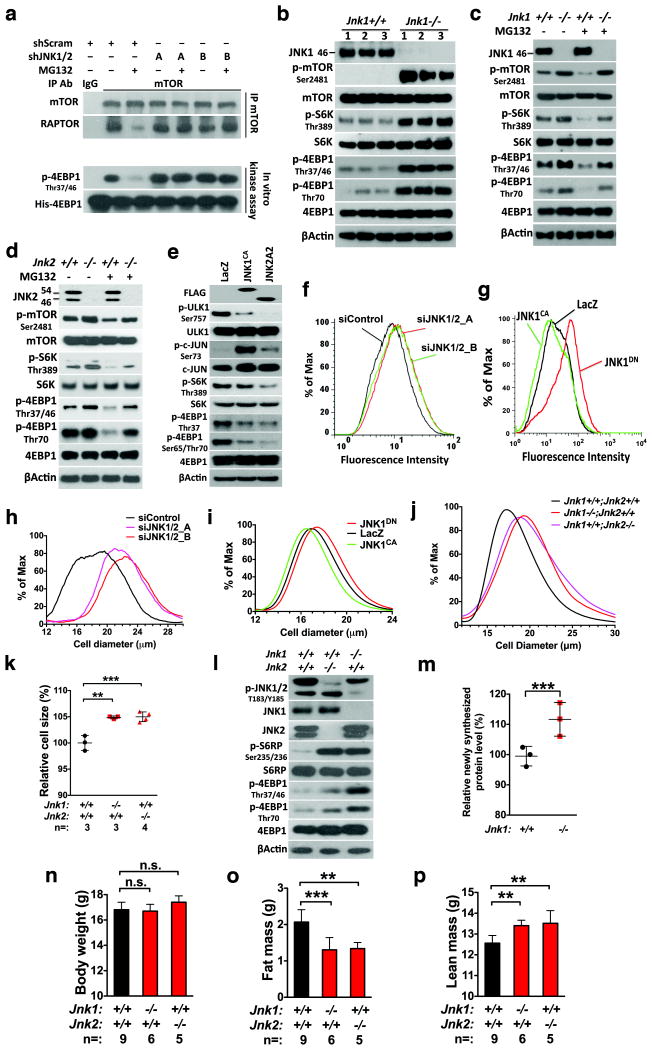

Figure 2. JNK negatively regulates mTORC1, translation, and cell size.

(a) HEK293T cells were stably transduced with lentiviral scramble or two combinations of JNK1/2-targeting shRNAs, A (shJNK1_2 and shJNK2_1) and B (shJNK1_4 and shJNK2_2). Transduced cells were treated with DMSO or 500 nM MG132 for 4 hr. (b) Three independent lines of primary MEFs were prepared for each genotype. (c) and (d) Primary Jnk1-/- or Jnk2-/- MEFs were treated with 200 nM MG132 for 6 hr. While JNK1 antibodies only recognized the p46 isoform, JNK2 antibodies recognized both p54 and p46 isoforms. (e) HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids for 48 hr. The JNK1CA plasmid encodes a fusion protein between MKK7 and JNK1A1. (f) and (g) Following transfection with indicated siRNAs or plasmids, HEK293T cells were labeled with 6-FAM-dc-puromycin for 30 min and analyzed by flow cytometry. (h)-(j) Sizes of transfected HeLa cells (h and i) and primary Jnk-deficient MEFs (j) were measured by a Multisizer™ 3 Coulter Counter. JNK manipulation causes statistically significant changes in cell size distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p<0.001). (k) Freshly prepared single liver cell suspensions were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results were normalized against wild-type controls (mean±SD, n=3 or 4 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (l) mTORC1 signaling in livers of 6-week-old male mice was immunoblotted. (m) Two hours before harvesting tissues, mice were i.p. injected with 1mg puromycin. The levels of puromycin-labeled proteins in livers were quantitated by ELISA (mean±SD, n=3 mice per genotype, unpaired two-tailed Student's t test). (n)-(p) Whole-body weight and composition were measured in 6-week-old female mice (mean±SD, n=5, 6, or 9 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). Statistics source data for 2k, m can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

To delineate how individual JNK isoforms regulate mTORC1, we utilized Jnk-deficient mice. Jnk1-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) displayed elevated basal 4EBP1 and S6K phosphorylation and mTOR Ser2481 autophosphorylation30 (Fig. 2b), indicating mTORC1 activation. Furthermore, MG132 stimulated JNK phosphorylation but reduced S6K, 4EBP1, and mTOR phosphorylation in Jnk1+/+ MEFs, which were mitigated in Jnk1-/- cells (Fig. 2c). Similar results were obtained in Jnk2-/- MEFs (Fig. 2d), indicating that both JNK1 and JNK2 are necessary for mTORC1 inhibition. MG132 did not evidently impair cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d).

To address whether JNK activation suffices to inhibit mTORC1, we expressed either a constitutively active JNK1CA or a wild-type JNK2A231,32. Results indicate the sufficiency; JNK activation, indicated by elevated c-JUN phosphorylation, impaired S6K, 4EBP1, and ULK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 2e). mTORC1 phosphorylates ULK1 at Ser757 to suppress autophagy33. Interestingly, JNK1CA impaired 4EBP1 and ULK1, but not S6K, phosphorylation (Fig. 2e). Given that JNK1CA is a fusion protein between JNK1 and its kinase MKK734, we reasoned that MKK7 might phosphorylate S6K independently of mTORC1, counteracting the JNK1 effect. Indeed, MKK7 knockdown impaired S6K phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 2e). In contrast to JNK1CA, JNK2A2 without MKK7 fusion suppressed S6K phosphorylation; and JNK-IN-8 further increased S6K phosphorylation in JNK1CA-expressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 2f), excluding potential JNK-mediated phosphorylation. Moreover, either JNK1CA or JNK2A2 sufficed to disrupt RAPTOR-mTOR associations (Supplementary Fig. 2g). These results confirm JNK1/2 as an mTORC1 suppressor and reveal an unexpected MKK7-dependent S6K phosphorylation.

We next asked whether JNK impacts mTORC1-mediated translation14. To measure translation rate, we employed a labeling technique that exploits the property of puromycin to covalently attach to nascent polypeptides35. As expected, AZD8055 reduced puromycin labeling (Supplementary Fig. 2h), indicating impaired translation. Conversely, JNK knockdown enhanced puromycin labeling (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2i). JNK1CA and JNK1DN reduced and enhanced, respectively, puromycin labeling (Fig. 2g)19, indicating translation suppression by JNK.

We asked whether JNK impacts the mTORC1-mediated cell-size control36. JNK knockdown enlarged cell size; furthermore, JNK1CA and JNK1DN reduced and increased, respectively, cell size (Fig. 2h, i). JNK1CA failed to further reduce cell size following AZD8055 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2j), suggesting that JNK acts largely via mTORC1. The negative cell-size control by JNK was confirmed in primary MEFs and mouse liver cells (Fig. 2j, k). Congruently, Jnk-/- mouse livers displayed elevated mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 2l). Phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein (S6RP) was used to indicate S6K activation37, due to weak S6K phosphorylation signals in tissues. Importantly, Jnk1-deficient livers exhibited heightened translation (Fig. 2m). mTORC1 signaling was also elevated in Jnk-deficient skin and kidneys (Supplementary Fig. 2k, l). We then investigated whether JNK impacts body size. Paradoxically, wild-type and Jnk-deficient mice exhibited similar body weights (Fig. 2n and Supplementary Fig. 2m). Given reduced fat tissues in Jnk1-/- mice38, we reasoned that this might obscure mTORC1-mediated body weight increase. Revealed by body composition analyses, Jnk-deficient mice had an average 0.7g less fat mass; by contrast, they gained an average 0.9g lean mass (Fig. 2o, p and Supplementary Fig. 2n, o). Collectively, these results indicate that JNK negatively regulates cell size and body lean mass via mTORC1 but positively regulates fat mass, likely independently of mTORC1.

JNK physically phosphorylates mTORC1

We investigated whether mTORC1 is a substrate for JNK. Several mTORC1 components, including mTOR, RAPTOR, GβL/mLST8, and PRAS40, were co-precipitated with JNK even under basal conditions (Fig. 3a). MG132 markedly diminished coIP of mTOR and GβL/mLST8 with JNK; by contrast, coIP of RAPTOR and PRAS40 with JNK remained unaltered (Fig. 3a), revealing their constitutive interactions. Interestingly, we did not detect interactions of JNK with RICTOR (Fig. 3b), a unique mTORC2 component14. These results indicate that JNK specifically associates with mTORC1 under non-stress conditions, and that proteotoxic stress selectively dissociates mTOR and GβL/mLST8 from this complex.

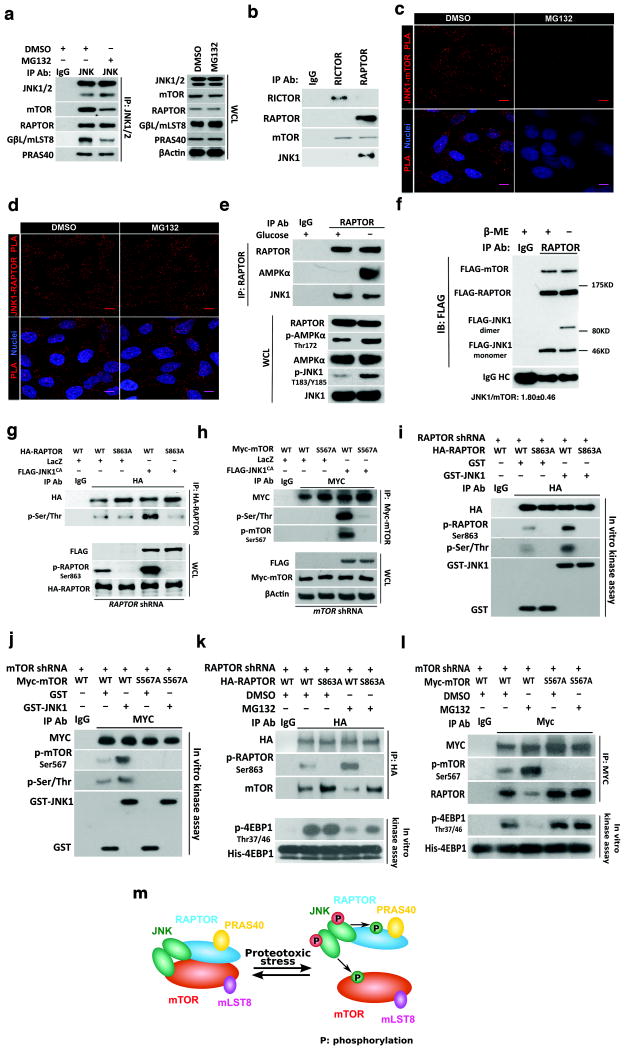

Figure 3. JNK physically associates with mTORC1.

(a) Following IP of endogenous JNK1/2 from HEK293T cells treated with and without 500 nM MG132 for 4 hr, mTORC1 components were immunoblotted. (b) Following IP of endogenous RICTOR and RAPTOR from HEK293T cells, mTOR and JNK1 proteins were immunoblotted. (c) and (d) Endogenous JNK1-mTOR and JNK1-RAPTOR interactions were detected by PLA in HeLa cells with and without 500 nM MG132 treatment for 4 hr. Mouse anti-JNK1 (JM2671) and rabbit anti-mTOR (7C10) were used for JNK1-mTOR PLA. Rabbit anti-JNK1/3 (C-17) and mouse anti-RAPTOR (1H6.2) were used for JNK1-RAPTOR PLA. Scale bars: 10 μm. Images are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (e) HEK293T cells were deprived of glucose for 4 hr. Following IP of endogenous RAPTOR, AMPKα and JNK1 were immunoblotted. (f) Following co-transfection of FLAG-mTOR, FLAG-RAPTOR, and FLAG-JNK1 plasmids into HEK293T cells, RAPTOR was precipitated using anti-RAPTOR antibodies and co-precipitated mTOR and JNK1 were immunoblotted under both no-reducing and reducing conditions using anti-FLAG antibodies. FLAG signals were quantitated by ImageJ software (mean±SD, n=3 independent experiments). β-ME: 2-mercaptoethanol. HC: heavy chain. (g) HEK293T cells stably expressing RAPTOR-targeting shRNAs were co-transfected with indicated plasmids. Following IP of HA-tagged RAPTOR, total phosphorylation of RAPTOR was immunoblotted using anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibodies. RAPTOR Ser863 phosphorylation was directly immunoblotted using phospho-specific antibodies. (h) HEK293T cells stably expressing mTOR-targeting shRNAs were co-transfected with indicated plasmids. Following IP of Myc-tagged mTOR, total and Ser567-specific phosphorylation of mTOR were immunoblotted using anti-phosphoserine/threonine and anti-phosphoSer567 antibodies, respectively. (i) and (j) Exogenously expressed RAPTOR or mTOR was precipitated from HEK293T cells, and further incubated with 100 ng recombinant GST or GST-JNK1 proteins in vitro. Total and serine-specific phosphorylation of precipitated RAPTOR and mTOR were immunoblotted. (k) and (l) HEK293T cells depleted of endogenous RAPTOR or mTOR due to stable shRNA expression were transfected with indicated plasmids and treated with DMSO or 500 nM MG132 for 4 hr. Following IP of exogenously expressed RAPTOR or mTOR, serine-specific phosphorylation and RAPTOR-mTOR interactions were immunoblotted. Activities of precipitated mTORC1 were measured in vitro using recombinant His-EIF4EBP1 proteins. (m) Schematic depiction of proposed JNK-mTORC1 interactions.

To illuminate the detailed interactions among JNK, RAPTOR, and mTOR, we employed the Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) technique, which generates signals marking close vicinity of two proteins39. Antibody specificities were verified by immunostaining (Supplementary Fig. 3a-c). Under basal conditions, endogenous JNK1-RAPTOR and JNK1-mTOR interactions were readily detectable in HeLa cells; congruent with our IP results, MG132 diminished JNK1-mTOR, but not JNK1-RAPTOR, signals (Fig. 3c, d). PLA revealed both cytoplasmic and nuclear JNK-mTORC1 interactions (Fig. 3c, d), consistent with mTORC1 distribution in both compartments40.

JNK-mTORC1 interactions differ from the well-recognized interactions between AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mTORC1. Whereas glucose deprivation activated AMPK and induced AMPK-RAPTOR associations16, JNK-RAPTOR interactions did not increase, despite JNK activation (Fig. 3e). Thus, JNK-RAPTOR associations remain constant under both MG132 treatment and glucose deprivation. Next, we determined the stoichiometry of JNK-mTORC1 complexes. Through co-expression of FLAG-tagged RAPTOR, mTOR, and JNK1, we precipitated RAPTOR and calculated the molecular ratio of co-precipitated JNK1 and mTOR as 1.8 to 1.0 (Fig. 3f). Similar results were observed for endogenous proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3d), suggesting that some mTORC1 contain two JNK molecules. Congruently, under non-reducing conditions we detected JNK1 dimers co-precipitated with RAPTOR and mTOR (Fig. 3f).

Conforming to the consensus motif Ser/Thr-Pro (Supplementary Fig. 3e)41, two strong candidate JNK phosphorylation sites, RAPTOR Ser863 and mTOR Ser567, were predicted. We then generated phosphorylation-resistant mutants, RAPTORS863A and mTORS567A. In HEK293T cells, JNK1CA expression increased both total and Ser863-specific phosphorylation of RAPTORWT, but not phosphorylation of RAPTORS863A (Fig. 3g). Similar results were observed for mTORWT and mTORS567A (Fig. 3h), suggesting these sites as major JNK phosphorylation targets. Furthermore, in vitro purified recombinant JNK1 kinases readily phosphorylated immunoprecipitated RAPTORWT and mTORWT proteins, but not their mutant counterparts (Fig. 3i, j). Importantly, incubation of JNK-IN-8, but not AZD8055, with immunoprecipitated mTORC1 and recombinant JNK1 diminished RAPTOR Ser863 and mTOR Ser567 phosphorylation but enhanced mTOR Ser2481 autophosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 3f). These results confirm JNK as the kinase directly phosphorylating RAPTOR and mTOR.

Through JNK activation, MG132 induced RAPTOR Ser863 and mTOR Ser567 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 3g, h). Substitution of endogenous RAPTOR or mTOR with phosphorylation-resistant mutants markedly antagonized MG132-induced dissociations and inhibition of mTORC1 (Fig. 3k, l and Supplementary Fig. 3i, j). Together, these results indicate that JNK physically associates with mTORC1, and strongly suggest that upon activation JNK disintegrates mTORC1 at least partially by phosphorylating RAPTOR and mTOR (Fig. 3m).

HSF1 suppresses JNK to maintain mTORC1 integrity and activity

HSF1 is pivotal to proteotoxic stress suppression and proteostasis. Previously, we uncovered defective mTORC1 signaling in Hsf1-deficient cells7, despite the elusive underlying mechanisms. Now, we asked whether HSF1 regulates mTORC1 via JNK.

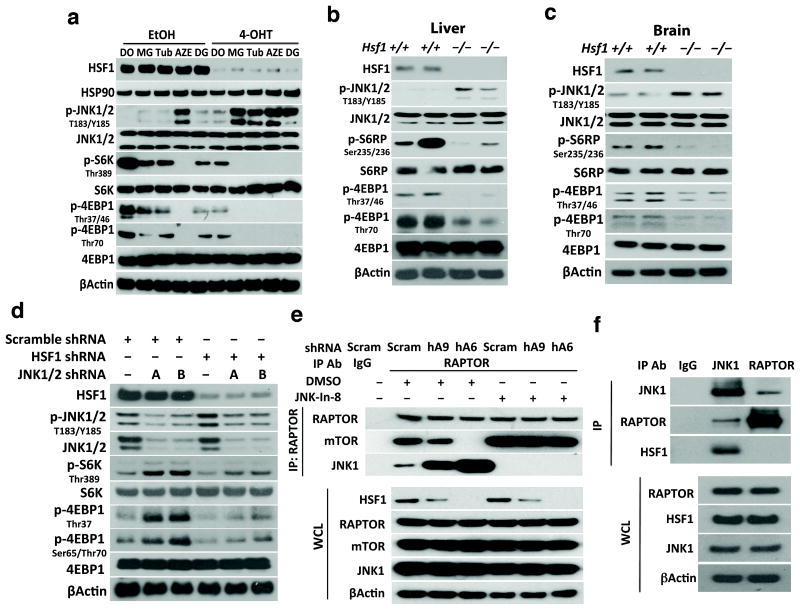

Proteotoxic stressors triggered JNK phosphorylation in immortalized MEFs carrying conditional Hsf1fl/fl alleles (Supplementary Fig. 4a and Fig. 4a). Acute Hsf1 deletion via Cre recombinase enhanced both basal and stressor-induced JNK phosphorylation, causing more severe reductions in 4EBP1 and S6K phosphorylation (Fig. 4a). These changes were not due to impaired cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Hsf1-/- livers and brains also exhibited elevated JNK phosphorylation and impaired mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 4b, c). HSF1-targeting shRNAs caused similar effects in HEK293T cells; importantly, concurrent JNK knockdown alleviated mTORC1 suppression (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, HSF1 depletion heightened JNK1-RAPTOR interactions but disrupted RAPTOR-mTOR interactions, which were rescued by JNK-IN-8 (Fig. 4e). While in HEK293T cells JNK1 precipitated both RAPTOR and HSF1, RAPTOR precipitated JNK1 but not HSF1 (Fig. 4f), indicating that HSF1 is not associated with mTORC1. PLA also detected endogenous HSF1-JNK1 interactions, predominantly nuclear, in immortalized MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d), suggesting that HSF1 sequesters JNK apart from mTORC1.

Figure 4. HSF1 maintains mTORC1 activity and integrity through inactivation and sequestration of JNK.

(a) Immortalized Rosa26-CreERT2; Hsf1fl/fl MEFs were incubated with 1 μM 4-OHT for 3 days to deplete Hsf1. Following treatments with DMSO (DO), 200 nM MG132 (MG), 10 μM tubastatin (Tub), 2.5 mM azetidine (AZE), or 200 nM 17-DMAG (DG) for 8 hr, JNK and mTORC1 signaling were immunoblotted. EtOH: ethanol; 4-OHT: 4-hydroxytamoxifen. (b) and (c) JNK and mTORC1 signaling were detected in Hsf1+/+ and Hsf1-/- mouse livers and brains, 2 mice per genotype. (d) HEK293T cells stably expressing JNK1/2-targeting shRNAs were further transfected with either scramble or HSF1-targeting shRNAs. JNK and mTORC1 signaling were immunoblotted. (e) Following treatment with 3μM JNK-IN-8 for 60 min, endogenous JNK1-RAPTOR-mTOR interactions were detected by coIP in HEK293T cells transfected with either scramble or two independent HSF1-targeting shRNAs (hA9 and hA6). (f) Following IP of endogenous JNK1 or RAPTOR proteins from HEK293T cells, co-precipitated RAPTOR, JNK1, or HSF1 proteins were immunoblotted.

Given that HSF1 regulates HSP90α expression and HSP90 chaperones mTORC142, it remains unclear whether HSP90 is implicated in mTORC1 regulation by HSF1. Transient HSF1 depletion did not reduce HSP90 proteins in both MEFs and HEK293T cells (Fig. 4a, 5a). Next, we treated HEK293T cells and MEFs with 17-DMAG, a potent HSP90 inhibitor43. In HEK293T cells, 17-DMAG suppressed mTORC1 signaling but inactivated JNK, strongly suggesting a JNK-independent mechanism; moreover, JNK-IN-8 markedly reversed mTORC1 suppression (Fig. 5a), indicating that JNK and HSP90 regulate mTORC1 via distinct mechanisms in HEK293T cells. Surprisingly, 17-DMAG activated JNK in MEFs and JNK-IN-8 fully blocked mTORC1 suppression by 17-DMAG (Fig. 5b), suggesting that in MEFs HSP90 regulates mTORC1 predominantly through JNK. These results highlight that HSF1 suppresses JNK to maintain mTORC1 activity, independently of HSP90.

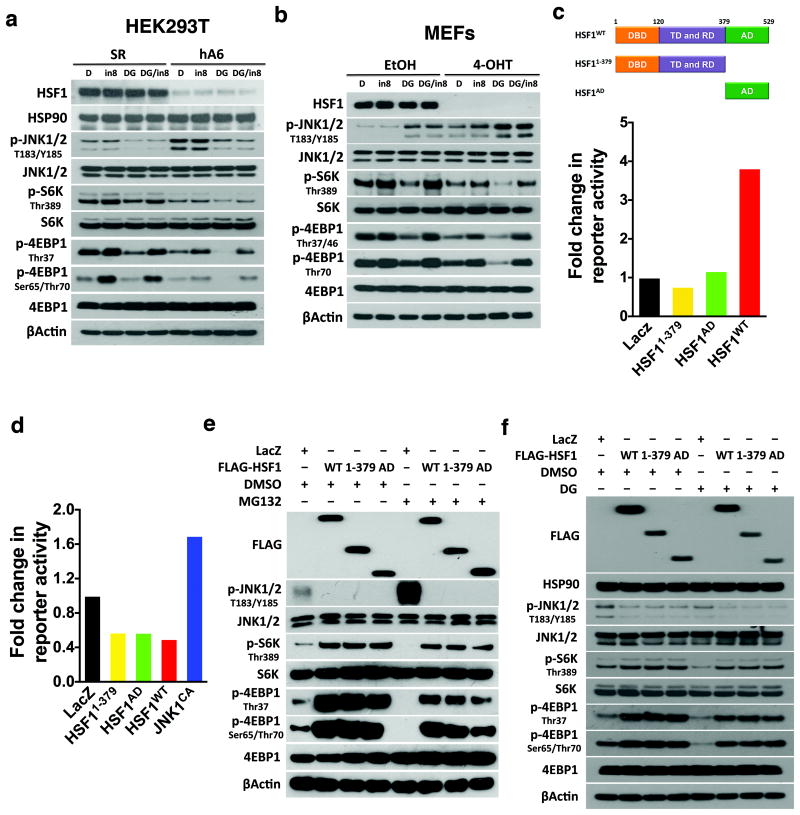

Figure 5. HSF1 suppresses JNK and activates mTORC1, independently of its transcriptional action.

(a) HEK293T cells were transfected with either scramble or HSF1-targetting (hA6) shRNAs for 4 days. Prior to immunoblotting, these transfected HEK293T cells were treated with either DMSO (DO) for 12 hr, 3 μM JNK-IN-8 (JIN8) for 60 min, 200 nM 17-DMAG (DG) for 12 hr, or combined JNK-IN-8 (JIN8) and 17-DMAG (DG) for 12 hr. (b) Immortalized Rosa26-CreERT2; Hsf1fl/fl MEFs were incubated with 1 μM 4-OHT for 3 days to deplete Hsf1. These MEFs were treated with various inhibitors as described in (a). (c) Transcriptional activities of HSF1WT, HSF11-379, and HSF1AD were measured in HEK293T cells co-transfected with heat shock element (HSE)-SEAP and CMV-GLuc reporter plasmids (mean of6 wells of cells per group per experiment, and this experiment was repeated twice). (d) JNK activities were measured in HEK293T cells using the dual AP1-SEAP and CMV-GLuc reporter system following transfection with HSF1WT, HSF11-379, and HSF1AD plasmids (meanof 6 wells of cells per group per experiment, and this experiment was repeated twice). JNK1CA served as a positive control. (e) HEK293T cells were transfected with LacZ, FLAG-HSF1WT, FLAG-HSF11-379, or FLAG-HSF1AD plasmid and treated with and without 500 nM MG132 for 4 hr. JNK and mTORC1 signaling were immunoblotted. (f) HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids were treated with and without 200 nM 17-DMAG for 12 hr prior to immunoblotting. Statistics source data for 5c, d can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

To determine whether transcriptional activity of HSF1 is required for JNK suppression, we generated two mutants, HSF11-379 lacking the transactivation domain (AD) and HSF1AD lacking the DNA-binding domain (DBD). HSF1WT, but not these two mutants, activated an HSF1 reporter (Fig. 5c). Like HSF1WT, both mutants suppressed JNK activation and rescued MG132-induced mTORC1 suppression (Fig. 5d, e), strongly suggesting transcription independence. Both wild-type and mutant HSF1 did not evidently increase HSP90, but suppressed JNK and stimulated mTORC1 in the presence of 17-DMAG (Fig. 5f), confirming HSP90 independence. Interestingly, HSF1WT, HSF11-379, and HSF1AD all co-precipitated with endogenous JNK1; moreover, their overexpression diminished endogenous JNK1-RAPTOR interactions (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Collectively, these data support a model wherein HSF1 maintains mTORC1 integrity and activity by suppressing JNK (Supplementary Fig. 4f).

mTORC1 translationally augments the PSR

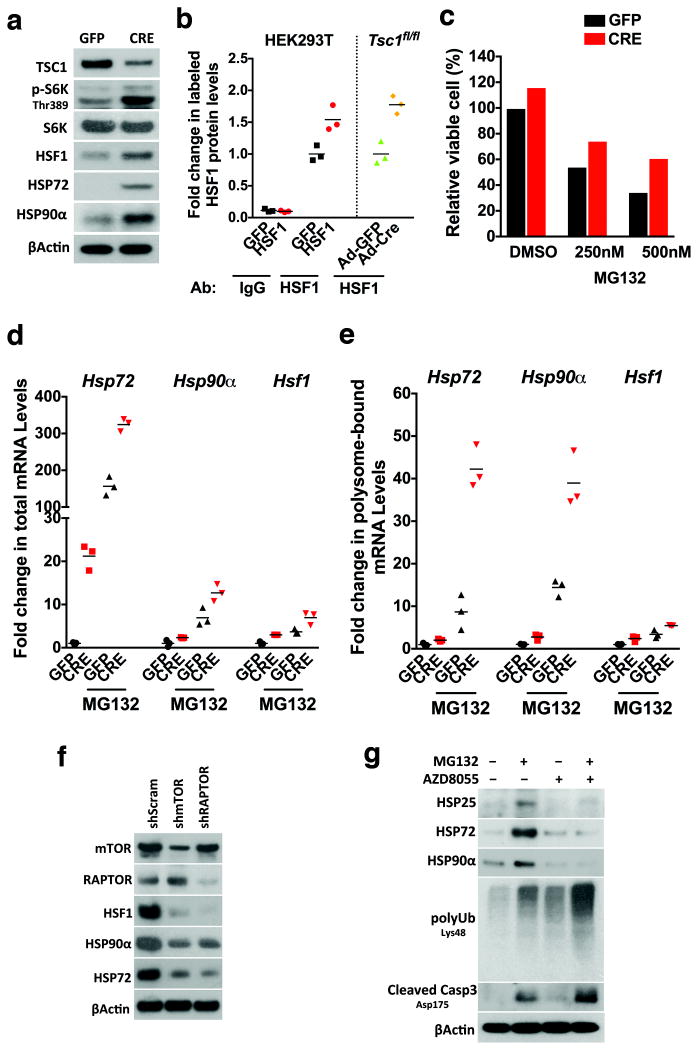

To address whether the HSF1-sustained mTORC1 activity is beneficial under proteotoxic stress, we stimulated mTORC1 by inactivating tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1), a tumour suppressor negatively regulating mTORC144. Deletion of Tsc1 in MEFs by adenoviral Cre transduction elevated S6K phosphorylation, and increased HSF1 and HSPs (Fig. 6a). More HSF1 proteins were labeled with puromycin in Tsc1-deficient cells, indicating heightened HSF1 translation (Fig. 6b). Accordingly, Tsc1-deficient cells were more resistant to MG132 treatment (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6. mTORC1 translationally augments the PSR and promotes resistance to proteotoxic stress.

(a) Primary Tsc1fl/fl MEFs were transduced with adenoviral GFP or Cre particles. Protein levels of HSF1 and HSPs were detected by immunoblotting. (b) Following transduction with adenoviral GFP or Cre particles, primary Tsc1fl/fl MEFs were labeled with 100 nM biotin-dc-puromycin for 3 hr, and lysates were incubated in ELISA plates coated with either normal IgG or anti-HSF1 antibodies (mean of3 wells of cells per group per experiment, and this experiment was repeated twice). HEK293T cells transfected with HSF1 served as a positive control. (c) Following transduction with adenoviral GFP or Cre particles, primary Tsc1fl/fl MEFs were treated with and without MG132 overnight. Viable cells were quantitated using CellTiter-Blue® reagents (mean of6 wells of cells per group per experiment, and this experiment was repeated twice). (d) and (e) Three days after transduction with adenoviral GFP or Cre particles, primary Tsc1fl/fl MEFs were treated with and without 200 nM MG132 for 4 hr. Total and polysome-associated RNAs were extracted, and mRNA levels of Hsf1 and Hsps were quantitated by qRT-PCR (mean of 3 dishes of cells per group per experiment, and these experiments were repeated three times). βActin served as the internal control. (f) HSF1 and HSP levels were detected by immunoblotting in HEK293T cells stably expressing RAPTOR- or mTOR-targeting shRNAs. (g) Hsf1+/+ MEFs were treated with 200 nM MG132 and/or 1 μM AZD8055 overnight. HSP, Lys48-specific ubiquitination, and cleaved caspase 3 were immunoblotted. Source data for Fig. 6b, c, d, e, can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Although total mRNA levels of Hsf1, Hsp72, and Hsp90α under MG132 treatment were higher in Tsc1-deficient cells, polysomal association of these mRNAs was more prominently enhanced by Tsc1 depletion (Fig. 6d, e), supporting that higher mTORC1 activity more efficiently translates these transcripts under proteotoxic stress. Conversely, either mTOR or RAPTOR knockdown diminished HSF1 and HSPs (Fig. 6f). Similarly, pharmacological mTORC1 inhibition suppressed HSF1 translation (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, AZD8055 blocked MG132-induced HSP expression, causing more severe protein ubiquitination and apoptosis (Fig. 6g). These results indicate that mTORC1 translationally amplifies the PSR to promote stress resistance.

HSF1 regulates cell, organ, and body size through JNK suppression

Congruent with its regulation of mTORC1, HSF1 overexpression enlarged HEK293T cells, which was markedly reversed by JNK1CA (Fig. 7a). Conversely, HSF1 knockdown reduced translation and cell size; and, concurrent JNK knockdown largely rescued these defects (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b and Fig. 7b).

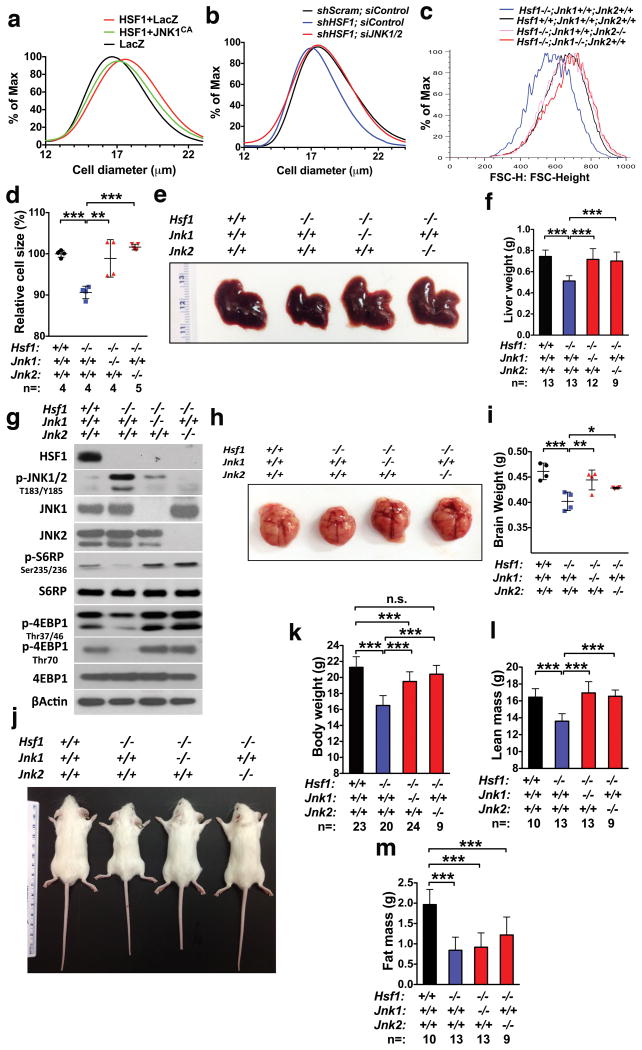

Figure 7. HSF1 positively regulates cell, organ, and body sizes through suppression of JNK.

(a) and (b) Following transfection of indicated plasmids or co-transfection of indicated shRNAs and siRNAs, sizes of HEK293T cells were measured by a Multisizer™ 3 Coulter Counter. Changes in cell size distribution are statistically significant (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p<0.001). (c) and (d) Single liver cell suspensions were freshly prepared from 6-week-old male mice and cell sizes were measured as described in Fig. 2l (mean±SD, n= 4 or 5 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (e) and (f) Livers of 6-week-old male mice were weighed (mean±SD, n=9, 12, or 13 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (g) JNK and mTORC1 signaling were detected by immunoblotting in the same liver tissues described in (f). (h) and (i) Brains of 6-week-old male mice were weighed (mean±SD, n=4 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (j) and (k) Body weights of 6-week-old male mice were measured (mean±SD, n=9, 20, 23, or 24 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (l) and (m) Whole-body composition of 6-week-old male mice was measured (mean±SD, n=9, 10, or 13 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). Statistics source data for Fig. 7d, i can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

To investigate whether this mechanism controls organ and body size, we generated four groups of mice: 1) Hsf1+/+; Jnk1+/+; Jnk2+/+, 2) Hsf1-/-; Jnk1+/+; Jnk2+/+, 3) Hsf1-/-; Jnk1-/-; Jnk2+/+, and 4) Hsf1-/-; Jnk1+/+; Jnk2-/-. Hsf1-/-; Jnk1+/+; Jnk2+/+ mice exhibited reduced liver cell size and liver weight; importantly, either Jnk deletion largely rescued these defects (Fig. 7c-f and Supplementary Fig. 6c). In mouse livers, Hsf1 deletion activated JNK but diminished mTORC1 signaling; and both were reversed by Jnk deletions (Fig. 7g). Importantly, Hsf1 deletion did not reduce HSP90α; by contrast, HSP72 and HSP25 were markedly diminished and this reduction was not rescued by Jnk deficiency (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Together, these results support that in mice HSF1 regulates mTORC1 largely via JNK, independently of HSPs. Jnk deficiency also rescued size defects in Hsf1-/- kidneys and brains (Supplementary Fig. 6e, f and Fig. 7h, i).

Consistent with a previous report45, Hsf1-/- mice exhibited a 20% reduction in body weight and body surface area; strikingly, deletion of either Jnk isoform largely rescued these defects in both sexes (Fig. 7j, k and Supplementary Fig. 6g-i). Furthermore, Jnk deletions fully rescued the lean mass reduction due to Hsf1 deficiency (Fig. 7l and Supplementary Fig. 6j), consistent with rescue of mTORC1 suppression. Unexpectedly, Hsf1 deficiency also reduced body fat mass; however, Jnk deletions failed to rescue this defect (Fig. 7m and Supplementary Fig. 6k). The reduced body fat mass approximately equals the body weight not rescued by Jnk deletions.

Hsf1-/- mice were maintained on a mixed genetic background to circumvent placental defects manifested on inbred backgrounds45. To exclude potential genetic modifiers, we utilized the inbred C57BL/6J Hsf1fl/fl mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a). To achieve liver-specific Hsf1 deletion, we crossed C57BL/6J Albumin-Cre mice with Hsf1fl/fl mice. Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl mice displayed smaller liver size, reduced liver lean mass, and decreased liver cell size; surprisingly, Jnk1 haplodeficiency, but not homozygous deficiency, largely rescued these defects (Fig. 8a-d and Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). However, Jnk1 homozygous deficiency both overly rescued mTORC1 signaling and heightened translation in Hsf1-deficient livers (Fig. 8e, f and Supplementary Fig. 7c). Cell-size homeostasis is the consequence of coordinated cell growth and division46. Thus, we reasoned that altered cell proliferation might counterweigh augmented translation in Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/- livers. We observed an increased in vivo BrdU labeling during the S phase of cell cycle in Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/- liver cells, but not in liver cells from the other three groups (Supplementary Fig. 7d and Fig. 8g). Congruently, c-MYC and MCM2, two known proliferation markers47,48, were increased in Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/-, but not Hsf1-/-;Jnk1-/- or Hsf1-/-;Jnk2-/-, livers (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). Also, apoptosis was enhanced in Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/- livers (Fig. 8h), but not in Hsf1-/-; Jnk1-/- livers (Supplementary Fig. 7g). These results support that despite heightened translation, Jnk1 homozygous deficiency fails to rescue reduced cell size in Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl livers due to enhanced proliferation and apoptosis.

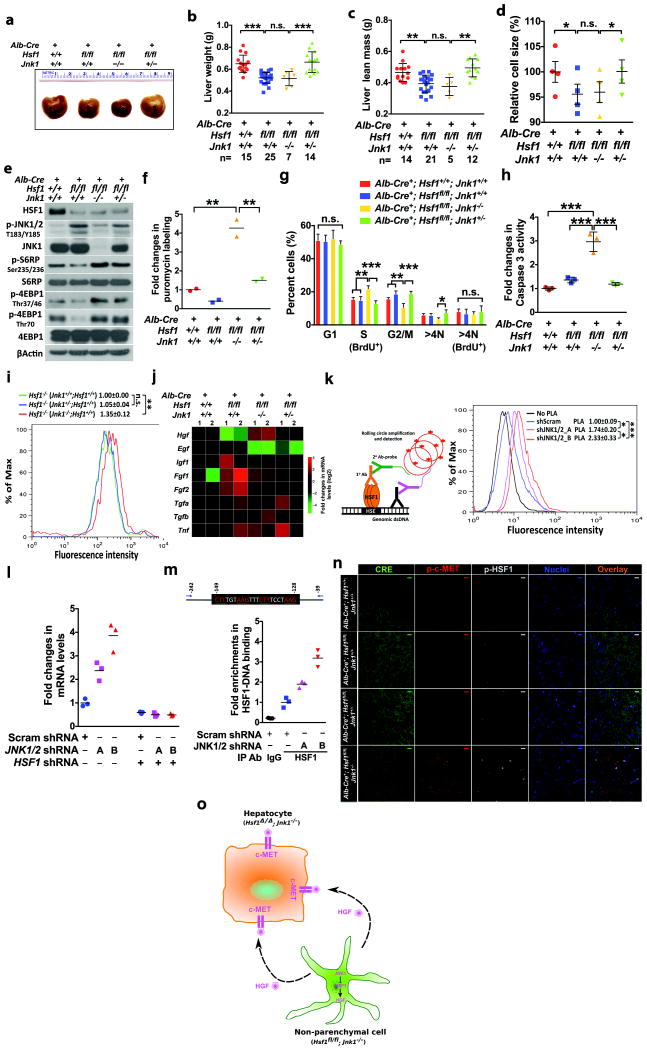

Figure 8. HSF1-JNK interactions regulate liver growth and proliferation.

(a) and (b) Liver weights of 6-week-old male mice (mean±SD, n=7, 14, 15, or 25 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (c) NMR-measured liver lean mass of 6-week-old male mice (mean±SD, n=5, 12, 14, or 21 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (d) Size was measured using single liver cell suspensions from 6-week-old male mice as in Fig. 2l (mean±SEM, n=4 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (e) Livers of 6-week-old male mice were immunoblotted. (f) Liver translation rates were measured in 6-week-old male mice as in Fig. 2n (mean, n= 2 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (g) Following i.p. injection of 2 mg/mouse BrdU for 2 hr, single liver cell suspensions were co-stained with propidium iodide and rat anti-BrdU antibody (mean±SD, n=4 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (h) Caspase 3 activity was quantitated in 6-week-old male mouse livers using DEVD-R110 (mean±SD, n= 3 mice per genotype, One-way ANOVA). (i) Immortalized Hsf1-/- MEFs were co-cultured with primary Jnk1 MEFs (1:1) for 48hr, and co-stained with rabbit anti-Ki-67 and mouse anti-HSF1 antibodies. Ki-67 levels of HSF1-negative cells were compared (mean±SD, n=3 independent experiments, One-way ANOVA). (j) mRNAs in 6-week-old male mouse livers were quantitated by qRT-PCR, 2 mice per genotype. Fold changes were presented as a heat map. (k) Endogenous HSF1 DNA-binding was detected by PLA as described previously11 and quantitated by flow cytometry (mean±SD, n=3 independent experiments, One-way ANOVA). (l) Following shRNA transfection, HGF mRNAs were quantitated in HEK293T cells stably expressing JNK1/2-targeting shRNAs (mean, n=3 wells of cells per group per experiment, repeated three times). (m) HSF1 binding to HGF promoter was quantitated by chromatin IP as described previously12 in HEK293T cells with stable JNK1/2 knockdown (mean, n=3 dishes of cells per group per experiment, repeated twice). (n) Liver cryosections were co-immunostained with anti-p-HSF1 Ser326, anti-p-c-MET Y1234/1235, and anti-Cre antibodies. Scale bars: 10 μm. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. (o) Schematic depiction of the non-cell-autonomous interaction between Hsf1-deficent hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells with activated HSF1. Statistics source data for Fig. 8d, f-i, k-m can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Next we sought to elucidate why proliferation was stimulated in Alb-Cre+;Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/-, but not Hsf1-/-;Jnk1-/-, livers. In Alb-Cre+;Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/- livers Hsf1 is specifically deleted in albumin-expressing hepatocytes, but not in non-parenchymal cells (Supplementary Fig. 7h). By contrast, Hsf1 is deleted in both cell types in Hsf1-/-; Jnk1-/- livers. Therefore, HSF1 expressed in Jnk1-/- non-parenchymal cells might produce non-cell-autonomous effects to drive Hsf1-deficient hepatocyte proliferation. We tested this using an in vitro system, wherein immortalized Hsf1-/- MEFs were co-cultured with primary Jnk1+/+;Hsf1+/+, Jnk1+/-;Hsf1+/+, or Jnk1-/-;Hsf1+/+ MEFs. Interestingly, co-culture with Jnk1-/-;Hsf1+/+, but not with the other, MEFs promoted the proliferation of Hsf1-/- MEFs (Fig. 8i).

To elucidate how Jnk1-/-;Hsf1fl/fl non-parenchymal cells exerted mitogenic effects on Alb-Cre+;Hsf1fl/fl hepatocytes, we quantitated the mRNA levels of a panel of growth factors known to drive hepatocyte proliferation in liver tissues. Among them, only the expression pattern of hepatocyte growth factor (Hgf) concurred with the proliferation state of liver cells, showing elevation in Jnk1-/- livers but nearly normal levels in Jnk1+/- livers (Fig. 8j). A similar pattern was observed in primary MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 7i), indicating suppression of Hgf expression by JNK1. Interestingly, Jnk1-deficient MEFs displayed increased Hsp mRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 7j), suggesting HSF1 activation. Furthermore, JNK1/2 knockdown promoted HSF1-binding to genomic DNAs (Fig. 8k), confirming HSF1 activation by JNK deficiency. HGF mRNAs were increased in HEK293T cells with JKN1/2 knockdown; and, concurrent HSF1 knockdown blocked this increase (Fig. 8l). Moreover, JNK deficiency enhanced HSF1-binding to the HGF gene promoter (Fig. 8m), pinpointing HGF as a transcriptional target of HSF1. Consistently, Jnk1 deficiency failed to rescue diminished Hgf mRNAs in Hsf1-/- livers (Supplementary Fig. 7k). Responding to elevated HGF expression, Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl ; Jnk1-/- livers showed increased phosphorylation of c-MET, the cognate HGF receptor49; by contrast, c-MET phosphorylation did not increase in Hsf1-/-;Jnk1-/- or Hsf1-/-;Jnk2-/- livers (Supplementary Fig. 7l, m). HSF1 activation, evidenced by its Ser326 phosphorylation12, in non-parenchymal cells and c-MET phosphorylation in hepatocytes were confirmed in Alb-Cre+; Hsf1fl/fl ;Jnk1-/- livers by immunostaining (Fig. 8n). Collectively, these results demonstrate that HSF1 controls organ and body size, largely via JNK-dependent mTORC1 regulation. Moreover, these results uncover an HSF1-mediated non-cell-autonomous interaction between hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells (Fig. 8o).

Discussion

Our studies delineate a mechanism whereby cells adapt protein synthesis to stress. While JNK senses proteotoxic stress and directly suppresses mTORC1 to attenuate translation, HSF1 suppresses JNK to sustain translation. Importantly, this mechanism impacts stress resistance and body growth.

Our studies pinpoint JNK as a central nexus linking proteotoxic stress to mTORC1. JNK, activated by various stresses, regulates transcription and apoptosis via phosphorylating numerous targets25. Our findings reveal that JNK constitutively associates with mTORC1; surprisingly, proteotoxic stress does not enhance JNK-RAPTOR associations (Fig. 3a-e), contrasting sharply with the notably induced AMPK-RAPTOR associations by metabolic stress (Fig. 3e). Our findings indicate that JNK activation, a common cellular response to proteotoxic stress, disintegrates mTORC1 at least partially via phosphorylating RAPTOR at Ser863 and mTOR at Ser567 (Fig. 3i-l). Whereas mTORC1 translocates to the lysosome surface in response to amino acid stimulation50, it also senses various other stimuli and localizes at diverse cellular compartments, including nuclei51. Congruently, our findings reveal both cytoplasmic and nuclear JNK-mTORC1 interactions (Fig. 3c, d). Given JNK activation by glucose or amino acid deprivation52,53, whether JNK impacts nutrient-sensing by mTORC1 remains elusive. Also, whether mTORC1 regulates JNK remains unknown. In aggregate, our findings support a model wherein JNK physically associates with mTORC1 in a relatively constitutive manner. Upon activation by proteotoxic stress, JNK phosphorylates both RAPTOR and mTOR, causing partial mTORC1 dissociation. Thereby, mTORC1 serves as a key cellular sensor of proteotoxic stress.

Our studies uncover a transcription-independent role of HSF1 in protein translation. By inactivating and sequestrating JNK, HSF1 sustains mTORC1-mediated translation (Fig. 4). Under our experimental conditions, HSF1 regulates mTORC1, largely independently of HSP90. First, transient HSF1 depletion or Hsf1 knockout does not reduce HSP90 (Fig. 4a, 5a and Supplementary Fig. 6d), due to the high abundance of HSP90 proteins under non-stress conditions and specific regulation of HSP90α isoform by HSF1 under stress54. Second, even with HSP90 inhibition, both wild-type and transcription-deficient HSF1s suppress JNK and activate mTORC1 (Fig. 5f). Nonetheless, in cancer cells where HSF1 is constitutively active and HSP90 is highly demanded55, chronic HSF1 inhibition may deplete HSP90 to impair mTORC1 chaperoning. Of note, compared to the slow transcriptional regulation of HSP90 expression, the rapid regulation of JNK activation enables HSF1 to more efficiently control mTORC1. Surprisingly, our findings reveal context-dependent impacts of HSP90 on JNK signaling. In HEK293T cells, HSP90 inhibition inactivates JNK (Fig. 5a), likely by destabilizing MLK3. As a JNK-activating kinase, MLK3 is chaperoned by HSP90 and overexpressed in malignant cells56,57. By contrast, HSP90 inhibition activates JNK in MEFs (Fig. 5b), suggesting that HSP90 can impact mTORC1, either indirectly through JNK or directly through its chaperoning activity, depending on cellular contexts.

Our findings highlight a key role of HSF1 in maintaining translation at an operational level appropriate for stressful conditions. Whereas mitigated global protein synthesis during stress is beneficial, unrestrained suppression would be adverse. Our studies indicate that mTORC1 controls translation of HSF1 and HSP mRNAs and, accordingly, resistance to proteotoxic stress (Fig. 6). By controlling mTORC1, HSF1 augments expression of itself and HSPs at the translational level. Thus, HSF1 governs the PSR both transcriptionally and translationally.

Our studies reveal that HSF1 intimately coordinates protein synthesis and folding, two processes fundamental to proteostasis. Without HSF1, cells suffer a diminished protein quality-control capacity. Despite their vulnerability to proteomic fluctuations, Hsf1-deficient cells remain viable under non-stress conditions7,45. Now our findings reveal that these deficient cells mitigate mTORC1-mediated translation, thereby lessening the proteomic burden to sustain their fragile proteostasis and viability. However, this adaptive strategy has striking biological consequences, diminishing cell, organ, and body sizes (Fig. 7).

Moreover, our studies uncover a non-cell-autonomous action of HSF1 in promoting proliferation via the HGF-c-MET signaling axis (Fig. 8o). Intriguingly, JNK suppresses both mTORC1 and HSF1, highlighting a role of JNK in proteostasis. Thus, the mutual HSF1-JNK regulations finely orchestrate cellular protein quantity- and quality-control machineries to ensure optimal cellular and organismal growth.

Experimental Methods

Cells, tissues and reagents

HEK293T and HeLa cells were generous gifts from Dr. Luke Whitesell. Primary MEFs were directly derived from mouse embryos. Primary Rosa26-CreERT2; Hsf1fl/fl MEFs were immortalized by stable expression of SV40 large T antigen. All cell cultures were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HEK293T and HeLa cells were used as highly transfectable hosts and have been widely used to study mTORC1 signaling. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms we studied are ubiquitous to all cell types including HEK293T and HeLa cells. These cell lines have not been authenticated and tested for mycoplasma contamination recently.

Rabbit HSP90α (ADI-SPS-771) antibody, HSP72 (ADI-SPA-812) antibody, rabbit HSP25 (ADI-SPA-801) antibody, and rabbit HSP27 (ADI-SPA-803) antibody were from Enzo Life Sciences; rabbit phospho-4EBP1 Thr37 antibody (sc-18080-R), rabbit phospho-4EBP1 Ser65/Thr70 antibody (sc-12884-R), rat monoclonal HSF1 (10H8, sc-13516) antibody, mouse monoclonal HSF1 (E-4, sc-17757) antibody, rabbit HSF1 antibody (H-311, sc-9144), mouse monoclonal JNK (D-2, sc-7345) antibody, rabbit JNK1/3 (C-17, sc-474) antibody, mouse monoclonal p38α/β (A-12, sc-7972) antibody, mouse monoclonal dsDNA marker antibody (HYB331-01, sc-58749), and rabbit c-MYC (N-262, sc-764) antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; antibodies for phospho-p70S6K Thr389 (108D2, #9234), p70 S6K (49D7, #2708), phospho-S6 ribosomal protein Ser235/236 (D57.2.2E, #4858), S6 ribosomal protein (5G10, #2217), phospho-c-JUN ser73 (D47G9, #3270), c-JUN (60A8, #9165), phospho-4EBP1 Thr37/46 (236B4, #2855), phospho-4EBP1 Thr70, 4E-BP1 (53H11, #9644), phospho-mTOR Ser2481 (#2974), mTOR (7C10, #2983), RAPTOR (24C12, #2280), RICTOR (53A2, #2114), GβL (86B8, #3274), PRAS40 (D23C7, #2691), phospho-JNK1/2 Thr183/Tyr185 (81E11, #4668), JNK2 (56G8, #9258), phospho-p38 MAPK Thr180/Tyr182, phospho-AMPKα Thr172 (40H9, #2535), AMPKα (23A3, #2603), phospho-ULK1 Ser757 (D7O6U, #14202), ULK1 (D8H5, #8054), MKK7 (#4172), cleaved caspase 3 Asp175 (D3E9, #9579), MCM2 (D7G11, #3619), phospho-c-MET (Tyr1234/1235) (D26) and its biotin conjugate (#3077, 4033), c-MET (25H2, #3127), and GST tag (91G1, #2625) antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies; mouse c-Myc tag monoclonal antibody (A00704), HA-tag antibody-HRP (A00169), βActin antibody-HRP (A00730), GAPDH antibody-HRP (A00192), and FLAG antibody-HRP (A01428) conjugates were from GenScript. Rabbit HA tag antibody (GTX115044), and rabbit monoclonal phospho-HSF1 Ser326 (EP1713Y, GTX61682) antibody were purchased from GeneTex. Anti-Lys48-specific ubiquitin antibody (Apu2, #05-1307), mouse monoclonal anti-RAPTOR antibody (1H6.2, #05-1470), mouse monoclonal anti-mTOR antibody (2ID8.2, #05-1592), rabbit anti-phospho-RAPTOR Ser863 antibody (#09-106), and rabbit anti-Ki-67 antibody (AB9260) were purchased from EMD Millipore. Mouse monoclonal anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibody (PM3801) and mouse monoclonal anti-JNK1 antibody (JM2671) were purchased from ECM Biosciences. Rat monoclonal anti-HSF1 antibody cocktail (4B4+10H4+10H8, ab81279) was purchased from Abcam. Anti-Cre recombinase antibody DyLight™ 488 conjugate (LS-C180307) was purchased from LifeSpan Biosciences. Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-mTOR Ser567 antibody was generated through a custom antibody production service from AnaSpec Inc. CF594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (#20112) and CF594 goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) (#20155) secondary antibody conjugates were purchased from Biotium. DyLight™488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (#35552) and DyLight™550 streptavidin conjugates (#84542) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. PE goat anti-mouse Ig secondary conjugate (#550589) was purchased from BD Biosciences. Alexa Fluor®594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (A-11005) or Alexa Fluor®568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (A-11011) secondary antibody conjugates were purchased from Life Technologies.

Phosphorylated S6K and JNK proteins were quantitated by ELISA using PathScan® Phospho-p70 S6 Kinase (Thr389) (#7053) and Phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (#7217) Sandwich ELISA antibody pairs purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The following chemicals were purchased from commercial sources: (S)-MG132 (Cayman Chemical), VER155008, Pifithrin-μ, and SB202190 (Tocris Bioscience), 17-DMAG (LC Laboratories), rapamycin and Velcade (LC Laboratories), JNK-IN-8 and AZD8055 (Selleckchem), tubastatin A (ChemieTek), azetidine (Bachem Americas), (Z)-4-Hydroxytamoxifen (LKT Laboratories), and puromycin (InvivoGen).

Ad5CMVhr-GFP and Ad5CMVCre viral particles (1-5×1010 pfu/ml) were obtained from the University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core.

The plasmids used in this study include: pLenti6-LacZ-V5 from Life Technologies; HA-RAPTOR, FLAG-RAPTOR, Myc-mTOR, and FLAG-mTOR were gifts from David Sabatini (Addgene#8513, 26633, 1861, and 26603); FLAG-JNK1CA (MKK7B2JNK1A1), FLAG-JNK1DN (APF mutant), FLAG-JNK2A2, and FLAG-JNK1A1 were gifts from Roger Davis (Addgene#19726, 13846, 13755, and 13798); pHSE-SEAP (Clontech Laboratories Inc.); and pCMV-Gaussia luciferase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). pLenti6-FLAG-HSF1 was constructed from pBabe-FLAG-HSF1, a gift from Carl Wu (Addgene#1948). FLAG-HSF11-379, FLAG-HSF1AD, HA-RAPTORS863A, and Myc-mTORSer567A mutants were constructed using a Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs Inc.).

Antibody array experiment

Changes in phosphorylation of key signal transducers following heat shock were profiled using a PathScan® Intracellular Signaling Array Kit (#7744, Cell Signaling Technology), according to the manufacture's instructions. Protein lysates of HEK293T cells with and without heat shock were incubated with antibody arrays and the final fluorescent images were captured using a LI-COR® Bioscience Odyssey® Imaging system. Fluorescent signals were quantitated by ImageJ software.

Proximity Ligation Assay

Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature (RT). After blocking with 5% normal goat serum in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, primary antibodies 1:100 diluted in blocking buffer were incubated with fixed cells overnight at 4°C. Following incubation with Duolink® PLA® anti-rabbit Plus and anti-mouse Minus probes (1:5 dilution, OLINK Bioscience) at 37°C for 1hr, ligation, rolling circle amplification, and detection were performed using the Duolink® In Situ Detection Reagents Red (OLINK Bioscience). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. PLA signals were documented by a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope or quantitated by flow cytometry.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted using RNA STAT-60 reagent (Tel-Test, Inc.), and RNAs were used for reverse transcription using a Verso cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of cDNA were used for quantitative RCR reaction using a DyNAmo SYBR Green qPCR kit (Thermo Scientific). Signals were detected by an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). ACTB was used as the internal control. The sequences of individual primers for each gene are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Transfection and luciferase reporter assay

Plasmids were transfected with TurboFect transfection reagent (Thermo Scientific). siRNAs were transfected at 10 nM final concentration with MISSION® siRNA Transfection Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). shRNA and siRNA co-transfections were performed using JetPRIME® reagents (Polyplus Transfection). SEAP and luciferase activities in culture supernatants were quantitated using a Ziva® Ultra SEAP Plus Detection Kit (Jaden BioScience) and a Gaussia Luciferase Glow Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific), respectively. Luminescence signals were measured by a VICTOR3 Multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Whole-cell protein extracts were prepared in cold cell-lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and Halt™ protease inhibitor cocktail from Thermo Scientific). Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Primary antibodies, except p-mTOR Ser567 antibody (1:100 dilution), were applied in wash buffer (1:1,000 dilution) overnight at 4°C. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1: 2,500 dilution, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were applied at room temperature (RT) for 1 hr, and signals were visualized by SuperSignal West chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) followed by exposure to films.

For mTORC1 immunoprecipitation, cells grown to 80% confluence were washed with PBS twice and re-suspended in ice-cold sonication buffer (20 mM Tris, 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM β-glycerol-phosphate, 20 mM sodium fluoride, 4 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mM DTT pH7.4, supplemented with Halt™ protease inhibitor cocktail). Cells were lysed three times in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes on ice using a Sonicator 3000 Ultrasonic Cell Disruptor (Misonix Inc.) with the following settings (total process time: 15S, pulse-on time: 5S, pulse-off time: 10S, initial output level: 0.5). Total 800-1000 μg proteins in 400 μl were incubated with 2.5 μg primary antibodies, including mouse monoclonal anti-Raptor (clone 1H6.2), anti-mTOR (clone 21D8.2), HA tag (GTX115044), or Myc tag (A00704) antibodies, and 20 μl Protein G MagBeads (GenScript) at 4°C overnight. Following washing three times with sonication buffer, 50 μl 2× sample buffer containing 3% 2-mercaptoethanol was added to the beads, and the mixtures were boiled for 5 min before loading for SDS-PAGE.

Puromycin-labeling ELISA

100 μg proteins were coated in each well of an ELISA plate at 4°C overnight. After blocking with SuperBlock™ blocking buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific), each well was incubated with 1:1,000 diluted mouse monoclonal anti-puromycin antibody (clone 3RH11, EQ0001, KeraFAST) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with 1:2,500 diluted goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)-HPR conjugates at RT for 1 hr. Signals were developed using 1-Step Ultra TMB ELISA Substrate (Thermo Scientific Pierce).

In vitro kinase assay

For mTORC1 kinase assays, cells were washed with PBS and re-suspended in ice-cold sonication buffer without 1 mM EDTA and sonicated as described above. Total 1 mg proteins in sonication buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail were incubated with 1 μg primary antibodies and 20 μl Protein G MagBeads (GenScript) at 4°C overnight. Precipitated beads were washed once with 500 μl high-salt kinase washing buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.4, 20 mM KCl, 500 mM NaCl) followed by washing with kinase washing buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH7.4, 20 mM KCl) for twice. Washed beads were incubated with 30 μl mTOR kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES pH7.4, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 250 μM ATP) and 100 ng recombinant human His-ElF4EBP1 proteins (Fitzgerald Industries International) at 30°C for 30 min with 1,200 rpm mixing in an Eppendorf ThermoMixer®. Reactions were stopped by adding 20 μl 2× sample buffer with 3% 2-mercaptoethanol.

For JNK kinase assays, cells were lysed through sonication as described above. Total 1 mg proteins in sonication buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail were incubated with 1 μg primary antibodies and 20 μl Protein G MagBeads (GenScript) at 4°C overnight. Precipitated beads were washed three times with 500 μl kinase washing buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.4, 20 mM KCl). Washed beads were incubated with 30 μl JNK kinase buffer (25 mM MOPS pH7.2, 12.5 mM β-glycerol-phosphate, 25 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 0.25 mM DTT, 250 μM ATP) and 100 ng recombinant GST or GST-JNK1 active protein (SignalChem) at 30°C for 30 min with 1,200 rpm mixing in an Eppendorf ThermoMixer®. Reactions were stopped by adding 20 μl 2× sample buffer with 3% 2-mercaptoethanol.

shRNA and siRNA knockdown

Lentiviral pLKO shRNA plasmids targeting human HSF1 were obtained from the Broad Institute RNAi platform: HSF1:TRCN0000007480 (hA6), TRCN0000007483 (hA9). Control hairpins targeting a scrambled sequence with no known homology to any human genes (Scram; 5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG-3′) have been described previously7. pLKO shRNA plasmids targeting human JNK1/MAPK8 and JNK1/MAPK9 were purchased from Dharmacon GE Healthcare: shJNK1_2 (TRCN0000001056), shJNK1_4 (TRCN0000010580), shJNK2_1 (TRCN0000000945), and shJNK2_2 (TRCN0000000946). MISSION® siRNAs: siJNK1_2 (SIHK1220), siJNK1_3 (SIHK1221), siJNK2_2 (SIHK1223), siJNK2_3 (SIHK1224), siMKK7_1 (SIHK1114), siMKK7_2 (SIHK1115), and siMKK7_3 (SIHK1116) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The non-targeting siRNA control (D-001810-01) was purchased from Dharmacon GE Healthcare.

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell viability and numbers were measured in 96-well microplate format using ViaCount® reagents by a Guava® EasyCyte flow cytometer (Millipore). Apoptosis was detected by either immunoblotting using anti-cleaved caspase 3 Asp175 (D3E9) antibodies (Cell Signaling Technologies) or a Caspase 3 DEVD-R110 Fluorometric and Colorimetric Assay kit (Biotium).

Measurement of liver cell size

Mechanically dissociated mouse livers in PBS supplemented with 10% FBS were squeezed through 70μm nylon cell strainers with syringe heads. Single-cell suspensions were collected and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 minutes. After washing three times with PBS-FBS, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and the primary cell populations were gated for size measurement based on forward scatter.

Isolation of polysome-bound mRNAs

Following incubation with fresh media containing cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) for 1 minute, cells were rinsed with 10 ml cold PBS supplemented with cycloheximide. After adding 500 μl of cold polysome lysis Buffer (20vmM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, and 1% triton-100) to the plate, cells were scraped and incubated for 10 minutes on ice. Following centrifugation for 10 minutes at 15,000 × g at 4°C, 100μl supernatants were applied to Sephacryl S400 columns (Illustra MicroSpin S-400 HR, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to isolate polysomes. Flow-through fractions were collected and mixed with 100 μl of polysome buffer and 20 μl of 10% SDS. Polysome-bound RNAs were extracted using RNA STAT-60 reagent (Tel-Test Inc.).

BrdU labeling of liver cells

Each mouse was i.p. injected with 200 μl of sterile BrdU solution (10 mg/ml). After 2 hours, livers were harvested to prepare single-cell suspensions in PBS using 40 μm cell strainers. Cells were slowly added to 70% ethanol at -20°C with continuous vortex followed by 30-minute incubation on ice. To denature DNAs, re-suspended cells were treated with 2N HCl containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and incubated at RT for 30 minutes. After washing with PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20, cells were incubated with 1:100 diluted rat anti-BrdU antibodies (clone BU1/75, MCA2060, AbD Serotec) at RT for 45 minutes followed by incubation with 1:200 diluted goat anti-Rat IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor®488 conjugates (A-11006, Life Technologies). After washing, cells were stained with PBS containing 10 μg/ml of PI before flow cytometry analysis.

Immunofluorescence

For IF on cultured cells, primary antibodies were 1:100 diluted in 5% normal goat serum. For IF on frozen liver sections, anti-p-HSF1 Ser326 antibody was 1:100 diluted in 5% normal goat serum and further detected by CF594-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (pseudo-colored as gray), biotinylated anti-p-c-MET (Y1234/1235) antibody was 1:50 diluted and detected by DyLight™ 550 conjugated streptavidin, and DyLight™ 488 conjugated with anti-Cre antibody was 1:100 diluted. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, and all conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution) were incubated at RT for 1 hr. Fluorescent signals were captured using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and images of different fluorescence channels were overlaid using the ImageJ software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP experiments were performed as described previously11 using rabbit anti-HSF1 antibodies (H-311, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or normal rabbit IgG. The sequences of individual primers for CHIP-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Image analysis

Immunoblotting signals were quantitated by ImageJ software.

Animal studies

C57BL/6 Jnk1 and Jnk2 heterozygous mice58, 59 were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Hsf1+/- mice were maintained on a mixed 129SvJ/BALB/cJ background45. Compound F2 mutant mice of both Hsf1 and Jnk genes were intercrossed to generate progenies for analyses. C57BL/6J Hsf1fl/fl mice were generated by homologous recombination. A targeting vector was constructed to contain 3648 bp 5′ homology arm, loxP-flanked Hsf1 exon2-9, a FRT flanked PGK-neo cassette, and 3580bp 3′ homology arm. The linearized targeting vector was electroporated into B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J (albino C57BL/6J) ES cells. Correctly targeted ES cells were microinjected into C57BL/6J blastocysts. Chimeras were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice to achieve germline transmission. To remove the PGK-neo cassette, C57BL/6J Rosa26-FLP1 knock-in mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with Hsf1fl/fl mice. Genotyping was performed by PCR using tail genomic DNAs. The genotyping primers are: P1 (5′-GGGTATGGGGGACTTTTAGG-3′), P2 (5′-AGTGAGGCCCATGTAACCAG-3′), and P3 (5′-TCCTCCTCCCTCCCAAGTGGG-3′). C57BL/6J Rosa26-CreERT2 mice60, C57BL/6J Albumin-Cre mice61, and Tsc1fl/fl mice62 on a mixed background were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. All mouse experiments were performed under a protocol approved by The Jackson Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurement of global protein translation in vitro and in vivo

Cells were incubated with 6-FAM-dc-puromycin (50 nM, Jena Bioscience) in vitro for 1h and analyzed by flow cytometry. For in vivo puromycin labeling, mice were i.p. injected with 100 μl puromycin (10 mg/ml) 2hr before harvesting tissues. Puromycin-labeled proteins in mouse tissues were quantitated by direct ELISA using anti-puromycin antibodies (clone 3RH11, #EQ0001, KeraFast).

HSF1 protein translation

Cells were labeled with biotin-dc-puromycin (100 nM, Jena Bioscience) for 3hr and cell lysates were incubated in microtiter plates coated with a cocktail of HSF1 antibodies (H-311, E-4, and 10H8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. After washing, captured puromycin-labeled HSF1 proteins were detected using streptavidine-HRP conjugates (GenScript).

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based body composition analysis

Body composition of live mice was measured using an EchoMRI-130™ whole body composition analyzer (EchoMRI LLC) according to manufacture's instructions.

Statistics and Reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad software). Unpaired two-tailed student's t test was used to compare two groups; and an F-test was used to determine equality of variances. One-way or two-way ANOVA was used to compare multiple groups. Sample sizes are listed in the figures or figure legends. All results are presented as mean ± SD, unless otherwise noted. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No samples or animals were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. For animal studies, due to the necessity of genotyping the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

The in vivo mouse studies (Figs. 2k, m-p, 7c-f, 7h-m, 8a-d, g, h, and Supplementary Figs. 2m-o, 6c, e-k, 7a, b) and Figs. 8i, k are the sum results of accumulated at least 3 individual mice or independent experiments; and Fig. 8f is the sum results of accumulated 2 individual mice. Among the representative images: Figs. 1b, c, h, i, 2a-j, l, 3a-l, 4a-f, 5a, b, e, f, 6a, f, g, 7g, 8e, n and Supplementary Figs. 1c, d, 2a, b, e-l, 3f-j, 4d, e, 6a, b, d, 7e, f, l, m have been reproduced at least 3 times; and Supplementary Figs. 3a-d, 4c, 7h have been reproduced 2 times. All the other experiments have been reproduced at least 2 times, except Figs 1a and Supplementary Figs. 1b, 2c, d, 4b, which are from one experiment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Dai laboratory for their discussions and technical assistance. This work was supported by the grant from NIH (1DP1OD006438) to I.J.B., The Jackson Laboratory Cancer Center Support Grant (3P30CA034196), grants from NIH (1DP2OD007070) and the Ellison Medical Foundation (AS-NS-0599-09) to C.D..

Footnotes

Author Contributions: K. –H. S., J. C., Z. T., and S. D. designed and performed the experiments. Y.H. performed statistical analyses and generated graphs. I.J. B. provided mice and cell lines and actively engaged in discussions. C.D. conceived and oversaw this study. S.B.S. and C.D. wrote the manuscript.

Completing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morimoto RI. The heat shock response: systems biology of proteotoxic stress in aging and disease. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:91–99. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.76.010637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morimoto RI. Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1427–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1657108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai C, Dai S, Cao J. Proteotoxic stress of cancer: implication of the heat-shock response in oncogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2982–2987. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Min JN, Huang L, Zimonjic DB, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Selective suppression of lymphomas by functional loss of Hsf1 in a p53-deficient mouse model for spontaneous tumors. Oncogene. 2007;26:5086–5097. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, Lindquist S. Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell. 2007;130:1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng L, Gabai VL, Sherman MY. Heat-shock transcription factor HSF1 has a critical role in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-induced cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29:5204–5213. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin X, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Heat shock transcription factor 1 is a key determinant of HCC development by regulating hepatic steatosis and metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2011;14:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai C, et al. Loss of tumor suppressor NF1 activates HSF1 to promote carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3742–3754. doi: 10.1172/JCI62727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai S, et al. Suppression of the HSF1-mediated proteotoxic stress response by the metabolic stress sensor. AMPK Embo J. 2015;34:275–293. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Z, et al. MEK Guards Proteome Stability and Inhibits Tumor-Suppressive Amyloidogenesis via HSF1. Cell. 2015;160:729–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindquist S. Regulation of protein synthesis during heat shock. Nature. 1981;293:311–314. doi: 10.1038/293311a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwinn DM, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:935–945. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sancak Y, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derijard B, et al. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawaguchi Y, et al. The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell. 2003;115:727–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00939-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leu JI, Pimkina J, Frank A, Murphy ME, George DLA. small molecule inhibitor of inducible heat shock protein 70. Mol Cell. 2009;36:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massey AJ, et al. A novel, small molecule inhibitor of Hsc70/Hsp70 potentiates Hsp90 inhibitor induced apoptosis in HCT116 colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:535–545. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickart CM, Eddins MJ. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang T, et al. Discovery of potent and selective covalent inhibitors of JNK. Chem Biol. 2012;19:140–154. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manning AM, Davis RJ, Targeting JNK. for therapeutic benefit: from junk to gold? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:554–565. doi: 10.1038/nrd1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:689–737. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiger PC, Wright DC, Han DH, Holloszy JO. Activation of p38 MAP kinase enhances sensitivity of muscle glucose transport to insulin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E782–788. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00477.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, et al. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hara K, et al. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell. 2002;110:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soliman GA, et al. mTOR Ser-2481 autophosphorylation monitors mTORC-specific catalytic activity and clarifies rapamycin mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7866–7879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta S, et al. Selective interaction of JNK protein kinase isoforms with transcription factors. Embo J. 1996;15:2760–2770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lei K, et al. The Bax subfamily of Bcl2-related proteins is essential for apoptotic signal transduction by c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4929–4942. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4929-4942.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lei K, et al. The Bax subfamily of Bcl2-related proteins is essential for apoptotic signal transduction by c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4929–4942. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4929-4942.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Xu Y, Stoleru D, Salic A. Imaging protein synthesis in cells and tissues with an alkyne analog of puromycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:413–418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111561108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J. Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4. E Genes Dev. 2002;16:1472–1487. doi: 10.1101/gad.995802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Um SH, D'Alessio D, Thomas G. Nutrient overload, insulin resistance, and ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, S6K1. Cell Metab. 2006;3:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirosumi J, et al. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clausson CM, et al. Increasing the dynamic range of in situ. PLA Nat Methods. 2011;8:892–893. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosner M, Hengstschlager M. Cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of the protein complexes mTORC1 and mTORC2: rapamycin triggers dephosphorylation and delocalization of the mTORC2 components rictor and sin1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2934–2948. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogoyevitch MA, Kobe B. Uses for JNK: the many and varied substrates of the c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:1061–1095. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00025-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qian SB, et al. mTORC1 links protein quality and quantity control by sensing chaperone availability. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27385–27395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.120295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jez JM, Chen JC, Rastelli G, Stroud RM, Santi DV. Crystal structure and molecular modeling of 17-DMAG in complex with human Hsp90. Chem Biol. 2003;10:361–368. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of m. TOR Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao X, et al. HSF1 is required for extra-embryonic development, postnatal growth and protection during inflammatory responses in mice. Embo J. 1999;18:5943–5952. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jorgensen P, Tyers M. How cells coordinate growth and division. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R1014–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eilers M, Eisenman RN. Myc's broad reach. Genes and Development. 2008;22:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.1712408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freeman A, et al. Improved detection of hepatocyte proliferation using antibody to the pre-replication complex: an association with hepatic fibrosis and viral replication in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:345–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goyal L, Muzumdar MD, Zhu AX. Targeting the HGF/c-MET pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2310–2318. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sancak Y, et al. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Betz C, Hall MN. Where is mTOR and what is it doing there? J Cell Biol. 2013;203:563–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cui H, et al. Enhanced expression of asparagine synthetase under glucose-deprived conditions protects pancreatic cancer cells from apoptosis induced by glucose deprivation and cisplatin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3345–3355. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaveroux C, et al. Identification of a novel amino acid response pathway triggering ATF2 phosphorylation in mammals. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6515–6526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00489-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trepel J, Mollapour M, Giaccone G, Neckers L. Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:537–549. doi: 10.1038/nrc2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang H, et al. Hsp90/p50cdc37 is required for mixed-lineage kinase (MLK) 3 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19457–19463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen J, Miller EM, Gallo KA. MLK3 is critical for breast cancer cell migration and promotes a malignant phenotype in mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:4399–4411. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dong C, et al. Defective T cell differentiation in the absence of Jnk1. Science. 1998;282:2092–2095. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang DD, et al. Differentiation of CD4+ T cells to Th1 cells requires MAP kinase JNK2. Immunity. 1998;9:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ventura A, et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Postic C, et al. Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic beta cell-specific gene knock-outs using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:305–315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:525–534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.