Abstract

Development of anti-cancer drugs towards clinical application is costly and inefficient. Large screens of drugs, efficacious for non-cancer disease, are currently being used to identify candidates for repurposing based on their anti-cancer properties. Here, we show that low-dose salinomycin, a coccidiostat ionophore previously identified in a breast cancer screen, has anti-leukemic efficacy. AML and MLLr cell lines, primary cells and patient samples were sensitive to submicromolar salinomycin. Most strikingly, colony formation of normal hematopoietic cells was unaffected by salinomycin, demonstrating a lack of hemotoxicity at the effective concentrations. Furthermore, salinomycin treatment of primary cells resulted in loss of leukemia repopulation ability following transplantation, as demonstrated by extended recipient survival compared to controls. Bioinformatic analysis of a 17-gene signature identified and validated in primary MLLr cells, uncovered immunomodulatory pathways, hubs and protein interactions as potential transducers of low dose salinomycin treatment. Additionally, increased protein expression of p62/Sqstm1, encoded for by one of the 17 signature genes, demonstrates a role for salinomycin in aggresome/vesicle formation indicative of an autophagic response.

Together, the data support the efficacy of salinomycin as an anti-leukemic at non-hemotoxic concentrations. Further investigation alone or in combination with other therapies is warranted for future clinical trial.

Keywords: drug repurposing, salinomycin, anti-leukemia, gene signature, AML/MLL-rearrangements

INTRODUCTION

Drug repurposing (or repositioning) has become a tactic to deploy approved weaponry in the war on cancer, resulting in the development of defined projects [1]. The concept of drug repurposing is borne from a demand to complement and accelerate current drug development strategies, which are often costly, inefficient, [2, 3] and in the case of anti-cancer therapies, can take over 8 years to obtain approval for clinical use [4]. This potential drug development ‘crisis’ is occurring at the same time as increased cancer incidence due in part to an aging society, altered lifestyles and diet in developing countries [5, 6].

Salinomycin is a polyether organic anion that is widely used as a coccidiostatic antibiotic in poultry and ruminant feed. Salinomycin was identified in a chemical screen by Gupta et al to target breast cancer stem cells (CSCs) [7], and has subsequently shown anti-neoplastic properties in a range of human cancers, including hematological malignancies (reviewed by Zhou et al) [8], though it's activity in acute leukemia remains unexplored. We previously used Connectivity Mapping to identify candidate drugs, including an antibiotic, for repurposing as anti-leukemic agents [9].

As an antibiotic, salinomycin primarily acts as an ionophore, facilitating transportation of cations (e.g. Ca2+ and K+) across membranes resulting in toxic intracellular levels [10, 11]. As an anti-cancer agent, salinomycin has been reported to activate several pathways including apoptosis in a p53/Caspase/CD95/DC95L/ proteasome independent manner, increase DNA damage, and inhibit Wnt signalling, preferentially in malignant CSCs [12–15]. However, the precise mechanism of action of salinomycin in distinct CSCs remains to be elucidated. One recognized limitation for clinical application of salinomycin is a relatively narrow therapeutic index, giving rise to potential related toxicities [16–18] and potential impairment of normal stem cell function, particularly within the hematopoietic system.

To gain further insight into possible clinical application for hematological malignancies, we examined and demonstrated the anti-leukemic potential of low-dose salinomycin in pre-clinical models of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and poor prognosis Mixed Lineage Leukemia-rearranged (MLLr) subtypes, whilst concurrently demonstrating negligible toxicity to normal blood cells.

RESULTS

Differential sensitivity of human AML cell lines to Salinomycin

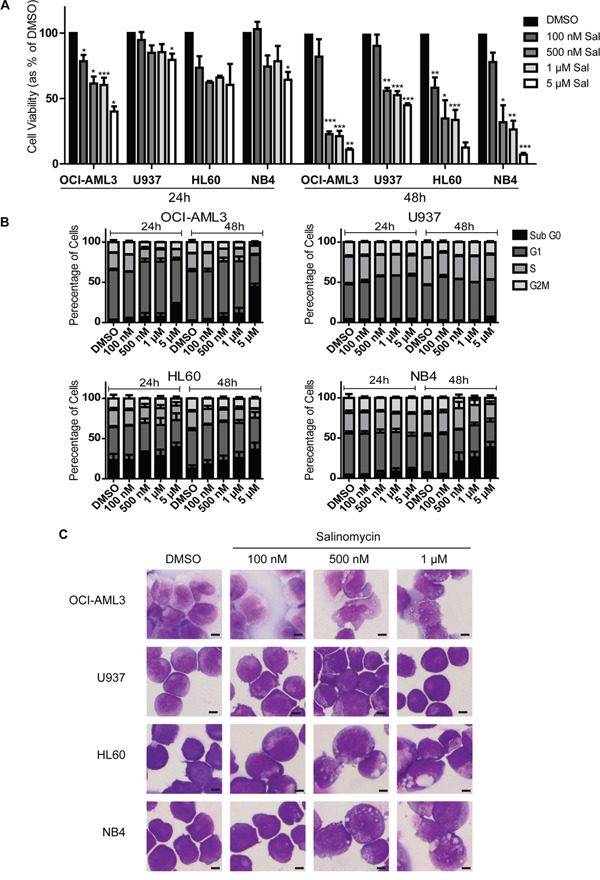

AML cell lines demonstrated reduced cell viability following salinomycin treatment (100 nM - 5 μM), with OCI-AML3 cells demonstrating greatest and U937 cells least sensitivity, particularly at the 24 hour time point (Figure 1A and Supplementary Table S1). Reduced cell viability was associated with an accumulation of cells in the Sub G0 phase of the cell cycle as determined by direct DNA staining (Figure 1B) with only limited related changes in Caspase activity (Supplementary Figure S1, upper panel). Although U937 cells demonstrated little increase in the Sub G0 population, some alteration in cell cycle progression, primarily reduction of cells in S-phase, was observed.

Figure 1. Differential sensitivity of human AML cell lines to salinomycin.

A. Bar graphs showing decreased viability in AML cell lines over time following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage compared to 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. B. Bar graphs showing altered cell cycle (Propidium Iodide staining) in AML cell lines over time following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage or 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. C. Representative morphology images of AML cell lines treated for 48 hours with salinomycin at the indicated dosages or 0.01% DMSO. Mean values ± S.E.M. of biological replicates (n=3) are plotted throughout. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, t-test. Scale bar = 4 μm.

To further examine the effects of salinomycin, AML cells were exposed to low concentrations (≤1 μM) for 48 hours and examined microscopically. Three of the cell lines demonstrated significant alterations in morphology in a dose-dependent manner, ranging from loss of nuclear shape at low dose exposure (100 nM, HL60) to the formation of cytoplasmic vesicles at higher dosages (500 nM, OCI-AML3, HL60 and NB4). Consistent with the cell viability and cell cycle assays, U937 cells demonstrated no morphological changes compared to DMSO controls (Figure 1C).

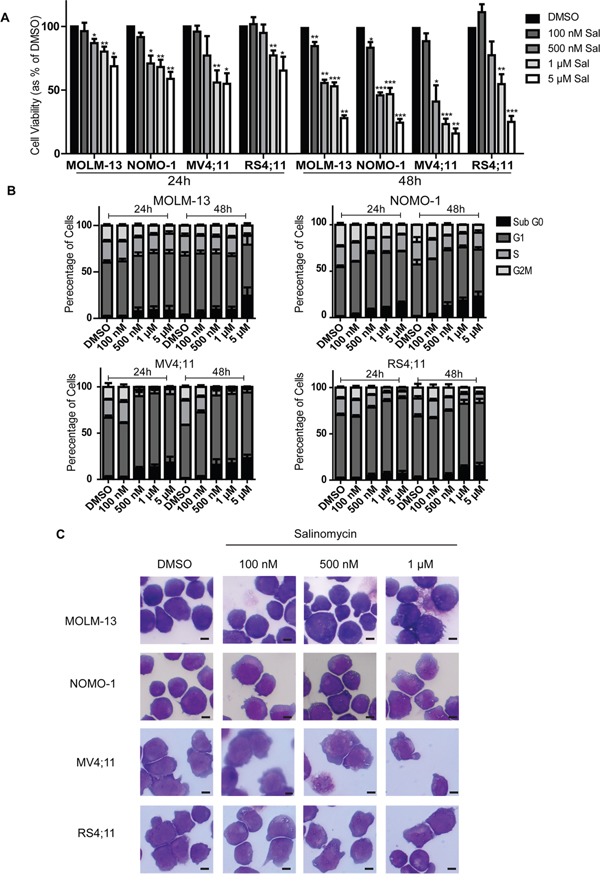

Salinomycin alters growth and morphology of MLLr cell lines

All four MLLr cell lines were sensitive to salinomycin over the same dose and time used for the AML cell lines, indicative of a biological response (Figure 2A and Supplementary Table S1). Increases in Sub G0 were associated with decreases in S-phase populations (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S2 upper), and increased Annexin V expression (Supplementary Figure S2) was associated with limited change in Caspase activity, restricted to 1 μM treatment of MV4;11 cells (Supplementary Figure S1, lower panel). Microscopic examination showed similar morphological changes as observed for AML cells, including the presence of vesicles in all MLLr cell lines following 500 nM salinomycin treatments (Figure 2C). Overt vesicle formation in three of the MLLr cell lines examined (MOLM-13, NOMO-1 and RS4;11) was observed even at 100 nM salinomycin compared to vehicle controls, indicating increased sensitivity in these cell lines.

Figure 2. Salinomycin alters growth and morphology of MLLr cell lines.

A. Bar graphs showing decreased viability in MLLr cell lines over time following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage compared to 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. B. Bar graphs showing altered cell cycle (Propidium Iodide staining) in MLLr cell lines over time following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage or 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. C. Representative morphology images of MLLr cell lines treated for 48 hours with salinomycin at the indicated dosages or 0.01% DMSO. Mean values ± S.E.M. of biological replicates (n=3) are plotted throughout. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, t-test. Scale bar = 4 μm.

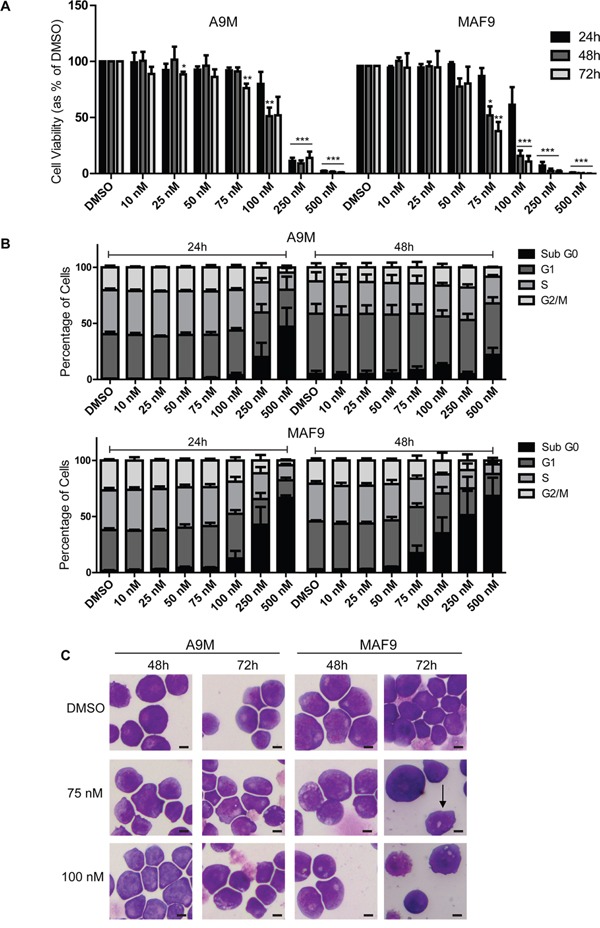

Salinomycin-sensitive primary murine AML and MLLr leukemia cell lines

To further examine the potential anti-leukemic effect of salinomycin, studies were extended into two growth factor-dependent primary murine cell lines A9M and MAF9, generated by retroviral transduction of HOXA9-ires-Meis1(A9M) or MLL-AF9 (MAF9) into primary haematopoietic cells, as previously reported [9], followed by serial replating in methylcellulose. Due to anticipated increased sensitivity in the primary cells, an extended lower dose range (10 - 500 nM) was used. Both primary cell lines demonstrated reduced cell viability at 250 nM and 500 nM salinomycin at both early (24 hour) and late (72 hour) time points (Figure 3A). Lower dose salinomycin (75 nM and 100 nM) resulted in differential time and cell line response, with the MAF9 cells demonstrating greater sensitivity and lower estimated IC50s (Supplementary Figure S3). The decreased cell viability was matched with dramatic changes in cell cycle, in particular increased Sub G0 and decreased S and G2M populations at higher doses (Figure 3B). Consistent with the cell viability assays, cell cycle responses were more striking in MAF9 (lower panel) than A9M cells (upper panel). Since higher doses of salinomycin resulted in significant cell loss, cell morphology analysis in A9M and MAF9 cells was restricted to lower concentrations (75 nM and 100 nM) for up to 72 hours. Morphological changes, including the presence of vesicles, were observed for both cell lines in a time and dose-dependent manner. Interestingly, MAF9 cells also demonstrated the presence of band neutrophils at the 72 hour time point (75 nM), indicative of differentiation (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Salinomycin-sensitive primary murine AML and MLLr leukemia cell lines.

A. Bar graphs showing decreased viability in A9M and MAF9 primary leukemia cell lines over time following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage compared to 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. B. Bar graphs showing altered cell cycle (Propidium Iodide staining) in A9M and MAF9 primary leukaemia cell lines over time following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage or 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. C. Representative morphology images of A9M and MAF9 primary leukaemia cell lines treated for 48 and 72 hours with salinomycin at the indicated dosages or 0.01% DMSO. Band neutrophil is highlighted with an arrow. Mean values ± S.E.M. of biological replicates (n=4) are plotted throughout. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, t-test. Scale bar = 4 μm.

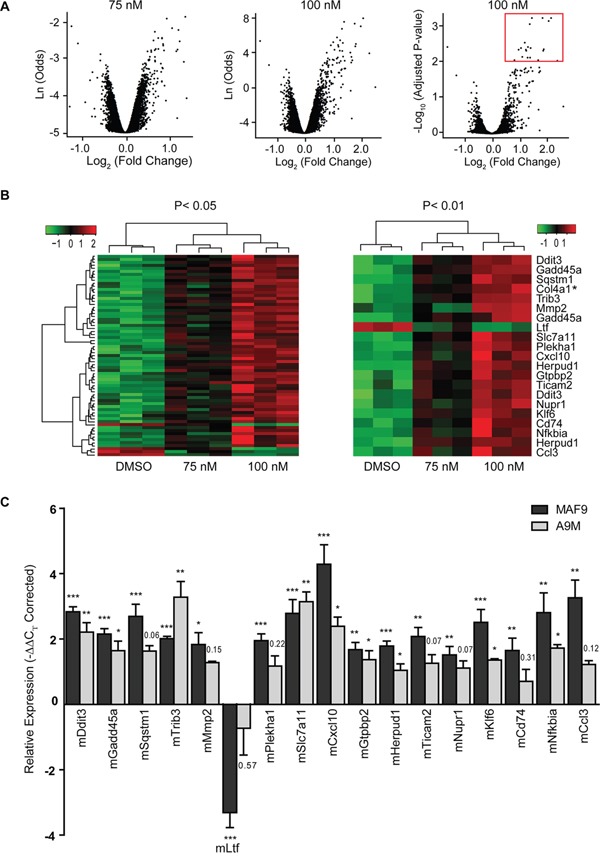

Salinomycin-induced differential gene expression

Illumina BeadArray based gene expression profiling was carried out following low dose (75 nM and 100 nM) salinomycin treatment of MAF9 cells, the most sensitive primary mouse cell line examined (Supplementary Table S2). Overall output was characterized by plotting significance in the form of B-statistic (log-odds) or negative log10(Adjusted P-value) versus log2 expression (fold change) for each gene. Ultimately, only genes with −log10(Adjusted P-value) > 2 and log2(fold change) > 0.5 were considered (Figure 4A). All samples and transcripts induced or repressed at log2 (fold change) of 0.5 or more (P ≤ 0.05) were subjected to hierarchical agglomerative clustering by treatment with salinomycin (Figure 4B, left panel). Clustering was based on a Euclidean distance and complete linkage as distance and linkage methods. Transcripts induced or repressed at log2(fold change) of 0.5 or more (P ≤ 0.01) were sorted in ascending order by adjusted P-value. Twenty one probes, representing 18 genes, were identified for further evaluation (Figure 4B, right panel, Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 4. Differential gene expression in treated MAF9 cells.

A. Volcano plots of significance for each of 24,326 probes from salinomycin (75 nM and 100 nM) treated MAF9 cells in the form of B-statistic (log-odds) or negative log10 (Adjusted P-value) versus log2 (fold change) compared to 0.01% DMSO. Ultimately only genes with −log10 (Adjusted P-value) > 2 and log2 (fold change) > 0.5 were considered (marked by a red box). B. Hierarchical agglomerative clustered heatmaps of samples and transcripts induced or repressed at log2 (fold change) of 0.5 or more (P ≤ 0.05) (left panel) were sorted in ascending order (n=18 genes) by adjusted P-value to P ≤ 0.01 (right panel). Hierarchical clustering was based on a Euclidean distance and complete linkage as distance and linkage methods. C. Bar graph demonstrating validated expression of 17 of the 18 genes of interest as measured by real-time qRT-PCR. Mean relative expression (−ΔΔCT) values ± S.E.M of biological replicates (n=4) were plotted. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, t-test.

Col4a1 was excluded due to insufficient expression (CT > 35) and the remaining 17 genes were validated with high correlation (r2 = 0.901) to the array outputs for MAF9 (Supplementary Figure S4). All 17 genes were significantly differentially expressed (P < 0.05) in the MAF9 cells compared to control (Figure 4C) with lactotransferrin being the only gene with reduced expression following salinomycin treatment. qRT-PCR analysis of the salinomycin 17-gene signature was extended to A9M cells and over 50% (9/17) of the genes demonstrated differential expression to a significance level (P < 0.05).

The salinomycin 17-gene signature was further used to interrogate bioinformatic databases. Submission of the gene signature to GeneMania [19], a large association-based database, identified functional networks, including positive regulation of immune response and protein serine/threonine kinase activity, based primarily on co-expression with FDR values < 10−5 (Supplementary Figure S5). Submission of the translated 17-gene signature to the protein-protein interaction network STRING [20] identified three primary hubs (NF-kB, chemokine and DNA repair) centrally connected by Tnf, Mapk14 and Akt1 (Supplementary Figure S6A). Application of the signature to DAVID (The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) [21, 22] analysis identified the toll-like pathway (KEGG) with significance (P = 0.0063 corrected by the Benjamini-Hochberg method; Supplementary Figure S6B). Together, these analyses identified association of salinomycin treatment with primary immunomodulatory pathways.

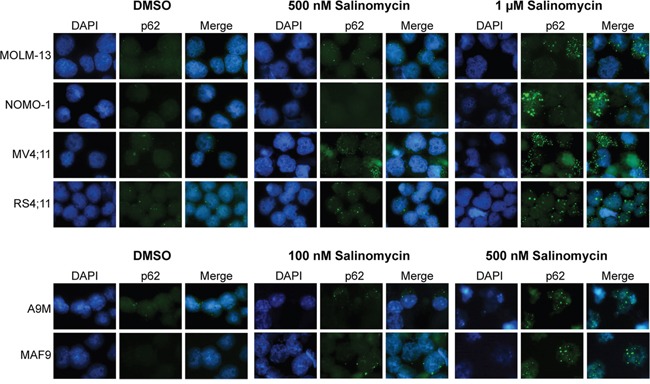

Induction of sequestosome-1(p62) positive aggresomes/vesicles

Five of the genes identified as part of the salinomycin-induced signature in MAF9 cells, including sequestosome-1 (Sqstm1/p62), were highly significantly upregulated (P < 0.001) compared to control (Supplementary Table S3). Sqstm1 is associated with the formation of polyubiquitin-containing aggresome-like induced structures (ALIS), which resemble the vesicles observed in the salinomycin-treated leukemic cell lines (Figures 1C, 2C and 3C). To examine this further, human MLLr and both primary cell lines were treated with salinomycin and probed for expression of Sqstm1/p62. Treated cells showed cytoplasmic restricted Sqstm1/p62 positivity, by co-immunofluorescence and DAPI staining, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). Quantitative scoring demonstrated a marked increase in the proportion of salinomycin treated Sqstm1/p62 positive cells compared to vehicle control (Supplementary Figure S7) associated with modest increased expression of Atg7 and Beclin-1, particularly in the more sensitive MAF9 cells, as determined by western blot analysis (Supplementary Figure S8). Together, these data indicate activation of an autophagic response by AML/MLLr cells to low-dose salinomycin treatment.

Figure 5. Induction of Sequestosome-1(p62) positive aggresomes/vesicles.

Combined immunofluorescence staining of SQSTM1/p62 with Alexa Fluor and DAPI depicting accumulation of cytoplasmic aggresomes/vesicles in MLLr, A9M and MAF9 cells treated with salinomycin for 48 hours at the indicated dosages or 0.01% DMSO. Representative images were taken using an x60 objective.

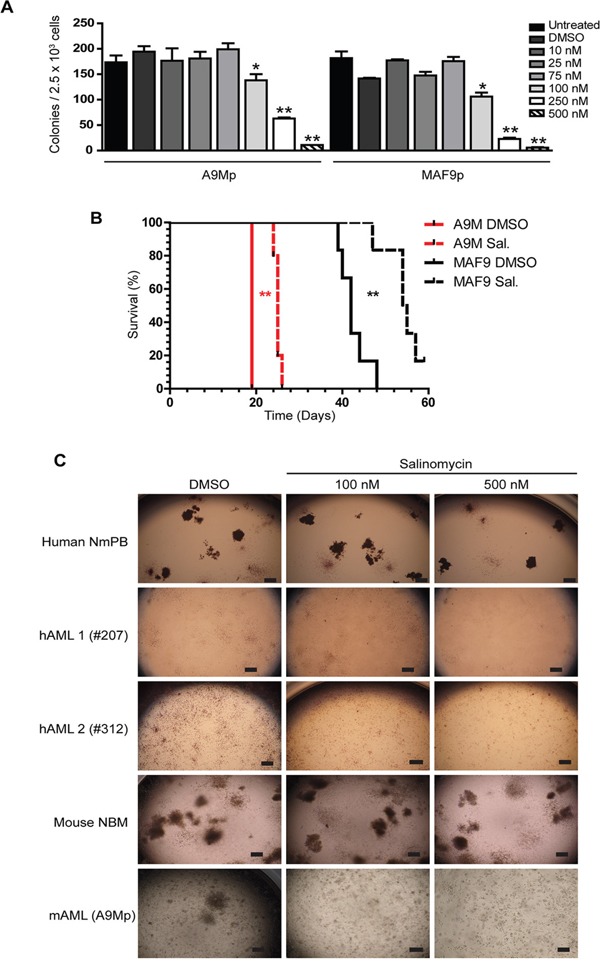

Anti-leukemic effects of salinomycin in primary cells

Primary mouse models and patient samples were next used to examine the anti-leukemic activity of salinomycin. Normal bone marrow (mouse) and donor derived mobilized peripheral blood (human) cells served as controls to examine potential toxicity to normal hematopoietic cells. As for the generated mouse cell lines, a range of low dose salinomycin (10 nM to 500 nM) was used to treat the corresponding primary leukemia cells (A9Mp and MAF9p, respectively). Myeloid colony formation for both primary leukemias was impaired in a dose dependent manner compared to controls (Figure 6A). To examine effects on leukemia maintenance, vehicle control or salinomycin treated primary leukemias were transplanted into recipient mice. Extension in survival was observed for both the early onset A9Mp (P = 0.0027) and late onset MAF9p cells (P = 0.002) treated with 500 nM salinomycin compared to controls (Figure 6B). The short extension in survival (~ 6 days) for the more aggressive A9M compared to the more sensitive MAF9 leukemias may reflect differences in cell of origin or repopulating cell numbers. Transplantation of salinomycin treated normal bone marrow cells had no deleterious effect on recipient mice within the time of evaluation (data not shown). Colony formation of mouse normal bone marrow (NBM) or normal mobilized peripheral blood (NMPB) was not markedly affected by salinomycin treatment (even at 500 nM), whereas the ability to form colonies was impaired by 100 nM and inhibited by 500 nM salinomycin treatment in both human (hAML1-3) and mouse (A9Mp, MAF9p) primary leukemias (Figure 6C). Interestingly, both mouse and patient derived leukemia cells appear to retain metabolic activity (as seen by incorporation of the INT stain) but the ability to form small clusters or colonies is impaired.

Figure 6. Anti-leukemic effects of salinomycin in primary cells.

A. Bar graphs showing decreased myeloid colony formation in untreated A9Mp and MAF9p primary mouse leukemia cells or following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage or 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. B. Kaplan Meier plots demonstrate extended survival in recipient mice (n=5 per group) following transplantation of salinomycin treated A9Mp or MAF9p primary leukemia cells compared to untreated or 0.01% DMSO vehicle controls. P-values, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test. C. Representative images of colony formation of human normal mobilized peripheral blood (NmPB), patient samples hAML-1(#207), hAML-2 (#312), mouse normal bone marrow (NBM) and mouse AML (A9Mp) following salinomycin treatment at the indicated dosage or 0.01% DMSO vehicle control. Colonies were stained with 1 mg/ml p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet for 16 hours and images captured at x2 using an inverted microscope. Scale bar = 4 μm.

DISCUSSION

Novel approaches to drug discovery for hematological malignancies are essential to take advantage of advances made in molecular classification over the last decade. Drug repurposing represents an attractive and economical option in which a novel application for an existing drug is indicated e.g. Metformin, the anti-type 2 diabetes mellitus drug, was recently found to have anti-neoplastic effects in several tissues including gynecological cancers [23]. Salinomycin is a polyether antibiotic with promising anti-cancer properties [7, 8, 12, 15], albeit at the micromole level with associated potential toxicities [24, 25]. A specific study on its potential clinical use in the acute leukemia context has not been reported.

Here, we investigated the anti-leukemic effects of low dose (sub-micromole) salinomycin in human and murine pre-clinical models, of AML and MLLr, including primary leukemia cells. Low dose salinomycin treatment resulted in reduced cell viability, increased apoptosis, vesicle formation and differentiation. A greater sensitivity was observed throughout for MLLr cells. The time and dose-dependent manner of the salinomycin effects indicated a biological response. Gene expression profiling and validation of the most sensitive murine MLLr cells revealed a salinomycin induced 17-gene signature, subsequently analyzed in the murine AML cells. Two of the genes verified in both primary cell lines, Klf6 and Ddit3, are markers of oxidative stress recently reported as upregulated by salinomycin in prostate cancer cells [26]. An additional gene identified, p62/Sqstm1, is required for aggresome formation linked to degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by autophagy [27]. Further analysis confirmed increased SQSTM1-positive aggresome formation and increased expression of Atg7 and Beclin-1 in salinomycin treated leukemic cells. Salinomycin has been reported to induce autophagy in other cancers [28–30]. However, whether this response is cancer cell protective or destructive requires further investigation. SQSTM1 was recently shown to shuttle polyubiquitinated proteins to nuclear promyelocytic leukemia bodies [31], and a specific role in this context may warrant further examination.

Submission of the gene signature to online bioinformatics databases identified several pathways and network hubs including: positive regulation of immune response and serine/threonine kinase activity (GeneMania); NF-kB, DNA-damage and chemokine hubs (STRING) and the Toll-like receptor pathway (DAVID). Together these analyses indicate activation of an immunomodulatory response by salinomycin treatment. Immunomodulation is well established as both a cellular and molecular therapy in hematological malignancies, including leukemia [32–34]. Specifically, activation of Toll-like receptor pathways promotes differentiation and growth inhibition in AML [35] and demonstrates efficacy in combination with anti-multiple myeloma agents including bortezomib, lenalidomide, melphalan or vorinostat [36]. Activation of an immune response may also reflect inherent inhibition of these pathways in MLLr and HOXA9-Meis-induced malignant cells, as recently reported for MN1 [37], and highlight a potential therapeutic role for salinomycin in these specific leukemias. The specific loss of colony formation of primary leukemia cells and associated loss of repopulating ability in vivo supports the reactivation of differentiation pathways by low dose salinomycin treatment. The fact that cells remain metabolically active yet incapable of forming colonies may also reflect subtle differences in mitochondrial and biosynthesis requirements for AML cells that are susceptible to antibiotics and can be exploited [37–42].

Indeed, association with chemotherapy [43] or combination with experimental therapies, including histone deacetylase inhibitors, in the form of anticancer kits that exploit cytotoxic and neo-protection [44], as recently reported for solid tumours [45, 46], may provide the best method to exploit the observed anti-leukemic effects of salinomycin.

Together, the data demonstrates efficacy of non-toxic low dose salinomycin treatment against poor prognostic MLLr and AML and provides insights into the underlying molecular mechanisms. Further investigation of the mechanism and in vivo use of low dose salinomycin as a monotherapy or in combination with either chemotherapy or epigenetic modifiers is warranted, to provide the basis for future clinical application.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human cell lines, murine primary cell lines and leukemias and patient samples

Established, well-characterized and authenticated (DSMZ-2015), mycoplasma free human AML (OCI-AML3, U937, HL60, NB4, and K562), t(9;11) MLLr (MOLM-13 and NOMO-1) and t(4;11) MLLr (MV4;11, and RS4;11) cell lines were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (RPMI-10; all Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Low passage numbers of ATCC or DSMZ-authenticated stocks were used throughout. Murine leukemia cell lines were generated by retroviral transduction of lineage depleted (Lin−; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) mouse primary bone marrow cells with MSCV-HOXA9-ires-Meis1 (A9M) and MSCV-MLL-AF9 (MAF9), following serial replating (x3) in MethoCult™ GF M3434 medium (Stem Cell Technologies). Single colonies were selected and expanded for each leukemia, and maintained in RPMI-10 supplemented with cytokine specific conditioned media (5 ng/ml mIL-3, 5 ng/ml mIL-6, 50 ng/ml mSCF and 5 ng/ml mGM-CSF; RPMI-10+) for over 2 months to become immortalized, as previously reported [47]. Cell lines generated were maintained at a density between 1-5×105 cells per ml and seeded every two to three days. Primary leukemias derived from the same retroviral vectors (A9Mp and MAF9p) were also maintained in vivo. In accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, patient samples and mobilized peripheral blood cells were collected, anonymized and analyzed following informed consent and ethical committee (OREC-NI) approval. Mononuclear cells purified using Ficoll-Paque™ (GE Healthcare BioSciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient centrifugation, were frozen and stored prior to treatment.

Animals, vectors and transplantation assays

Male and female congenic donor CD45.1+ (C57Bl6/Pep3b) or (C57Bl/6-Ly5.1) and recipient CD45.2+ (C57Bl/6J) mice (10-16 weeks old) were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility (BSU-QUB). Animal handling followed the guidelines of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Ethical Review Board (AWERB), Queen's University Belfast. Age-matched, randomized, animals were used throughout. Generation of vesicular stomatitis virus-pseudotyped retroviruses, infection of hematopoietic cells and transplantation into mice were performed as previously described [48].

Cell viability, cell cycle and morphology

Human and murine cell lines were treated for up to 72 hours in RPMI-10 or RPMI-10+ respectively containing either salinomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) at the stated concentration or 0.01% DMSO as vehicle control. Cell viability was determined by CellTiter-Glo® (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For cell cycle analysis, samples were fixed in 70% ethanol and DNA stained by Propidium Iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). DNA content was measured with an LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed using FACS DivaTM (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or Cyflogic software (CyFlo Ltd, Turku, Finland). Cells were pelleted, re-suspended in 200 μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS), cytospun (28 x g) for 5 minutes (Cytospin3, Thermo Shandon, Runcorn, UK) and stained with Modified Wright's stain, for morphology analysis.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol® (Life Technologies), and its quality was assessed using Agilent RNA 6000 Nano chip and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA integrity (RIN) values of >9 were obtained for all samples prior to application to the Mouse Ref-8 expression v.2 BeadArray (Illumina, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 550 ng of each RNA sample was reverse transcribed then in vitro transcribed to generate biotinylated cRNAs. Aliquots of labelled cRNAs (750 ng) were then hybridized to the BeadArray for 16-18 hours at 58°C. Signal detection was achieved using Amersham fluorolink streptavidin-Cy3 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK) and scanned images obtained using the Illumina BeadArray confocal scanner. Bead level data of biological triplicates were transformed to log2 scale, normalized (quantile method) using beadarray R package [49] and annotated (Gene Symbols, Names, Entrez IDs, and Probe Quality Grades) using illuminaMousev2.db R package [50]. Probes with poor quality grades were removed. Differential expression was then assessed by linear regression followed by parametric empirical Bayes analysis using limma R package [51] and output obtained by plotting significance versus log2 expression (fold change). Genes with expression ratios above log2(0.5)-fold between treatments and control (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) were identified. False discovery rates (FDR) were controlled using the Benjamini-Hochberg algorithm. Hierarchical clustering with complete linkage and Euclidean distance, as a measure of similarity, was performed.

qRT-PCR validation of beadarray data

Total RNA isolated from salinomycin or vehicle treated MAF9 and A9M cells was converted to cDNA [9]. Expression of 18 candidate genes with Peptidylprolyl isomerase A 1 (Ppia1) as endogenous control was quantified using technical duplicates of biological replicates (n=4). Genes and corresponding primers are listed (Supplementary Table S4). Assays were performed with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System using Sequence Detection System (SDS v2.3) software as per manufacturers’ protocols. Technical duplicates with standard deviations <0.6 CT were averaged, else a single value closest to other biological replicates was used.

Data were processed as reported previously [52]. Briefly, mean ΔCT values and standard errors calculated for each control and treatment group were normalized to yield −ΔΔCT (=ΔCTcontrol −ΔCTtreatment) values, which effectively constitute log2 fold changes in expression of genes of interest in treated samples compared to control.

Immunofluorescence

Treated and control cells were collected by centrifugation (107 x g), re-suspended in PBS, and 1 × 105 cells cytospun (28 x g) onto glass slides (Cytospin3, Thermo Shandon Ltd., Runcorn, UK). Cells were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 minutes, washed (x 2) in PBS, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 minutes, then incubated in 3% Bovine Serum Albumin Fraction V (BSA; Sigma Aldrich) for 30 minutes, all at room temperature. SQSTM1/p62 Alexa Fluor monoclonal antibody (Clone 864807; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) was diluted 1:10 in 3% BSA/PBS, as per the manufacturer's instructions, and slides were incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Following primary antibody labelling, slides were washed (x3) in PBS, air-dried, and mounting medium containing 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) applied prior to coverslip application. Slides were stored at 4°C prior to image capture using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope (x60 objective) (Nikon, Surrey, UK).

Salinomycin treatment of primary leukemias

Fresh primary murine leukemia or rapidly thawed primary AML patient bone marrow and mobilized peripheral blood samples were allowed to recover in RPMI-10+ or RPMI-10 respectively. Primary cells were treated with salinomycin or DMSO for 16 hours in liquid culture then plated in methylcellulose. Similarly treated human cells were seeded at 1 × 105/ml in MethoCult™ H4434 Classic (Stem Cell Technologies) and treated mouse leukemias were either seeded at 5 × 105/ml in MethoCult™ GF M3434 medium (Stem Cell Technologies) or directly transplanted (5 × 105 cells) into sub-lethally irradiated (850 cGy) recipient mice. Recipient mice were followed for up to 80 days, or disease endpoint, at which point necropsy was performed.

Methylcellulose assays, staining and imaging

Methylcellulose cultures were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 for up to 10 days when colony formation, colony counts, and images were captured and analyzed. Colony staining with 1 mg/ml p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (INT, Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) for 16 hours enabled visualization of colonies and metabolic activity.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software v5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Sample sizes of similar variance (n ≥ 3 for cell lines and n ≥ 5 for animal studies) were selected based on previous experience to provide sufficient statistical power. Means ± SEM were plotted and significance denoted by the value or as * p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001 throughout.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS METHODS FIGURES AND TABLES

Acknowledgments

The Authors gratefully acknowledge Pauline Erwin, Jill Killner and Hossein Essfandiary and Laura Smyth for technical support of the Illumina BeadArray, and staff within the Biological Services Unit, Bioinformatics, and Flow Cytometry Cores, Queen's University Belfast.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to the work described in this manuscript.

GRANT SUPPORT

CLB, GDRR, CD, JMR, and JMcK were funded by the Department of Employment and Learning NI. LMJK, NMM were supported by Bloodwise (UK). HLK, LMJK, KBM, IVG and KIM were supported by Leukaemia and Lymphoma NI. AT was supported by Bloodwise (UK) Grant Nos. 09035 and 07016 and Leukaemia and Lymphoma-NI grants R2055CNR and R2057CNR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, Sukhatme V, Sukhatme VP, Vikas P. The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) Project. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:442. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pammolli F, Magazzini L, Riccaboni M. The productivity crisis in pharmaceutical R&D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:428–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:40–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaitin KI, DiMasi Ja. Pharmaceutical innovation in the 21st century: new drug approvals in the first decade, 2000–2009. Clin Pharmacol Therapeutics. 2011;89:183–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893–907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vineis P, Wild CP. Global cancer patterns: causes and prevention. Lancet. 2014;383:549–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PB, Onder TT, Jiang G, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Weinberg RA, Lander ES. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell. 2009;138:645–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou S, Wang F, Wong ET, Fonkem E, Hsieh TC, Wu JM, Wu E. Salinomycin: a novel anti-cancer agent with known anti-coccidial activities. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:4095–101. doi: 10.2174/15672050113109990199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey JM, Kettyle LM, Sharpe DJ, Mulgrew NM, Dickson GJ, Bijl JJ, Austin P, Mayotte N, Cellot S, Lappin TR, Zhang SD, Mills KI, Krosl J, et al. Entinostat prevents leukemia maintenance in a collaborating oncogene-dependent model of cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1434–45. doi: 10.1002/stem.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitani M, Yamanishi T, Miyazaki Y. Salinomycin: a new monovalent cation ionophore. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;66:1231–1236. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitani M, Yamanishi T, Miyazaki Y, Otake N. Salinomycin effects on mitochondrial ion translocation and respiration. J Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9:655–660. doi: 10.1128/aac.9.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs D, Heinold A, Opelz G, Daniel V, Naujokat C. Salinomycin induces apoptosis, overcomes apoptosis resistance in human cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Chae M, Kim WK, Kim YJ, Kang HS, Kim HS, Yoon S. Salinomycin sensitizes cancer cells to the effects of doxorubicin and etoposide treatment by increasing DNA damage and reducing p21 protein. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:773–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim WK, Kim JH, Yoon K, Kim S, Ro J, Kang HS, Kim HS, Yoon S. Salinomycin, a p-glycoprotein inhibitor, sensitizes radiation-treated cancer cells by increasing DNA damage and inducing G2 arrest. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1311–1318. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu D, Choi MY, Yu J, Castro JE, Kipps TJ, Carson DA. Salinomycin inhibits Wnt signaling and selectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:13253–13257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110431108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novilla MN, Owen NV, Todd GC. The comparative toxicology of narasin in laboratory animals. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1994;36:318–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plumlee KH, Johnson B, Galey FD. Acute salinomycin toxicosis of pigs. Vet Diagn Invest. 1995;7:419–420. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Story P, Doube A. A case of human poisoning by salinomycin, an agricultural antibiotic. NZ Med J. 2004;117:U799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouious C, Kazi F, Lopes CT, Maitland A, Mostafavi S, Montojo J, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: Biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W214–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Siminovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, Kuhn M, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nature Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Febbraro T, Lengyel E, Romero I.L. Old drug, new trick: repurposing metformin for gynecologic cancers? Gynecolog oncol. 2014;135:614–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scherzed A, Hackenberg S, Froelich K, Rak K, Technau A, Radeloff A, Nöth U, Koehler C, Hagen R, Kleinsasser N. Effects of salinomycin on human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Toxicology Letters. 2013;218:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scherzad A, Hackenberg S, Schramm C, Froelich K, Ginzkey C, Hagen R, Kleinsasser N. Geno- and cytotoxicity of salinomycin in human nasal mucosa and peripheral blood lymphocytes. Toxicology in Vitro. 2015;29:813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ketola K, Hilvo M, Hyötyläinen T, Vuoristo A, Ruskeepää AL, Orešič M Kallioniemi O, Lljin K. Salinomycin inhibits prostate cancer growth and migration via induction of oxidative stress. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:99–106. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, Øvervatn A, Bjørkøy G, Jhansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jangamreddy JR, Ghavami S, Grabarek J, Kratz G, Wiechec E, Fredriksson BA, Rao Pariti RK, Cieślar-Pobuda, Panigrahi S, Łos MJ. Salinomycin induces activation of autophagy, mitophagy and affects mitochondrial polarity: differences between primary and cancer cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1833:2057–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jangamreddy JR, Panigrahi S, Łos MJ. Monitoring of autophagy is complicated-salinomycin as an example. Biochim et biophys acta. 2014;1853:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li T, Su L, Zhong N, Hao X, Zhong D, Singhal S, Liu X. Salinomycin induces cell death with autophagy through activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human cancer cells. Autophagy. 2013;9:1057–68. doi: 10.4161/auto.24632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pankiv S, Lamark T, Bruun JA, Øvervatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of p62/SQSTM1 and its role in recruitment of nuclear polyubiquitinated proteins to promyelocytic leukemia bodies. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5941–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.039925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rambaldi A, Biagi E, Bonini C, Biondi A, Introna M. Cell-based strategies to manage leukemia relapse: efficacy and feasibility of immunotherapy approaches. Leukemia. 2015;1:1–10. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersen MH. The targeting of immunosuppressive mechanisms in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2014;9:1784–92. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito Y, Nakahata S, Yamakawa N, Kaneda K, Ichihara E, Suekane A, Morishita K. CD52 as a molecular target for immunotherapy to treat acute myeloid leukemia with high EVI1 expression. Leukemia. 2011;6:921–31. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ignatz-Hoover JJ, Wang H, Moreton SA, Chakrabarti A, Agarwal MK, Sun K, Gupta K, Wald DN. The role of TLR8 signaling in acute myeloid leukemia differentiation. Leukemia. 2015;4:918–26. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ray A, Tian Z, Das DS, Coffman RL, Richardson P, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. A novel TLR-9 agonist C792 inhibits plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced myeloma cell growth and enhance cytotoxicity of bortezomib. Leukemia. 2014;28:1716–24. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma A, Yun H, Jyotsana N, Chaturvedi A, Schwarzer A, Yung E, Lai CK, Kuchenbauer F, Argiropoulos B, Görlich K, Ganser A, Humphries RK, Heuser M. Constitutive IRF8 expression inhibits AML by activation of repressed immune response signaling. Leukemia. 2015;1:157–68. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Lisanti CL, Tanowitz HB, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Targeting tumor-initiating cells: eliminating anabolic cancer stem cells with inhibitors of protein synthesis or by mimicking caloric restriction. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4569–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basak NP, Banerjee S. Mitochondrial dependency in progression of acute myeloid leukemia. Mitochondrion. 2015;21C:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skrtić M, Sriskanthadevan S, Jhas B, Gebbia M, Wang X, Wang Z, Hurren R, Jitkova Y, Gronda M, Maclean N, Lai CK, Eberand Y, Bartoszko J, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:674–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sriskanthadevan S, Jeyaraju DV, Chung TE, Prabha S, Xu W, Skrtic M, Jhas B, Hurren R, Gronda M, Wang X, Jitkova Y, Sukahai MA, Lin FH, et al. AML cells have low spare reserve capacity in their respiratory chain that renders them susceptible to oxidative metabolic stress. Blood. 2015;125:2120–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-594408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadowski MC, Pouwer RH, Gunter JH, Lubik AA, Quinn RJ, Nelson CC. The fatty acid synthase inhibitor triclosan: repurposing an anti-microbial agent for targeting prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:9362–81. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Liang C, Xue F, Chen W, Zhi X, Feng X, Bai X, Liang T. Salinomycin decreases doxorubicin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting the β-catenin/TCF complex association via FOXO3a activation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10350–65. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blagosklonny MV. A new science-business paradigm in anticancer drug development. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:103–6. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Booth L, Roberts JL, Conley A, Cruickshanks N, Ridder T, Grant S, Poklepovic A, Dent P. HDAC inhibitors enhance the lethality of low dose salinomycin in parental and stem-like GBM cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:305–16. doi: 10.4161/cbt.27309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kai M, Kanaya N, Wu SV, Mendez C, Nguyen D, Luu T, Chen S. Targeting breast cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast cancer using a combination of LBH589 and salinomycin. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151:281–94. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3376-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bach C, Buhl S, Mueller D, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Maethner E, Slany RK. Leukemogenic transformation by HOXA cluster genes. Blood. 2010;115:2910–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorsteinsdottir U, Mamo A, Kroon E, Jerome L, Bijl J, Lawrence HJ, Humphries RK, Sauvageau G. Overexpression of the myeloid leukemia-associated Hoxa9 gene in bone marrow cells induces stem cell expansion. Blood. 2002;99:121–129. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunning MJ, Smith ML, Ritchie ME, Tavaré S. beadarray: R classes and methods for Illumina bead-based data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2183–2184. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunning MJ, Lynch A, Eldridge M. illuminaMousev2.db: Illumina MouseWG6v2 annotation data (chip illuminaMousev2) R package version 1.24.0.

- 51.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.