Abstract

Despite increasing recognition of the role nutrition plays in the health of current and future generations, many women struggle to eat healthy. We used the PhotoVoice method to engage 10 rural women in identifying perceived barriers and facilitators to healthy eating in their homes and community. They took 354 photographs, selected and wrote captions for 62 images, and explored influential factors through group conversation. Using field notes and participant-generated captions, the research team categorized images into factors at the individual, relational, community/organizational, and societal levels of a socioecological model. Barriers included limited time, exposure to marketing, and the high cost of food. Facilitators included preparing food in advance and support from non-partners; opportunities to hunt, forage, and garden were also facilitators, which may be amplified in this rural environment. Nutritional interventions for rural women of childbearing age should be multi-component and focus on removing barriers at multiple socioecological levels.

Keywords: research, rural; women’s health; maternal behavior; diet, nutrition, malnutrition; community capacity and development; participatory action research (PAR); PhotoVoice

Introduction

Maternal nutrition before and during pregnancy is critically important to the health of the mother as well as to her offspring as a child and future adult. The primary example of this association was first suspected in the late 1960s, when investigators identified the relationship between a mother’s folic acid intake and the development of spina bifida in her offspring (Crider, Bailey, & Berry, 2011). Subsequent research has found that inadequate nutrition prior to and after conception contributes to structural and epigenetic changes that predispose the developing fetus to higher lifetime risks of obesity, schizophrenia, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (Barger, 2010; Barker, 1997; de Boo & Harding, 2006; Finney-Brown, 2011). Poor growth associated with dietary intake in early life can also lead to compromised cognitive function in later life (Black, 2003; Morley & Lucas, 1997).

This growing body of evidence suggests that a portion of the high prevalence of chronic disease has roots in events that are occurring in the womb, long before societal influences and lifestyle choices come into play for the affected adults (Wu, Bazer, Cudd, Meininger, & Spencer, 2004). New modes of health promotion and disease prevention are needed to move interventions “upstream,” shifting from attempts to modify adult health behaviors solely for the benefit of the current generation to interventions that also reduce biological disadvantage in future generations. Researchers and service providers who hope to develop and implement these interventions could benefit from understanding what women perceive as factors that influence their nutritional behaviors.

We used PhotoVoice, a participatory action research method, to explore how context shapes nutritional behaviors for women of childbearing age in one rural county along the Oregon coast. Our aim was to identify environmental, behavioral, and cultural factors that act as barriers or facilitators to healthy eating for these women. The PhotoVoice method generates rich qualitative data in the form of images and narratives that can inform research as well as be used to mobilize community-level change.

Method

Design

For this community-engaged research project, we used a modified PhotoVoice process as a participatory method of community assessment and asset mapping (Findholt, Michael, & Davis, 2011; Wang & Burris, 1997). The PhotoVoice method uses documentary photography and critical dialogue to examine the factors that shape complex behaviors by viewing the world through the eyes of the participants (Wang, 2003). PhotoVoice has been found to empower participants to advocate for change while identifying community assets and needs (Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Duffy, 2011; Morgan et al., 2010). The method has been used successfully in studying nutrition in various contexts (e.g., Lardeau, Healey, & Ford, 2011; Martin, Garcia, & Leipert, 2010), but to our knowledge not with rural women of childbearing age. The study protocol was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Institutional Review Board (#10815).

Setting and Project Partners

This study took place in a rural, coastal county of Oregon, which has a population of 37,400 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). The main employers in the county are pulp and paper mills, two hospitals, government agencies, the Coast Guard, and the seasonally dependent hospitality industry (Community Assessment, 2013). Table 1 provides a summary of population characteristics for this county, and for the state of Oregon.

Table 1.

Community and Population Characteristics of the Participating Rural County Compared With Oregon.

| Characteristic | Rural County | Oregon |

|---|---|---|

| Population (2014 estimate) | 37,474 | 3,970,239 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White alone, percent, 2013 | 93.5 | 88.1 |

| Hispanic or Latino, percent, 2013 | 8 | 12.3 |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate or higher (persons age 25+, 2009–2013) | 91.5% | 89.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher (persons age 25+, 2009–2013) | 23.2% | 29.7% |

| Median household income, 2009–2013 | $44,683 | $50,229 |

| Persons per square mile, 2010 | 44.7 | 39.9 |

Source. U.S. Census Bureau (2015).

This study was conducted in partnership with an established community-based health and wellness coalition, the Community Health Advocacy and Resource Team (CHART). CHART includes representatives from health and social service agencies as well as city and county government organizations. Its mission is to improve the health of county residents by working with community members collaboratively to achieve policy, systems, and environmental change (CHART, 2015). Our research team met with CHART to align project goals and timing prior to initiating this study. We identified a member of CHART to serve as the study’s community liaison and developed a PhotoVoice study sub-committee. CHART members supported project activities by helping with participant recruitment, data interpretation, and dissemination of study findings.

Participants

Women of childbearing age (18 to 50 years old) living in the county for the last 12 months or longer were eligible to participate. CHART members posted recruitment flyers in their places of business and discussed the opportunity with their clientele. Interested women completed a five-page participant interest form (available in both English and Spanish), which included demographic questions (e.g., employment, income, children, education, access to health care), a statement of commitment to attend at least four PhotoVoice meetings (three work sessions and one presentation), and a willingness to participate in the study activities (e.g., taking photos, writing captions, discussing images in a group setting). Copies of the participant interest form are available in Online Supplement 1.

Thirteen women submitted applications to participate in the study. Research team members contacted interested applicants by phone and email to confirm participant eligibility and review a series of intake interview questions to assure women knew they were participating in research, clarify details on their original application, and gather additional information about transportation and/or child care needs to participate (see Online Supplement 2 for a copy of the full intake survey). Two women could not participate in the PhotoVoice project due to scheduling conflicts, and another participant withdrew from the study for personal reasons. Ten women, drawn from the two larger towns and outlying regions in the county, participated in the project from enrollment to final presentation of results. Participants received a $75 stipend per PhotoVoice session as compensation for their time and travel expenses, up to a maximum amount of $300. Free child care and transportation were available to participants to attend the sessions.

PhotoVoice Process

Participants engaged in the PhotoVoice process over a 3-month period from September 2014 to December 2014. Prior to initiating study activities, participants provided consent and completed a four-page pre-study survey. The survey included questions on food habits (e.g., frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption, fast food consumption), food access, exercise habits, and mental and physical health. Participants repeated the survey at the end of the project. PhotoVoice Sessions 1 to 3 consisted of 3-hour workshops facilitated by the research team. These sessions were held in a central location in the community. For the fourth and final session, participants could either participate in an exhibit of the PhotoVoice findings during a local art walk in the town that serves as the county seat and/or help present findings during a CHART meeting. Research team members recorded detailed field notes of the conversations and interactions during all PhotoVoice sessions.

Session 1 oriented participants to the project goals, PhotoVoice method, and reviewed the study tasks and timeline. Research team members gave a brief presentation on epigenetics and the impact of maternal nutrition on the health of the child and future adult, and engaged the participants in a discussion about factors that shape eating behaviors and how those factors might be captured in photographs. We did not present a specific diet, nutrients, or foods as the “right” way to eat healthy. During the meeting, participants reflected on factors affecting their eating habits that they perceived to be in their control or outside their control. Participants received a digital camera and were trained by a local photographer on use, including image composition and lighting. Between Sessions 1 and 2, participants were asked to photograph 20 things that make it harder to eat healthy and 20 that make it easier. We encouraged participants to take half of these pictures in the community and half at home. Participants also received a notebook to journal about their experiences. Participants returned the camera’s memory cards in a self-addressed, stamped envelope to the study’s local community liaison; hard copies of the photographs were developed prior to Session 2.

Session 2 focused on critical reflection and dialogue about the photographs. Our research team facilitated a three-step process described by Wang and colleagues that involves selecting, contextualizing, and codifying the images (Wang & Burris, 1997; Wang & Pies, 2004). First, participants individually reviewed their images and chose several images that most resonated with them as factors that act as barriers or facilitators to healthy eating. Second, participants used a modified SHOWeD guide (Wang & Pies, 2004) to describe what the images meant to them and prepare photo captions, and discussed their images in small groups. The modified SHOWeD guide included the following questions: What do you see here? What is really happening here? How does this relate to food choices? Why does this problem, concern, or strength exist? How could this image educate people? What can I/we do about it? Third, participants shared their photographs and captions as a large group; during this conversation, participants clustered photographs on a wall and discussed common patterns that their images revealed. Toward the end of Session 2, we brainstormed about how findings could be presented to the public during the planned community events as well as in other venues. Between Sessions 2 and 3, the project team prepared a draft PowerPoint presentation of images and themes based on participant suggestions, while participants took their photographs home to further refine the captions.

In Session 3, participants worked with study team members to finalize their captions and provided feedback on the draft PowerPoint Exhibit. In addition, the research team encouraged participants to think beyond individual behavior change and to explore how different aspects of their environment (e.g., home, community, organizational, societal) influenced personal eating behaviors. We asked them to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of their families and communities in supporting healthy eating and to suggest interventions that might improve nutrition for women of childbearing age. Between Sessions 3 and 4, the community liaison met individually with participants to audio record their finalized captions for the PowerPoint presentation. For Session 4, participants chose to attend either an exhibit of their photos and captions at a local gallery and/or co-present project findings during a monthly CHART meeting. Both options allowed for interaction and discussion with the public, which included responding to audience questions.

Data Analysis

We approached data analysis as an iterative process. Following each PhotoVoice session, study team members held 1- to 3-hr debriefings to reflect on session content, participant actions and comments, and to identify areas warranting additional exploration. Although we initially planned to categorize images in terms of “home” and “community” factors, the richness that was emerging in these conversations led our team to explore alternative coding frameworks that allowed for additional levels of detail. We selected a socioecological model, which was designed to understand the dynamic interplay of personal and environmental factors at four levels: individual, relational, community/organizational, and societal (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Chacko & Chacko, 2010; Strack, Lovelace, Jordan, & Holmes, 2010).

Shortly after the final PhotoVoice session, four team members (i.e., Mabry, Farris, Forro, Davis) individually reviewed field notes from Sessions 1 to 3 and categorized participants’ selected images and associated captions into barriers and facilitators to healthy eating using the four-level socioecological model. Using each study team member’s individual categorization as a starting point, we then met collectively to review the images/captions and to identify emerging themes at each level of categorization. We used field notes from the four sessions’ discussions to clarify emerging themes and reconciled discrepancies between team members by consensus. Initial thematic patterns were reviewed and discussed with the full study team for final refinement. Several images represented more than one level of the socioecological model, suggesting overlap among the four spheres of influence.

Results

The 10 participants ranged in age from 22 to 46 years of age (median = 33.7 years), and the median household income was between $20,001 and $30,000. The majority of the participants reported an annual household income of $30,000 or less; the remaining reported an income of $40,001 to $50,000 or income greater than $100,000. Six participants (60%) reported employment outside the home, and all of the participants had children. Attendance at the four PhotoVoice sessions was high. The women who missed a session met privately with the community liaison to receive instruction, review/receive study materials, and share their thoughts and ideas while completing session tasks.

Participants took 354 total photographs during the PhotoVoice project, with an average of 32 photographs per individual (range: 15 to 42 photographs). Participants selected 62 photographs (42 with captions, 16 referenced during group discussions) that represented factors that acted as barriers or facilitators to healthy eating. During group discussions, participants were surprised by their overlap in experiences, which they shared regardless of their incomes, employment, or education. The emergent themes are described within the four levels of the socioecological model below.

Individual-Level Factors

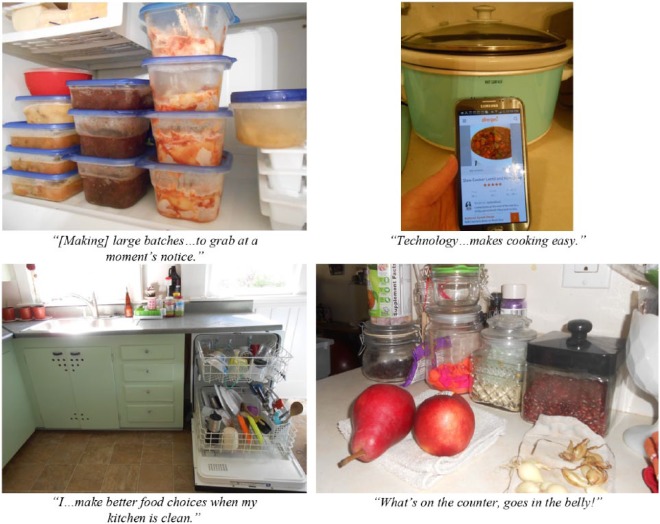

Participants described how taking control of their environments and understanding what constitutes healthy eating enabled them to make healthier choices. They often did this by preparing in advance and keeping healthy food at the ready. Examples of participants preparing in advance include clipping coupons to help them spend wisely stocking up on healthy ingredients and having supplies “at the ready,” having a clean kitchen that facilitated meal preparation, keeping healthy foods (and not junk food) on the counter, and preparing healthy meals ahead of time. Figure 1 displays a compilation of images from this category. One woman commented on the photo of her pantry:

Food storage . . . motivates you to use the resources that you have. Food storage allows me to cook with ingredients that are healthier—and not be tempted to buy fast food or easy quick foods that tend to be higher in sugar and sodium.

Figure 1.

Example photographs and captions illustrating individual-level factors that influenced participant food choices.

Participants also commented on how they used technology to identify healthy recipes and crockpots to make it easier to prepare healthy meals.

Participants also photographed images to emphasize how knowledge of healthy food options and meal prep strategies helped them eat healthy. One participant took a picture of a plate with bright, hand-drawn food items, which was on display at her doctor’s office. She commented that knowing what a healthy plate looks like, including portion size, can help people maintain a healthy weight. Another woman with a chronic illness took pride in her knowledge about healthy eating. She captured this with a picture of a salad that she made at home, noting that healthy eating to manage an illness “can be fun, creative, and flavorful.” A mother with a young child took a picture of her fridge filled with single and two-serving dishes of prepared meals, which she titled “Food bank.” She wrote,

Being a first time mom on a shoestring budget, with no child care, I learned fast that eating healthy took effort, planning and two hands! I cross referenced my recipes with what was allowed by the WIC vouchers, found ways to get the baby to sleep (in the backpack), then I made large batches of healthy meals and stored them in single-serving containers that are ready to grab at a moment’s notice . . . With one hand.

Individual-level barriers to healthy eating often revolved around perceptions of lack of self-control such as by having unhealthy food easily available, inadequate prior preparation, emotional eating, and the addictive power of sweets. One woman captioned two complementary photographs, one with fruit on the counter, one with chips as “What’s on the counter, goes in the belly. So watch it!” The women commented on unhealthy foods being tasty, and the difficulty of limiting themselves to a single cookie. Being “stressed, tired, or out of time” was also identified as a barrier to healthy eating. Participants described how seasonality and weather patterns shaped their motivation to eat healthy as well as the types of food that were easily available (e.g., sugar during the holidays). For example, one woman took a picture of her daughter with an umbrella in the rain. Her caption noted that during the rainy season, “fresh, local produce is scarce, and I feel less inclined to exercise. When I’m aware of the seasonal challenges, I am more conscious about my food choices.” Many participants perceived that barriers to healthy eating at the individual level could be ameliorated by being aware of how life’s context affects eating behaviors and by preparing food in advance.

Relational-Level Factors

Social connections and relationships with family, friends, medical clinicians, and significant others played an important role in shaping the women’s eating behaviors. The women noted the positive influence of friends, clinicians, and other support systems, including in-person relationships as well as through texting friends and holding each other accountable. One participant described learning how her mother had taught her to buy healthy foods as a child, noting that “we clipped coupons, watched for sales, and went to the store with a list.” Friends were also identified as a motivating factor in healthy eating habits, for example, by sharing recipes or food, holding each other accountable for what one consumed, and helping daily meal planning. Medical providers also influenced healthy eating habits. One participant took pictures of her doctor’s office and explained that “having a real discussion with your doctor about healthy weight management can help guide you to make better nutritional choices.” Having young children also motivated some participants to eat healthy. A photograph taken of a plate of sugar cookies led one participant to reflect on how having her son enabled her to overcome the addictive nature of sweet, unhealthy foods. She wrote,

When my baby was young I had to change my diet so that he wasn’t crying all the time. I became vegan and eliminated sugar, milk, and other items from my diet. I felt better and he was finally able to sleep through the night. But . . . I’m addicted to sugar! Now that he’s older he doesn’t cry so much in response to what I eat. I feel tired all the time and think about changing my diet to eat healthier again, but it’s so much harder for yourself (no one to be accountable to).

Notably, spouses and partner relationships were perceived as barriers to healthy eating. As displayed in Figure 2, one participant’s photograph showed her partner holding a package of sweets while she held a bag of fruit. In another image, a woman captured how her male partner brought out the cookies, and the temptation to eat them, in the evening after the children were in bed. The women commented that it can be hard to choose the “healthier” items when there were multiple diet preferences in the household, particularly when there was also a limited food budget.

Figure 2.

A couple holding fruit and cookies, a situation that demonstrates factors that influenced food choices on the relational level.

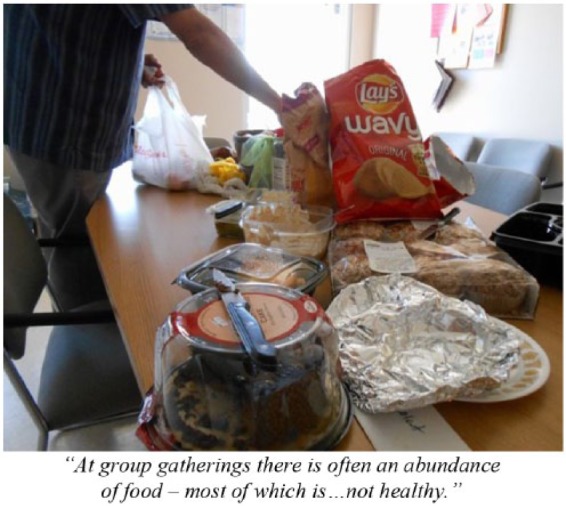

Community-/Organizational-Level Factors

Participants identified several factors at the community and organizational level that influenced their eating habits including availability, awareness, and accessibility of nutritious foods. Many photos depicted opportunities for foraging, hunting, and community gardening. Participants noted that these behaviors were “normal” in their community and facilitated healthy eating. Using a photo of antlers from a recent hunting trip, one participant acknowledged that having an inexpensive supply of protein helped her family eat healthier throughout the year. Farmers markets and a local produce truck that provided fruits and vegetable bags to low-income people were also identified as facilitators to healthy eating.

Foods provided during social gatherings in the community (e.g., church events) or at work gatherings could either help or hinder healthy eating behaviors. One participant reflected on a church gathering that served salad and other vegetables, noting this supported her efforts to eat healthy. In contrast, as depicted in Figure 3, another woman took a picture of a potluck day at her workplace. She described that these group gatherings usually had an abundance of unhealthy food that was “high fat, high carb, highly processed.” This participant suggested that work-sites should develop policies to support healthy eating, shifting some of the responsibility for making healthy choices from the individual to a larger organizational context.

Figure 3.

A work potluck, an example of factors that influenced food choices on the community/organizational level.

All participants noted that access to healthy food options in the community, particularly when running errands, was limited and created barriers to healthy eating. One participant noted, “We are bombarded by eating poorly while we are out.” She photographed a grocery cart with her children and a package of sushi from the store and wrote the following caption: “Eating on the go can be tricky, especially if you have kids. You have lots of options that you can drive-through but most are fast food or coffee shops.”

Societal-Level Factors

The only factor identified as a facilitator in this category was the use of coupons. One participant took a picture of a coupon ad from the local newspaper and explained,

Because of the cost of my housing, my family’s main source of food income comes from my EBT [Electronic Benefits Transfer, an electronic system that issues welfare benefits]. Living in the community that we do, it does not go far. Coupons help our food income stretch much further than if we were not to use them.

However, participants also noted that most coupons are for unhealthy foods, rather than for produce or nutritious options. One woman wrote, “It’s a shame in our society that the cheap and easy options tend to be the most unhealthy.”

Participants also noted that marketing could be detrimental to nutritious eating. One participant described a photo of the “Natural Foods” isle in the local market by saying, “Putting products in the natural choices section gives a misleading impression that they are healthy. Just because it is organic or GMO free doesn’t make it good for us.” Another participant photographed caramel popcorn samples at the farmers market and noted that marketing of unhealthy foods even occurs in locations that are supposed to be “safe zones” where access to nutritious fruits, vegetables, and unprocessed foods is the goal.

Over the course of the project, participants reflected on how cultural norms affect their food choices, frequently in detrimental ways, through holiday traditions that promoted the consumption of sweets, financial demands leading to busy work schedules and limited time for preparing healthy meals, and discordant expectations of women presented in the media. With regard to the influence of holidays, one participant described a pile of candy with the following caption:

Candy is a part of many celebrations in our culture. There is a constant stream of sugar treats that come into our home without any effort—birthdays, holidays, parades, school rewards, and more. It is challenging to keep my family from consuming these fun, colorful, tasty treats.

Participants also noticed that limited time often led them to choose fast, inexpensive convenience foods. One participant photographed a clock and wrote the following caption: “Most families need two income earners, leaving little time for preparation of healthy foods.” Another woman commented that if given the choice between spending time with her family and preparing healthy meals, she would rather spend time with her family.

As depicted in Figure 4, participants noted they often received competing messages around health and nutrition in our society. This participant took a picture of two contrasting magazine covers located side-by-side in the grocery check-out aisle. One cover had a thin and muscular woman; the other showed a big chocolate Bundt cake. She used the picture to show how our culture sets up unrealistic expectations for women: Without any display of effort, you should have the perfect body, family, and life, and eat cake too!

Figure 4.

The magazine rack at a grocery store, an example of factors that influenced food choices at the societal/structural level.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to engage rural women of childbearing age in identifying environmental, behavioral, and cultural factors that facilitate or hinder healthy eating choices. Using the PhotoVoice methods, 10 participants took photographs and wrote captions identifying factors that shaped their eating behaviors at the individual, relational, community/organizational, and societal levels. At the individual level, participant described how self-control (e.g., prior preparation, knowledge of healthy eating, self-awareness regarding emotions and seasonality), or a lack thereof, shaped eating patterns. Relationships with parents, friends, medical providers, and children were frequently viewed by participants as facilitators by providing access to information, motivation, and accountability for healthy eating. Interestingly, participants noted that spouses and partners often made it harder to eat healthy as they preferred less nutritious options (e.g., cookies over fruit).

When taking their photographs and during session discussions, participants began to recognize that their eating behaviors were shaped by factors beyond individual habits or relational influences and through structures in the broader community. This included having access to both healthy options in the natural environment (e.g., foraging, community gardens) and unhealthy options in the town (e.g., coffee shops, fast food). Social events, such as those held at church or during work, could either make it easier or harder to eat healthy based on the meal selection (e.g., home-made salads or highly processed foods). Ease of access to gardens in the community or at home as well as hunting/foraging options were identified as community-level facilitators, and may be a factor amplified in rural environments. In general, participants noted how societal factors such as cultural norms and marketing made it harder to eat healthy; coupons were primarily for unhealthy food choices, stores advertised low-nutrient, highly processed foods as “non-GMO” and organic, and American holidays encourage the overconsumption of candy and foods. Participants also discussed how “society” and the media created challenging expectations for women and families to “have it all.” This was observed in the tensions between time with family and preparing healthy foods, two parents working and limited time for healthy food prep, and in expectations about the ideal woman while encouraging the consumption of rich “comfort” foods.

Many of the barriers and facilitators to healthy eating that we identified in this sample of rural women of childbearing age resonate with prior research. For example, the high cost of healthy food and the challenge of making time to prepare healthy meals were perceived barriers for all of our participants. Multiple studies note the challenges of eating a healthy diet on a minimal budget (e.g., Cassady, Jetter, & Culp, 2007; Drewnowski & Darmon, 2005; Wiig & Smith, 2009). Socioeconomically disadvantaged groups have been shown to make fewer healthy food choices (van Lenthe, Jansen, & Kamphuis, 2015), and to eat fewer fruits and vegetables (Giskes, Avendano, Brug, & Kunst, 2010). One recent study found that low-income female participants were more likely to shop for produce at the farmers market if prices were lower (McGuirt et al., 2014). However, we found that all women in our study perceived cost of healthy food as a barrier, including those who reported incomes more than $30,000 a year. This finding may suggest that regardless of socioeconomic status, these women allocated only a certain fraction of income and time for good nutrition.

The barrier of limited time for food preparation paralleled findings from studies with low-income women in New York and college students (Garcia, Sykes, Matthews, Martin, & Leipert, 2010; Valera, Gallin, Schuk, & Davis, 2009). Interestingly, although some of our participants felt they lacked skill in preparing inexpensive healthy foods, none of the participants in our study expressed that a lack of knowledge about nutrition or what was considered healthy was a barrier to healthy eating. Knowledge was also not a factor for low-income women in New York, who frequently referred to the food pyramid and understood the need to eat whole grains and vegetables (Valera et al., 2009). A survey of socioeconomically disadvantaged women in Australia, however, found that low confidence in the ability to cook and shop for healthy food was a barrier to avoiding fast food consumption, independent of income (Thornton, Jeffrey, & Crawford, 2013). Future studies should consider whether participant self-reported confidence in their knowledge of healthy eating is associated with the current evidence-base around nutrition. In addition, research is needed to assess how individual-level factors interact with environmental-level factors to shape healthy eating (Thornton et al., 2013). Similar studies with rural women who may have lower skills, knowledge, and interest in nutrition may be warranted, as the interventions needed for these populations may be distinct.

Although community factors and cultural norms are viewed as a powerful force in shaping eating behaviors in the research literature (Larson & Story, 2009), it is important to note that participants in our study initially identified personal shortcomings as the primary factor influencing their eating habits when they were less than healthy. Yet, over the 3-month study, the conversation shifted from individual successes and failures to a recognition of the influence relational, community, and cultural factors played as the participants discussed their photographs and captions as a group, and realized that there were many similarities in their experiences around eating healthy, despite diverse personal backgrounds. These shared experiences encouraged participants to look beyond self-blame and personal behavior to acknowledge the influence of a larger societal context on their dietary habits. As part of this process, participants frequently suggested solutions that could be implemented at the community/organizational levels to make healthy eating easier, such as by implementing workplace policies to encourage nutritious options during gatherings, and petitioning the Women Infants and Children (WIC) program to distribute crockpots and provide applicable recipes cross-referenced against WIC vouchers. Participants also realized that exposure to “junk food” marketing is largely out of their control, necessitating changes at local and national marketing and policy levels.

There are a few notable limitations of this study. First, only 10 participants completed the project, which may suggest that we have not captured all of the barriers and facilitators to healthy eating in this population. Although this is a small sample size, Catalani and Minkler (2010) found 13 was the median number of community participants in 37 published PhotoVoice initiatives, with a range from four to 122 participants. In addition, the overlap in image selection and agreement during group discussions suggests that we were able to achieve a comprehensive view of the factors that shape food choices. However, although we attempted to recruit from the Hispanic population, we were unable to engage individuals from that segment of the community to participate, and additional work with this population may be necessary. Second, this study occurred during one Fall and early Winter season, so participant travel would be completed before the winter holidays and weather impeded access to our centralized location. Participants had less than 2 weeks to take their photographs, and several expressed a desire to have more time to reflect on the topic and take photographs. A recent systematic review of the PhotoVoice methodology and literature showed the median duration of a study to be about 4 months (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). Finally, participants in this study may not be representative of the larger population of rural women of childbearing age in this community. Although participants in our study represented the full spectrum of age and socioeconomic status among women of childbearing age in the region, they may have also had greater knowledge and interest in eating healthy, which has been shown to predict healthy eating (Michaelidou, Christodoulides, & Torova, 2012). Given that our participants still encountered considerable challenges to healthy eating, our findings on multi-level barriers provide one starting point for future interventions.

Given what we know about the importance of maternal nutrition in chronic disease prevention and the health of future generations (i.e., Barger, 2010), the results of this study reflect a need to improve rural women’s food environments. In our lower earning participants’ experience, welfare programs do not afford them enough support to eat healthy, unprocessed, fresh foods. For higher earners, further research is needed to establish whether placing a low value on healthy foods interferes with good nutrition. Public health marketing for improved nutrition for all socioeconomic groups, as well as affordable produce through subsidized programs, may be needed to avert the looming chronic disease crisis in future generations. In addition, our participant images/captions and group conversations revealed that nutrition behaviors were influenced by multiple inter-related factors across the levels of the socioecological model. Interventions to support healthy eating in rural women of childbearing age should be multi-component by targeting specific individual, relational, community/organizational, and societal factors as well as accounting for the interrelationship among these levels.

Conclusion

Few studies have explored the factors that shape nutrition behaviors for rural women of childbearing age. Our PhotoVoice study highlights how factors at four levels facilitate or impede healthy eating in this population, including individual (e.g., self-control/awareness, prior preparation), relational (e.g., family, friends, clinicians, partners), community/organizational (e.g., presence/absence of healthy options, policies to support healthy eating), and societal factors (e.g., cultural expectations, marketing). Efforts to improve eating habits for rural women of childbearing age should include multi-component interventions and policies to facilitate healthy eating through changes at all levels of the socioecological model. Such interventions have the potential to improve nutrition behaviors and health in the current generation, and in generations yet to come.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the support our partners provided in conducting this study: Sarah Egan, MPH, CCRP, CHES, assisted with the PhotoVoice training sessions and dissemination activities; Grace Laman, RD, answered questions about healthy eating; and James Olson provided training on photographic composition. We also appreciate the support of the City of Astoria Parks and Recreation Department, Astoria School District, members of Clatsop County CHART, and, of course, the participants who all took time out of their busy lives as mothers and breadwinners to join the study.

Author Biographies

Julia Mabry, MS, is the community liaison for the Oregon Rural Practice-Based Research Network and the North Coast Research Coalition. She is based in Astoria, Oregon, the United States.

Paige E. Farris, MSW, is the program manager for the Integrated Program in Community Research and Project Director for Oregon’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network in the School of Public Health at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). She is based in Bend, Oregon, the United States.

Vanessa A. Forro, BA, is a research assistant for the Oregon Rural Practice-Based Research Network and Veterans Administration Portland Health Care System. She is based in Portland, Oregon, the United States.

Nancy E. Findholt, PhD, RN, is an associate professor for the OHSU School of Nursing. She is based in La Grande, Oregon, the United States.

Jonathan Q. Purnell, MD, is a professor in the Department of Medicine, Divisions of Endocrinology and Cardiovascular Medicine and an associate director of the OHSU Bob and Charlee Moore Institute for Nutrition and Wellness, Portland, Oregon, the United States.

Melinda M. Davis, PhD, is a research assistant professor in the OHSU Department of Family Medicine and the Director of Community Engaged Research for the Oregon Rural Practice-Based Research Network in Portland, Oregon, the United States.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The study protocol was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Institutional Review Board (#10815), and participants provided informed consent.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported through a partnership with The Bob and Charlee Moore Institute for Nutrition and Wellness at Oregon Health & Science University. Dr. Davis is supported in part by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality-Funded Patient Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) K12 award (Award Number 1 K12 HS022981 01).

References

- Barger M. K. (2010). Maternal nutrition and perinatal outcomes. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 55, 502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J. (1997). Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition, and disease in later life. Nutrition, 13, 807–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. M. (2003). Micronutrient deficiencies and cognitive functioning. The Journal of Nutrition, 133, 3927S–3931S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassady D., Jetter K. M., Culp J. (2007). Is price a barrier to eating more fruits and vegetables for low-income families? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107, 1909–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C., Minkler M. (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37, 424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html

- Chacko L. R., Chacko S. A. (2010). Modern public health systems. In Andresen E., DeFries Bouldin E. D. (Eds.), Public health foundations: Concepts and practices (pp. 25–47). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Community assessment: A collaborative effort to create shared knowledge about the community. (2013). Clatsop County Public Health Department. Retrieved from http://www.co.clatsop.or.us/sites/default/files/fileattachments/public_health/page/691/clatsop_assessment_2013.pdf

- Community Health Advocacy and Resource Team. (2015). History. Retrieved from http://www.clatsopchart.org/?page_id=629

- Crider K. S., Bailey L. B., Berry R. J. (2011). Folic acid food fortification—Its history, effect, concerns, and future directions. Nutrients, 3, 370–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boo H. A., Harding J. E. (2006). The developmental origins of adult disease (Barker) hypothesis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 46(1), 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A., Darmon N. (2005). Food choices and diet costs: An economic analysis. The Journal of Nutrition, 135, 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy L. (2011). “Step-by-step we are stronger”: Women’s empowerment through photovoice. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 28, 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findholt N. E., Michael Y. L., Davis M. M. (2011). Photovoice engages rural youth in childhood obesity prevention. Public Health Nursing, 28, 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney-Brown T. (2011). Epigenetic consequences of maternal nutrition: A review of contemporary research. Journal of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine, 30(1), 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. C., Sykes L., Matthews J., Martin N., Leipert B. (2010). Perceived facilitators of and barriers to healthful eating among university students. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 71(2), e28–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giskes K., Avendano M., Brug J., Kunst A. E. (2010). A systematic review of studies on socioeconomic inequalities in dietary intakes associated with weight gain and overweight/obesity conducted among European adults. Obesity Reviews, 11, 413–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardeau M. P., Healey G., Ford J. (2011). The use of photovoice to document and characterize the food security of users of community food programs in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Rural and Remote Health, 11, 1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson N., Story M. (2009). A review of environmental influences on food choices. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38, 56–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N., Garcia A. C., Leipert B. (2010). Photovoice and its potential use in nutrition and dietetic research. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 71, 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirt J. T., Pitts S. B. J., Ward R., Crawford T. W., Keyserling T. C., Ammerman A. S. (2014). Examining the influence of price and accessibility on willingness to shop at farmers’ markets among low-income eastern North Carolina women. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46, 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidou N., Christodoulides G., Torova K. (2012). Determinants of healthy eating: A cross-national study on motives and barriers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. Y., Vardell R., Lower J. K., Kinter-Duffy V. L., Ibarra L. C., Cecil-Dyrkacz J. E. (2010). Empowering women through photovoice: Women of La Carpio, Costa Rica. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 5, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Morley R., Lucas A. (1997). Nutrition and cognitive development. British Medical Bulletin, 53, 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack R. W., Lovelace K. A., Jordan T. D., Holmes A. P. (2010). Framing photovoice using a socio-ecological logic model as a guide. Health Promotion Practice, 11, 629–636. Retrieved from http://hpp.sagepub.com/content/11/5/629.long [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton L. E., Jeffery R. W., Crawford D. A. (2013). Barriers to avoiding fast-food consumption in an environment supportive of unhealthy eating. Public Health Nutrition, 16, 2105–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). State & county Quickfacts: Clatsop County, OR. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/41/41007.html

- Valera P., Gallin J., Schuk D., Davis N. (2009). “Trying to eat healthy”: A photovoice study about women’s access to healthy food in New York City. Affilia, 24, 300–314. [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe F. J., Jansen T., Kamphuis C. (2015). Understanding socio-economic inequalities in food choice behaviour: Can Maslow’s pyramid help? British Journal of Nutrition, 113, 1139–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. C. (2003). Using photovoice as a participatory assessment and issue selection tool. In Minkler M., Wallerstein N. (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health (pp. 179–196). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. C., Burris M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24, 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. C., Pies C. A. (2004). Family, maternal, and child health through photovoice. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 8, 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiig K., Smith C. (2009). The art of grocery shopping on a food stamp budget: Factors influencing the food choices of low-income women as they try to make ends meet. Public Health Nutrition, 12, 1726–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F. W., Cudd T. A., Meininger C. J., Spencer T. E. (2004). Maternal nutrition and fetal development. The Journal of Nutrition, 134, 2169–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]