Abstract

Background

Evidence has suggested that neurobiological deficits combine with psychosocial risk factors to impact on the development of antisocial behavior. The current study concentrated on the interplay of prenatal maternal stress and autonomic arousal in predicting antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits.

Methods

Prenatal maternal stress was assessed by caregiver’s retrospective report, and resting heart rate and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) were measured in 295 8- to 10-year-old children. Child and caregiver also reported on child’s antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits.

Results

Higher prenatal maternal stress was associated with higher caregiver-reported antisocial and psychopathy scores, even after the concurrent measure of social adversity was controlled for. As expected, low heart rate and high RSA were associated with high antisocial and psychopathic traits. More importantly, significant interaction effects were found; prenatal stress was positively associated with multiple dimensions of psychopathic traits only on the conditions of low arousal (e.g., low heart rate or high RSA).

Conclusions

Findings provide further support for a biosocial perspective of antisocial and psychopathic traits, and illustrate the importance of integrating biological with psychosocial measures to fully understand the etiology of behavioral problems.

Keywords: antisocial behavior, psychopathy, prenatal maternal stress, heart rate, vagal tone

Conduct problems and antisocial behaviors are key features of Conduct Disorder (CD) and are defined by age-inappropriate actions and attitudes that infringe family expectations, societal norms and the property rights of others (McMahon, Wells, & Kotler, 2006). Such behavioral problems in children are generally regarded as a precursor to juvenile delinquency and later criminal offending. While only 5% of individuals display early, chronic, and extreme antisocial behaviors (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003), they account for almost 50% of crime in the United States (Loeber, Burke, Lahey, Winters, & Zera, 2000). Because of these disproportionate and staggering rates, conduct problems in youth are one of the most costly mental health issues for the nation, as the educational, health, social service, and criminal justice systems are all involved in its intervention (Welsh, Loeber, Stevens, Stouthamer-Loeber, Cohen, & Farrington, 2008). The latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes a specifier for CD labeled as “with limited prosocial emotions,” which refers to callous-unemotional (CU) or psychopathic traits in children, characterized by callousness, uncaring behavior, deficient guilt, and lack of empathy (Blair, Leibenluft, & Pine, 2014). CU traits, together with grandiose-manipulative and daring-impulsive traits, are considered the three dimensions that characterize the psychopathic traits in children and adolescents (Frick, 2004). Investigating aggression, delinquency, and psychopathic traits in youth is paramount to improving knowledge on the etiology of behavioral problems and CD, which may serve to prevent at-risk populations from these adverse outcomes later in life.

Both biological and psychosocial risk factors have been linked to antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits. One robust biological correlate is low resting heart rate. In a meta-analysis of 40 studies, Ortiz and Raine (2004) found a significant and moderate effect size (d = −0.44, p < .0001) for resting heart rate and concluded that it is a consistently replicated predictor of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. Vagal tone, as indexed by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) or high frequency heart rate variability, reflects the influence of the parasympathetic nervous system on cardiac activity and has also been linked to antisocial behavior. RSA refers to the variability of heart rate across the respiration cycle due to the influence of the vagus nerve on the sinoatrial node (Beauchaine, 2001; Grossman, van Beek, & Wientjes, 1990). High RSA (together with low heart rate) has been found to correlate with more externalizing behavioral problems in children (Dietrich et al., 2007; Scarpa, Fikretoglu, & Luscher, 2000). It has been argued that a predominance of parasympathetic over sympathetic activity or excessive vagal tone indicates a passive vagal coping response to stress, which in turn may contribute to both low heart rate and more antisocial behaviors (Raine & Venables, 1984; Venables, 1988). Taken together, autonomic underarousal (i.e., low heart rate and high RSA) may be a biological marker of low level of fear, which contributes to violent and antisocial acts (Raine, 1993). Alternatively, low autonomic arousal may be an undesirable physiological state that motivates antisocial individuals to carry out stimulating activities (e.g., antisocial behaviors such as robbery or assault) to raise their arousal to an optimal level (Raine, 2002).

In the psychosocial spectrum, studies have linked prenatal risk factors (e.g., maternal stress, prenatal depression and/or anxiety) to antisocial behaviors and psychopathic traits (e.g., Mäki et al., 2003; Van den Bergh & Marcoen, 2004). Prenatal maternal stress predicts delinquency (Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & van Kammen, 1998), and the cumulative prenatal risk, including maternal psychopathology and partner relationships, predicts fearless temperament in early childhood and CU traits by early adolescence (Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin, & Maughan, 2011). Taken together, evidence suggests that prenatal maternal stress is associated with elevated risk of conduct problems in the offspring. It has been argued that during pregnancy, activation of the mother’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in response to distress and the subsequent release of glucocorticoids (GC), such as cortisol, may pass through the placenta and influence fetal brain development and later behavioral outcomes (Bergman, Sarkar, Glover, & O’Connor, 2010; Challis et al., 2001; Matthews, 2000; Werner et al., 2013). For example, fetal exposure to increased levels of maternal cortisol throughout human gestation predicts negative reactivity and difficult behavior during infancy (Davis, Glynn, Schetter, Hobel, Chicz-Demet, & Sandman, 2007; de Weerth, van Hees, & Buitelaar, 2003). Alternatively, fetal exposure to high levels of maternal cortisol in early gestational period may have an effect on brain development. For example, elevated maternal cortisol levels have been found to be associated with increased amygdala volume in 7-year-old females, which in turn was associated with more affective problems (Buss, Davis, Shahbaba, Pruessner, Head, & Sandman, 2012). Sarkar and colleagues (2014) found that greater maternal prenatal stress was related to modifications in the development of white matter connections in the limbic-prefrontal areas (e.g., right uncinate fasciculus fractional anisotropy and bilateral uncinate fasciculus perpendicular diffusivity) in 7-year-olds. Structural and functional abnormalities in above areas, including the amygdala in particular, have been associated with conduct problems and psychopathic traits in children and adolescents (e.g., Marsh et al., 2008; Jones, Laurens, Herba, Barker, & Viding, 2009; Sterzer, Stadler, Poustka, & Kleinschmidt, 2005). Taken together, prenatal maternal stress may be associated with atypical development of brain, which in turn predisposes individuals to antisocial and psychopathic behavior problems.

Although neurobiological and psychosocial risk factors have long been independently linked to antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits, increasing evidence suggests that the presence of both risk factors significantly increase the rates of antisocial behavior (Raine, 2002). For example, Farrington (1997) found that boys with low resting heart rates who also had a poor relationship with their parental figures and came from larger families were more likely to become violent offenders as adults. In a recent study, lower resting heart rate was found to be associated with higher scores on the daring-impulsive factor of psychopathy and aggression in the presence of high social adversity (Raine et al., 2014). In a sample of 7- to 13-year-old community children, Scarpa, Tanaka, and Haden (2008) found that witnessed community violence was positively associated with aggression only in conditions of high vagal tone. It has been proposed that genetic predispositions lead to biological risk factors (e.g., autonomic underarousal) that may bring about antisocial behavior, but the presence of perinatal and prenatal risks may additionally contribute to developing such biological impairments.

In the current study, our objectives were (1) to determine the extent to which a retrospective measure of prenatal maternal stress explains variance in antisocial and psychopathic behaviors in children, above and beyond the concurrent measure of social adversity, which has been associated with externalizing behaviors, and (2) to investigate the moderating effect of autonomic arousal on the above relationship. Based on prior literature, it was hypothesized that (a) greater prenatal maternal stress would be associated with higher aggression, delinquency, and psychopathic traits, even after the effects of social adversity is controlled for; and (b) the above associations would be moderated by autonomic arousal, so that children with high prenatal maternal stress who also had low arousal (e.g., low heart rate or high RSA) would exhibit highest scores on the antisocial and psychopathic measures.

Methods

Participants

The sample for this study consisted of 8- to 10-year old boys and girls (Mean age = 9.05, SD = 0.61, Mean IQ = 101.66, SD = 20.68) living in Brooklyn, New York. Children with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder, mental retardation, or a pervasive developmental disorder were excluded. The sample included 295 children (141 male, 48.1%) with ethnicity breakdown as follows: 7.2% Hispanic, 21.2% Caucasian, 48.5% African-American, 3.1% Asian, and the remaining 20% of mixed/other. Caregiver participants were primarily biological mothers of the children (86.4%), although other relatives were also interviewed, including biological fathers (10.8%). Participants and their main caregivers were invited to the university for a 2-hr laboratory assessment including behavioral interviews, neurocognitive testing, psychophysiological recording, and social risk factor assessment. Incentives were provided to the participating families at the end of the assessment. All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board, and both parental consent and child assent were obtained. More detailed description of the sample can be found in Gao, Borlam, and Zhang (2015).

Measures

Prenatal maternal stress

Previous research investigating maternal stress during pregnancy and its effects on childhood behavioral problems has operationalized prenatal maternal stress by asking mothers whether they experienced events that caused them severe distress (i.e., financial difficulty, illness or death of relatives), and if their pregnancies were unwanted versus wanted (Park et al., 2014). Other studies have asked about the presence of crime, maternal affective disorder (Barker et al., 2011), and if the mother was looking forward to having a baby (Buchmann et al., 2014). Similarly, the current study inquired about events that might have caused maternal psychological distress at the time of pregnancy via a semi-structured psychosocial interview conducted with the caregiver. One point was scored if each of the following had happened during the pregnancy: divorce/separation, job changed/fired from job, moving, being a crime victim, financial problems, trouble with the law, accident, natural disaster, conflicts with significant other, illness or death of relatives/significant other, own physical illness, and own mental illness. The caregiver also answered “yes” or “no” or “not at all”, “somewhat”, or “very” to questions such as: “Was this pregnancy planned (negatively coded)?” “How happy did the pregnancy make you (negatively coded)?” “Did you ever take steps to terminate the pregnancy?” and “Were you depressed after birth?” All answers were coded dichotomously [present (“yes” or “somewhat” or “very” vs. absent (“no” or “not at all”)] and summed up to form a measure of prenatal maternal stress. Sum scores ranged between 0 and 10 with a median of 2. Internal consistency was .78 for the current sample.

Social Adversity

A social adversity index was created based on caregiver’s answer to ten questions following prior literature (Gao, Raine, Chan, Venables, & Mednick, 2010; Raine, Yaralian, Reynolds, Venables, & Mednick, 2002; Zhang & Gao, 2015). A total adversity score was created by adding 1 point for each of the following variables: Divorced Parents (single parent family, remarriage, or living with guardians other than parents), Foster Home, Public Housing, Welfare Food Stamps, Parent Ever Arrested (either parent has been arrested at least once), Parents Physically Ill, Parents Mentally Ill, Crowded Home (five or more family members per room within the home), Teenage Mother (aged 19 years or younger when the child was born), and Large Family (having five or more siblings by 3 years of age). All items were scored either 0 (no) or 1 (yes), with higher total scores indicating higher social adversity.

Child Psychopathy: The Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick & Hare, 2001) and the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU, Frick, 2004)

The APSD is a 20-item behavior rating scale designed for parents to assess child and adolescent psychopathic features (Frick & Hare, 2001). The child and caregiver each responded on a three-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 2 (definitely true). A trained research assistant accompanied the child during the whole testing session and answered any question the child might have had. The caregiver filled out the questionnaires in a different room. For the purpose of the current study, the impulsivity (e.g., “acts without thinking”) and narcissism (e.g., “thinks he or she is more important than others”) subscales of the APSD were used to assess the daring-impulsive (DI) and grandiose-manipulative (GM) dimension of psychopathic personality traits, respectively (Salekin, 2015). Scores were summed to form the corresponding measures. The reliability and construct validity of APSD have been supported in numerous samples (e.g., Munoz & Frick, 2007; Poythress, Dembo, Wareham, & Greenbaum, 2006; Vitacco, Rogers, & Neumann, 2003). In the current sample, the reliability was acceptable for both child (.72 for DI and .74 for GM) and caregiver’s report (.76 for the DI and .73 for GM).

Both caregiver and child also filled out the 24-item caregiver- and self-report version of ICU and the score of CU traits was the sum of all items. The ICU was developed to provide a more comprehensive assessment of CU traits in order to overcome some of the psychometric limitations of the six-item APSD CU subscale. Items were scored on a four-point scale from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (definitely true). The reliability and construct validity of ICU scores have been supported in community and detained youth (e.g., Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, 2006; Kimonis et al. 2008; Roose, Bijttebier, Decoene, Claes, & Frick, 2010). In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .75 for the caregiver’s report and .71 for the child’s report.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) and Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991)

The caregiver completed the CBCL, a rating scale composed of 112 items concerning a child’s behavior within the past 12 months. Items are rated on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). For the purposes of the present article, only the aggression and delinquency subscale scores were used in our analyses. Coefficient alphas in the current sample were .87 and .71 for aggression and delinquency, respectively. Children completed the YSR, a 3-point rating scale composed of 118 items concerning their behavior now or in the past 6 months. Coefficient alphas in the present sample were .79 and .49 for the aggression and delinquency subscale, respectively.

Psychophysiological Data Acquisition and Reduction

All psychophysiological data were collected continually using a BIOPAC MP150 system and analyzed offline with AcqKnowledge 4.2 software (Biopac Systems Inc., Goleta, CA). Each of the measures below was averaged over the initial 2-minute rest period at the onset of the computerized tasks and the 2-minute rest period at the culmination of the computerized tasks. For any participant with unavailable or unsuitable data (due to movement) for either of the two rest periods, we used only the available rest period data for that participant. Participants were instructed to sit quietly and rest during the rest periods.

HR

Electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded using ECG100C amplifier with two pre-jelled Ag-AgCl disposable vinyl electrodes placed at a modified Lead II configuration. The research assistant cleaned the contact area using rubbing alcohol and a cotton swab prior to affixing the electrodes. The recorded ECG signal was visually inspected for artifacts, and then converted to R-R intervals using the AcqKnowledge automated modified Pan-Tompkins QRS detector. Heart rate was measured in beats per minute (bpm), based on the average of inter-beat intervals (IBI; R-R wave intervals). Resting heart rate were the average heart rate of the two minutes while children were instructed to sit quietly and rest.

RSA

RSA was derived from the ECG100C amplifier with a band pass filter of 35 Hz and 1.0 Hz and a RSP100C respiration amplifier with a band pass filter of 1.0 Hz and 0.05 HZ. Respiration was assessed using RSP100C amplifier by putting a respiration belt around the abdomen of the subject at the point of complete exhalation. The AcqKnowledge automated function for RSA analysis was utilized. This software followed the well-validated peak-valley method (Grossman et al., 1990), in which RSA was computed in milliseconds as the difference between the minimum and the maximum R-R intervals during respiration. Higher values reflect greater PNS activity while lower values indicate lower PNS activity (Gruber, Harvey, & Johnson, 2009). As all RSA variables are positive skewed (.61< skewness <.80), square root transformations were applied before further calculation.

Statistical Analyses

First, the relationships among main study variables were investigated by Pearson’s correlation. A series of hierarchical linear regression were then conducted with each of the antisocial outcomes as the dependent variable. Sex and social adversity were entered into the model as covariates in the first step, and in the second step, prenatal maternal stress and an arousal measure were entered. Subsequently, an interaction term for prenatal maternal stress and arousal was included. Significant interactions were further investigated using simple main effects analyses (Aiken & West, 1991). Separate analyses were conducted to examine the moderating effects of heart rate or RSA. A p value of < .05 was regarded as significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means and standard deviations for key variables and their intercorrelations are given in Table 1. As expected, prenatal maternal stress was highly correlated with social adversity, and both were significantly associated with most forms of antisocial and psychopathic traits. Heart rate was negatively associated with RSA, and positively linked to aggression and delinquency, whereas RSA was positively related to delinquency and CU traits. Finally, being male was associated with lower resting heart rate and higher aggression, delinquency, CU traits, and daring-impulsive traits.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Main Variables.

| Caregiver Report | Child Report | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal Stress | Social Adversity | Heart Rate | RSA | Sex | Agg. | Del. | CU | GM | DI | Agg. | Del. | CU | GM | DI | |

| Social Adversity | .399*** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Heart Rate | .076 | −.131* | 1 | ||||||||||||

| RSA | .033 | .130* | −.684*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Sex | −.011 | .037 | −.141* | −.025 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Caregiver Report | |||||||||||||||

| Agg. | .198*** | .227*** | −.127* | .083 | .143** | 1 | |||||||||

| Del. | .151** | .197*** | −.158* | .172** | .138* | .704*** | 1 | ||||||||

| CU | .152** | .098a | −.100 | .114a | .071 | .478*** | .481*** | 1 | |||||||

| GM | .213*** | .227*** | −.038 | −.033 | .063 | .639*** | .568*** | .515*** | 1 | ||||||

| DI | .171** | .221*** | −.073 | −.009 | .093a | .616*** | .538*** | .475*** | .594*** | 1 | |||||

| Child Report | |||||||||||||||

| Agg. | .122* | .137* | −.061 | .032 | .029 | .242*** | .195*** | .056 | .181** | .152** | 1 | ||||

| Del. | .070 | .105a | −.101 | .049 | .155** | .151** | .154** | .063 | .044 | .135* | .590*** | 1 | |||

| CU | .048 | .060 | −.126* | .105a | .158** | .218*** | .221*** | .200*** | .128* | .148** | .224*** | .366*** | 1 | ||

| GM | .164** | .144** | −.104 | .030 | .046 | .206*** | .138* | .107a | .138* | .144** | .552*** | .440*** | .271*** | 1 | |

| DI | .094a | .085 | −.111a | −.009 | .122* | .204*** | .137* | .058 | .125* | .124* | .632*** | .531*** | .298*** | .558*** | 1 |

| Mean | 2.55 | 2.970 | 85.13 | 127.49 | 0.49 | 5.06 | 1.93 | 17.71 | 1.87 | 2.60 | 10.28 | 2.06 | 18.89 | 2.38 | 2.59 |

| SD | 2.83 | 2.040 | 11.35 | 62.08 | 0.50 | 4.84 | 1.95 | 8.81 | 2.01 | 1.76 | 6.90 | 2.10 | 7.03 | 2.31 | 1.80 |

| N | 340 | 335 | 261 | 261 | 340 | 337 | 336 | 335 | 331 | 331 | 340 | 340 | 332 | 324 | 324 |

Note. Agg. = Aggression; Del. = Delinquency; CU = Callous-unemotional traits; GM = Grandiose-Manipulative traits; DI = Daring-Impulsive traits.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.10.

Prenatal Maternal Stress and Caregiver-Reported Behavioral Problems: The Moderating Effect of Heart Rate

Aggression

The results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis are presented in Table 2. In the first step, sex and social adversity together accounted for 5.4% of the variance of the aggression scores: being male and having higher social adversity were associated with higher aggression scores. When prenatal maternal stress and resting heart rate were added, the amount of variance accounted for rose to 9.8%; controlling for the child’s sex and social adversity, higher levels of prenatal stress was associated with higher aggression scores, although the effect of heart rate was only marginally significant. The addition of the prenatal stress × heart rate interaction term in step 3 did not significantly increase the amount of variance accounted for.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses between Prenatal Stress, Heart Rate, and Caregiver Reported Behavioral Problems

| Aggression | Delinquency | CU Traits | Grandiose-Manipulative Traits |

Daring- Impulsive Traits | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | .054** | .047** | .019a | .050** | .041** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.35 | 0.14 | 2.42 | .016 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 2.03 | .043 | 1.37 | 1.11 | 1.24 | .217 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.90 | .367 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 1.58 | .116 | |||||

| SA | 0.22 | 0.07 | 2.94 | .004 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 2.92 | .004 | 1.03 | 0.57 | 1.80 | .072 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 3.50 | .001 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 2.89 | .004 | |||||

| Step 2 | .044** | .041** | .024* | .017 | .018 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.33 | 0.14 | 2.28 | .023 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 1.79 | .074 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.03 | .307 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.88 | .379 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 1.47 | .143 | |||||

| SA | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.63 | .105 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.77 | .077 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.88 | .381 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 2.60 | .010 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 1.98 | .049 | |||||

| Prenatal Stress | 0.25 | 0.08 | 3.26 | .001 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.57 | .011 | 1.27 | 0.59 | 2.15 | .032 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 2.14 | .033 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 2.06 | .040 | |||||

| HR | −0.13 | 0.07 | −1.84 | .067 | −0.14 | 0.06 | −2.59 | .010 | −0.95 | 0.58 | −1.65 | .100 | −0.05 | 0.13 | −0.38 | .702 | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.92 | .360 | |||||

| Step 3 | .002 | .010a | .007 | .013* | .017* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.33 | 0.14 | 2.29 | .023 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 1.86 | .064 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.05 | .294 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.89 | .373 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 1.49 | .138 | |||||

| SA | 0.12 | 0.08 | 1.53 | .127 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.56 | .120 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 0.72 | .473 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 2.38 | .018 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 1.74 | .083 | |||||

| Prenatal Stress | 0.26 | 0.08 | 3.34 | .001 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 3.00 | .003 | 1.46 | 0.61 | 2.41 | .017 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 2.53 | .012 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 2.53 | .012 | |||||

| HR | −0.12 | 0.08 | −1.64 | .103 | −0.13 | 0.06 | −2.27 | .024 | −0.76 | 0.59 | −1.27 | .204 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.03 | .979 | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.43 | .666 | |||||

| Prenatal Stress x HR | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.74 | .460 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −1.70 | .090 | −0.60 | 0.44 | −1.36 | .175 | −0.19 | 0.10 | −1.84 | .067 | −0.18 | 0.08 | −2.15 | .033 | |||||

| Total R2 | .100 | .098 | .050 | .080 | .076 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Note. SA = Social adversity.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.10.

Delinquency

Similarly, sex and social adversity together accounted for 4.7% of the variance of the delinquency: being male and having higher social adversity scores were associated with higher delinquency scores. When prenatal maternal stress and resting heart rate were added, the amount of variance accounted for rose to 8.8%; controlling for the child’s sex and social adversity, higher levels of prenatal stress and lower resting heart rate were each associated with higher delinquency scores. The addition of the prenatal stress × heart rate interaction term in step 3 had marginally increased the amount of variance accounted for (1%).

CU Traits

No significant effect was found for sex or social adversity. After controlling for the child’s sex and social adversity, higher prenatal stress was associated with higher CU traits. No other main effect or interaction effects involving heart rate were found significant.

Grandiose-Manipulative Traits

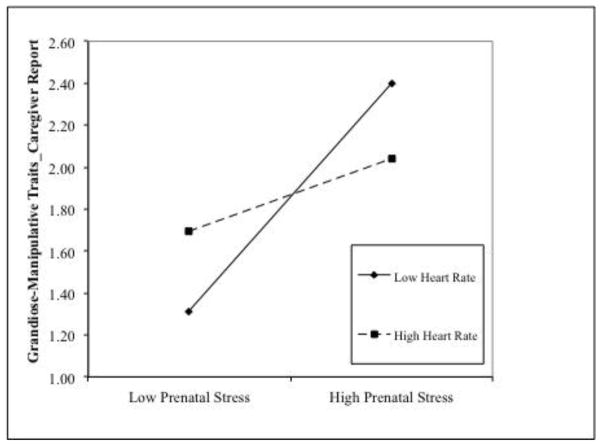

Higher levels of social adversity were associated with higher GM traits. After sex and social adversity were controlled for, prenatal stress was positively associated with GM traits. The addition of prenatal stress × heart rate had significantly increased the amount of variance accounted for (1.3%). To further probe the significant two-way interactions, these effects were broken down by examining the effects of prenatal stress on GM traits at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of heart rate (Aiken & West, 1991). Prenatal stress was positively associated with GM traits at low (β = .55, t = 2.87, p = .004) but not high levels of heart rate (β = .17, t = 1.12, p = .264, see Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

High prenatal maternal stress interacts with low heart rate in predisposing to increased scores on (caregiver-reported) grandiose-manipulative (1A) and daring-impulsive dimensions (1B). Prenatal stress was significantly associated with psychopathic traits at low levels of heart rate.

Daring-Impulsive Traits

No significant effect was observed for sex, whereas higher social adversity was associated with higher DI traits. The addition of main effects of prenatal stress and heart rate did not significantly increase the variance accounted for. However, when the prenatal stress × heart rate interaction term was added, the variance accounted for was significantly improved. Prenatal stress was positively associated with DI at low (β = .48, t = 3.04, p = .003), but not high levels of heart rate (β = .12, t = 0.91, p = .365, Figure 1B).

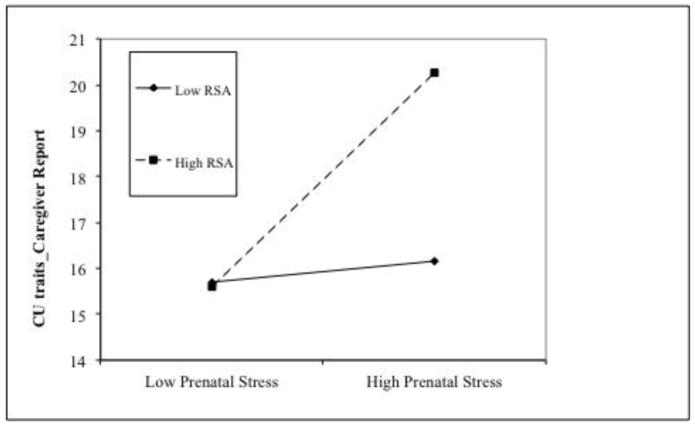

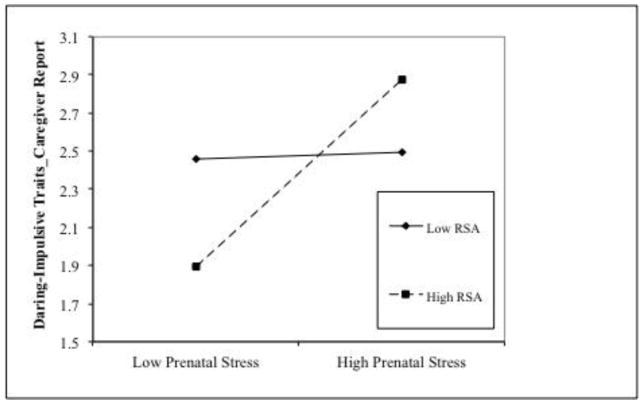

Prenatal Maternal Stress and Caregiver-Reported Behavioral Problems: the Moderating Effect of RSA

The results of the analyses are presented in Table 3. After controlling for sex and social adversity, higher RSA, but not prenatal stress was associated with higher delinquency scores. In addition, the prenatal stress × RSA interaction effect was significant when predicting CU traits and DI traits. Prenatal stress was positively associated with CU and DI at high (for CU, β = 2.37, t = 2.84, p = .005; for DI, β = 0.49, t = 3.02, p = .003), but not low levels of RSA (for CU, β = 0.23, t = 0.31, p = .759; for DI, β = 0.02, t = 0.13, p = .894, see Figure 2A and 2B). No other significant main effects or interaction effects involving RSA were found.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses between Prenatal Stress, Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia, and Caregiver Reported Behavioral Problems

| Aggression | Delinquency | CU Traits | Grandiose-Manipulative Traits |

Daring-Impulsive Traits | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | Δ R2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | .054* | .047** | .019a | .050** | .041** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.35 | 0.14 | 2.42 | .016 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 2.03 | .043 | 1.37 | 1.11 | 1.24 | .217 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.90 | .367 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 1.58 | .116 | |||||

| SA | 0.22 | 0.07 | 2.94 | .004 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 2.92 | .004 | 1.03 | 0.57 | 1.80 | .072 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 3.50 | .001 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 2.89 | .004 | |||||

| Step 2 | .037** | .044** | .026* | .020a | .015 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.37 | 0.14 | 2.60 | .010 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 2.27 | .024 | 1.47 | 1.10 | 1.34 | .181 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.94 | .350 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 1.61 | .108 | |||||

| SA | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.80 | .073 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.86 | .064 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.93 | .354 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 2.83 | .005 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 2.22 | .027 | |||||

| Prenatal Stress | 0.23 | 0.08 | 3.03 | .003 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 2.26 | .025 | 1.15 | 0.58 | 1.98 | .049 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 2.06 | .040 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 1.91 | .057 | |||||

| RSA | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.10 | .273 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2.76 | .006 | 1.01 | 0.56 | 1.81 | .072 | −0.13 | 0.13 | −0.10 | .335 | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.46 | .645 | |||||

| Step 3 | .004 | .007 | .015* | .001 | .019* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.36 | 0.14 | 2.54 | .012 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 2.21 | .028 | 1.34 | 1.09 | 1.22 | .222 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.91 | .362 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 1.48 | .141 | |||||

| SA | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.74 | .080 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.79 | .075 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.82 | .416 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 2.80 | .006 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 2.11 | .036 | |||||

| Prenatal Stress | 0.24 | 0.08 | 3.13 | .002 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 2.25 | .014 | 1.29 | 0.58 | 2.21 | .028 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 2.09 | .038 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 2.19 | .029 | |||||

| RSA | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.12 | .264 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2.81 | .005 | 1.01 | 0.56 | 1.81 | .070 | −0.13 | 0.13 | −0.96 | .338 | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.44 | .662 | |||||

| Prenatal Stress x RSA | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.01 | .313 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.41 | .160 | 1.08 | 0.53 | 2.02 | .044 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.37 | .710 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 2.25 | .025 | |||||

| Total R2 | .094 | .098 | .060 | .071 | .076 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Note. SA = Social adversity.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.10.

Figure 2.

High prenatal maternal stress interacts with high RSA in predisposing to increased (caregiver-reported) CU traits (2A) and daring-impulsive scores (2B). Prenatal stress was significantly associated with psychopathic traits at high levels of RSA.

Prenatal Maternal Stress and Child-Reported Behavioral Problems: The Moderating Effects of Heart Rate or RSA

After controlling for sex and social adversity, prenatal stress was positively associated with child-reported GM traits (β = 0.33, t = 2.13, p = .034), and marginally associated with DI traits (β = 0.25, t = 1.93, p = .055). No other significant main effects or interaction effects were found. The results of the analyses are presented in Table 4 (testing the potential moderating effects of heart rate) and Table 5 (testing the moderating effects of RSA).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses between Prenatal Stress, Heart Rate, and Child Reported Behavioral Problems

| Aggression | Delinquency | CU Traits | Grandiose-Manipulative Traits |

Daring-Impulsive Traits | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | .018a | .024a | .028* | .029* | .020a | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.00 | 0.15 | −0.02 | .987 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.87 | .062 | 2.19 | 0.88 | 2.49 | .014 | −0.05 | 0.28 | −0.18 | .858 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 1.76 | .080 | |||||

| SA | 0.17 | 0.08 | 2.17 | .031 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.68 | .095 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 1.05 | .294 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 2.70 | .007 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 1.39 | .167 | |||||

| Step 2 | .007 | .007 | .010 | .025* | .023a | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | −0.02 | 0.15 | −0.12 | .902 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 1.64 | .102 | 1.99 | 0.89 | 2.24 | .026 | −0.10 | 0.28 | −0.36 | .719 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 1.56 | .120 | |||||

| SA | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.58 | .115 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.39 | .165 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.65 | .518 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 1.61 | .110 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.44 | .664 | |||||

| Prenatal stress | 0.09 | 0.08 | 1.14 | .257 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.05 | .962 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.38 | .704 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 2.13 | .034 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 1.93 | .055 | |||||

| HR | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.92 | .360 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.33 | .184 | −0.71 | 0.46 | −1.56 | .120 | −0.24 | 0.14 | −1.64 | .102 | −0.21 | 0.12 | −1.72 | .087 | |||||

| Step 3 | .001 | .000 | .010 | .009 | .010 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | −0.02 | 0.15 | −0.12 | .906 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 1.64 | .102 | 2.00 | 0.89 | 2.25 | .025 | −0.10 | 0.28 | −0.36 | .721 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 1.57 | .118 | |||||

| SA | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.51 | .132 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.37 | .173 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.47 | .640 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 1.42 | .156 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.25 | .807 | |||||

| Prenatal stress | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.23 | .221 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.07 | .942 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.74 | .458 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 2.43 | .016 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 2.25 | .025 | |||||

| HR | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.78 | .436 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 1.27 | .204 | −0.55 | 0.47 | −1.18 | .238 | −0.19 | 0.15 | −1.28 | .200 | −0.16 | 0.12 | −1.34 | .182 | |||||

| Prenatal stress x HR | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.53 | .600 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.11 | .912 | −0.54 | 0.35 | −1.57 | .117 | −0.16 | 0.11 | −1.49 | .137 | −0.15 | 0.09 | −1.60 | .111 | |||||

| Total R2 | .100 | .031 | .047 | .063 | .053 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Note. SA = Social adversity.

p<.05,

p<.10.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses between Prenatal Stress, Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia, and Child Reported Behavioral Problems

| Aggression | Delinquency | CU Traits | Grandiose-Manipulative Traits |

Daring-Impulsive Traits | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | b | SE | t | p | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | .018 | .024* | .028* | .029* | .020a | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.00 | 0.15 | −0.02 | .987 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.87 | .062 | 2.19 | 0.88 | 2.49 | .014 | −0.05 | 0.28 | −0.18 | .858 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 1.76 | .080 | |||||

| SA | 0.17 | 0.08 | 2.17 | .031 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.68 | .095 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 1.05 | .294 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 2.70 | .007 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 1.39 | .167 | |||||

| Step 2 | .004 | .002 | .010 | .014 | .011 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.02 | .984 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 1.88 | .062 | 2.23 | 0.88 | 2.53 | .012 | −0.04 | 0.28 | −0.13 | .893 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 1.80 | .073 | |||||

| SA | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.72 | .087 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.53 | .127 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.71 | .480 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 1.87 | .062 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.76 | .447 | |||||

| Prenatal stress | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1.01 | .315 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.14 | .886 | 0.10 | 0.48 | 0.20 | .844 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 1.89 | .060 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 1.66 | .098 | |||||

| RSA | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.26 | .796 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.75 | .454 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 1.60 | .111 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.14 | .891 | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.18 | .860 | |||||

| Step 3 | .000 | .001 | .006 | .001 | .006 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.03 | .977 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 1.83 | .068 | 2.16 | 0.88 | 2.44 | .015 | −0.05 | 0.28 | −0.17 | .865 | 0.41 | 0.24 | 1.72 | .087 | |||||

| SA | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.72 | .087 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.49 | .137 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.66 | .508 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 1.85 | .066 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.71 | .476 | |||||

| Prenatal stress | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.98 | .327 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.07 | .948 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.31 | .754 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 1.94 | .054 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.77 | .078 | |||||

| RSA | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.26 | .798 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.76 | .449 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 1.61 | .109 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.14 | .887 | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.16 | .871 | |||||

| Prenatal stress x RSA | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.12 | .904 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.62 | .537 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 1.21 | .226 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.56 | .573 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 1.23 | .220 | |||||

| Total R2 | .022 | .028 | .044 | .045 | .037 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Note. SA = Social adversity.

p<.05,

p<.10.

Discussion

This study provides evidence of a significant role of the autonomic arousal in moderating the effect of early prenatal maternal stress on antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits. These results extend the findings of previous studies, which indicated that exposure to environmental adversity increased the risk of antisocial behavior among individuals with low resting heart rate (Raine et al., 2014). To our knowledge, this is the first study to show the long-term impact of prenatal maternal stress exposure on the behavioral outcomes depending on the level of autonomic arousal.

Consistent with our hypotheses, greater prenatal maternal stress was found to be associated with all antisocial outcomes reported by the caregiver in children aged 8- to 10-years old after the concurrent measure of social adversity was controlled for, suggesting that the results are less likely driven by the postnatal environment. No such effect was found for child-reported outcomes (except that prenatal stress was positively related to grandiose-manipulative scores), probably due to their relatively lower reliabilities. In addition, lower resting heart rate and higher RSA were found to correlate with higher scores on delinquency, aggression, and CU traits. These findings are also compatible with the fearlessness and underarousal theory (Raine, 1993; Raine, 2002), as aggressive and delinquent acts may be in part motivated by an individual’s lack of fear or desire to attain a higher level of arousal. Our finding that increased RSA is associated with more behavioral problems is in line with a few other studies that also used nonclinical, non-high-risk samples (Dietrich et al., 2007; Scarpa et al., 2000), but contrasts with findings of decreased vagal activity associated with externalizing problems in selected groups (see review by Beauchaine, 2012). Interestingly, we also found that higher RSA (and low heart rate) was associated with greater social adversity, supporting the proposition that vagal activity, indexing emotion regulation capability, is largely socialized within families (Beauchaine, 2012). Similarly, behavioral genetic studies have indicated that individual differences in vagal activity are in large part determined by environmental factors (Kupper, Willemsen, Posthuma, De Boer, Boomsma, & De Geus, 2005).

More intriguingly, we found a biosocial interaction effect – prenatal maternal stress was significantly associated with caregiver-reported psychopathic traits, only under the condition of low autonomic arousal. Specifically, the combination of low heart rate and high prenatal stress results in particularly high levels of grandiose-manipulative and daring-impulsive dimensions (Figure 1a and 1b), and the combination of high RSA and prenatal stress results in high CU traits and daring-impulsive scores (Figure 2a and 2b). These biosocial results fit in with a variety of other reports suggesting a higher risk of externalizing behaviors in individuals with genetic predisposition or neurobiological deficits when exposed to an adverse environment (e.g., Caspi & Moffitt, 2006; El-Sheikh et al., 2006; Raine, 2002; Raine et al., 2014; Scarpa et al., 2008). Taken together, findings illustrate the critical importance of integrating biological with social measures to fully understand how psychopathic traits develop in children, and provide further evidence that different features of psychopathic-like traits may have distinct etiologies (Salekin, 2015).

It could be argued that prenatal maternal stress and offspring’s heart rate or RSA are not independent. For example, some have reported that factors in pregnant women’s health, such as prenatal stress, are associated with fetal heart rate reactivity during a Stroop test, suggesting the possibility that fetuses of women with higher stress are more reactive to stimuli than those of women with lower stress. However, no such relationship was found between prenatal stress and fetal heart rate at resting baseline (Monk et al., 2004; Monk et al., 2011). Furthermore, to our knowledge, no study has examined the long-term effect of prenatal maternal stress on offspring’s heart rate or RSA in childhood. In the current sample, prenatal stress and arousal levels were not significantly correlated (for heart rate, r = .076; for RSA, r = .033, Table 1), indicating that these constructs reflect processes that are largely independent.

One limitation of the present research is that it is a cross-sectional study, thus we would caution that these findings do not demonstrate causal links between prenatal maternal stress/low arousal and antisocial behavior. Second, prenatal stress was assessed via standardized interviews that relied on retrospective recollection, hence possible biases may have occurred. Another limitation is that our measure of prenatal stress did not specify the period in pregnancy. Limited evidence has suggested that the effects of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol on offspring’s development are time specific. For example, one study has shown that infants exposed to higher levels of cortisol early in gestation had delayed mental development at twelve months of age, whereas those who were exposed later in gestation had better development (Davis & Sandman, 2010). Future longitudinal studies using more objective measures of maternal stress, such as cortisol levels, during specific gestation period, will help us further understand the mechanisms underlying the association between prenatal stress and offspring’s development.

Findings of the current study have important clinical implications. While a mother’s distress may affect her child at various time points, the prenatal period seems especially vulnerable. During pregnancy, distress experienced by a mother causes the release of cortisol that crosses the placenta, consequently affecting developmental outcomes that include alterations to the limbic system and prefrontal cortex (Van den Bergh, Mulder, Mennes, & Glover, 2005), brain areas imperative to social behavior. Previous work has emphasized the importance of sensitive postnatal child-rearing practices, specifically secure attachment, and demonstrated that these child-rearing practices may serve as a protective factor against the decreased cognitive ability in those exposed to higher levels of cortisol throughout gestation (Bergman et al., 2010). Since prenatal maternal stress is found to be a predictor for antisocial behaviors and psychopathic traits, in particular in those with low autonomic arousal, intervention programs focusing on targeting those born to mothers experiencing excessive levels of distress during their pregnancies may be more beneficial.

In conclusion, one advantage of the study is the use of multiple externalizing behavior outcome measures. We found that children exposed to higher prenatal maternal stress in general showed more antisocial and psychopathic behaviors in middle childhood, and this effect was unlikely driven by postnatal environment. In addition, biosocial interactions were found whereby the combination of low autonomic arousal and high prenatal stress results in highest scores on psychopathic measures. Findings suggest that reducing maternal stress during pregnancy may help to prevent, in the long run, antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits in the offspring, especially in those individuals with low autonomic arousal.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Psychophysiological Lab research staff, in particular Wei Zhang, for their assistance in collecting and processing data, and the families for participation.

Funding: This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health to the first author under Award Number SC2HD076044. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: Both authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, Vermont: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, Vermont: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, California: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barker ED, Oliver BR, Viding E, Salekin RT, Maughan B. The impact of prenatal maternal risk, fearless temperament and early parenting on adolescent callous- unemotional traits: a 14-year longitudinal investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(8):878–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(02):183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Physiological markers of emotion and behavior dysregulation in exteralizing psychopathology. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2012;77(2):79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman K, Sarkar P, Glover V, O’Connor TG. Maternal prenatal cortisol and infant cognitive development: Moderation by infant–mother attachment. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR, Leibenluft E, Pine DS. Conduct disorder and callous-unemotional traits in youth. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371:2207–2216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1315612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann AF, Zohsel K, Blomeyer D, Hohm E, Hohmann S, Jennen-Steinmetz C, … Laucht M. Interaction between prenatal stress and dopamine D4 receptor genotype in predicting aggression and cortisol levels in young adults. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231(16):3089–3097. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Davis EP, Shahbaba B, Pruessner JC, Head K, Sandman CA. Maternal cortisol over the course of pregnancy and subsequent child amygdala and hippocampus volumes and affective problems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(20):1312–1319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201295109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Gene–environment interactions in psychiatry: joining forces with neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(7):583–590. doi: 10.1038/nrn1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JRG, Sloboda D, Matthews SG, Holloway A, Alfaidy N, Patel FA, … Newnham J. The fetal placental hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, parturition and post natal health. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2001;185(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Hobel C, Chicz-Demet A, Sandman CA. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression and cortisol influences infant temperament. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):737–746. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318047b775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Sandman CA. The timing of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol and psychosocial stress is associated with human infant cognitive development. Child Development. 2010;81(1):131–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerth C, van Hees Y, Buitelaar JK. Prenatal maternal cortisol levels and infant behavior during the first 5 months. Early Human Development. 2003;74(2):139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(03)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Riese H, Sondeijker FEPL, Greaves-Lord K, van Roon A, Ormel J, … Rosmalen JG. Externalizing and internalizing problems in relation to autonomic function: A population-based study in preadolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:378–386. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31802b91ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sasagawa S, Frick PJ. Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment. 2006;13(4):454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. The relationship between low resting heart rate and violence. In: Raine A, Brenan P, Farrington D, Mednick S, editors. Biosocial bases of violence. Springer US; 1997. pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Hare RD. The Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. The Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. Unpublished rating scale 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Borlam D, Zhang W. The association between heart rate reactivity and fluid intelligence in children. Biological Psychology. 2015;107:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Raine A, Chan F, Venables PH, Mednick SA. Early maternal and paternal bonding, childhood physical abuse and adult psychopathic personality. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(06):1007–1016. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Raine A, Venables PH, Dawson ME, Mednick SA. The development of skin conductance fear conditioning in children from ages 3 to 8 years. Developmental Science. 2010;13(1):201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, van Beek J, Wientjes C. A comparison of three quantification methods for estimation of respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Psychophysiology. 1990;27(6):702–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Harvey AG, Johnson SL. Reflective and ruminative processing of positive emotional memories in bipolar disorder and healthy controls. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2009;47:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Lee SS. Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 144–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jones AP, Laurens KR, Herba CM, Barker GJ, Viding E. Amygdala hypoactivity to fearful faces in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(1):95–102. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Skeem JL, Marsee MA, Cruise K, Munoz LC, … Morris AS. Assessing callous–unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2008;31(3):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper N, Willemsen G, Posthuma D, De Boer D, Boomsma DI, De Geus EJ. A genetic analysis of ambulatory cardiorespiratory coupling. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(2):202–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: A review of the past 10 years, Part 1. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1468–1484. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mäki P, Veijola J, Räsänen P, Joukamaa M, Valonen P, Jokelainen J, Isohanni M. Criminality in the offspring of antenatally depressed mothers: A 33-year follow- up of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;74(3):273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Finger EC, Mitchell DG, Reid ME, Sims C, Kosson DS, … Blair RJR. Reduced amygdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behavior disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):712–720. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SG. Antenatal glucocorticoids and programming of the developing CNS. Pediatric Research. 2000;47(3):291–300. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Wells KC, Kotler JS. Conduct Problems. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of childhood disorders. 3. New York: Guildford Press; 2006. pp. 137–268. [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Fifer WP, Myers MM, Bagiella E, Duong JK, Chen IS, … Altincatal A. Effects of maternal breathing rate, psychiatric status, and cortisol on fetal heart rate. Developmental Psychobiology. 2011;53(3):221–233. doi: 10.1002/dev.20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Sloan RP, Myers MM, Ellman L, Werner E, Jeon J, … Fifer WP. Fetal heart rate reactivity differs by women’s psychiatric status: an early marker for developmental risk? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):283–290. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz LC, Frick PJ. The reliability, stability, and predictive utility of the self- report version of the Antisocial Process Screening Device. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2007;48(4):299–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz J, Raine A. Heart rate level and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(2):154–162. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poythress NG, Dembo R, Wareham J, Greenbaum PE. Construct validity of the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory (YPI) and the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) with justice-involved adolescents. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2006;33(1):26–55. [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kim B, Kim J, Shin M, Yoo HJ, Lee J, Cho S. Associations between maternal stress during pregnancy and offspring internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014;8(44):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. The psychopathology of crime: Criminal behavior as a clinical disorder. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. Biosocial studies of antisocial and violent behavior in children and adults: A review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(4):311–326. doi: 10.1023/a:1015754122318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Fung ALC, Portnoy J, Choy O, Spring VL. Low heart rate as a risk factor for child and adolescent proactive aggressive and impulsive psychopathic behavior. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40(4):290–299. doi: 10.1002/ab.21523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Venables PH. Tonic heart rate level, social class and antisocial behaviour in adolescents. Biological Psychology. 1984;18(2):123–132. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(84)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Venables PH, Mednick SA. Low resting heart rate at age 3 years predisposes to aggression at age 11 years: Evidence from the Mauritius Child Health Project. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(10):1457–1464. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose A, Bijttebier P, Decoene S, Claes L, Frick PJ. Assessing the affective features of psychopathy in adolescence: a further validation of the inventory of callous and unemotional traits. Assessment. 2010;17(1):44–57. doi: 10.1177/1073191109344153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT. Psychopathy in Childhood: Toward Better Informing the DSM–5 and ICD-11 Conduct Disorder Specifiers. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2015 doi: 10.1037/per0000150. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/per0000150. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sarkar S, Craig MC, Dell’Acqua F, O’Connor TG, Catani M, Deeley Q, … Murphy DG. Prenatal stress and limbic-prefrontal white matter microstructure in children aged 6–9 years: A preliminary diffusion tensor imaging study. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2014;15(4):346–352. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2014.903336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Fikretoglu D, Luscher K. Community violence exposure in a young adult sample: II. Psychophysiology and aggressive behavior. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):417–425. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Tanaka A, Chiara Haden S. Biosocial bases of reactive and proactive aggression: The roles of community violence exposure and heart rate. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36(8):969–988. [Google Scholar]

- Sterzer P, Stadler C, Kreb A, Kleinschmidt A, Poustka F. Abnormal neural responses to emotional visual stimuli in adolescents with conduct disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BR, Marcoen A. High antenatal maternal anxiety is related to ADHD symptoms, externalizing problems, and anxiety in 8-and 9-year-olds. Child Development. 2004:1085–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BR, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables PH. Biological contributions to crime causation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer; 1988. Psychophysiology and crime: Theory and data; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vitacco MJ, Rogers R, Neumann CS. The antisocial process screening device an examination of its construct and criterion-related validity. Assessment. 2003;10(2):143–150. doi: 10.1177/1073191103010002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh BC, Loeber R, Stevens BR, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Cohen MA, Farrington DP. Costs of juvenile crime in urban areas: A longitudinal perspective. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2008;6:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Zhao Y, Evans L, Kinsella M, Kurzius L, Altincatal A, … Monk C. Higher maternal prenatal cortisol and younger age predict greater infant reactivity to novelty at 4 months: An observation- based study. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55(7):707–718. doi: 10.1002/dev.21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Gao Y. Interactive effects of social adversity and respiratory sinus arrhythmia activity on reactive and proactive aggression. Psychophysiology. 2015;52(10):1343–1350. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]