Abstract

Background

Identifying factors linked to disordered eating in overweight and obesity (OV/OB) may provide a better understanding of youth at risk for disordered eating. This project examined whether ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction were associated with disordered eating.

Methods

ADHD symptoms, disordered eating, and body dissatisfaction were assessed in 220 youth ages 7–12 who were OV/OB.

Results

Multiple linear regressions showed that body dissatisfaction and ADHD symptoms were associated with disordered eating.

Discussion

Children with ADHD symptoms and OV/OB may be at greater risk for disordered eating when highly dissatisfied with their bodies. Healthcare providers should assess body image and disordered eating in youth with comorbid OV/OB and ADHD.

Keywords: Obesity, Children, Body Dissatisfaction, ADHD, Disordered Eating

Pediatric obesity has been identified as a major health concern in the United States with almost 1 in 3 youth considered overweight or obese (OV/OB) (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014). The adverse medical and psychosocial health correlates and sequelae of pediatric OV/OB are extensive (Daniels, 2006; Reilly & Kelly, 2011; Williams, Wake, Hesketh, Maher, & Waters, 2005). In recent years, externalizing psychological symptoms (e.g., attention problems, impulsivity) and disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have received increasing attention in relation to OV/OB due to the co-occurrence of these conditions and problematic associations with treatment outcomes (Cortese et al., 2008). The odds of being OV/OB are at least 1.5–2 times greater in children with ADHD (both medicated and non-medicated) than children without ADHD (Halfon, Larson, & Slusser, 2013; Waring & Lapane, 2008). Evidence suggests that ADHD medication (commonly stimulants) may influence this association, such that the likelihood of obesity in youth with ADHD who are not treated with medication is similar or higher to youth without ADHD (Byrd, Curtin, & Anderson, 2013). When considering the specific symptoms of ADHD, impulsivity has been demonstrated to share a distinct relationship with pediatric OV/OB through its role in excessive food consumption and displaced physical activity (Thamotharan, Lange, Zale, Huffhines, & Fields, 2013). In addition, inattentiveness has also been uniquely linked to children with obesity with suggested negative influence on attentiveness to hunger and satiety cues (Agranat-Meged et al., 2005; Davis, Levitan, Smith, Tweed, & Curtis, 2006). Furthermore, greater inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity in youth with obesity predicts poorer short- and long-term weight-related treatment outcomes (Nederkoorn, Braet, Van Eijs, Tanghe, & Jansen, 2006; van Egmond-Froehlich et al., 2012). Although the literature linking pediatric OV/OB and ADHD has grown, further investigation into the exact nature of the association and identification of contributing factors are still needed.

As disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (e.g., skipping meals, severe calorie restriction, excessive concern about shape and weight) have been linked to both pediatric OV/OB and ADHD (Biederman et al., 2007; Cortese & Vincenzi, 2012; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004), a small body of literature is emerging that examines disordered eating behaviors in relation to ADHD and weight status in youth. Authors of a recent population-based study conducted with Korean children (4.5% obese) reported that ADHD was associated with greater bulimic behaviors and consumption of unhealthy foods (Kim et al., 2014). The same study found that children with ADHD were more likely to have higher BMIs, although eating behaviors such as overeating and eating speed explained the association. Mixed results have emerged regarding bulimic and binge eating behaviors. Cortese and colleagues (2007) found a link between bulimic symptoms and ADHD symptoms in severely obese adolescents. In a pediatric sample, binge eating was related to ADHD after controlling for medication use (Reinblatt et al., 2014). However, Khalife and colleagues’ (2014) findings suggested that childhood ADHD symptoms at age 8 were not predictive of binge eating in adolescence (at age 16). Similarly, ADHD was not associated with any disordered eating behaviors including binge eating, dietary restraint, emotional eating, or external eating in youth who were OV/OB (Pauli-Pott, Becker, Albayrak, Hebebrand, & Pott, 2013). Despite the documented influence ADHD medication can have on weight and eating behaviors (Davis et al., 2012), there are few studies that report on ADHD medication use and how it relates to disordered eating and ADHD in youth with OV/OB. Overall, the findings regarding ADHD symptoms and disordered eating in youth who are OV/OB are mixed and often limited to particular types of disordered eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating, bulimic behaviors). Future investigation in this area warrants a more comprehensive examination of disordered eating and ADHD in the context of pediatric obesity, while accounting for other commonly identified factors associated with pediatric obesity (i.e., parent weight status, race/ethnicity, family income) (Carrière, 2003; Ogden et al., 2014), disordered eating (i.e., gender) (Croll, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Ireland, 2002), and ADHD (i.e., medication status) (Byrd et al., 2013). Further research is needed to elucidate whether there are associations between ADHD and specific types of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in youth with OV/OB in order to tailor treatment approaches appropriately.

As preliminary evidence is emerging that supports a link between disordered eating and ADHD in youth who are OV/OB, it may provide additional insight into youth who are at greater risk for developing disordered eating patterns to identify factors that increase the likelihood of disordered eating in this population. Body dissatisfaction has been documented in children as young as 5 years of age and is consistently identified as one of the strongest predictors of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (Davison, Markey, & Birch, 2003; Polivy & Herman, 2002). Moreover, increasing levels of body dissatisfaction have been associated with increasing weight status (Paxton, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2006). As such, the association between ADHD symptoms and disordered eating might be particularly likely among children with OV/OB who have high body dissatisfaction.

In addition to the psychological factors (i.e., body dissatisfaction, ADHD symptoms) that are of interest in relation to disordered eating attitudes and behaviors and obesity in youth, contextual factors are also of importance. Rurality is another factor that places children at increased risk for obesity and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Children who reside in rural areas of the U.S. are about 25% more likely to be OV/OB when compared to those living in metropolitan areas (Lutfiyya, Lipsky, Wisdom-Behounek, & Inpanbutr-Martinkus, 2007). Rurality is associated with increased poverty rates, medical comorbidities, and barriers to medical and mental health services (National Advisory Committee for Rural Health and Human Services, 2011). Individuals living in rural areas experience healthcare disparities and are often met with a number of barriers to healthcare including but not limited to financial difficulties, transportation/geographic constraints, limited providers and access to specialty care, and geographic limitations that may decrease likelihood for exercise and healthy eating (Goins, Williams, Carter, Spencer, & Solovieva, 2005). Recent evidence suggests that over two-thirds of rural children who are OV/OB engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors and almost one-fifth endorse clinically significant disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (Gowey, Lim, Clifford, & Janicke, 2014). This level of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors is slightly higher than the rates identified in a population-based study (Neumark-Sztainer, Story, Hannan, Perry, & Irving, 2002) and is associated with poorer health-related quality of life in rural children (Gowey et al., 2014). Rural youth with OV/OB warrant special attention due to their increased risk of medical and psychological comorbidities, decreased access to resources, and the potential negative impact these issues have on their quality of life and well-being.

The aims of this study are to (1) describe the prevalence of ADHD symptoms in a sample of youth with OV/OB living in a rural area, (2) determine whether ADHD symptoms are associated with disordered eating attitudes and behaviors after controlling for indicated variables (e.g., demographic factors, ADHD medication use), and (3) explore whether body dissatisfaction moderates the relation between ADHD symptoms and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in this sample of rural children with OV/OB. We hypothesized that the prevalence of ADHD symptoms would be consistent with previous studies (e.g., range between 12–25%) (Halfon et al., 2013; Marks, Shaikh, Hilty, & Cole, 2009) and that ADHD symptoms would be positively associated with total disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, as well as specific subtypes of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (Cortese, Bernardina, & Mouren, 2007; Reinblatt et al., 2014). In addition, we expected that body dissatisfaction would moderate the association, such that children with more ADHD symptoms and more body dissatisfaction would report more disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (Cortese & Vincenzi, 2012; Polivy & Herman, 2002) .

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Participants included 220 children, 7–12 years of age, with a BMI > 85th percentile for age and gender who were residing in a rural county in the Southeastern United States with their participating parent(s) or legal guardian(s). This study utilized pre-treatment data from a larger research project, the Extension Family Lifestyle Intervention Project (E-FLIP for Kids), which examined the effectiveness of year-long family-based weight management interventions for overweight and obese children. Parent and child dyads were recruited from rural communities using diverse methods, including direct mailings, brochure distributions through public schools and pediatrician offices, and community presentations (Janicke et al., 2011). Families completed an initial phone screening followed by an in-person screening to determine eligibility and to complete informed consent procedures. Eligible child and parent dyads completed pre-treatment child behavioral functioning, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors questionnaires, as well as height and weight measurements prior to randomization to one of three treatment arms (Janicke et al., 2011). The governing Institutional Review Board approved the larger study.

Measures

ADHD Symptoms

The Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorders (ADHD) Problems scale from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 2001) was used to assess difficulties with attention, hyperactivity, and skills/behaviors driven by executive functions. The CBCL is a commonly used parent rating scale that assesses both internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems in children 4–18 years of age (Achenbach, 2001). Extensive reliability and validity data have been reported on the CBCL, including excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability, a stable factor structure, and positive relations with other measures of childhood behavior (Dutra, Campbell, & Westen, 2004). The ADHD Problems scale consists of seven items (e.g., impulsive or acts without thinking, fails to finish things he/she starts) consistent with the diagnostic criteria of ADHD. Parents endorse each item on a 3-point Likert scale (Not True, Somewhat or Sometimes True, Very True or Often True). The ADHD Problems scale is considered a reliable and valid assessment of ADHD-related symptoms (Nakamura, Ebesutani, Bernstein, & Chorpita, 2009). In this sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the seven items on the ADHD Problems scale was .82, indicating good internal reliability. Derived from raw scores, T-scores were used in primary and secondary analyses with the following guidelines: 50 – 64 indicates typical functioning, 65 – 69 indicates borderline clinically impaired functioning, and ≥ 70 indicates clinically impaired functioning (Achenbach, 2001). The ADHD Problems scale was split into two scales for exploratory analyses, and the total sums of the raw scores of the four hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms and the three inattentive symptoms were utilized.

Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors

To assess disordered eating attitudes and behaviors children completed the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT) (Maloney, McGuire, & Daniels, 1988). The ChEAT is a 26-item self-report measure where items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 6 (Always). Scores are commonly recoded such that the three lowest scores (Never, Rarely, Sometimes) = 0, and more symptomatic scores are recoded with increasing values (Often = 1; Usually = 2; Always = 3). The measure results in a total score with possible scores ranging from 0–78 and four subscale scores: Dieting, Restricting and Purging, Food Preoccupation, and Oral Control (i.e., self-control of eating and pressure from others to eat) (Smolak & Levine, 1994). For the purposes of the current study the total score was used for the primary analysis and subscales were examined in secondary analyses. Clinically elevated disordered eating attitudes and behaviors are indicated by total scores of 20 or above (Maloney, McGuire, Daniels, & Specker, 1989). Previous research has demonstrated good internal reliability and concurrent validity with measures of body dissatisfaction and weight control behaviors (Smolak & Levine, 1994). The Cronbach’s alpha for the Total Scale in this sample was .80, indicating good internal reliability.

Body Dissatisfaction

The Children’s Body Image Scale (Truby & Paxton, 2002) is a self-report measure consisting of seven silhouettes of male or female children that correspond to increasing weight status. Children were asked to identify the body figure most like their own (perceived figure) and the body figure they would most like to have (ideal figure). In this sample, the items were significantly correlated (r = .34, p < .001). Body dissatisfaction was calculated by subtracting the number associated with the ideal figure from the number associated with the perceived figure. In this sample of children with OV/OB only one child had a negative score (−1) from rating their ideal figure as one size larger than their perceived figure.

Anthropometric Measurements

Measures of child height (to the nearest 0.1 cm) and weight (to the nearest 0.1 kg) were obtained by trained research personnel using a Harpendon stadiometer for height and a certified digital scale for weight. Children were dressed in light clothing and did not wear shoes for measurements. Child body mass index (BMI) z-score was calculated using age- and gender-specific norms published by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Kuczmarski et al., 2000).

Demographic Information

Parents completed a demographics questionnaire that included family background information, such as parent/child age, gender, race, marital status, education, occupation, family income, and prescribed child medication.

Data Analysis Plan

All measures had at least 80% completion rates to be scored and included in analyses. Descriptive statistics for the sample are represented by means, standard deviations, and percentages, including percent of children meeting at-risk and clinical cut-offs for ADHD symptoms (Aim 1). To identify covariates, Pearson correlational analyses were conducted between age, gender, child BMI z-score, parent BMI, family income, and variables of interest (total ChEAT score, body dissatisfaction, and ADHD symptoms), while ANOVAs were used to examine race/ethnicity differences and differences between children prescribed and not prescribed ADHD medications on the ChEAT. A multiple linear regression was conducted to evaluate the hypotheses that there is a positive association between ADHD symptoms and disordered eating (Aim 2). A moderation analysis was conducted using the SPSS macro PROCESS (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007), which conducts unstandardized hierarchical linear regressions and provides estimates of the effect of the independent variable at the values of the moderator variable, to evaluate the interaction between ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction on the outcome variable of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (Aim 3). The model was defined with ADHD symptoms as the independent variable, body dissatisfaction as the moderator variable, disordered eating attitudes and behaviors as the dependent variable, and identified covariates were included. Secondary analyses examined the relationship between ADHD symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and each of the four subscales of the ChEAT. Moderation models were used to test the effect of the interaction between ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction on the subscales of the ChEAT. Exploratory analyses examined relationships between hyperactive/impulsive symptoms or inattentive symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Two moderation models were used to test these associations and included hyperactive/impulsive symptoms and inattentive symptoms, in separate models, as the independent variables, body dissatisfaction as the moderator variable, disordered eating attitudes and behaviors as the dependent variable, and identified covariates in the model. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (21.0) for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Descriptive Information and Covariate Testing

A total of 220 youth with OV/OB, all part of a larger weight management intervention, were included in this study. Three participants were excluded from the initial sample of 223 due to missing data. Children were between the ages of 7–12 (M = 10.32, SD = 1.39) and 53.64% of the sample was female. The majority (90.45%) of the sample was obese. Child BMI z-scores ranged from 1.21–3.01 (M = 2.19, SD = .38), and BMI percentiles ranged from 88.76 to 99.86 (M = 97.92, SD = 2.08). The sample consisted of non-Hispanic white (64.09%), non-Hispanic African American (12.73%), non-Hispanic Asian/Asian-American (0.45%), non-Hispanic biracial (7.73%), Hispanic white (2.27%), Hispanic African-American (0.45%), and Hispanic biracial (4.55%) youth, in addition to those who did not disclose their ethnicity/race (7.73%). The median family income was in the $40,000-$59,999 range. Child self-report on the Children’s Body Image Scale and the ChEAT, along with parent-report of child ADHD symptoms on the CBCL are recorded in Table I. On the CBCL, there were a total of 11 children (5.00%) who scored in the clinical range (T-score ≥ 70) and 13 children (5.91%) who scored in the subclinical range (T-score 65–69) for ADHD symptoms. Parents reported that 13 children (5.91%) were prescribed medication specifically for ADHD. Of the children who were medicated, 4 (30.77%) scored in the subclinical or clinical range on the ADHD Problems scale, while the remaining 9 scored in the typical range. Clinically significant disordered eating attitudes and behaviors were endorsed on the ChEAT by 17.27% of the sample.

Table I.

Descriptive characteristics of key independent and dependent variables

| Measure | Mean | SD | Actual Min-Max |

Poss. Min-Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ChEAT | 11.91 | 9.10 | 0–53 | 0–69 |

| CBCL ADHD Problems | 55.44 | 6.75 | 50–80 | 50–80 |

| Children’s Body Image Scale | 2.78 | 1.31 | −1–6 | −6–6 |

ChEAT = Children’s Eating Attitudes Test; CBCL ADHD Problems = Child Behavior Checklist, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems scale

Table II shows correlation coefficients and significance for the continuous variables. Age and family income were significantly correlated with the total ChEAT score, while child BMI z-score and parent BMI were correlated with body dissatisfaction. Therefore, these variables were added to the models as covariates. There were no significant race/ethnicity differences with the total ChEAT score, ADHD symptoms, or body dissatisfaction (F(7, 212) = 1.00, p = .44; F(7, 212) = 0.46, p = .86; F(7, 212) = 0.92, p = .49, respectively). There were no ChEAT score differences between children prescribed ADHD medications and those not prescribed ADHD medications (F(1, 218) = 0.72, p = .40).

Table II.

Correlations among Age, Gender, BMI z-score, Family Income, Parent BMI and variables of interest (Total ChEAT and subscales, ADHD symptoms, and body dissatisfaction)

| Total ChEAT |

Diet | Restricting and Purging |

Food Preoccupati on |

Oral Control | CBCL ADHD Problems |

Body Dissatisf action |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.17* | −1.22 | −.07 | −.16* | −.12 | .03 | −.04 |

| BMI z- score |

.18 | .14* | .06 | .11 | −.07 | −.08 | .31* |

| Gender | .08 | .09 | .05 | .03 | −.01 | .05 | .07 |

| Family | −.17* | −.18* | −.12 | −.12 | −.04 | −.16* | −.08 |

| Income Parent BMI |

.01 | .00 | .01 | .10 | .01 | −.02 | .20* |

ChEAT = Children’s Eating Attitudes Test; CBCL ADHD Problems = Child Behavior Checklist, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems scale

p < .05

Primary analyses: Associations between ADHD symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors

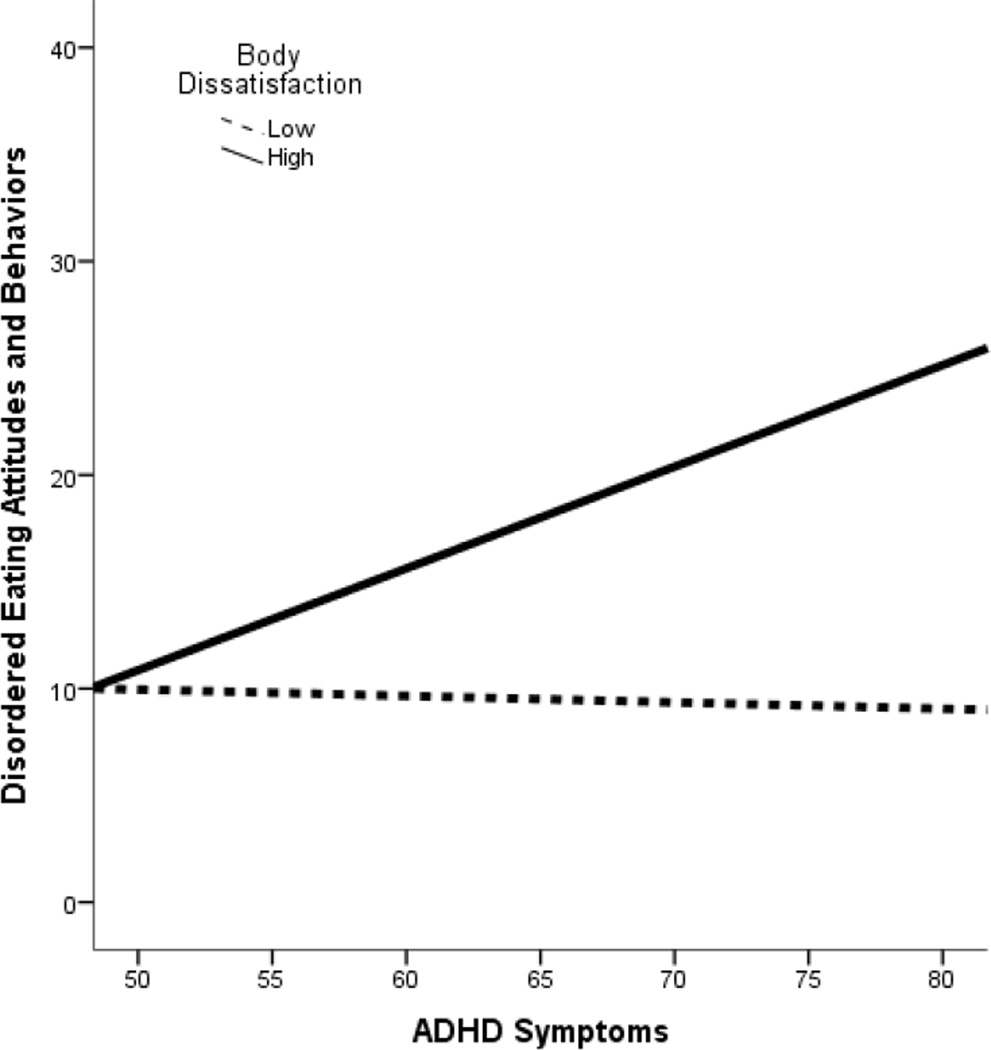

A linear relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating with age, family income, child BMI z-score, and parent BMI as covariates was significant (B = 1.50, t = 3.14, p < .01). A linear regression between ADHD symptoms and disordered eating with the same covariates was also significant (B = .28, t = 3.11, p < .01). The moderation model, with age, family income, child BMI z-score, and parent BMI as covariates, showed that the interaction between ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction was statistically significant (B = .16, t = 2.52, p = .01; see Figure I and Table III). The overall moderation model was statistically significant (p < .001) and explained 16.26% of the variance in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. The r-squared increase due to the interaction in the model was 2.51%. This interaction was also significant in the model without covariates (B = .15, t = 2.43, p < .05). Due to the interaction’s significance, the relationship between ADHD symptoms and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors was further explored using post-hoc probing to analyze the conditional effect of ADHD symptoms on disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. A statistically significant effect in the model appeared at a body dissatisfaction rating of 2.29 (p = .05) and continued to show even greater significance at higher ratings of body dissatisfaction. Thus, when children’s ideal body figure was more than two sizes smaller than their perceived body figure (i.e., children were more dissatisfied with their bodies) there was a significant relationship between level of ADHD symptoms and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors.

Figure I.

Interaction between ADHD Symptoms and Body Dissatisfaction in Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors Outcomes

*Low body dissatisfaction is defined by scores below 2.29 and high body dissatisfaction is defined by scores above 2.29

*Body dissatisfaction scores are derived from the Children’s Body Image Scale

Table III.

Moderation Model Predicting Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors (Total ChEAT)

| B | SE | P | R2 | p | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Model | .16 | <.001 | 5.88 | |||

| Constant | 28.97 | 11.95 | .02 | |||

| Interaction (Body dissatisfaction and ADHD sxs) |

.16 | .06 | .01 | |||

| Body Dissatisfaction | −7.60 | 3.56 | .03 | |||

| ADHD symptoms | −.19 | .19 | .32 | |||

| Child Age | −1.00 | .41 | .02 | |||

| Family Income | −.74 | .40 | .07 | |||

| Child BMI z-score | 2.32 | 1.66 | .16 | |||

| Parent BMI | −.07 | .07 | .33 |

ChEAT = Children’s Eating Attitudes Test

Secondary analyses: Associations between ADHD symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and subtypes of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors

Additional moderation analyses were conducted to examine associations between child ADHD symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and specific types of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors on the ChEAT (i.e., ChEAT subscales). To identify covariates, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and BMI z-score, Pearson correlational analyses were conducted between continuous variables (See Table II) and ANOVAs were used for the categorical variable, race/ethnicity. Those demographic variables that were significantly related to a specific CHEAT subscale were then added to the corresponding moderation models as a covariate. Moderation analyses revealed that there was a significant interaction between ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction for Food Preoccupation (B = .05, t = 3.07, p < .01) and Oral Control (B = .03, t = 3.22, p < .01). The interaction was not significantly associated with the Dieting (B = .06, t = 1.45, p = .149) or Restricting and Purging (B = .02, t = .75, p = .46).

Exploratory analyses: Associations between hyperactive/impulsive or inattentive symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors

To further explore the interaction between ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction on disordered eating, the ADHD symptom subscale from the CBCL was split into hyperactive/impulsive symptoms and inattentive symptoms. Age, family income, child BMI z-score, and parent BMI were included as covariates in the moderation models. The model examining the interaction between inattentive symptoms and body dissatisfaction accounted for 17.25% of the variance in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (B = .69, t = 2.38, p = .01). The overall model examining the interaction between hyperactive/impulsive symptoms and body dissatisfaction explained 13.35% of the variance in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (B = .43, t = 1.98, p < .05).

The moderation models that were significant in secondary analyses examining subscales of the ChEAT were also examined in association with hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive symptoms, and included covariates. Hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were significantly associated with Food Preoccupation (B = .15, t = 3.06, p < .01) and Oral Control (B = .08, t = 2.50, p = .01). Inattentive symptoms were also associated with both scales of Food Preoccupation (B = .21, t = 3.17, p < .01) and Oral Control (B = .12, t = 2.93, p < .01).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the associations between ADHD symptoms, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in a sample of rural youth with OV/OB. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that body dissatisfaction moderates the relationship between ADHD and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in children who are OV/OB. These results suggest that children with OV/OB who exhibit greater levels of ADHD symptoms and are highly dissatisfied with their bodies may be at greater risk for engaging in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. This study also extends the relationship between ADHD and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in youth to an overweight, rural sample. These findings are consistent with our predictions based on the existing literature and may help begin to understand and identify children with co-occurring ADHD and obesity who may be engaging in or at risk for disordered eating attitudes and behaviors.

The interaction between ADHD symptoms and body dissatisfaction suggests that children with OV/OB who experience a high level of body dissatisfaction and exhibit ADHD symptoms are at greater risk for disordered eating attitudes and behaviors than those with a low level of body dissatisfaction. As the majority of the sample endorsed some level of body dissatisfaction, which is common in children with obesity (Harriger & Thompson, 2012), these results suggest that the presence of high body dissatisfaction placed children with ADHD symptoms and OV/OB at even greater risk for engaging in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Perhaps one explanation could be due to the core characteristics of ADHD symptoms, including difficulties with attention and impulsivity. Exploratory results suggest that symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity were related to disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in children with high body dissatisfaction. This is consistent with past findings that linked inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity to disordered in youth with OV/OB (Braet, Claus, Verbeken, & Van Vlierberghe, 2007; Nederkoorn et al., 2006) and provides insight into factors (i.e., body dissatisfaction) that may exacerbate this association. It is possible that children with difficulties in inhibition and/or self-regulation of behavior and emotion may be more likely to have difficulties inhibiting urges to engage in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in response to negative cognitions and emotions related to their body dissatisfaction.

The parent-reported rate of clinical and subclinical levels of ADHD symptoms identified by the CBCL in the current sample of rural youth with OV/OB was approximately 10% when combined. This is similar to the 12% prevalence rate of comorbid pediatric ADHD and OV/OB in a population-based study of 10–17 year-olds (Halfon et al., 2013) and extends those findings to children as young as 7 years of age. However, the rate of co-occurring ADHD and OV/OB in the current sample is lower than some of the rates identified by past research. One specific study found that 25% of rural youth (ages 21 and younger) with OV/OB presenting for consultation to a telepsychiatry clinic had an ADHD diagnosis (Marks et al., 2009). The discrepancy between the rates of comorbid ADHD and OV/OB in the rural youth in the current study and those previously identified (Marks et al., 2009) could be due to the variability in measurement tools used among these studies (e.g., parent-report vs. retrospective medical record review). Another potential explanation may be that Marks and colleagues’ (2009) sample included a much broader age range of individuals who were presenting for psychiatric consultation and, thus, were more likely to be experiencing psychological symptoms including ADHD symptoms. More research is needed to identify the proportion and characteristics of youth with OV/OB living in rural areas who also experience comorbid mental health conditions in order to appropriately identify and tailor intervention methods.

Children who are OV/OB with ADHD symptoms and high body dissatisfaction endorsed greater levels of Food Preoccupation and Oral Control on the ChEAT than those with low body dissatisfaction, although no differences were found in Dieting or Restricting and Purging. These findings are partially consistent with the findings of Pauli-Pott et al. (2013) who did not identify any associations between ADHD and dietary restraint in youth with OV/OB, or any other type of disordered eating. This may be due to the unique characteristics of the study sample, specifically their ADHD symptoms, as past research more commonly shows links between ADHD and binge and bulimic behaviors rather than restrictive or dieting behaviors in children (Bleck & DeBate, 2013; Cortese, Bernardina, et al., 2007). As such, the findings that hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention were uniquely associated with Food Preoccupation and Oral Control in the current sample of OV/OB youth are similar to those of Reinblatt and colleagues (2014) who identified a link between ADHD and binge eating in youth with severe obesity. Taken together, these findings suggest that specific types of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors may manifest in this population, such as thinking about food too much and feeling pressured by others about their eating habits. The current results provide support for past research that identified dysregulated eating patterns of children with ADHD and obesity, in which children with ADHD were described as more impulsive as they ate faster at the beginning of meals, whereas children with OV/OB appeared to be inattentive as they ate rapidly throughout the meal (Wilhelm et al., 2011). Children who exhibit impulsivity may have a difficult time inhibiting their desire to eating highly palatable foods when they are present (Van den Berg et al., 2011). However, inattention may also impact eating behaviors by decreasing awareness of the type or amount of food consumed and internal cues of satiety (Davis et al., 2006). Another potential explanation for these findings may be that children with attention problems may eat in an effort to focus their attention, which could be an interesting area for future research in children with obesity and ADHD. Further research is needed to support these findings in youth with concurrent ADHD and OV/OB to examine the underlying processes that are associated with different types of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Executive functioning is one domain of interest for further exploration, as deficits in these processes are strongly related to ADHD (Willcutt, Doyle, Nigg, Faraone, & Pennington, 2005) and have also been linked to various types of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors across weight conditions (Fagundo et al., 2012; Lena, Fiocco, & Leyenaar, 2004). In fact, recent research suggests that impairments in executive functions, specifically self-regulation of behavior and emotion, may help explain the link between pediatric obesity and ADHD (Graziano et al., 2012). Executive dysfunction such as decreased inhibitory control, attention, mental flexibility, and working memory have been identified in relation to pediatric OV/OB (Reinert, Po’e, & Barkin, 2013). Furthermore, a pediatric obesity intervention targeting working memory and inhibition showed positive improvements in executive functioning and ability to maintain weight loss at follow-up (Verbeken, Braet, Goossens, & van der Oord, 2013). Further research on executive functioning as a mechanism of pediatric OV/OB and disordered eating is warranted.

The results of the present study should be considered in the context of several limitations. The cross-sectional nature of this study limits the ability to draw conclusions about the directional nature of these relationships. Future longitudinal research should focus on identifying the temporal relationship among obesity, ADHD, body image concerns, and disordered eating patterns in order to provide a better understanding of the development of these relationships and risk factors, as well as critical intervention periods. In the current study, ADHD symptoms were assessed using parent-report of child symptoms, although previous research has demonstrated the incremental utility of multi-informant reporters for the positive diagnosis of ADHD (Power et al., 1998). In addition, exploratory results should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of psychometrics for examining the ADHD Problems scale into separate symptom subscales of hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention. While the percentage of children that represented subclinical or clinical levels of ADHD and disordered eating were similar to other studies, the number of children that comprised these groups was relatively small. In addition, as the population of interest was rural children with OV/OB, the generalizability of results to children who are not OV/OB and those from non-rural areas is limited. Additional research on youth with OV/OB in urban environments may help to clarify whether these concerns may be specific to rural children and extend to or perhaps become even more salient in adolescence, a period of heightened risk for disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (Smink, Hoeken, & Hoek, 2012). In addition, research examining these constructs with children who are not OV/OB would also be important.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The current study demonstrates a link between ADHD symptoms and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in children who are OV/OB. Furthermore, these findings extend our understanding of this relationship by identifying the increased risk that body dissatisfaction poses on children with ADHD symptoms and obesity. The current study findings underscore the importance of assessment and integration of disordered eating and body image psychoeducation and treatment components into pediatric obesity interventions (Kelly, Bulik, & Mazzeo, 2011; Stice, Rohde, Shaw, & Marti, 2013; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2014). Body image may need to be more commonly assessed in pediatric specialty clinics (e.g., obesity or mental health clinics) where children with comorbid ADHD and OV/OB are more likely to present (Vander Wal & Mitchell, 2011). Body image can be assessed using brief single or double item questionnaires, such as the measure used in the current study (Truby & Paxton, 2002), and may yield important information about a child’s risk for further eating problems to inform prevention and intervention efforts. In addition to appropriate screening protocols for specialty obesity or mental health clinics where children with comorbid OV/OB and ADHD who may also be at risk for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors may be most likely to present (Lutfiyya et al., 2007), further development of comprehensive interventions for addressing obesity and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors including body dissatisfaction are warranted for this population. In particular, it will be important to consider screening for and targeting underlying symptomatology such as impulsivity, attention problems, and other potential executive dysfunction utilizing novel approaches that collectively address disordered eating, obesity, and ADHD (Juarascio, Manasse, Espel, Kerrigan, & Forman, 2015; Verbeken et al., 2013).

Providers and parents of children with comorbid ADHD and obesity should familiarize themselves with the types of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors that may be more likely to manifest in their patients and children, as well as resources appropriate for addressing those concerns in order to appropriately identify and intervene if necessary. Importantly, children and families living in underserved areas such as those in the current study often have limited access to mental health resources despite increased rates of obesity, medical and psychological problems, and disordered eating (Gowey et al., 2014; Lutfiyya et al., 2007). E-health interventions may be an invaluable and cost-effective resource for further exploration in helping to educate, screen, and treat these difficulties in underserved and rural populations.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Agranat-Meged AN, Deitcher C, Goldzweig G, Leibenson L, Stein M, Galili-Weisstub E. Childhood obesity and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a newly described comorbidity in obese hospitalized children. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(4):357–359. doi: 10.1002/eat.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Ball SW, Monuteaux MC, Surman CB, Johnson JL, Zeitlin S. Are Girls with ADHD at Risk for Eating Disorders? Results from a Controlled, Five-Year Prospective Study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(4):302–307. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3180327917. 310.1097/DBP.1090b1013e3180327917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleck J, DeBate RD. Exploring the co-morbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors in a nationally representative community-based sample. Eating Behaviors. 2013;14(3):390–393. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.009. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet C, Claus L, Verbeken S, Van Vlierberghe L. Impulsivity in overweight children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(8):473–483. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd HCM, Curtin C, Anderson SE. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obesity in US males and females, age 8–15 years: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Pediatric Obesity. 2013;8(6):445–453. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrière G. Parent and child factors associated with youth obesity. Health reports. 2003;14(Suppl):29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Angriman M, Maffeis C, Isnard P, Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Mouren MC. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obesity: a systematic review of the literature. [Review] Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008;48(6):524–537. doi: 10.1080/10408390701540124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Bernardina BD, Mouren MC. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and binge eating. [Review] Nutr Rev. 2007;65(9):404–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Isnard P, Frelut ML, Michel G, Quantin L, Guedeney A, Mouren MC. Association between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bulimic behaviors in a clinical sample of severely obese adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(2):340–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Vincenzi B. Obesity and ADHD: Clinical and Neurobiological Implications. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;9:199–218. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(2):166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. The future of children. 2006;16(1):47–67. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Fattore L, Kaplan AS, Carter JC, Levitan RD, Kennedy JL. The suppression of appetite and food consumption by methylphenidate: The moderating effects of gender and weight status in healthy adults. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;15(2):181–187. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Levitan RD, Smith M, Tweed S, Curtis C. Associations among overeating, overweight, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A structural equation modelling approach. Eating Behaviors. 2006;7(3):266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.09.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Markey CN, Birch LL. A longitudinal examination of patterns in girls’ weight concerns and body dissatisfaction from ages 5 to 9 years. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33(3):320–332. doi: 10.1002/eat.10142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Campbell L, Westen D. Quantifying clinical judgment in the assessment of adolescent psychopathology: reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Child Behavior Checklist for clinician report. Journal of clinical psychology. 2004;60(1):65–85. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundo AB, De la Torre R, Jiménez-Murcia S, Agüera Z, Granero R, Tárrega S, Rodríguez R. Executive functions profile in extreme eating/weight conditions: from anorexia nervosa to obesity. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, Spencer M, Solovieva T. Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: a qualitative study. J Rural Health. 2005;21(3):206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowey MA, Lim CS, Clifford LM, Janicke DM. Disordered Eating and Health-Related Quality of Life in Overweight and Obese Children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Bagner DM, Waxmonsky JG, Reid A, McNamara JP, Geffken GR. Co-occurring weight problems among children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The role of executive functioning. International Journal of Obesity (Lond) 2012;36(4):567–572. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N, Larson K, Slusser W. Associations between obesity and comorbid mental health, developmental, and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample of US children aged 10 to 17. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriger JA, Thompson JK. Psychological consequences of obesity: Weight bias and body image in overweight and obese youth. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24(3):247–253. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.678817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicke DM, Lim CS, Perri MG, Bobroff LB, Mathews AE, Brumback BA, Silverstein JH. The Extension Family Lifestyle Intervention Project (E-FLIP for Kids): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarascio AS, Manasse SM, Espel HM, Kerrigan SG, Forman EM. Could training executive function improve treatment outcomes for eating disorders? Appetite. 2015;90:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly N, Bulik C, Mazzeo S. An exploration of body dissatisfaction and perceptions of Black and White girls enrolled in an intervention for overweight children. Body Image. 2011;8(4):379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalife N, Kantomaa M, Glover V, Tammelin T, Laitinen J, Ebeling H, Rodriguez A. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are risk factors for obesity and physical inactivity in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Kwon HJ, Ha M, Lim MH, Oh SY, Kim JH, Paik KC. Relationship among attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, dietary behaviours and obesity. Child Care Health Dev. 2014 doi: 10.1111/cch.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Johnson CL. CDC growth charts: United States. Advance Data. 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena SM, Fiocco AJ, Leyenaar JK. The role of cognitive deficits in the development of eating disorders. Neuropsychology Review. 2004;14(2):99–113. doi: 10.1023/b:nerv.0000028081.40907.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfiyya MN, Lipsky MS, Wisdom-Behounek J, Inpanbutr-Martinkus M. Is rural residency a risk factor for overweight and obesity for U.S. children? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(9):2348–2356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney MJ, McGuire J, Daniels SR, Specker B. Dieting behavior and eating attitudes in children. Pediatrics. 1989;84(3):482–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney MJ, McGuire JB, Daniels SR. Reliability testing of a children’s version of the Eating Attitude Test. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27(5):541–543. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks S, Shaikh U, Hilty DM, Cole S. Weight status of children and adolescents in a telepsychiatry clinic. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Telemed J E Health. 2009;15(10):970–974. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Ebesutani C, Bernstein A, Chorpita BF. A psychometric analysis of the child behavior checklist DSM-oriented scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31(3):178–189. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9174-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Committee for Rural Health and Human Services. Report to the secretary: Rural Health and human services issues. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Braet C, Van Eijs Y, Tanghe A, Jansen A. Why obese children cannot resist food: The role of impulsivity. Eating Behaviors. 2006;7(4):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.11.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Irving LM. Weight-related concerns and behaviors among overweight and nonoverweight adolescents: Implications for preventing weight-related disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(2):171–178. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli-Pott U, Becker K, Albayrak O, Hebebrand J, Pott W. Links between psychopathological symptoms and disordered eating behaviors in overweight/obese youths. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(2):156–163. doi: 10.1002/eat.22055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys: A five-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):888–899. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman CP. Causes of eating disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53(1):187–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Andrews TJ, Eiraldi RB, Doherty BJ, Ikeda MJ, DuPaul GJ, Landau S. Evaluating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder using multiple informants: The incremental utility of combining teacher with parent reports. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(3):250. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hyptheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly J, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(7):891–898. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinblatt SP, Leoutsakos JM, Mahone EM, Forrester S, Wilcox HC, Riddle MA. Association between binge eating and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in two pediatric community mental health clinics. Int J Eat Disord. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eat.22342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert KR, Po’e EK, Barkin SL. The relationship between executive function and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Journal of obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/820956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smink FE, Hoeken D, Hoek H. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(4):406–414. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L, Levine MP. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(3):275–282. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199411)16:3<275::aid-eat2260160308>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H, Marti CN. Efficacy trial of a selective prevention program targeting both eating disorders and obesity among female college students: 1-and 2-year follow-up effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(1):183. doi: 10.1037/a0031235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, Radin RM. Targeted prevention of excess weight gain and eating disorders in high-risk adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2014;100(4):1010–1018. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.092536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamotharan S, Lange K, Zale EL, Huffhines L, Fields S. The role of impulsivity in pediatric obesity and weight status: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(2):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.12.001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truby H, Paxton SJ. Development of the children’s body image scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41(2):185–203. doi: 10.1348/014466502163967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg L, Pieterse K, Malik J, Luman M, van Dijk KW, Oosterlaan J, Delemarre-van de Waal H. Association between impulsivity, reward responsiveness and body mass index in children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(10):1301–1307. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Egmond-Froehlich A, Bullinger M, Holl RW, Hoffmeister U, Mann R, Goldapp C, de Zwaan M. The hyperactivity/inattention subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire predicts short- and long-term weight loss in overweight children and adolescents treated as outpatients. [Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Obes Facts. 2012;5(6):856–868. doi: 10.1159/000346138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Wal JS, Mitchell ER. Psychological complications of pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(6):1393–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeken S, Braet C, Goossens L, van der Oord S. Executive function training with game elements for obese children: a novel treatment to enhance self-regulatory abilities for weight-control. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(6):290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring ME, Lapane KL. Overweight in children and adolescents in relation to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a national sample. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e1–e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm C, Marx I, Konrad K, Willmes K, Holtkamp K, Vloet T, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Differential patterns of disordered eating in subjects with ADHD and overweight. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(Suppl 1):118–123. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.602225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the Executive Function Theory of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1336–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Wake M, Hesketh K, Maher E, Waters E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. JAMA. 2005;293(1):70–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]